Abstract

Background

The aim of this study was to evaluate the effects of β-glucan on the expression of inflammatory mediators and metabolomic profile of oral cells [keratinocytes (OBA-9) and fibroblasts (HGF-1) in a dual-chamber model] infected by Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans. The periodontopathogen was applied and allowed to cross the top layer of cells (OBA-9) to reach the bottom layer of cells (HGF-1) and induce the synthesis of immune factors and cytokines in the host cells. β-glucan (10 μg/mL or 20 μg/mL) were added, and the transcriptional factors and metabolites produced were quantified in the remaining cell layers and supernatant.

Results

The relative expression of interleukin (IL)-1-α and IL-18 genes in HGF-1 decreased with 10 μg/mL or 20 μg/mL of β-glucan, where as the expression of PTGS-2 decreased only with 10 μg/mL. The expression of IL-1-α increased with 20 μg/mL and that of IL-18 increased with 10 μg/mL in OBA-9; the expression of BCL 2, EP 300, and PTGS-2 decreased with the higher dose of β-glucan. The production of the metabolite 4-aminobutyric acid presented lower concentrations under 20 μg/mL, whereas the concentrations of 2-deoxytetronic acid NIST and oxalic acid decreased at both concentrations used. Acetophenone, benzoic acid, and pinitol presented reduced concentrations only when treated with 10 μg/mL of β-glucan.

Conclusions

Treatment with β-glucans positively modulated the immune response and production of metabolites.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

β-glucans from yeast have been used extensively as protective substances against infections with potent effects on the innate and adaptive immune responses. β-glucans are non-starch polysaccharides that make up structural cells of plants and microorganisms [1]. The cell wall of Saccharomyces cerevisiae is an important source of β-glucans and these represents about 50–60% of yeast [2]. The protective effect of these compounds has been demonstrated in experimental infection [3]. Additionally, there are reports that these substances modulate allergy symptoms [4] and have anticancer properties [5, 6]. Many hypotheses have been put forward to explain the effects of β-glucans. Such compounds can act by inhibiting the adhesion of pathogens to epithelial tissues of the digestive tract by blocking carbohydrate-binding adhesins on bacteria; they stimulate the immunocompetent cells in Peyer’s patches and the consecutive activation of mechanisms of innate and adaptive immune defense; further, by adsorption of mycotoxins in food (when linked to the diet) β-glucans inhibit their toxic activity [2].

However, its effects on periodontal inflammation are still poorly studied. Periodontal disease is a highly prevalent disease in the adult population. It is characterized by inflammation and progressive destruction of the periodontal tissues in response to specific microorganisms present in oral biofilm [7,8,9,10]. The pathogens associated with periodontal disease are frequently present in the human subgingival microbiota and are represented mainly by anaerobic gram-negative bacteria [11]. A. actinomycetemcomitans, Pasteurellaceae family, is a coccobacillus, fermentative, gram-negative, capnophilic, non-motile, and non-sporulating microorganism. This bacterium is considered the main etiological agent of localized aggressive periodontitis lesions, but is also associated with chronic periodontitis [12,13,14,15,16,17,18]. The progression of periodontal disease is associated with the virulence of the microorganism, together with the susceptibility of the host [19]. There are several virulence factors of A. actinomycetemcomitans that collaborate for its pathogenicity in periodontitis [20]. Leukotoxin, cytolethal distending toxins, bacteriocins, adhesins and lipopolysaccharide correspond to the variety of the microorganism virulence factors that may be associated with the pathogenesis of localized aggressive periodontitis [21]. These virulence factors attributed to A. actinomycetemcomitans are responsible for interacting with the host cells triggering an inflammatory response in the tissues supporting the teeth [22].

Fibroblasts and epithelial cells are the first cells to be activated in the oral cavity in response to exotoxic and endotoxic virulence factors of A. actinomycetemcomitans, performing an essential role in the production of cytokines involved in the inflammatory process. After this first local colonization, leukocytes (mainly monocytes and neutrophils) and dendritic cells are recruited to the site of infection giving sequence on inflammatory response [22, 23].

Recently, in vivo studies have demonstrated that β-glucans from S. cerevisiae present regulatory activity toward metabolism [24] and also modulate the expression of cycloxygenase-2 (COX-2), receptor activator of nuclear factor kappa-B ligand (RANK-L), and osteoprotegerin (OPG), decreasing alveolar bone loss caused by induced periodontal disease (ligature) in normal and diabetic animals [25]. However, knowledge of the molecular and biochemical mechanisms involved in β-glucan activity in periodontal disease is still not understood, demanding further research with advanced tissue culture techniques, examining the microbiota-host interaction. In that sense, the dual chamber model is an interesting in vitro model that mimics the human periodontum. It is constructed using a monolayer of epithelial keratinocytes and a subepithelial layer of fibroblasts on which the invasive periodontopathogen can be applied [26].

