Abstract

Background

The impacts of increasing nitrogen (N) deposition and overgrazing on terrestrial ecosystems have been continuously hot issues. Grazing exclusion, aimed at restoration of grassland ecosystem function and service, has been extensively applied, and considered a rapid and effective vegetation restoration method. However, the synthetic effects of exclosure and N deposition on plant and community characteristics have rarely been studied. Here, a 4-year field experiment of N addition and exclusion treatment had been conducted in the desert steppe dominated by Alhagi sparsifolia and Lycium ruthenicum in northwest of China, and the responses of soil characteristics, plant nutrition and plant community to the treatments had been analyzed.

Results

The grazing exclusion significantly increased total N concentration in the surface soil (0-20 cm), and increased plant height, coverage (P < 0.05) and aboveground biomass. Specifically, A. sparsifolia recovered faster both in individual and community levels than L. ruthenicum did after exclusion. There was no difference in response to N addition gradients between the two plants.

Conclusions

Our findings suggest that it is exclusion rather than N addition that has greater impacts on soil properties and plant community in desert steppe. Present N deposition level has no effect on plant community of desert steppe based on short-term experimental treatments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Background

The increasing aerial nitrogen (N) deposition derived from the intensification of both agricultural and industrial activities is affecting the ecosystems worldwide. As Moore had pointed out that it is too much of a good thing [1], the increased N deposition can change the nutrient and moisture status of the soil [2, 3], alter nutrient cycle of ecosystems [4], facilitate the growth of nitrophilic plants [5, 6], deteriorate biological diversity [7, 8], even alter community structure, composition and function of terrestrial ecosystems [5, 7, 9,10,11]. These effects are more likely to be found in some N-limited terrestrial ecosystems such as vegetation in arid environment [9, 12,13,14].

One of the important causes of the above consequences is that the increased available N changes the way plants use and recycle nutrients, such as nutrient allocation patterns, foliar chemistry and nutrient resorption [5, 15]. Nutrient resorption, a process of nutrient transferring from senescent tissues to mature tissues [16], is one of the key nutrient conservation strategies, therefore, has considerable adaptive and functional significance [5], specifically for plants in oligotrophic environment. Generally, plant nutrient resorption is associated with plant functional forms (for examples, legume and non-legume) [17, 18], and strongly influenced by nutrient availability [19]. Symbiotic N fixation broadens potential N resources and generally increases N absorption, which results in stable N concentration and N resorption in legumes [14, 17, 18]. Nutrient resorption patterns can also be altered by soil nutrient availability, although the divergent results have been found based on either inter- or intra-species studies [5, 16, 20]. Given the increasing N deposition scenarios, studies demonstrated that N addition resulted in higher availability of soil inorganic N [21], thus increased the leaf N and phosphorous (P) concentrations [22, 23], and decreased the nutrient resorption efficiency [20, 24]. However, even in the same experiment, species-scale nutrient resorption was different in response to N addition. For example, Lü et al. found that only half of the measured species reduced both N and P resorption efficiency in response to increased N inputs in a temperate steppe [5]. The diverse results indicate that more manipulate experiments are needed for better understanding the regulating mechanisms of N enrichment on ecosystem productivity and predicting plant community composition in a nutritionally restricted ecosystem such as desert steppe .

Arid area, accounting for 41% of the earth's land and supporting 38% of the population, is one of the most sensitive ecosystems responding to global change [25, 26]. Overgrazing have led to severe soil degradation, decrease in vegetation coverage [27, 28], ultimately, lowered the productivity [29]. These consequences have been more common in northwestern China in the past decades [30]. As one of the most extensive approaches, exclusion has been implemented for self-recovery of the overgrazed desert since 2004 in China [29, 31]. Generally, grazing exclusion can effectively facilitate soil fertility [32], increase plant N concentration [33, 34], vegetation coverage and plant composition [35, 36], therefore, increase the biomass accumulation of plant communities and facilitate vegetation restoration [37, 38]. However, the inconsistent results were also obtained [39,40,41]. Therefore, the knowledge is critical for a comprehensive understanding of the effects of grazing exclusion and N addition on soil properties, plant nutrition and vegetation recovery in this area. Here, 4-year N addition and grazing exclusion experiments were conducted in the desert steppe consisting of a legume and a non-legume species at western Hexi Corridor in China. We hypothesized that (1) exclusion would have a better protective effect on legume, while no or a few effects on non-legume because of the preference of livestock for legume; (2) N addition would increase the nutrient concentrations in soil and plant tissues, promote plant growth, improve aboveground biomass, specifically for non-legume living in low N environment such as desert steppe. To assess the above hypotheses, we determined nutrient status (N and P concentrations) of plant tissues and soil, and investigated plant cover, height and plant aboveground biomass. Our aim addresses to (1) discover the responses of the soil and plant nutrient characteristics to N deposition and exclusion in the desert steppe; (2) reveal the synergistic effect of N deposition and exclusion on plant community structure.

