Abstract

Background

The Sterile Insect Technique (SIT) is being applied for the management of economically important pest fruit flies (Diptera: Tephritidae) in a number of countries worldwide. The success and cost effectiveness of SIT depends upon the ability of mass-reared sterilized male insects to successfully copulate with conspecific wild fertile females when released in the field.

Methods

We conducted a critical analysis of the literature about the tephritid gut microbiome including the advancement of methods for the identification and characterization of microbiota, particularly next generation sequencing, the impacts of irradiation (to induce sterility of flies) and fruit fly rearing, and the use of probiotics to manipulate the fruit fly gut microbiota.

Results

Domestication, mass-rearing, irradiation and handling, as required in SIT, may change the structure of the fruit flies’ gut microbial community compared to that of wild flies under field conditions. Gut microbiota of tephritids are important in their hosts’ development, performance and physiology. Knowledge of how mass-rearing and associated changes of the microbial community impact the functional role of the bacteria and host biology is limited. Probiotics offer potential to encourage a gut microbial community that limits pathogens, and improves the quality of fruit flies.

Conclusions

Advances in technologies used to identify and characterize the gut microbiota will continue to expand our understanding of tephritid gut microbial diversity and community composition. Knowledge about the functions of gut microbes will increase through the use of gnotobiotic models, genome sequencing, metagenomics, metatranscriptomics, metabolomics and metaproteomics. The use of probiotics, or manipulation of the gut microbiota, offers significant opportunities to enhance the production of high quality, performing fruit flies in operational SIT programs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Worldwide, fruit flies (Tephritidae) annually cause substantial damage to horticultural crops, and limit domestic and international trade. Some of the most economically important tephritids include the Mediterranean fruit fly (Ceratitis capitata), oriental fruit fly (Bactrocera dorsalis) and Queensland fruit fly (Bactrocera tryoni). Sterile Insect Technique (SIT) is currently employed in a number of countries to prevent, suppress, contain or eradicate targeted pest species, including tephritid fruit flies [1]. SIT is most successful in an area wide - integrated pest management (AW-IPM) scenario, or geographic isolation [2, 3], and when used in conjunction with other management techniques [4, 5]. The success of SIT depends on irradiated sterile male insects effectively locating, attracting and successfully copulating with wild females [6]. This approach has several advantages including that it is sustainable, has low impact on the environment, does not involve insecticides, and is target-specific.

Fruit fly domestication, irradiation, mass-rearing and handling reduce the fitness, performance and longevity of flies used in SIT programs, thereby reducing the effectiveness of SIT and its cost-benefit ratio [7,8,9]. Behavioural and physiological changes of mass-reared sterile males, such as changes in mating time and duration, ability to join leks, courtship rituals, pheromone production and attractiveness compared to wild fertile males, dramatically affect copulatory success with wild females [8, 10]. Post-mating factors, such as ejaculate transfer and the inability to prevent re-mating, also influence copulatory success [11]. To overcome the typically low copulatory success of sterile males, a larger number of sterile flies are released, relative to the number of wild flies in the field [10, 12], resulting in high mass-rearing costs. Understanding the biology, ecology and behaviour of fruit flies and the effects of domestication, mass-rearing, handling and sterilization of target pest species allows optimization, and improves the cost, efficiency and effectiveness of SIT.

The gut microbiome greatly influences insect health and homeostasis [13, 14]. The symbiotic association of tephritids with bacteria has been recognized for over a century [15], but our appreciation of the importance and complexity of tephritid-microbial symbiont interactions has increased considerably over the last 35 years. Studies removing, or significantly reducing tephritid gut microbiota through antibiotics indicate that microbiota can positively influence various aspects of tephritid biology, such as nitrogen metabolism, longevity, reproduction, fecundity and overcoming phenolic fruit compounds [16,17,18,19,20]. For example, in contrast to antibiotic-fed (asymbiotic) adult olive fly (Bactrocera oleae), untreated flies were able to utilize inaccessible sources of nitrogen, and bacteria assisted in the provision of missing essential nutrients to the host [20]. Offspring of antibiotic-fed field caught B. oleae females failed to complete larval development in unripe olives unlike larvae of untreated females; however, both were able to complete development in ripe olives. Therefore, it was postulated that symbiotic bacteria help overcome the phenolic compounds in unripe olives [19]. A less intuitive example was found for C. capitata. Adults of this species treated with antibiotics and fed a sugar-only adult diet had significantly increased longevity compared with non-antibiotic-treated flies on the same diet; however, the same effects were not seen when the flies were fed a full adult diet (sugar and yeast hydrolysate) [17]. The authors suggested that the antibiotics may be aiding the immune system against non-beneficial gut microbiota of nutritionally stressed flies [17]. Further, an important trait that maintains gut microbiota in flies is their transmission across generations. Female tephritids coat the egg surface with bacteria prior to, or during oviposition, which aids larval development [21,22,23,24,25]. Fitt and O’Brien [26] found surface sterilization of eggs significantly reduced larval weight (3 mg) at 10 days, while larvae from eggs that were not surface sterilized grew normally, weighing about 15 mg. Studies adding symbiotic bacteria to artificial larval diets significantly improved the development and fitness of domesticated fruit flies [26,27,28]. Thus, the tephritid-microbe symbiotic relationships are very intricate and of significant ecological and evolutionary importance. Increasing our knowledge of these relationships may identify ways to enhance performance of insects that are mass- reared for SIT programs.

Our review focuses exclusively on tephritid gut symbionts, excluding intracellular endosymbionts, such as Wolbachia, which may also be detected in insect gut microbiome studies [29]; however, a previous study suggested that fewer tephritid species than expected harbour Wolbachia [30]. While previous review papers have mostly focused on specific tephritid species [31, 32], or progress in understanding the function of tephritid gut microbiota [33, 34], our review examines recent progress on methods and identification of tephritid microbial symbionts, the impact of the domestication process and irradiation on tephritid-microbial symbiont associations and the use of probiotics to manipulate the fruit fly gut microbiota and consequently gut health.

Tephritid gut microbiota

Influence of methodology and sampling design

Current characterization techniques of tephritid gut microbial communities have advantages and limitations. Culture-dependent approaches select for microbes capable of growing under culturing conditions, with a large number of bacterial diversity still unculturable. Molecular methods enable the detection of both culturable and unculturable bacteria, rare bacteria and other difficult to culture microorganisms. Molecular approaches used in tephritid gut microbiome studies have targeted the 16S rRNA gene, and are rapidly expanding our knowledge of tephritid gut bacteria. Indeed, sequencing of 16S rRNA gene amplicons from DNA extracted from oesophageal bulbs of B. oleae, enabled the identification of the unculturable symbiont “Candidatus Erwinia dacicola” [35] that assists larvae developing in unripe olives to overcome the plant’s chemical defense mechanism [19].

