Abstract

Background

Shigella spp., facultative anaerobic bacilli of the family Enterobacteriaceae, are one of the most common causes of diarrheal diseases in human worldwide which have become a significant public health burden. So, we aimed to analyze the antimicrobial phenotypes and to elucidate the molecular mechanisms underlying resistance to cephalosporins and fluoroquinolones in Shigella isolates from patients with diarrhea in Shanxi Province.

Results

During 2006–2016, we isolated a total of 474 Shigella strains (including 337 S. flexneri and 137 S. sonnei). The isolates showed high rates of resistance to traditional antimicrobials, and 26, 18.1 and 3.0% of them exhibited resistance to cephalosporins, fluoroquinolones and co-resistance to cephalosporins and fluoroquinolones, respectively. Notably, 91.1% of these isolates, including 22 isolates that showed an ACTSuT profile, exhibited multidrug resistance (MDR). The resistance rates to cephalosporins in S. sonnei isolates were higher than those in S. flexneri. Conversely, the resistance rates to fluoroquinolones were considerably higher in S. flexneri isolates. Among the 123 cephalosporins-resistant isolates, the most common extended-spectrum beta-lactamase gene was blaTEM-1, followed by blaCTX-M, blaOXA-1, and blaSHV-12. Six subtypes of blaCTX-M were identified, blaCTX-M-14 (n = 36) and blaCTX-M-55 (n = 26) were found to be dominant. Of all the 86 isolates with resistance to fluoroquinolones and having at least one mutation (Ser83Leu, His211Tyr, or Asp87Gly) in the the quinolone resistance-determining regions of gyrA, 79 also had mutation of parC (Ser80Ile), whereas 7 contained plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance genes including qnrA, qnrB, qnrS, and aac(60)-Ib-cr. Furthermore, pulsed-field gel electrophoresis analysis (PFGE) showed a considerable genetic diversity in S. flexneri isolates. However, the S. sonnei isolates had a high genetic similarity.

Conclusions

Coexistence of diverse resistance genes causing the emergence and transmission of MDR might render the treatment of shigellosis difficult. Therefore, continuous surveillance might be needed to understand the actual disease burden and provide guidance for shigellosis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Shigella spp., facultative anaerobic bacilli of the family Enterobacteriaceae, are one of the most common causes of diarrheal diseases in human worldwide and have become a significant public health burden [1]. Globally, nearly 167 million Shigella episodes per year are estimated, of which 99% are reported in developing countries. It is reported that almost 61% of all deaths attributed to shigellosis are in children under 5 years old [2]. In China, nearly half a million shigellosis cases are reported every year, which is situated at the top four notifiable infectious disease [2].

Researchers have classified the genus Shigella into 4 serogroups: S. dysenteriae, S. flexneri, S. boydii, and S. sonnei based on biochemical and serological properties. The S. flexneri is the predominant species in developing countries [1], where is in poor sanitation, such as in mainland China. Otherwise, the S. sonnei is mainly found in industrialized countries [2, 3], and has been implicated in source outbreaks [4]. However, in some Asian countries and some developed regions of China, S. sonnei is gradually overtaking S. flexneri as the main pathogenic bacteria that cause shigellosis [5,6,7,8].

Based on the national surveillance data from 2009, the annual shigellosis-related morbidity rate was 20.3 cases per 100,000 people in China, and the two major causative species were S. flexneri and S. sonnei [9]. To date, at least 20 S. flexneri serotypes have been recognized and reported, such as 1a, 1b, 1c (or 7a), 1d, 2a, 2b, 2v, 3a, 3b, 4a, 4av, 4b, 5a, 5b, X, Xv, Y, Yv, 6, and 7b [10, 11]. Some new serotypes such 4 s and 2 variants have been found and disseminated in China, likely leading to a serious threat to public health security [11, 12]. In some developing countries, S. flexneri 1b is the most commonly encountered serotypes, followed by S. flexneri 2a [1].

Infants, the elderly, and immunocompromised individuals with Shigella infection require antimicrobial treatment to shorten the clinical symptom duration and carriage and reduce the spread of infection [13]. The World Health Organization recommends fluoroquinolones and cephalosporins as the preferred drugs for the treatment of Shigella infections. With the extensive use of these antimicrobials, antimicrobial resistance is increasing remarkably in Shigella isolates. Since the first report of norfloxacin-resistant Shigella in 1949 in Japan [14], increasing number of Shigella isolates with multiple drug resistance (MDR, defined as resistance to three or more classes of antimicrobials) has been discovered in the world. It was reported that some factors could influence the antimicrobial susceptibility patterns of Shigella isolates, such as the geographic location, year, antimicrobial use, and antimicrobial agents [15]. However, few studies have investigated the antimicrobial resistance of Shigella in different cities of China, such as Shanghai and Beijing [5, 6].

