Abstract

Background

Although urinary tract infections (UTIs) are extremely common, isolation of causative uropathogens is not always routinely performed, with antibiotics frequently prescribed empirically. This study determined the susceptibility of urinary isolates from two Health and Social Care Trusts (HSCTs) in Northern Ireland to a range of antibiotics commonly used in the treatment of UTIs. Furthermore, we determined if detection of trimethoprim resistance genes (dfrA) could be used as a potential biomarker for rapid detection of phenotypic trimethoprim resistance in urinary pathogens and from urine without culture.

Methods

Susceptibility of E. coli and Klebsiella spp. isolates (n = 124) to trimethoprim, amoxicillin, ceftazidime, ciprofloxacin, co-amoxiclav and nitrofurantoin in addition to susceptibility of Proteus mirabilis (n = 61) and Staphylococcus saprophyticus (n = 17) to trimethoprim was determined by ETEST® and interpreted according to EUCAST breakpoints. PCR was used to detect dfrA genes in bacterial isolates (n = 202) and urine samples(n = 94).

Results

Resistance to trimethoprim was observed in 37/124 (29.8%) E. coli and Klebsiella spp. isolates with an MIC90 > 32 mg/L. DfrA genes were detected in 29/37 (78.4%) trimethoprim-resistant isolates. Detection of dfrA was highly sensitive (93.6%) and specific (91.4%) in predicting phenotypic trimethoprim resistance among E. coli and Klebsiella spp. isolates. The dfrA genes analysed were detected using a culture-independent PCR method in 16/94 (17%) urine samples. Phenotypic trimethoprim resistance was apparent in isolates cultured from 15/16 (94%) dfrA-positive urine samples. There was a significant association (P < 0.0001) between the presence of dfrA and trimethoprim resistance in urine samples containing Gram-negative bacteria (Sensitivity = 75%; Specificity = 96.9%; PPV = 93.8%; NPV = 86.1%).

Conclusions

This study demonstrates that molecular detection of dfrA genes is a good indicator of trimethoprim resistance without the need for culture and susceptibility testing.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Urinary Tract Infections (UTIs) are among the most common bacterial infections that occur in primary care [1] and the second most common reason for prescription of antibiotics in England [2]. Treatment of UTI is most commonly empirical, based on clinical suspicion and/or a positive urine dipstick test. Although urine dipstick tests are rapid and can be used at the point of care, their value is primarily in their ability to rule out rather than confirm infection [3, 4]. Where further analysis of a urine sample is required, the presence of a uropathogen is established by microscopy, culture and subsequent antimicrobial susceptibility testing (AST). However, as conventional culture and AST may take up to 72 h, commencement of appropriate treatment may be delayed. This could lead to clinical complications as well as longer and more frequent hospitalization of patients such as the elderly and those who are immunocompromised [5].

Trimethoprim is currently only recommended as first-line treatment for UTIs if there is a low risk of resistance with nitrofurantoin, the antibiotic of choice [6]. However, patients prescribed nitrofurantoin frequently present with gastrointestinal side effects. Moreover, nitrofurantoin is not recommended for use in patients with poor renal function, defined as an estimated glomerular filtration rate < 45 ml/minute, which is common amongst the elderly. Therefore, trimethoprim remains the preferred choice for treatment of many UTIs. Gram-negative bacteria, particularly E. coli and Klebsiella spp., are the most commonly isolated uropathogens with high levels of trimethoprim resistance observed [7]. Resistance to trimethoprim was 39% in E. coli, 26.7% in Klebsiella spp. and 41.9% in Proteus mirabilis whereas resistance to nitrofurantoin was 4% in E. coli, 34.8% in Klebsiella spp. and 0% in Proteus mirabilis [8, 9]. In contrast, resistance is rare in Staphylococcus saprophyticus [10]. This study determined the susceptibility of urinary E. coli, Klebsiella spp., Proteus mirabilis and Staphylococcus saprophyticus isolates to a range of antibiotics commonly used in the treatment of UTIs. We also determined if there was an association between the prevalence of dfrA genes, conferring resistance to trimethoprim, with phenotypic trimethoprim resistance in both isolates and urine. Rapid determination of resistance profiles to first-line antibiotics would avoid unnecessary antibiotic prescription, aid clinical decision making and ultimately improve patient outcomes.

