Abstract

Background

In patients undergoing high-risk surgery, it is recommended to titrate fluid administration using stroke volume or a dynamic variable of fluid responsiveness (FR). However, this strategy usually requires the use of a hemodynamic monitor and/or an arterial catheter. Recently, it has been shown that variations of central venous pressure (ΔCVP) during an alveolar recruitment maneuver (ARM) can predict FR and that there is a correlation between CVP and peripheral venous pressure (PVP). This prospective study tested the hypothesis that variations of PVP (ΔPVP) induced by an ARM could predict FR.

Methods

We studied 60 consecutive patients scheduled for high-risk abdominal surgery, excluding those with preoperative cardiac arrhythmias or right ventricular dysfunction. All patients had a peripheral venous catheter, a central venous catheter and a radial arterial catheter linked to a pulse contour monitoring device. PVP was always measured via an 18-gauge catheter inserted at the antecubital fossa. Then an ARM consisting of a standardized gas insufflation to reach a plateau of 30 cmH2O for 30 s was performed before skin incision. Invasive mean arterial pressure (MAP), pulse pressure, heart rate, CVP, PVP, pulse pressure variation (PPV), and stroke volume index (SVI) were recorded before ARM (T1), at the end of ARM (T2), before volume expansion (T3), and one minute after volume expansion (T4). Receiver-operating curves (ROC) analysis with the corresponding grey zone approach were performed to assess the ability of ∆PVP (index test) to predict FR, defined as an ≥ 10% increase in SVI following the administration of a 4 ml/kg balanced crystalloid solution over 5 min.

Results

∆PVP during ARM predicted FR with an area under the ROC curve of 0.76 (95%CI, 0.63 to 0.86). The optimal threshold determined by the Youden Index was a ∆PVP value of 5 mmHg (95%CI, 4 to 6) with a sensitivity of 66% (95%CI, 47 to 81) and a specificity of 82% (95%CI, 63 to 94). The AUC’s for predicting FR were not different between ΔPVP, ΔCVP, and PPV.

Conclusion

During high-risk abdominal surgery, ∆PVP induced by an ARM can moderately predict FR. Nevertheless, other hemodynamic variables did not perform better.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

When caring for patients undergoing high-risk surgery, the judicious titration of fluid administration in order to avoid both hypo- and hypervolemia (and the resulting perioperative complications) is considered standard of care [1]. This is best achieved through well-informed and frequent assessments of each patient’s fluid responsiveness (FR) [2]. Static hemodynamic indicators such as mean arterial pressure (MAP) and central venous pressure (CVP) have been poorer indicators of FR than dynamic variables like pulse pressure variation (PPV) or stroke volume variation (SVV) [3]. Like PPV, CVP variations throughout the mechanical respiratory cycle have been shown to predict FR [4, 5]. More recently, variations of CVP during an alveolar recruitment maneuver (ARM) have also shown promise in predicting FR [6]. Clearly, the insertions of a central venous catheter is not always desirable for every type of patient’s perioperative management. In this context, peripheral venous pressure (PVP) has demonstrated a consistent and high degree of agreement with CVP in the perioperative period in patients without significant cardiac dysfunction [7, 8]. As a peripheral venous catheter is present in the vast majority of surgical patients, PVP measurement only requires an additional pressure sensor. Additionally, PVP have proven useful in determining FR in critically ill patients [9] and may be an indicator of preload responsiveness during volume resuscitation from hemorrhage [10].

The primary objective of this study was to test the hypothesis that dynamic variations of PVP (∆PVP) during an ARM can predict FR in mechanically ventilated patients undergoing high-risk abdominal surgery. Secondary objectives were (1) to compare FR predictability between ΔPVP and other hemodynamic variables (SVI, PPV, ΔPVC) and (2) to analyze the relationship between CVP and PVP by a linear regression and a Bland-Altman analysis.

Methods

We applied the 2015 STARD guidelines for performing and reporting the results of this study [11], which took place at Paul Brousse Hospital between January 2022 and April 2022. The study protocol was approved on 17/06/2021 by the ethics committee of St Etienne (IRBN902021/CHUSTE) and registered on clinical trials (NCT05131516) on 23/11/2021 prior to the first patient inclusion. Informed consent was obtained before surgery in all patients.

Inclusion criteria were adult patients (≥ 18 years old) scheduled for a high-risk abdominal surgery and equipped with a radial arterial catheter connected to a cardiac output hemodynamic monitoring device (standard practice in our institution). Non-inclusion criteria were the presence of cardiac arrhythmias or known right ventricular dysfunction.