Selection of the most effective antimicrobial agents for shigellosis treatment requires the understanding of the antimicrobial susceptibility profiles of prevalent strains [16]. This study aimed to analyze the antimicrobial resistance profiles of Shigella isolates from Shanxi Province during 2006 to 2016, and to elucidate the molecular mechanisms underlying the emergence of MDR in these isolates.

Results

Bacterial isolates, serotyping, and biochemical characterization

During our 11-year routine surveillance (from 2006 and 2016) of shigellosis, a total of 474 Shigella isolates, including 337 S. flexneri (71.1%) strains and 137 S. sonnei (28.9%) isolates, but no S. dysenteriae and S. boydii were identified from patients with diarrhea in Shanxi Province. The age of the patients ranged from 2 months to 87 years (Fig. 1). The patients aged 15–59 years accounted for the highest proportion of 36.5% of all age groups (n = 173), whereas patients over 60 years old were the least susceptible, with a proportion of 6.3% (n = 30). Among all age groups, the proportion of males was higher than that of females (Fig. 1b). The male to female ratio for the patients was 1.42:1. Among the Shigella isolates, the constituent ratio of S. flexneri was higher than that of S. sonnei isolates every year, except in 2011 and 2016 (Fig. 2). Several S. flexneri serotypes were found in the 337 S. flexneri isolates, including serotypes 1a, 1b, 2a, 2b, 4c, and 5b. Notably, serotypes 4c and 1a were the main serotypes, accounting for 43 and 30%, respectively (Fig. 3). These results suggested that S. sonnei and S. flexneri are the prevalent species in Shanxi Province of China, especially the S. flexneri serotypes 4c and 1a.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing

Among the 474 isolates, only 2 (0.4%) were susceptible to all 21 antimicrobials. Resistance to ampicillin was the most common (97.7%), followed by that to ticarcillin (94.9%), trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (88.4%), tetracycline (78.3%), chloramphenicol (57.4%), gentamicin (40.5%), cefazolin (26.2%), ceftriaxone (26.0%), norfloxacin (18.1%), cefoperazone (17.9%), piperacillin (16.0%), tobramycin (8.9%), aztreonam (5.7%), levofloxacin (2.3%), ticarcillin/clavulanic acid (1.7%), imipenem (0.8%), ceftazidime (0.6%), cefoxitin and amikacin (0.2%). None of the isolates was resistant to cefepime and nitrofurantoin (Table 1). The antibiotic resistance rates differed between S. sonnei and S. flexneri. The resistance rates of S. flexneri isolates to the top three antibiotics ampicillin, ticarcillin, and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole were 98.5, 95.0, and 85.2%, respectively. However, the resistance rate to trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole (96.4%) was the highest in S. sonnei, which was considerably higher than that of S. flexneri, followed by that to ampicillin (95.6%) and ticarcillin (94.9%). Further, the resistance rates for tetracycline, gentamicin, and piperacillin were considerably higher in S. sonnei isolates, especially to cephalosporins, such as cefazolin, ceftriaxone, cefoperazone, and ceftazidime (P < 0.05). However, the resistance rates for chloramphenicol, norfloxacin, and levofloxacin in S. flexneri were considerably higher than those in S. sonnei isolates (P < 0.05). (Table 1). None of the S. sonnei isolates was resistance to cefoxitin and amikacin; the S. flexneri isolates also showed a low resistance rate (0.3%) to both the antibiotics. More importantly, 14 (3.0%) isolates showed co-resistance to third-generation cephalosporins and fluoroquinolones.

Moreover, notable differences were noted in antibiotic resistance profiles especially those changed significantly during 2006–2011 and 2012–2016. Of all the Shigella strains, the resistance rate to cefazolin, ceftriaxone, norfloxacin, and aztreonam was 23.8, 24.2, 15.5, and 1.8%, respectively, during 2006–2011, and increased to 29.4, 28.4, 26.9, and 11.2% during 2012–2016. Conversely, the resistance rate to piperacillin, tobramycin, Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, tetracycline, and chloramphenicol was 18.8, 12.3, 90.3, 85.6, and 64.6%, respectively, during 2006–2011 and decreased to 12.2%. 4.1, 85.8, 68.0, and 47.2% during 2012–2016 (Table 2).

Further, MDR was observed in 91.1% (n = 432) of the isolates, of which 91.1, 70.7, and 24.9% were resistant to ≥3, ≥ 4, and ≥ 5 CLSI classes of antimicrobials were found in, respectively (Table 3). Among the MDR isolates, 412 (86.5%), 242 (50.1%), and 22 (4.6%) isolates showed an AT/S (defined as resistance to ampicillin and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole), ACT/S (defined as resistance to ampicillin, chloramphenicol, and trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole) and ACTSuT resistance pattern (defined as resistance to ampicillin, chloramphenicol, tobramycin, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole and tetracycline), respectively.