Thus, this study aims to evaluate the effects of β-glucan on the expression of inflammatory mediators and the metabolomic profile of oral cells using a dual-chamber model of epithelial and subepithelial cells infected by A. actinomycetemcomitans.

Methods

Bacterial strain and cells

A. actinomycetemcomitans strain (D7S-1) [27], human gingival epithelial cells (keratinocyte OBA-9) [28, 29] and human gingival fibroblast - HGF-1(ATCC® CRL-2014) were used in the present study.

β-Glucan

The β-glucan utilized was the glucan from baker’s yeast S. cerevisiae (Sigma-Aldrich; St. Louis, MO), with a purity of 98%. Sterilized deionized water was used as the vehicle for β-glucan dilution.

Antimicrobial activity

As a preliminary step, the antimicrobial activity and cytotoxicity of β-glucan were tested in order to determine the subsequent doses in the dual-chamber model. Antimicrobial activity was evaluated in A. actinomicetemcomitans after 24 h of treatment. Microorganisms were inoculated (1 × 106 cfu/mL – colony-forming units per milliliter) in a 96-well microtiter plate with Trypticase Soy Broth (TSB; Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ) and β-glucan was immediately added in various concentrations (0 as control, and then subsequently from 1 μg/mL to 100 μg/mL) to determine the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) [30]. Microplates were maintained in a humidified incubator at 37 °C and 5% CO2. Microplates were maintained in a humidified incubator at 37 °C and 5% CO2. After 24 h, the contents of the wells were inoculated in Petri dishes with Trypticase Soy Agar (TSA; Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ) and incubated for 3 days. After this period, the cfu/mL was determined.

Cytotoxicity assay

The in vitro cytotoxic effect was measured by the fluorometric resazurin method [31]. OBA-9 or HGF-1cells, cultured in DMEN medium (Lonza,Walkersville, MD) with10% of Fetal Bovine Serum - FBS (Lonza, Walkersville, MD), were seeded (1 × 105 cells/mL) in a 96-well microtiter plate and maintained in a humidified incubator at 37 °C and 5% CO2. After 24 h, cell morphology was observed under an inverted microscope (EVOS FL; Life Technologies, Carlbad, CA) to confirm their adherence to the wells and to note their morphological changes. β-glucan (1–100 μg/mL) was added to the cell culture and incubated at 37 °C and 5% CO2. After 24 h, the medium was discarded, cells were washed with warm PBS (Lonza, Walkersville, MD), and replenished with fresh medium containing resazurin (Cell Titer Blue Viability Assay; Promega Corp, Madison, WI) [32]. Subsequently the plate was incubated at 37 °C and 5% CO2. After 4 h, the contents of the wells were transferred to a new microplate and the fluorescence was read in a microplate reader (SpectraMaxM5; Molecular Devices Sunnyvale, CA) with excitation at 550 nm, emission at 585 nm, and a cut off of 570 nm.

Dual-chamber assay

The immunological effects of β-glucan were investigated using a dual-chamber model to mimic the periodontum (Fig. 1). Transwell inserts (8 μm pore × 0.3 cm2 of culture surface; Greiner Bio-One, Monroe, NC) were situated in a 24-well plate and OBA-9 cells (1 × 105) were seeded intranswell inserts. HGF-1cells (1 × 105) were seeded in the basal chamber. The plates were incubated at 37 °C in humid air containing 5% CO2 for 24 h. The trans-epithelial electric resistance (TEER) of each cell layer was measured with a Millicell-ERS volt-ohm meter (Millipore, Bedford, MA). Cell layer confluence in the Transwell insert was measured daily until optimal TEER was reached (>150 Ohm/cm2) which was found on the second day, when the medium in the basal chamber and insert were replaced with new medium (DMEN) containing A. actinomicetemcomitans (1 × 106 cfu/mL). Medium containing the microorganism was added to the insert, passing through the upper layer of cells (OBA-9) and reaching the bottom cell layer (HGF-1) [26]. Immediately after inoculation of the dual-chamber with A. actinomicetemcomitans the β-glucan treatments (10 μg/mL or 20 μg/mL) were added and the plate was incubated at 37 °C in humid air containing 5% CO2. The time of exposure of the microorganism to β-glucan was 24 h. Each experiment was repeated three times with two replicates per group (n = 6) and the experimental groups were divided as described in Table 1. The two doses used were determined from the results found in the antimicrobial activity and cytotoxicity assay.