Anesthesia protocol

Anesthesia management was standardized in all patients during the study period. Upon arrival in the operating room, patients were moved onto a heated mattress. The following noninvasive monitors were attached: 5-lead electrocardiogram, noninvasive blood pressure, rectal temperature probe, frontal lobe electroencephalogram (with a target Bispectral index of 40 to 60), and depth of neuromuscular block monitoring. A Foley catheter was introduced. Vascular access consisted of two large-diameter peripheral venous catheters (one 16-gauge for drug administration and another 18-gauge inserted at the antecubital fossa and connected to the patient monitor via a pressure catheter). Care was taken to ensure that the patient’s arm with the peripheral intravenous catheter was unobstructed by draping, tucking, or positioning. A radial arterial catheter was also inserted after anesthesia induction and connected via the Flotrac sensor to an uncalibrated pulse contour analysis monitoring device (EV1000, Edwards Lifesciences, Irvine, USA). Then a 16 cm, 8.5 F triple-lumen central venous catheter (Arrow International Inc, Division of Teleflex Medical Inc, Everett, MA, USA) was placed under ultrasound guidance into the right jugular vein. All pressure transducers (Medex Medical Ltd, Rossendale, Lancashire, UK) were placed at the level of the mid-axillary line. General anesthesia was induced with sufentanil and propofol with neuromuscular blockade being initially achieved using succinylcholine (if potassium was in the normal range) and maintained intraoperatively with atracurium. Maintenance of anesthesia was achieved using a sufentanil infusion and inhaled sevoflurane. All patients received mechanical ventilation using a volume control mode with tidal volumes of 7 to 8 ml/kg of predicted body weight, a positive end expiratory pressure (PEEP) of 5 cm H20, and a respiratory rate adjusted to achieve an end tidal carbon dioxide between 35 and 40 cm H2O. Baseline fluid administration consisted of a balanced crystalloid infusion (Ringer’s lactate) at a rate of 1 ml/kg/h and fluid challenges of 4 ml/kg to optimize SVI during surgery.

Alveolar recruitment maneuver and data collection

An ARM was performed before skin incision, using an insufflation pressure of 30 cmH2O for 30 s [12]. Invasive systolic arterial pressure (SAP), diastolic arterial pressure (DAP), systemic pulse pressure (SAP-DAP), MAP, heart rate (HR), CVP, PVP, PPV and SVI were recorded before the ARM (T1), at the end of the ARM (T2), before volume expansion (T3), and 1 min after a volume expansion of 4 mL/kg of balanced crystalloid solution (Ringer’s lactate) administered over 5 min (T4) (Fig. 1) [13]. After the ARM, ventilatory settings were set back to initial settings. The ARM was stopped if severe arterial hypotension (systolic arterial pressure less than 70 mmHg) or severe hypoxemia (SpO2 < 80%) developed [14]. Patients were classified as fluid responders if SVI increased by ≥ 10% following the volume expansion [15].

A video of the hemodynamic monitors was recorded during the study protocol, with the clinician announcing at each time points the different values. Hemodynamic values were later documented by pausing on the video during the two last seconds of each time plot.

Statistics

All hemodynamic variables are presented as either mean (SD) or median (25th.

to 75th percentiles), depending on the normality of distribution of data (Kolmogorov–Smirnov test). Subjects were allocated according to the percentage change in SVI induced by volume expansion. Volume responders were defined by an increase of SVI ≥ 10% following the volume expansion.

We calculated the absolute values of the variations (∆) of the hemodynamic parameters between the value at the plateau pressure of 30 cmH20 (T2) and the value at the respiratory baseline (T1) for the following variables: ∆PVP, ∆CVP, ∆MAP, pulse pressure [(SAP-DAP); ∆PP]. We also recorded the respiratory variations of the arterial pulse pressure induced by mechanical ventilation [pulse pressure variation (PPV)] at T1, T3, and T4.

In order to verify the reliability of SV throughout the study protocol, the correlation between SV measurements at the two baseline steps (T1 before ARM and T3 before volume expansion) was compared using a random-effects model to ensure that large changes did not occur [16].

