Abstract

Background

Individualized fluid management (IFM) has been shown to be useful to improve the postoperative outcome of patients undergoing major abdominal surgery. A limited number of clinical studies have been done in orthopaedic patients and have yielded conflicting results. We designed the present study to investigate the clinical impact of IFM in patients undergoing major spine surgery.

Methods

This is a before-after study done in 300 patients undergoing posterior spine arthrodesis. Postoperative outcomes were compared between control group implementing standard fluid management (n = 150) and IFM group (n = 150) guided by fluid protocol based on continuous stroke volume monitoring and optimization. The primary outcome measure was the proportion of patients who developed one or more complications within 30 days following surgery.

Results

During surgery, patients received on average the same volume of crystalloids (7.4 vs 7.2 ml/kg/h) and colloids (1.6 vs 1.6 ml/kg/h) before and after the implementation of IFM. During 30 days following surgery, the proportion of patients who developed one or more complications was lower in the IFM group (32 vs 48%, p < 0.01). This difference was mainly explained by a significant decrease in post-operative nausea and vomiting (from 38 to 19%, p < 0.01), urinary tract infections (from 9 to 1%, p < 0.01) and surgical site infections (from 5 to 1%, p < 0.05). Median hospital length of stay was not affected by the implementation of IFM.

Conclusion

In patients undergoing major spine surgery, the implementation of IFM was associated with a significant decrease in postoperative morbidity.

Trial registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02470221. Prospectively registered on June 12, 2015.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Intraoperative fluid management is a major determinant of postoperative outcome in various types of surgery [1,2,3]. Both insufficient and excessive fluid administration are associated with adverse events [4, 5]. In patients undergoing major surgery, individualized fluid management (IFM) has been proposed to tailor fluid administration to individual needs [2, 3]. Multicentre randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and meta-analyses suggest that IFM is beneficial in decreasing postoperative morbidity, shortening hospital length of stay and saving costs [6,7,8,9,10,11]. Most IFM studies have been conducted in patients undergoing major gastro-intestinal surgery [10,11,12]. A limited number of studies have been done among patients undergoing orthopaedic surgery and have yielded conflicting results. For instance, in patients undergoing hip fracture surgery, a few studies [13, 14] reported clinical benefits when using IFM, whereas others did not [15, 16]. In addition, it remains unclear whether clinical benefits reported by RCTs are reproducible in real life conditions. The implementation of IFM require education, experience in using hemodynamic monitoring tools, as well as focus and time during the procedure to ensure optimal protocol adherence.

Spine surgery represents a particularly challenging setting for intraoperative fluid management. Prone positioning during the surgery is associated with physiological changes and the surgery itself is associated with significant intraoperative blood loss and postoperative complications [17,18,19]. Surprisingly, little is known about the impact of IFM in this specific context. Therefore, we designed a before-after comparison study to investigate the impact of IFM implementation on the postoperative outcome of patients undergoing major spine surgery.

Methods

Study design and participants

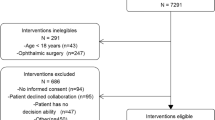

This non-randomized controlled study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Peking Union Medical College Hospital and was registered at clinicaltrials.gov (NCT02470221). Written informed consent was obtained from all patients. We studied consecutive adult patients undergoing posterior spine arthrodesis involving more than three vertebral spaces at Peking Union Medical College Hospital. Patients who met any of the following criteria were excluded: emergency surgery, New York Heart Association (NYHA) functional classification class IV or higher, severe aortic regurgitation, inability to cooperate or to sign informed consent.

The study comprised 2 phases. During the first phase (Control group) the use of fluids, vasoactive and inotropic drugs were at the discretion of the anaesthesiologist. During the second phase, hemodynamic management was conducted according to an IFM protocol based on stroke volume monitoring and optimization (IFM group). Before initiating the second phase, members of our clinical staff were trained to become familiar with the hemodynamic monitoring technique and the IFM protocol.

Anaesthesia and surgical management

General anaesthesia was induced by propofol, fentanyl and rocuronium and maintained with target-controlled infusion of propofol (plasma concentration of 3-5 mg ml/L). After tracheal intubation, patients were ventilated in a volume-controlled mode with a tidal volume of 8 ml/kg. In both groups, a 20 G radial arterial line was inserted for continuous arterial pressure monitoring. The recommendation was to maintain mean arterial pressure ≥ 80% of baseline, with a heart rate ranging between 50 and 100 bpm. Blood transfusion was recommended to maintain haemoglobin > 9 g dl/L.

