Abstract

Background

Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy (LC) is conventionally performed under general anaesthesia (GA), but there are multiple studies which have found spinal anaesthesia (SA) as a safe alternative. This meta-analysis was performed after adding many recent randomized controlled trials (RCTs) to clarify this issue.

Methods

Relevant articles published in English were identified by searching PubMed, Embase, Web of Knowledge, and the Cochrane Controlled Trial Register from January 1, 2000 to December 1, 2014. Reference lists of the retrieved articles were reviewed to identify additional articles. Primary outcomes (postoperative pain scores) and secondary outcomes (operating time (OT) and postoperative complications) were pooled. Quantitative variables were calculated using the weighted mean difference (WMD), and qualitative variables were pooled using odds ratios (OR).

Results

Seven appropriate RCTs were identified from 912 published articles. Seven hundred and twelve patients were treated, 352 in SA group and 360 in GA group. LC under SA was superior to LC under GA in postoperative pain within 12 h (visual analogue score (VAS) in 2–4 h, WMD = −1.61, P = 0.000; VAS in 6–8 h, WMD = −1.277, P = 0.015) and postoperative complications (postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) WMD = 0.427, P = 0.001; Overall Morbidity WMD = 0.691, P = 0.027). The GA group was superior to SA group in postoperative urinary retention (WMD = 4.273, P = 0.022). There were no significant differences in operating time (WMD = 0.184, P = 0.141) between two groups.

Conclusions

SA as the sole anaesthesia technique is feasible, safe for elective LC.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) has become the gold standard for the surgical treatment of symptomatic cholelithiasis and has gained worldwide acceptance [1]. It is a minimally invasive procedure with a significantly shorter hospital stay and a quicker convalescence compared with the classical open cholecystectomy [2].

LC is conventionally done under general anaesthesia (GA) and may be associated with postoperative pain and nausea and vomiting (PONV). Rodgers et al., published a meta-analysis showing that the use of neuraxial techniques for a variety of surgical procedures resulted in a decrease in mortality, venous thromboembolism, myocardial infarction, and several other complications [3]. Spinal anesthesia (SA) is a commonly used anaesthetic technique that has a very good safety profile. SA has several advantages over GA. These advantages include the patients’ being awake and oriented at the end of the procedure, less postoperative pain, and the ability to ambulate earlier than patients receiving general anesthesia. Moreover, the incidences of nausea and vomiting are less with selective spinal anesthesia than with general anesthesia [4]. SA is more effective than GA in blunting the neuroendocrine stress and adverse responses to surgery [5]. Some possible problems related to the technique of general anesthesia such as teeth and oral cavity damage during laryngoscopy, sore throat, and pain related to intubation and/or extubation are prevented by administering selective spinal anesthesia to patients undergoing laparoscopic interventions [6]. There are multiple reports that have been published regarding the feasibility of SA for LC in patients fit for GA [7–13].

Surprisingly, in the era of minimally invasive medicine, regional anesthesia has not gained popularity and has not been routinely used as a sole method of anesthesia in laparoscopic procedures. Johnson noted that “all laparoscopic procedures are merely a change in access and still require general anesthetic; hence the difference from conventional surgery is likely to be small” [14]. This statement is predominantly based on the assumption that laparoscopy necessitates endotracheal intubation to prevent aspiration and respiratory distress secondary to the induction of carbon dioxide pneumoperitoneum, which is not well tolerated in a patient who is awake during the procedure [4, 15, 16].

These contradictions make it necessary to more closely compare SA and GA in LC, to evaluate whether SA in LC is associated with better results. This comprehensive meta-analysis included many recent randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and was systematically conducted to verify whether SA superior to GA for laparoscopic cholecystectomy or not.

Methods

A meta-analysis protocol was drafted before the initial search was started. The meta-analysis was conducted and reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement issued in 2009 [17].

Literature search

We searched PubMed, Web of Knowledge, Embase and the Cochrane Controlled Trial Register to identify relevant articles published from January 1, 2000 to December 1, 2014 using the search phrases (((((regional anaesthesia) OR regional anesthesia) OR spinal) OR general anesthesia)) AND (((((laparoscop* or celioscop* or coelioscop* or abdominoscop* or peritoneoscop*) AND cholecystecto* or colecystecto*)) OR “Cholecystectomy, Laparoscopic)). Appropriate adjustments were required according to the database. Filters were used in PubMed, Embase and Web of Knowledge to exclude animal and non-English studies. A manual search of published meta-analyses and relevant articles was performed to identify additional articles.

