Abstract

Background

This study aims to decipher the genetic basis governing yield components and quality attributes of peanuts, a critical aspect for advancing molecular breeding techniques. Integrating genotype re-sequencing and phenotypic evaluations of seven yield components and two grain quality traits across four distinct environments allowed for the execution of a genome-wide association study (GWAS).

Results

The nine phenotypic traits were all continuous and followed a normal distribution. The broad heritability ranged from 88.09 to 98.08%, and the genotype-environment interaction effects were all significant. There was a highly significant negative correlation between protein content (PC) and oil content (OC). The 10× genome re-sequencing of 199 peanut accessions yielded a total of 631,988 high-quality single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), with 374 significant SNP loci identified in association with the nine traits of interest. Notably, 66 of these pertinent SNPs were detected in multiple environments, and 48 of them were linked to multiple traits of interest. Five loci situated on chromosome 16 (Chr16) exhibited pleiotropic effects on yield traits, accounting for 17.64–32.61% of the observed phenotypic variation. Two loci on Chr08 were found to be strongly associated with protein and oil contents, accounting for 12.86% and 14.06% of their respective phenotypic variations, respectively. Linkage disequilibrium (LD) block analysis of these seven loci unraveled five nonsynonymous variants, leading to the identification of one yield-related candidate gene and two quality-related candidate genes. The correlation between phenotypic variation and SNP loci in these candidate genes was validated by Kompetitive allele-specific PCR (KASP) marker analysis.

Conclusions

Overall, molecular markers were developed for genetic loci associated with yield and quality traits through a GWAS investigation of 199 peanut accessions across four distinct environments. These molecular tools can aid in the development of desirable peanut germplasm with an equilibrium of yield and quality through marker-assisted breeding.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Cultivated peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.) is a significant legume crop that is widely grown in over one hundred countries across Asia, Africa, and North and South America. In 2021, the global peanut planting area was 32.72 million hectares, and the total peanut production amounted to 53.93 million tons [1]. Peanuts are a vital source of edible vegetable oil for human consumption. As living standards improve and consumption habits become more refined, there is an expected increase in demand for premium vegetable oils, including peanut oil. In recent years, breeding new peanut varieties with enhanced yield and improved quality has become the primary strategy for expanding the global peanut business. Unlike the pre-genomic era, peanut breeders today have access to a plethora of innovative technologies for genetic improvement. One of these methods is genome-wide association study (GWAS), which employ linkage disequilibrium (LD) to detect gene loci and their allelic variations in natural populations, linking allelic variations with target traits to analyze gene effects [2]. Since its inception in plants in 2001, GWAS has been used as a major tool for identifying genetic loci associated with traits of interest. In peanuts and other crops, GWAS has effectively identified significant loci controlling major agronomic traits, not least with respect to yield components and quality attributes that have complex genetic underpinnings involving the interaction of multiple alleles and loci that are only partially understood [3,4,5,6,7].

Peanut yield components, such as hundred-pod weight (HPW), hundred-seed weight (HSW), pod number per plant (PN), seed number per plant (SN), pod length (PL), and pod width (PW), are each regulated by their own genetic program while also being intricately related to one another [8]. In recent years, several yield trait QTLs have been reported for peanuts. For example, using SSR (simple sequence repeats) markers, multiple QTL related to several yield components, including HPW, PL, and PW, were identified in a BC2F2:3 population [9], and two major QTLs associated with HPW were identified in a different F2:3 population [10]. Based on a population composed of mutants, 58 markers associated with 39 yield and quality traits were identified using 110 Arachis hypogaea transferable element (AhTE) markers [11]. In several recombination inbred line (RIL) populations, QTLs for HPW and HSW were detected in multiple growth environments [12,13,14]. More recently, with the release of the reference genome of cultivated peanut [15], single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP)-based QTLs related to HSW, SL (seed length), and SW (seed width) were found on chromosomes A02, A05, A06, and B06 [16,17,18,19,20].

Protein and oil, which together account for around 75% of the peanut kernel, are the two primary storage compounds in peanuts [21]. The relative proportion of oil and protein determines the quality of a peanut and varies depending on consumer preference and intended uses. Seven QTLs related to protein content with phenotypic variation explained (PVE) ranging from 1.5 to 10.70% have been reported [22]. Additionally, 78 QTLs associated with oil content were found in two RIL populations [23], and another study identified 20 QTLs related to quality traits on chromosomes A02, A05, A07-A10, B01, B04, and B09 [24]. Yield and quality traits were analyzed in a RIL population using genotyping-by-sequencing, AhTE and SSR markers, and it was found that the QTLs for yield and protein traits were located on A02 and B06, respectively [25]. More recent research efforts have identified an oil content-related QTL (qOCA08.1) in a 0.8 Mb region on chromosome A08 and a crucial QTL (qAh05.1) that influences both oil and protein contents [26, 27]. These findings highlight that the loci impacting yield components cluster on chromosomes A02, A05, A06, A07, B05, and B06, while those governing quality attributes were located on chromosomes A05, A07, A08, A09, B01, B04, B06 and B09. Using diverse population materials to identify new loci is critical for gaining a more nuanced knowledge of the genetic basis of peanut yield and quality attributes.

With the rapid development of sequencing technology, particularly the release of the whole genome sequence of cultivated peanuts [15, 28, 29], a large number of SNPs can be obtained using whole genome scanning technology. This presents a promising opportunity to rapidly explore the genetic basis of yield and quality traits, identify key genes, and incorporate them into peanut breeding programs. Previous research on important peanut traits mainly used artificially constructed segregation populations, GBS (genotyping-by-sequencing), and SNP chips. However, the results of such research on peanut yield and quality traits varied, and most of the candidate genes were not identified or investigated. GWAS, in contrast, can identify more allele variations by leveraging natural populations, abrogating the time-consuming and labor-intensive process of population construction. Significant locus verification and GWAS analysis using re-sequencing data are still in their early stages.

This study employed GWAS by utilizing 199 accessions, comprising both released varieties and advanced breeding lines derived from the Kainong breeding program, alongside re-sequencing and phenotypic data gathered over three years in four distinct environments. The results not only shed more light on the genetic basis of yield and quality traits but also offer valuable insights for cloning and characterizing the underlying genes as well as developing molecular markers. These markers can facilitate the molecular breeding and genetic engineering of novel peanut germplasm with enhanced yield potential and desirable quality traits.