Tephritid 16S rRNA gene NGS microbiome studies provide a more comprehensive view of fruit fly gut bacterial communities than earlier methods; however, in general each microbiome study employing NGS needs to be interpreted with some caution [36]. For example, 16S rRNA gene amplicon NGS of wild and laboratory-reared tephritids (larvae and adults) have found up to 24 operational taxonomic units (OTUs) at 97% sequence similarity [19, 20, 22, 37] (Table 1). These studies indicate that the tephritid microbiome is low in diversity, similar to that of Drosophila [43, 44]. However, two studies have reported much higher numbers of OTUs (97% similarity) when studying the gut microbiome of tephritid fruit fly samples; up to 322 OTUs for Bactrocera minax [39] and up to 81 OTUs for B. dorsalis [38] within a life stage time point. These large numbers of OTUs may, for example, be due to the number of samples pooled (50 samples were pooled in Andongma et al. [38]), quality trimming and/or clustering algorithms. Differences also appear to arise based on whether OTUs with low read numbers were discarded. For example Ben-Yosef et al. [19] removed OTUs with less than 10 sequences. No such restrictions were put on the total number of OTUs from various life stages reported in Andongma et al. [38]; however, employing the same criteria would result in a reduction in the total number of OTUs from combined life stages studied from 172 to 42. It is unclear whether OTUs with low read numbers were also removed from Wang et al. [39] and whether possible erroneous OTUs due to sequencing artefacts were removed from the pyrosequencing data; such erroneous OTUs were removed in Morrow et al. [37]. Nonetheless, discounting low prevalence organisms may also be risky, as microbes at low titers may be overlooked [45]. Furthermore, the percentage of sequence similarity used to define OTUs can alter the taxonomic microbiome profile. For example at > 97% similarity, larvae and adult C. capitata shared a dominant OTU, but this was not true when OTUs were called at > 98% similarity [22]. In regard to taxonomic resolution, the region of the 16S rRNA gene sequenced and the length of sequences obtained using NGS technologies is another factor that can confound analyses [46,47,48,49,50]. No two tephritid NGS microbiome studies have followed the same sequencing and analytical approaches (Table 1), which can complicate comparisons between studies, thus clear archiving of sequence data and reporting of downstream processing of the data (e.g. scripts) are critical.

Very few common or ‘core’ bacteria at the genus or species level have been identified in tephritid gut microbiome studies. “Ca. E. dacicola” (Enterobacteriaceae) and Acetobacter tropicalis (Acetobacteraceae) have been identified as prevalent and possible ‘core’ bacteria in B. oleae; however, recent NGS studies of gut microbiota in B. oleae have failed to detect A. tropicalis in the samples analyzed [19, 20], possibly due to sampling of different host populations. The identity of core bacteria has probably also been overlooked as often tephritid gut microbiome studies have only analyzed pooled or small numbers (fewer than seven) individual samples, such as Andongma et al. [38], Morrow et al. [37], Ventura et al. [41], Wang et al. [39], Ben-Yosef et al. [19], Ben-Yosef et al. [20] and Yong et al. [40]. Furthermore, analysis of single pools of samples does not provide any information about diversity within a population. An exception is the C. capitata microbiome study by Malacrinò et al. [42], where 15 or more individuals per life stage were analyzed; however, whether any core bacteria were identified was not discussed. Increased studies on the bacterial diversity within and between populations can provide insight into the environmental influences on tephritids.

Tephritid bacterial communities

To date, the majority of studies investigating tephritid gut bacterial communities have focused on adults. Bacteria of tephritid larvae and changes across tephritid ontogeny have been characterized in few studies [19, 22, 38, 42, 51]. Bacterial complexity is lower at larval and pupal stages, but increases during the adult stage [22, 51], and likely reflects that the larval stage is naturally confined to a single fruit. There does not appear to be major differences in the bacterial classes or families present in the larval and the adult stage [22, 38]; however, relative abundances of bacterial families may shift with development [38]. This suggests that adult flies acquire microbiota in the larval and early teneral stages, although changes between life stages may be more pronounced when looking at the bacterial genus and species levels. Unfortunately, in many studies the short NGS reads combined with the polyphyly of Enterobacteriaceae has limited the resolution of taxa to these levels when analyzing them across developmental stages [22]. Current laboratory-based evidence suggests that once acquired, tephritid gut microbiota may remain relatively stable throughout adult fly development. The same bacterial species were still recoverable from a B. tryoni population 13 days after the bacteria were fed to the flies [52]. Furthermore, fluorescently labelled Enterobacter agglomerans and Klebsiella pneumoniae fed to adult C. capitata remained detectable in three successive generations of adult flies [21].

The majority of bacteria associated with tephritids belong to the phyla Proteobacteria or Firmicutes, with the most abundant and prevalent from only a few families. Studies of culturable and non-culturable bacteria of field collected tephritids revealed that Enterobacteriaceae are dominant in the vast majority of tephritids, including C. capitata [22, 37, 51, 53,54,55,56,57], Anastrepha spp. [41, 58], Bactrocera spp. [23, 26, 35, 37, 39, 40, 52, 59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69], Rhagoletis spp. [70, 71], and others. Further, Enterobacteriaceae dominate the bacteria vertically transferred from adult tephritid females to larvae, via coating of the egg surface with bacteria prior to, or during oviposition [21,22,23,24,25]. Morphological characteristics and behaviour of fruit flies, which contribute to both vertical and horizontal transmission of Enterobacteriaceae, suggests that these bacteria play an important role in fruit fly development and physiology.

Known functions of tephritid gut bacteria within the Enterobacteriaceae family include diazotrophy and pectinolysis [20, 22, 51, 53, 72], and the break-down of chemical host plant defenses [19] and insecticides [73]. However, there does not appear to be a common species or genus within the Enterobacteriaceae family that is consistently found in the studied tephritids or even within a fruit fly species, with the exception of “Ca. E. dacicola”, which is prevalent in all wild B. oleae. This phenotypic plasticity of gut microbiota could indicate that a number of bacteria can perform similar roles, which are conserved at higher taxonomic levels, and are interchangeable, thereby allowing tephritids to adapt to diverse diets, and changing bacterial communities.

Other commonly reported Proteobacteria belong to the families Pseudomonaceae and Acetobacteraceae. Pseudomonaceae are present in a number of tephritid species. For example, Pseudomonas constitutes a minor but stable community within the gut of C. capitata; however, at high densities Pseudomonas aeruginosa significantly reduces C. capitata longevity [54]. Therefore, the role of Pseudomonas spp. in tephritids remains unclear. The acetic acid bacteria A. tropicalis was reported as a major symbiont in B. oleae via a specific end-point PCR, but, as mentioned earlier, has not been detected in B. oleae 16S rRNA gene amplicon NGS studies [19, 20]. Acetobacteraceae have also been reported at low levels in other adult tephritids, but were highly abundant in a single pool of adult female Dirioxa pornia [36], a tephritid species with a particular ecological niche, infesting and developing in damaged and fermenting fallen fruit. Apart from research into A. tropicalis in B. oleae, very little attention has been given to the presence of acetic acid bacteria in tephritids, even though such bacteria are frequently reported as symbionts of insects that have a sugar-based diet within the orders Diptera (including Drosophila fruit fly species), Hymenoptera and Hemiptera [74].

Firmicutes constitute part of the microbiota of most adult Bactrocera spp. studied to date. Bacteria of the order Bacillales have been reported in Bactrocera zonata [68], and in B. oleae [75], and bacteria of the order Lactobacillales have been identified in B. tryoni [37, 64, 65], B. minax [39], Bactrocera cacuminata [64], Bactrocera neohumeralis [37], B. oleae [75] and B. dorsalis [38, 62]. Firmicutes have not frequently been reported for C. capitata, although Leuconostoc were recently detected in the C. capitata NGS microbiome study by Malacrinò et al. [42]. Lactobacillales were more common in laboratory-reared than field collected Bactrocera spp. flies [37]. Most Firmicutes stain Gram positive, and Gram positive bacteria are known to possess a number of mechanisms that increases their survival in acidic environments [76]. This could increase their tolerance of the low pH of larval diets, and, therefore, be carried on to the adult stage. In addition, some lactic acid bacteria are known to produce antimicrobial peptides [77], which may influence the presence of other bacteria in the diet and gut. The function of lactic acid bacteria in tephritids remains unknown.

