Abstract

Background

Premature coronary artery disease (PCAD) seems to increase, particularly in developing countries. Given the lack of such studies in the country, this study examines the prevalence, associated cardiovascular risk factors, and coronary angiographic profile of the disease in Iraq.

Methods

Data was collected from a total of 445 adult patients undergoing coronary angiography at Duhok Heart Center, Kurdistan in a period between March and September 2014. Patients were divided into PCAD (male <45 years and female < 55 years) and mature coronary artery disease (MCAD).

Results

The prevalence of the angiographically documented PCAD was 31 %. The PCAD had higher rates of hyperlipidemia (p = 0.04), positive family history of coronary artery disease (p = 0.002), type A lesions (p = 0.02), single vessel disease (p = 0.01) and medical treatment (p = 0.01) than the MCAD. Logistic regression model indicated that male sex (OR 3.38, C.I 1.96–7.22), smoking (OR 2.08, C.I 1.05–4.12), hypertension (OR 1.58, C.I 1.25–2.03), hyperlipidemia (OR 1.89, C.I 1.17–2.42) and positive family history of coronary artery disease (OR 2.62, C.I 1.38–9.54) were associated with the PCAD. Sensitivity analysis showed highest specificity (94.2 %) and positive predictive value (96.5 %) in patients with coronary stenosis >70 % compared to lesser obstruction.

Conclusions

Premature coronary artery disease is alarming in the country. Cardiovascular risk factors are clustered among them. But the angiographic profile and therapeutic options of PCAD are close to those reported from previous studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Coronary artery disease (CAD) is a major cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide. CAD is a disease usually found in the old. Nowadays, however, it’s often encountered by young adults. It is estimated that about 4–10 % of individuals with documented CAD are less than 45 years [1, 2].

The PCAD is defined, in various studies, as having an age of onset ranging from 30 to 56 years. Clinical studies have affirmed that patients with PCAD have a different clinical presentation, associated CAD risk factors, and coronary angiographic profile compared with the MCAD [2–4].

Patients with PCAD belong to a particular subgroup that needs much more attention since its impact on individuals, families and the society is devastating. Studies on PCAD in certain countries may vary relevant to the populations studied, and the data on PCAD available in Iraq is scarce. This study was aimed at examining the prevalence, clinical presentations, associated cardiovascular risk factors, coronary angiographic profile, and therapeutic options in the PCAD compared to MCAD.

Methods

Patients’ recruitment

We examined in this cross sectional study a total of 445 clinically diagnosed CAD patients who underwent coronary angiography (CAG) at Duhok Heart Center, Kurdistan, Iraq in the period between March and September 2014. Inclusion criteria included all patients aged ≥18 years, presented with CAD/acute coronary syndrome (ACS), and underwent CAG based on the ACC/ESC indications for CAG for the first time whose coronary angiograms revealed documented coronary lesions [5, 6]. A total of 303 cases (178 men and 125 women) with a mean age 53.8 (SD 5.8) were met these criteria and provided written informed consent. From the recruited sample, 97 cases had normal angiograms and other 45 had prior coronary revascularization (PCI or CABG) and both were excluded from the study (see Fig. 1). CAD manifested in male <45 years and in female < 55 years old was defined a PCAD. Patients were divided into PCAD and MCAD group and the premature group was subdivided into males and females for comparison.

Clinical presentations and cardiovascular risk factors

Clinical presentations of patient were classified into chronic stable angina, prior acute coronary syndromes including unstable angina (UA), NSTEMI, and STEMI. Patients were checked for obesity, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, smoking, and family history of coronary artery disease. Diagnoses of these clinical presentations and cardiovascular risk factors were based on international standard definitions [7–14].

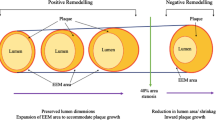

Coronary angiography

Diagnostic CAG was performed by a team of expert interventional cardiologists. A detailed analysis of angiographic images was done by the operators. Both eye-balling method and quantitative coronary angiography (QCA) were used to estimate the percentage, morphology and length of the coronary lesions. The patients were grouped according the number of major epicardial coronary arteries into one vessel disease (1VD), two vessels disease (2VD), three vessels disease (3VD) or four vessels disease including left main stem (LMS) (4VD). Stenosis of the coronary vessels was considered mild when the luminal diameter was reduced by (<50 %), moderate (50–70 %), and severe >70 % of the original diameter. Complexity of lesions was further categorized according to the joint American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) classification system into: Type A, B and C lesions [15].