Materials and methods

Clinical bacterial isolates

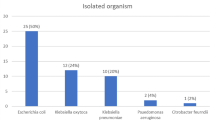

E. coli (n = 91), Klebsiella spp. (n = 33), Proteus mirabilis (n = 61) and Staphylococcus saprophyticus (n = 17) isolates were from culture-positive urine samples obtained from the Belfast and Northern Health and Social Care Trusts (BHSCT and NHSCT) routine diagnostic microbiology laboratories in October 2014. Isolates were grown on selective agar and identified using the VITEK® 2 system (bioMérieux, Marcy-l’Etoile, France). Following transfer to our laboratory, isolates were re-grown on Tryptone Soy Agar to obtain pure cultures and the identity of the isolates was confirmed by 16S rRNA marker-gene sequencing using primer pairs 27F (5′-AGAGTTTGATCMTGGCTCAG-3′) and 1492R (5′-TACGGYTACCTTGTTACGACTT-3′) [11].

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing

The antimicrobial susceptibility of E. coli and Klebsiella spp. isolates (n = 124) to amoxicillin, ceftazidime, ciprofloxacin, co-amoxiclav, nitrofurantoin and trimethoprim was determined by ETEST® (bioMérieux, Marcy-l’Etoile, France) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Susceptibility of Proteus mirabilis (n = 61) and S. saprophyticus (n = 17) to trimethoprim was also determined by ETEST®. The isolates were classified as susceptible, intermediate or resistant to each antibiotic according to the European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) MIC breakpoints [12].

Detection of trimethoprim resistance (dfrA) genes in clinical urinary isolates

The most common trimethoprim-resistance genes in Europe (dfrA1, dfrA5, dfrA7, dfrA12 and dfrA17) [13, 14], were detected by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification using the Applied Biosystems Veriti™ 96-Well Thermal Cycler (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Paisley, UK), with primers described in Table S1 (see Supplementary material). Genomic DNA was extracted from bacterial isolates using the DNeasy Blood and Tissue Kit (Qiagen®, Hilden, Germany) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions and all reactions were performed in uniplex. Based on the high homology between dfrA7 and dfrA17, one primer set (dfrA7/dfrA17) was designed to detect both genes. The final PCR reaction mixture (50 μL) for dfrA genes contained 0.4 μM of each forward and reverse primers (Eurofins MWG Operon, Ebersberg, Germany) and 1 μL of DNA template, with initial denaturation at 95 °C for 2 min; 30 cycles of denaturation at 95 °C for 30 s, annealing at 65 °C (dfrA1, dfrA5, dfrA12) or 55 °C (dfrA7/17) for 30 s and extension at 72 °C for 15 s; and a final extension at 72 °C for 5 min. DNA from isolates previously sequenced and confirmed to harbour the dfrA genes (dfrA1 – E. coli UM015; dfrA5 – E. coli UM176; dfrA7/17 – E. coli UM107; dfrA12 - K. pneumoniae UM282) were used as positive controls while DEPC-treated water (Ambion, Warrington, UK) was used as a negative control. The PCR products were separated by size on a 1.5% (w/v) agarose (Invitrogen, Paisley, UK) gel at 100 V for 30 min.