Fruit fly rearing in an artificial environment impacts on gut microbiota

Fruit flies reared in an artificial environment are not exposed to bacteria typically found in their natural habitat, including microbes that could confer fitness benefits. Artificial tephritid adult diets used for mass-rearing (colony maintenance, not pre-release diets) normally only comprise sugar and yeast hydrolysate; while larval diets typically comprise a bulking agent, yeast, carbohydrates (in the form of sugar or other carbohydrates either added, or within the bulking agent) and antimicrobial agents, such as antifungal and antibacterial agents [78]. While the antimicrobial agents and pH of the larval diet reduce the possibility of contamination with detrimental microorganisms, they may also reduce the opportunities for horizontal transmission of beneficial microbes. Similarly, egg collection methods that rely on water as a transfer medium, and handling methods (e.g. bubbling at temperatures to induce female mortality; required for temperature sensitive lethal strains to produce male only flies under SIT programs), may allow the wider spread of pathogenic bacteria across cultures, and also reduce the vertical transmission of beneficial microorganisms from the adult through to the larval stage.

Consequently, tephritid rearing can change gut microbial communities by reducing bacterial diversity relative to field-collected specimens [19, 24, 37], altering the relative abundance of particular microbes [56] and promoting the acquisition of bacterial species not commonly found in field flies [19, 37]. Mass-reared larvae also have a lower bacterial load than their wild counterparts; larvae from mass-reared olive flies developing in olives have a comparable bacterial load to larvae from field-collected olive flies treated with antibiotics [19]. In addition, olive flies fed an artificial diet have been shown to specifically lack the bacterial symbiont “Ca. E. dacicola”, found in wild flies [59], while artificially reared olive flies fed on olives retain the symbiont [19]. This bacterium allows larvae to develop in unripe olives by counteracting the effects of the phenolic glycoside oleuropein [19]. Although this function is no longer necessary for olive flies not reared on olives, “Ca. E. dacicola” can also accelerate larval development, perhaps through the provision of nitrogen [19]. In contrast, mass-reared adult female olive fly guts were dominated almost exclusively by Providencia spp. [19]. Similarly, while Pseudomonas spp. occur at only low levels in field collected C. capitata (~ 0.005% of total gut bacteria) [54], they can constitute more than 15% of the total gut bacterial population of mass-reared adult Vienna 8 C. capitata [56]. The relative abundance of Enterobacteriaceae in laboratory-reared adult B. tryoni colonies was reduced compared to field collected B. tryoni; however, only three pools of laboratory-reared B. tryoni from different populations were compared to just one pool of field collected B. tryoni, and only females were analyzed [37]. Laboratory rearing also influences the abundance of lactic acid bacteria, such as Lactococcus, Vagococcus and Enterococcus in some Bactrocera laboratory-adapted flies, which do not tend to be present in high densities in wild flies [37].

The gut microbiota of fruit flies also become very similar and ‘streamlined’ when maintained on the same diet within a location. Adult B. tryoni, sourced from different locations maintained on the same larval and adult diets, in the same laboratory, possessed similar microbiota [37]. Indeed, similar bacteria were also identified from B. neohumeralis laboratory-adapted colonies, which were established 3 years apart but reared within the same facility [37]. Interestingly, the gut microbiome profile of B. neohumeralis differed between populations reared in different laboratories, suggesting an environmental influence on the bacteria associated with artificially reared-adult fruit flies. Identifying the factors driving changes in tephritid gut microbiota, such as age, diet, environment and genetics, is important to identify ways to minimise, or even avoid, unwanted microbial changes, and optimise the gut ecology of mass-reared tephritids.

When domesticated flies are stressed due to nutrition, overcrowding, increased waste products, exposure to larger densities of particular bacteria and genetic changes, this could influence fly susceptibility to pathogens. For example, Serratia marcescens is pathogenic to Rhagoletis pomonella [79] and to Drosophila melanogaster [80, 81]. Lloyd et al. [69] found that Enterobacteriaceae, such as Klebsiella, Erwinia and Enterobacter, were frequently cultured from field collected B. tryoni, while S. marcescens and Serratia liquefaciens were dominant in laboratory flies, which may have been introduced by D. melanogaster flies frequently found around laboratory-reared tephritid colonies. Mortality of Bactrocera jarvisi larvae feeding on a carrot diet at neutral pH spiked with S. liquefaciens, suggests that this bacterium can be pathogenic [26]. In a recent study, Serratia spp. were shown to dominate (> 90%) a laboratory-adapted B. cacuminata colony, relative to a wild population, which was dominated (> 90%) by Enterobacter spp. [37]. In the same laboratory, > 60% of the bacteria within laboratory-adapted B. jarvisi comprised of Serratia spp. [37]. These organisms were also detected (but were not dominant) in laboratory-adapted B. tryoni sourced from different populations, but formed only a very minor constituent of field-caught B. tryoni [37]. Further work is required to determine whether the genus Serratia, members of this genus, or relative amounts of Serratia are pathogenic to tephritids fed artificial diets, or whether it is the loss of important endosymbionts as a result of the presence of Serratia that negatively impacts the host. This also highlights the need to better understand the interplay between tephritid microbes.

Good sanitary procedures within a mass-rearing facility are essential. Many aspects of the mass-rearing environment, such as communal feeding, encourage the spread of pathogens, which could be bacterial, viral, fungal or protozoan. Within a laboratory setting, bacteria can spread from adjacent cages within days, to several meters within a few weeks [72]. They could also be spread through equipment and staff maintaining fly colonies. However, it is not just pathogenic bacteria that can be harmful to fruit fly rearing efforts, but also the presence of unwanted microbes in the diet that could deplete nutrients, increase fermentation within the diet, or produce metabolic wastes that are harmful or repulsive to fruit flies [78]. Such effects add to the stress of rearing, which in turn may increase susceptibility to pathogens [82]. Furthermore, some microbial contaminants could be harmful to production facility staff, farmers and in the end consumers when the flies are released, plus the plants the flies come into contact with as fruit flies are capable of spreading bacteria in the field [83]. However, maintenance of beneficial gut bacteria of flies through dietary and environmental manipulation, or the use of probiotic diet supplements to encourage beneficial microbes, and restrict pathogens or contaminants in the fruit fly diet are areas of research that demonstrate great potential.

The general hypothesis is that microbial diversity contributes to healthier flies and that observed taxonomic differences in artificially reared flies result in less resilience and increased sensitivity to environmental changes due to decreased bacterial diversity and perhaps decreased functional diversity. Little is known about the relationship between the structure of fruit fly bacterial communities and functional diversity and the impact of taxonomic differences at the functional level. Analytical approaches such as metagenomics, metatranscriptomics, metabolomics and metaproteomics will facilitate significant progress in this area as they will permit better characterization of microbial communities, their function and contribution to host development, fitness and performance.