Materials and methods

Plant materials and growth conditions

A total of 199 Chinese peanut germplasm accessions were collected from various sites across China, including the Kaifeng Academy of Agricultural and Forestry Sciences in Henan province, the Hebei Academy of Agriculture and Forestry Sciences, and the Institute of Oil Crops at the Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences in Hubei province. Some accessions have been registered by the state, while others are advanced breeding lines (Fig. S1; Dataset S1). The selected 199 lines were cultivated over three consecutive years (2019, 2020, and 2021) at experimental fields in Kaifeng (114°27′E, 34°77′N) and Xinyang (114°07′E, 32°12′N) in Henan province, China. Four experimental environments were designated as E1 (Kaifeng in 2019), E2 (Xinyang in 2019), E3 (Kaifeng in 2020), and E4 (Kaifeng in 2021). A randomized block design with three replicates was employed, planting 165 seeds of each material in a 6.67 × 2 m2 plot [30]. Each row contained 33 plants per accession, with a 40 cm spacing between rows and a 20 cm spacing between individual plants. The experimental field featured medium soil fertility, good drainage and irrigation, level topography, and sandy loam. After harvesting, seven yield components, HPW, HSW, SP, NP (total number of 500 g of pods), NS (total number of 250 g of seeds), PL, and PW, were measured according to the standard procedures [31]. Quality traits, including protein content (PC) and oil content (OC), were determined using near-infrared reflectance spectroscopy (DA7250; Perten Instruments, Beijing, China).

DNA extraction and genotype sequencing

Genomic DNA was extracted from approximately 100 mg of unfolded leaves collected from 3-week-old seedlings using a plant genomic DNA kit (Tiangen, Beijing, China). DNA integrity, quality, and concentration were assessed through gel electrophoresis, NanoDrop™2000 (Thermo Fisher, Waltham, MA), and a Qubit fluorometer (Thermo Fisher). Qualified DNA samples were randomly fragmented with a Covaris® ultrasonic breaker (Covaris, Woburn, MA) before library construction. The process included end-repairing and phosphorylation, A-tailing, index adapter ligation, denaturation, and PCR amplification. The constructed library was sequentially sequenced on an Illumina HiSeqTM2000 platform (Illumina, San Diego, CA) by Novogene (Beijing, China).

Analysis of phenotypic data

Phenotypic statistical analyses were conducted using mixed linear models in Genstat version 22.0 [32] using Kainong 69 as a control. Phenotype summary statistics and correlation analysis were performed using DPS v20.0 and the performance analytics package of the R language [33]. The variance component was analyzed by calculating the generalized heritability of phenotypes using restricted maximum likelihood (REML) and the following formula: h2 = σ2g/(σ2g + σ2ge/n + σ2ε /nr), where σ2g represents the genotypic variance, σ2ge represents the interaction between 199 genotypes and the environment; σ2ε represents the residual variance component; n is the number of environment trials; and r is the number of replicates in each environment trial [34].

SNP alignment and calling

Paired-end re-sequencing reads were mapped to the reference genome of A. hypogaea Kaixuan 016 (in preparation for publication) using the Burrows-Wheeler Aligner software version 0.7.8 [35]. After sorting, potential PCR duplicates were removed by ‘rmdup’. When multiple read pairs with identical external coordinates were found, only the pair with the highest mapping quality was retained [36]. Following alignment, population-scale SNP calling was performed using SAMtools [35]. To abate SNP calling errors caused by incorrect mapping or insertions and deletions (InDels), only high-quality SNPs (coverage depth ≥ 3, RMS mapping quality ≥ 20, maf ≥ 0.05, miss ≤ 0.2) were used for subsequent analysis. The density of SNP loci was statistically analyzed using the R language.

Linkage disequilibrium and population genetic structure

LD decay analysis was conducted using PopLDdecay software [37]. Population structure was analyzed using Admixture 1.23 software [38]. To clarify the phylogenetic relationship from a genome-wide perspective, an individual-based neighbor-joining (NJ) tree was constructed based on the p-distance using TreeBest 1.9.2 software (http://treesoft.sourceforge.net/treebest.shtml) and visualized using MEGA6.0 [39]. Genetic structure was evaluated by PCA using GCTA 1.24.2 software [40], and the significance level of the eigenvectors was determined using the Tracey-Widom test [41]. Heatmaps were drawn using kinship analysis in the TASSEL software package [42].

Genome-wide association analysis and candidate gene discovery

GWAS was conducted using GEMMA (genome-wide efficient mixed-model association) version 0.94.1 [43, 44]. The mixed linear model (MLM) analysis was performed using the following equation:

y = Xα + Sβ + Kµ + e.

In this equation, y corresponds to phenotype; X corresponds to genotype; S represents the structure matrix, and K represents the relative kinship matrix. Xα and Sβ represent fixed effects, while Kµ and e represent random effects. The top three principal components were used to construct the S matrix for population structure correction. The matrix of simple matching coefficients was used to build the K matrix. Annotation was performed using the ANOVAR package against the reference genome, Kaixuan 016.

High-quality SNPs were categorized based on the primary gene structure, including exonic regions, intronic regions, splicing sites, upstream and downstream regions, and intergenic regions. SNPs in coding exons were further dichotomized into those with synonymous mutations and those with nonsynonymous mutations, including those causing stop codons. PVE was analyzed using the Lm and ANOVA packages in the R language. Block analysis was conducted using the LDBlockShow 1.40 software [45]. The map of significant loci was drawn using the VennDiagram and UpSetR packages of the R language [46, 47]. Boxplots were drawn by R software. The significance of variation was evaluated using the t-test. KASP primers were synthesized by Golden Maker Technology (Beijing, China).

Results

Phenotypic diversity and heritability

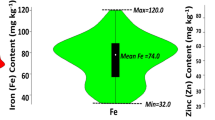

The phenotypic observations of the nine traits under study were all continuous and followed a normal distribution. The mean values of the measured phenotypic traits, including HPW, HSW, SP, NP, NS, PL, PW, PC, and OC across four growth environments (Kaifeng in 2019, Xinyang in 2019, Kaifeng in 2020, Kaifeng in 2021) were 201.54 g, 73.07 g, 65.14%, 341.25, 449.22, 37.67 cm, 16.03 cm, 24.26%, and 50.05%, respectively (Table 1). The highest coefficients of variation (CV) were observed in NP and HPW, at 21.15% and 20.90%, respectively, while OC had the lowest CV at 3.97%. These results suggest that the environment had a greater impact on the phenotypes of NP and HPW than on those of OC. The broad-sense heritability (h2) of all nine traits ranged from 88.09 to 98.08%, indicating that the phenotypes of these traits were primarily determined by genetic factors (Table 1). Analysis of variance for nine traits indicated that the effect of genotypes, environments, and GE interactions were all significant (Table S1).

Among the seven traits of yield components, significant positive correlations were observed among HPW, HSW, PL, and PW, while significant negative correlations were found among SP, NP, and NS (Fig. 1). The highest positive correlation was between HPW and HSW, with a r value of 0.83, while the highest negative correlations were observed between HPW and NP, as well as between HSW and NS, both with a r value of -0.86. Regarding the quality traits, PC and OC exhibited a negative correlation, with a r value of -0.86. Except SP, NP, and NS, all other yield component traits exhibited negative correlations with PC and OC.