Culture-independent detection of trimethoprim resistance in urine

Ninety-four (94) urine samples were collected in May 2019 from the Routine Diagnostic Laboratory, BHSC, with ethical approval (ORECNI Reference: 17/SC/0302). These were samples submitted for routine urine culture and no patient metadata was collected. DNA was immediately extracted from these urine samples on the automated MagNA Pure 96 (Roche, Germany) platform using the DNA and viral NA small volume kit (Roche, Germany), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The extracted DNA was stored at − 20 °C before use as template in the PCR reaction. Microbiological culture of urine samples was performed on Brilliance UTI Clarity agar (Fannin L.I.P., Galway) and susceptibility testing of the isolates to trimethoprim was determined by ETEST®. The diagnostic performance of dfrA for predicting trimethoprim resistance using a culture-independent PCR method was determined and compared with phenotypic trimethoprim resistance.

Statistical analysis

The Chi-square test was performed to compare the antibiotic susceptibility between E. coli and Klebsiella spp. Fisher’s exact test was used to determine the association between the presence of dfrA genes and trimethoprim resistance. Isolates were grouped into Gram-positive and Gram-negative bacteria for the analysis of the association (Fisher’s exact test) between culture-independent detection of dfrA in urine samples and phenotypic trimethoprim resistance. All statistical analyses were carried out using GraphPad Prism 6 for Windows version 6.01 (GraphPad Software Inc., CA, USA). A P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Antimicrobial susceptibility of E. coli and Klebsiella spp. isolates

Trimethoprim resistance was phenotypically detected in 37/124 (29.8%) of the E. coli and Klebsiella spp. isolates. Four of these 37 (10.8%) trimethoprim-resistant isolates were resistant to trimethoprim only, 21/37 (56.8%) were resistant to an additional antibiotic, 10/37 (27%) were resistant to two additional antibiotics, while 2/37 (5.4%) were resistant to three additional antibiotics (Table 1). Data on susceptibility of E. coli and Klebsiella spp. isolates to all antibiotics tested are summarized in Table S2 (see Supplementary material). Fewer Klebsiella spp. isolates (7/33; 21.2%) showed intermediate or resistant phenotypes to trimethoprim than E. coli (31/91; 34.1%) isolates, although this difference was not statistically significant (P > 0.05; Chi-square test). Eighty-one of the 124 (65.3%) isolates were resistant to amoxicillin while 15/124 (12.1%) isolates were not susceptible to ciprofloxacin (Table 1). Resistance to nitrofurantoin was observed in 18/124 (14.5%) isolates and was more apparent in Klebsiella spp. (10/33; 30.3%) than in E. coli (8/91; 8.8%) isolates (P < 0.01; Chi-square test), with MIC90 values of > 512 and 24 mg/L, respectively. Nonetheless, significantly fewer Klebsiella spp. isolates were not susceptible to ciprofloxacin (6/33; 18.2%) than nitrofurantoin (10/33; 30.3%) (P < 0.05; Chi-square test).

dfrA as a marker for phenotypic trimethoprim resistance in E. coli and Klebsiella spp.

Of the 124 E. coli and Klebsiella spp. isolates, the dfrA gene targets were detected in 31 isolates comprising 28 E. coli (dfrA1, n = 13; dfrA5, n = 8; dfrA7/dfrA17, n = 7) and 3 Klebsiella spp. (dfrA1, n = 2 and dfrA12, n = 1) (Fig. 1). Representative gels for the detection of dfrA genes are shown in Fig. S1. Of the 31 trimethoprim-resistant E. coli isolates, dfrA was present in 27 (87.1%; dfrA1, n = 12; dfrA5, n = 8; dfrA7&17, n = 7); in contrast, it was only detected in 2/6 (33.3%; dfrA1, n = 2) trimethoprim-resistant Klebsiella spp. Furthermore, dfrA was detected in only 2/87 (2.3%; dfrA1, n = 1 and dfrA12, n = 1) trimethoprim-sensitive isolates. There was a significant association between the presence of dfrA and trimethoprim resistance among the isolates tested (P < 0.0001; Fisher’s exact test). The sensitivity and specificity of dfrA detection to determine phenotypic trimethoprim resistance compared to phenotypic susceptibility testing by ETEST® was 93.6 and 91.4% respectively, with a Positive Predictive Value (PPV) of 78.4% and a Negative Predictive Value (NPV) of 97.7%.