Effect of irradiation

Fruit flies to be released in SIT operations are typically sterilized as pupae using gamma irradiation [84]. Lauzon and Potter’s [85] comparison of irradiated versus non-irradiated C. capitata and A. ludens midguts using electron microscopy showed that irradiation has an effect on both the gut microbiota and the development of the midgut epithelium. Transmission electron microscope images revealed that bacteria in two-day old flies irradiated as pupae appeared to be irregular in shape and lacked fimbriae, while the bacteria in non-irradiated two-day old flies attached to the peritrophic membrane using fimbriae. Irradiation also had an effect on peritrophic membrane development, which appeared to be irregular and gel-like in two-day old irradiated flies, while it was well developed in two-day old non-irradiated flies [85]. It is not yet known whether this tissue and bacterial cell damage was long-lasting and warrants further investigation. Damage to the gut epithelium may not only have an effect on the gut bacterial population, but may consequently also affect nutrient absorption. Although the gut bacterial community structure was different in newly eclosed irradiated compared to non-irradiated mass-reared Vienna 8 C. capitata, after 5 days the gut community resembled the gut community of non-irradiated flies at eclosion [56]. This difference at emergence could reflect a change in nutrient availability and uptake to an irradiated fly during the first few days after eclosion. The study by Lauzon et al. [21] demonstrated that irradiation does not appear to disrupt the vertical transmission of E. agglomerans and K. pneumoniae, originally coated onto fruit fly eggs, to adult C. capitata guts and it is currently unclear how irradiation actually induces a shift in gut bacterial community. However, we can hypothesize that damage caused by irradiation to the gut epithelium and bacteria, in addition to the associated stress, can influence the gut bacterial community. In Drosophila gut microbes stimulate intestinal stem cell activity, which can renew the gut epithelium [86]. As gut bacteria influence epithelial metabolism and cell proliferation through the production of short chain fatty acids, such as acetate, butyrate and propionate [87, 88], greater knowledge of this in tephritids may identify ways to improve the ability of mass-reared flies to recover from irradiation.

Potential of probiotics to improve tephritid performance

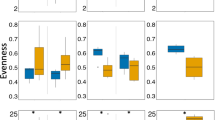

Probiotics, by definition, refers to products that contain a sufficient number of live microorganisms that confer a discernible health benefit on the host [89]. Drew et al. [90] conducted one of the first studies demonstrating that bacteria are a food source and provide nutrients to fruit flies, which, in turn, can positively influence egg production and longevity. Since then, over ten studies [26,27,28, 56, 72, 91,92,93,94,95,96] have investigated the effect of bacterial supplements, more recently referred to as probiotics, added to tephritid diets, on the host, with mixed results. Substantial changes are not always observed (discussed below); however, the majority of the changes recorded positive outcomes for the host (Fig. 1). Measurements of tephritid fruit fly fitness and performance following administration of probiotics mostly focus on immediate benefits. Therefore, it is possible that other impacts, such as changes in the expression of host immune response genes, and genes involved in signalling and/or metabolism, have been overlooked. Negative impacts have been observed in probiotic fed adult B. oleae, where a reduction in longevity has been observed; however, whether this appears to be influenced by the diet the adult flies are feeding on (i.e. sugar versus sugar and protein diet) or the bacteria remains unclear [99]. The bacterial species fed to the adult fly can also influence longevity [90]. Thus, benefits provided by probiotics are not always consistent between studies, most likely due to the complexity of tephritid-bacteria interactions. Further, other factors are likely to influence results including variations in experimental design, probiotic supplements tested and their delivery (dose, mode), experimental conditions, traits measured on varying life stages, irradiated or non-irradiated flies, pre-existing microbiota in experimental flies, diet (nutritional value, antimicrobials, agar versus granular), rearing environment, age and genetic diversity of experimental colonies. As the wild tephritid gut microbiome is often comprised of diverse microbiota, it is feasible that the addition of more than one probiotic candidate, i.e. bacterial blends/consortiums, to domesticated tephritids may provide increased or even additional benefits. Therefore, any probiotic study needs to be well replicated, or a sufficient number of samples included due to the complexity of such studies. In addition, any trade-offs (if observed) need to be assessed, for example, against improved mating performance, as to their importance in SIT effectiveness.

Tephritid life stages, the effects of mass-rearing on the gut microbiome, and the benefits of probiotic applications to the diet. a Larval stage with representation of the bacterial gut microbiome; b pupal stage, which is treated with gamma irradiation for the sterile insect technique (SIT); c adult and egg stages with representation of the adult gut microbiome. Larval and pupal illustrations adapted from Hely et al. [97] and adult illustration adapted from the Australian Insect Names Website by the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation and Department of Agriculture and Fisheries [98]

The addition of symbiotic bacteria to the larval and adult fruit fly diets changes the structure of fruit fly gut bacterial communities (Fig. 1). Indeed, adding a probiotic supplement cocktail containing Klebsiella pneumoniae, Enterobacter sp. and Citrobacter freundii to the C. capitata larval diet simultaneously increased the number of Enterobacteriaceae in the larval and adult gut and reduced the number of Pseudomonas spp. present at both the larval and adult stages [27]. Similarly, feeding Klebsiella oxytoca to adult Vienna 8 strain C. capitata increased the abundance of K. oxytoca in the gut, and reduced the number of Pseudomonas, Morganella and Providencia spp. [56]. It is hypothesized that the gut Enterobacteriaceae community of C. capitata can control the density of bacteria that are harmful in high abundance, such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa [54].

The majority of tephritid probiotic studies have involved the addition of bacteria to the adult diet, and while, the observed impacts on the host have been variable, the positive impacts are encouraging for their potential application in SIT programs (Fig. 1). Sterile male C. capitata fed a sugar diet enriched with K. oxytoca compared to flies fed a sugar only diet, showed increased mating competitiveness in both laboratory and field cages, reduced female remating (presumably in a laboratory setting), and increased survival under starvation in the laboratory [92]. Similarly, a mating advantage was conferred in laboratory studies of C. capitata fed Enterobacter agglomerans and K. pneumoniae in a yeast-enhanced agar compared to non-bacterial inoculated yeast-enhanced agar, but no significant effect was observed with a sugar-yeast or sugar-reduced yeast granular diet [94]. Conversely, mating competitiveness studies in field cages only found significantly more matings (with wild/F1-F15 laboratory-reared flies) than the control when the flies were fed yeast-reduced sugar granulate diet [94]. While mating was not assessed, Meats et al. [93] detected no evidence of either, K. oxytoca or K. pneumoniae added to the adult B. tryoni diet (paste of sugar and autolysed yeast) impacting on egg production regardless of whether the fly generation was F0-F20; however, as expected (presumably due to laboratory adaptation) regardless of bacterial supplementation, egg production increased as the fly generation increased. The addition of Pseudomonas putida to the sugar diet of B. oleae increased female fecundity compared to females fed a sugar only diet [99]. However, P. putida added to a complete diet (comprising of sugar and hydrolysed brewer’s yeast) had no significant effect on fecundity compared to the same diet without added P. putida [99]. These studies indicate that bacteria contribute to fly nutrition, although not exclusively (see next paragraph). It is possible that when the flies are provided with a nutritionally balanced diet, i.e. the amount of yeast, providing fatty acids, amino acids and vitamins, is adequate, the effect of a probiotic supplement is minimal, but this would be dependent on the influence of nutrition on the trait being measured. Thus, the role of the gut microbiome may have largely been underestimated in nutritional studies, and it is possible that through adding bacterial supplements to the fruit fly diet, the amount of yeast required could be reduced. Further, other components of the gut microbiome, such as yeasts, which can also contribute to the host nutrition, have largely been overlooked until recently [100].

