Abstract

Background

Treated wastewater effluent has been found to contain high levels of contaminants, including disease-causing bacteria such as Listeria and Aeromonas species. The aim of this study was to evaluate the antimicrobial resistance and virulence signatures of Listeria and Aeromonas spp. recovered from treated effluents of two wastewater treatment plants and receiving rivers in Durban, South Africa.

Methods

A total of 100 Aeromonas spp. and 78 Listeria spp. were positively identified based on biochemical tests and PCR detection of DNA region conserved in these genera. The antimicrobial resistance profiles of the isolates were determined using Kirby Bauer disc diffusion assay. The presence of important virulence genes were detected via PCR, while other virulence determinants; protease, gelatinase and haemolysin were detected using standard assays.

Results

Highest resistance was observed against penicillin, erythromycin and nalidixic acid, with all 78 (100 %) tested Listeria spp displaying resistance, followed by ampicillin (83.33 %), trimethoprim (67.95 %), nitrofurantoin (64.10 %) and cephalosporin (60.26 %). Among Aeromonas spp., the highest resistance (100 %) was observed against ampicillin, penicillin, vancomycin, clindamycin and fusidic acid, followed by cephalosporin (82 %), and erythromycin (58 %), with 56 % of the isolates found to be resistant to naladixic acid and trimethoprim. Among Listeria spp., 26.92 % were found to contain virulence genes, with 14.10, 5.12 and 21 % harbouring the actA, plcA and iap genes, respectively. Of the 100 tested Aeromonas spp., 52 % harboured the aerolysin (aer) virulence associated gene, while lipase (lip) virulence associated gene was also detected in 68 % of the tested Aeromonas spp.

Conclusions

The presence of these organisms in effluents samples following conventional wastewater treatment is worrisome as this could lead to major environmental and human health problems. This emphasizes the need for constant evaluation of the wastewater treatment effluents to ensure compliance to set guidelines.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Wastewater effluent and surrounding fresh water bodies such as rivers and estuaries have been found to contain high levels of contaminants, including disease-causing bacteria such as Listeria spp. and Aeromonas spp. [1]. The ability of these organisms to survive conventional wastewater treatment processes could lead to major environmental and human health problems, resulting from the highly contaminated surface waters [1]. Previously, Listeria has only been associated with food related infections and diseases, but has now been discovered and reported in water [2]. Of the seven recognised Listeria spp. (L. monocytogenes, L. ivanovii. L. innocua, L. seeligeri, L. welshimeri, L. grayii and L. murrayi), only L. monocytogenes and L. ivanovii are currently deemed as pathogenic and infectious, causing diseases in animals and human beings, since they are known to display β-haemolytic activity [3–6]. Listeria spp., mainly L. monocytogenes cause listeriosis which develops mostly in neonates, the elderly, pregnant women, and immuno-compromised individuals [2, 7]. Infection by L. monocytogenes occurs in several steps, each requiring expression of specific virulence factor. The major virulence genes are located in a cluster of genes on two different DNA loci and are mainly influenced by positive regulatory factor A protein. Important virulence factors have been characterised; listeriolysin O encoded by the gene hlyA and phosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase C encoded by the gene plcA. These genes play an important role in lysis of the phagosomes of the host cell and this makes the intracellular growth of Listeria cells possible [8, 9].

