Abstract

Background

Our previous research on the diversity of microbiota in the endotracheal tubes (ETTs) of neonates in the neonatal intensive care unit found that Pseudomonas aeruginosa (P. aeruginosa) and Streptococcus mitis (S. mitis) were the dominant bacteria on the ETT surface and the existence of S. mitis could promote biofilm formation and pathogenicity of P. aeruginosa. Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4), which has been widely detected on the surface of airway epithelial cells, is the important component of the innate immune system. Therefore, we hypothesized that the co-existence of these two bacteria might impact the host immune system through TLR4 signaling.

Results

S. mitis rarely caused inflammation, whereas P. aeruginosa caused the most severe inflammation accompanied by increases in the number of inflammatory cells, interleukin (IL)-6 and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α expression, and total cell counts in BALF (p < 0.05). In the PAO1 + S. mitis group, moderate inflammation, reduced IL-6 and TNF-α protein levels, and decreased total cell counts were observed. Additionally, levels of these indicators were decreased lower in TLR4-deficient mice than in wild-type mice (p < 0.05).

Conclusions

Our results demonstrated that infection with S. mitis together with P. aeruginosa could alleviate lung inflammation in acute lung infection mouse models possibly via the TLR4 signaling pathway.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP) is a common device-related infection in neonatal intensive care units (NICUs), and it is associated with high morbidity and mortality as well as increased antibiotic resistance and high economic costs [1, 2]. Our previous research demonstrated that Pseudomonas aeruginosa (P. aeruginosa) and Streptococcus mitis (S. mitis) were the most dominant microbes on the surface of neonatal endotracheal tubes (ETTs) [3, 4]. In addition, the co-existence of S. mitis from the oral microbiome and the opportunistic pathogen P. aeruginosa on the same ETT may play a crucial role in biofilm formation. Khosravi et al. found that S. mitis produced and released a tenovin 6-like molecule that induced growth inhibition and coccoid conversion of Helicobacter pylori cells [5]. Moreover, recent discoveries regarding the pathogenesis of VAP has found an interesting phenomenon in which autoinducer-2 produced by S. mitis can act as an important molecule to promote P. aeruginosa biofilm formation and to increase proinflammatory cytokine secretion in endotracheal intubation rat models [6]. Given that S. mitis is the most abundant bacteria of the normal human oral flora and rarely causes diseases, we questioned whether S. mitis could also modulate the pathogenicity of P. aeruginosa in acute lung infection. If so, how does this co-existence impact the immune system of the host and what is the possible mechanism in acute lung infection?

Toll-like receptors (TLRs), one of the most important receptor families of the innate immune system, can recognize pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), including microbial products, and play an important role in the immune response [7, 8]. At present, 11 TLRs have been identified in humans [9]. Recent studies have confirmed that TLR2, 4, 5, and 9 play pivotal roles in the response to bacterial infections [10]. TLR4 is a receptor for lipopolysaccharide (LPS), an important cell wall component of gram-negative bacteria. Through ligand binding, TLR4 recruits signaling adaptors and initiates signaling cascades, which results in the activation of nuclear factor (NF)-κB and the release of inflammatory cytokines, such as interleukin (IL)-6 [11] and tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α [12]. Moreover, airway epithelial cells are believed to contribute to the inflammatory response in the lung, and TLR4 has been widely detected on the surface of airway epithelial cells as well as cells of the myeloid lineage, such as macrophages and neutrophils [13, 14]. Some studies have reported that TLR4-deficient mice show increased lung inflammation and higher bacterial load, and TLR4 signaling may have a critical function in the fine tuning of inflammation during chronic mycobacterial infection [15]. Therefore, we hypothesized that TLR4 signaling might participate in the response to acute lung infection.

Based on our previous findings that P. aeruginosa and S. mitis are the dominant bacteria in the mixture of organisms causing lung infections, these two bacteria were selected for the present study. The aim of our study was to explore the relationship between P. aeruginosa and S. mitis in lung infection and ascertain their roles in the immune response. After acute lung infection mouse models were established, lung bacteriological and histopathological examinations were performed, and total cell counts and levels of related cytokines in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid (BALF) were determined.