Sample collection for analysis

After the treatment period, the liquid contents of the wells were collected and centrifuged at 1200 rpm for 10 min. Following centrifugation, the supernatant was stored at −80 °C for subsequent metabolomic analysis. The remaining cell layer on the surface of the inserts and of the plate wells were used for RNA isolation (OBA-9 and HGF-1 separately) for gene analysis in quantitative real-timePCR.

Gene expression –quantitative real-time PCR

Total RNA was isolated according to the Qiagen RNeasyMini Kit Protocol (Qiagen; Valencia CA). Purity and quantity of RNA were measured in a NanoPhotometer P360 (Implen; Westlake Village). Total RNA was converted into single-stranded cDNA using a high-capacity reverse transcription kit (QuantiTect Reverse Transcription Kit; Qiagen; Valencia, CA). From the cDNA obtained, an array for evaluation of gene expression of inflammatory response by quantitative real-time PCR (Prime PCR Pathway Plate/Acute Inflammation Response; Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA), was performed. Based on the results of the array, five genes/primers were selected for detailed study: IL-1-α, IL-18, B-cell lymphoma-2 (BCL-2), E1A Binding Protein (EP300) and prostaglandin-endoperoxidesynthase-2 (PTGS-2) (QuantiTect Primer Assay - Qiagen; Valencia, CA). For the selected primers, QuantiTect SYBR Green PCR Kits (Qiagen;Valencia, CA) were used. The reaction product was quantified by relative quantification using GAPDH as a reference gene. Data from standard threshold cycle (TC) of the equipment in real time (CFX Connect-Bio-Rad; Hercules, CA) were calculated and interpreted using the scan tool data qPCR array. Analysis of the relative quantitation was done using the ΔΔCt comparative method [33].

Metabolome analysis

The cell culture supernatant contents of the wells were collected and centrifuged at 1200 rpm for 10 min, at room temperature. Then, the supernatant was properly stored and sent for analysis at West Coast Metabolomics Center (UC Davis Genome Center; Davis, CA) for subsequent metabolomic analysis.

The metabolites were separated by gas chromatography/mass spectrometry (Agilent 6890, Santa Clara, CA/Leco Pegasus IV, St. Joseph, MI) according to standard methodology. The metabolites found were submitted to a comparison software and compared with a standard library of metabolites. Subsequently the data were submitted to statistical analysis (West Coast Metabolomics Centre (UC Davis Genome Center; Davis, CA) [34].

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were done using analysis of variance (ANOVA). When F values indicated significant interactions, these were unfolded between factors. The analyses were performed in the statistical program SISVAR [35] at a significance level of α = 0.05.

Results

The antibacterial activity of β-glucan started at 10 μg/mL. Cytotoxicity assays were conducted in HGF-1 and OBA-9 cells and the results are shown in Fig. 2. The first concentration used was 10 μg/mL of β-glucan and resulted in 125% viability for HGF-1 and 104% for OBA-9 cells (Fig. 2a). The second concentration used was 20 μg/mL of β-glucan and resulted in 100% viability for HGF-1 and 90% for OBA-9 cells (Fig. 2b).

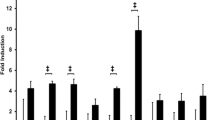

Quantitative real-time PCR results are presented in Figs. 3 and 4. Based on gene expression results of the inflammatory profile (acute inflammation response), five genes that showed greater variation in their expression (up or down regulation) were selected for detailed analysis: IL-1-α, IL-18, BCL-2, EP-300, and PTGS-2. The relative expression of IL-1-α (Fig. 3a) and IL-18 (Fig. 3b) genes in HGF-1 decreased with 10 μg/mL or 20 μg/mL of β-glucan in comparison with the control group (p < 0.05). In the same way, the expression of PTGS-2 (Fig. 3e) decreased with 10 μg/mL treatment; however, at a dose of 20 μg/mL it remained equal to that of the control group (p < 0.05). The expression of the BCL-2 (Fig. 3c) and EP-300 (Fig. 3d) genes were similar among groups.

Relative expression of genes on HGF-1 cells (fibroblasts) by quantitative PCR: (a) interleukin 1 alpha (IL-1-α); (b) interleukin 18 (IL-18); (c) B-cell lymphoma 2 (BCL-2); (d) adenovirus E1A-associated 300 kDa protein (EP 300); (e) prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 2 (PTGS-2). Dual-chamber model inoculated with A. actinomicetemcomitans and treated with different doses of β-glucan. The control group has their mean expressed equal to 1 and treated groups have their mean relative to the control group. The results were expressed by mean followed standard deviation; n = 6 and P < 0.05

