Abstract

Background

Poultry farming and consumption of poultry (Gallus gallus domesticus) meat and eggs are common gastronomical practices worldwide. Till now, a detailed understanding about the gut colonisation of Gallus gallus domesticus by yeasts and their virulence properties and drug resistance patterns in available literature remain sparse. This study was undertaken to explore this prevalent issue.

Results

A total of 103 specimens of fresh droppings of broiler chickens (commercial G domesticus) and domesticated chickens (domesticated G domesticus) were collected from the breeding sites. The isolates comprised of 29 (33%) Debaryozyma hansenii (Candida famata), 12 (13.6%) Sporothrix catenata (C. ciferrii), 10 (11.4%) C. albicans, 8 (9.1%) Diutnia catenulata (C. catenulate), 6 (6.8%) C. tropicalis, 3 (3.4%) Candida acidothermophilum (C. krusei), 2 (2.3%) C. pintolopesii, 1 (1.1%) C. parapsilosis, 9 (10.2%) Trichosporon spp. (T. moniliiforme, T. asahii), 4 (4.5%) Geotrichum candidum, 3 (3.4%) Cryptococcus macerans and 1 (1%) Cystobasidium minuta (Rhodotorula minuta). Virulence factors, measured among different yeast species, showed wide variability. Biofilm cells exhibited higher Minimum Inhibitory Concentration (MIC) values (μg/ml) than planktonic cells against all antifungal compounds tested: (fluconazole, 8–512 vs 0.031–16; amphotericin B, 0.5–64 vs 0.031–16; voriconazole 0.062–16 vs 0.062–8; caspofungin, 0.062–4 vs 0.031–1).

Conclusions

The present work extends the current understanding of in vitro virulence factors and antifungal susceptibility pattern of gastrointestinal yeast flora of G domesticus. More studies with advanced techniques are needed to quantify the risk of spread of these potential pathogens to environment and human.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The prevalence and composition of yeast microbiota of the digestive tract vary considerably in animals and humans [1]. Gut microflora influences the health and well-being of host animals. Gut microflora can cause potentially life-threatening infections when the host’s biological homeostasis and immune resistance mechanisms are disrupted. The occurrence of different species of yeasts as natural gut residents of poultry has been documented [2, 3] but their ecological behaviour and yeast biome are poorly understood even though these birds are known to harbour pathogens with zoonotic potential [4].

There is growing concern that food derivatives from poultry sources may be an underestimated source of microorganisms with pathogenic potential. Certain species of yeasts commensal to a host species tend to have the pathogenic spectrum to others, including humans. Thus, natural yeast microbiota of animals may behave as pathogens in a suitable and conducive host. While moving between different niche and habitations, these can become vectors of virulence determinants and attain antimicrobial resistance [4, 5]. Several intrinsic factors contribute to the conversion of these organisms from harmless commensals to pathogens; the status of the host’s immune system, as well as putative virulence factors of the yeasts, play a major role in triggering infections and invading the host tissues [6]. Recently, Yuan Wu and colleagues [7] reported that fresh droppings from pigeons harboured several yeasts of medical importance and confirmed that pigeons could serve as potential reservoirs, carriers and spreaders of Cryptococcus and other medically important yeasts to humans. Psittacine birds as the source for dissemination of Trichosporon, Candida and several other yeasts to the environment and man was documented by Brilhante RS, et al. [8] who showed that these birds harboured potentially pathogenic yeasts throughout their gastrointestinal tract and in stool. Environmental pollution due to Candida, Cryptococcus, Geotrichum, Rhodotorula and Trichosporon from avian sources were in the recent past reported by Wojcik and co-workers [9], who were of the view that the presence of such organisms in the environment may pose a health risk to humans. Over and above, detection of multidrug resistant yeasts colonising the gastrointestinal tract (GIT) of synanthropic birds was of concern because these birds might be the reservoirs for transmission of drug resistant yeast infections to humans and such infections could be much severe in nature having greater potential to disseminate [7, 8]. In the above context, previous researchers reported the direct transmission of dermatomycoses to poultry workers and poultry handlers from various body parts and excreta of poultry [10,11,12,13]. Besides, another dimorphic fungus Histoplasma capsulatum, that can cause severe fatal disease in immunocompromised persons has been found in the droppings and body parts of certain avian species including chickens [14, 15] However, the role of yeast microbiota in poultry and its propensity for pathogenicity and infection is not yet well established. Undoubtedly, the close relationship between man and poultry may expose the human host to the poultry gut flora carrying virulence genes. Despite the well-known fact that domestic and wild birds may act as carriers of human pathogenic fungi, till today, clear evidence predicting poultry birds as reservoirs of drug-resistant and virulent yeasts, is lacking. It is, therefore, necessary to characterize the gastrointestinal (GI) yeast flora of poultry birds for a better understanding of the role of poultry in the possible evolution of emerging yeast infections. Considering the ever-expanding reports of opportunistic fungal infections and increasing popularity of poultry farming in Nepal, this study was conducted to characterize and evaluate in vitro virulence factors and antifungal susceptibility pattern among the GI yeast flora of both household and commercial poultry, Gallus gallus domesticus.