Differences between T1 and T2, and between T3 and T4 were assessed by a Wilcoxon test or a paired sample t-test according to the distribution of the differences. Responder and non-responder group data were compared using a Mann-Whitney test. The relationship between PVP and CVP was determined by a linear regression analysis plotting all the paired data using the coefficient of determination R² and by a Bland-Altman analysis with multiple observations per individual. To assess the ability of measured/calculated parameters to identify responders of intravascular fluid administration, receiver-operating characteristic (ROC) curves were generated, varying the discriminating threshold for ∆SVI, ∆CVP, ∆PVP, ∆MAP, ∆PP, and PPV. The optimal threshold value using the Youden index (the value that maximizes the sum of the sensitivity and specificity) was also determined. The areas under the ROC curves were calculated for each variable and compared as described previously [17]. We defined the grey zone for which strict conclusions could not be obtained as threshold values with a sensitivity lower than 90% or specificity lower than 90% [18].

A sample size of 55 patients was calculated to be sufficient to demonstrate that PVP variations could predict fluid responsiveness with an area under curve (AUC) above 0.75 [19], a ratio of non FR /FR groups of 1;1, with a power of 99% (beta risk = 0.01), an alpha risk of 0.01, and a null hypothesis value of 0.5. Considering a drop off around 10%, we decided to include 60 patients. Statistical analysis and sample size calculation were performed using MedCalc® Statistical Software version 19.6.4 (MedCalc Software Ltd, Ostend, Belgium).

Results

Sixty patients were included in the statistical analysis. No patients were excluded, and no patient was given any vasopressor medication. No patients experienced hemodynamic instability during the ARM requiring a cessation of the maneuver. Table 1 describes patient’s characteristics. Among the study collective, 32 patients (53%) were fluid responders and 28 (47%) were not. ICC for SVI between T1 and T3 was 0.98 (95% CI 0.97–0.99).

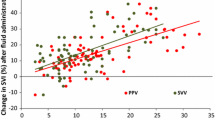

Hemodynamic variables at the study baseline, during the ARM, before the fluid challenge and after the fluid challenge between responders and non-responders are shown in Table 2. ∆PVP during an ARM predicts FR with an area under the ROC curves of 0.76 (95% CI, 0.63 to 0.86). The optimal threshold was a ∆PVP value of 5 mmHg (95% CI, 4 to 6) with a sensitivity of 66% (95% CI, 47 to 81) and a specificity of 82% (95% CI, 63 to 94) (Fig. 2). Proportions of values lying in the grey zone (value presenting a sensitivity lower than 90% or a specificity lower than 90%) ranged from 43 to 67% according to the tested variable (Table 2). The AUC’s for predicting FR were not different between ΔPVP and other hemodynamic variables such as ΔCVP and PPV (Table 2; Supplemental Fig. 1).

Receiver operating curves generated for changes in stroke volume index (SVI) induced by alveolar recruitment maneuver (ARM), changes in peripheral venous pressure induced by ARM, showing the ability to predict the effect of a volume expansion. Notes: alveolar recruitment maneuver consisted of applying a continuous positive airway pressure of 30 cm H2O for 30 s. The grey zone shows is delimited by two cut off values corresponding to a sensitivity of 90% (upper right corner) and a specificity of 90% (lower left corner). Values lying in the grey zone express a degree of uncertainty wherein the physician should pursue a diagnosis using additional tools. Legend: AUC: Area Under the Curve

PVP before the ARM in fluid responder patients was significantly lower than in non-responder patients (p = 0.0125). PVP increased significantly whatever the categorization of the patient (responder or not responder). Figure 3 depicts the evolution of PVP in responders and non-responders during the 4 time points. Table 3 shows the diagnostic performance of all hemodynamic variables to predict fluid responsiveness during the ARM.

The regression equation between PVP and CVP was significant (p < 0.0001; y = 4.44 + 0.71*x), with a coefficient of determination (R²) of 0.37 (supplemental Fig. 2). The Bland-Altman analysis with the limits of agreement and their 95% CI is presented Fig. 4.

Discussion

The present study demonstrates that variation of the PVP induced by an ARM moderately predicted FR in mechanically ventilated patients in the operating room. It was not inferior to other commonly studied variables, including ΔCVP or PPV. To our knowledge, this is the first time that the variation of PVP induced by an ARM has been studied in surgical patients. However, despite a ROC curve value > 0.75 [19], and a relatively large number of patients compared to recent studies [13, 20, 21], a significant proportion of patient’s ∆PVP values were in the inconclusive grey zone. Indeed, ΔPVP may be useful only in 38% of the patients to assess fluid responsiveness. This highlights the difficulty and limitations of only using one hemodynamic variable to predict FR. A multimodal approach by combining other hemodynamic variables may limit the clinical uncertainty of FR.