After anaesthesia induction, all patients were placed in the prone position supported by 4 pads (2 pads under the shoulders and 2 under pelvic sites) to suspend the chest and abdomen from the operation bed. All surgical procedures were performed by the same group of experienced spine surgeons.

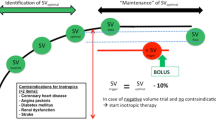

Individualized fluid management

In the IFM group (from April 2017) the radial line was connected to the fourth-generation Vigileo/Flotrac system (Edwards Lifesciences, Irvine, CA, USA) enabling continuous monitoring of stroke volume from pulse contour analysis. Fluid maintenance was set at 3 ml/kg/hr. of Ringer’s lactate. Once patients were in the prone position, we started to monitor stroke volume and a bolus of 3 ml/kg of Ringer’s lactate was administered over a 5 min period. The fluid bolus was repeated in responder patients (increase in stroke volume > 10%) until the plateau of the Frank-Starling relationship was reached (increase in stroke volume < 10%). During surgery, additional boluses were given only if stroke volume dropped by > 10% below the plateau value. In case of hypotension (mean arterial pressure < 80% from baseline) in fluid non-responders, vasopressors were recommended. The IFM protocol is summarized in Fig. 1. This fluid management strategy has been used with success in a recent multicentre IFM study [8] and has been recommended in published consensus statements and by national guidelines [20, 21]. Adherence to the IFM protocol was strongly encouraged but not tracked nor quantified.

Outcome variables

The primary outcome measure was the proportion of patients who developed one or more complications within 30 days following surgery (aka postoperative morbidity). Postoperative complications included gastro-intestinal complications (nausea and vomiting, ileus), infectious complications (urinary tract infection, surgical site infection, pneumonia, bloodstream infection), cardiac complications (cardiac arrest, myocardial infarction, heart failure, arrhythmia requiring pharmacologic treatment, hypotension requiring vasopressor administration, pulmonary embolism, deep venous thrombosis, stroke), and other complications (prolonged mechanical ventilation > 48 h, acute respiratory distress syndrome, acute renal failure according to KDIGO criteria). Diagnosis and management of postoperative complications were undertaken by non-research staff according to our local practice. Postoperative hospital length of stay and mortality were also recorded.

Sample size calculation and statistical analysis

Based on the 60% postoperative morbidity rate observed in a sample population from our institution, a power analysis indicated that a sample size of around 150 patients in each group was required to show a 25% relative reduction (from 60 to 45%) in postoperative morbidity after IFM implementation, with a power of 0.8 and a type 1 error (α) = 0.05.

Continuous normally distributed variables are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD), and non-normally distributed continuous variables are expressed as medians (interquartile ranges). Categorical variables are expressed as numbers and percentages. An independent sample t-test was used to test differences between groups for continuous normally distributed variables, a Chi-square test was used for categorical data to test for differences between groups. When data were not normally distributed, a Mann-Whitney U test was used to analyse differences between groups. The multivariate analysis estimated the association between primary outcomes (composite complication defined as number of patients developing more than one complications) and implementation of IFM controlling for age, sex, American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) score, history of hypertension, diabetes mellitus and coronary artery disease using logistic regression modelling. Statistical analysis was performed with SPSS, version 23 (IBM Corp. USA) or STATA, version 14 (Stata Corp. USA). All statistical tests were two-sided, and p < 0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance.

Results

Baseline characteristics

Three hundred patients were enrolled between October 2016 and September 2017, 150 patients in the Control group between October 2016 and March 2017, and 150 patients in the IFM group from April to September 2017. Patient characteristics including age, gender, body mass index (BMI), comorbidities and ASA score were not significantly different between the Control and the IFM group (Table 1).

Intraoperative fluid management

During surgery, both groups (Control and IFM) received the same average amount of crystalloid and colloids (Table 2). Estimated blood loss and urine output were comparable as well (Table 2). As a result, the intraoperative fluid balance was not different between Control and IFM patients (Table 2).

Postoperative outcomes

Overall, less patients developed one or more complications (32 vs 48%) in the IFM group (Table 3). The proportion of patients who developed postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV), urinary tract and surgical site infections was significantly lower in the IFM group than in the control group (Table 3). Hospital length of stay was comparable in both groups (Table 3). None of the 300 patients died within the 30 days following surgery. Upon multivariate analysis (Table 4) implementation of IFM demonstrated statistically significant associations with postoperative composite complications after controlling for age, sex, ASA score, BMI and comorbidities (OR = 0.481, 95% CI 0.295 to 0.786, P = 0.003).

Discussion

Our study demonstrated that the implementation of IFM for patients undergoing major spine surgery was possible and effective in our institution. Indeed, it was associated with a significant reduction in postoperative morbidity.