Methods

Bacteria and growth conditions

P. aeruginosa strain PAO1 (ATCC27853) and S. mitis (ATCC49456) were used in our study. PAO1 was kindly provided by Professor Li Shen (Institute of Molecular Cell and Biology, New Orleans, LA, USA). S. mitis was purchased from American Type Culture Collection. The bacterial strains were both cultured overnight in brain-heart infusion (BHI) broth. The S. mitis strain was grown at a neutral pH at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere. The PAO1 strain was grown at 37 °C on an orbital shaker at 200 rpm. Overnight-grown cultures of the strains were standardized to 0.2 (OD600), and then diluted to a working concentration of OD600 = 0.1, if necessary.

Animals

Forty C57BL/6 mice (6–8 weeks, 18–20 g) were obtained from the Experimental Animal Center of Chongqing Medical University and housed in the Laboratory Animal Center at the Children’s Hospital of Chongqing Medical University. Twenty TLR4-deficient mice (C57BL/10ScNJ) were obtained from the Key Laboratory of Diagnostic Medicine Designated by the Ministry of Education at Chongqing Medical University. TLR4 gene expression was determined by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) before the experiments to confirm the reliability of the TLR4-deficient mice. The experimental protocol was approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Chongqing Medical University.

Acute lung infection mouse models

Twenty wild-type mice were randomly divided into four groups (n = 5/group) treated with: PAO1 (OD600 = 0.1, 1 × 108 CFU/mL, 50 μL), S. mitis (OD600 = 0.1, 1 × 108 CFU/mL, 50 μL), PAO1 + S. mitis (OD600 = 0.2, 2 × 108 CFU/mL, 25 μL + 25 μL), or phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (control group, 50 μL). Twenty TLR4-deficient mice were divided into the same treatment groups. Additionally, another 20 wild-type mice were subjected to the same treatments and used to estimate the bacterial burden, in order to confirm successful establishment of the acute lung infection mouse models.

The mouse models of acute lung infection were established as previously described with some modifications [16]. Briefly, mice were anesthetized with an intraperitoneal injection of chloral hydrate (0.02 mL/g) before tracheotomy. Then they were infected with an intratracheal instillation of 50 μL of bacterial suspension and kept upright in standing posture for 10 s to ensure the bacteria were fully delivered to the lung tissues. Finally, the trachea and skin were sutured. The mice were kept for 48 h before sacrificed.

Lung bacteriological and histological examinations

The whole lung of each mouse (n = 5 mice/group) was homogenized in 1 mL PBS and then serially diluted. A 50-μL sample from each tissue homogenate specimen was cultured quantitatively on Columbia sheep blood agar plates overnight at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 atmosphere, and then the colonies were counted to estimate the number of colony-forming units (CFU). The right lungs of the other five mice in each group were fixed in 10% formalin buffer for 48 h, embedded in paraffin, dehydrated, cut into 5-μm slices, and stained with hematoxylin-eosin (H&E) for histopathological examination [17]. Images were obtained using light microscopy (Nikon eclipse 55i, Japan).

Total cell counts and cytokine analyses in BALF

The left lungs were lavaged and collected with 1 mL PBS. The fluid was instilled and withdrawn three times, and then the total cell counts in the BALF were determined using a cell counter (Countstar, Beijing, China). BALF samples were centrifuged at 3000 g and 4 °C for 5 min. The concentrations of pro-inflammatory cytokines TNF-α and IL-6 in the BALF supernatant were determined using mouse cytokine enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) kits (Beijing 4A Biotech Co., Ltd., Beijing, China) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were carried out using SPSS 22.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to identify significant differences among all groups. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Bacterial CFU in lung tissues

To confirm the successful establishment of the acute lung infection mouse models, the bacterial burdens in harvested lung tissues were estimated. As shown in Table 1, the numbers of CFU in the PAO1 and PAO1 + S.mitis groups were significantly higher than that in the PBS control group (p = 0.01 and p = 0.01, respectively). More interestingly, although more bacteria were injected initially in the PAO1 + S. mitis group, after 48 h, the numbers of CFU did not differ significantly between the PAO1 and PAO1 + S. mitis groups (p > 0.05). Additionally, the number of CFU in the S. mitis group did not differ from that in the PBS control group (p > 0.05).