Methods

Sample collection

A total of 103 specimens of fresh bird droppings of adult broiler chickens (commercial G domesticus) and domesticated chickens (domesticated G domesticus) were collected from designated 45 sampling sites from commercial and local poultry breeders of Kaski district of western Nepal (Fig. 1). This region has scattered rural population of low socioeconomic background and unhygienic conditions. We selected those poultry farms that had adequate flock size, adequate husbandry practice and veterinary intervention, after obtaining factual information from the veterinarians that the reared flocks were healthy. Freshly passed poultry droppings from these sites were randomly collected with aseptic precautions, to avoid environmental contamination. The collected specimens were transported with ice packs to the microbiology laboratory of Manipal Teaching Hospital. The samples were processed within two hours of receipt in the laboratory.

Locations of Kaski district from where samples were collected (highlighted in blue) http://lgcdp.gov.np/node/363

Culture and identification

Specimens were processed as per the recommended procedures [16]. Briefly, one gram of fecal sample was loaded into tubes containing 9 ml sterile normal saline and vortexed for a minute. Subsequently, a serial tenfold dilution starting from 10−1 to 10−4 were carried out, and 100 μl aliquots were plated onto Sabouraud Dextrose Agar (SDA), supplemented with chloramphenicol (0.05 g/l; HiMedia, India). Total viable counts were determined after three days of incubation at 370 C. Colony count was expressed as CFU per gram of fecal sample. The yeast isolates were identified by conventional techniques including morphological, physiological, biochemical and vitek based identification methods [16, 17].

Trichosporon species not identifiable by conventional methods were confirmed by amplification and sequencing of the intergenic spacer 1 (IGS1) regions of rDNA [18, 19] at National Culture Collection of Pathogenic Fungi (NCCPF), Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education and Research, Chandigarh, India.

Extracellular enzymatic and hemolytic activity assays

All assays were performed as described earlier [20,21,22,23,24,25]. For the analysis of phospholipase, aspartyl proteinase, hemolysin and esterase, yeast cells were suspended in sterile normal saline at a concentration of 1 × 105 CFU/ml, and 5 μl of yeast suspension were charged on the 6 mm filter paper disc and inoculated on appropriate medium. Phospholipase activity was assayed on egg yolk medium (65 g/l SDA, 3% w/v glucose, 1 M NaCl, 5 mM CaCl2 and 8% egg yolk emulsion) [22]. Aspartyl proteinase activity was carried out on bovine serum albumin (BSA) agar (1.17% w/v yeast carbon base, 0.01% w/v yeast extract, 0.2% w/v BSA and 1.12% agar) as described previously [23]. Phospholipase and proteinase activities were determined to be positive if there was formation of precipitation halo around the fungal growth. Hemolytic activity assays were performed on SDA, incorporated with sheep blood (3% w/v glucose and 10% v/v sheep blood) [21] and were considered positive by the presence of a translucent halo around the inoculation site, viewed under transmitted light. For the assessment of DNAse activity, strains were directly spot-inoculated on DNAse test agar (HiMedia, India) and interpreted according to the instructions of the manufacturer. Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 25923 was used as a positive control in the DNAase test. Esterase activity was evaluated on Tween 80 medium (1% w/v Bacto peptone, 0.5%w/v NaCl, 0.01% w/v CaCl2, 1.5% w/v agar and 0.5% v/v Tween 80) [24]. Positivity for esterase was indicated by the presence of opaque crystals around the colony, visible against transmitted light. For all assays, the plates were incubated at 370 C for 5–7 days. Enzymatic activities (phospholipase, aspartyl proteinase, and esterase) were expressed as Pz values, which measured the diametrical ratio of the colony to halo. Activity was thus categorized as “very strong” (Pz ≤ 0.69), “strong” (Pz =0.70–0.79), “mild” (Pz = 0.80–0.89), “weak” (Pz = 0.90–0.99), or “negative” (Pz = 1.0) [25]. To test the oxidative stress tolerance, the yeast cell suspensions were treated for 1 h at 37 °C with hydrogen peroxide at the concentrations of 5, 10, 20, 40 and 50 mM. A 5 μL of the suspension was spot inoculated on SDA plates. Macro-morphology of growth (diameter and number of micro colonies) was monitored after 48-h of incubation at 37 °C and was compared to the yeast growth on control plates with no H2O2 exposure [26]. Cell surface hydrophobicity (CSH) was demonstrated as follows: 48-h old yeast culture on yeast extract peptone dextrose agar (YEPD) was adjusted to an optical density of 1.0 at 520 nm. One millilitre of xylene was added to each suspension; the test tubes were placed in a water bath at 37 °C for ten minutes to equilibrate, then vortexed for 30 s, and finally returned to the water bath for 30 min to allow the xylene and aqueous phases to separate. The absorbance of the aqueous phase was measured at 520 nm. Cell surface hydrophobicity was expressed as the percentage reduction in optical density of the test suspension compared with control. The greater the change in absorbance, the more was the hydrophobicity [20]. Activity was thus categorized as “very strong” (>30%), “strong” (20–29.9%), “mild” (10–19.9%), “weak” (0.1–9.99%), or “negative” (< 0.1%). All assays were performed in triplicate on separate occasions.