Methods

Study site

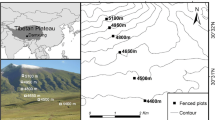

This study was conducted in a desert steppe ecosystem (aridity index < 0.02) located at the experimental area of Anxi Extra-arid Desert National Nature Reserve (40°16' 56.90” N, 96°11' 52.70” E, 1325 m a.s.l) at western Hexi Corridor in Gansu province, China (Fig. 1), with a mean annual temperature of 8.7°C, a mean annual precipitation of 45 mm, and an annual evaporation of 3000 mm [42]. The harsh environment restricted human activities to traditional uses, grazing with minimal agriculture. Based on investigation when the blocks set up, the vegetation is dominated by Lycium ruthenicum Murr. and Alhagi sparsifolia Shap. accompanied by Achnatherum splendens (Trin.) Nevski and Scorzonera mongolica Maxim (Table Sup. 1). A. sparsifolia is a perennial semi-shrub belonging to Leguminosae with a good feeding value [43], while L. ruthenicum is a representative perennial shrub belonging to Solanaceae. Both plants possess well-developed root system, drought tolerance and salinity tolerance, which make them dominant vegetation in sandy environment. Dominant grazing animal in the region is sheep. The grazing intensity (with a stocking rate of 2.43 sheep ha-1 year-1) in the rangeland is high [42].

Location of the study site (a) (from https://www.webmap.cn) and the experimental design (b), in which EX-0, EX-1, EX-3, EX-5 and FG-0 represent the amount of added nitrogen, 0, 1, 3, and 5 g N m-2 a-1 under fence treatments, respectively. Subfigure (c) shows the vegetation in enclosure (left of fence) and in grazing (right of fence) blocks

Experimental design

Four enclosed blocks were set up and then N addition and enclosing started in 2014. Each block contains 4 of 10 m × 10 m plots. The blocks and plots were separated by buffer zones of 5 m gaps. N addition was conducted in the form of NH4NO3 under gradients of 0, 1, 3, and 5 g N m-2 a-1, hereafter, the enclosed plots were denoted as EX-0, EX-1, EX-3 and EX-5 (Fig. 1). Meanwhile, four plots not less than 15m apart from each other were established in the grazing area as controls, named as FG-0. The exclusion and control sites were located in the same homogeneous ecological units. Half of the fertilizer was dissolved in 10 L water and applied to the plots with a portable sprayer in a rainy or cloudy day in end of May and July, respectively. For EX-0 and FG-0 plots, only 10 L of water was sprayed. The highest N addition level (EX-5, 5 g N m-2 a-1) was equivalent to the current maximum N deposition at the northern China plain [44].

Sampling and chemical analysis

Representative sun-exposed, full-expanded mature leaves of the dominant plant species, L. ruthenicum and A. sparsifolia, were sampled not less than 100 g from not less than five individuals in each plot in middle of July (the peak growing period) and in September (recently senesced, often yellow) in 2018 [13], respectively. The samples were mixed thoroughly in a paper envelope and taken back to the laboratory. After oven-dried at 80°C to a constant weight, the samples were ground using a ball mill (MM 400; Retsch, Haan, Germany) and sieved through a 0.25 mm mesh screen for chemical analysis [45].

The soil samples were collected and treated according to the methods of previous study [46]. The triplicate surface layer (0-20cm) soil samples were taken randomly from each plot in July when the plant samples were collected. Fresh soil was placed in an aluminum box and weighed in situ using an electronic balance, and then dried at 105°C for 24 h in the laboratory to determine the soil water content. The remaining air-dried soil samples were sieved through a 0.15 mm sieve to remove roots and litter residue, and then ground into a fine powder using a ball mill. Soil electrical conductivity and pH were measured on 1: 5 soil : water extracts (2220, Spectrum, USA) and 1 : 2.5 with a pH electrode (IQ150, Spectrum, USA), respectively. The available N (NH+ 4-N and NO- 3-N) was determined using a FIAstar 5000 Analyzer (Foss Tecator, Denmark). Total N was measured by an elemental analyzer (FLASHEA 1112 Series CNS Analyzer, Termo, USA). Total P was determined using the ammonium molybdate method after persulfate oxidation.