Molecular analysis of antibiotic-resistant determinants and integrons

A total of 195 Shigella isolates (including 109 cephalosporin-resistant isolates, 72 quinolone-resistant isolates, and 14 co-resistance isolates) were tested for the presence of antimicrobial resistance determinants and integrons. PCR results showed that all 195 tested isolates were negative for blaVIM and blaNDM, but positive for blaSHV, blaTEM, blaOXA, blaCTX-M, intI1 and intI2 gene regions (Table 4). Further, 90 (73.2%, n = 123) isolates harbored blaTEM, and sequencing results of blaTEM showed 100% identity with blaTEM-1. Moreover, 71 isolates were positive for blaCTX-M, of which 36 isolates harbored blaCTX-M-14, 4 harbored blaCTX-M-15, 26 (21.1%, n = 123) harbored blaCTX-M-55, 2 isolates harbored blaCTX-M-28 and blaCTX-M-64 each, and only one isolate simultaneously harbored both blaCTX-M-3 and blaCTX-M-14 (Fig. 4). Forty-nine isolates harbored blaOXA-1, with a positive rate of 39.8%. Eighteen strains were positive for blaSHV. Among the tested isolates, 139 and 167 isolates contained class 1 and class 2 integrons, respectively. Class 1 integrons positive isolates includ 16 S. sonnei isolates and 123 S. flexneri isolates, therefore class 2 positive isolates include 47 S. sonnei strains and 120 S. flexneri strains. All class 1 integrons harbored blaOXA-1, which is present on the Tn2603 transposons [17] and aadA1 gene cassettes, whereas class 2 integrons are included in dfrA1, sat1, and aadA1 gene cassettes.

Among the 86 quinolone-resistant isolates, no point mutations were noted in the QRDRs of gyrB and parE, but point mutations were noted in gyrA and parC in the most resistant isolates. All the 86 quinolone-resistant isolates had the gyrA mutation of Ser83Leu and His211Tyr; 7 isolates had the gyrA mutation of Asp87Gly; and 79 had the parC mutation of Ser80Ile. Seven isolates were positive for qnrA, qnrB and acc(6′)-Ib-cr. Forty-five (52.3%) isolates were positive for qnrS.

Notably, among the 14 isolates that concurrently exhibited reduced susceptibility to cephalosporins and quinolone, 13 contained ESBL and PMQR genes. Six isolates contained four types of antimicrobial-resistant genes: blaCTX-M-55/blaOXA/blaTEM/qnrS (n = 2) and blaCTX-M-55/blaOXA/blaTEM/ qnrB (n = 1), blaOXA/blaTEM/blaCMY/qnrS (n = 1), blaCTX-M-14/blaOXA/blaTEM/qnrS (n = 1), and blaCTX-M-14/blaTEM/qnrS/acc (6′)-Ib-cr (n = 1). Five isolates contained three types of genes: blaCTX-M-3/qnrS/ acc (6′)-Ib-cr, blaOXA/blaTEM/qnrS, blaCTX-M-15/blaOXA/blaSHV, blaCTX-M-14/blaTEM/qnrS, and blaCTX-M-55/blaTEM/qnrS (all n = 1). Two isolates had two types of genes: blaCTX-M-14/blaTEM and blaTEM/qnrS (n = 1 each). Only one isolate did not have any resistance genes (Table 5).

PFGE analysis

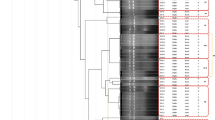

PFGE was performed to determine the genetic relatedness among the 75 randomly selected Shigella isolates from different years and regions in Shanxi Province. The results of PFGE suggested that the 38 S. flexneri isolates generated 36 PFGE patterns (Fig. 5 a). All isolates could be categorized into four distinct groups (A-D) with a similarity of approximately 82%, including F1a, F2a, F2b, F4c, and F5b serotypes. This suggests considerable genetic diversity among the 38 S. flexneri isolates between different regions and years in Shanxi Province. Notably, group B was the major PFGE type of S. flexneri in Shanxi. Conversely, the 37 S. sonnei strains generated 25 PFGE patterns (Fig. 5 b), but formed a single cluster except one isolate (LJ-11-005) with a similarity of 82%. This result suggested that the S. sonnei strains had high genetically similarity in Shanxi Province.