Statistical analysis

Data analysis was performed by using Microsoft Office Excel 2007and SPSS for Windows, version 16.0. Chicago. Continuous variables were calculated as mean ± (SD), and categorical variables were presented as counts and percentages. A chi-square test was used to compare categorical variables. A student t- test was used for continuous variables. A logistic regression model was used to identify risk factors of premature CAD. P-value < 0.05 was regarded as significant. Sensitivity analysis was performed between different categories of coronary artery stenosis percents. The study was approved by the ethical committee at the School of Medicine, Faculty of Medical Sciences, University of Duhok, Kurdistan, Iraq.

Results

Comparison between patients with premature and Mature CAD

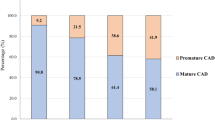

Prevalence of PCAD is (31 %). Their mean age is 44.2 (SD 5.2). Concerning male sex and STEMI as a clinical presentation, there were a statistical significant difference between the premature and mature CAD (p < 0.001, 0.029). There was a significantly higher prevalence rate of diabetes mellitus among MCAD (p = 0.002), but a significantly higher rates of hyperlipidemia and positive family history of CAD among PCAD with (p = 0.048, 0.002) respectively. Angiographically, there were higher rates of 1 VD, type A lesions and mild coronary stenosis among the PCAD. However, the rates of 3VD and 4VD, type C lesion, and moderate/severe coronary stenosis were significantly higher among the MCAD. CABG seemed to be significantly more common among patients with MCAD (p = 0.035). However, medical treatment was more advocated for PCAD (Table 1).

Comparison between males and females with PCAD

While obesity was significantly more common among females (p = 0.038), smoking was obviously more prevalent among males with PCAD (p <0.001). There was a significantly higher rate of STEMI among males (p = 0.029) as well as the rates of 3VD and 4VD were higher among them (p = 0.011 and 0.027) respectively. Therapeutic options showed no significant statistical differences between the two subgroups (Table 2).

Risk factors of PCAD

Using PCAD as a dependent variable, independent CAD risk factors among PCAD including male gender, arterial hypertension, diabetes mellitus, smoking, hyperlipidemia, and family history of CAD were assessed by logistic regression model. The analysis revealed that male gender, hypertension, smoking, hyperlipidemia, and family history of CAD were independent risk factors for PCAD (Ps < 0.05) (Table 3).

Sensitivity analysis of different categories of coronary artery stenosis showed highest specificity and positive predictive value (PPV) in patients with coronary stenosis >70 % obstruction compared to other categories of lesser obstruction (Table 4).

Discussion

This study showed an alarming higher rate of PCAD compared to most of reports and studies conducted worldwide. This rate is higher than rates reported by Mohammad et al. from Iraq, Prashanth et al. from Oman and Al-Nozha et al. from Suadia Arabia [16–18]. At the same time it is much higher than the reported rates of documented CAD in young populations in USA, India, China and Japan [19–22]. On the contrary, it is lower only than the rate reported exclusively by Zahrni et al. who found 55 % of CAD in Malaysian is of premature onset, and this is probably related to the mean age difference between both studies [23]. The age of PCAD presentation in the current study is much younger than the mean age for Zahrni et al., and is comparable to Roxona Sadeghi et al. from Iran [23, 24].

In consistence with the results found by Zahrni et al., Tahir et al., and Prashanth et al., the current study showed higher incidence of ACS compared to chronic stable angina among premature group [17, 23, 25]. But Abu Siddique et al. showed higher rates of chronic stable angina and not ACS among PCAD [26]. Interestingly among the latter group, males are more likely to present with STEMI as compared to females. This finding has also been demonstrated in other observational and retrospective analyses worldwide. This group of patients represents an area for further study and possible future interventions. Currently, there are prospective studies ongoing to evaluate subclinical markers of atherosclerosis and indeed some currently unknown risk factors may be responsible for this finding [27, 28].

This study, like Nafakhi though unlike Abu Siddique et al., revealed no significant difference in the prevalence of hypertension between premature and mature CAD [26, 29]. Noeman et al. found similar rate to the current study of hypertension among PCAD in Pakistan [30]. Compared to Prashanth et al. and Mahnoosh Foroughi et al., while this study found a lower rate of obesity among PCAD, it concluded a similar one among female gender [17, 31]. This gender difference could be attributed to many etiologies including cultural customs and social norms of the society.

The study, in accordance with Tahir et al. and Badran et al., showed a significant difference in the prevalence of diabetes mellitus between premature and mature CAD. Unlike Badran et al., however, it showed no significant gender difference of prevalence of diabetes mellitus in the PCAD [25, 32]. Besides, the study showed a significantly higher incidence of dyslipidemia in PCAD that is similar to what Penida et al. found [33].