In the growth peak season (July), three subplots of 3 m×3 m were set in each plot of the enclosed and free grazing areas. The plant height, species and community coverage and plant density were measured and recorded in each subplot. At the same time, the aboveground parts of A. sparsifolia and the leaves and current year's branches of L. ruthenicum were collected for the calculation of aboveground biomass. The species-sorted samples were oven-dried at 80°C for 48 h, then, the aboveground community biomass was estimated through total dry mass of all living species per subplot averaged over all replicates of each treatment [47].

Nutrient resorption efficiency calculations

RE of N and P (NRE and PRE, respectively) was calculated for each species and expressed as the following [20]:

in which Nugreen and Nusenesced are N or P concentration of green or senesced leaves (Ngreen, Pgreen, Nsenesced, Psenesced, respectively) based nutrient mass per leaf dry mass, respectively.

Statistical analysis

Levene's test was used to test for normality of all data before statistical analysis, and the data were log 10 transformed when it was necessary to obtain approximate normality and homogeneity of residuals. The means of leaf N, P concentrations and physicochemical properties of the soil for each N addition rate were separated by using multiple comparison. One-way ANOVA (Duncan test) was used to test the impacts of treatments on leaf N, P concentrations and nutrient RE. The relationships between soil nutrient concentrations, physicochemical properties and plant leaf element concentrations were analyzed by Pearson correlation. The independent samples t-test was used to determine the differences in plant N and P concentrations between L. ruthenicum and A. sparsifolia under each treatment. All data analysis and mapping were conducted with SPSS version 18.0, Origin 8.0 and ArcGIS 10.2. The significance level was set at P = 0.05 for all calculations.

Results

Soil physicochemical properties and nutrient characteristics

The higher total N concentration was found in the soil of enclosure than that in the free grazing area (P < 0.05) (Table 1). Specifically, exclusion significantly increased soil NH+ 4-N and NO- 3-N concentrations (in EX-0), and decreased the soil pH and soil water content than free grazing did (FG-0) (P < 0.05). The N addition rates increased the soil NH+ 4-N concentration (P < 0.05) (Table 1), however, demonstrated no significant effect on the soil NO- 3-N and total N concentrations, pH, EC and soil water content in the enclosed sites (P > 0.05) (Table 1).

Leaf element concentrations and nutrient resorption efficiency

Compared with free grazing, the exclusion treatment decreased Pgreen of A. sparsifolia (P < 0.05) (Fig. 2 d), but showed no significant effect on Ngreen of both plants (Fig. 2 a). However, the exclusion treatment decreased Nsenesced and Psenesced of A. sparsifolia (P < 0.05), and showed no significant effect on both Nsenesced and Psenesced of L. ruthenicum (Fig. 2 b, e). The N addition increased Pgreen and Psenesced of A. sparsifolia (Fig. 2 d, e). It is worth noting that the Nsenesced in A. sparsifolia was significantly lower than that in L. ruthenicum (P < 0.05) at each N addition treatment level (Fig. 2 b).

Nitrogen concentrations (N, a, b), phosphorus concentrations (P, d, e) in green (a, d) and senesced leaves (b, e) of Lycium ruthenicum (Lr) and Alhagi sparsifolia (As), N (c) and P (f) resorption efficiency of L. ruthenicum and A. sparsifolia after 4 years nitrogen addition and exclosure (EX)/free grazing (FG) treatments in arid desert steppe. The columns marked with different letters differ significantly between EX and FG, and among additional nitrogen treatments in L. ruthenicum and A. sparsifolia, respectively (ANOVA Duncan test, P < 0.05). * and ** represent significant differences between L. ruthenicum and A. sparsifolia at P < 0.05 and P < 0.01 level (t-test), respectively

N addition increased NRE and PRE of A. sparsifolia (P < 0.05) (Fig. 2 c, f), however, no significant change was detected in L. ruthenicum (Fig. 2 c, f). The exclusion treatment significantly increased NRE of the two plants (P < 0.05) (Fig. 2 c), but showed no effect on PRE of A. sparsifolia and decreased PRE of L. ruthenicum (P < 0.05) (Fig. 2 f) compared with free grazing. A. sparsifolia had significantly higher NRE and PRE than L. ruthenicum except for PRE in FG-0 (P < 0.01) (Fig. 2 c, f).