Biofilm assay

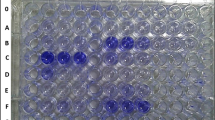

The yeast isolates grown overnight on YEPD broth at 370 C were harvested, washed twice with sterile PBS and then re-suspended in YEPD broth, to a concentration of 105 CFU/ml. Biofilms were formed by pipetting 200ul of the standardized cell suspension into commercially available pre-sterilized polystyrene 96 wells tissue culture plates (HiMedia, India) and incubating at 370 C for 90 min (adhesion phase). Wells were, then, washed twice with sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) to remove non-adherent cells and then refilled with 200 μl of sterile YEPD broth, re-incubated for further 48 h at 37 °C, replacing the medium at 24 h of incubation (biofilm formation phase). At the end of the whole process, the medium was aspirated and non-adherent cells were removed by washing the wells thrice in PBS. Known biofilm producer and non-biofilm producer Candida strains served as positive and negative controls respectively.

Quantification of biofilm

Quantitative biofilm assessments were performed by crystal violet staining method (staining for biomass) [27] and colorimetric measurement based on sodium 39-[1-(phenylamino-carbonyl)-3,4-tetrazolium]-bis (4-methoxy-6-nitro) benzene sulfonic acid hydrate (XTT) reduction (metabolic activity) as previously described [28].

Antifungal susceptibility testing against planktonic and biofilm-forming cells

Assay conditions of the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) broth micro dilution method [29] were adopted to evaluate the response of planktonic fungal cells to the following drugs: fluconazole (FLC), voriconazole (VRC), caspofungin (CFG) and amphotericin B deoxycholate (AMB). Antifungal compounds were obtained as pure powders from the manufacturer, Sigma-Aldrich Laborchemikalien GmbH, Germany. Candida parapsilosis ATCC 22019 and Candida krusei ATCC 6258 were used as controls. Minimum Inhibitory Concentrations (MIC) of the drugs on planktonic cells were determined by visual readings after 48 h of incubation based on the lowest concentration capable of inhibiting 50% of cell growth for azoles and 100% for AMB and CFG.

Susceptibility tests for biofilm-forming cells were performed following the protocol previously described by Melo et al. [30]. Biofilms were grown for 24 h before replacement of the medium with fresh YEPD supplemented with the antifungals at the following concentrations: FLC (2–512 μg/ml), CFG (0.5-64 μg/ml), VRC (0.5–64 μg/ml) and AMB (0.5–64 μg/ml). Following a further incubation for 48 h, biofilms were quantified using the XTT reduction assay. For the XTT reduction assay, a solution containing 200 ml PBS with 12 ml 5:1 [XTT (1 mg/ml): Menadione (0.4 mM)] was used. The plate was incubated for 2 h at 37 °C to allow XTT metabolization. Thereafter 100 μl of this solution was transferred to another microplate, and the absorbance was read spectrophotometrically at (492 nm/620 nm [read/reference]). Minimum Inhibitory Concentrations of biofilm cells was determined as the lowest concentration of antifungal agent causing a 100% reduction in metabolic activity.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive and inferential statistics were used for analyzing the data entered in Microsoft Excel 2010 by Statistical Analysis System (SAS) and Origin Pro 2016. Variation of colony count (CFU/g) in different yeast species was obtained by using minimum, maximum, mean and box plot. Descriptive analysis was performed to determine the frequency of the virulence factors viz., biofilm, DNase, hemolysin, esterase, aspartyl proteinase, phospholipase, CSH, SOD among yeast isolates. Spearman correlation was used to correlate various virulence factors. In vitro activity of antifungal drugs against planktonic cells, and biofilm cells were estimated with geometrical mean, 90th percentile, 50th percentile, and range. The “p” value of <0.01 was considered statistically significant.

Results

A total of 103 poultry dropping specimens were collected from 42 commercial and 61 local breeders of Kaski district of western Nepal. Twelve different yeast species were grown on 84 samples (81.5%), 43 yeast strains were isolated from broiler chickens and 45 yeast strains were isolated from domesticated chickens. As depicted in Table 1, the isolates comprised of 29 (33%) Debaryozyma hansenii (Candida famata), 12 (13.6%) Sporothrix catenata (C. ciferrii), 10 (11.4%) C. albicans, 8 (9.1%) Diutnia catenulata (C. catenulate), 6 (6.8%) C. tropicalis, 3 (3.4%) Candida acidothermophilum (C. krusei), 2 (2.3%) C. pintolopesii, 1 (1.1%) C. parapsilosis, 9 (10.2%) Trichosporon spp. (T. moniliiforme, T. asahii), 4 (4.5%) Geotrichum candidum, 3 (3.4%) Cryptococcus macerans and 1 (1%) Cystobasidium minuta (Rhodotorula minuta).