Our findings are consistent with the results of several RCTs and meta-analyses which have demonstrated that IFM is susceptible to improve the postoperative outcome of patients undergoing major surgery, and in particular to decrease PONV [22, 23] urinary tract and surgical site infections [6, 24, 25]. However, the beneficial effects of IFM have been questioned in patients undergoing orthopaedic surgery. In patients undergoing hip fracture surgery, two small studies (< 100 patients) have reported shorter times to being declared medically fit for discharge when using IFM [13, 14]. But more recent and larger studies did not confirm the clinical benefits of IFM in this surgical patient population [15, 16]. Significant reductions in postoperative complications with IFM have also been reported in a small RCT done in 40 patients undergoing primary hip surgery [26] and in a larger study of patients undergoing hip revision [27]. Peng et al. [28] observed a significant improvement in gastro-intestinal function with IFM in a RCT of 80 orthopaedic patients, where 34 of them underwent spine surgery. Therefore, our study is the largest evaluation of IFM in orthopaedic patients and the first one with a focus on spine surgery.

Interestingly, total intraoperative fluid volumes were not significantly different between the Control and the IFM group. At first sight, it may appear somewhat surprising to observe differences in postoperative outcome without observing differences in the volume of fluid administered during surgery. Actually, this finding is consistent with the results of recent multicenter studies [8] and meta-analyses [12]. Indeed, it has been hypothesized that the individualization of fluid therapy is effective through timely replenishment of fluid for patients who are fluid responders and avoidance of fluid overload for those who are not [10]. With the guidance of IFM protocol, fluid responders are more likely to receive more fluid and non-responders more likely to receive less. This may explain why the average volume of fluid was comparable between groups.

The decrease in postoperative complications was not associated with a significant decrease in hospital length of stay. Several reasons could explain this finding. First, the implementation of IFM was associated with a significant decrease in minor complications, which are less likely to impact length of stay than major complications. Second, hospital discharge depends not only on postoperative complications but also on cultural and logistic factors such as the agreement from the patient or their family, as well as the availability of a structure for re-education. In this respect, several IFM studies have reported a significant decrease in postoperative complications that was not associated with a significant reduction in hospital length of stay [7, 29].

Our study has limitations. Because it was not an RCT, we cannot claim causality between IFM implementation and the observed decrease in postoperative morbidity [30]. Another potential disadvantage of this study design is the risk of imbalance between groups. Luckily, given the size of our study (300 patients), there was no visible difference at baseline between the Control and the IFM groups. Randomized controlled trials are essential research tools with strong internal validity but low generalizability to real life conditions [30,31,32]. In contrast, before after comparison studies provide valuable data regarding the effect of an intervention in real-life conditions, rather than under the stringent conditions of a RCT [30, 31]. Similar study design has been used in several landmark studies which had a significant impact on quality of surgical and critical care [33, 34]. In addition, several quality improvement programs have confirmed the clinical value of IFM in patients undergoing major abdominal surgery [35,36,37,38]. However, to the best of our knowledge, our study is the first real life evaluation of IFM in patients undergoing spine surgery. We did not use tracking tools or target screens to quantify and optimize compliance to our IFM protocol. We are well aware that such tools are now available on modern hemodynamic monitoring systems [39] but they were not on our Vigileo monitor. In addition, diagnosis of postoperative complications was carried out by non-research staff according to our institutional practice, so that there was no official definition for each complication during the study period. Finally, monitoring equipment would increase costs which may be a barrier to hospital adoption [40,41,42]. Cost-effectiveness is an important consideration [42, 43]. Unfortunately, in this study we were unable to assess the impact of IFM implementation on health care costs.

Conclusions

In patients undergoing major spine surgery, the implementation of IFM was associated with a significant decrease in postoperative complications that, however, did not impact hospital length of stay. Further studies are required to assess the economic impact.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- IFM:

-

Individualized fluid management

- RCTs:

-

randomized controlled trials

- ASA:

-

American Society of Anesthesiologists

- NYHA:

-

New York Heart Association

- PONV:

-

postoperative nausea and vomiting

- Hb:

-

Haemoglobin

- HR:

-

Heart rate

- SBP:

-

Systolic blood pressure

- ICU:

-

Intensive care unit

- ARDS:

-

Acute respiratory distress syndrome

References

Bellamy MC. Wet, dry or something else? Br J Anaesth. 2006;97:755–7.

Michard F, Biais M. Rational fluid management: dissecting facts from fiction. Br J Anaesth. 2012;108:369–71.