Discussion

The emergence of novel and atypical bacterial serotypes in nature is attributed to serotype conversion, which often occurs in response to the protective host immune response [18]. Since the 1990s, several new S. flexneri serotypes (e.g., 1c and SFxv) have emerged and become the most prevalent ones in some countries [19]. SFxv, first appeared in Henan Province, China, in 2001 and was considered one of the predominant serotypes in Shanxi, Gansu, and Anhui Provinces from 2002 to 2006 [19, 20]. The prevalence and characterization of human Shigella infections in Henan Province, China were determined in 2006 [20]. Data on the prevalence of S. flexneri serotypes causing shigellosis in mainland China from 2001 to 2010 suggest that SFxv is the second most predominant serotype after 2a [21]. However, our results showed that the top three common Shigella serotypes in Shanxi Province were S. sonnei, S. flexneri serotypes 4c and 1a, which differed from those reported previously [18,19,20,21]. Interestingly, our data indicated that S. sonnei has replaced S. flexneri as the predominant species causing shigellosis in Shanxi Province, which was consistent with the findings of previous studies [5, 6]. The increasing of proportion of S. sonnei is related to regional economic development and sanitary conditions. Shanxi is a developing and mountainous province with poor sanitary, which could promote the increasing of S. sonnei strains. Furthermore, it could also be conducive to the prevalence and dissemination of S. sonnei strains with MDR.

In our study, S. flexneri tended to gradually increase and reach a peak in 2011, and then slowly decline again, whereas S. sonnei showed an opposite tendency. These trends and patterns were similar with those noted in developed countries [22]. The increasing antimicrobial resistance of Shigella species is a major problem in the treatment of Shigella gastroenteritis, especially of the MDR Shigella strains. Approximately 91.1% of the strains in our study showed MDR profiles, which is significantly higher than the rate of 41.6% (1762/4234) from the NARMS report (2005~2014) [23]. All the MDR strains were highly resistant to the traditional antimicrobials such as ampicillin, ticarcillin, trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, and tetracycline. One of the reasons for the rapid accumulation of resistance has been reported to be the excessive or inappropriate use of antibiotics in outpatients in China [24, 25].

Fluoroquinolones and third-generation cephalosporins are the recommended first-line and alternatives drugs by the World Health Organization for empiric shigellosis treatment [26]. Our study further indicated that the current resistance patterns have changed, and empirical therapy should be modified in accordance with these changes. Thus, the treatment should be based on the susceptibility patterns and antimicrobials with current resistance might become effective in the future.

Moreover, in our study, 26.2% of cephalosporins-resistant Shigella isolates were found, which was considerably higher than the rate indicated in the NARMS report (lower than 1% from 2005 to 2014). The S. sonnei isolates showed higher resistance rates to cephalosporins, whereas the S. flexneri isolates had higher level resistance to fluoroquinolones. More importantly, we found 14 MDR isolates with co-resistance to fluoroquinolones and cephalosporins. If these MDR strains are prevalent worldwide, it might become a remarkable global public health concern. Our findings indicated that continuing monitor the antimicrobial resistance of Shigella isolates is necessary to help determine the appropriate antimicrobial therapy for patients with Shigella infection. More importantly, determining the mechanisms of antimicrobial resistance is necessary to assist in developing measures to prevent antibiotic resistance.

The increasing antibiotic resistance and rate led us to investigate the genetics and mechanisms of antibiotic resistance. Under the influence of various antibiotics, bacteria have a strong ability to obtain resistance genes for survival. Class 1 and class 2 integrons, which contain resistance genes and can be coordinately excised or integrated [2], might account for the horizontal transfer of resistance genes. In our study, 71.3% (n = 139) and 85.6% (n = 167) of isolates harbored class 1 and class 2 integrons, followed by the blaOXA-1 + aadA1 and dfrA1 + sat1 + aadA1 gene cassettes, conferring resistance to trimethoprim and streptomycin [27].

In addition, of the 123 cephalosporin-resistant isolates, 73.2% harbored the blaTEM-1 resistance gene, 57.7% harbored blaCTX-M, most of which were blaCTX-M-14, followed by blaCTX-M-55, blaCTX-M-15, blaCTX-M-28, and blaCTX-M-64. Further, 39.8% harbored blaOXA, and 14.6% harbored blaSHV. The blaTEM-1 gene exists at high frequencies in antibiotic-resistance bacteria and often confers resistance to penicillin and other β-lactamic antibiotics [28]. whereas the OXA-type β-lactamic, with high hydrolytic activity against oxacillin and cloxacillin often confer resistance to ampicillin and cephalothin [29]. Sequencing analysis showed that all the blaOXA genes were blaOXA-1, which is consistent with the findings of a previous study on Shigella strains [30]. Plasmid-mediated transfer of different blaCTX-M genes was thought to be the reason for introduction of these genes into the isolates at different times [25], indicating that blaCTX-M-14 and blaCTX-M-55 genes might have long been circulating among Shigella isolates in Shanxi Province.

