Abstract

Background

Both wound infiltration (WI) with local anaesthetic and Erector Spinae Plane block (ESPB) have been described for post-operative analgesia after abdominal surgery. This study compared the efficacy of WI versus ESPB for post-operative analgesia after laparoscopic assisted colonic surgery.

Methods

Seventy-two patients between 18 and 85 years of age undergoing elective surgery were randomised to receive either WI or ESPB. In the WI group a 40 ml bolus of 0.5% Ropivacaine, infiltrated at the ports and minimally invasive wound at subcutaneous and fascia layers. In the ESPB group at T8 level, under ultrasound guidance, a 22-gauge nerve block needle was passed through the Erector Spinae muscle to reach its fascia. A dose up to 40 ml of 0.5% Ropivacaine, divided into two equal volumes, was injected at each side. Both groups had a multimodal analgesic regime, including regular Paracetamol, dexamethasone and patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) with Fentanyl. The primary end point was a post-operative pain score utilising a verbal Numerical Rating Score (NRS, 0–10) on rest and coughing in the post anaesthetic care unit (PACU) and in the first 24 h. Secondary outcomes measured were: opioid usage, length of stay and any clinical adverse events.

Results

There was no significant treatment difference in PACU NRS at rest and coughing (p-values 0. 382 and 0.595respectively). Similarly, there were no significant differences in first 24 h NRS at rest and coughing (p-values 0.285 and 0.431 respectively). There was no significant difference in Fentanyl use in PACU or in the first 24 h (p- values 0.900 and 0.783 respectively). Neither was there a significant difference found in mean total Fentanyl use between ESPB and WI groups (p-value 0.787).

Conclusion

Our observations found both interventions had an overall similar efficacy.

Trial registration

The study was registered with the Australian New Zealand Clinical Trial Registry (ACTRN: 12619000113156).

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The Erector Spinae Plane block (ESPB) was first described by Forero, in 2016 [1]. Initially, the block was performed for thoracic and breast surgery and its use has now been reported for abdominal surgery [2,3,4]. This block has gained popularity in the last 5 years, as one of the options for post-operative pain relief after abdominal surgery [2,3,4]. Both single bolus injection and catheter technique have proven to be beneficial as part of multimodal analgesia in surgeries involving the thorax and abdomen [5,6,7,8]. The technique involves injecting local anaesthetic (LA) into the myofascial plane beneath the fascia covering the Erector Spinae muscle using real time ultrasound guidance. This approach is gaining popularity mainly due to its simplicity in performance. It is relatively easy to visualise the para spinal muscles at the mid thoracic about 3 cm lateral to the midline. Clinical trials reported to be effective in use of ESPB in laparoscopic cholecystectomy [9,10,11] but not in laparoscopic colonic surgery.

The purpose of this study was to assess the efficacy of single injection ESPB performed for post-operative analgesia in laparoscopic assisted colonic surgery. Efficiency was assessed by comparing pain scores. We hypothesized that ultrasound guided ESPB is superior to wound infiltration performed at the end of surgery in providing pain relief without major side effects.

Methods

The study was conducted at The Queen Elizabeth Hospital (TQEH), part of Central Adelaide Local Health Network (CALHN) between January 2019 and September 2020. The study was registered with the Australian and New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (ACTRN12619000113156 date 24/01/2019). Institutional Human Ethics and Research Committee (HREC/18/CALHN/456) approval was obtained and all patients provided prior informed consent for their participation in the study.

The primary end point was post-operative pain score utilising a verbal Numerical Rating Score (NRS, 0–10) on rest and coughing in PACU and during the first 24 h (worst NRS on rest and coughing). Secondary outcomes measured were opioid usage until 24 h post-operatively, length of stay (days) and clinical determinants of adverse effects.

Patients with an American Society of Anesthesiologists Physical Status 1–3, greater than 18 years of age, and undergoing elective laparoscopic colonic surgery, were recruited for the study to receive either ESPB or WI at the end of surgery and before extubation. Patients were excluded if they had communication barriers, sensitivity or allergy to local anaesthetics, were pregnant, had a pre-operative daily use of opioids equivalent to 10 mg/day of morphine or above or if the procedure could not be performed laparoscopically. The study was designed with the groups randomised to the intervention allocation based on a computer-generated sequence.