Trimethoprim resistance and dfrA detection in other uropathogens

The ability of dfrA to predict phenotypic trimethoprim resistance in other common urinary isolates, P. mirabilis and S. saprophyticus, was also investigated. Thirty-seven of 61 (60.7%) P. mirabilis isolates were resistant to trimethoprim (Range: 0.5 - > 32 mg/L; MIC50: 2 mg/L; MIC90: 6 mg/L) and dfrA was detected in 25/37 (67.6%). Only dfrA1 (25/25) was detected in trimethoprim-resistant P. mirabilis, with no dfrA genes detected in trimethoprim-sensitive P. mirabilis isolates (0/24). There was a significant association between the presence of dfrA and trimethoprim resistance among P. mirabilis isolates (P < 0.0001; Fisher’s exact test) [Sensitivity = 67.6%; Specificity = 100%; PPV = 100%; NPV = 66.7%]. Only 1/17 (5.9%) S. saprophyticus isolate was resistant to trimethoprim (MIC: > 32 mg/L) and none of the dfrA genes tested in this study were detected in S. saprophyticus isolates.

Culture-independent PCR detection of trimethoprim resistance in urine samples

Of the 94 urine samples tested, 92 (97.9%) were culture-positive and two samples (2.1%) had no detectable bacteria. Of the culture-positive samples, 55 (59.8%) were monomicrobial and 37 (40.2%) were polymicrobial (Table S3). Twenty of the 94 samples (21.3%) were positive by culture for bacteria which were phenotypically resistant to trimethoprim. DfrA genes were detected in 15/20 trimethoprim-resistant bacteria. DfrA genes were also detected by PCR in 16/94 (17%) urine samples (Table 2). Of these 16 urine samples positive for dfrA, dfrA-positive bacteria that were phenotypically resistant to trimethoprim were cultured from 15. In one urine sample (CU0000058), dfrA was detected by PCR but the isolate cultured from the sample was dfrA-negative and susceptible to trimethoprim. DfrA genes were not detected by PCR from two urine samples (CU0000042 and CU0000063), which were culture-positive for dfrA-positive isolates demonstrating phenotypic resistance to trimethoprim. Three additional urine samples (CU0000025, CU0000027 and CU0000078) with no detectable dfrA genes were culture-positive for isolates phenotypically not susceptible to trimethoprim. There was a significant association (P < 0.0001; Fisher’s exact test) between the presence of dfrA and phenotypic trimethoprim resistance in urine samples containing Gram-negative bacteria (Sensitivity = 75%; Specificity = 96.9%; PPV = 93.8%; NPV = 86.1%).

Discussion

This study demonstrates that phenotypic trimethoprim resistance can be rapidly and reliably predicted by molecular detection of dfrA genes in isolates and urine samples. Timely and appropriate initiation of antimicrobial therapy is key to effective antimicrobial stewardship policies. Rapid detection of trimethoprim resistance, prior to prescription of an antibiotic, could help avoid the risk of treatment failure [15], longer hospitalizations and UTI recurrence [16, 17]. Ongoing work by our group is focusing on the development of a point of care assay which will combine molecular detection of both uropathogens and trimethoprim resistance directly from urine. Such an assay could potentially be used in a range of primary and secondary care settings and may help determine potential resistance to antibiotics in a more clinically relevant timeframe which will guide appropriate antibiotic choice, particularly in patients for whom nitrofurantoin is not recommended.