Community characteristics after enclosure and nitrogen addition

Exclusion dramatically increased the community Shannon-Wiener Index and the Simpson Index (Table 2), the vegetation coverage and height (Table 3) than those of grazing treatment (P < 0.05). Specifically, the exclusion increased annual aboveground biomass (P < 0.05) despite of no significant difference in plant density compared with free grazing (Table 3). Exclusion decreased the relative coverage of L. ruthenicum but increased the height and the relative coverage of A. sparsifolia (Fig. 3). However, 4-year N addition presented no effect on the above traits (Table 2 and Table 3).

Relative density (%, a), relative coverage (%, b) and height (cm, c) of Lycium ruthenicum and Alhagi sparsifolia in the enclosure (EX-0) and the free grazing sites (FG-0). Different letters represent significant differences of the same species between EX-0 and FG-0 at P < 0.05, while * represents significant differences between L. ruthenicum and A. sparsifolia under the same treatments at P < 0.05 level (t-test)

Relationships between leaf element concentrations and environmental factors

Pearson correlation analysis showed Ngreen concentrations of the two plants were significantly positively correlated with the total N concentration in the soil, but negatively correlated with soil pH (P < 0.05) and soil electrical conductivity (P < 0.05), while there was no significant correlation between P concentrations in leaves and soil, respectively (Table 4).

Discussion

Grazing exclusion enhanced soil N concentration but had no effect on plant nutrients

Grazing exclusion did not enhance Ngreen of the two plants in this study, which is inconsistent with the previous studies. An & Li (2015) found the leaf N concentration of some species in grazing areas was higher than that in enclosures [34]. They contended that the grazing facilitates the elimination of senescent tissues on the ground and the produce of young tissues with higher nutrient concentration [48]. Therefore, species with high N concentration under the disturbance of grazing is a manifestation of super-compensated growth of plants. On the contrary, Wigley et al. [33] found increased plant N concentration under exclusion treatment which mainly derived from reduction of soil pH and increase in soil nutrients. Given the extreme low soil moisture content (2.8% - 7.46%) in this study, we speculate that soil water availability may be the more important limiting factor for plants nutrient distribution and survival [49], despite of no change in Ngreen in enclosure and no significant correlation between concentrations of N, P in leaves and soil water content. However, more detailed studies would be conducted to show how water and nutrients work together to affect plant survival.

The mass-based measure of nutrient RE may lead to an underestimation of real RE [50], which should be the main reason for the lower NRE and PRE in this study compared with the other studies [13, 16, 20]. However, the underestimation does not affect the difference in nutrient RE among treatments, and the conclusion of this study. Different from Ngreen, NRE of A. sparsifolia increased significantly after grazing exclusion, which should be the consequence of growth dilution of N concentration due to rapid growth after grazing exclusion [51, 52]. As a manifestation of super-compensated, the enhanced Pgreen resulting from inhibition of growth of L. ruthenicum in enclosure accounts for the decreased PRE. The increased total N of soil in the enclosure is consistent with the previous study performed in typical desert [30], and could be attributed to the following account. The increased vegetation coverage and aboveground biomass resulting in exclosure provided good conditions and source for enrichment of total N and organic matter in soil. Therefore, grazing exclusion is an effective method to deal with ecological degradation in arid regions [53].

Nitrogen addition did not increase the nitrogen concentrations of soil and leaves as expected

Previous studies demonstrate that N addition increased significantly soil N concentrations [54, 55], enhanced Ngreen [22, 31] and reduced foliar NRE [24], which had been attributed to the consequence that the N added to the soil can be quickly converted into available N for plant, and the N level in these plants depends more on soil N resources rather than resorbing from senescent tissues [22, 54, 55]. However, the inconsistent results with the above studies and as we had expected had been found that N addition did not lead to general increase in soil and plant N concentrations. The contrary results should be mainly attributed to the lower dose of N addition employed in this study than that in the other studies. For examples, 20 g N m-2 a-1 and 10 g N m-2 a-1 had been employed to simulate N deposition in temperate grassland and temperate forest [55], respectively, while the maximum N addition ratio in this study is 5 g N m-2 a-1, which is the current largest volume of annual N deposition at the study area [44]. Specifically, the local arid climate, strong evaporation and extreme low soil moisture decrease the mobility and availability of soluble and diffusible substrates and product, severely limit the turnover of soil nutrients, thus affect the availability of nutrients [13]. Therefore, the N addition does not present the expected effect in this study.