Miller TE, Myles PS. Perioperative fluid therapy for major surgery. Anesthesiology. 2019;130:825–32.

Myles P, Bellomo R, Corcoran T, et al. Restrictive versus Liberal fluid therapy for major abdominal surgery. N Engl J Med. 2018;378:2263–74.

Doherty M, Buggy DJ. Intraoperative fluids: how much is too much? Br J Anaesth. 2012;109:69–79.

Scheeren TW, Wiesenack C, Gerlach H, Marx G. Goal-directed intraoperative fluid therapy guided by stroke volume and its variation in high-risk surgical patients: a prospective randomized multicentre study. J Clin Monit Comput. 2013;27:225–33.

Salzwedel C, Puig J, Carstens A, et al. Perioperative goal-directed hemodynamic therapy based on radial arterial pulse pressure variation and continuous cardiac index trending reduces postoperative complications after major abdominal surgery: a multi-center, prospective, randomized study. Crit Care. 2013;17:R191.

Calvo-Vecino JM, Ripolles-Melchor J, Mythen MG, et al. Effect of goal-directed haemodynamic therapy on postoperative complications in low-moderate risk surgical patients: a multicentre randomised controlled trial (FEDORA trial). Br J Anaesth. 2018;120:734–44.

Pearse RM, Harrison DA, MacDonald N, et al. Effect of a perioperative, cardiac output-guided hemodynamic therapy algorithm on outcomes following major gastrointestinal surgery: a randomized clinical trial and systematic review. Jama. 2014;311:2181–90.

Perel A. Perioperative goal-directed therapy with uncalibrated pulse contour methods: impact on fluid management and postoperative outcome. Br J Anaesth. 2017;119:541–3.

Chong M, Wang Y, Berbenetz N, McConachie I. Does goal-directed haemodynamic and fluid therapy improve peri-operative outcomes?: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2018;35:7.

Michard F, Giglio MT, Brienza N. Perioperative goal-directed therapy with uncalibrated pulse contour methods: impact on fluid management and postoperative outcome. Br J Anaesth. 2017;119:22–30.

Sinclair S, James S, Singer M. Intraoperative intravascular volume optimisation and length of hospital stay after repair of proximal femoral fracture: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 1997;315:909–12.

Venn R, Steele A, Richardson P, Poloniecki J, Grounds M, Newman P. Randomized controlled trial to investigate influence of the fluid challenge on duration of hospital stay and perioperative morbidity in patients with hip fractures. Br J Anaesth. 2002;88:65–71.

Moppett IK, Rowlands M, Mannings A, Moran CG, Wiles MD. LiDCO-based fluid management in patients undergoing hip fracture surgery under spinal anaesthesia: a randomized trial and systematic review. Br J Anaesth. 2015;114:444–59.

Bartha E, Arfwedson C, Imnell A, Fernlund M, Andersson L, Kalman S. Randomized controlled trial of goal-directed haemodynamic treatment in patients with proximal femoral fracture. Br J Anaesth. 2013;110:545–53.

Street JT, Lenehan BJ, DiPaola CP, et al. Morbidity and mortality of major adult spinal surgery. A prospective cohort analysis of 942 consecutive patients. The spine journal : official journal of the North American Spine Society. 2012;12:22–34.

Lee MJ, Cizik AM, Hamilton D, Chapman JR. Predicting medical complications after spine surgery: a validated model using a prospective surgical registry. Spine J. 2014;14:291–9.

Kasparek MF, Boettner F, Rienmueller A, et al. Predicting medical complications in spine surgery: evaluation of a novel online risk calculator. Eur Spine J. 2018;27:2449–56.

Navarro LH, Bloomstone JA, Auler JO Jr, et al. Perioperative fluid therapy: a statement from the international Fluid Optimization Group. Perioper Med (London, England). 2015;4:3.

Vallet B, Blanloeil Y, Cholley B, Orliaguet G, Pierre S, Tavernier B. Guidelines for perioperative haemodynamic optimization. Annales francaises d'anesthesie et de reanimation. 2013;32:e151–8.

Giglio MT, Marucci M, Testini M, Brienza N. Goal-directed haemodynamic therapy and gastrointestinal complications in major surgery: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Br J Anaesth. 2009;103:637–46.

Gan TJ, Soppitt A, Maroof M, et al. Goal-directed intraoperative fluid administration reduces length of hospital stay after major surgery. Anesthesiology. 2002;97:820–6.

Dalfino L, Giglio MT, Puntillo F, Marucci M, Brienza N. Haemodynamic goal-directed therapy and postoperative infections: earlier is better. A systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care. 2011;15:R154.