The prevalence of trimethoprim resistance in E. coli reported in this study (34.1%) is similar to data reported for England in 2016 (34%) [18]; however, more recent data demonstrates that resistance in E. coli has decreased slightly in England (35.1%, 2015 vs. 31.2%, 2018) [19], Scotland (34.3%, 2015 vs. 33.8%, 2018) [20] and Wales (38.2%, 2015 vs. 36.6%, 2018) [21]. This reduction in trimethoprim resistance is associated with a decrease in trimethoprim use and an increase in nitrofurantoin prescribing for treatment of UTIs [19]. Although there is evidence of reduced trimethoprim use in primary care in Northern Ireland [22], there is currently no data with respect to the impact this is having on trimethoprim resistance among urinary isolates.

Despite high trimethoprim resistance rates, the current National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines for treatment of UTIs still recommend trimethoprim as first-line treatment in patient cohorts such as adult males ≥16 years old, non-pregnant women ≥16 years old and children aged ≥3 months, where there is low risk of resistance [6]. Results from this study have demonstrated that a PCR-based molecular test can be used to identify the risk of trimethoprim resistance from isolates and from urine without culture. Culture-independent detection of dfrA genes in urine results in a more rapid detection of trimethoprim resistance, with a 3–4 hour turnaround time. Furthermore, current phenotypic detection of trimethoprim resistance depends on determining susceptibility of the culture-predominant isolate. However, culture-independent testing of one urine sample in the current study demonstrated the presence of trimethoprim resistance, which was not identified based on phenotypic testing of the culture predominant organism.

In the current study, phenotypic trimethoprim resistance was detected in 37/124 (29.8%) E. coli and Klebsiella spp. isolates and at least one dfrA gene (dfrA1, dfrA5, dfrA7, dfrA12 or dfrA17) was detected in 29/37 (78%) of trimethoprim-resistant isolates tested. This is similar to previous studies that investigated trimethoprim resistance among E. coli isolates and detected dfrA1, dfrA5, dfrA7, dfrA12 and dfrA17 genes in 75–86% of isolates tested [13, 14]. DfrA17 was recently identified as a diagnostically relevant AMR biomarker for trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole resistance through metagenomic screening of over 1000 clinical E. coli isolates [23]. The dfrA genes investigated in this study were not detected in 20 Gram-negative isolates (4 E. coli, 4 Klebsiella pneumoniae and 12 Proteus mirabilis) which were phenotypically resistant to trimethoprim. It is possible that these isolates harbour one or more of the > 30 different dfr genes which have been reported to encode trimethoprim resistance [24] and were not targeted by the PCR assay used in this study.

Nitrofurantoin resistance among E. coli isolates in this study (8.8%) is higher than the 3% reported in the first quarter of 2017 in England [18] and 1.8% in Scotland in 2018 [20] but lower than reports from Wales in 2018 (11%) [21]. Lower resistance levels of E. coli to nitrofurantoin has also been reported in other European countries [25–27], the United States [28], and Australia [29]. While nitrofurantoin resistance is low in the general population, it has been reported to be higher in specific cohorts such as ≥65-year-old males (22.9%) [19]. The higher resistance rates observed in this study may be because urine samples were submitted to the diagnostic laboratory, based on a clinical suspicion of infection. Similar to previous studies [7, 30, 31], this study observed that nitrofurantoin resistance was higher in Klebsiella spp. than in E. coli (see Table S2 in Additional file). This highlights the need for increased surveillance of nitrofurantoin resistance among urinary Klebsiella spp. isolates, especially as prescribing of nitrofurantoin for UTI treatment is increasing [32].

With the exception of a single isolate with an MIC > 32 mg/L, S. saprophyticus isolates in this study were all susceptible to trimethoprim. No dfrA gene was detected in any of the S. saprophyticus isolates tested, although trimethoprim-resistant isolates have been reported in a previous study [33]. Similarly, no dfrA gene was detected by PCR in urine samples containing only Gram-positive organisms, in single and mixed culture. While there is a dfrA gene, which confers trimethoprim resistance in S. saprophyticus and other Staphylococcus spp [33, 34], the gene shares limited homology with the dfrA in Gram-negative bacteria, which may explain why dfrA genes could not be detected in S. saprophyticus isolates and urine in this study.