Several studies have investigated the impact of feeding autoclaved bacteria, which by definition are not classed as a probiotic, to tephritids [28, 56, 92]. Autoclaved Enterobacter sp. added to the C. capitata larval diet significantly reduced egg to adult developmental time [28]. This study suggests that bacterial mass and/or bacterial substrates can have a positive nutritional effect on immature C. capitata. However, studies comparing the use of autoclaved bacteria to live bacteria show that the contribution of live bacteria to the host is greater than just the nutritional value of dead bacteria themselves and what they produce in culture. The addition of autoclaved K. oxytoca to the C. capitata adult pre-release sugar/sucrose only diet did not improve mating performance [92] or mating latency [56], in contrast to a diet supplemented with live K. oxytoca. The nutritional benefits observed when using an autoclaved, or live culture may be due to metabolites produced by the bacteria; it is not known what metabolites are being produced by tephritid gut bacteria and what effect they have on the gut microbiome and the host. In Drosophila, the metabolite acetate, a product of pyrroloquinoline quinone–dependent alcohol dehydrogenase (PQQ-ADH) by the commensal gut bacterium, Acetobacter pomorum, modulates insulin/insulin-like growth factor signalling, which is important for normal larval development [101]. Gut microbiota and their metabolites will be an exciting area of research to follow in the future, particularly with the development of tools such as metabolomics.

Although only a few studies have investigated the effects of adding probiotic supplements to the larval diet, the results have revealed a number of benefits. Addition of Enterobacter spp., K. pneumoniae and C. freundii to the wheat bran larval diet increased pupal weight of C. capitata Vienna 8 genetic sexing strain (GSS), fly size, spermatozoa storage in females, and also improved aspects of mating competitiveness of sterile flies in laboratory settings [27]. The addition of an Enterobacter sp. to the larval carrot-based diet improved egg-pupal and egg-adult recovery of C. capitata Vienna 8 GSS, and reduced the duration of the egg-pupal, pupal and egg-adult stages [28]. Reduced developmental time is a considerable advantage in mass-rearing facilities leading to cost savings and increased production. The benefits observed at the larval stage could have flow-on effects to the pupae and to adult morphology, fitness and performance. Thus, there is a need to increase our understanding of the influence of each life stage on successive stages and generations, particularly considering the vertical transmission of microbiota.

The presence of beneficial microbes in the larval diet may allow a reduction in the added amount of antimicrobials. Some yeasts possess antagonistic properties against undesirable bacteria [102]. Four studies have cultured yeasts from field collected tephritid fruit fly larvae (B. tryoni and Anastrepha mucronota) indicating that they consume yeasts while feeding within fruit [100, 103,104,105]. Thus, the incorporation of live yeasts, rather than pasteurized yeasts, for example, into the larval diet may be a way to reduce the amount of antimicrobials in the diet and warrants further testing. The interaction between bacteria and yeasts in the gut is an unexplored area in tephritid fruit fly research.

The development of a tephritid gnotobiotic model system that allows the addition and manipulation of flies, which have either developed under axenic conditions, or for which all present microbiota are known, would enable the better examination and verification of host-microbe relationships. Surface sterilization of eggs would remove the transmission of gut microbiota transferred with the egg during oviposition, and the larvae that emerge can then be used in an axenic system. This would help avoid non-microbial effects that could derive from the use of antibiotics, such as effects on mitochondrial respiration [106].

Conclusion

While significant progress has been made towards the taxonomic characterisation and profiling of gut microbial populations in tephritids, there are still considerable gaps in our knowledge of tephritid-bacteria interactions. Improvements in NGS technologies and bioinformatics, in combination with decreased costs, will improve our knowledge of gut microbial diversity and potentially identify further key bacterial and other microbial symbionts. However, the largest unknown factors remain with the functional roles of the microbial symbionts. Use of gnotobiotic models, genome sequencing, metagenomics, metatranscriptomics, metabolomics and metaproteomics will help in defining precise roles of gut microbes. To maintain tephritid-microbial symbiont interactions during the mass-rearing process, we need to understand how such interactions evolve and how both irradiation [107] and the domestication process [108], including diet, disrupts the relationship and associated bacterial functions. This will inform the development of ways to encourage, maintain or introduce symbiotic microbes in the rearing process to produce better performing, and cost-effective flies for SIT programs. Microbial symbionts, whether through the administration of larval and/or adult probiotics, or the maintenance of a healthy gut microbiome through dietary and environmental manipulation, may well be the next major improvement to fruit fly mass-rearing.

Availability of data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- AW-IPM:

-

Area wide - integrated pest management

- GSS:

-

Genetic sexing strain

- NGS:

-

Next-generation sequencing

- OTU:

-

Operational taxonomic unit

- PQQ-ADH:

-

Pyrroloquinoline quinone–dependent alcohol dehydrogenase

- SIT:

-

Sterile insect technique

References

Hendrichs J, Vreysen MJB, Enkerlin WR, Cayol JP. Strategic Options in Using Sterile Insects for Area-Wide Integrated Pest Management. In: Dyck VA, Hendrichs J, Robinson AS, editors. Sterile Insect Technique: Principles and Practice in Area-Wide Integrated Pest Management. Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands; 2005. p. 563–600.

Barnes BN, Hofmeyr JH, Groenewald S, Conlong DE, Wohlfarter M. The sterile insect technique in agricultural crops in South Africa: a metamorphosis .... but will it fly? Afr Entomol. 2015;23:1–18.

Enkerlin W, Gutierrez-Ruelas JM, Cortes AV, Roldan EC, Midgarden D, Lira E, Lopez JLZ, Hendrichs J, Liedo P, Arriaga FJT. Area freedom in Mexico from Mediterranean fruit fly (Diptera: Tephritidae): a review of over 30 years of a successful containment program using an integrated area-wide SIT approach. Fla Entomol. 2015;98:665–81.

Gurr GM, Kvedaras OL. Synergizing biological control: Scope for sterile insect technique, induced plant defences and cultural techniques to enhance natural enemy impact. Biol Control. 2010;52:198–207.

Vargas RI, Mau RFL, Jang EB, Faust RM, Wong L. The Hawaii Fruit Fly Area-Wide Pest Management Program. In: Cuperus GW, Elliott NC, editors. Areawide IPM: theory to implementation Koul O. London: CABI Books; 2008. p. 300–25.

Calkins CO, Parker AG. Sterile Insect Quality. In: Dyck VA, Hendrichs J, Robinson AS, editors. Sterile Insect Technique: Principles and Practice in Area-Wide Integrated Pest Management. Dordrecht: Springer; 2005. p. 269–96.

Liimatainen J, Hoikkala A, Shelly T. Courtship behavior in Ceratitis capitata (Diptera : Tephritidae): Comparison of wild and mass-reared males. Ann Entomol Soc Am. 1997;90:836–43.

Hendrichs J, Robinson AS, Cayol JP, Enkerlin W. Medfly area wide sterile insect technique programmes for prevention, suppression or eradication: The importance of mating behavior studies. Fla Entomol. 2002;85:1–13.

Shelly TE, Whittier TS. Mating competitiveness of sterile male Mediterranean fruit flies (Diptera: Tephritidae) in male-only releases. Ann Entomol Soc Am. 1996;89:754–8.

Lance DR, McInnispp DO. Biological basis of the sterile insect technique. In: Dyck A, Hendrichs J, Robinson AS, editors. Sterile insect technique: Principles and practice in area-wide integrated pest management. Dordrecht: Springer; 2005. p. 69–994.

Pérez-Staples D, Shelly TE, Yuval B. Female mating failure and the failure of ‘mating’ in sterile insect programs. Entomol Exp Appl. 2013;146:66–78.

Shelly T, McInnis D. Sterile insect technique and control of tephritid fruit flies: Do species with complex courtship require higher overflooding ratios? Ann Entomol Soc Am. 2016;109:1–11.

Engel P, Moran NA. The gut microbiota of insects - diversity in structure and function. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2013;37:699–735.

Dillon RJ, Dillon VM. The gut bacteria of insects: Nonpathogenic interactions. Annu Rev Entomol. 2004;49:71–92.

Petri L. Ricerche Sopra i Batteri Intestinali Della Mosca Olearia. Roma, Italy; 1909.