Histological observation of lung tissues from acute lung infection mouse models

Wild-type mice had severe lung damage after P. aeruginosa challenge (Fig. 1b). Numerous foci of necrosis and inflammatory infiltrates were discovered, with increased numbers of alveolar macrophages infiltrating the alveolar septa, as compared with the PBS group. However, little change was observed upon infection of wild-type mice with S. mitis, with almost no macrophage infiltration in the lungs (Fig. 1c). Notably, in the PAO1 + S. mitis group, moderate lung inflammation was observed, with recruitment of inflammatory cells in the peribronchial wall and surrounding the vessels (Fig. 1d). Similar to wild-type mice, TLR4-deficient mice infected with S. mitis, PAO1 + S. mitis, or PAO1 showed slight, moderate, and severe lung inflammation, respectively (Fig. 2).

HE-stained lung tissues from wild-type acute lung infection mouse models. After the wild-type mice were infected with PAO1 (b), S. mitis (c), PAO1 + S. mitis (d), or PBS (a) for 48 h, mice were sacrificed and right lungs were stained with HE to observe histological changes. Original magnification, ×200

HE-stained lung tissues from TLR4-deficient acute lung infection mouse models. After the TLR4-deficient mice were infected with PAO1 (b), S. mitis (c), PAO1 + S. mitis (d), or PBS (a) for 48 h, mice were sacrificed and right lungs were stained with HE to observe histological changes. Original magnification, ×100

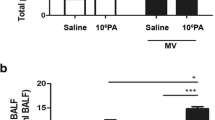

Cell counts in BALF

Among infected wild-type mice, the S. mitis group showed little change in the total cell count in BALF, as compared to the PBS group (2.17 ± 1.90(×106) vs 3.2 ± 1.9(×105), p > 0.05). However, the total cell counts were slightly increased in the PAO1 and PAO1 + S. mitis groups (Fig. 3a). Similar results were obtained in TLR4-deficient mice (Fig. 3b). Interestingly, TLR4-deficient mice infected with PAO1 + S. mitis had significantly lower total cell counts in BALF compared with TLR4-deficient mice infected with PAO1 only (p < 0.001), which is consistent with the results of histological examination of lung tissues. In comparing wild-type and TLR4-deficient mice (Fig. 3c), we found that the BALF of TLR4-deficient mice showed significantly lower total cell counts in each comparative group (all p < 0.05).

IL-6 and TNF-α protein expression

TLR4 recognizes specific bacterial molecules, and their binding initiates host immune responses such as expression of proinflammatory cytokines TNF-α and IL-6. To better understand the immune response in our mouse models, the concentrations of TNF-α and IL-6 were measured. Significantly increased protein levels of IL-6 and TNF-α (p < 0.001 and p < 0.001, respectively) were observed in wild-type mice challenged with PAO1 compared with levels in the PBS group (Fig. 4). By contrast, S. mitis infection hardly induced the secretion of these two cytokines (p > 0.05). While increased IL-6 and TNF-α expression was observed the PAO1 + S. mitis group relative to the PBS group, these cytokine levels were still lower than those in the PAO1 group (p = 0.001 and p = 0.002, respectively). Interestingly, after infection of TLR4-deficient with the different bacteria (Fig. 4), expression of both IL-6 and TNF-α was almost completely inhibited, with no statistically significant differences in expression levels among the four treatment groups (p > 0.05). In comparison to IL-6 and TNF-α expression levels in wild-type mice, the concentrations of IL-6 and TNF-α were lower in TLR4-deficient mice infected with PAO1 with or without S. mitis (p < 0.001 and p = 0.005, respectively; Fig. 4).

IL-6 and TNF-α concentrations in BALF. The IL-6 protein levels in BALF of wild-type mice and TLR4-deficient mice and the differences in IL-6 protein levels between wild-type and TLR4-deficient mice (a) are shown. The TNF-α protein levels in BALF of wild-type mice and TLR4-deficient mice and the differences between in TNF-α protein levels wild-type and TLR4-deficient mice (b) are shown

Discussion

As is known, VAP is a principal cause of morbidity, mortality, and economic burden in ICUs. Increasing antimicrobial resistance has drawn attention to the failure of antibiotic treatment. Recent progress has mainly focused on the pathogenicity and antimicrobial resistance of a single strain, specifically P. aeruginosa, on the ETTs. However, few studies have investigated the interaction of multiple bacteria in the pathogenesis of VAP. Based on our previous research, we further investigated the presence of S. mitis and P. aeruginosa on the ETTs. Here, for the first time to our knowledge, we found that S. mitis can counteract the inflammatory potential of P. aeruginosa possibly through TLR4 signaling in acute lung infection.