The result that nutrient resorption responding to N enrichment was variable at species-scale is consistent with the other study [5]. There is good possibility stemming from the following to interpret the higher Nsenesced and Psenesced and lower NRE and PRE in L. ruthenicum rather in A. sparsifolia at each treatment level. Firstly, A. sparsifolia produces more aboveground biomass each year than L. ruthenicum dose. Therefore, more nutrients are needed for A. sparsifolia than L. ruthenicum under the same growth conditions. In term of survival strategy, A. sparsifolia is a fast grower, while L. ruthenicum is more conservative ones. Furthermore, livestock prefers legume A. sparsifolia rather than L. ruthenicum, so the exclosure is more favorable for the growth and biomass accumulation of A. sparsifolia, rather than for L. ruthenicum. The strong “dilution effect” on N and other nutrients [51, 52] resulting from rapid biomass accumulation in A. sparsifolia leads to relative lower nutrient concentration and higher resorption efficiency.

Exclusion rather than nitrogen addition plays a greater role in maintenance of plant community

The short-term exclusion significantly increased the plant coverage, height and aboveground biomass, and improved the community productivity, which may mainly due to the reduction in food intake by livestock [37, 56, 57]. The fact that the exclusion treatment increased growth of A. sparsifolia rather than L. ruthenicum should due to the following facts. Since A. sparsifolia, a leguminous plant, not L. ruthenicum, is preferred by livestock, therefore, the protective effects of livestock exclusion were much greater on A. sparsifolia than that on L. ruthenicum. On the other hand, the aboveground part of A. sparsifolia is annual, which has a faster growth rate than L. ruthenicum dose. Therefore, the relative coverage, height and biomass of A. sparsifolia increased significantly than L. ruthenicum after exclusion treatment. The asymmetric effect of exclusion treatment on the two plants will further lead to the change that A. sparsifolia may be the only dominant plant after a longer period of livestock exclusion. The results of N addition experiments overturned our previous hypothesis that the higher N addition will promote rapid growth of non-legume and possibly make it the dominant species. This study also suggests that the current level of N deposition has no effect on structure of plant community in the study area. In addition to the lower level of N addition compared with the other experiments, extremely low soil moisture content should be another key role limiting plant nutrient contents and survival in the arid area [49], directly or indirectly, which, however, needs detailed studies and more data to support. Synthetically, in arid areas with low biodiversity, free grazing rather than N deposition more seriously affected local fragile vegetation. Grazing exclusion can not only increase vegetation coverage and aboveground biomass, but also change the community structure and composition of vegetation, which is far more than the effect of current N deposition level. The impacts of N deposition and exclusion on the vegetation in the desert region still require long-term research. Strategy of moderate grazing rather than absolute isolation should be adopted in process of ecological restoration in arid desert regions.

Conclusions

In the present study, a 4-year field experiment had been conducted to test the responses of soil properties, plant nutrition and plant community to the N addition and exclusion treatments in the desert steppe in northwest of China. Short-term grazing exclusion significantly increased the soil total N, available N, and increased the plant height, coverage, improved the aboveground biomass. Specifically, legumes A. sparsifolia had recovered more than L. ruthenicum after exclusion. N addition, however, presented divergent effects on leaf nutrients of the two plants, and no effect on community characteristics. In short, the grazing exclusion, rather than N addition, has greater influence on plant community and surface soil of the desert steppe.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Abbreviations

- N:

-

Nitrogen

- P:

-

Phosphorus

- NRE, PRE:

-

Nutrient resorption efficiency of nitrogen, or phosphorous

- Ex:

-

exclosure

- FG:

-

Free grazing

References

Moore PD. Too much of a good thing. Nature. 1995;374:117–8 https://doi.org/10.1038/374117a0.

Richter A, Burrows JP, Nuss H, Granier C, Niemeier U. Increase in tropospheric nitrogen dioxide over China observed from space. Nature. 2005;437:129–32 https://doi.org/10.1038/nature04092.

Fan YX, Zhong XJ, Lin TC, Lyu MK, Wang MH, Hu WF, et al. Effects of nitrogen addition on DOM-induced soil priming effects in a subtropical plantation forest and a natural forest. Biol Fertil Soils. 2020;56(2):205–16 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00374-019-01416-0.

Liu LL, Greaver TL. A review of nitrogen enrichment effects on three biogenic GHGs: the CO2 sink may be largely offset by stimulated N2O and CH4 emission. Ecol Lett. 2010;12(10):1103–17 https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2009.01351.x.

Lü XT, Hou SL, Reed S, Yin JX, Hu YY, Wei HW, et al. Nitrogen enrichment reduces nitrogen and phosphorus resorption through changes to species resorption and plant community composition. Ecosystems. 2021;24(3):602–12 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10021-020-00537-0.