Peripheral venous pressure is easy to measure and could be considered noninvasive as all surgical patients have at least one peripheral venous catheter. In this context, most patients may benefit from this easy and non-expensive monitoring wherein the insertion of an invasive arterial catheter or a CVP may not be necessary. Moreover, monitoring PVP during an ARM may be helpful when contraindications for the use of invasive PPV are present, such as atrial fibrillation, tidal volume < 8 mL/kg of ideal body weight, or a heart rate/respiratory rate ratio lower than 3.6 [22], especially as the percentage of patients without any contraindications has been documented between only 9% and 39% [23]. However, the potential added value of PPV to predict FR should be validated in future studies, including patients with a contraindication to the use of PPV.

PVP has been previously studied in a porcine model where it predicted FR during hypovolemic shock [10]. In cardiac surgery patients, Marques et al. found that PVP could not reliably predict FR, with an area under the ROC curve of 0.72 with large limits of agreement (95% confidence interval 0.52–0.92; p = 0.058) [24]. Importantly, the lack of dynamic tool to induce the PVP variation and the reduced left ventricular compliance may explain these results.

Our results showed a mild to moderate relationship between PVP and CVP (R²=0.37) with a Bland-Altman analysis showing large limits of agreement (+ 5.7/-9.1 mmHg). A Study observed an improved PVP to CVP correlation with increasing CVP values [25], another observed or a decrease of the PVP-CVP gradient after fluid loading [10] or during the ARM. Importantly, we measured PVP at the antecubital fossa and, as a result, did not measure the mean systemic filling pressure (msfP), which is the theoretical component of the driving pressure of the venous return (msfP-CVP) generated by the right heart [26]. PVP values may have been flawed by two conditions linked to the observational approach of this study. First, a collapse of the vein due to the absence of peripheral venous flow during low venous pressure states may have resulted in artificially low PVP values. Interestingly, the addition of a slow continuous flow of isotonic saline may prevent this collapsibility. Second, the contact between the venous catheter and endothelial wall may have resulted in artificially high PVP values. Performing an echographic assessment of the vein diameter and location of the distal position of the catheter may help decrease this inaccuracy. These two environmental constraints may partially explain the outliers of the Bland-Altman graph.”

The study has known limitations. First, the sample size calculation could have been further optimized by choosing a higher null hypothesis ROC curve value. We ultimately decided to use 0.5 as the null hypothesis AUC ROC curve value in order to avoid establishing an insurmountably large sample size requirement, at the known cost of a weakened statistical outcome. Secondly, our protocol was conducted prior to surgical incision, where hemodynamics are not affected by significant surgical-induced changes in sympathetic tone. However, the vasoplegia induced by the anesthesia induction may have affected pulse pressure by decreasing the DAP. Further studies are needed to explore if ΔPVP can predict FR during the intraoperative period, wherein fluid expansion is typically more complex. It is important to note that a fluid challenge is recommended before incision to optimize fluid status when stroke volume is measured [27]. Additionally, the initial apneic period following induction may have resulted in increased alveolar collapse and a potential exaggerated response to the ARM when compared to an intraoperative challenge. We also did not analyze the potential impact of the ARM on the venous waveform during abdominal insufflation or during different peak airway pressures [8]. Our study was oriented towards bedside applicability and the precise analysis of the venous waveform can be quite challenging in real time. Finally, our ARM lasted 30 s, wherein FloTrac values average hemodynamic values every 20 s. We therefore cannot accurately interpret ΔSVI during ARM during such a short period.

Conclusion

In patients undergoing high-risk abdominal surgery, ∆PVP induced by an ARM can moderately predict FR with a high grey zone inclusion. Interestingly, other hemodynamic variables did not better predict FR. As the PVP values do not rely on additional expensive devices, the clinician may benefit from this additional hemodynamic variable to better optimize the patient’s fluid status. In the current era of enhanced recovery within the context of reducing health care costs, additional non-invasive and low-cost approaches may be warranted. However, further outcome studies based on these data should be performed to confirm its potential role in perioperative hemodynamic management.

Data availability

The database is closed and there is no public access. However, permission to access and use the database can be obtained if necessary by request to the corresponding author.