The rate of smoking among PCAD was lower in this study compared to Roxana Sadeghi et al. (30 % vs. 46 %) [24]. Smoking was rare among females in this study likely because yet it is not popular among women in the Kurdish society. Positive family history of CAD among the premature group of this study is similar to Mahnoosh Foroughi et al. study from Iran [31]. Nevertheless, higher percentages of positive family history were found in Turkey by Yildrim et al. [34]. Though recognized as an important risk factor for ACS in PCAD, HIV significantly impacts the trend of mortality increase in such patients. Interestingly, however, our study did not show any registered cases of which HIV caused PCAD [35].

Similar to Ibrahim Shah et al. and Badran et al. studies we found a significant higher rate of mild coronary lesions among premature group though it is in contrast to S. Sadiq Shah et al., who reported no statistical difference in the severity of coronary lesions between premature and mature CAD [32, 36, 37]. This finding, in the current study, possibly related to short duration of clustering of risk factors among premature group.

Evaluating the types of coronary lesion, Tahir et al. reported no statistical difference between premature and mature CAD. This study showed a significant higher rate of type A lesions among PCAD [25]. In consistence with Badran et al., Almayali and Christus et al., the study found higher rate of single vessel disease among PCAD [32, 38, 39]. Conversely, it showed a significant higher rate of 3VD/ 4VD among mature group. Similar results were reported by many studies, including Tewari et al. [25, 32, 39, 40]. In contrast with Farhan et al., this study showed a significantly higher rate of 3VD and 4VD among males with PCAD [41].

In accordance with the Abu Siddique et al. and Nafakhi, the distribution of major epicardial coronary artery involvement in this study was independent of the age [26, 30]. The therapeutic options, including the CABG that were significantly more doable in the MCAD and medical treatments that were more common in PCAD provided that there was less complex angiographic profile among PCAD compared to MCAD, were similar to Chrustus et al. [39].

Study limitations

There are a few main limitations to this study. To start with, only patients presented with symptoms and assigned for an angiogram were diagnosed with CAD that might limit the generalizability of the results. Though the study was a single center experience that could result in a referral bias, it reflected the trends of prematurity of CAD all over the country given a close attitude, genetics and socio economic similarities among the population. No data on follow up as well as the coronary imaging (e.g. IVUS) findings of patients included were collected. Nevertheless, this study, which is the first detailed one conducted on PCAD in the country, identified an unmet scientific need in the area, enrolled a relatively large sample size to investigate the prevalence of PCAD, and clearly defined data on all patients.

Conclusions

This study concludes that the rate of premature CAD in the country is alarming and that is mostly related to the clustering of cardiovascular risk factors. To reduce rates and consequences of PCAD, it is paramount to control the cardiovascular risk factors, screen the susceptible populations at risk and improve the coronary interventional services.

Abbreviations

- ACS:

-

acute coronary disease

- CABG:

-

coronary artery bypass grafting

- CAD:

-

coronary artery disease

- CAG:

-

coronary angiography

- EF:

-

ejection fraction

- FH:

-

family history

- LAD:

-

left anterior descending artery

- LCX:

-

left circumflex artery

- MCAD:

-

mature coronary artery disease

- NPV:

-

negative predictive value

- PCAD:

-

premature coronary artery disease

- PCI:

-

percutaneous coronary intervention

- PPV:

-

positive predictive value

- QCA:

-

quantitative coronary angiography

- RCA:

-

right coronary artery

- VD:

-

vessel disease

References

Shemirani H, Separham KH. The relative impact of smoking or Hypertension on severity of premature coronary artery disease. IRCMJ. 2007;9(4):177–81.

Doughty M, Mehta R, Bruckman D, Das S, Karavite D, Tsai T, et al. Acute ischemic Heart disease: acute myocardial infarction in the young-the university of Michigan experience. Am Heart J. 2002;143(1):56–62.

Jamil G, Jamil M, AlKhazraji H, Haque A, Chedid F, Balasubramanian M, et al. Risk factor assessment of young patients with acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiovasc Dis. 2013;3(3):170–4.

Guipeng A, Zhongqi D, Xiao M, Tao G, Guishuang L, Yuguo C, et al. Risk Factors for Long-term Outcome of Drug-eluting Stenting in Adults with Early-onset Coronary Artery Disease. Int J Med Sci. 2014;11(7):721–5.