Article selection

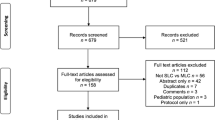

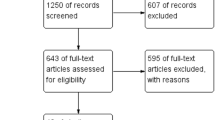

The process of article selection was based on the PRISMA flow diagram [15]. Selected studies met the following criteria: (a) RCT design; (b) compared SA and GA; (c) revealed at least one of the primary or secondary outcomes mentioned below; and (d) were published in English. Articles were excluded if: (a) the surgery was not cholecystectomy; (b) spinal anesthesia was not mentioned; (c) it was a retrospective study, prospective nonrandomized study, animal study, review, letter, meeting, or comment. When multiple published articles from the same study were available, the report with the most detailed information was selected.

Data extraction

Primary outcomes evaluated included postoperative pain score. Pain scores from RCTs using a visual analogue scale/score (VAS) were pooled to assess postoperative abdominal pain. Three postoperative time points were used to evaluate pain, 2 to 4 h, 6 to 8 h, and 24 h.

Secondary measures evaluated included intraoperative outcomes (Operating time, Intraoperative Events), postoperative complications (Nausea and Vomiting, Urinary retention and Overall Morbidity). Intraoperative Events (events occurring during spinal anaesthesia included hypotension, right shoulder pain, Nausea and Vomiting).

Overall Morbidity is that the morbidity which each included studies reported were pooled by meta analyze.

Patient characteristics (number of patients, gender, age and body mass index) were also recorded. If the above data was not available in the published study, the authors were contacted and asked to supply the information.

Assessment of study quality

The literature search, article selection, data extraction and assessment of study quality were completed independently by two authors (Gan and Qin). Discrepancies were resolved by discussion. When a consensus could not be reached, a third author (Li) broke the tie. Quality assessment was independently conducted in all the included studies by three investigators (Gan, Qi and Li.) using the Jadad’s revised rating scale [18]. Disagreements were resolved by discussion. Jadad’s revised rating scale comprised of four parameters of quality: Generate (0–2 points), Hide (0–2 points), Double Blinding (0–2 points) and Withdraws And Dropouts (0–1 points). The maximum possible score is 7 points and Jadad’s scores ≥4 are considered as high-quality studies.

Statistical analysis

Continuous variables were combined using the weighted mean difference (WMD). The method of Hozo et al. [19] was used if variables were provided as medians or/and ranges instead of a mean with a standard deviation. Binary variables were pooled using an odds ratio (OR). Homogeneous data was evaluated using fixed effect models. The inverted variance method was used for continuous variables and the Mantel-Haenszel method for binary variables. Random effect models based on the DerSimonian & Laird method were used to calculate the combined outcomes of both continuous and binary variables when heterogeneity existed. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Heterogeneity was identified using a chi-square-based Q-test (P ≤ 0.10) and I2 index (I2 exceeding 50 %). If heterogeneity was found, a meta-regression based on the Restricted Maximum Likelihood (REML) method was conducted to identify any related factors (P < 0.05 was considered significant). Subgroup analyses were conducted to identify potential sources of heterogeneity when the meta-regression was not adequate (less than 10 studies reported the outcome) or as a supplementary method. Sensitivity analyses were performed to examine the effect of excluding lower quality studies. Publication bias was evaluated using Egger’s regression test, with P < 0.05 indicating statistically significant publication bias. The confidence interval (CI) was established at 95 %. Statistical analyses were carried out using Stata12.0 software (Stata Corporation, USA).

Results

Identification of studies and quality of the RCTs

Nine RCTs [1, 10, 12, 20–25] were extracted from 1230 publications identified from databases and other sources. The PRISMA [15] flow diagram for this meta-analysis is presented in Fig. 1. Two studies [24, 25] were called randomized without defining the method of randomization or blinding and whether patients withdrew or dropped out. Only seven high-quality [1, 10, 12, 20–23] articles were included in the meta-analysis.

Characteristics of included RCTS

Seven hundred and twelve patients (352 with SA, 360 with GA) were identified to be included in the meta-analysis. Table 1 shows the general characteristics, including sample size, M/F ratio, age, and body mass index (BMI). There was no significant difference in number of patients, Male/Female ratio, Age and BMI between groups.