This study has a number of limitations. Firstly, dfrA genes were used to predict trimethoprim resistance and as some isolates showed phenotypic resistance without detectable dfrA, it is possible that dfrA genes not tested in this study may be encoding trimethoprim resistance in these isolates. Furthermore, this study was limited to E. coli, Klebsiella spp., P. mirabilis and S. saprophyticus. Therefore, further studies would be required to determine whether detection of dfrA genes could predict trimethoprim resistance in less frequently isolated Gram-negative urinary pathogens such Enterobacter spp., Morganella morganii and Providencia spp.

Conclusion

This study showed that the presence of dfrA genes can reliably predict phenotypic trimethoprim resistance in urinary E. coli, Klebsiella spp. and P. mirabilis isolates and in urine without culture. Culture-independent PCR detection of dfrA genes in urine could enable more rapid determination of trimethoprim resistance in urine specimens and guide antibiotic prescribing in patients with a UTI. This could improve antibiotic stewardship and be particularly useful in patients with reduced kidney function where nitrofurantoin use is contra-indicated.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article and its supplementary materials.

Abbreviations

- UTI:

-

Urinary Tract Infection

- HSCT:

-

Health and Social Care Trust

- AST:

-

Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing

- EUCAST:

-

European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing

- MIC:

-

Minimum Inhibitory Concentration

- PCR:

-

Polymerase Chain Reaction

- DEPC:

-

Diethyl pyrocarbonate

References

Pouwels KB, Dolk FCK, Smith DRM, Robotham JV, Smieszek T. Actual versus “ideal” antibiotic prescribing for common conditions in English primary care. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2018;73:19–26.

Dolk FCK, Pouwels KB, Smith DRM, Robotham JV, Smieszek T. Antibiotics in primary care in England: which antibiotics are prescribed and for which conditions? J Antimicrob Chemother. 2018;73:ii2–10.

Devillé WLJM, Yzermans JC, Duijn NP Van, Bezemer D, Windt DAWM Van Der, Bouter LM. The urine dipstick test useful to rule out infections. A meta-analysis of the accuracy. BMC Urol. 2004;4:1–14.

Sundvall PD, Gunnarsson RK. Evaluation of dipstick analysis among elderly residents to detect bacteriuria: a cross-sectional study in 32 nursing homes. BMC Geriatr. 2009;9:32.

Briongos-Figuero LS, Gómez-Traveso T, Bachiller-Luque P, Domínguez-Gil González M, Gómez-Nieto A, Palacios-Martín T, et al. Epidemiology, risk factors and comorbidity for urinary tract infections caused by extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL)-producing enterobacteria. Int J Clin Pract. 2012;66:891–6.

National Institute for health and care excellence. UTI (lower): antimicrobial prescribing. 2018. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng109/resources/visual-summary-pdf-6544021069.

Toner L, Papa N, Aliyu SH, Dev H, Lawrentschuk N, Al-Hayek S. Extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Enterobacteriaceae in hospital urinary tract infections: incidence and antibiotic susceptibility profile over 9 years. World J Urol. 2016;34:1031–7.

Farrell DJ, Morrissey I, de Rubeis D, Robbins M, Felmingham D. A UK multicentre study of the antimicrobial susceptibility of bacterial pathogens causing urinary tract infection. J Infect. 2003;46:94–100.

Rosello A, Hayward AC, Hopkins S, Horner C, Ironmonger D, Hawkey PM, et al. Impact of long-term care facility residence on the antibiotic resistance of urinary tract Escherichia coli and Klebsiella. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2017;72:1184–92.

Kahlmeter G. An international survey of the antimicrobial susceptibility of pathogens from uncomplicated urinary tract infections: the ECO.SENS project. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2003;51:69–76.