Fungal burden (CFU/g) in the poultry GIT

Colony counts [mean, median and range interval (minimum- maximum) CFU/g] have been depicted in Fig. 2 and Table 1. The overall median CFU for the 88 yeast isolates was 0.5X107 CFU/g (interquartile range (IQR) 0.5X107). It was interesting to note that both mean colony count and colony count range for C. albicans (mean 5 × 106 CFU/g, range 2 × 106- 7 × 106) were comparable to those for D. hansenii (mean 5 × 106 CFU/g, range 1.1 × 106–1.2 × 106) and C. acidothermophilum (mean: 3 × 106 CFU/g, range: 1.1 × 106-5 × 106); but were found to be much lower in comparison to the respective values for other yeasts and non albicans Candida species (D. catenulata, mean: 6.6 × 106, range: 2.7 × 106–1.2 × 107; C. tropicalis, mean:1.1 × 107, range:3 × 106–2.3 × 107; S. catenata, mean: 9 × 106, range:3 × 106–1.9 × 107; C. pintolopesii, mean; 9.5 × 106, range: 3 × 106–1.6 × 107, Cryptococcus macerans, mean: 8.3 × 106, range: 3 × 106–1.6 × 107). The overall fungal burdens in the case of C. pintolopesii, C. tropicalis, and C. ciferrii were, however, higher compared with C. albicans, C. parapsilosis, C. krusei and other yeasts, such as Geotrichum candidum, Trichosporon species. Such statistical comparison could not be drawn in cases of C. parapsilosis and C. minuta as those were single isolates.

A box plot representation of the CFU/g median values of different yeasts isolated from Gallus gallus domesticus. Legend: 1: C. albicans, 2: D. catenulate (C catenulate), 3: C. tropicalis, 4: D. hansenii (C. famata), 5: S. catenata (C ciferrii), 6: C. pintolopesii, 7: Cryptococcus macerans, 8: Trichosporon spp. 9: G candidum 10: Cystobasidium minuta (Rhodotorula minuta), 12: C parapsilosis, 13: C. acidothermophilum (C. krusei)

Isolates were able to produce hydrolytic enzymes and other phenotypic virulence factors

Out of 88 yeast isolates, 38 isolates (43.1%) were biofilm producers in term of both biomass production and metabolic activity of sessile cells. Rhodotorula minuta, C. pintolopesii did not show in vitro biofilm activity. Most of the strains (56.8%; 50/88) displayed high CSH and superoxide dismutase (46.3%; 38/82) activity. Similarly, high to medium proteinase (28.4%) and esterase activity (26.1%) were observed among the isolates. DNase was detected in 11 isolates (12.5%). None of the isolates was positive for hemolysin. Similarly, the majority of yeast species (95.5%) did not produce any detectable phospholipase. The results for virulence determinants are summarized in Table 1.

Observation of statistical relationships between the occurrences of different virulence factors

Overall, the relationship found among the different virulence factors of the yeast isolates was minimal (Table 2). However, an observable relationship was detected between the Pz values of phospholipase with Pz value of proteinase; CSH percentage with Pz values Esterase and Pz values phospholipase with Pz values DNAs (Spearman’s correlation coefficient of 0.407 (p = 0.000), 0.237 (p = 0.026), 0.240 (p = 0.024) respectively).

Biofilm-forming cells had higher MIC values against antifungal agents

Table 3 summarizes the planktonic MIC50, MIC90, and MIC ranges (μg/ml) and the geometric mean MICs (GM) obtained for the 12-yeast species against fluconazole, amphotericin B, voriconazole, and caspofungin. Minimum Inhibitory Concentration values of fluconazole, amphotericin B were found to be higher for all fungal isolates tested. The respective values for the biofilm cells were noted to be comparatively higher than those detected in the planktonic cells (Table 3), suggesting thereby that biofilm in an in vivo situation could be less amenable to a broad range of antifungal agents in clinical use. Table 4 shows the MIC values for all antifungals tested against biofilm cells.

Discussion

It is well known that opportunistic fungal infections were one of the emerging problems globally [31, 32]. Organisms that were once relegated as innocuous inhabitants of the environment have now emerged as potential opportunistic pathogens with the ability to colonize and infect susceptible hosts. In the 1980s, the aetiology of invasive yeast infection in humans was restricted only to those caused by C albicans. In the recent years, non-albicans Candida species accounted for >50% of invasive fungal infections [33]. Candida bloodstream infections were also recorded to be quite high due to non- albicans Candida species, accounting for more than 28% of cases [34]. Over and above, invasive infections due to other rare yeasts, such as Trichosporon spp., Geotrichum spp., Cryptococcus other than C neoformans and Rhodotorula spp. were recently reported [35,36,37,38]. A few studies suggested that GI colonization could be one of the potential sources for deep-seated yeast infections [39, 40].

Many animals including poultry were in the recent past, recognized as carriers of livestock-associated pathogens that could on a number of occasions cause disease in the human host [41, 42]. The present study demonstrated diverse generic groups of yeasts with high MIC values. Prevalence of yeast flora in the digestive tract of these birds revealed higher colonization by Candida other than C albicans. This is contrary to the observation of Shokri H et al. [42] and Lord et al. [3] who noticed the highest prevalence of C albicans among the gut flora of broiler chickens. The fungal burden as determined by our study was as high as 0.5 × 107 CFU/g in terms of statistical mean values. Comparatively, the much lower fungal burden was documented in similar other studies [42]. Such variations in the gut colonisation by different Candida species as observed could be attributed to dietetic and environmental factors, hygienic conditions, and other ecological factors at different geographical locations [43]. The birds under particular combinations of diet or under stress could have higher level of corticosteroids that would affect the immune system resulting in higher gut colonisation [43,44,45]. It is difficult to predict which factors the present flock had been exposed to. High fungal burden in the gut microbiota of the poultry in our study suggests greater chance of dissemination of the gut flora to other poultries, human beings and their environments [8, 46]. This proposition is substantiated by other studies [7,8,9].