Correlation coefficient of the nine traits. HPW, hundred-pod weight; HSW, hundred-seed weight; SP, shelling percentage; NP, the total number of 500 g of pods; NS, the total number of 250 g of seeds; PL, pod length; PW, pod width. PC, protein content; OC, oil content. The number represents the correlation coefficient (r) value between traits. The circles in the lower half corner are distributed around the lines. r is high when the circles are located near the line. The greater the correlation between the traits, the larger the number in the upper left corner. ***, significant at p < 0.1% level, **, significant at p < 1% level, *, significant at p < 5% level

Genomic variations of SNPs

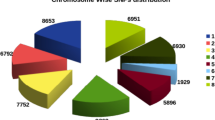

The re-sequencing of all 199 peanut accessions with a sequencing depth of 10x generated a total of 7,056,911 Gb of raw data, with an average of 35,640,964 Mb of raw data per sample. The total amount of filtered, clean data was 7,048,906 Gb, with an average of 35,600,534 Mb per sample. After SNP calling and filtering, a total of 631,988 SNPs were retained. The highest number of SNPs was observed on Chr03, with 48,821, followed by Chr11 with 43,292 SNPs. In contrast, the lowest number of SNPs was found on Chr08, with 13,143 SNPs, followed by Chr10 with 13,848 SNPs. The average SNP density on chromosomes was 251.71/M (Fig. 2).

Functional annotation analysis revealed that 89.54% of the SNPs were situated in intergenic regions, with the remaining 10.46% identified within genic regions. Within these genic regions, a cumulative total of 26,899 SNPs were discernible in introns, subsequently followed by untranslated regions (UTRs) and coding regions of the annotated genes.

Linkage disequilibrium decay

The LD decay was estimated by determining the LD coefficient (r2) between pairwise SNPs. Utilizing the parameters ‘-n -dprime-minMAF 0.05’ in PopLDdecay, the average r2 value was computed for pairwise markers within a 500 kb window and averaged across the entire genome. Following the suggestion of a previous study [48], the LD decay distance was defined as half of the maximum r2 value. Consequently, the peanut population’s LD was estimated to be 115 kb when r2 equaled 0.15 (Fig. S2).

Population structure analysis

To understand the genetic structure of the population, 199 peanut accessions were categorized based on SNP data, and the class distribution of k values from 1 to 8 was calculated and simulated according to the Bayesian algorithm (Fig. 3A). When k equals five, the population can be segmented into five distinct groups. As shown in Fig. 3B, Group I (GI) comprised 23 accessions, all of which were multi-kernel types, resembling their paternal parent, Kainong 15. GroupII (GII) contained 14 accessions with PL to PW ratios less than 1.8. Group III (GIII) included 12 accessions, 75% of which exhibited a PL to PW ratio exceeding 2.7. Group IV (GIV) was consisted of seven varieties, six of them were derived from the same maternal parent. Group V (GV) was the largest category encompassing 143 accessions, all derived from advanced lines chosen during high-yield breeding (Fig. 3B; Dataset S1). PCA analysis based on the first (PC1) and the second (PC2) principal components revealed that, except for the first category, no distinct classification boundaries were evident (Fig. 3C). Similarly, the heat map generated using the k-matrix also displayed promiscuous boundaries between the five groups (Fig. 3D).

Genome-wide association studies

In the association panel comprising 199 peanut accessions, a total of 631,988 SNPs (minor allele frequency ≥ 0.05; missing rate ≤ 0.2; depth ≥ 3) were used for the GWAS analysis. The threshold value of GWAS, determined by the Bonferroni test, was 7.10 [- log10 (0.05/631,988)]. A total of 95, 161, 99, and 101 maker traits associations (MATs) were identified in the environments E1, E2, E3, and E4, respectively (Fig. 4A; Table S2). The number of SNPs detected for individual traits varied across different environments. In E3, the maximum number of SNPs detected for HPW and SP was 7 and 14, respectively. In E2, the maximum number of SNPs detected for HSW, NP, PL, and PC was 11, 17, 17, and 39, respectively. The highest numbers of SNPs for NS and PW were detected in E4 and E1, respectively. No SNP was discernible for HPW and HSW in E4, nor for SP in E2. A total of 12, 14, 18, 37, 84, 23, 32, 82, and 72 non-redundant association sites were identified for HPW, HSW, SP, NP, NS, PL, PW, PC, and OC, respectively (Fig. 4B; Table S2). The associated loci of yield components were primarily situated on Chr08 and Chr16, with a lesser extent on Chr13, while those of the two quality traits were predominantly located on Chr08 and Chr18. The Manhattan plots and quantile-quantile plots of each trait under the four environments are shown in Fig. S3.

A total of 374 significant loci were detected for the nine traits, with 66 of these detected in more than two environments. For example, Arahy.16_142867474 for PL and Arahy.16_142692237 for PW were detected in all four environments (Fig. 4A). Forty-eight SNP loci were attributable to two or more traits. For instance, Arahy.16_142692237, Arahy.16_139632313, Arahy.16_142656321, and Arahy.16_138643609 were associated with six, five, four, and three yield components, respectively. The repeatedly detected loci for quality traits were all located on Chr08, while those related to yield traits were primarily found on Chr16. Apart from SP, no SNP overlap was observed between quality traits and yield traits (Fig. 4B; Table S3).

The profile of the associated loci for the selected nine traits of the 199 accessions across four different environments. A: The Venn diagram depicting the associated loci for the nine traits under four environments. B: The statistical column diagram representing the associations of the nine traits and their interactive upset plot. E1, Kaifeng in 2019; E2, Xinyang in 2019; E3, Kaifeng in 2020; E4, Kaifeng in 2021; HPW, hundred-pod weight; HSW, hundred-seed weight; SP, shelling percentage; NP, the total number of 500 g of pods; NS, the total number of 250 g of seeds; PL, pod length; PW, pod width

Verification of the relationship between SNPs and phenotype

To verify the associated loci of the selected seven yield traits and two quality traits in peanuts, we extracted the genotypes of seven SNP loci from 199 accessions and chose approximately 50 extreme phenotypes for each trait to construct box plots using the following criteria: HPW ≥ 220 g, HPW ≤ 160 g, HSW ≥ 80 g, HSW ≤ 65 g, SP ≥ 69%, SP ≤ 62%; NP ≥ 380, NP ≤ 290, NS ≥ 500, NS ≤ 390, PL ≥ 41 cm, PL ≤ 34 cm, PW ≥ 17 cm, PW ≤ 15 cm, PC ≥ 25%, PC ≤ 23.6%, OC ≥ 50%, OC ≤ 49%. Significant phenotypic differences between the two base types for the nine traits were evident (Dataset S2). At the Arahy16_138643609 site, the high-yield genotypes had a CC base, in contrast to TT in the low yield genotypes. For Arahy.16_139632313 and Arahy.16_142692237, the high-yield genotypes had a GG base, while the low-yield genotypes had an AA base. In Arahy.16_142656321, the high-yield genotypes featured a TT base, as opposed to CC in the low-yield genotypes. In Arahy.16_142867474, the high-yield genotypes had a GG base, while the low-yield genotypes had a CC base. At Arahy.08_38378278, the high-oil and low-oil genotypes had TT and CC bases, respectively. In Arahy.08_49538603, the high-PC/low-OC genotypes had an AA base, in contrast to CC in the low-PC/high-OC genotypes (Fig. S4). The genotype proportion of CC/TT, GG/AA, GG/AA, TT/CC, GG/CC, TT/CC and CC/AA were 168/25, 150/27, 158/28, 156/27, 157/33, 116/41 and 136/45, respectively (Dataset S2).