Relative expression of genes on OBA-9 cells (keratinocytes) by quantitative PCR: (a) interleukin 1 alpha (IL-1-α); (b) interleukin 18 (IL-18); (c) B-cell lymphoma 2 (BCL-2); (d) adenovirus E1A-associated 300 kDa protein (EP 300); (e) prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 2 (PTGS-2). Dual-chamber model inoculated with A. actinomicetemcomitans and treated with different doses of β-glucan. The control group has their mean expressed equal to 1 and treated groups have their mean relative to the control group. The results were expressed by mean followed standard deviation; n = 6 and P < 0.05

For OBA-9, the expression of the IL-1-α (Fig. 4a) gene increased with 20 μg/mL and IL-18 (Fig. 4b) expression increased with 10 μg/mL (p < 0.05). The expression of BCL-2 (Fig. 4c), EP 300 (Fig. 4d), and PTGS-2 (Fig. 4e) decreased with the higher dose of β-glucan (p < 0.05).

The metabolomic study yielded a total of 283 metabolites, of which 120 were identified. Some metabolites presented significantly altered concentrations (Fig. 5). The 20 μg/mL β-glucan treatment presented lower (p < 0.05) concentrations of 4-aminobutyric acid (Fig. 5a). It was also observed that the β-glucan treatments used decreased (p < 0.05) the concentrations of 2-deoxytetronic acid NIST (Fig. 5b) and oxalic acid (Fig. 5e) at both concentration used (10 μg/mL and 20 μg/mL). Acetophenone NIST (Fig. 5c), benzoic acid (Fig. 5d) and pinitol (Fig. 5f) presented reduced (p < 0.05) concentrations when treated with only 10 μg/mL of β-glucan. All treatments were compared with the control group.

Metabolites obtained of cell culture supernatant (HGF-1 and OBA-9 co-culture cells). (a) 4-aminobutyric acid; (b) 2-deoxytetronic acid NIST; (c) acetophenone NIST; (d) benzoic acid; (e) oxalic acid; (f) pinitol. Dual-chamber model inoculated with A. actinomicetemcomitans and treated with different doses of β-glucan. The data is expressed in relative peak heights (mAU) from HPLC-MS analysis, which are unit-less (mean followed standard deviation); n = 4 and P < 0.05

Discussion

Human gingival fibroblasts represent the main cell type that form the soft connective tissues of the periodontium. These cells have a direct interaction with bacteria and their products [36], and perform an essential role in the production of cytokines involved during the inflammatory process [23]. The β-glucans present a capacity to stimulate the production of proinflammatory cytokines, thus modulating immune responses both specific and non-specific. Here, the authors extend further on their previous in vivo discovery [25] by showing the effects of β-glucans on gene expression of inflammatory cytokines and the metabolomic profile of mammalian cells.

For this study, the toxicity, anti-inflammatory activity, and effects on the transcriptome/metabolome of β-glucans on human cells were evaluated. The gene expression of IL-1-α and IL-18 in fibroblasts was reduced in the models treated with β-glucans. IL-1 is considered as a marker of periodontitis due to their involvement in the inflammation process (as inflammatory mediator) and its participation in the extracellular matrix and bone metabolism [37, 38]. In a study of experimental gingivitis, an increased concentration of IL-1 in gingival crevicular fluid was demonstrated [39]. The expression of IL-1-α and IL-1-β was induced in vitro from cultured gingival epithelial cells that were challenged with A. actinomicetemcomitans extracts [40]. These results indicate that gingival epithelial cells are the main source of these interleukins of the periodontium, which induce the production of additional inflammatory mediators [40]. IL-18 has pleiotropic action and participates in the innate and acquired immune responses [41], indicating a positive effect of β-glucan in reducing the expression of both IL-1-α and IL-18 in human fibroblasts. The decrease in these parameters may suggest an improvement in the inflammatory response associated with the immunomodulatory effects of β-glucans associated with their antimicrobial activity [3,43,, 42–44]. Antagonistically, the expression of these same cytokines (IL-1-α and IL-18) observed in keratinocytes (OBA-9), indicated a result contrary to that seen in fibroblasts (HGF-1). Treatment with β-glucan increased the expression of IL-1-α and IL-18. This response may be due to a compensatory interaction between these different cell types. According to Di et al. [45], the expression of KGF (keratinocyte growth factor) and KGFR (keratinocyte growth factor receptor) observed in cocultures of keratinocytes and fibroblasts was influenced by the interaction of these different gingival cells. According to these authors, keratinocytes and fibroblasts can interact to dynamically regulate gene expression, what could have had such an effect on gingival cells conditions after treatment. In addition, the use of β-glucan decreased BCL-2 expression in keratinocytes. This protein exerts an antiapoptotic function, performing an essential role in the development of the immune response and tissue homeostasis [46].