Ben-Yosef M, Aharon Y, Jurkevitch E, Yuval B. Give us the tools and we will do the job: symbiotic bacteria affect olive fly fitness in a diet-dependent fashion. Proc R Soc B-Biol Sci. 2010;277:1545–52.

Ben-Yosef M, Behar A, Jurkevitch E, Yuval B. Bacteria-diet interactions affect longevity in the medfly - Ceratitis capitata. J Appl Entomol. 2008;132:690–4.

Ben-Yosef M, Jurkevitch E, Yuval B. Effect of bacteria on nutritional status and reproductive success of the Mediterranean fruit fly Ceratitis capitata. Physiol Entomol. 2008;33:145–54.

Ben-Yosef M, Pasternak Z, Jurkevitch E, Yuval B. Symbiotic bacteria enable olive fly larvae to overcome host defences. R Soc Open Sci. 2015;2:150170.

Ben-Yosef M, Pasternak Z, Jurkevitch E, Yuval B. Symbiotic bacteria enable olive flies (Bactrocera oleae) to exploit intractable sources of nitrogen. J Evol Biol. 2014;27:2695–705.

Lauzon CR, McCombs SD, Potter SE, Peabody NC. Establishment and vertical passage of Enterobacter (Pantoea) agglomerans and Klebsiella pneumoniae through all life stages of the Mediterranean fruit fly (Diptera: Tephritidae). Ann Entomol Soc Am. 2009;102:85–95.

Aharon Y, Pasternak Z, Ben Yosef M, Behar A, Lauzon C, Yuval B, Jurkevitch E. Phylogenetic, metabolic, and taxonomic diversities shape Mediterranean fruit fly microbiotas during ontogeny. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2013;79:303–13.

Sacchetti P, Granchietti A, Landini S, Viti C, Giovannetti L, Belcari A. Relationships between the olive fly and bacteria. J Appl Entomol. 2008;132:682–9.

Estes AM, Hearn DJ, Bronstein JL, Pierson EA. The olive fly endosymbiont, "Candidatus Erwinia dacicola", switches from an intracellular existence to an extracellular existence during host insect development. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2009;75:7097–106.

Courtice AC, Drew RAI. Bacterial regulation of abundance in tropical fruit flies (Diptera: Tephritidae). Aust J Zool. 1984;21:251–68.

Fitt GP, O'Brien RW. Bacteria associated with four species of Dacus (Diptera: Tephritidae) and their role in the nutrition of the larvae. Oecologia (Berlin). 1985;67:447–54.

Hamden H, Guerfali MM, Fadhl S, Saidi M, Chevrier C. Fitness improvement of mass-reared sterile males of Ceratitis capitata (Vienna 8 strain) (Diptera: Tephritidae) after gut enrichment with probiotics. J Econ Entomol. 2013;106:641–7.

Augustinos AA, Kyritsis GA, Papadopoulos NT, Abd-Alla AMM, Cáceres C, Bourtzis K. Exploitation of the medfly gut microbiota for the enhancement of sterile insect technique: use of Enterobacter sp. in larval diet-based probiotic applications. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0136459. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0136459.

Yun JH, Roh SW, Whon TW, Jung MJ, Kim MS, Park DS, Yoon C, Nam YD, Kim YJ, Choi JH, et al. Insect gut bacterial diversity determined by environmental habitat, diet, developmental stage, and phylogeny of host. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2014;80:5254–64.

Morrow JL, Frommer M, Royer JE, Shearman DCA, Riegler M. Wolbachia pseudogenes and low prevalence infections in tropical but not temperate Australian tephritid fruit flies: manifestations of lateral gene transfer and endosymbiont spillover? BMC Evol Biol. 2015;15:202. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12862-015-0474-2.

Behar A, Ben-Yosef M, Lauzon CR, Yuval B, Jurkevich E. Structure and function of the bacterial community associated with the Mediterranean fruit fly. In: Bourtzis K, Miller TA, editors. Insect Symbiosis. 3rd ed. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2009. p. 251–71.

Yuval B, Ben-Ami E, Behar A, Ben-Yosef M, Jurkevitch E. The Mediterranean fruit fly and its bacteria - potential for improving sterile insect technique operations. J Appl Entomol. 2013;137:39–42.

Jurkevitch E. Evolution and Consequences of Nutrition-Based Symbioses in Insects: More than Food Stress. In: Seckbach J, Grube M, editors. Symbioses and Stress: Joint Ventures in Biology. Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht; 2010. p. 265–88.

Drew RAI, Lloyd AC. Bacteria in the life cycle of tephritid fruit flies. In: Barbosa P, Krischik VA, Jones CG, editors. Microbial Mediation of Plant-Herbivore Interactions. New York: Wiley; 1991. p. 441–66.

Capuzzo C, Firrao G, Mazzon L, Squartini A, Girolami V. 'Candidatus Erwinia dacicola', a coevolved symbiotic bacterium of the olive fly Bactrocera oleae (Gmelin). Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2005;55:1641–7.

Goodrich JK, Di Rienzi SC, Poole AC, Koren O, Walters WA, Caporaso JG, Knight R, Ley RE. Conducting a microbiome study. Cell. 2014;158:250–62.

Morrow JL, Frommer M, Shearman DC, Riegler M. The Microbiome of field-caught and laboratory-adapted Australian tephritid fruit fly species with different host plant use and specialisation. Microb Ecol. 2015;70:498–508.

Andongma AA, Wan L, Dong Y-C, Li P, Desneux N, White JA, Niu C-Y. Pyrosequencing reveals a shift in symbiotic bacteria populations across life stages of Bactrocera dorsalis. Sci Rep. 2015;5:9470. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep09470.

Wang A, Yao Z, Zheng W, Zhang H. Bacterial communities in the gut and reproductive organs of Bactrocera minax (Diptera: Tephritidae) based on 454 pyrosequencing. PLoS One. 2014;9:e106988. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0106988.

Yong HS, Song SL, Chua KO, Lim PE. Microbiota associated with Bactrocera carambolae and B. dorsalis (Insecta: Tephritidae) revealed by next-generation sequencing of 16S rRNA gene. Meta Gene. 2017;11:189–96.

Ventura C, Briones-Roblero CI, Hernández E, Rivera-Orduña FN, Zúñiga G. Comparative analysis of the gut bacterial community of four Anastrepha fruit flies (Diptera: Tephritidae) based on pyrosequencing. Curr Microbiol. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00284-018-1473-5.

Malacrinò A, Campolo O, Medina RF, Palmeri V. Instar- and host-associated differentiation of bacterial communities in the Mediterranean fruit fly Ceratitis capitata. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0194131. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0194131.

Wong CNA, Ng P, Douglas AE. Low-diversity bacterial community in the gut of the fruitfly Drosophila melanogaster. Environ Microbiol. 2011;13:1889–900.

Chandler JA, Lang JM, Bhatnagar S, Eisen JA, Kopp A. Bacterial communities of diverse Drosophila species: ecological context of a host-microbe model system. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1002272. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgen.1002272.

Glassing A, Dowd SE, Galandiuk S, Davis B, Chiodini RJ. Inherent bacterial DNA contamination of extraction and sequencing reagents may affect interpretation of microbiota in low bacterial biomass samples. Gut Pathog. 2016;8:24. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13099-016-0103-7.

Schloss PD, Jenior ML, Koumpouras CC, Westcott SL, Highlander SK. Sequencing 16S rRNA gene fragments using the PacBio SMRT DNA sequencing system. PeerJ. 2016;4. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.1869.