All patients received a standardized general anaesthetic technique and monitoring. They were administered intermittent intravenous fentanyl as intra-operative opioid analgesia. At the end of procedure, before extubation, an ESPB was performed by an experienced anaesthetist or the WI was performed by the surgical fellow/consultant.

An in-plane approach in the lateral position was used under ultrasound guidance for the ESPB. T8 level was confirmed by counting the spinous process from T1 down to T8. Using a 6- to 15-MHz high-frequency linear probe (Sonosite X-Porte, SonoSite Inc. Bothell, WA, USA), the 2 muscle layers of the posterior spine anatomy, namely trapezius and erector spinae (ES) muscles, were visualized slightly cephalad to the T8 transverse process. The 22-gauge stimuplex (Pajunk, Geisingen, Germany) nerve block needle tip was placed deep to the ES muscle, beneath the fascia in a cephalad to caudal direction. Needle position was confirmed by a 3 ml normal saline test dose under ultrasound guidance to observe linear spread lifting the ES muscle. Ropivacaine (AstraZeneca Pty Ltd., Sydney, NSW, Australia) dissemination was confirmed lifting the ES muscle in real time under ultrasound guidance from start to completion of injection. A dose of 40 ml of 0.5% Ropivacaine (200 mg), divided into two equal volumes, was injected at each side. In the WI group 40 ml of 0.5% Ropivacaine was injected at the surgical ports and into the minimally invasive wound. In the PACU and subsequently in the wards for 24 h (time from PACU), patients were observed and questioned for signs and symptoms of local anaesthetic systemic toxicity (LAST), such as perioral numbness, tingling sensation, tinnitus, metallic taste, muscle twitching, and convulsions. Sensory block was assessed by recovery staff after surgery in PACU using a cold test on either side of the anterior abdomen between xiphi-sternum and pubic symphysis (dermatomes T6-L1).

All patients had a pre-operative ECG and a repeat ECG was to be performed if any signs and symptoms of LA toxicity were observed. Patients were administered Paracetamol 1 g QID (orally or IV) and received a single dose of Dexamethasone 8 mg intra-operatively as part of a multimodal analgesic approach. A Fentanyl PCA device (bolus 10 to 40 mcg based on age; lockout time 5 min; no background infusion) was provided as rescue analgesia. The difference in PCA usage was used as an indication of efficacy of the analgesic techniques. The primary endpoints measured were NRS for Pain at rest and on coughing in PACU at 0 and I hour and in the post-operative ward at 24 h. Other end points were Fentanyl use in PACU and first 24 h, any rescue medication used, procedure related technical issues, potential side effects or complications in relation to the technique used and length of stay (days). Data was entered in excel by the research assistant at the trial centre, who has blinded the statistician for group allocation.

Statistical analysis

Continuous measures are presented as means with standard deviations and medians with interquartile ranges, based on the normality of their distribution. Categorical measures are presented as frequencies and percentages. Group comparisons on baseline characteristics were assessed using Student’s T-test, a Wilcoxon Rank Sum test, Pearson’s Chi-square statistic or Fisher’s Exact Test as required, and linear mixed-effects models were used to compare pain and fentanyl use between ESP and WI groups, across time periods, adjusting for repeated measurements over time. Linear regressions were also used for two fentanyl outcomes. All tests are two-tailed and assessed at the 5% alpha-level. The statistical software used was SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Sample size

As RCTs for the use of ESP blocks in laparoscopic colonic surgery have not been published, an approximate scenario was established to obtain the required patient numbers. Calculations were based on the primary outcome (pain scores) and it was determined that a clinically meaningful difference between groups would be 2.5 points on the NRS. Assuming constant variance and a standard deviation of 3 points, a sample of 24 patients per group was required. The sample was inflated to 36 patients per group to account for intra-patient correlations arising from repeated measures. Thus, a total of 72 patients were required.

Randomisation

The randomisation schedule was generated by the Clinical Trials Division of the Pharmacy Department at The Queen Elizabeth Hospital. To ensure equal distribution of the intervention arm, randomisation was done in specific blocks to pre-determined numbers known only to the clinical trials division. A simple randomisation table was created by computer software (computerised sequence generation). This allocation was concealed by a sealed opaque envelope. The proceduralist was unable to be blinded; however, the patients were blinded to group allocation. The person analysing the data was also blinded.