S. mitis is the most abundant bacteria of the normal human oral flora and also a predominant colonizer of the mucosal site, usually inhabiting the human oral cavity as early as 1–3 days after birth. Moreover, except for endocarditis [18], S. mitis rarely causes diseases. In our previous research, we found that wild-type mice as well as TLR4-deficient mice infected with an S. mitis strain for 48 h showed little change in pulmonary lesions, supporting the common notion that S. mitis is a normal commensal bacteria in the human oropharynx [19–21].

In the present study, we observed more severe inflammation in lung tissues accompanied with infiltration of more inflammatory cells in the PAO1 + S. mitis group compared with the S. mitis group and PBS control group, but less severe lung inflammation in comparison with that in the PAO1 group. These findings suggest that in acute lung infection, S. mitis helps to alleviate the inflammatory response so as to reduce the local tissue damage. Several studies have found similar effects, in which the bacteria mainly act as “protectors” during the process of infection. Recent findings in Bifidobacteria and Lactobacilli have confirmed that they are effective at reducing allergic symptoms and inhibiting the allergic airway response in murine models of acute airway inflammation [22, 23]. More important, this inhibition is possibly achieved by regulating TLR signaling [24]. Therefore, we have reason to believe that, unlike the traditional concept in which S. mitis is considered normal commensal bacteria, our results indicate that S. mitis might play a potential protective role in the respiratory tract during acute lung infection. Also considering our results in TLR4-deficient mice, we conclude that S. mitis may help alleviate lung inflammation, possibly through modulation of TLR pathway signaling.

Additionally, the total cell counts in BALF are important indicators of the proliferation and differentiation of inflammatory cells. After infection of wild-type mice, total cell counts in the S. mitis group were hardly increased, whereas those in the PAO1 group were significantly increased compared with the PBS group. These findings are consistent with the results of lung histopathological examination. However, the total cell counts in the PAO1+ S. mitis group were slightly lower than those in the PAO1 group. We speculate that S. mitis might activate some other signaling pathways in the process of promoting inflammatory cells. Some studies have found that S. mitis reduces proliferation of T cells specific to an unrelated antigen (TT), which suggests an inhibitory effect of S. mitis. This inhibition can affect either the antigen-presenting cells (APCs) directly by preventing activation and/or antigen presentation or on the memory Th cells directly by interfering with the APC–T cell interaction [5]. We speculate that this might be one possible explanation for our observations. After infection of TLR4-deficient mice, the total cell counts were significantly lower than those in wild-type mice, which indicates that TLR4 expressed on cell surface is needed for inflammatory cell activation [25].

Several studies have demonstrated that TNF-α activates the expression of endothelial adhesion molecules to facilitate migration of neutrophils into inflamed lungs [26]. Similarly, in our acute lung infection mouse models, we found that wild-type mice infected with PAO1 showed significantly increased TNF-α protein expression as well as increased IL-6 expression. These findings are consistent with the literature, which supportes that IL-6 modulates almost every aspect of the innate immune system, including the accumulation of neutrophils at sites of infection or trauma through the control of granulopoiesis [27, 28]. Previous studies have confirmed that TLR4 plays a crucial role in the recognition of Gram-negative bacteria, but has no obvious effects on Gram-positive bacteria [25, 29]. However, our present study showed that P. aeruginosa together with S. mitis could affect activity of the TLR4 pathway. Although we examined the TLR4 pathway specifically, the roles of other TLR pathways cannot be excluded and should be considered in future investigations.

In contrast with our study, Wang et al. found an opposite result, which confirmed that S. mitis mainly secrets autoinducer-2 to promote biofilm formation and to increase proinflammatory cytokine production, resulting in severe inflammation [6]. This difference might be attributed to the different infection models. In their study, chronic pneumonia rat models were established by dual-biofilm catheter intubation for 7 days. In contrast, in our study, acute lung infection mouse models were established by planktonic bacteria infection for only 48 h. However, further investigations are needed to elaborate the mechanisms. Additionally, we speculate that the conflicting results are related to the protective effects of S. mitis in acute infection, which resulted in reduced cytokine secretion by the host immune system and weakened bacterial clearance, finally resulting in persistent and chronic infection.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the results of this study will contribute to a better understanding of the co-existence of P. aeruginosa and S. mitis, and for the first time, we demonstrate that S. mitis plays a potentially protective role in the respiratory tract during acute infection. These findings may provide a new perspective in the treatment of P. aeruginosa infection in the NICU. The mechanisms underlying the protective effect of S. mitis remain unknown, and further studies are needed to discover whether this effect is mediated by TLR signaling directly or via some small molecules or whether S. mitis simply competes with PAO1 for nutrients, limiting PAO1 replication.