Wang Q, Garrity GM, Tiedje JM, Cole JR. Naive Bayesian classifier for rapid assignment of rRNA sequences into the new bacterial taxonomy. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73:5261–7.

Hiergeist A, Glaesner J, Reischl U, Gessner A. Analyses of intestinal microbiota: Culture versus sequencing. ILAR. 2015;56:228–40.

Yarza P, Yilmaz P, Pruesse E, Gloeckner FO, Ludwig W, Schleifer K-H, Whitman WB, Euzeby J, Amann R, Rossello-Mora R. Uniting the classification of cultured and uncultured bacteria and archaea using 16S rRNA gene sequences. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2014;12:635–45.

Kim M, Morrison M, Yu Z. Evaluation of different partial 16S rRNA gene sequence regions for phylogenetic analysis of microbiomes. J Microbiol Methods. 2011;84:81–7.

Behar A, Jurkevitch E, Yuval B. Bringing back the fruit into fruit fly-bacteria interactions. Mol Ecol. 2008;17:1375–86.

Drew RAI, Lloyd AC. Relationship of fruit flies (Diptera: Tephritidae) and their bacteria to host plants. Ann Entomol Soc Am. 1987;80:629–36.

Behar A, Yuval B, Jurkevitch E. Enterobacteria-mediated nitrogen fixation in natural populations of the fruit fly Ceratitis capitata. Mol Ecol. 2005;14:2637–43.

Behar A, Yuval B, Jurkevitch E. Gut bacterial communities in the Mediterranean fruit fly (Ceratitis capitata) and their impact on host longevity. J Insect Physiol. 2008;54:1377–83.

Behar A, Yuval B, Jurkevitch E. Community structure of the Mediterranean fruit fly microbiota: Seasonal and spatial sources of variation. Isr J Ecol Evol. 2008;54:181–91.

Ben-Ami E, Yuval B, Jurkevitch E. Manipulation of the microbiota of mass-reared Mediterranean fruit flies Ceratitis capitata (Diptera: Tephritidae) improves sterile male sexual performance. ISME J. 2010;4:28–37.

Marchini D, Marri L, Rosetto M, Manetti AGO, Dallai R. Presence of antibacterial peptides on the laid egg chorion of the medfly Ceratitis capitata. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;240:657–63.

Kuzina LV, Peloquin JJ, Vacek DC, Miler TA. Isolation and identification of bacteria associated with adult laboratory Mexican fruit flies, Anastrepha ludens (Diptera : Tephritidae). Curr Microbiol. 2001;42:290–4.

Estes AM, Hearn DJ, Burrack HJ, Rempoulakis P, Pierson EA. Prevalence of Candidatus Erwinia dacicola in wild and laboratory olive fruit fly populations and across developmental stages. Environ Entomol. 2012;41:265–74.

Kounatidis I, Crotti E, Sapountzis P, Sacchi L, Rizzi A, Chouaia B, Bandi C, Alma A, Daffonchio D, Mavragani-Tsipidou P, et al. Acetobacter tropicalis is a major symbiont of the Olive Fruit Fly (Bactrocera oleae). Appl Environ Microbiol. 2009;75:3281–8.

Tsiropoulos GJ. Microflora associated with wild and laboratory reared adult olive fruit flies, Dacus oleae (Gmel). Z Angew Entomol. 1983;96:337–40.

Liu LJ, Martinez-Sañudo I, Mazzon L, Prabhakar CS, Girolami V, Deng YL, Dai Y, Li ZH. Bacterial communities associated with invasive populations of Bactrocera dorsalis (Diptera: Tephritidae) in China. Bull Entomol Res. 2016;106:718–28.

Thaochan N, Sittichaya W, Sausa-ard W, Chinajariyawong A. Incidence of Enterobacteriaceae in the larvae of the polyphagous insect Bactrocera papayae Drew & Hancock (Diptera: Tephritidae) infesting different host fruits. Philipp Agric Sci. 2013;96:384–91.

Thaochan N, Drew RAI, Chinajariyawong A, Sunpapao A, Pornsuriya C. Gut bacterial community structure of two Australian tropical fruit fly species (Diptera: Tephritidae). Songklanakarin J Sci Technol. 2015;37:617–24.

Thaochan N, Drew RAI, Hughes JM, Vijaysegaran S, Chinajariyawong A. Alimentary tract bacteria isolated and identified with API-20E and molecular cloning techniques from Australian tropical fruit flies, Bactrocera cacuminata and B tryoni. J Insect Sci. 2010;10:131. https://doi.org/10.1673/031.010.13101.

Hadapad AB, Prabhakar CS, Chandekar SC, Tripathi J, Hire RS. Diversity of bacterial communities in the midgut of Bactrocera cucurbitae (Diptera: Tephritidae) populations and their potential use as attractants. Pest Manag Sci. 2016;72:1222–30.

Khan M, Mahin AA, Pramanik MK, Akter H. Identification of gut bacterial community and their effect on the fecundity of pumpkin fly, Bactrocera tau (Walker). J Entomol. 2014;11:68–77.

Reddy K, Sharma K, Singh S. Attractancy potential of culturable bacteria from the gut of peach fruit fly, Bactrocera zonata (Saunders). Phytoparasitica. 2014;42:691–8.

Lloyd AC, Drew RAI, Teakle DS, Hayward AC. Bacteria associated with some Dacus species (Diptera, Tephritidae) and their host fruit in Queensland. Aust J Biol Sci. 1986;39:361–8.

Howard DJ, Bush GL, Breznak JA. The evolutionary significance of bacteria associated with Rhagoletis. Evolution. 1985;39:405–17.

Rossiter MC, Howard DJ, Bush GL. Symbiotic bacteria of Rhagoletis pomonella. In: Fruit Flies of Economic Importance, Proceedings of the CEC/IOBC Symposium November 1982; Athens. Rotterdam: A. A. Balkema. p. 77–84.

Murphy KM, Teakle DS, Macrae IC. Kinetics of colonization of adult Queensland fruit flies (Bactrocera tryoni) by dinitrogen-fixing alimentary tract bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1994;60:2508–17.

Cheng D, Guo Z, Riegler M, Xi Z, Liang G, Xu Y. Gut symbiont enhances insecticide resistance in a significant pest, the oriental fruit fly Bactrocera dorsalis (Hendel). Microbiome. 2017;5:13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40168-017-0236-z.

Crotti E, Rizzi A, Chouaia B, Ricci I, Favia G, Alma A, Sacchi L, Bourtzis K, Mandrioli M, Cherif A, et al. Acetic acid bacteria, newly emerging symbionts of insects. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2010;76:6963–70.

Estes AM, Nestel D, Belcari A, Jessup A, Rempoulakis P, Economopoulos AP. A basis for the renewal of sterile insect technique for the olive fly, Bactrocera oleae (Rossi). J Appl Entomol. 2012;136:1–16.

Cotter PD, Hill C. Surviving the acid test: Responses of Gram-positive bacteria to low pH. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2003;67:429–53.

Hassan M, Kjos M, Nes IF, Diep DB, Lotfipour F. Natural antimicrobial peptides from bacteria: characteristics and potential applications to fight against antibiotic resistance. J Appl Microbiol. 2012;113:723–36.

Cohen AC. Microbes in the Diet Setting. 2nd ed. Boca Raton: CRC Press; 2015.

Lauzon CR, Bussert TG, Sjogren RE, Prokopy RJ. Serratia marcescens as a bacterial pathogen of Rhagoletis pomonella flies (Diptera : Tephritidae). Eur J Entomol. 2003;100:87–92.