Yuan J, Sun Y, Pan C, Li T. Goal-directed fluid therapy for reducing risk of surgical site infections following abdominal surgery - a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Int J Surg. 2017;39:74–87.

Cecconi M, Fasano N, Langiano N, et al. Goal-directed haemodynamic therapy during elective total hip arthroplasty under regional anaesthesia. Crit Care. 2011;15:R132.

Habicher M, Balzer F, Mezger V, et al. Implementation of goal-directed fluid therapy during hip revision arthroplasty: a matched cohort study. Perioper Med (London, England). 2016;5:31.

Peng K, Li J, Cheng H, Ji FH. Goal-directed fluid therapy based on stroke volume variations improves fluid management and gastrointestinal perfusion in patients undergoing major orthopedic surgery. Med Princ Pract. 2014;23:413–20.

Benes J, Giglio M, Brienza N, Michard F. The effects of goal-directed fluid therapy based on dynamic parameters on post-surgical outcome: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Crit Care. 2014;18:584.

Portela MC, Pronovost PJ, Woodcock T, Carter P, Dixon-Woods M. How to study improvement interventions: a brief overview of possible study types. BMJ Qual Saf. 2015;24:325–36.

Saturni S, Bellini F, Braido F, et al. Randomized controlled trials and real life studies. Approaches and methodologies: a clinical point of view. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2014;27:129–38.

Vincent JL. We should abandon randomized controlled trials in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2010;38:S534–8.

Haynes AB, Weiser TG, Berry WR, et al. A surgical safety checklist to reduce morbidity and mortality in a global population. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:491–9.

Pronovost P, Needham D, Berenholtz S, et al. An intervention to decrease catheter-related bloodstream infections in the ICU. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2725–32.

Cannesson M, Ramsingh D, Rinehart J, et al. Perioperative goal-directed therapy and postoperative outcomes in patients undergoing high-risk abdominal surgery: a historical-prospective, comparative effectiveness study. Crit Care. 2015;19:261.

Veelo DP, van Berge Henegouwen MI, Ouwehand KS, et al. Effect of goal-directed therapy on outcome after esophageal surgery: a quality improvement study. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0172806.

Jin J, Min S, Liu D, Liu L, Lv B. Clinical and economic impact of goal-directed fluid therapy during elective gastrointestinal surgery. Perioper Med (London, England). 2018;7:22.

Lima MF, Mondadori LA, Chibana AY, Gilio DB, Giroud Joaquim EH, Michard F. Outcome impact of hemodynamic and depth of anesthesia monitoring during major cancer surgery: a before-after study. J Clin Monit Comput. 2019;33:365–71.

Michard F. Decision support for hemodynamic management: from graphical displays to closed loop systems. Anesth Analg. 2013;117:876–82.

Bartha E, Davidson T, Hommel A, Thorngren KG, Carlsson P, Kalman S. Cost-effectiveness analysis of goal-directed hemodynamic treatment of elderly hip fracture patients: before clinical research starts. Anesthesiology. 2012;117:519–30.

Sadique Z, Harrison DA, Grieve R, Rowan KM, Pearse RM. Cost-effectiveness of a cardiac output-guided haemodynamic therapy algorithm in high-risk patients undergoing major gastrointestinal surgery. Perioper Med (London, England). 2015;4:13.

Michard F, Mountford WK, Krukas MR. Potential return on investment for implementation of perioperative goal-directed fluid therapy in major surgery: a nationwide database study. Perioper Med (London, England). 2015;4:11.

Eappen S, Lane BH, Rosenberg B, et al. Relationship between occurrence of surgical complications and hospital finances. JAMA. 2013;309:1599–606.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. F Michard from MiCo, Switzerland, for scientific discussions and help for manuscript preparation.

Funding

This project is supported by Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences Innovation Fund for Medical Sciences (Grant No. 2016-I2M-3-024). This grant is issued by Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences which is a governmentally owned medical educational and research facility. This grant is designed to support medical innovation research project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

LC and LX contributed to study conception and design, acquisition of data; XL was responsible for drafting the article or revising it critically for important intellectual content; YLZ derived the models and was responsible for analysis and interpretation of data. YGH and XHZ made substantial contribution to conception and design of the protocol and supervised the study. LC LX made final approval of the version to be published. The authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This non-randomized controlled study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Peking Union Medical College Hospital and was registered at clinicaltrials.gov (NCT02470221). Written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Che, L., Zhang, X.H., Li, X. et al. Outcome impact of individualized fluid management during spine surgery: a before-after prospective comparison study. BMC Anesthesiol 20, 181 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12871-020-01092-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12871-020-01092-w