β-glucan therapy regulated the expression of other immunomodulatory genes (EP300 and PTGS2), which shows an effect on more than one signaling pathway and can result in an important therapeutic effect. EP300, also known as p300, is involved in cell growth, proliferation, apoptosis, and embryogenesis [47, 48]. Some changes in its structure (derived from mutations) and the altered activity of this protein are linked with inflammation, malignant tumors, and developmental abnormalities [48]. Deng et al. [49] observed that p300 is involved in the stimulation of COX-2 expression induced by proinflammatory mediators. In the current study, treatment with β-glucan reduced EP300 expression in keratinocytes.

PTGS2, also known as COX-2, is an enzyme that is involved in the conversion of arachidonic acid to prostaglandins, performing an important role in the inflammatory response of periodontal tissues [50]. This enzyme has a preferentially inducible profile and is expressed by cells related to inflammatory processes [51] such as the response to inoculation by pathogenic micro-organisms. A recent study performed by our research group demonstrated lower COX-2 expression in diabetic rats with induced periodontal disease that were treated with β-glucan from S. cerevisiae [25]. Similarly, the present study showed a reduction in PTGS-2 expression, suggesting an improvement in the inflammatory profile as a function of treatment with β-glucan.

The metabolomic study in the present work explored the influence of β-glucan treatment on cell metabolic profile and found significant changes in 4-aminobutyric acid, 2-deoxytetronic acid NIST, oxalic acid, acetophenone NIST, benzoic acid, and pinitol. 4-aminobutyric acid, more commonly known as gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), is a non-protein amino acid that acts as the main inhibitory neurotransmitter of the central nervous system in animals and humans [52]. Some studies have linked increased intake of GABA or its analogs with multiple health benefits, for example, lowering blood pressure in hypertensive animals and humans [53,54,55,56]. In addition, studies indicate that GABA ingestion from enriched natural sources, has an inhibitory effect on the proliferation of cancer cells and has a enhancer action on cancer cell apoptosis [57]. Other compounds, such as benzoic acid and pinitol, are derived from plants and have multifunctional properties. Benzoic acid is an aromatic carboxylic acid present in the tissues of plants and animals and can also be produced by microorganisms [58]. Pinitol, also called D-pinitol, is a compound with multifunctional properties, among them, anti-inflammatory, cardioprotective, and anti-hyperlipidemicactions. Furthermore, pinitol is known to have properties similar to those of insulin [59,60,61].

A study compared the metabolomic profile of patients with different levels of gingival bleeding. Metabolomic analysis of this study indicated significant changes in the composition of metabolites, especially the short chain carboxylic acids propionate and n-butyrate, which tracked clinical changes in gingivitis severity [62]. Another study analyzed the metabolomic profile in saliva and plasma samples of diabetic patients with healthy periodontium, gingivitis and periodontitis. They observed increased levels of markers of cellular energetic stress, increased purine degradation and glutathione metabolism through increased levels of oxidized glutathione and cysteine-glutathione disulfide, markers of oxidative stress (guanosine and inosine), increased amino acid levels suggesting protein degradation, and increased ω-3 (docosapentaenoate) and ω-6 fatty acid (linoleate and arachidonate). According to the authors, these metabolites associated with the periodontal condition may be useful for developing diagnoses and therapeutics adapted to the diabetic population [63]. Thus, we believe that metabolomic profile analysis may be a useful tool in investigating of the β-glucans action on periodontal disease and the changes in metabolites can be used as markers of the disease.

The results observed in the present study demonstrated that the β-glucan was able to modulate gene expression and alter the concentrations of different metabolites by modifying the immune cell response to a challenge with A. actinomicetemcomitans. β-glucan treatment (10 μg/mL or 20 μg/mL) reduced the concentrations of 4-aminobutyric acid, 2-deoxytetronic acid NIST, oxalic acid, acetophenone NIST, benzoic acid, and pinitol. In fibroblasts (HGF-1), the relative expression of IL-1-α, IL-18, and PTGS-2 genes decreased with 10 μg/mL or 20 μg/mL of β-glucan. In keratinocytes (OBA-9), the expression of BCL-2, EP-300, and PTGS-2 decreased with the higher dose of β-glucan. Such genes are considered a marker for many dysfunctions, such as periodontal disease, due to their functions as inflammatory mediators. The modulation of gene expression these markers may indicate an improvement in inflammatory profile and a possible reduction in microbial activity.

Conclusions

Treatment with β-glucans from Saccharomyces cerevisiae administered for 24 h in a dual-chamber model positively modulated the immune response and metabolites production.

References

Javmen A, Nemeikaitė-Čėnienė A, Bratchikov M, Grigiškis S, Grigas F, Jonauskienė I, et al. β-Glucan from Saccharomyces cerevisiae Induces IFN-γ Production In Vivo in BALB/c Mice. In Vivo. 2016;29:359–63.