Wijns W, Kolh P, Danchin N, DiMario C, Falk V, Folliguet T, et al. Guidelines on myocardial revascularization. Eur Heart J. 2010;31(20):2501–55.

Levine GN, Bates ER, Blankenship JC, Bailey SR, Bittl JA, Bojan C, et al. ACCF/AHA/SCAI Practice Guideline:2011 ACCF/AHA/SCAI Guideline for Percutaneous Coronary Intervention:A Report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions. Circulation. 2011;124:e574–651.

O'Gara PT, Kushner FG, Ascheim DD, et al. ACCF/AHA Guideline for the Management of ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction: A Report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61(4):e78–e140.

JL Anderson, CD Adams, EM Antman, CR Bridges, RM Califf, DE Casey Jr, et al. Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Unstable Angina/Non–ST-Elevation Myocardial Infarction: A Report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50(7):e1–e157.

Fihn SD, Gardin JM, Abrams J, et al. ACCF/AHA/ACP/AATS/PCNA/SCAI/STS Guideline for the Diagnosis and Management of Patients With Stable Ischemic Heart Disease: A Report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines, and the American College of Physicians, American Association for Thoracic Surgery, Preventive Cardiovascular Nurses Association, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and Society of Thoracic Surgeons. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;60(24):e44–e164.

American Diabetes Association. Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2010. Diabetes Care. 2010;33 Suppl 1:S11–61. doi:10.2337/dc10-S011.

Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, Cushman WC, Green LA, Izzo JL, et al. The Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood PressureThe JNC 7 Report. JAMA. 2003;289(19):2560–71.

Pasternak RC. Report of the Adult Treatment Panel III: the 2001 National Cholesterol Education Program guidelines on the detection, evaluation and treatment of elevated cholesterol in adults. Cardiol Clin. 2003;21:393–8.

Parmar MS. Family history of coronary artery disease — need to focus on proper definition. Euro Heart J. 2003;24(22):2073.

Ryan H, Trosclair A, Gfroerer J. Adult Current Smoking: Differences in Definitions and Prevalence Estimates—NHIS and NSDUH, 2008. J Environ Public Health. 2012;2012:1–11.

Scanlon P, Faxon D, Audet A, et al. ACC/AHA guidelines for coronary angiography123: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Committee on Coronary Angiography) developed in collaboration with the Society for Cardiac Angiography and Interventions. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;33(6):1756–824.

Mohammad AM, Sheikho SK, Tayib JM. Relation of Cardiovascular Risk Factors with Coronary Angiographic Findings in Iraqi Patients with Ischemic Heart Disease. Am J Cardiovasc Dis Res. 2013;1(1):25–9.

Prashanth P, Kadhim S, Ibrahim A-Z, Said A. Acute Coronary Syndrome in Young Adults from Oman: Results from the Gulf Registry of Acute Coronary Events. Heart Views. 2010;11(3):93–8.

Al-Nozha MM, Arafah MR, Al-Mazrou YY, Al-Maatouq MA, Khan NB, Khalil MZ, et al. Coronary artery disease in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Med J. 2004;25(9):1165–71.

Cole JH, Sperling LS. Premature coronary artery disease: Clinical risk factors and prognosis. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2004;6(2):121–5.

Sharma M, Ganguly NK. Premature Coronary Artery Disease in Indians and its Associated Risk Factors. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2005;1(3):217–25.

Sang Z, Jin H, Tao C, Shen J, Xu Y, Liu Z. Temporal Trends in Young Chinese Patients with Acute Myocardial Infarction. Exp Clin Cardiol. 2014;20(7):1105–28.

Satoh H, Nishino T, Tomita K, Saijo Y, Kishi R, Tsutsui H. Risk factors and the incidence of coronary artery disease in young middle-aged Japanese men: results from a 10-year cohort study. Intern Med. 2006;45(5):235–9.

Muda Z, Kadir AA, Yusof Z, Yaacob LH. Premature Coronary Artery Disease among Angiographically Proven Atherosclerotic Coronary Artery Disease in North East of Peninsular Malaysia. Int J Collaborative Res Intern Med Public Health. 2013;5(7):507–16.

Sadeghi R, Adnani N, Erfanifar A, Gachkar L, Maghsoomi Z. Premature Coronary Heart Disease and Traditional Risk Factors-Can We Do Better? Int Cardiovasc Res J. 2013;7(2):46–50.

Saghir T, Qamar N, Sial J. Coronary angiographic characteristics of coronary artery disease in young adults under age of forty years compared to those over age forty. Pakistan Heart J. 2008;41(3):49–56.