Suding KN, Collins SL, Gough L, Clark C, Cleland EE, Gross KL, et al. Functional- and abundance-based mechanisms explain diversity loss due to N fertilization. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102(12):4387–92 https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0408648102.

Matson PA, Lohse KA, Hall SJ. The globalization of nitrogen deposition: consequences for terrestrial ecosystems. Ambio. 2002;31:113–9 https://doi.org/10.1579/0044-7447-31.2.113.

Clark CM, Tilman D. Loss of plant species after chronic low-level nitrogen deposition to prairie grasslands. Nature. 2008;451(7179):712–5 https://doi.org/10.1038/nature06503.

Lebauer DS, Treseder KK. Nitrogen limitation of net primary productivity in terrestrial ecosystems is globally distributed. Ecology. 2008;89(2):371–9 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10021-020-00537-0.

Penuelas J, Poulter B, Sardans J, Ciais P, Velde M, Bopp L, et al. Human-induced nitrogen-phosphorus imbalances alter natural and managed ecosystems across the globe. Nat Commun. 2013;4:2934 https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms3934.

Phoenix G, Hichs W, Cinderby S. Atmospheric nitrogen deposition in world biodiversity hotspots: the need for a greater global perspective in assessing N deposition impacts. Global Change Bio. 2006;12(3):470–6 https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2486.2006.01104.x.

Law B. Nitrogen deposition and forest carbon. Nature. 2013;496(7445):307–8 https://doi.org/10.1038/496307a.

Wang LL, Wang L, He WL, An LZ, Xu SJ. Nutrient resorption or accumulation of desert plants with contrasting sodium regulation strategies. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):17035 https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-17368-0.

Wang LL, Zhang XF, Xu SJ. Is salinity the main ecological factor that influences foliar nutrient resorption of desert plants in a hyper-arid environment? BMC Plant Biol. 2020;20:461 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-020-02680-1.

Farrer EC, Herman DJ, Franzova E, Pham T, Suding KN. Nitrogen deposition, plant carbon allocation, and soil microbes: Changing interactions due to enrichment. Am J Bot. 2013;100:1458–70 https://doi.org/10.3732/ajb.1200513.

Aerts R. Nutrient resorption from senescing leaves of perennials: Are there general patterns? J Ecol. 1996;84(4):597–608 https://doi.org/10.2307/2261481.

Hobbie SE. Plant species effects on nutrient cycling: revisiting litter feedbacks. Trends Ecol Evol. 2015;30:357–63 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tree.2015.03.015.

Wang ZN, Lu JJ, Yang HM, Zhang X, Luo CL, Zhao YX. Resorption of nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium from leaves of lucerne stands of different ages. Plant and Soil. 2014;383:301–12 https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-014-2166-x.

Pugnaire FI, Chapin FS. Controls over nutrient resorption from leaves of evergreen mediterranean species. Ecology. 1993;74:124–9 https://doi.org/10.2307/1939507.

Kobe RK, Lepczyk CA, Iyer M. Resorption efficiency decreases with increasing green Leaf nutrients in a global data set. Ecology. 2005;86:2780–92 https://doi.org/10.1890/04-1830.

Galloway JN, Cowling EB. Reactive nitrogen and the world: 200 years of change. Ambio A Journal of the Human Environment. 2002;31:64–71 https://doi.org/10.1579/0044-7447-31.2.64.

Huang JY, Zhu XG, Yuan ZY, Song SH, Li X, Li LH. Changes in nitrogen resorption traits of six temperate grassland species along a multi-level N addition gradient. Plant and Soil. 2008;306:149–58 https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-008-9565-9.

Xia JY, Wan SQ. Global response patterns of terrestrial plant species to nitrogen addition. New Phytol. 2008;179:428–39 https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8137.2008.02488.x.

Lü XT, Cui QA, Wang QB, Han XG. Nutrient resorption response to fire and nitrogen addition in a semi-arid grassland. Ecol Eng. 2011;37:534–8 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoleng.2010.12.013.

Reynolds JF, Smith DMS, Lambin EF, Mortimore M, Batterbury SPJ, Downing TE, et al. Global desertification: building a science for dryland development. Science. 2007;316:847–51 https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1131634.

Maestre FT, Salguero-Gomez R, Quero JL. It is getting hotter in here: Determining and projecting the impacts of global environmental change on drylands. Philos Trans R Soc B. 2012;367:3062–75 https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2011.0323.