Candidate genomic regions for yield and quality traits

Yield trait loci were predominantly clustered on Chr16, where SNP Arahy.16_138643609, Arahy.16_42656321, and Arahy.16_142867474 were repeatedly identified in association with four yield traits across multiple environments. Additionally, SNP Arahy.16_139632313 and Arahy.16_142692237 were associated with five and six yield traits, respectively, in multiple environments. The highest PVE of yield component trait loci in different environments ranged from 17.64 to 32.61% (Table 2). Arahy.16_139632313, which was closely related to five yield traits, accounting for 26.43% of the phenotypic variation of HPW in E1. Arahy.16_142692237 and Arahy.16_142867474 were consistently found in association with PL and PW in all four environments. Arahy.16_142692237 and Arahy.16_142867474 accounted for 17.64% and 21.17% of the phenotypic variations in E3 and E2, respectively. In contrast, Arahy.08_38378278 and Arahy.08_49538603 were linked with quality traits, accounting for 12.86% and 14.06% of the phenotypic variation of OC in E1 and E3, respectively. Analysis of the 115 kb region upstream and downstream of these sites using the LD haplotype block diagram revealed that the seven significant SNP sites formed seven blocks, including a total of 158 SNPs (Fig. 5). Among these seven blocks, the peak value (- log10P) of yield traits ranged from 7.11 to 10.48 in different environments, and the peak value of quality traits ranged from 5.06 to 7.06 (Table S4).

LD block surrounding the significant SNPs. The pairwise Linkage Disequilibrium (LD) between the SNP markers is indicated as D’ values, where red indicates a value of 1 and yellow indicates 0. Dark red represents the highest correlation and the highest LD between the two SNPs. D’ is the standardized linkage disequilibrium coefficient

Using Kaixuan 016 as the reference genome, we discovered that five SNPs located in the coding regions of several key genes resulted in nonsynonymous variations (Table 3). Gene function annotation analysis revealed that one of the SNPs, Arahy.16_142682809, was situated within the coding region of gene evm.TU.ctg197.486, which encodes a pyruvate monooxygenase. This SNP led to an amino acid substitution of Lys to Asn in the fourth exon, resulting from a nucleotide substitution of A to C. Another SNP, Arahy.16_142783542, was identified in the coding region of evm.TU.ctg197.494, which encodes a shikimate_O-hydroxycinnamoyltransferase. The SNP caused an amino acid alteration from Arg to Lys. Moreover, the Arahy.08_38352339 SNP was discovered in the second exon of evm.TU.ctg335.1373, encoding an NAC transcription factor. A nucleotide change from C to A led to the formation of a stop codon. The Arahy.08_38476979 SNP was found in the third exon of evm.TU.ctg335.1377, encoding an NAC domain-containing protein. A nucleotide alteration from A to G resulted in an amino acid substitution from Ile to Val. Finally, the Arahy.08_49440731 SNP was located in the first exon of evm.TU.ctg335.2426, which encodes a protein predicted to be involved in carbohydrate metabolism. This SNP caused a Thr-to-Ile amino acid substitution due to a C-to-T nucleotide alteration.

KASP markers validation of the SNPs

The association between the five aforementioned SNPs and peanut yield components and quality traits was validated by analyzing re-sequencing data and evaluating the phenotypic performance of the population. At the Arahy16_142682809 site, the GG genotype was associated with high yield, whereas the TT genotype was linked to low yield. Similarly, the high-oil trait was associated with the GG genotype at the Arahy.08_38352339 site. For the Arahy.08_49440731 site, the GG genotype was associated with high-PC/low-OC, while the low-PC/high-OC feature was associated with the AA genotype (Fig. S5). However, no variation was observed among the population at the Arahy.16_142783542 site and the SNP in Arahy.08_38476979 did not lead to any significant phenotypic variation.

Subsequently, KASP markers were designed for Arahy.16_142682809, Arahy.08_38352339, and Arahy.08_49440731 and validated in a total of 199 peanut accessions (Table S5, Fig. 6). The results, illustrated in Figs. 7 and 8, and 9, demonstrated that these KASP markers can effectively differentiate the SNPs at Arahy.16_142682809, Arahy.08_38352339, and Arahy.08_49440731 with clarity and precision.

Kompetitive allele-specific PCR (KASP) validation of the phenotypic variations between two base types at Arahy.16_142682809. E1, Kaifeng in 2019; E2, Xinyang in 2019; E3, Kaifeng in 2020; E4, Kaifeng in 2021; HPW, hundred-pod weight; HSW, hundred-seed weight; SP, shelling percentage; NP, total number of 500 g of pods; NS, total number of 250 g of seeds; PL, pod length; PW, pod width

Discussion

Peanut yield and quality are crucial for the thriving peanut industry, as they directly impact its economic value and global competitiveness. GWAS has emerged as a powerful tool for identifying key genes that influence these essential traits. By unraveling the genetic architecture of high-yield and superior-quality peanuts, GWAS enables the development of marker-assisted breeding programs. This targeted approach accelerates the breeding process, ensuring the cultivation of high-performing peanut varieties that cater to consumer demand and market needs. In turn, this advances the industry’s sustainability and profitability, benefiting both producers and consumers alike.

This study analyzed 199 peanut accessions, all originating from the high-oleic acid-containing Chinese variety Kaixuan 016 [49, 50]. Genotyping analysis of this diverse population, featuring significant variation in yield components and quality parameters, was enabled by using Kaixuan 016 as a reference genome. The presence of a normal distribution of phenotypic data (Fig. 1), coupled with pedigree analysis and the genetic contribution of Kaixuan 016 to derived lines (as per unpublished data), indicated a rich genetic diversity among the 199 accessions.

The substantial phenotypic diversity displayed across four distinct growth environments enhances genotyping efficiency and improves the resolution of GWAS analyses. By monitoring the population for LD decay, we made accurate estimates regarding the required number and granularity of markers for meaningful association analysis [51,52,53]. Given Kaixuan 016’s reference genome size of 2.53 Gb, we estimated that 22,528 SNP markers (genome size/LD attenuation distance) would be necessary for accurate association analysis. However, 631,988 SNPs were identified in this study, representing the most abundant high-quality SNP loci obtained via the 10× deep sequencing of peanuts to date, far exceeding the number used in prior studies [17, 54, 55].