Siddique A, Shrestha MP, Mohammad S, Sirajul Haque KMHS, Ahmed K, Sultan AU. Age-Related Differences of Risk Profile and Angiographic Findings in Patients with Coronary Heart Disease. BSMMU J. 2010;3(1):13–7.

D’Onofrio G, Safdar B, Lichtman JH, Strait KM, Dreyer RP, Geda M, et al. Sex differences in reperfusion in young patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: results from the VIRGO study. Circulation. 2015;14(131):1324–32.

Wegner NK. Disparities in STEMI management for the young goose and young gander: clinical, organizational, and educational challenges. Circulation. 2015;131:1310–2.

Fakhir Nafakhi HA. Coronary angiographic findings in young patients with coronary artery disease. Intern J Collaborative Res Intern Med Public Health. 2013;5(1):48–53.

Noeman A, Ahmad N, Azhar M. Coronary artery disease in young: faulty life style or heredofamilial or both. Annals. 2007;13(2):162–4.

Foroughi M, Ahranjani SA, Ebrahimian M, Saieedi M, Safi M, Abtahian Z. Coronary artery disease in Iranian young adults, similarities and differences. Open J Epidemiol. 2014;4(1):19–24.

Badran HM, Elnoamany MF, Khalil TS, Eldin MME. Age-Related Alteration of Risk Profi le, Inflamatory Response, and Angiographic Findings in Patients with Acute Coronary Syndrome. Clin Med: Cardiol. 2009;3:15–28.

Pineda J, Marín F, Roldán V, Valencia J, Marco P, Sogorb F. Premature myocardial infarction: clinical profile and angiographic findings. Int J Cardiol. 2008;126(1):127–9.

Nesligul Y, Nurcan A, Sait DM, Yeliz S, Firat O. Comparison of traditional risk factors, natural history andangiographic findings between coronary heart disease patients with age <40 and ≥40 years old. Anatolian J Cardiol. 2007;7:124–7.

Fabrizio D’A, Enrico C, Darryn A, Claudio M, Andrea C, Nayef A, et al. Prognostic Indicators for Recurrent Thrombotic Events in HIV-infected Patients with Acute Coronary Syndromes: Use of Registry Data From 12 sites in Europe, South Africa and the United States. Thromb Res. 2014;134(3):558–64.

Shah I, Faheem M, Shahzeb R, Hafizullah M. Clinical Profile, Angiographic Characteristics and Treatment Recommendations in Patients with Coronary Artery Disease. J Pak Med Stud. 2013;3(2):94–100.

Sadiq Shah S, Lubna N, Syed Habib S, Shahsawar, Shahab Ud D, Zahid Aslam A, et al. Myocardial Infarction in young versus older adults: Clinical characteristics and angiographic features. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad. 2010;22(2):187–90.

Ahmed Hussein A-M. Coronary Artery Disease in Young versus Older Adults in Hilla City: Prevalence, Clinical Characteristics and Angiographic Profile. Karbala J Med. 2012;5(1):1328–33.

Christus T, Shukkur AM, Rashdan I, Koshy T, Alanbaei M, Zubaid M, et al. Coronary Artery Disease in Patients Aged 35 or less. Heart Views J Gulf Heart Assoc. 2011;12(1):7–11.

Tewari S, Kumar S, Kapoor A, Singh U. Premature CAD in north india: an angiography study of 1971 patients. Indian Heart J. 2005;57(4):311–8.

Farhan HA. Coronary Artery Disease: Conventional Risk Factors & Angiographic Findings among Young Iraqi Adults. Univ Babylon J. 2010;2(18):644–50.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

AMM has made substantial contributions to conception and design of the study, data and statistical analysis, and writing and submitting the manuscript. HJ and SK have contributed in data acquisition and manuscript revision. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript to be published.

Authors’ information

AMM. Is an interventional cardiologist at Duhok Heart Center and Professor (Assistant) of Cardiology at Department of Medicine, Medical School, Faculty of Medical Sciences, University of Duhok, Duhok, Kurdistan, Iraq .

HJ. Cardiologist, Duhok Heart Center, Duhok, Kurdistan, Iraq

SK. Professor of Cardiology, Department of Medicine, Medical School, Faculty of Medical Sciences, University of Duhok, Kurdistan, Iraq.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Mohammad, A.M., Jehangeer, H.I. & Shaikhow, S.K. Prevalence and risk factors of premature coronary artery disease in patients undergoing coronary angiography in Kurdistan, Iraq. BMC Cardiovasc Disord 15, 155 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-015-0145-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12872-015-0145-7