Abbreviations

- BALF:

-

Bronchoalveolar lavage fluid

- CFU:

-

Colony-forming units

- ETTs:

-

Endotracheal tubes

- H&E:

-

Hematoxylin-eosin

- LPS:

-

Lipopolysaccharide

- P. aeruginosa :

-

Pseudomonas aeruginosa

- PAMPs:

-

Pathogen-associated molecular patterns

- PBS:

-

Phosphate-buffered saline

- S. mitis :

-

Streptococcus mitis

- TLR:

-

Toll-like receptor

- TT:

-

Unrelated antigen

- VAP:

-

Ventilator-associated pneumonia

References

Ismail A, El-Hage-Sleiman AK, Majdalani M, Hanna-Wakim R, Kanj S, Sharara-Chami R. Device-associated infections in the pediatric intensive care unit at the American University of Beirut Medical Center. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2016;10(6):554–62.

Hocevar SN, Edwards JR, Horan TC, Morrell GC, Iwamoto M, Lessa FC. Device-associated infections among neonatal intensive care unit patients: incidence and associated pathogens reported to the National Healthcare Safety Network, 2006-2008. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2012;33(12):1200–6.

Hongdong Li CS, Liu D, Ai Q, Yu J. Molecular analysis of biofilms on the surface of neonatal endotracheal tubes based on 16S rRNA PCR-DGGE and species-specific PCR. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2015;8(7):11075–84.

YJ SC, Ai Q, Liu D, Lu W, Lu Q, Peng NN. Diversity analysis of biofilm bacteria on tracheal tubes removed from intubated neonates. Zhonghua Er Ke Za Zhi. 2013;51(8):602–6.

Khosravi Y, Dieye Y, Loke MF, Goh KL, Vadivelu J. Streptococcus Mitis induces conversion of helicobacter pylori to coccoid cells during co-culture in vitro. PLoS One. 2014;9(11):e112214.

Wang Z, Xiang Q, Yang T, Li L, Yang J, Li H, He Y, Zhang Y, Lu Q, Yu J. Autoinducer-2 of Streptococcus Mitis as a target molecule to inhibit pathogenic multi-species Biofilm formation in vitro and in an Endotracheal intubation rat model. Front Microbiol. 2016;7(88):1–11.

Knapp S. Update on the role of Toll-like receptors during bacterial infections and sepsis. Wien Med Wochenschr. 2010;160(5–6):107–11.

Wieland CW, van Lieshout MH, Hoogendijk AJ, van der Poll T. Host defence during Klebsiella pneumonia relies on haematopoietic-expressed Toll-like receptors 4 and 2. Eur Respir J. 2011;37(4):848–57.

Frazao JB, Errante PR, Condino-Neto A. Toll-like receptors’ pathway disturbances are associated with increased susceptibility to infections in humans. Arch Immunol Ther Exp. 2013;61(6):427–43.

Brown J, Wang H, Hajishengallis GN, Martin M. TLR-signaling networks: an integration of adaptor molecules, kinases, and cross-talk. J Dent Res. 2011;90(4):417–27.

Greenhill CJ, Rose-John S, Lissilaa R, Ferlin W, Ernst M, Hertzog PJ, Mansell A, Jenkins BJ. IL-6 trans-signaling modulates TLR4-dependent inflammatory responses via STAT3. J Immunol. 2011;186(2):1199–208.

Liu Y, Yin H, Zhao M, Lu Q. TLR2 and TLR4 in autoimmune diseases: a comprehensive review. Clinical reviews in allergy & immunology. 2014;47(2):136–47.

Perros F, Lambrecht BN, Hammad H. TLR4 signalling in pulmonary stromal cells is critical for inflammation and immunity in the airways. Respir Res. 2011;12:125.

Schoeniger A, Fuhrmann H, Schumann J. LPS- or Pseudomonas Aeruginosa-mediated activation of the macrophage TLR4 signaling cascade depends on membrane lipid composition. PeerJ. 2016;4:e1663.

Fremond CM, Nicolle DM, Torres DS, Quesniaux VF. Control of Mycobacterium Bovis BCG infection with increased inflammation in TLR4-deficient mice. Microbes Infect. 2003;5(12):1070–81.