Quantitative synthesis

Primary outcomes

The postoperative pain scores were assessed in 7 studies (Table 2). Table 3 summarizes the pooled results of the VASs. VASs from postoperative 2 to 4 h and 6 to 8 h were significantly lower after LC under SA (P = 0.000 and P = 0.015, respectively). There were no significant differences in VASs at 24 h (P = 0.17). Forest plots of primary outcomes are listed in (Figs. 2, 3 and 4).

Secondary outcomes

Seven studies reported OT (Table 4). There were no significant differences in OT (P = 0.14). Pooled results of OT are listed in Table 5. Seven studies reported Intraoperative Events (Table 4). In the SA group 6 studies reported shoulder pain. Five studies reported Nausea and Vomiting, Six studies reported Hypotension. Forest graphs for intraoperative outcomes are shown in Fig. 5.

Six articles included in the meta-analysis showed complication, but only one study did not give the exact figures of complication. There were also significant differences in PONV, Urinary retention and Overall Morbidity (P < 0.05) (Table 5). There were no deaths in any of the included RCTs. Forest graphs for postoperative complications are shown in (Figs. 6, 7 and 8).

Test of heterogeneity

The results of heterogeneity testing are summarized in Tables 3 and 5. Significant heterogeneity existed in primary outcomes. We evaluated study quality and general characteristics of the included studies as potential sources of methodological and clinical heterogeneity. Meta-regressions were performed for postoperative pain scores to assess the potential reasons.

A standard four-trocar technique of LC was followed in all articles, and all selected studies met the following exclusion criteria: (a) patients with acute cholecystitis, and (b) previous upper abdominal surgeries. So subgroup analyses were conducted by stratifying study quality (high-quality vs. low-quality) to verify the accuracy of the meta-regression and assess the possible sources of heterogeneity. There were no significance sources of methodological and clinical heterogeneity identified by the meta-regression and subgroup analyses (Data not shown).

Sensitivity analysis and publication bias

Sensitivity analysis was conducted to assess the effect of study quality. Only VAS from postoperative 6 to 8 h were affected by low quality of study (Data not shown). After low-quality studies were excluded, there was no statistically difference in VAS from postoperative 6 to 8 h. Statistical publication bias was detected for VAS in three time points, according to Egger’s test (P < 0.05) (Tables 3 and 5).

Discussion

The less postoperative pain within 12 h and postoperative complications were found in SA group. There was no significant difference between SA group and GA group in regard to OT and postoperative pain in 24 h.

There were several limitations to this study. The meta-regression and subgroup analyses we performed did not account for all the sources of heterogeneity, which existed in the great majority of continuous variables (Tables 3 and 5). Random effects models were used when heterogeneity existed, although the stability of the pooled analyses could not be affirmed. There was also publication bias in some of the outcomes. One potential reason is that no withdrawals or dropouts were reported in the some of articles, and Jadad’s revised rating scale for the RCTs was low. Finally, we performed an electronic search and a manual search in order to identify any potentially relevant articles. We may have missed some meaningful articles, especially those not in English.

A major focus of this study was to determine which anesthesia method was associated with the least postoperative pain. In our meta-analyses, we found a significant difference in the VAS scores at postoperative 2 to 4 h and 6 to 8 h. The reduced pain in the SA group may be due to a persistent neuraxial blockade by SA. The postoperative VASs could be influenced by intraperitoneal pressure, use of local anesthetics, peritoneal irrigation, psychological factors and type of incision [26–28]. These factors could also contribute to heterogeneity. Although all of RCTs reported a postoperative pain score, different time points and methods were used (Table 4). The presence of heterogeneity and publication bias prevented identification of a superior anesthetic technique. Future prospective double-blind randomized controlled studies will need to address the issue of postoperative pain at different time points.

Although, recent studies have shown that laparoscopy in patients with regional anaesthesia may be tolerated well, shoulder tip pain can be a significant intraoperative problem. The reported incidence for intraoperative right-shoulder pain in previous studies requiring iv fentanyl administration ranged from 10 to 55.2 % [9–13]. Referred pain to right shoulder is probably due to irritation of diaphragm by the CO2 pneumoperitoneum [29]. In the our study, 92 patients (26.1 %) complained of shoulder pain.