It was observed that the CV values for yield traits were higher than those for quality traits across all four environments, aligning with other studies that found yield traits to be more susceptible to environmental influence [56, 57]. Broad-sense heritability for all nine traits exceeded 80%, indicating that phenotypes were primarily determined by genotype [58]. A quantitative trait like yield can have a high heritability as the experiment was well conducted with high appropriate replication levels, and this higher heritability had also been observed in other studies [59, 60]. Among yield traits, HPW, HSW, PL, and PW were positively correlated with one another, while SP displayed a significant negative correlation. Larger pods were associated with less plump kernels, likely due to homeostatic compensatory effects influencing plant growth and development. Furthermore, a negative correlation was observed between PC and OC, consistent with the competitive metabolism and accumulation of oil and proteins as major storage compounds in peanut seeds [27].

Investigating a population’s genetic structure can clarify its origin, composition, and evolution, while controlling false positives produced by population structure through PCA and structural analysis. The 199 accessions were categorized into five groups in this study. Kainong 15, the paternal parent of all 23 accessions in GI, is a red testa variety with 3–4 kernels per pod. The heritability of multi-kernel pods was strong, with all progenies derived from Kainong 15 being multi-kernelled. Peanut populations GII, GIII, and GV represent small, large, and medium-sized pods, respectively. This variation in pod size between groups enables the easier identification of significant linkage loci for economic traits through association analysis.

In this study, GWAS analysis identified 374 significant SNP loci associated with nine traits, including 220 for yield traits and 154 for quality traits (Fig. 4B; Table S2). The number of associated loci identified substantially exceeded those reported in previous studies [10, 11, 17, 25, 57, 61]. We pinpointed several candidate genes, such as those encoding pyruvate monooxygenase, shikimate_O-hydroxycinnamoyltransferase, and the NAC transcription factor, which are potentially associated with yield component and quality traits. Pyruvate monooxygenases catalyze the conversion of pyruvate to acetyl-CoA, a central molecule in cellular metabolism, including the citric acid cycle and fatty acid biosynthesis [62]. Shikimate_O-hydroxycinnamoyltransferase is involved in the phenylpropeanoid biosynthesis pathway and plays a crucial role in synthesizing various secondary metabolites such as lignins, flavonoids, and phenolic acids [63]. These compounds contribute to the seed coat’s structure and integrity, which are vital for protecting the developing embryos and maintaining seed viability. Although not directly associated with seed storage compound accumulation, its involvement in the phenylpropanoid pathway can have indirect effects on these processes [64, 65].

NAC transcription factors are plant-specific proteins with essential regulatory roles in plant development and stress responses. In peanut kernel development, NAC transcription factors may regulate gene expression related to cell differentiation, expansion, and maturation, as well as the response to environmental stress factors impacting flower and kernel development [66]. Overexpression of OsNAC6 in rice leaded to growth hindrance and yield reduction [67]. Additionally, grape NAC26 polymorphism had been linked to fruit size variations [68]. Given that these genes may play a role in providing the necessary energy and precursors for the synthesis of lipids, proteins, and other biomolecules during seed development, it is plausible to assume that the SNPs present in these genes may affect their function and impact peanut kernel yield or quality in one way or another. Three candidate genes associated with peanut yield and quality traits, specifically evm.TU.ctg197.486, evm.TU.ctg335.1373, and evm.TU.ctg335.2426 were identified to be arahy.6PM354, arahy.65HUV4, and arahy.QNIR3T respectively in Tifrunner genome (https://www.peanutbase.org/peanut_genome). Among them, the oil content candidate gene arahy.65HUV4 was reported in the previous study [69]. A BLAST search within NCBI (National Center for Biotechnology Information) databases revealed that the other two genes were not reported.

Three KASP markers were developed for SNPs at Arahy.16_142682809 (yield component traits) and Arahy.08_38352339 and Arahy.08_49440731 (quality traits). The effectiveness of these markers was verified, suggesting their potential as selection markers for yield and quality traits. These markers could prove valuable for the fine mapping of candidate genes and can be directly applied in peanut breeding programs to enable accurate and effective selection of desired traits. However, further research is necessary to validate the function of these SNPs and comprehend the underlying biological mechanisms involved. Acquiring this knowledge is crucial for optimizing the accuracy and efficiency of marker-assisted breeding as well as recognizing any limitations or constraints that may arise when implementing these markers in breeding programs.

Data availability

The re-sequencing datasets of the 199 peanut materials have been deposited in the NCBI Sequence Read Archive (SRA) under accession PRJNA974180 (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sra/PRJNA974180).

Abbreviations

- GWAS:

-

Genome-wide association study

- SNP:

-

Single nucleotide polymorphism

- LD:

-

Linkage disequilibrium

- KASP:

-

Kompetitive allele-specific PCR

- InDels:

-

Insertions and deletions

- NJ:

-

Neighbor-joining

- UTR:

-

Untranslated region

- CV:

-

Correlation of variation

- HPW:

-

Hundred-pod weight

- HSW:

-

Hundred-seed weight

- SP:

-

Shelling percentage

- NP:

-

Total number of 500 g of pods

- NS:

-

Total number of 250 g of seeds

- PL:

-

Pod length

- PW:

-

Pod width

- PC:

-

Protein content

- OC:

-

Oil content

References

FAO Statistical database. Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 2023; https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QCL.

Mackay I, Powell W. Methods for linkage disequilibrium mapping in crops. Trends Plant Sci. 2007;12:57–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tplants.2006.12.001.

Huang XH, Wei XH, Sang T, Zhao Q, Feng Q, Zhao Y, Li CY, Zhu CR, Lu TT, Zhang ZW, Li M, Fan DL, Guo YL, Wang AH, Wang L, Deng LW, Li WJ, Lu YQ, Weng QJ, Liu KY, Huang T, Zhou TY, Jing YF, Li W, Lin Z, Buckler ES, Qian Q, Zhang QF, Li JY, Han B. Genome-wide association studies of 14 agronomic traits in rice landraces. Nat Genet. 2010;42:961–7. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.695.

Pandey MK, Monyo E, Ozias-Akins P, Liang X, Guimarães P, Nigam SN, Upadhyaya HD, Janila P, Zhang X, Guo B, Cook DR, Bertioli DJ, Michelmore R, Varshney RK. Advances in Arachis genomics for peanut improvement. Biotechnol Adv. 2012;30:639–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biotechadv.2011.11.001.

Babu BK, Mathur RK, Ravichandran G, Anita P, Venu MVB. Genome wide association study (GWAS) and identification of candidate genes for yield and oil yield related traits in oil palm (Eleaeis guineensis) using SNPs by genotyping-based sequencing. Genomics. 2020;112:1011–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygeno.2019.06.018.