PMQR was initially identified in Klebsiella pneumoniae in 1998 [31]; since then, various types of PMQR genes have been detected worldwide. Quinolone levels and/or fluoroquinolone resistance have been mostly attributed to mutations in the target enzymes gyrase (gyrA and gyrB) and topoisomerase IV (parC and parE), and the presence of plasmid-borne mechanisms owing to the proteins encoded by qnrA, qnrB, qnrS and aac(6′)-Ib-cr [32, 33]. The mutations of gyrA and parC at positions 67–106 are known to be the predominant mutations that can lead to fluoroquinolone resistance [34]. The gyrA Ser83Leu is the most frequently observed in Shigella species, and usually results in high-level resistance to the first-generation quinolone nalidixic acid [35]. The presence of additional mutations of gyrA (Asp87Gly/Asn and His211Tyr) and parC (Ser80Ile) results in resistance to fluoroquinolones [36]. Moreover, the mutation of His211Tyr in gyrA is very common in fluoroquinolone-resistant Shigella [30]. In our study, 100% of the quinolone-resistant Shigella isolates had point mutations in gyrA (Ser83Leu, Asp87Gly/Asn, and His211Tyr) and parC (Ser80Ile). S. flexneri serotypes (such as 1a, 2a, 2b, and 4c) carrying the qnrS gene have been globally reported with low incidence [37, 38]. In our study, 45 (52.3%) of the strains contained qnrS, of which 11 showed high resistance to levofloxacin and norfloxacin. The aac(6′)-Ib-cr is reported to be responsible for low-level resistance to fluoroquinolones [39] and was first isolated from Shigella strains in 1998 [38]. Moreover, seven of the quinolone-resistant isolates were aac(6′)-Ib-cr–positive, suggesting that the qnrS and aac(6′)-Ib-cr genes had long been present in Shanxi Province. The qnrA and qnrB were reported to be located on plasmids carrying bla genes (such as blaSHV and blaCTX) [40]. In this study, seven strains also contained qnrA and qnrB each, and the qnrB-positive isolate coharbored blaCTX-M-55, blaOXA, and blaTEM. Our results are consistent with those of previous studies and the theory suggesting quinolone resistance determinants alone might have a weak effect on resistance levels; however, when combined with other determinants, resistance can be obtained [41]. The various resistance genes facilitate the dissemination of resistance determinants and the survival of bacteria under the selective pressure of various antibiotics.

Besides, in our study, the PFGE dendrogram showed that the S. sonnei isolates are closely related (82% similarity), indicating that they are possibly derived from a common parental strain. In contrast, the S. flexneri isolates (including F1a, F2a, F2b, F4c, and F5b serotypes) showed lower degrees of similarity, suggesting that they are likely derived from diverse sources, such as from different years, sources or origins. And the group B PFGE pattern was the major PFGE type of S. flexneri in Shanxi Province. Although PFGE has high concordance with epidemiological and genetical relatedness, and is considered as the “gold standard” fingerprinting method used for the discrimination and identification within PulseNet, it might not be effective in some Shigella or Salmonella species, which warrants further investigation with complementary molecular tools as multilocus sequence typing (MLST) [42].

Conclusions

In summary, we reported the distribution of Shigella serotypes and analyzed the common occurrence of MDR and resistance mechanisms in Shigella isolates in Shanxi Province during 2006 and 2016, China. The diverse antimicrobial resistance patterns and multi-types resistance genes were observed. Future studies should be focused on identifying ways to prevent the dissemination of these antimicrobial-resistance genes. Our data might provide a strategy for the treatment of infections caused by Shigella strains in Shanxi Province, China. Therefore, continuous surveillance might be imperative to determine the distribution and resistance development of Shigella, and to understand the actual disease burden and provide guidance for the clinical treatment of shigellosis. Furthermore, without treatment of shigellosis, especially caused the MDR Shigella, it might become a dominant strain and be prevalent in Shanxi Province, and spread worldwide, leading to the outbreaks of Shigella and causing significant public health and disease burden.

Materials

Bacterial isolates, serotyping, and biochemical characterization

All the Shigella strains were isolated from fresh fecal samples, which were collected from outpatients with diarrhea or dysentery in four sentinel hospitals and two regional Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (one in Taiyuan City and the other in Yicheng County) in Shanxi Province based on a provincial pathogen monitoring system. Basic epidemiological data (name, age, gender, date, and region of isolation of patients) were recorded for each isolate. We screened for Shigella species by using the methods as reported previously [12, 30]. Resultant colonies on the Salmonella-Shigella (SS) agar were transferred to our Microbiology Laboratory of Shanxi CDC for further confirmation. API 20E test strips (bioMerieux Vitek; Marcy-1′Etoile, France) and two specific serotyping kits were used to identify all the types and groups of S. flexneri. The slide agglutination test was used for serological reactions as reported previously [43].

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing

The antimicrobial susceptibility of all the Shigella isolates (474 Shigella strains, including 137 S. sonnei and 337 S. flexneri) was determined by analyzing the minimum inhibitory concentrations (MICs) of 21 antimicrobial agents, which were tested using the Sensititre semi-automated antimicrobial susceptibility system (TREK Diagnostics, Inc., Westlake, OH, USA) and the Sensititre 96-well plate PRCM2F (Thermo Fisher Scientific Ine, West Sussex, UK) according to the recommendations of the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI, 2019) [44], as described previously [12, 30]. The 21 antimicrobial agents included CAZ, CRO, FEP, CFP, CFZ, FOX, IPM, NIT, PIP, AMP, TIC, TE, TO, GEN, AK, ATM, C, TIM, LEV, NOR, and SXT. The Escherichia coli ATCC 25922 was used as quality control.