Lane DJ. 16S/23S rRNA sequencing. In: Stackebrandt E, Goodfellow M, editors. Nucleic acid techniques in bacterial systematic. New York: Wiley; 1991. p. 115–75.

The European committee on antimicrobial susceptibility testing. Breakpoint tables for interpretation of MICs and zone diameters. Version 9.0. 2019. http://www.eucast.org.

Brolund A, Sundqvist M, Kahlmeter G, Grape M. Molecular characterisation of trimethoprim resistance in Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae during a two year intervention on trimethoprim use. PLoS One. 2010;5:1–5.

Grape M, Motakefi A, Pavuluri S, Kahlmeter G. Standard and real-time multiplex PCR methods for detection of trimethoprim resistance dfr genes in large collections of bacteria. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2007;13:1112–8.

Raz R, Chazan B, Kennes Y, Colodner R, Rottensterich E, Dan M, et al. Empiric use of trimethoprim-Sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX) in the treatment of women with uncomplicated urinary tract infections, in a geographical area with a high prevalence of TMP-SMX–resistant Uropathogens. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:1165–9.

Butler CC, Hillier S, Roberts Z, Dunstan F, Howard A, Palmer S. Antibiotic-resistant infections in primary care are symptomatic for longer and increase workload: outcomes for patients with E. coli UTIs. Br J Gen Pract. 2006;56:686–92.

Duffy AM, Hernandez-Santiago V, Orange G, Davey PG, Guthrie B. Trimethoprim prescription and subsequent resistance in childhood urinary infection: multilevel modelling analysis. Br J Gen Pract. 2013;63:238–43.

Public Health England. English surveillance programme for antimicrobial utilisation and resistance (ESPAUR) 2017. London; 2017.

Public Health England. English surveillance programme for antimicrobial utilisation and resistance (ESPAUR) 2018 to 2019. London; 2019.

Health Protection Scotland. Scottish One Health Antimicrobial Use and Antimicrobial Resistance in 2018. Annu Rep. 2019.

Heginbothom M, Howe R. Antibacterial resistance in urinary coliforms Wales 2009–2018. Public Health Wales; 2019.

Nugent C, Patterson L, Sartaj M. Surveillance of antimicrobial use and resistance in Northern Ireland, Annual Report, 2018. Belfast: Public Health Agency: 2019.

Volz C, Ramoni J, Beisken S, Galata V, Keller A, Plum A, et al. Clinical Resistome screening of 1,110 Escherichia coli isolates efficiently recovers diagnostically relevant antibiotic resistance biomarkers and potential novel resistance mechanisms. Front Microbiol. 2019;10:1671.

Michael GB, Butaye P, Cloeckaert A, Schwarz S. Genes and mutations conferring antimicrobial resistance in Salmonella: an update. Microbes Infect. 2006;8:1898–914.

Haslund JMQ, Rosborg Dinesen M, Sternhagen Nielsen AB, Llor C, Bjerrum L. Different recommendations for empiric first-choice antibiotic treatment of uncomplicated urinary tract infections in Europe. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2013;31:235–40.

Kahlmeter G, Poulsen HO. Antimicrobial susceptibility of Escherichia coli from community-acquired urinary tract infections in Europe: the ECO·SENS study revisited. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2012;39:45–51.

Ny S, Edquist P, Dumpis U, Gröndahl-Yli-Hannuksela K, Hermes J, Kling A-M, et al. Antimicrobial resistance of Escherichia coli isolates from outpatient urinary tract infections in women in six European countries including Russia. J Glob Antimicrob Resist. 2019;17:25–34.

Sanchez GV, Babiker A, Master RN, Luu T, Mathur A, Bordon J. Antibiotic resistance among urinary isolates from female outpatients in the United States in 2003 and 2012. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2016;60:2680–3.

Fasugba O, Das A, Mnatzaganian G, Mitchell BG, Collignon P, Gardner A. Incidence of single-drug resistant, multidrug-resistant and extensively drug-resistant Escherichia coli urinary tract infections: an Australian laboratory-based retrospective study. J Glob Antimicrob Resist. 2019;16:254–9.