Caron E, Desseyn JL, Sergent L, Bartke N, Husson MO, Duhamel A, Gottrand F. Impact of fish oils on the outcomes of a mouse model of acute Pseudomonas Aeruginosa pulmonary infection. Br J Nutr. 2015;113(2):191–9.

Ding FM, Zhu SL, Shen C, Ji XL, Zhou X. Regulatory T cell activity is partly inhibited in a mouse model of chronic Pseudomonas Aeruginosa lung infection. Exp Lung Res. 2015;41(1):44–55.

Khan ST, Ahmad J, Ahamed M, Musarrat J, Al-Khedhairy AA. Zinc oxide and titanium dioxide nanoparticles induce oxidative stress, inhibit growth, and attenuate biofilm formation activity of Streptococcus Mitis. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2016;21(3):295–303.

Mitchell J. Streptococcus Mitis: walking the line between commensalism and pathogenesis. Mol Oral Microbiol. 2011;26(2):89–98.

Jennifer L, Kirchherra GHB, Michael F. Colea, Yoshiaki Kawamurac, Dorothy, A. Richmondd MJS, and Katherine a. Wirth: physiological and serological variation in S. mitis biovar 1 from the human oral cavity during the first year of life. Arch Oral Biol. 2007;52(1):90–9.

Mager DL, Ximenez-Fyvie LA, Haffajee AD, Socransky SS. Distribution of selected bacterial species on intraoral surfaces. J Clin Periodontol. 2003;30(7):644–54.

Sagar S, Morgan M, Chen S, Vos AP, Garssen J, van Bergenhenegouwen J, Boon L, Georgiou NA, Kraneveld AD, Folkerts G. Bifidobacterium breve and lactobacillus rhamnosus treatment is as effective as budesonide at reducing inflammation in a murine model for chronic asthma. Respir Res. 2014;16(15):1–17.

Hougee S, Vriesema AJ, Wijering SC, Knippels LM, Folkerts G, Nijkamp FP, Knol J, Garssen J. Oral treatment with probiotics reduces allergic symptoms in ovalbumin-sensitized mice: a bacterial strain comparative study. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2010;151(2):107–17.

Kalliomaki M, Antoine JM, Herz U, Rijkers GT, Wells JM, Mercenier A. Guidance for substantiating the evidence for beneficial effects of probiotics: prevention and management of allergic diseases by probiotics. J Nutr. 2010;140(3):713S–21S.

van Helden SF, van den Dries K, Oud MM, Raymakers RA, Netea MG, van Leeuwen FN, Figdor CG. TLR4-mediated podosome loss discriminates gram-negative from gram-positive bacteria in their capacity to induce dendritic cell migration and maturation. J Immunol. 2010;184(3):1280–91.

Pandit AA, Choudhary S, Ramnee K, Singh B, Sethi RS. Imidacloprid induced histomorphological changes and expression of TLR-4 and TNFalpha in lung. Pestic Biochem Physiol. 2016;131:9–17.

Hunter CA, Jones SA. IL-6 as a keystone cytokine in health and disease. Nat Immunol. 2015;16(5):448–57.

Tanaka T, Narazaki M, Kishimoto T. IL-6 in inflammation, immunity, and disease. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2014;6(10):1–17.

Neyen C, Lemaitre B. Sensing gram-negative bacteria: a phylogenetic perspective. Curr Opin Immunol. 2016;38:8–17.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Professor Yibing Yin (Key Laboratory of Diagnostic Medicine Designated by the Ministry of Education, Chongqing Medical University, Chongqing, China) for excellent technical support.

Funding

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 81,370,744, 81,571,483), which provided money to buy reagents. Doctoral Degree Funding from the Chinese Ministry of Education (No. 20135503110009), and the State Key Clinic Discipline Project (No. 2011–873), which provided money for the labor costs, and the Clinical Research Foundation of Children’s Hospital of Chongqing Medical University, which provide the money for article modification.

Availability of data and materials

The data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article. Additional data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Authors’ contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: CS, JY. Performed the experiments: CS, HL, YZ. Analyzed the data: CS, YZ. Wrote the paper: CS. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ information

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The experimental protocol was approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Chongqing Medical University.

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and Institutional affiliations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Song, C., Li, H., Zhang, Y. et al. Effects of Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Streptococcus mitis mixed infection on TLR4-mediated immune response in acute pneumonia mouse model. BMC Microbiol 17, 82 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12866-017-0999-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12866-017-0999-1