Kogan G, Kocher A. Role of yeast cell wall polysaccharides in pig nutrition and health protection. Livest Sci. 2007;109:161–5.

Vetvicka V. Glucan-immunostimulant, adjuvant, potential drug. World J Clin Oncol. 2011;2:115–9.

Talbott SM, Talbott JA, Talbott TL, Dingler E. β-Glucan supplementation, allergy symptoms, and quality of life in self-described ragweed allergy sufferers. Food Sci Nutr. 2013;1:90–101.

Masuda Y, Inoue H, Ohta H, Miyake A, Konishi M, Nanba H. Oral administration of soluble β-glucans extracted from Grifola frondosa induces systemic antitumor immune response and decreases immunosuppression in tumor-bearing mice. Int J Cancer. 2013;133:108–19.

Chen J, Zhang XD, Jiang Z. The application of fungal β-glucans for the treatment of colon cancer. Anticancer Agents Med Chem. 2013;13:725–30.

Loesche WJ, Syed SA, Schmidt E, Morrison EC. Bacterial profiles of subgingival plaques in periodontitis. J Periodontol. 1985;56:447–56.

Socransky SS, Haffajee AD. Evidence of bacterial etiology: a historical perspective. Periodontol. 1994;5:7–25.

Haffajee AD, Socransky SS. Microbial etiological agents of destructive periodontal diseases. Periodontol 2000. 1994;5:78–111.

Socransky SS, Haffajee AD, Cugini MA, Smith C, Kent RL. Microbial complexes in subgingival plaque. J Clin Periodontol. 1998;25:134–44.

Mintz KP. Identification of an extracellular matrix protein adhesin, EmaA, which mediates the adhesion of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans to collagen. Microbiology. 2004;150:2677–88.

Slots J, Reynolds HS, Genco RJ. Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans in human periodontal disease: a cross-sectional microbiological investigation. Infect Immun. 1980;29:1013–20.

Zambon JJ, Christersson LA, Slots J. Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans in human periodontal disease. Prevalence in patient groups and distribution of biotypes and serotypes within families. J Periodontol. 1983;54:707–11.

Haraszthy VI, Hariharan G, Tinoco EM, Cortelli JR, Lally ET, Davis E, et al. Evidence for the role of highly leukotoxic Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans in the pathogenesis of localized juvenile and other forms of early-onset periodontitis. J Periodontol. 2000;71:912–22.

Yang HW, Asikainen S, Doğan B, Suda R, Lai CH. Relationship of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans serotype b to aggressive periodontitis: frequency in pure cultured isolates. J Periodontol. 2004;75:592–9.

Gafan GP, Lucas VS, Roberts GJ, Petrie A, Wilson M, Spratt DA. Prevalence of periodontal pathogens in dental plaque of children. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:4141–6.

Cortelli SC, Costa FO, Kawai T, Aquino DR, Franco GCN, Ohara K, et al. Diminished treatment response of periodontally diseased patients infected with the JP2 clone of Aggregatibacter (Actinobacillus) actinomycetemcomitans. J Clin Microbiol. 2009;47:2018–25.

da Silva-Boghossian CM, do Souto RM, Luiz RR, Colombo APV. Association of red complex, A. actinomycetemcomitans and non-oral bacteria with periodontal diseases. Arch Oral Biol. 2011;56:899–906.

Fine DH, Velliyagounder K, Furgang D, Kaplan JB. The Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans autotransporter adhesin Aae exhibits specificity for buccal epithelial cells from humans and old world primates. Infect Immun. 2005;73:1947–53.

Wilson ME, Hamilton RG. Immunoglobulin G subclass response of juvenile periodontitis subjects to principal outer membrane proteins of Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans. Infect Immun. 1995;63:1062–9.

Henderson B, Ward JM, Ready D. Aggregatibacter (Actinobacillus) actinomycetemcomitans: a triple A* periodontopathogen? Periodontol 2000. 2010;54:78–105.

Herbert BA, Novince CM, Kirkwood KL. Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans, a potent immunoregulator of the periodontal host defense system and alveolar bone homeostasis. Mol Oral Microbiol. 2016;31:207–27.

Bodet C, Andrian E, Tanabe S-I, Grenier D. Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans lipopolysaccharide regulates matrix metalloproteinase, tissue inhibitors of matrix metalloproteinase, and plasminogen activator production by human gingival fibroblasts: a potential role in connective tissue destructio. J Cell Physiol. 2007;212:189–94.