Colonisation rates of Trichosporon spp., G candidum, Rhodotorula spp. and S cerevisiae was shown to be 5.5%, 4.6%, 3.3% and 0.5% respectively, in a recent study conducted by Shokri et al. [42]. Our results documented higher colonisation rates of Trichosporon spp., Geotrichum candidum, and Rhodotorula minuta as 10.2%, 4.5%, and 1.1% respectively. This difference could be due to the more sensitive and specific molecular techniques and automated identification systems deployed in our study. It was interesting to find Cryptococcus macerans among the gut flora of three of the birds. Cryptococcus neoformans is known to colonise the GIT of many avian species, especially pigeons with potential threat to the human from the dried and desiccated droppings of these birds [7]. The zoonotic potential of non-neoformans Cryptococcus species from poultry gut flora is not well studied. Detecting these organisms in the gut flora raises the possibility of colonisation by C. neoformans as well. This plausibility calls for strict vigilance.

Most of the isolated organisms in the present study are documented human pathogens with evolving zoonotic potential. Virulence factors play a significant role in colonising the host evading the host defence there by contributing to the pathogenicity. These include the ability to adhere to surfaces and secretion of various hydrolytic enzymes [47, 48]. In the present study, 46.3% of the isolates produced SOD, and 56.8% possessed CSH. This is in agreement with the observations of earlier workers who proposed that CSH was a prerequisite for biofilm formation [49]. We observed that, 43.1% of the total yeasts and 39.4% Candida species were biofilm producers. Among all the biofilm producing Candida species, non-albicans Candida species alone accounted for 82.1% (23/28). As has been reported, biofilm formation on indwelling medical devices, especially by Candida species and Trichosporon species, is increasingly recognized for evading the host immunity and often leading to treatment failure [3, 50,51,52,53,54]. Detecting such high rate of biofilm producing non-albicans Candida is of utmost significance.

Variation in the production of hydrolytic enzymes among different species of yeasts was observed; most of them being able to exhibit in-vitro high-level CSH and SOD. High degree of positive concordance among different phenotypic enzymatic markers was not detected despite an observable relationship of phospholipase with proteinase, CSH with esterase and phospholipase with DNAs. Samaranayake et al. [20], noted the positive correlation between CSH and adhesion of C. krusei isolates onto HeLa cells and were of the view that this attribute along with other cell surface features might determine the hierarchy of virulence among different Candida species. Despite lack of significant correlation between different virulence markers as stated above, production of biofilm could be singled out as the sole pathogenic biomarker that was exhibited by 43.1% of all yeasts including 39.4% of Candida species. This supports the recent proposition of the role of biofilm in pathogenicity of Candida [50, 51]. All phenotypic characters may not necessarily be attributes of pathogenicity of Candida and other yeasts.

Another virulence property of fungal pathogens i.e. drug resistance, has come to the forefront only very recently [55,56,57].We recovered yeast isolates with high MICs for fluconazole and amphotericin B, and a narrow range of MIC against caspofungin and voriconazole. In addition, the MIC50 values of C. krusei and C. tropicalis for fluconazole were marginally higher than those reported in the clinical setting [58, 59]. Very high MIC 90 values for almost all Candida isolates as shown in this study are of major concern. It is a common practice in commercial poultry to add growth promoters and antimicrobials to poultry feed to protect the poultry from various diseases. We hypotheticise that these practices could be contributory towards such high level of drug resistance. At the same time, the intrinsic resistance of various yeasts to these antifungal agents cannot be overlooked. It is important to determine the exact sources of resistance development in poultry yeasts in order to develop strategies to arrest their propagation. It warrants careful monitoring as these drug-resistant strains could be of human origin [60] that might have evolved resistance due to antimicrobial pressure and subsequently disseminated to the domesticated flocks. It is difficult to conclusively prove this proposition, without demonstration of shared phenotypic and/or genotypic markers between human and poultry isolates. This necessitates further molecular studies.

It is well known that horizontal gene transfer among yeasts and zoonotic transmission of yeasts to humans is rare. Our study supports the hypothesis that poultry birds could be potential reservoirs of virulent and drug-resistant yeasts. Based on our and other reports [2, 3, 5, 8, 9, 42,43,44,45] we propose further studies to evaluate in-vivo virulence and clonal similarities between poultry and human isolates. Such studies will determine the potential of poultry yeasts to migrate to humans and vice versa.

Conventional culture based methods are beset with challenges in recovering the large spectrum of colonizing yeast in poultry gut flora. Advanced culturing methodologies and sequencing technology may be helpful in profiling both cultivable and non-cultivable mycobiome in poultry.

Conclusion

The present work extends the current understanding of phenotypic characteristics of normal gastrointestinal yeast flora of G domesticus by providing information on in vitro virulence factors and antifungal susceptibility pattern. It is, therefore, reasonable that future studies should pay much attention in assessing the possible risk of transmission to humans or animals due to the dissemination of yeasts via food chain or environmental routes.