Steffens M, Kölbl A, Totsche KU, Kögel-Knabner I. Grazing effects on soil chemical and physical properties in a semiarid steppe of Inner Mongolia (P.R. China). Geoderma. 2008;143:63–72 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2007.09.004.

Yao XX, Wu J, Gong X, Lang X, Wang C, Song S, et al. Effects of long term fencing on biomass, coverage, density, biodiversity and nutritional values of vegetation community in an alpine meadow of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Ecol Eng. 2019;130:80–93 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoleng.2019.01.016.

Deng L, Liu GB, Shangguan ZP. Land-use conversion and changing soil carbon stocks in China's 'Grain-for-Green' Program: a synthesis. Glob Chang Biol. 2014;20:3544–56 https://doi.org/10.1111/gcb.12508.

Zhang YY, Zhao WZ. Vegetation and soil property response of short-time fencing in temperate desert of the Hexi Corridor, northwestern China. CATENA. 2015;133:43–51 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catena.2015.04.019.

Wang XG, Lü XT, Han XG. Responses of nutrient concentrations and stoichiometry of senesced leaves in dominant plants to nitrogen addition and prescribed burning in a temperate steppe. Ecol Eng. 2014;70:154–61 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoleng.2014.05.015.

Hiernaux P, Bielders CL, Valentin C, Bationo A, Fernandez-Rivera S. Effects of livestock grazing on physical and chemical properties of sandy soils in Sahelian rangelands. J Arid Environ. 1999;41:231–45 https://doi.org/10.1006/jare.1998.0475.

Wigley BJ, Fritz H, Coetsee C, Bond WJ. Herbivores shape woody plant communities in the Kruger National Park: Lessons from three long-term exclosures. Koedoe. 2014;56:1–12 https://doi.org/10.4102/koedoe.v56i1.1165.

An H, Li GQ. Effects of grazing on carbon and nitrogen in plants and soils in a semiarid desert grassland, China. J Arid Land. 2015;7:341–9 https://doi.org/10.1007/s40333-014-0049-x.

Zhao HL, Zhou RL, Su YZ, Zhang H, Zhao LY, Drake S. Shrub facilitation of desert land restoration in the Horqin Sand Land of Inner Mongolia. Ecol Eng. 2007;31:1–8 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoleng.2007.04.010.

Korkan SY. Effects of afforestation on soil organic carbon and other soil properties. CATENA. 2014;123:62–9 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catena.2014.07.009.

Su YZ, Zhao HL, Zhang TH. Influences of grazing and exclosure on carbon sequestration in degraded sandy grassland, Inner Mongolia, north China. N Z J Agric Res. 2003;46:321–8 https://doi.org/10.1080/00288233.2003.9513560.

Mseddi K, Al-Shammari A, Sharif H. Plant diversity and relationships with environmental factors after rangeland exclosure in arid Tunisia. Turk J Bot. 2016;40:287–97 https://doi.org/10.3906/bot-1410-29.

Su YZ, Li YL, Cui JY, Zhao WZ. Influences of continuous grazing and livestock exclusion on soil properties in a degraded sandy grassland, Inner Mongolia, northern China. CATENA. 2005;59:267–78 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.catena.2004.09.001.

Xiong DP, Shi PL, Zhang XZ, Zou CB. Effects of grazing exclusion on carbon sequestration and plant diversity in grasslands of China A meta-analysis. Ecol Eng. 2016;94:647–55 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoleng.2016.06.124.

Zeng QC, Liu Y, Li X, Huang YM. How fencing affects the soil quality and plant biomass in the grassland of the Loess Plateau. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017;14:1117 https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph14101117.

Liu FZ, Zhang JL, Yang ZW, Wang L, Cui GF. Vegetation growth and conservation efficacy assessment in south part of Gansu Anxi National Nature Reserve in Hyper-Arid Desert. Acta Ecol Sin. 2016;36:1582–90 https://doi.org/10.5846/stxb201408191645.

Editorial Committee of Flora of China, Chinese Academy of Sciences. Flora of China. Beijing: Science Press; 2013.

Liu XJ, Zhang Y, Han WX, Tang AH. Enhanced nitrogen deposition over China. Nature. 2013;494:459–62 https://doi.org/10.1038/nature11917.

Zhang LF, Wang LL, He WL. Patterns of leaf N:P stoichiometry along climatic gradients in sandy region, north of China. Journal of Plant Ecology. 2018:218–25 https://doi.org/10.1093/jpe/rtw134.