Intraoperative hypotension is another problem for LC

Under spinal anesthesia [3, 8] 74 (21 %) patients developed hypotension during operation in our study. Intravenous ephedrine injection solved this problem in all patients. In-traoperative hypotension is a common problem for patients undergoing LC under spinal anesthesia, but intravenous ephedrine injection is a very effective treatment.

In our study there was no statistically significant difference in mean operative time between the SA gand GA groups suggesting that SA in LC did not interfere either the adequacy of the surgical view or access thus not prolonging the operative time significantly.

Postoperative nausea and vomiting are relatively common after LC under general anesthesia [30]. In other series where LC was applied under spinal anesthesia, nausea and vomiting were not common [7, 8]. The surgical technique of LC was not different in spinal anesthesia compared to general anesthesia. Thus, the low incidence of nausea and vomiting seems to be related to the spinal approach.

In our meta-analyses, we found a significant higher incidence of Postoperative urinary retention in SA group. This is known to be related to regional anesthesia with rates of up to 20 % in some series [31].

We also found a significant difference in overall morbidity. Patients may have had less incidence of postoperative complications in SA group suggesting that LC under SA is safe.

Conclusion

This study confirms the feasibility and safety of spinal anaesthesia as the sole anaesthesia technique for elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy. There was not enough data to support SA as the standard of care as it has small number of the cases. A large prospective double-blind randomized controlled trial comparing SA and GA in LC is needed to identify the best procedure.

References

Bessa SS, Katri KM, Abdel-Salam WN, El-Kayal SA, Tawfik TA. Spinal versus general anesthesia for day-case laparoscopic cholecystectomy: A prospective randomized study. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech. 2012;22:550–5.

Keus F, De Jong JAF, Gooszen HG, Van Laarhoven CJHM. Laparoscopic versus open cholecystectomy for patients with symptomatic cholecystolithiasis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;4:CD006231.

Rodgers A, Walker N, Schug S, McKee H, Van Zundert A, Dage D, et al. Reduction of postoperative mortality and morbidity with epidural or spinal anesthesia: results from an overview of randomised trials. BMJ. 2000;321:1493–7.

Lennox PH, Vaghadia H, Henderson C, Martin L, Mitchell GW. Small-dose selective spinal anesthesia for short-duration outpatient laparoscopy: recovery characteristics compared with desflurane anesthesia. Anesth Analg. 2002;94(2):346–50.

Wolf AR, Doyle E, Thomas E. Modifying infants stress responses to major surgery: Spinal vs extradural vs opioid analgesia. Paediatr Anaesth. 1998;8:305–11.

Pursnani KG, Bazza Y, Calleja M, Mughal MM. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy under epidural anesthesia in patients with chronic respiratory disease. Surg Endosc. 1998;12:1082–4.

Hamad MA, Ibrahim El-Khattary OA. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy under spinal anesthesia with nitrous oxide pneumoperitoneum: A feasibility study. Surg Endosc. 2003;17:1426–8.

Tzovaras G, Fafoulakis F, Pratsas K, Georgopouloun S, Stamatiou G, Hatzitheofilou C. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy under spinal anesthesia. A pilot study. Surg Endosc. 2006;20:580–2.

Yuksek YN, Akat AZ, Gozalan U, Daglar G, Yasar Pala Y, Canturk M, et al. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy under spinal anesthesia. Am J Sur. 2008;195:533–6.

Tzovaras G, Fafoulakis F, Pratsas K, Georgopoulou S, Stamatiou G, Hatzitheofilou C. Spinal vs. general anesthesiafor laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Interim analysis of a controlled, randomized trial. Arch Surg. 2008;143:497–501.

Sinha R, Gurwara AK, Gupta SC. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy under spinal anesthesia: A study of 3492 patients. Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2009;19:323–7.

Tiwari S, Chauhan A, Chaterjee P, Alam MT. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy under spinal anaesthesia: A prospective, randomised study. J Min Access Surg. 2013;9:65–71.

Goyal S, Goyal S, Singla S. Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy Under Spinal Anesthesia with Low-Pressure Pneumoperitoneum - Prospective Study of 150 Cases. Arch Clin Exp Surg. 2012;1(4):224–8.

Johnson A. Laparoscopic surgery. Lancet. 1997;349(9052):631–5.