Tests for antibiotic-resistance genes and integrons

The genomic DNA of each isolate was extracted and purified using a commercial Bacteria DNA Kit (TIANGEN Biotech, China). Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) assays were performed as reported previously to screen for resistance genes and intergrons, such as β-lactamase [27, 38, 45,46,47], quinolone resistance-determining region (QRDR) [48], plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance (PMQR) [38, 45, 49], and variable regions of classes 1 and 2 integrons [30] (See Additional file 1). The resultant PCR products were sequenced, assembled and edited using the software Seqman (DNAstar Inc., Madison, WI, USA). We assessed the nucleotide sequence similarity by using the BLST from the NCBI GenBank database (http://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi).

Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE)

The genetic relationship among the Shigella species isolated from Shanxi Province was determined by analyzing 37 S. sonnei strains and 38 S. flexneri strains by using pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) according to the standard protocol for Shigella outlined by PulseNet [50]. Macrorestriction patterns and dendrograms were analyzed and constructed using the methods as described previously [12, 30], but with a different position tolerance of 1.5%.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Chi-square test by using SPSS statistical package v.19.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). We compared the antibiotic resistance rates between the ages, gender, serotypes, and locations of the patients. A P value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and analyzed during the current study are available from corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- AK:

-

Amikacin

- AMP:

-

Ampicillin

- ATM:

-

Aztreonam

- C:

-

Chloramphenicol

- CAZ:

-

Ceftazidime

- CFP:

-

Cefoperazone

- CFZ:

-

Cefazolin

- CLSI:

-

Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute

- CRO:

-

Ceftriaxone

- FEP:

-

Cefepime

- FOX:

-

Cefoxitin

- GN:

-

Gentamicin

- IMP:

-

Imipenem

- LEV:

-

Levofloxacin

- MDR:

-

Multidrug resistance

- MIC:

-

Minimum inhibitory concentration

- NARMS:

-

National antimicrobial resistance monitoring system

- NIT:

-

Nitrofurantoin

- NOR:

-

Norfloxacin

- PCR:

-

Polymerase chain reaction

- PFGE:

-

Pulsed-field gel electrophoresis

- PIP:

-

Piperacillin

- PMQR:

-

Plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance

- QRDR:

-

Quinolone resistance-determining region

- SXT:

-

Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole

- TE:

-

Tetracycline

- TIC:

-

Ticarcillin

- TIM:

-

Ticarcillin/clavulanic acid

- TO:

-

Tobramycin

References

Kotloff KL, Winickoff JP, Ivanoff B, Clemens JD, Swerdlow DL, Sansonetti PJ, et al. Global burden of Shigella infections: implications for vaccine development and implementation of control strategies. Bull World Health Organ. 1999;77(8):651–66.

Ke X, Gu B, Pan S, Tong M. Epidemiology and molecular mechanism of integron-mediated antibiotic resistance in Shigella. Arch Microbiol. 2011;193(11):767–74.

Gupta A, Polyak CS, Bishop RD, Sobel J, Mintz ED. Laboratory-confirmed shigellosis in the United States, 1989-2002: epidemiologic trends and patterns. Clinical infectious diseases : an official publication of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. 2004;38(10):1372–7.

Ma Q, Xu X, Luo M, Wang J, Yang C, Hu X, et al. A waterborne outbreak of Shigella sonnei with resistance to azithromycin and third-generation Cephalosporins in China in 2015. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2017;61(6):e00308–17.

Qu F, Bao C, Chen S, Cui E, Guo T, Wang H, et al. Genotypes and antimicrobial profiles of Shigella sonnei isolates from diarrheal patients circulating in Beijing between 2002 and 2007. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2012;74(2):166–70.

Zhang J, Jin H, Hu J, Yuan Z, Shi W, Yang X, et al. Antimicrobial resistance of Shigella spp. from humans in Shanghai, China, 2004-2011. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2014;78(3):282–6.

Banga Singh KK, Ojha SC, Deris ZZ, Rahman RA. A 9-year study of shigellosis in Northeast Malaysia: antimicrobial susceptibility and shifting species dominance. Zeitschrift fur Gesundheitswissenschaften Journal of public health. 2011;19(3):231–6.

Seol SY, Kim YT, Jeong YS, Oh JY, Kang HY, Moon DC, et al. Molecular characterization of antimicrobial resistance in Shigella sonnei isolates in Korea. J Med Microbiol. 2006;55(Pt 7:871–7.

SUI Jilin ZJ, Junling SUN, Zhaorui CHANG, Weidong ZHANG, Zijun WANG. Surveillance of bacillary dysentery in China, 2009. Disease Surveillance, vol. 12; 2010. p. 4.