Vieira Lobato R, De Oliveira Silva V, Francelino Andrade E, Ribeiro Orlando D, Gilberto Zangeronimo M, Vicente de Sousa R, et al. Metabolic Effects of B-Glucans (Saccharomyces Cerevisae) Per Os Administration in Rats With Streptozotocin-Induced Diabetes. Nutr Hosp. 2015;32:256–64.

Silva VDe O, Lobato RV, Andrade EF, de Macedo CG, Napimoga JTC, Napimoga MH, et al. β-Glucans (Saccharomyces cereviseae) Reduce Glucose Levels and Attenuate Alveolar Bone Loss in Diabetic Rats with Periodontal Disease. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0134742.

Benso B, Rosalen PL, Alencar SM, Murata RM. Malva sylvestris Inhibits Inflammatory Response in Oral Human Cells. An In Vitro Infection Model. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0140331.

Chen C, Kittichotirat W, Chen W, Downey JS, Si Y, Bumgarner R. Genome sequence of naturally competent Aggregatibacter actinomycetemcomitans serotype a strain D7S-1. J Bacteriol. 2010;192:2643–4.

Oda D, Watson E. Human oral epithelial cell culture I. Improved conditions for reproducible culture in serum-free medium. In Vitro Cell Dev Biol. 1990;26:589–95.

Kusumoto Y, Hirano H, Saitoh K, Yamada S, Takedachi M, Nozaki T, et al. Human gingival epithelial cells produce chemotactic factors interleukin-8 and monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 after stimulation with Porphyromonas gingivalis via toll-like receptor 2. J Periodontol. 2004;75:370–9.

Branco-de-Almeida LS, Murata RM, Franco EM, dos Santos MH, de Alencar SM, Koo H, et al. Effects of 7-epiclusianone on Streptococcus mutans and caries development in rats. Planta Med. 2011;77:40–5.

O’Brien J, Wilson I, Orton T, Pognan F. Investigation of the Alamar Blue (resazurin) fluorescent dye for the assessment of mammalian cell cytotoxicity. Eur J Biochem. 2000;267:5421–6.

Pasetto S, Pardi V, Murata RM. Anti-HIV-1 activity of flavonoid myricetin on HIV-1 infection in a dual-chamber in vitro model. PLoS One. 2014;9:e115323.

Pfaffl MW. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:e45.

Fiehn O, Kind T. Metabolite profiling in blood plasma. Methods Mol Biol. 2007;358:3–17.

Ferreira DF. Sisvar: a computer statistical analysis system. Ciência e Agrotecnologia. 2015;35:1039–42.

McCulloch CA, Bordin S. Role of fibroblast subpopulations in periodontal physiology and pathology. J Periodontal Res. 1991;26:144–54.

Jandinski JJ. Osteoclast activating factor is now interleukin-1 beta: historical perspective and biological implications. J Oral Pathol. 1988;17:145–52.

Hedges SR, Agace WW, Svanborg C. Epithelial cytokine responses and mucosal cytokine networks. Trends Microbiol. 1995;3:266–70.

Kinane DF, Winstanley FP, Adonogianaki E, Moughal NA. Bioassay of interleukin 1 (IL-1) in human gingival crevicular fluid during experimental gingivitis. Arch Oral Biol. 1992;37:153–6.

Sfakianakis A, Barr CE, Kreutzer DL. Actinobacillus actinomycetemcomitans-induced expression of IL-1alpha and IL-1beta in human gingival epithelial cells: role in IL-8 expression. Eur J Oral Sci. 2001;109:393–401.

Okamura H, Tsutsui H, Kashiwamura S, Yoshimoto T, Nakanishi K. Interleukin-18: a novel cytokine that augments both innate and acquired immunity. Adv Immunol. 1998;70:281–312.

Sonck E, Stuyven E, Goddeeris B, Cox E. The effect of beta-glucans on porcine leukocytes. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 2010;135:199–207.

Akramiene D, Kondrotas A, Didziapetriene J, Kevelaitis E. Effects of beta-glucans on the immune system. Medicina (Kaunas). 2007;43:597–606.

Sandvik A, Wang YY, Morton HC, Aasen AO, Wang JE, Johansen F-E. Oral and systemic administration of beta-glucan protects against lipopolysaccharide-induced shock and organ injury in rats. Clin Exp Immunol. 2007;148:168–77.

Di C-P, Sun Y, Zhao L, Li L, Ding C, Xu Y, et al. Effect of nifedipine on the expression of keratinocyte growth factor and its receptor in cocultured/monocultured fibroblasts and keratinocytes. J Periodontal Res. 2013;48:740–7.

Correia C, Lee S-H, Meng XW, Vincelette ND, Knorr KLB, Ding H, et al. Emerging understanding of Bcl-2 biology: Implications for neoplastic progression and treatment. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1853;2015:1658–71.