Crabtree JH, Fishman A, Huen IT. Videolaparoscopic peritoneal dialysis catheter implant and rescue procedures under local anesthesia with nitrous oxide pneumoperitoneum. Adv Perit Dial. 1998;14:83–6.

Sharp JR, Pierson WP, Brady CE. Comparison of CO2 and N2O-induced discomfort during peritoneoscopy under local anesthesia. Gastroenterology. 1982;82(3):453–6.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Grp P. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: The PRISMA Statement. Plos Med. 2009;6.

Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, Jenkinson C, Reynolds DJ, Gavaghan DJ, et al. Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials. 1996;17:1–12. doi:10.1016/S0197-2456(96)90740-0. PubMed: 8721797.

Hozo SP, Djulbegovic B, Hozo I. Estimating the mean and variance from the median, range, and the size of a sample. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2005;5:13. doi:10.1186/1471-2288-5-13. PubMed: 15840177.

Kalaivani V, Pujari VS, R SM, Hiremath BV, Bevinaguddaiah Y. Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy: Spinal Anaesthesia vs. General Anaesthesia: A Prospective Randomised Study. J Clin Diagn Res. 2014;8:NC01–4.

Imbelloni LE, Fornasari M, Fialho JC, Sant'Anna R, Cordeiro JA. General Anesthesia versus Spinal Anesthesia for Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy. rev bras anestesiol scientific article. 2010;60(3):217–27.

Ellakany M. Comparative study between general and thoracic spinal anesthesia for laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Egypt J Anaesth. 2013;29:375–81.

Bessa SS, El-Sayes IA, El-Saiedi MK, Abdel-Baki NA, Abdel-Maksoud MM. Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy Under Spinal Versus General Anesthesia: A Prospective, Randomized Study. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech. 2010;20:6.

Turkstani A, Ibraheim O, Khairy G, Alseif A, Khalil N. Arab Board Anesth Spinal versus general anesthesia for laparoscopic cholecystectomy: A comparative study of cost effectiveness and side effects. Pain Intensive Care. 2009;13(1):9.

Mehta PJ, Chavda HR, Wadhwana AP, Porecha MM. Comparative analysis of spinal versus general anesthesia for laparoscopic cholecystectomy: A controlled, prospective, randomized trial. Anesth Essays Res. 2010;4(2):91–5.

Canes D, Desai MM, Aron M, Haber GP, Goel RK, Stein RJ, et al. Transumbilical single-port surgery: evolution and current status. Eur Urol. 2008;54:1020–9. doi:10.1016/j.eururo.2008.07.009. PubMed: 18640774.

Gurusamy KS, Junnarkar S, Farouk M, Davidson BR. Day-case versus overnight stay for laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;16:CD006798. PubMed: 18677781.

Cantore F, Boni L, Di Giuseppe M, Giavarini L, Rovera F, Dionigi G. Pre-incision local infiltration with levobupivacaine reduces pain and analgesic consumption after laparoscopic cholecystectomy: a new device for day-case procedure. Int J Surg. 2008;6:S89–92. doi:10.1016/j.ijsu.2008.12.033. PubMed: 19264565.

Sarli L, Costi R, Sansebastiano G, Trivelli M, Roncoroni L. Prospective randomized trial of low-pressure pneumoperitoneum for reduction of shoulder-tip pain following laparoscopy. Br J Surg. 2000;87:1161–5.

So JB, Cheong KF, Sng C, Cheah WK, Goh P. Ondansetron in the prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc. 2002;16:286–8.

Jensen P, Mikkelsen T, Kehlet H. Postherniorrhaphy urinary retention: effect of local, regional, and general anesthesia: a review. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2002;27:612–7.

Acknowledgements

I am deeply indebted to a number of people without whose encouragement and assistance this thesis would not have been completed.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors do not have any possible conflicts of interest. Gan Yu, Qin Wen, Li Qiu, Li Bo, Jiang Yu.

Authors’ contributions

GY and QW have made substantial contributions to conception and design, or acquisition of data, or analysis and interpretation of data; GY, QW and JY have been involved in drafting the manuscript or revising it critically for important intellectual content; LQ and LB have given final approval of the version to be published; and GY and QW agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Yu, G., Wen, Q., Qiu, L. et al. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy under spinal anaesthesia vs. general anaesthesia: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMC Anesthesiol 15, 176 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12871-015-0158-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12871-015-0158-x