Sun Q, Lan R, Wang J, Xia S, Wang Y, Wang Y, et al. Identification and characterization of a novel Shigella flexneri serotype Yv in China. PLoS One. 2013;8(7):e70238.

Qiu S, Wang Y, Xu X, Li P, Hao R, Yang C, et al. Multidrug-resistant atypical variants of Shigella flexneri in China. Emerg Infect Dis. 2013;19(7):1147–50.

Yang C, Li P, Zhang X, Ma Q, Cui X, Li H, et al. Molecular characterization and analysis of high-level multidrug-resistance of Shigella flexneri serotype 4s strains from China. Sci Rep. 2016;6:29124.

Salam MA, Bennish ML. Antimicrobial therapy for shigellosis. Rev Infect Dis. 1991;13(Suppl 4):S332–41.

Watanabe T. Infective heredity of multiple drug resistance in bacteria. Bacteriol Rev. 1963;27:87–115.

Pickering LK. Antimicrobial resistance among enteric pathogens. Semin Pediatr Infect Dis. 2004;15(2):71–7.

Hoffman RE, Shillam PJ. The use of hygiene, cohorting, and antimicrobial therapy to control an outbreak of shigellosis. American journal of diseases of children (1960). 1990;144(2):219–21.

Siu LK, Lo JY, Yuen KY, Chau PY, Ng MH, Ho PL. beta-lactamases in Shigella flexneri isolates from Hong Kong and Shanghai and a novel OXA-1-like beta-lactamase, OXA-30. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44(8):2034–8.

Allison GE, Verma NK. Serotype-converting bacteriophages and O-antigen modification in Shigella flexneri. Trends Microbiol. 2000;8(1):17–23.

Ye C, Lan R, Xia S, Zhang J, Sun Q, Zhang S, et al. Emergence of a new multidrug-resistant serotype X variant in an epidemic clone of Shigella flexneri. J Clin Microbiol. 2010;48(2):419–26.

Xia S, Xu B, Huang L, Zhao JY, Ran L, Zhang J, et al. Prevalence and characterization of human Shigella infections in Henan Province, China, in 2006. J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49(1):232–42.

Chang Z, Lu S, Chen L, Jin Q, Yang J. Causative species and serotypes of shigellosis in mainland China: systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2012;7(12):e52515.

Ekdahl K, Andersson Y. The epidemiology of travel-associated shigellosis--regional risks, seasonality and serogroups. The Journal of infection. 2005;51(3):222–9.

Prevention CfDCa. NARMS Human Isolates Surveillance Report for 2014 (Final Report). 2016, http://www.cdc.gov/narms/pdf/2014-annual-report-narms-508c.pdf.

Pickering LK. Antimicrobial resistance among enteric pathogens. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2008;609:154–63.

Zhang W, Luo Y, Li J, Lin L, Ma Y, Hu C, et al. Wide dissemination of multidrug-resistant Shigella isolates in China. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2011;66(11):2527–35.

Gendrel D, Cohen R. Bacterial diarrheas and antibiotics: European recommendations. Arch Pediatr. 2008;15 Suppl 2:S93–S96.

Pan JC, Ye R, Meng DM, Zhang W, Wang HQ, Liu KZ. Molecular characteristics of class 1 and class 2 integrons and their relationships to antibiotic resistance in clinical isolates of Shigella sonnei and Shigella flexneri. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2006;58(2):288–96.

Barlow M, Hall BG. Experimental prediction of the natural evolution of antibiotic resistance. Genetics. 2003;163(4):1237–41.

Bradford PA. Extended-spectrum beta-lactamases in the 21st century: characterization, epidemiology, and detection of this important resistance threat. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2001;14(4):933–51 table of contents.

Cui X, Yang C, Wang J, Liang B, Yi S, Li H, et al. Antimicrobial resistance of Shigella flexneri serotype 1b isolates in China. PLoS One. 2015;10(6):e0129009.

Martinez-Martinez L, Pascual A, Garcia I, Tran J, Jacoby GA. Interaction of plasmid and host quinolone resistance. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2003;51(4):1037–9.

Jacoby GA, Walsh KE, Mills DM, Walker VJ, Oh H, Robicsek A, et al. qnrB, another plasmid-mediated gene for quinolone resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2006;50(4):1178–82.

Robicsek A, Strahilevitz J, Jacoby GA, Macielag M, Abbanat D, Park CH, et al. Fluoroquinolone-modifying enzyme: a new adaptation of a common aminoglycoside acetyltransferase. Nat Med. 2006;12(1):83–8.

Alekshun MN, Levy SB. Molecular mechanisms of antibacterial multidrug resistance. Cell. 2007;128(6):1037–50.