Abbreviations

- AMB:

-

Amphotericin B deoxycholate

- ATCC:

-

American Type Culture Collection

- BSA:

-

Bovine Serum Albumin

- CFG:

-

Caspofungin

- CFU:

-

Colony forming units

- CLSI:

-

Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute

- CSH:

-

Cell Surface Hydrophobicity

- DNAse:

-

Deoxyribonuclease

- FLC:

-

Fluconazole

- GIT:

-

Gastrointestinal tract

- IGS1:

-

Intergenic spacer 1

- IQR:

-

Interquartile range

- MIC:

-

Minimum Inhibitory Concentration

- PBS:

-

Phosphate Buffered Saline

- rDNA:

-

Ribosomal DNA

- SAS:

-

Statistical Analysis System

- SDA:

-

Sabouraud Dextrose Agar

- SOD:

-

Superoxide Dismutase

- VRC:

-

Voriconazole

- Vs:

-

Versus

- XTT:

-

sodium 39-[1-(phenylamino-carbonyl)-3,4-tetrazolium]-bis (4-methoxy-6-nitro) benzene sulfonic acid hydrate

- YEPD:

-

Yeast Extract Peptone Dextrose Agar

References

Gabriel I, Mallet S, Sibille P. Digestive microflora of bird: factors of variation and consequences on bird. INRA Prod Anim. 2005;18:309–22.

Dynowska M, Kisicka I. Fungi isolated from selected birds potentially pathogenic to humans. Acta Mycol. 2005;40:141–7.

Lord AT, Mohandas K, Somanath S, Ambu S. Multidrug resistant yeasts in synanthropic wild birds. Ann Clin Microbiol Antimicrob. 2010;9:11. doi:10.1186/1476-0711-9-11.

Dynowska M, Kisicka I. Participation of birds in the circulation of pathogenic fungi descend from water environments: a case study of two species of Charadriiformes birds. Ecohydrol Hydrobiol. 2005;5:173–8.

Tsiodras S, Kelesidis T, Kelesidis I, Bauchinger V, Falagas ME. Human infections associated with wild birds. J Inf Secur. 2008;56:83–98.

Tsai P, Chen Y, Hsu P, Lan C. Study of Candida albicans and its interactions with the host: a mini review. Biomedicine. 2012;3:51–64.

Wu Y, Du PC, Li WG, Lu JX. Identification and molecular analysis of pathogenic yeasts in droppings of domestic pigeons in Beijing, China. Mycopathologia. 2012;174(3):203–14. 10.1007/s11046-012-9536-9.

Brilhante RS, Castelo-Branco DS, Soares GD, Astete-Medrano DJ, Monteiro AJ, Cordeiro RA, Sidrim JJ, Rocha MF. Characterization of the gastrointestinal yeast microbiota of cockatiels (Nymphicus hollandicus): a potential hazard to human health. J Med Microbiol. 2010;59:718–23. doi:10.1099/jmm.0.017426-0.

Wójcik A, Kurnatowski P, Błaszkowska J. Potentially pathogenic yeasts from soil of children's recreational areas in the city of Łódź (Poland). Int J Occup Med Environ Health. 2013;26(3):477–87. doi:10.2478/s13382-013-0118-y.

Amani SA. Occupational Dermatoses among poultry slaughterhouse Workers in Sharkia Governorate: an epidemiological study. Curr Sci Int. 2013;2(2):42–7.

Quandt SA, Schulz MR, Feldman SR, Vallejos Q, Marin A, Carrillo L, Arcury TA. Dermatological illnesses of immigrant poultry processing workers in North Carolina. Arch Environ Occup Health. 2005;60(3):165–9.

Government Accountability Office. Workplace safety and health: safety in the meat and poultry industry, while improving, could be further strengthened. Washington, DC: US Government Accountability Office, 2005 (GAO-05-96).

Human Rights Watch. Blood, Sweat, and Fear: Workers’ Rights in US Meat and Poultry Plants. New York: Human Rights Watch; 2004. https://www.hrw.org/report/2005/01/24/blood-sweat-and-fear/workers-rights-us-meat-and-poultry-plants. Accessed 24 Jan 2005.

Salfelder K, Schwarz J. Histoplasma capsulatum and chickens. Mycoses. 1967;10:337–50. doi:10.1111/j.1439-0507.1967.tb02886.x.

Canadian Centre for Occupational Health & Safety: Histoplasmosis. https://www.ccohs.ca/oshanswers/diseases/histopla.html. Accessed 1 July 2013.

Collier L, Balows A, Sussman M. Topley & Wilson’s Microbiology and Microbial Infections. 9th ed, vol. 4. Arnold, London, Sydney, Auckland, New York: Hodder Education Publishers; 1998. pp. 1337–1338.

Rippon JW: laboratory mycology in Rippon JW(ed): Medical Mycology. Candidiasis and the pathogenic yeasts, Philadelphia, WB Saunders, 1988,484–536.

Sambrook J, Russell DW. Molecular cloning: a laboratory manual. New York, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 2001.

Sugita T, Nakajima M, Ikeda R, Matsushima T, Shinoda T. Sequence analysis of the ribosomal DNA intergenic spacer 1 regions of Trichosporon species. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40:1826–30.

Samaranayake YH, Dassanayake RS, Jayatilake JA, Cheung BP, Yau JY, Yeung KW, et al. Phospholipase B enzyme expression is not associated with other virulence attributes in Candida albicans isolates from patients with human immunodeficiency virus infection. J Med Microbiol. 2005;54:583–93.

Luo G, Samaranayake LP, Yau JY. Candida species exhibit differential in vitro hemolytic activities. J Clin Microbiol. 2001;39(8):2971–4.