Abbreviations

- ARM:

-

Alveolar recruitment maneuver

- AUC:

-

Area under the curve

- CVP:

-

Central venous pressure

- DAP:

-

Diastolic Arterial Pressure

- FR:

-

Fluid Responsiveness

- MAP:

-

Mean Arterial PressurePVP:Peripheral venous pressure

- PPV:

-

Pulse Pressure Variation

- ROC:

-

receiver operating characteristics

- SAP:

-

Systolic Arterial Pressure

- SVV:

-

Stroke Volume Variation

- SVI:

-

Stroke Volume Index

References

Fellahi J-L, Futier E, Vaisse C, Collange O, Huet O, Loriau J, et al. Perioperative hemodynamic optimization: from guidelines to implementation-an experts’ opinion paper. Ann Intensive Care. 2021;11:58. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13613-021-00845-1.

Navarro LHC, Bloomstone JA, Auler JOC, Cannesson M, Rocca GD, Gan TJ, et al. Perioperative fluid therapy: a statement from the international fluid optimization Group. Perioper Med (Lond). 2015;4:3. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13741-015-0014-z.

Marik PE, Cavallazzi R. Does the central venous pressure predict fluid responsiveness? An updated meta-analysis and a plea for some common sense. Crit Care Med. 2013;41:1774–81. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0b013e31828a25fd.

Cherpanath TGV, Geerts BF, Maas JJ, de Wilde RBP, Groeneveld AB, Jansen JR. Ventilator-induced central venous pressure variation can predict fluid responsiveness in post-operative cardiac surgery patients. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2016;60:1395–403. https://doi.org/10.1111/aas.12811.

Westphal GA, Silva E, Caldeira Filho M, Roman Gonçalves AR, Poli-de-Figueiredo LF. Variation in amplitude of central venous pressure curve induced by respiration is a useful tool to reveal fluid responsiveness in postcardiac surgery patients. Shock. 2006;26:140–5. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.shk.0000227439.76418.7d.

Vallier S, Bouchet J-B, Desebbe O, Francou C, Raphael D, Tardy B, et al. Slope analysis for the prediction of fluid responsiveness by a stepwise PEEP elevation recruitment maneuver in mechanically ventilated patients. BMC Anesthesiol. 2022;22:4. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12871-021-01544-x.

Tugrul M, Camci E, Pembeci K, Al-Darsani A, Telci L. Relationship between peripheral and central venous pressures in different patient positions, catheter sizes, and insertion sites. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2004;18:446–50. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.jvca.2004.05.022.

Wardhan R, Shelley K. Peripheral venous pressure waveform. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2009;22:814–21. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACO.0b013e328332a343.

Charalambous C, Barker TA, Zipitis CS, Siddique I, Swindell R, Jackson R, et al. Comparison of peripheral and central venous pressures in critically ill patients. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2003;31:34–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/0310057X0303100106.

Kinsky M, Ribeiro N, Cannesson M, Deyo D, Kramer G, Salter M, et al. Peripheral venous pressure as an Indicator of Preload Responsiveness during volume resuscitation from Hemorrhage. Anesth Analg. 2016;123:114–22. https://doi.org/10.1213/ANE.0000000000001297.

Bossuyt PM, Reitsma JB, Bruns DE, Gatsonis CA, Glasziou PP, Irwig L, et al. STARD 2015: an updated list of essential items for reporting diagnostic accuracy studies. BMJ. 2015;351:h5527. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.h5527.

Hartland BL, Newell TJ, Damico N. Alveolar recruitment maneuvers under General Anesthesia: a systematic review of the literature. Respir Care. 2015;60:609–20. https://doi.org/10.4187/respcare.03488.

Aya HD, Ster IC, Fletcher N, Grounds RM, Rhodes A, Cecconi M. Pharmacodynamic analysis of a Fluid Challenge. Crit Care Med. 2016;44:880–91. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0000000000001517.

Santos RS, Silva PL, Pelosi P, Rocco PR. Recruitment maneuvers in acute respiratory distress syndrome: the safe way is the best way. World J Crit Care Med. 2015;4:278–86. https://doi.org/10.5492/wjccm.v4.i4.278.

Guinot P-G, Urbina B, de Broca B, Bernard E, Dupont H, Lorne E. Predictability of the respiratory variation of stroke volume varies according to the definition of fluid responsiveness. Br J Anaesth. 2014;112:580–1. https://doi.org/10.1093/bja/aeu031.

Shrout PE, Fleiss JL. Intraclass correlations: uses in assessing rater reliability. Psychol Bull. 1979;86:420–8. https://doi.org/10.1037//0033-2909.86.2.420.

DeLong ER, DeLong DM, Clarke-Pearson DL. Comparing the areas under two or more correlated receiver operating characteristic curves: a nonparametric approach. Biometrics. 1988;44:837–45.