Chidzanga C, Mullan D, Roy S, Baumann U, Garcia M. Nested association mapping-based GWAS for grain yield and related traits in wheat grown under diverse Australian environments. Theor Appl Genet. 2020;135:4437–56. https://doi.org/10.1007/S00122-022-04230-9.

Abdel-Haleem H, Luo ZN, Szczepanek A. Genetic diversity and population structure of the USDA collection of Brassica juncea L. Ind. Crop Prod. 2022;187:115379. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indcrop.2022.115379.

Gomes RLF, Lopes RCDA. Correlations and path analysis in peanut. Crop Breed Appl Biotechnol. 2005;5:105–12. https://doi.org/10.12702/1984-7033.v05n01a14.

Fonceka D, Tossim HA, Rivallan R, Vignes H, Raye I, Ndoye O, Moretzsohn MC, Bertioli DJ, Glazmann JC, Courtois B, Rami JF. Fostered and left behind alleles in peanut: interspecific QTL mapping reveals footprints of domestication and useful natural variation for breeding. BMC Plant Biol. 2012;12:26. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2229-12-26.

Huang L, He H, Chen W, Ren X, Chen Y, Zhou X, Xia Y, Wang X, Jiang X, Liao B, Jiang H. Quantitative trait locus analysis of agronomic and quality-related traits in cultivated peanut (Arachis hypogaea L). Theor Appl Genet. 2015;128:1103–15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00122-015-2493-1.

Hake AA, Shirasawa K, Yadawad A, Nayak SN, Mondal S, Badigannavar AM, Nadaf HL, Gowda MVC, Bhat RS. Identification of transposable element markers associated with yield and quality traits from an association panel of independent mutants in peanut (Arachis hypogaea L). Euphytica. 2017;213:283. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10681-017-2070-6.

Chen W, Jiao Y, Cheng L, Huang L, Liao B, Tang M, Ren X, Zhou X, Chen Y, Jiang H. Quantitative trait locus analysis for pod- and kernel-related traits in the cultivated peanut (Arachis hypogaea L). BMC Genet. 2016;17:25. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12863-016-0337-x.

Luo H, Guo J, Ren X, Chen W, Huang L, Zhou X, Che Y, Liu N, Xiong F, Lei Y, Liao B, Jiang H. Chromosomes A07 and A05 associated with stable and major QTLs for pod weight and size in cultivated peanut (Arachis hypogaea L). Theor Appl Genet. 2018;131:267–82. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00122-017-3000-7.

Wang Z, Huai D, Zhang Z, Cheng K, Kang Y, Wan L, et al. Development of a high-density genetic map based on specific length amplified fragment sequencing and its application in quantitative trait loci analysis for yield-related traits in cultivated peanut. Front Plant Sci. 2018;9:827. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2018.00827.

Bertioli DJ, Jenkins J, Clevenger J, Gao D, Seijo G, Leal-Bertioli SC, Ren L, Farmer AD, Pandey MK, Samoluk SS, Abernathy B, Agarwal G, Ballén-Taborda C, Cameron C, Campbell J, Chavarro C, Chitikineni A, Chu Y, Dash S, El Baidouri M, Guo B, Huang W, Kim KD, Korani W, Lanciano S, Lui CG, Mirouze M, Moretzsohn MC, Pham M, Shin JH, Shirasawa K, Sinharoy S, Sreedasyam A, Weeks NT, Zhang X, Zheng Z, Sun Z, Froenicke L, Aiden EL, Michelmore R, Varshney RK, Holbrook CC, Cannon EKS, Scheffler BE, Grimwood J, Ozias-Akins P, Cannon SB, Jackson SA, Schmutz J. The genome sequence of segmental allotetraploid peanut Arachis hypogaea. Nat Genet. 2019;51:877–84. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41588-019-0405-z.

Zhang S, Hu X, Miao H, Chu Y, Cui F, Yang W, et al. QTL identification for seed weight and size based on a high-density SLAF-seq genetic map in peanut (Arachis hypogaea L). BMC Plant Biol. 2019;19:537. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-019-2164-5.

Zhou X, Guo J, Pandey MK, Varshney RK, Huang L, Luo H, Liu N, Chen W, Lei Y, Liao B, Jiang H. Dissection of the genetic basis of yield-related traits in the Chinese peanut mini-core collection through genome-wide association studies. Front Plant Sci. 2021;12. https://doi.org/10.3389/FPLS.2021.637284.

Gangurde SS, Wang H, Yaduru S, Pandey MK, Fountain JC, Chu Y, Isleib T, Holbrook CC, Xavier A, Culbreath AK, Ozias-Akins P, Varshney RK, Guo B. Nested-association mapping (NAM)-based genetic dissection uncovers candidate genes for seed and pod weights in peanut (Arachis hypogaea). Plant Biotech J. 2020;18:1457–71. https://doi.org/10.1111/pbi.13311.

Wang J, Yan C, Li Y, Li C, Zhao X, Yuan C, Sun Q, Shan S. GWAS Discovery of candidate genes for yield-related traits in peanut and support from earlier QTL mapping studies. Genes (Basel). 2019;10:803. https://doi.org/10.3390/genes10100803.

Zhao H, Tian R, Xia H, Li C, Li G, Li A, Zhang X, Zhou X, Ma J, Huang H, Zhang K, Thudi M, Ma C, Wang X, Zhao C. High-density genetic variation map reveals key candidate loci and genes associated with important agronomic traits in peanut. Front Genet. 2022;13:845602. https://doi.org/10.3389/fgene.2022.845602.

Wang M, Chen CY, Tonnis B, Pinnow D, Davis J, An YC, et al. Changes of seed weight, fatty acid composition, and oil and protein contents from different peanut FAD2 genotypes at different seed developmental and maturation stages. J Agric Food Chem. 2018;66:3658–65. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jafc.8b01238.

Sarvamangala C, Gowda MVC, Varshney RK. Identification of quantitative trait loci for protein content, oil content and oil quality for groundnut (Arachis hypogaea L). Field Crops Res. 2011;122:49–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fcr.2011.02.010.

Pandey MK, Wang M, Qiao L, Feng S, Khera P, Wang H, Tonnis B, Barkley NA, Wang J, Holbrook CC, Culbreath AK, Varshney RK, Guo B. Identification of QTL associated with oil content and mapping FAD2 genes and their relative contribution to oil quality in peanut (Arachis hypogaea L). BMC Genet. 2014;15:133. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12863-014-0133-4.

Shasidhar Y, Vishwakarma MK, Pandey MK, Janila P, Variath MT, Manohar SS, Nigam SN, Guo B, Varshney RK. Molecular mapping of oil content and fatty acids using dense genetic maps in groundnut (Arachis hypogaea L.). Front. Plant Sci. 2017;8:794. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2017.00794.