Price MF, Wilkinson ID, Gentry LO. Plate method for detection of phospholipase activity in Candida albicans. Sabouraudia. 1982;20:7–14.

Chakrabarti A, Nayak N, Talwar P. In vitro proteinase production by Candida species. Mycopathologia. 1991;114(3):163–8.

Slifkin M. Tween 80 opacity test responses of various Candida species. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38(12):4626–8.

Tosun I, Akyuz Z, Guler NC, Gulmez D, Bayramoglu G, Kaklikkaya N, et al. Distribution, virulence attributes and antifungal susceptibility patterns of Candida parapsilosis Complex strains isolated from clinical samples. MedMycol. 2013;51(5):483–92.

Aleksandra B, Beata S , Marzena WS ,Bartłomiej M, Anna S , Dariusz J, et.al. Saponins of Trifolium spp. aerial parts as modulators of Candida albicans virulence attributes. Molecules 2014;19:10601-10617; doi:10.3390/molecules190710601.

Iturrieta-González IA, Padovan AC, Bizerra FC, Hahn RC, Colombo AL. Multiple species of Trichosporon produce Biofilms highly resistant to Triazoles and Amphotericin B. PLoS One. 2014;9(10):e109553. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0109553.

Di Bonaventura G, Pompilio A, Picciani C, Iezzi M, D’Antonio D, Piccolomini R. Biofilm formation by the emerging fungal pathogen Trichosporon asahii: development, architecture, and antifungal resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2006;50(10):3269–76. doi:10.1128/AAC.00556-06.

CLSI. Reference method for broth dilution antifungal susceptibility testing of yeasts M27-A3; approved standard – Third Edition. Wayne, PA: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute;2008.

Melo AS, Bizerra FC, Freymuller E, Arthington-Skaggs BA, Colombo AL. Biofilm production and evaluation of antifungal susceptibility amongst clinical Candida spp. isolates, including strains of the Candida parapsilosis Complex. Med Mycol. 2011;49:253–62.

Marisa HM, José AD, Samuel AL. Emerging opportunistic yeast infections. Lancet Infect Dis. 2011;11(2):142–51.

Subramanya Supram H, Gokhale S, Chakrabarti A, Rudramurthy SM, Gupta S, Honnavar P. Emergence of Magnusiomyces capitatus infections in western Nepal. Med Mycol. 2016;54(2):103–10. doi:10.1093/mmy/myv075.

Pappas PG, Rex JH, Lee J, et al. A prospective observational study of candidemia: epidemiology, therapy, and influences on mortality in hospitalized adult and paediatric patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37:634–43.

Oberoi JK, Wattal C, Goel N, Raveendran R, Datta S, Prasad K. Non-albicans Candida species in blood stream infections in a tertiary care hospital at New Delhi India. Indian J Med Res. 2012;136(6):997–1003.

Picard M, Cassaing S, Letocart P, Verdeil X, Protin C, Chauvin P, et al. Concomitant cases of disseminated Geotrichum clavatum infections in patients with acute myeloid leukemia. Leuk Lymphoma. 2014;55(5):1186–8. doi: 10.3109/10428194.2013.820290

Ramya TG. Sabitha baby, Geetha RK pulmonary infection by Geotrichum candidum. Int J Adv Med. 2014;1(2):171–2. doi:10.5455/2349-3933.ijam20140816.

Khawcharoenporn T, Apisarnthanarak A, Mundy LM. Non-neoformans Cryptococcal infections: a systematic review. Infection. 2007;35:51. doi:10.1007/s15010-007-6142-8.

Wirth F, Goldani LZ. Epidemiology of Rhodotorula: an emerging pathogen. Interdiscip Perspect Infect Dis. 2012;2012:465717. doi:10.1155/2012/465717.

Colombo AL, Padovan AC, Chaves GM. Current knowledge of Trichosporon spp. and Trichosporonosis. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2011;24:682–700.

Cho O, Matsukura M, Sugita T. Molecular evidence that the opportunistic fungal pathogen Trichosporon asahii is part of the normal fungal microbiota of the human gut based on rRNA genotyping. Int J Infect Dis. 2015;39:87–8. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2015.09.009

Callaway TR, Edrington TS, Anderson RC, Byrd JA, Nisbet DJ. Gastrointestinal microbial ecology and the safety of our food supply as related to Salmonella. J AnimSci. 2008;86(Suppl.14):E163–72. doi:10.2527/jas.2007-0457.

Shokri H, Khosravi AR. Nikaein. A comparative study of digestive tract mycoflora of broilers with layers. Int. JVetRes. 2011;5(1):1–4.

Balseiro A, Espi A, Marquez I, Perez V, Ferreras MC, Garcia Marin JF, et al. Pathological features in marine birds affected by the prestige’s oil spill in the north of Spain. J Wildlife Dis. 2005;41:371–8.

Blanco G, Lemus JA, Grande J, Gangoso L, Grande JM, Donázar, J.A. Geographical variation in cloacal microflora and bacterial antibiotic resistance in a threatened avian scavenger in relation to diet and livestock farming practices. Environ Microbiol 2007; 9: 1738-1749.

Deem SL. Fungal diseases of birds of prey. Vet Clin NorthAm ExoticAnim Pract. 2003;6:363–76.