Wang LL, Zhao GX, Li M, Xu SJ. C:N:P stoichiometry and leaf traits of halophytes in an arid saline environment, Northwest China. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(3):e0119935 https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0119935.

Bai YF, Han XG, Chen ZZ, Wu JG, Li LH. Ecosystem stability and compensatory effects in the Inner Mongolia grassland. Nature. 2004;431:181–4 https://doi.org/10.1038/nature02850.

Tessema ZK, de Boer WF, Baars RMT, Prinsa HHT. Changes in soil nutrients, vegetation structure and herbaceous biomass in response to grazing in a semi-arid savanna of Ethiopia. J Arid Environ. 2011;75:662–70 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaridenv.2011.02.004.

Ladwig LM, Collins SL, Swann AL, Xia Y, Allen MF, Allen EB. Above- and belowground responses to nitrogen addition in a Chihuahuan Desert grassland. 2012;169:177–85 https://doi.org/10.1007/s00442-011-2173-z.

Heerwaarden LM, Toet S, Aerts R. Current measures of nutrient resorption efficiency lead to a substantial underestimation of real resorption efficiency: facts and solutions. Oikos. 2003;101(3):664–9 https://doi.org/10.1034/j.1600-0706.2003.12351.x.

Kemp PR, Waldecker DG, Owensby CE, Reynolds JF, Virginia RA. Effects of elevated CO2 and nitrogen fertilization pretreatments on decomposition on tallgrass prairie leaf litter. Plant and Soil. 1994;165 https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00009968.

Heerwaarden LM, Toet S, Aerts R. Nitrogen and phosphorus resorption efficiency and proficiency in six sub-arctic bog species after 4 years of nitrogen fertilization. J Ecol. 2010;91:1060–70 https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2745.2003.00828.x.

Li YQ, Zhao HL, Zhao XY, Zhang TH, Li YL, Cui JY. Effects of grazing and livestock exclusion on soil physical and chemical properties in desertified sandy grassland, Inner Mongolia, northern China. Environ Earth Sci. 2011;63:771–83 https://doi.org/10.1007/s12665-010-0748-3.

Gao Y, He NP, Zhang XY. Effects of reactive nitrogen deposition on terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems. Ecol Eng. 2014;70:312–8 https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoleng.2014.06.027.

Kazanski CE, Riggs CE, Reich PB, Hobbie SE. Long-term nitrogen addition does not increase soil carbon storage or cycling across eight temperate forest and grassland sites on a sandy outwash plain. Ecosystems. 2019;22:1592–605 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10021-019-00357-x.

Cheng J, Wu GL, Zhao LP. Cumulative effects of 20-year exclusion of livestock grazing on above- and belowground biomass of typical steppe communities in arid areas of the Loess Plateau, China. Plant Soil Environ. 2011;57:40–4 https://doi.org/10.17221/153/2010-PSE.

Zhou ZY, Li FR, Chen SK, Zhang HR, Li GD. Dynamics of vegetation and soil carbon and nitrogen accumulation over 26 years under controlled grazing in a desert shrubland. Plant and Soil. 2011;341:257–68 https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-010-0641-6.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Wenliang He, Ting Yu, Tianjiao He, Chen Wang, Jun Ma for field work, Renyi Zhang and Caixia Wu for laboratory analyses, Dr. Wenrui Wang for mapping the sampling sites, Dr. Xing-e Qi for data analysis and the figure revision. Comments from anonymous reviewers and editors contributed substantially to the manuscript’s improvement.

Funding

This study was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (31570393), the State Key Basic Research and Development Plan (2013CB429904), The 6th Maintenance Project of National Biodiversity Field Monitoring Base.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M L, L L W and S X conceived and designed the experiments; M L, J L, L W and Z P performed the experiments; X Z and M L analyzed the data and prepared the figures; M L and S X drafted the manuscript; L L W and S X have revised the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The enclosed and the grazing blocks locate at the experimental area of Anxi Extra-arid Desert National Nature Reserve, and were authorized and assisted by the Anxi Extra-arid Desert Nature Reserve. No endangered or protected plant species was involved in this study. Our work reported here complies with the current laws of China and the IUCN Policy Statement on Research Involving Species at Risk of Extinction.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Table S1.

The community eigenvalue in EX and FG

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, M., Wang, L., Li, J. et al. Grazing exclusion had greater effects than nitrogen addition on soil and plant community in a desert steppe, Northwest of China. BMC Plant Biol 22, 60 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-021-03400-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12870-021-03400-z