Shikama N, Lutz W, Kretzschmar R, Sauter N, Roth J-F, Marino S, et al. Essential function of p300 acetyltransferase activity in heart, lung and small intestine formation. EMBO J. 2003;22:5175–85.

Ghosh AK, Varga J. The transcriptional coactivator and acetyltransferase p300 in fibroblast biology and fibrosis. J Cell Physiol. 2007;213:663–71.

Deng W-G, Zhu Y, Wu KK. Role of p300 and PCAF in regulating cyclooxygenase-2 promoter activation by inflammatory mediators. Blood. 2004;103:2135–42.

Loo WTY, Wang M, Jin LJ, Cheung MNB, Li GR. Association of matrix metalloproteinase (MMP-1, MMP-3 and MMP-9) and cyclooxygenase-2 gene polymorphisms and their proteins with chronic periodontitis. Arch Oral Biol. 2011;56:1081–90.

Lazăr L, Loghin A, Bud ES, Cerghizan D, Horváth E, Nagy EE. Cyclooxygenase-2 and matrix metalloproteinase-9 expressions correlate with tissue inflammation degree in periodontal disease. Rom J Morphol Embryol. 2015;56:1441–6.

Lamberts L, Joye IJ, Beliën T, Delcour JA. Dynamics of γ-aminobutyric acid in wheat flour bread making. Food Chem. 2012;130:896–901.

Abey US, Sugimoto K, Hirawa KY, Yokoyma N, et al. Effect of green tea rich in ?-aminobutyric acid on blood pressure of Dahl salt-sensitive rats. Am J Hypertens. 1995;8:74–9.

Denda M, Inoue K, Inomata S, Denda S. gamma-Aminobutyric acid (A) receptor agonists accelerate cutaneous barrier recovery and prevent epidermal hyperplasia induced by barrier disruption. J Invest Dermatol. 2002;119:1041–7.

Hayakawa K, Kimura M, Kamata K. Mechanism underlying γ-aminobutyric acid-induced antihypertensive effect in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 2002;438:107–13.

Katagiri S, Nitta H, Nagasawa T, Izumi Y, Kanazawa M, Matsuo A, et al. Effect of glycemic control on periodontitis in type 2 diabetic patients with periodontal disease. J Diabetes Investig. 2013;4:320–5.

Oh C-H, Oh S-H. Effects of Germinated Brown Rice Extracts with Enhanced Levels of GABA on Cancer Cell Proliferation and Apoptosis. J Med Food. 2004;7:19–23.

Del Olmo A, Calzada J, Nuñez M. Benzoic Acid and Its Derivatives as Naturally Occurring Compounds in Foods and as Additives: Uses, Exposure and Controversy. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2015 [Epub ahead of print].

Numata A, Takahashi C, Fujiki R, Kitano E, Kitajima A, Takemura T. Plant constituents biologically active to insects. VI. Antifeedants for larvae of the yellow butterfly, Eurema hecabe mandarina, in Osmunda japonica. (2). Chem Pharm Bull. 1990;38:2862–5.

Geethan PKMA, Prince PSM. Antihyperlipidemic effect of D-pinitol on streptozotocin-induced diabetic Wistar rats. J Biochem Mol Toxicol. 2008;22:220–4.

Gao Y, Zhang M, Wu T, Xu M, Cai H, Zhang Z. Effects of D-Pinitol on Insulin Resistance through the PI3K/Akt Signaling Pathway in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Rats. J Agric Food Chem. 2015;63:6019–26.

Klukowska M, Goyal CR, Khambe D, Cannon M, Miner M, Gurich N, et al. Response of chronic gingivitis to hygiene therapy and experimental gingivitis. Clinical, microbiological and metabonomic changes. Am J Dent. 2015;28:273–84.

Barnes VM, Kennedy AD, Panagakos F, Devizio W, Trivedi HM, Jönsson T, et al. Global metabolomic analysis of human saliva and plasma from healthy and diabetic subjects, with and without periodontal disease. Yilmaz Ö, editor. PLoS One. 2014;9:e105181.

Acknowledgements

Research reported in this publication was supported by: National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health of the National Institutes of Health under award number R00AT006507, CAPES (Coordination of Improvement of Higher Education Personnel), FAPEMIG (Research Sponsoring Agency of the State of Minas Gerais) and CNPq (National Counsel of Technological and Scientific Development).

Funding

This work was supported by National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under award number R00AT006507. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors’ contributions

These authors contributed equally to this work. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Silva, V.d., Pereira, L.J. & Murata, R.M. Oral microbe-host interactions: influence of β-glucans on gene expression of inflammatory cytokines and metabolome profile. BMC Microbiol 17, 53 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12866-017-0946-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12866-017-0946-1