Lemaitre B, Hoffmann J. The host defense of Drosophila melanogaster. Annu Rev Immunol. 2007;25:697–743.

Nehme NT, Liegeois S, Kele B, Giammarinaro P, Pradel E, Hoffmann JA, Ewbank JJ, Ferrandon D. A model of bacterial intestinal infections in Drosophila melanogaster. PLoS Path. 2007;3:1694–709.

Tanada Y, Kaya HK. Insect Pathology San Diego: Academic Press; 1993.

Sela S, Nestel D, Pinto R, Nemny-Lavy E, Bar-Joseph M. Mediterranean fruit fly as a potential vector of bacterial pathogens. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005;71:4052–6.

Mastrangelo T, Parker AG, Jessup A, Pereira R, Orozco-Davila D, Islam A, Dammalage T, Walder JMM. A new generation of X ray irradiators for insect sterilization. J Econ Entomol. 2010;103:85–94.

Lauzon CR, Potter SE. Description of the irradiated and nonirradiated midgut of Ceratitis capitata Wiedemann (Diptera: Tephritidae) and Anastrepha ludens Loew (Diptera: Tephritidae) used for sterile insect technique. J Pest Sci. 2012;85:217–26.

Broderick NA. Friend, foe or food? Recognition and the role of antimicrobial peptides in gut immunity and Drosophila-microbe interactions. Philos Trans R Soc B. 2016;371:20150295. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2015.0295.

Keeney KM, Finlay BB. Enteric pathogen exploitation of the microbiota-generated nutrient environment of the gut. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2011;14:92–8.

Ashida H, Ogawa M, Kim M, Mimuro H, Sasakawa C. Bacteria and host interactions in the gut epithelial barrier. Nat Chem Biol. 2012;8:36–45.

Sanders ME. Probiotics: definition, sources, selection, and uses. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:S58–61.

Drew RAI, Courtice AC, Teakle DS. Bacteria as a natural source of food for adult fruit flies (Diptera: Tephritidae). Oecologia. 1983;60:279–84.

Estes AM, Segura DF, Jessup A, Wornoayporn V, Pierson EA. Effect of the symbiont Candidatus Erwinia dacicola on mating success of the olive fly Bactrocera oleae (Diptera: Tephritidae). Int J Trop Insect Sci. 2014;34(S1):S123–31.

Gavriel S, Jurkevitch E, Gazit Y, Yuval B. Bacterially enriched diet improves sexual performance of sterile male Mediterranean fruit flies. J Appl Entomol. 2011;135:564–73.

Meats A, Streamer K, Gilchrist AS. Bacteria as food had no effect on fecundity during domestication of the fruit fly, Bactrocera tryoni. J Appl Entomol. 2009;133:633–9.

Niyazi N, Lauzon CR, Shelly TE. Effect of probiotic adult diets on fitness components of sterile male Mediterranean fruit flies (Diptera : Tephritidae) under laboratory and field cage conditions. J Econ Entomol. 2004;97:1570–80.

Murphy KM, Macrae IC, Teakle DS. Nitrogenase activity in the Queensland fruit fly, Dacus tryoni. Aust J Biol Sci. 1988;41:447–51.

Yao M, Zhang H, Cai P, Gu X, Wang D, Ji Q. Enhanced fitness of a Bactrocera cucurbitae genetic sexing strain based on the addition of gut-isolated probiotics (Enterobacter spec.) to the larval diet. Entomol Exp Appl. 2017;162:197–203.

Hely PC, Pasfield G, Gellatley JG. Insect pests of fruit and vegetables in NSW. Clayton: Incata Press; 1982.

Queensland Fruit Fly, Bactrocera tryoni http://www.ces.csiro.au/aicn/name_c/a_3371.htm. Acessed: 29 Mar 2017.

Sacchetti P, Ghiardi B, Granchietti A, Stefanini FM, Belcari A. Development of probiotic diets for the olive fly: evaluation of their effects on fly longevity and fecundity. Ann Appl Biol. 2014;164:138–50.

Deutscher AT, Reynolds OL, Chapman TA. Yeast: an overlooked component of Bactrocera tryoni (Diptera: Tephritidae) larval gut microbiota. J Econ Entomol. 2017;110:298–300.

Shin SC, Kim SH, You H, Kim B, Kim AC, Lee KA, Yoon JH, Ryu JH, Lee WJ. Drosophila microbiome modulates host developmental and metabolic homeostasis via insulin signaling. Science. 2011;334:670–4.

Hatoum R, Labrie S, Fliss I. Antimicrobial and probiotic properties of yeasts: from fundamental to novel applications. Front Microbial. 2012;3:421. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2012.00421.

Rosa CA, Morais PB, Lachance M, Pimenta RS, Santos RO, Trindade RC, Figueroa DL, Resende MA, Bragança MAL. Candida azymoides sp. n. (Ascomycota: Saccharomycetes) a yeast species from tropical fruits and larvae of Anastrepha mucronota (Diptera: tephritidae). Lundiana. 2006;7:83–6.

Rosa CA, Morais PB, Lachance MA, Santos RO, Melo WGP, Viana RHO, Braganca MAL, Pimenta RS. Wickerhamomyces queroliae sp. nov. and Candida jalapaonensis sp. nov., two yeast species isolated from Cerrado ecosystem in North Brazil. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2009;59:1232–6.

Piper AM, Farnier K, Linder T, Speight R, Cunningham JP. Two gut-associated yeasts in a tephritid fruit fly have contrasting effects on adult attraction and larval survival. J Chem Ecol. 2017;43:891–901.

Ballard JWO, Melvin RG. Tetracycline treatment influences mitochondrial metabolism and mtDNA density two generations after treatment in Drosophila. Insect Mol Biol. 2007;16:799–802.

Woruba D, Morrow J, Reynolds O, Chapman T, Collins D, Riegler M. Diet and irradiation effects on the bacterial community composition and structure in the gut of domesticated teneral and mature Queensland fruit fly, Bactrocera tryoni (Diptera: Tephritidae). BMC Microbiol. 2019; accepted.

Deutscher A, Burke C, Darling A, Riegler M, Reynolds O, Chapman T. Near full-length 16S rRNA gene next-generation sequencing revealed Asaia as a common midgut bacterium of wild and domesticated Queensland fruit fly larvae. Microbiome. 2018;6:85.

Acknowledgements

We thank Cheryl Jenkins for comments on an earlier version of the manuscript. We thank Anne Johnson for formatting sections of this work.

About this supplement

This article has been published as part of BMC Microbiology Volume 19 Supplement 1, 2019: Proceedings of an FAO/IAEA Coordinated Research Project on Use of Symbiotic Bacteria to Reduce Mass-rearing Costs and Increase Mating Success in Selected Fruit Pests in Support of SIT Application: microbiology. The full contents of the supplement are available online at https://bmcmicrobiol.biomedcentral.com/articles/supplements/volume-19-supplement-1.

Funding

This project has been funded by Hort Innovation using the summer fruit industry levy with co-investment from NSW Department of Primary Industries and funds from the Australian Government as part of the SITplus initiative. Hort Innovation is the grower owned, not-for-profit research and development corporation for Australian horticulture.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AD drafted and wrote the manuscript with input from OR, MR, & TC. LS developed Fig. 1 with input from all authors. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution IGO License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/igo/) which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source is given.

About this article

Cite this article

Deutscher, A.T., Chapman, T.A., Shuttleworth, L.A. et al. Tephritid-microbial interactions to enhance fruit fly performance in sterile insect technique programs. BMC Microbiol 19 (Suppl 1), 287 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12866-019-1650-0

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12866-019-1650-0