Ding J, Ma Y, Gong Z, Chen Y. A study on the mechanism of the resistance of Shigellae to fluoroquinolones. Zhonghua nei ke za zhi. 1999;38(8):550–3.

Vila J, Ruiz J, Marco F, Barcelo A, Goni P, Giralt E, et al. Association between double mutation in gyrA gene of ciprofloxacin-resistant clinical isolates of Escherichia coli and MICs. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1994;38(10):2477–9.

Hata M, Suzuki M, Matsumoto M, Takahashi M, Sato K, Ibe S, et al. Cloning of a novel gene for quinolone resistance from a transferable plasmid in Shigella flexneri 2b. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2005;49(2):801–3.

Pu XY, Pan JC, Wang HQ, Zhang W, Huang ZC, Gu YM. Characterization of fluoroquinolone-resistant Shigella flexneri in Hangzhou area of China. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2009;63(5):917–20.

Frasson I, Cavallaro A, Bergo C, Richter SN, Palu G. Prevalence of aac(6′)-Ib-cr plasmid-mediated and chromosome-encoded fluoroquinolone resistance in Enterobacteriaceae in Italy. Gut pathogens. 2011;3(1):12.

Tamang MD, Seol SY, Oh JY, Kang HY, Lee JC, Lee YC, et al. Plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance determinants qnrA, qnrB, and qnrS among clinical isolates of Enterobacteriaceae in a Korean hospital. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2008;52(11):4159–62.

Martinez-Martinez L, Pascual A, Jacoby GA. Quinolone resistance from a transferable plasmid. Lancet (London, England). 1998;351(9105):797–9.

Woodward DL, Clark CG, Caldeira RA, Ahmed R, Soule G, Bryden L, et al. Identification and characterization of Shigella boydii 20 serovar nov., a new and emerging Shigella serotype. J Med Microbiol. 2005;54(Pt 8:741–8.

Talukder KA, Dutta DK, Safa A, Ansaruzzaman M, Hassan F, Alam K, et al. Altering trends in the dominance of Shigella flexneri serotypes and emergence of serologically atypical S. flexneri strains in Dhaka, Bangladesh. J Clin Microbiol. 2001;39(10):3757–9.

Institute CaLS. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing: 24th informational supplement M100-S24. Wayne: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2014.

Tariq A, Haque A, Ali A, Bashir S, Habeeb MA, Salman M, et al. Molecular profiling of antimicrobial resistance and integron association of multidrug-resistant clinical isolates of Shigella species from Faisalabad, Pakistan. Can J Microbiol. 2012;58(9):1047–54.

Ahmed AM, Furuta K, Shimomura K, Kasama Y, Shimamoto T. Genetic characterization of multidrug resistance in Shigella spp. from Japan. J Med Microbiol. 2006;55(Pt 12:1685–91.

Galani I, Souli M, Mitchell N, Chryssouli Z, Giamarellou H. Presence of plasmid-mediated quinolone resistance in Klebsiella pneumoniae and Escherichia coli isolates possessing bla VIM-1 in Greece. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2010;36(3):252–4.

Hu LF, Li JB, Ye Y, Li X. Mutations in the GyrA subunit of DNA gyrase and the ParC subunit of topoisomerase IV in clinical strains of fluoroquinolone-resistant Shigella in Anhui, China. J Microbiol (Seoul, Korea). 2007;45(2):168–70.

Robicsek A, Strahilevitz J, Sahm DF, Jacoby GA, Hooper DC. qnr prevalence in ceftazidime-resistant Enterobacteriaceae isolates from the United States. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2006;50(8):2872–4.

Ribot EM, Fair MA, Gautom R, Cameron DN, Hunter SB, Swaminathan B, et al. Standardization of pulsed-field gel electrophoresis protocols for the subtyping of Escherichia coli O157:H7, Salmonella, and Shigella for PulseNet. Foodborne Pathog Dis. 2006;3(1):59–67.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all the patients for agreeing to be included in this study.

Funding

This research was funded in part by the Key projects of the National Key R@D Program of China (2017YFC1600101 and 2017YFC1600104). The funding bodies had no influence in the design of this study or the collection, analysis, or interpretation of data as well as in writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

HY designed the study, XX participated in the collection of the samples. QZ, SY, JH, and BR completed identification and preservation of samples, YW was responsible for the experiments. YW and QM analyzed the data. QM wrote the manuscript, and SQ provided the lab and academic revision for the manuscript. We seriously declare that all authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Our study was approved by the Ethics Review Committee of Shanxi Province Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Informed oral and written consent was obtained from all patients included in this study.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional file

Additional file 1:

Table S1. Primers for the PCR detection of antimicrobial-resistance determinants used in this study. (PDF 165 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, Y., Ma, Q., Hao, R. et al. Antimicrobial resistance and genetic characterization of Shigella spp. in Shanxi Province, China, during 2006–2016. BMC Microbiol 19, 116 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12866-019-1495-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12866-019-1495-6