Results

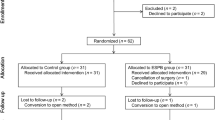

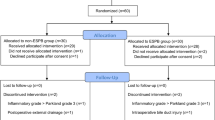

Seventy-two patients were recruited. Five patients did not complete the study and 67 were included in the analysis. These five patients excluded from analysis had a breach of protocol and none were lost to follow up (see Consort flow diagram Fig. 1). Table 1 shows the patient demographics in each group. Wound infiltration time was significantly lower than ESPB (p = < 0.01), otherwise both the groups were comparable with respect to pre-operative status and operative specifications are shown in Table 1. No block related complications, such as vascular/visceral puncture or local anaesthetic toxicity were recorded. None of the patients had well defined dermatomal spread in the ESPB group in PACU. Only one patient had patchy spread. Table 2 shows the pain scores and fentanyl use with mean and standard deviation by technique and time period, mean differences, 95% confidence intervals (CI) and comparison and global P values. There were no significant differences between the groups on intra-operative fentanyl use or total fentanyl use. There were also no significant differences between the groups for rest or cough pain scores or cumulative fentanyl use in PACU or on day one (refer to Table 2). The mean differences between ESP and WI groups for rest and cough pain ranged from − 0.6 to − 0.3 were not significant. Table 3 shows the complications. There was no difference in the complication incidences between the groups. Technically, we did not have any failures but had slight difficulty in three obese participants in the ESPB group requiring 120 mm needles to reach the plane. None of the patients had any sign or symptoms of LAST in the 24- h study period. However, 3 patients developed tachycardia after 48 h which was related to low haemoglobin requiring transfusion and anastomotic leak requiring intervention. One patient developed bradycardia (50/min) in the ESP group at 24 h on the ward, but remained stable. The average theatre time for (LA loading and checking/positioning/setup ultrasound equipment) was 20 min for ESP group compared to 10 min in WI group.

Discussion

The main outcome of the study was that we found no treatment- related differences in NRS pain scores at rest and coughing in PACU or day one between the groups. There was no statistically significant difference found in mean total fentanyl use between ESPB and WI groups. There were no differences in adverse events or length of stay between the groups. Though we hypothesised that ultrasound-guided ESP block is superior to wound infiltration in providing superior pain relief, this was not confirmed by our findings.

Technically, we did not have any failures but had slight difficulty in three obese participants in the ESPB group requiring 120 mm needles to reach the plane. Complications related to LAST were not observed. Only one patient in the ESPB group had bradycardia at 24 h on the ward, but remained haemodynamically stable with unremarkable ECG. Tulgar et al. found 3 mild cases of LAST in ESPB patients [12]. However, as stated, the patients in our study did not show any such symptoms. There were two patients in WI group who developed bradycardia, one in the PACU and the other outside the 24 h study period, both with unremarkable ECGs.

We performed ESPB at T8 level, however we did not observe any clinical effects on dermatome sensory distribution on the anterior aspect of the chest. We used 20 ml of 0.5% ropivacaine each side and it is possible that this may be an inadequate volume leading to poor sensory block. The optimal volume may range from 20 to 30 ml [13]. Tulgar et al. in their case series performed ESPB at T8 level for laparoscopic surgeries and reported its analgesic benefits but failed to report sensory block [8]. Similarly Chin et al. performed ESPB at T7 level in four patients undergoing laparoscopic ventral hernia repair and reported reduced pain scores in the first 24 h and oral morphine consumption [5]. They reported dermatome spread from T6 to T12 in one of their patients. In our study, though patients achieved analgesia, we did not observe any dermatomal sensory block. We are unable to explain this finding. Peng et al., described that the ESPB has characteristics of differential blockade [14]. Analgesia without motor block along discernible cutaneous sensory block has been described [14]. A review on dermatomal analysis of case reports revealed variable results of ESPB dermatomal spread [15]. Due to its unpredictable dermatomal spread more clinical trials are required to assess this. A recent narrative review reports that the mechanism of ESPB is from the direct effect of LA via physical spread and diffusion to ESP and adjacent tissue compartments [16, 17]. It also highlights the unpredictability and variability that result from myriad factors [16, 17].