Koningstein M, Van Der Bij AK, De Kraker MEA, Monen JC, Muilwijk J, De Greeff SC, et al. Recommendations for the empirical treatment of complicated urinary tract infections using surveillance data on antimicrobial resistance in the Netherlands. PLoS One. 2014;9:e86634.

Magyar A, Köves B, Nagy K, Dobák A, Arthanareeswaran VKA, Bálint P, et al. Spectrum and antibiotic resistance of uropathogens between 2004 and 2015 in a tertiary care hospital in Hungary. J Med Microbiol. 2017;66:788–97.

Public health England PHE. English surveillance Programme for antimicrobial utilisation and resistance (ESPAUR) 2018. London; 2018.

De Sousa VS, Da-Silva APS, Sorenson L, Paschoal RP, Rabello RF, Campana EH, et al. Staphylococcus saprophyticus recovered from humans, food, and recreational waters in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Int J Microbiol. 2017;2017:4287547.

Coelho C, de Lencastre H, Aires-de-Sousa M. Frequent occurrence of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole hetero-resistant Staphylococcus aureus isolates in different African countries. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2017;36:1243–52.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Dr. Ronan McMullan and colleagues in the Routine Diagnostic Laboratories at the Belfast and Northern Health and Social Care Trusts for providing the isolates used in this study.

Funding

This study was supported by a Grant from Invest Northern Ireland and a PhD Studentship from the Department for Employment and Learning (DEL), Northern Ireland and Randox Laboratories Ltd., Northern Ireland to NJ Weir. Randox Laboratories Ltd. provided salary for author MAC but did not have any role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

MAC, CMH, MMT and DFG conceived and designed the study; YMS, NMW and SHP collected samples, performed experiments, analysed, and interpreted the data. YMS drafted the manuscript with substantial revision by MMT and DFG. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval for collection of urine samples was obtained from the South Central - Hampshire B Research Ethics Committee ethical approval (REC Reference: 17/SC/0302). Consent was not required for urine samples as they were surplus samples collected after routine urinalysis.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

MA Crockard was an employee of Randox Laboratories Ltd. (Northern Ireland), a manufacturer of molecular diagnostic tests. All other authors are working in collaboration with Randox Laboratories Ltd. (Northern Ireland).

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Table S1.

Primers used for the detection of dfrA genes.

Additional file 2: Table S2.

Antimicrobial susceptibility of urinary E. coli and Klebsiella spp. isolates. Abbreviations: S: Susceptible; I: Intermediate; R: Resistant. Breakpoints: Amoxicillin (S ≤ 8; R > 8); Ceftazidime (S ≤ 1; I = 1.5 – 4; R > 4); Ciprofloxacin (S ≤ 0.5; I = 0.75 – 1; R > 1); Co-amoxiclav (S ≤ 32; R > 32); Nitrofurantoin (S ≤ 64; R > 64); Trimethoprim (S ≤ 2; I = 3 - 4; R > 4). NA: Not Applicable. Intermediate category not approved for amoxicillin, co-amoxiclav and nitrofurantoin by EUCAST. MIC: minimum inhibitory concentration; MIC50 and MIC90, MICs that inhibit 50% and 90% of the isolates, respectively.

Additional file 3: Table S3.

Microorganisms isolated from clinical urine samples.

Additional file 4: Figure S1.

Gels showing detection of dfrA1 (a), dfrA5 (b), dfrA12 (c) and dfrA7&17 (d) genes.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Somorin, Y.M., Weir, NJ.M., Pattison, S.H. et al. Antimicrobial resistance in urinary pathogens and culture-independent detection of trimethoprim resistance in urine from patients with urinary tract infection. BMC Microbiol 22, 144 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12866-022-02551-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12866-022-02551-9