Cannesson M, Le Manach Y, Hofer CK, Goarin JP, Lehot J-J, Vallet B, et al. Assessing the diagnostic accuracy of pulse pressure variations for the prediction of fluid responsiveness: a “gray zone” approach. Anesthesiology. 2011;115:231–41. https://doi.org/10.1097/ALN.0b013e318225b80a.

Ray P, Manach YL, Riou B, Houle TT, Warner DS. Statistical evaluation of a Biomarker. Anesthesiology. 2010;112:1023–40. https://doi.org/10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181d47604.

Biais M, Lanchon R, Sesay M, Le Gall L, Pereira B, Futier E, et al. Changes in stroke volume Induced by Lung Recruitment Maneuver Predict Fluid responsiveness in mechanically ventilated patients in the operating room. Anesthesiology. 2017;126:260–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/ALN.0000000000001459.

Watanabe R, Suehiro K, Mukai A, Tanaka K, Yamada T, Mori T, et al. Changes in stroke volume induced by lung recruitment maneuver can predict fluid responsiveness during intraoperative lung-protective ventilation in prone position. BMC Anesthesiol. 2021;21:303. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12871-021-01527-y.

Teboul J-L, Monnet X, Chemla D, Michard F. Arterial pulse pressure variation with mechanical ventilation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;199:22–31. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201801-0088CI.

Maguire S, Rinehart J, Vakharia S, Cannesson M. Technical communication: respiratory variation in pulse pressure and plethysmographic waveforms: intraoperative applicability in a north american academic center. Anesth Analg. 2011;112:94–6. https://doi.org/10.1213/ANE.0b013e318200366b.

Marques NR, De Riese J, Yelverton BC, McQuitty C, Jupiter D, Willmann K, et al. Diastolic function and peripheral venous pressure as indices for Fluid responsiveness in Cardiac Surgical Patients. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2019;33:2208–15. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.jvca.2019.01.007.

Cave G, Harvey M. The difference between peripheral venous pressure and central venous pressure (CVP) decreases with increasing CVP. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2008;25:1037–40. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0265021508004742.

Berger D, Takala J. Determinants of systemic venous return and the impact of positive pressure ventilation. Ann Transl Med. 2018;6:350. https://doi.org/10.21037/atm.2018.05.27.

Vallet B, Blanloeil Y, Cholley B, Orliaguet G, Pierre S, Tavernier B, et al. Guidelines for perioperative haemodynamic optimization. Ann Fr Anesth Reanim. 2013;32:e151–158. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annfar.2013.09.010.

Acknowledgements

All the clinicians who helped in data collection from the current abdominal surgery database.

Funding

The authors received no funding for this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors read and approved the final manuscript. O.D: Analyzed the data (statistical analysis) and drafted the manuscript. S.V: Analyzed the data and critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content and edited the final manuscript. L.G: Collected and analyzed the data and edited the final manuscript. B.A: Collected and analyzed the data and edited the final manuscript. A.M: Collected and analyzed the data and edited the final manuscript. E.BJ: Collected and analyzed the data and edited the final manuscript. H.K: Collected and analyzed the data and edited the final manuscript. L.T: Collected and analyzed the data and edited the final manuscript. A.B: Collected and analyzed the data and edited the final manuscript. J.D: analyzed the data and critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content and edited the final manuscript. JLV: analyzed the data and critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content and edited the final manuscript. A.J: Designed the study, collected and analyzed the data and drafted the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent for publication

The study protocol was approved by the ethics committee (IRBN902021/CHUSTE) of St Etienne on June 17th, 2021 and registered on clinical trials (NCT05131516) on 23/11/2021 prior to the first patient inclusion. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. This study adheres to the STROBE guidelines. Informed consent was obtained before surgery in all patients.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

AJ is a consultant for Edwards Lifesciences (Irvine, California, USA), Aguettant Laboratoire (Lyon, France) and Fresenius Kabi (Bad Homburg, Germany). OD is consultant for Medtronic (Trévoux, FRANCE) and received honoraria for giving lectures for Medtronic (Trévoux, FRANCE) and Livanova (Châtillon, France). The other authors have no conflicts of interest related to this article.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Desebbe, O., Vallier, S., Gergelé, L. et al. Diagnostic accuracy of the peripheral venous pressure variation induced by an alveolar recruitment maneuver to predict fluid responsiveness during high-risk abdominal surgery. BMC Anesthesiol 23, 249 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12871-023-02194-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12871-023-02194-x