This limited LA spread may be due to the mechanical barrier of the intertransverse ligament, intertransversalis muscle, and/or superior costotransverse ligaments in the thoracic paravertebral space [18]. Only intertransverse and superior costotransverse ligaments are found in the thoracic region posing a possible obstacle [19]. Some authors reported benefits of technical refinements of ESPB such as double injection technique, multiple level injections and injecting near the costotransverse ligament in breast procedures, to improve LA diffusion into the paravertebral space [20,21,22]. There are no published trials on these new approaches for performing ESPB in abdominal surgery. Future clinical trials on this should be considered. A metanalysis on ESP found reduction in postoperative opioid consumption compared to control [23]. However, this study had significant heterogeneity.

There were a few limitations of our trial: It was conducted in a single centre, was single blinded and practice of WI may not be applicable in other settings. As there were no RCTs, sample size calculation was not possible prior to commencement of this study. We were optimistic in requiring a 2.5 points difference in pain scores between the groups. Nevertheless, given our findings, even using a minimally clinically important difference (MCID) of only 1 point as suggested by Myles et al. [24] may not have changed our overall outcomes. However, a substantially lower MCID would have made our study with current numbers underpowered. The volume we used (20 ml) may be low, higher volumes may produce more extensive physical spread.

In conclusion, this prospective, single-centre, randomised, open label study revealed that both WI and ESPB techniques were comparable in terms of pain scores and rescue opioid requirement during the first 24 h post-operatively. There were no differences in complications observed between the two techniques. As the ESPB appears to be more invasive, and requires expertise, local anaesthetic wound infiltration remains a more practical and relatively simple technique in laparoscopic colonic surgery.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- WI:

-

Wound infiltration

- ESPB:

-

Erector Spinae Plane Block

- PACU:

-

Post anaesthetic care unit

- LA:

-

Local anaesthetic

- LAST:

-

Local anaesthetic systemic toxicity

- NRS:

-

Numerical Rating Score

- PCA:

-

Patient controlled analgesia

References

Forero M, Adhikary SD, Lopez H, Tsui C, Chin KJ. The erector spinae plane block: a novel analgesic technique in thoracic neuropathic pain. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2016;41(5):621–7.

Hamed MA, Goda AS, Basiony MM, Fargaly OS, Abdelhady MA. Erector spinae plane block for postoperative analgesia in patients undergoing total abdominal hysterectomy: a randomized controlled study original study. J Pain Res. 2019;12:1393–8.

Hamed MA, Yassin HM, Botros JM, Abdelhady MA. Analgesic efficacy of erector spinae plane block compared with intrathecal morphine after elective cesarean section: a prospective randomized controlled study. J Pain Res. 2020;13:597–604.

Ibrahim M, Elnabtity AM. Analgesic efficacy of erector spinae plane block in percutaneous nephrolithotomy: a randomized controlled trial. Anaesthesist. 2019;68(11):755–61.

Chin KJ, Adhikary S, Sarwani N, Forero M. The analgesic efficacy of pre-operative bilateral erector spinae plane (ESP) blocks in patients having ventral hernia repair. Anaesthesia. 2017;72(4):452–60.

Rao Kadam V, Currie J. Ultrasound-guided continuous erector spinae plane block for postoperative analgesia in video-assisted thoracotomy. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2018;46(2):243–5.

Restrepo-Garces CE, Chin KJ, Suarez P, Diaz A. Bilateral continuous erector spinae plane block contributes to effective postoperative analgesia after major open abdominal surgery: a case report. A A Case Rep. 2017;9(11):319–21.

Tulgar S, Selvi O, Kapakli MS. Erector spinae plane block for different laparoscopic abdominal surgeries: case series. Case Rep Anesthesiol. 2018;2018:3947281.

Aksu C, Gurkan Y. Ultrasound-guided bilateral erector spinae plane block could provide effective postoperative analgesia in laparoscopic cholecystectomy in paediatric patients. Anaesth Crit Care Pain Med. 2019;38(1):87–8.

Altiparmak B, Korkmaz Toker M, Uysal AI, Kuscu Y, Gumus Demirbilek S. Ultrasound-guided erector spinae plane block versus oblique subcostal transversus abdominis plane block for postoperative analgesia of adult patients undergoing laparoscopic cholecystectomy: randomized, controlled trial. J Clin Anesth. 2019;57:31–6.