Seyedmousavi S, Guillot J, Tolooe A, Verweij PE, de Hoog GS. Neglected fungal zoonoses: hidden threats to man and animals. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2015 May;21(5):416–25. doi:10.1016/j.cmi.2015.02.031.

Ells R, Kilian W, Hugo A, Albertyn J, Kock JL, Pohl CH. Virulence of south African Candida albicans strains isolated from different clinical samples. Med Mycol. 2014;52(3):246–53. doi:10.1093/mmy/myt013.

Cafarchia C, Romito D, Coccioli C, Camarda A, Otranto D. (2008) ‘Phospholipase activity of yeasts from wild birds and possible implications for human disease’. Med Mycol. 2008;46(5):429–34. doi:10.1080/13693780701885636.

Silva-Dias A, Miranda IM, Branco J, Monteiro-Soares M, Pina-Vaz C, Rodrigues AG. Adhesion, biofilm formation, cell surface hydrophobicity, and antifungal planktonic susceptibility: relationship among Candida spp. Front Microbiol. 2015;6:205. doi:10.3389/fmicb.2015.00205.

Jigar VD, Aaron PM, David RA. Fungal Biofilms, drug resistance, and recurrent infection. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2014;4:a019729. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a019729.

Nobile CJ, Johnson AD. Candida albicans Biofilms and human disease. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2015;69:71–92. doi:10.1146/annurev-micro-091014-104330.

Sachin C, Deorukhkar SS, Stephen M. Non-albicans Candida infection: an emerging threat. Interdiscip Perspect Infect Dis. 2014;2014:615958. doi:10.1155/2014/615958.

Snydman DR. Shifting patterns in the epidemiology of nosocomial Candida infections. Chest. 2003 May;123(5 Suppl):500S–3S.

Beyda ND, Chuang SH, Alam MJ, Shah DN, Ng TM, McCaskey L, et al. Treatment of Candida famata bloodstream infections: case series and review of the literature. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2013;68(2):438–43. doi:10.1093/jac/dks388.

Vandeputte P, Ferrari S, Coste AT. Antifungal resistance and new strategies to control fungal infections. Int J Microbiol. 2012;2012:713687. doi:10.1155/2012/713687.

Radhouani H, Silva N, Poeta P, Torres C, Correia S, Igrejas G. Potential impact of antimicrobial resistance in wildlife, environment, and human health. Front Microbiol. 2014;5;5:23. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00023.

Perron GG, Quessy S, Bell G. A reservoir of drug-resistant pathogenic bacteria in asymptomatic hosts. PLoS One. 2008;3(11):e3749. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0003749.

Desnos-Ollivier M, Robert V, Raoux-Barbot D, Groenewald M, Dromer F. Antifungal susceptibility profiles of 1698 yeast reference strains revealing potential emerging human pathogens. PLoS One. 2012;7(3):e32278. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0032278.

Amran F, Aziz MN, Ibrahim HM, Atiqah NH, Parameswari S, Hafiza MR, et al. In vitro antifungal susceptibilities of Candida isolates from patients with invasive candidiasis in Kuala Lumpur hospital. Malaysia J Med Microbiol. 2011 Sep;60(Pt 9):1312–6. doi:10.1099/jmm.0.027631-0.

Messenger AM, Barnes AN, Gray GC. Reverse Zoonotic disease transmission (Zooanthroponosis): a systematic review of seldom-documented human biological threats to animals. PLoS One. 2014;9(2):e89055. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0089055.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge the owners of poultry farms who provided the permission to collect the specimens. We thank Dr. Arunaloke Chakrabarti and Dr. MR Shivaprakash, Centre of Advance Research in Medical Mycology & WHO Collaborating Centre, Postgraduate Institute of Medical Education & Research, Chandigarh, India, for genotyping of the isolates. We extend our special thanks to Manipal Teaching Hospital, Pokhara, Nepal, for providing the facility to carry out the study.

Funding

The authors have not received any funding from any agency to support the work presented in this submission.

Availability of data and materials

Data sharing not applicable to this article as no datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Authors’ contributions

HSS conceived and designed the study, collected and processed the specimens, undertook lytic compounds activity assay, antifungal sensitivity testing, data analysis and wrote the manuscript. NKS and BPB contributed towards lytic compounds activity assays and antifungal sensitivity testing. DH contributed towards specimen collection and phenotypic identification of yeasts. PYP contributed towards the identification of yeasts and manuscript preparation. BS assisted with the statistical analysis. NN contributed towards the interpretation of the antifungal susceptibility tests, and critical evaluation of the manuscript. IB and SG contributed towards distilling the material and manuscript preparation. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests. The abstract of this manuscript was presented at 17th International Congress on Infectious Diseases which held in Hyderabad, India, March 2016.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The research proposal was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee, Manipal Teaching Hospital, Pokhara, Nepal. Reference number: MEMG/IRC/GA30/11/2014. The research was conducted in accordance with the latest version of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Subramanya, S.H., Sharan, N.K., Baral, B.P. et al. Diversity, in-vitro virulence traits and antifungal susceptibility pattern of gastrointestinal yeast flora of healthy poultry, Gallus gallus domesticus . BMC Microbiol 17, 113 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12866-017-1024-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12866-017-1024-4