Jadhav MP, Gangurde SS, Hake AA, Yadawad A, Mahadevaiah SS, Pattanashetti SK, Channabyre Gowda MV, Shirasawa K, Varshney RK, Pandey MK, Bhat RS. Genotyping-by-sequencing based genetic mapping identified major and consistent genomic regions for productivity and quality traits in peanut. Front Plant Sci. 2021;122034. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2021.668020.

Liu N, Guo J, Zhou X, Wu B, Huang L, Luo H, Chen Y, Chen W, Lei Y, Huang Y, Liao B, Jiang H. High-resolution mapping of a major and consensus quantitative trait locus for oil content to a ∼ 0.8-Mb region on chromosome A08 in peanut (Arachis hypogaea L). Theor Appl Genet. 2020;133:37–49. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00122-019-03438-6.

Sun Z, Qi F, Liu H, Qin L, Xu J, Shi L, Zhang Z, Miao L, Huang B, Dong W, Wang X, Tian M, Feng J, Zhao R, Zheng Z, Zhang X. QTL mapping of quality traits in peanut using whole-genome resequencing. Crop J. 2022;10:177–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cj.2021.04.008.

Chen X, Lu Q, Liu H, Zhang J, Hong Y, Lan H, Li H, Wang J, Liu H, Li S, Pandey MK, Zhang Z, Zhou G, Yu J, Zhang G, Yuan J, Li X, Wen S, Meng F, Yu S, Wang X, Siddique KHM, Liu ZJ, Paterson AH, Varshney RV, Liang X. Sequencing of cultivated peanut, Arachis hypogaea, yields insights into genome evolution and oil improvement. Mol Plant. 2019;12:920–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molp.2019.03.005.

Zhuang W, Chen H, Yang M, Wang J, Pandey MK, Zhang C, Chang WC, Zhang L, Zhang X, Tang R, Garg V, Wang X, Tang H, Chow CN, Wang J, Deng Y, Wang D, Khan AW, Yang Q, Cai T, Bajaj P, Wu K, Guo B, Zhang X, Li J, Liang F, Hu J, Liao B, Liu S, Chitikineni A, Yan H, Zheng Y, Shan S, Liu Q, Xie D, Wang Z, Khan SA, Ali N, Zhao C, Li X, Luo Z, Zhang S, Zhuang R, Peng Z, Wang S, Mamadou G, Zhuang Y, Zhao Z, Yu W, Xiong F, Quan W, Yuan M, Li Y, Zou H, Xia H, Zha L, Fan J, Yu J, Xie W, Yuan J, Chen K, Zhao S, Chu W, Chen Y, Sun P, Meng F, Zhuo T, Zhao Y, Li C, He G, Zhao Y, Wang C, Kavikishor PB, Pan RL, Paterson AH, Wang X, Ming R, Varshney RK. The genome of cultivated peanut provides insight into legume karyotypes, polyploid evolution and crop domestication. Nat Genet. 2019;51:865–76. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41588-019-0402-2.

Gai J. Statistical methods for experiment. Beijing: China Agricultural; 2000. pp. 23–4.

Liu H, Ren Y, Xu Z. DUS testing principle and technology of new peanut varieties. Guangzhou: South China University of Technology; 2012. pp. 30–8.

VSN International. Genstat for Windows 22nd Edition. Hemel Hempstead, UK: VSN International; 2022. Web page: Genstat.co.uk.

Peterson BG, Carl P, Boudt K, Bennett R, Ulrich J, Zivot E, Cornilly D, Hung E, Lestel M, Balkissoon K, Wuertz D, Christidis AA, Marttin DM, Zhou Z, Shea JM. Performance analytics: Econometric tools for performance and risk analysis. R package version 2.0.4. 2020; https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=PerformanceAnalytics.

Holland JB, Nyquist WE, Cervantes-Martinez CT. Estimating and interpreting heritability for plant breeding: an update. Plant Breed Rev. 2003;22:9–112.

Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A, Fennell T, Ruan J, Homer N, Marth G, Abecasis G, Durbin R. The sequence alignment/map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:2078–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352.

Li H, Durbin R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheelertransform. Bioinformatics. 2009;25:1754–60. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324.

Zhang C, Dong S, Xu J, He W, Yang T. PopLDdecay: a fast and effective tool for linkage disequilibrium decay analysis based on variant call format files. Bioinformatics. 2019a;35:1786–8. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/bty875.

Patterson N, Price AL, Reich D. Population structure and eigenanalysis. PLoS Genet. 2006;2:e190. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.0020190.

Tamura K, Stecher G, Peterson D, Filipski A, Kumar S. MEGA6: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 6.0. Mol Biol Evol. 2013;30:2725–9. https://doi.org/10.1093/molbev/mst197.

Jiang L, Zheng Z, Fang H, Yang J. A generalized linear mixed model association tool for biobank-scale data. Nat Genet. 2021;53:1616–21. https://doi.org/10.1038/S41588-021-00954-4.

Chiani M. Distribution of the largest eigenvalue for real Wishart and Gaussian random matrices and a simple approximation for the Tracy-Widom distribution. J Multivar Anal. 2014;129:69–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmva.2014.04.002.

Bradbury PJ, Zhang Z, Kroon DE, CAsstevens TM, Ramdoss Y, Buckler ES. TASSEL: software for association mapping of complex traits in diverse samples. Bioinf (Oxford England). 2007;23:2633–5. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btm308.

Zhou X, Stephens M. Genome-wide efficient mixed-model analysis for association studies. Nat Genet. 2012;44:821–4. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng.2310.

Turner SD. Qqman: an R package for visualizing GWAS results using Q-Q and manhattan plots. JOSS. 2018;3:731. https://doi.org/10.21105/joss.00731.

Dong S, He W, Ji J, Zhang C, Guo Y, Yang T. LDBlockShow: a fast and convenient tool for visualizing linkage disequilibrium and haplotype blocks based on variant call format files. Brief Bioinform. 2020;22:227. https://doi.org/10.1093/bib/bbaa227.

Chen H, Boutros PC. VennDiagram: a package for the generation of highly-customizable Venn and Euler diagrams in R. BMC Bioinformatics. 2011;12:1–7. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2105-12-35.

Conway JR, Lex A, Gehlenborg N. UpSetR: an R package for the visualization of intersecting sets and their properties. Bioinformatics. 2017;33:2938–40. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btx364.

Wei X, Liu K, Zhang Y, Feng Q, Wang L, Zhao Y, Li D, Zhao Q, Zhu X, Zhu X, Li W, Fan D, Gao Y, Lu Y, Zhang X, Tang X, Zhou C, Zhu C, Liu L, Zhong R, Tian Q, Wen Z, Weng Q, Han B, Huang X, Zhang X. Genetic discovery for oil production and quality in sesame. Nat Commun. 2015;6:8609. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms9609.