Tulgar S, Kapakli MS, Senturk O, Selvi O, Serifsoy TE, Ozer Z. Evaluation of ultrasound-guided erector spinae plane block for postoperative analgesia in laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a prospective, randomized, controlled clinical trial. J Clin Anesth. 2018;49:101–6.

Tulgar S, Selvi O, Senturk O, Serifsoy TE, Thomas DT. Ultrasound-guided erector spinae plane block: indications, complications, and effects on acute and chronic pain based on a single-center experience. Cureus. 2019;11(1):e3815.

Choi YJ, Kwon HJ, Jehoon O, Cho TH, Won JY, Yang HM, et al. Influence of injectate volume on paravertebral spread in erector spinae plane block: an endoscopic and anatomical evaluation. PLoS One. 2019;14(10):e0224487.

Peng P, Finlayson R, Lee S, Bhatia A. Erector spinae plane block (ESP block). In: Ultrasound for interventional pain management. Baltimore: Springer; 2020. p. 131–48.

Tulgar S, Ahiskalioglu A, De Cassai A, Gurkan Y. Efficacy of bilateral erector spinae plane block in the management of pain: current insights. J Pain Res. 2019;12:2597–613.

Chin KJ, El-Boghdadly K. Mechanisms of action of the erector spinae plane (ESP) block: a narrative review. Can J Anaesth. 2021;68(3):387–408.

Chin KJ, Lirk P, Hollmann MW, Schwarz SKW. Mechanisms of action of fascial plane blocks: a narrative review. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2021;46(7):618–28.

Agur AM, Dalley AF. Grant’s atlas of anatomy. Switzerland: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2009.

Saadawi M, Layera S, Aliste J, Bravo D, Leurcharusmee P, Tran Q. Erector spinae plane block: a narrative review with systematic analysis of the evidence pertaining to clinical indications and alternative truncal blocks. J Clin Anesth. 2020;68:110063.

Aksu C, Kus A, Yorukoglu HU, Tor Kilic C, Gurkan Y. Analgesic effect of the bi-level injection erector spinae plane block after breast surgery: a randomized controlled trial. Agri Derg. 2019;31(3):132–7.

Cosarcan SK, Dogan AT, Ercelen O, Gurkan Y. Superior costotransverse ligament is the main actor in permeability between the layers? Target-specific modification of erector spinae plane block. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2020;45(8):674–5.

Sahin A, Gültekin A, Yildirım I, Baran O, Arar C. Ultrasound guided erector Spinae Block with costotransverse ligament puncture is more effective than erector Spinae Block alone; eight cases for oncologic breast surgery; a brief technical report. Open J Anesthesiol. 2020;10(05):179–89.

Kendall MC, Alves L, Traill LL, et al. The effect of ultrasound-guided erector spiane block on postsurgical pain: a met-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMC Anaesthesiol. 2020;20(1):99.

Myles PS, Myles DB, Galagher W, Boyd D, Chew C, MacDonald N, et al. Measuring acute postoperative pain using the visual analog scale: the minimal clinically important difference and patient acceptable symptom state. Br J Anaesth. 2017;118(3):424–9.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

VRK: Designing, ethics approval work, participant recruitment, obtaining consent, data collection, performing the regional blocks and coordinating the team. GL, RMvW, PH: Designing, supporting the researchers, drafting and editing the manuscript. SE: Statistical analysis drafting and editing the manuscript. VT: Designing the study, participant recruitment, drafting and editing. PW: Electronic data entry, blinding, drafting and editing. SA: Designing, supporting the researchers and drafting and editing the manuscript. The author(s) read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Institutional Human Ethics and Research Committee (HREC/18/CALHN/456), Central Adelaide Local Health Network approval obtained. Informed consent for participation was obtained from all participants prior to participation in the study.

The research meets ethical and scientific requirements in accordance with the NHMRC and relevant legislative policy and requirements.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

No Financial disclosures or conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Rao Kadam, V., Ludbrook, G., van Wijk, R.M. et al. A comparison of ultrasound guided bilateral single injection shot Erector Spinae Plane blocks versus wound infiltration for post-operative analgesia in laparoscopic assisted colonic surgery- a prospective randomised study. BMC Anesthesiol 21, 255 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12871-021-01474-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12871-021-01474-8