Gu J, Guo M, Deng L, Ren L, Miao J, Yin J, Li Y. Breeding value of high oleic acid peanut corner stone parent Kaixuan 016 based on coefficient of parentage. J Henan Agric Sci. 2018;47:47–52. https://doi.org/10.15933/j.cnki.1004-3268.2018.09.008.

Guo M, Yin J, Deng L, Miao J, Li Y, Lu Z, Fang Y, Li S, Ren L. Genetic diversity analysis on Kainong series cultivars of high oleic acid peanut (Arachis hypogaea L). J Peanut Sci. 2020;49:14–22. https://doi.org/10.14001/j.issn.1002-4093.2020.04.003.

Myles S, Peiffer J, Brown PJ, Ersoz ES, Zhang ZW, Costich DE, Buckler ES. Association mapping: critical considerations shift from genotyping to experimental design. Plant Cell. 2009;21:2194–202. https://doi.org/10.1105/tpc.109.068437.

Alqudah AM, Sallam A, Baenziger PS, Börner A. GWAS: fast-forwarding gene identification and characterization in temperate cereals: lessons from barley -a review. J Adv Res. 2020;22:119–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jare.2019.10.013.

Zhao Y, Li X, Chen Z, Lu H, Liu Y, Zhang Z, Liang C. An overview of genome-wide association studies in plants. Chin Bull Bot. 2020;55:715–32. https://doi.org/10.11983/CBB20091.

Zhang H, Chu Y, Dang P, Tang Y, Jiang T, Clevenger JP, et al. Identification of QTLs for resistance to leaf spots in cultivated peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.) through GWAS analysis. Theor Appl Genet. 2020;133:2051–61. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00122-020-03576-2.

Zhang H, Wang ML, Dang P, Jiang T, Zhao S, Lamb M, Chen C. Identification of potential QTLs and genes associated with seed composition traits in peanut (Arachis hypogaea) using GWAS and RNA-Seq analysis. Gene. 2020;769. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gene.2020.145215.

Njintang NY, Dolinassou S, Noubissie TJB. Heritability studies of protein and oil contents in groundnut (Arachis hypogaea L.) genotypes. Int J Innovations Bio-Sciences. 2012;2:162–71.

Zhao J, Huang L, Ren X, Pandey MK, Wu B, Chen Y, Zhou X, Chen W, Xia Y, Li Z, Luo H, Lei Y, Varshney RK, Liao B, Jiang H. Genetic variation and association mapping of seed-related traits in cultivated peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.) using single-locus simple sequence repeat markers. Front Plant Sci. 2017;8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2017.02105.

Killi F, Beycioğlu T. Genetic and environmental variability, heritability and genetic advance in pod yield, yield components, oil and protein content of peanut varieties. Turkish J Field Crops. 2022;27:71–7. https://doi.org/10.17557/tjfc.1050448.

Janila P, Manohar SS, Patne N, Variath MT, Nigam SN. Genotype × environment interactions for oil content in peanut and stable high-oil-yielding sources. Crop Sci. 2016;56:1–10. https://doi.org/10.2135/cropsci2016.01.0005.

Pandey MK, Chaudhari S, Jarquin D, Janila P, Crossa J, Patil SC, Sundravadana S, Khare D, Bha RS, Radhakrishnan T, Hickey JM, Varshney RK. Genome-based trait prediction in multi- environment breeding trials in groundnut. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2020;133:3101–3117. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00122-020-03658-1.

Zhang X, Zhang J, He X, Wang Y, Ma X, Yin D. Genome-wide association study of major agronomic traits related to domestication in peanut. Front. Plant Sci. 2017;8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpls.2017.01611.

Zou J, Qi Q, Katavic V, Marillia E-F, Taylor DC. Effects of antisense repression of anArabidopsis Thaliana pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase cDNA on plant development. Plant Mol Biol. 1999;41:837–49. https://doi.org/10.1023/a:1006393726018.

Hoffmann L, Maury S, Martz F, Geoffroy P, Legrand M. Purification, cloning, and properties of an acyltransferase controlling shikimate and quinate ester intermediates in phenylpropanoid metabolism. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:95–103. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M209362200.

Comino C, Lanteri S, Portis E, Acquadro A, Romani A, Hehn A, Romain L, Bourgaud F. Isolation and functional characterization of a cDNA coding a hydroxycinnamoyltransferase involved in phenylpropanoid biosynthesis in Cynara cardunculus L. BMC Plant Biol. 2007;7:14. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2229-7-14.

Petersen M. Hydroxycinnamoyltransferases in plant metabolism. Phytochem Rev. 2016;15:699–727. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11101-015-9417-1.

Wang J, Wang H, Yang H, Hu R, Wei D, Tang Q, Wang Z. The role of NAC transcription factors in flower development in plants. Chin J Biotech. 2022;38:2687–99. https://doi.org/10.13345/j.cjb.210943.

Nakashima K, Tran L-SP, Van Nguyen D, Todaka D, Ito Yl, Hayashi N, Shinozaki K, Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K. Functional analysis of a NAC-type transcription factor OsNAC6 involved in abiotic and biotic stress-responsive gene expression in rice. Plant J. 2007;51:617–30. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-313X.2007.03168.x.

Tello J, Torres-Pérez R, Grimplet J, Carbonell-Bejerano P, Matinez-Zapater JM, Ibanez J. Polymorphisms and minihaplotypes in the VvNAC26 gene associate with berry size variation in grapevine. BMC Plant Biol. 2015;15:253. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-015-0622-2.

Yang Y, Li Y, Cheng Z, Su Q, Jin X, Song Y, Wang J. Genetic analysis and exploration of major effect QTLs underlying oil content in peanut. Theor Appl Genet. 2023;136:97. https://doi.org/10.1007/S00122-023-04328-8.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the reviewers and editors who all provided useful feedback on this manuscript. The authors would like to thank Mr. Liu for his assistance with English editing.

Funding

This work was supported by Major Science and Technology Project of Henan Province (221100110300), Agriculture Research System of China (CARS-13), Agricultural Project for Variety Improvement of Henna Province (20220100001), and Key Research and Development Project of Kaifeng (19ZD004).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MG and LD performed data analysis, data curation, method development and the preparation of the original draft. ZS and FQ performed laboratory work. JM, JY, YL, ZL, SL, JH, YF, WD performed field investigation and data collection and preparation of experiments. BH performed manuscript preparation, editing and review. JG, XZ, and LR conceived this study, and are responsible for funding acquisition and project administration.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations of institutional, national, and international guidelines and legislation.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that there are no competing interests among the authors.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Guo, M., Deng, L., Gu, J. et al. Genome-wide association study and development of molecular markers for yield and quality traits in peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.). BMC Plant Biol 24, 244 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-024-04937-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-024-04937-5