Aeromonads have grown in importance as food and waterborne pathogens, receiving much research attention since their discovery and implication in gastrointestinal diseases [10–12]. Seven Aeromonas spp., (A. hydrophila, A. caviae, A. veronii biovar sobria, A. veronii biovar veronii, A. jandaei, A. trota, and A. schubertii) are currently recognized as human pathogens [13]. Aeromonads are mesophilic bacteria which are found and widely distributed in soil and mostly aquatic (fresh, marine, estuarian) environments. They are mostly opportunistic microorganisms, mainly affecting individuals with reduced or compromised immunity, children and the elderly [14]. Aeromonas spp., have been widely reported in diarrheal diseases based on their common discovery in faecal samples of patients suffering from diarrhoea and other gastrointestinal diseases [14, 15]. The wide presence of potentially pathogenic Aeromonas spp. in freshwater bodies is of major public health concern [16]. A variety of potential virulence factors and toxins have been characterised in Aeromonas spp. [17], the most common ones being aer and hlyA gene which are responsible for aerolysin and hemolysin toxins production, respectively [18]. Aerolysin is one of the major virulence factors in gastroenteritis and in invasion of epithelial cells [19]. Some studies have reported high antimicrobial resistance patterns in Aeromonas spp., which increases the public threat, especially in cases of immunocompromised individuals with severe infections [16].

Wastewater treatment plants across South Africa have displayed poor bacterial pathogen removal over the years [1]. Furthermore, the current treatment regulations and guidelines mainly using common indicator organisms as a standard for monitoring drinking water and wastewater treatment processes have proven to be unreliable [20, 21]. This is of great public concern considering that an estimated 77 % of South Africans depend on surface water for most of their domestic water needs [22, 23]. Worse cases of waterborne infections have been seen and reported mostly in poverty stricken populations which lack adequate sanitation and infrastructure as surrounding populations have easy and uncontrolled access to free-flowing, highly contaminated waters to meet their water needs [1]. The prevalence of Listeria and Aeromonas spp. in treated wastewater effluent has been reported both in developing and developed countries [1, 2, 24]. Also, wastewater has been reported to be a potential reservoir and transporter of pathogenic Listeria and Aeromonas which harbour virulence determinants and display a notable trend of resistance to commonly used antimicrobial agents [2, 7, 24]. However, there is no report on the prevalence, antibiogram and virulence signatures of Listeria and Aeromonas spp. in effluent discharge of wastewater treatment plants in KwaZulu-Natal province of South Africa. This study therefore evaluated the antibiotic resistance phenotype and virulence properties of Listeria and Aeromonas spp. recovered from treated effluent of two wastewater treatment plants in Durban.

Methods

Water sampling and bacterial isolation

Wastewater and river samples were collected from two different wastewater treatment plants, designated as NWTW and NGWTW, located in the Durban area (KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa). Permissions were obtained from the relevant authority of both treatment plants to carry out water sampling. Water samples were collected before and after chlorination of the final treated effluent, and approximately 500 m up and downstream of discharge point into the receiving waters. Samples were serially diluted with sterile distilled water and 50 ml of the appropriate dilutions were filtered using standard 0.45 μm pore sized filters, according to standard membrane filtration methods. Membrane filters were then aseptically transferred onto Rimler-shotts agar (HIMEDIA, India) (incubated at 37 °C for 20 h) and Listeria Chromogenic agar (Oxoid, Cambridge, UK) (incubated at 35 °C for 24–48 h) for identification of Aeromonas spp and Listeria spp., respectively. Presumptive isolates with typical appearance on the respective medium (yellow for Aeromonas and blue for Listeria) were inoculated separately onto fresh selective media to obtain pure culture, before sub-culturing onto nutrient agar plates for identification.

Identification of the bacterial isolates

Biochemical identification of Listeria and Aeromonas spp.

Identification of the presumptive Aeromonas and Listeria spp. recovered from treated effluent and the receiving rivers was carried out using a range of biochemical tests, including oxidase, catalase, urease, carbohydrate fermentation, acid formation (TSI), indole production tests, Methyl red and Voges-Proskauer test [25, 26].

Molecular identification

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was used to amplify and detect the presence of specific conserved sequences in presumptive Listeria spp. and Aeromonas spp. isolates using primers List-universal 1 and 2, and gyrB3F and gyrB14R, respectively (Inqaba Biotech, SA) (Table 1). DNA was extracted using the boiling method according to Bai et al. modified protocol [27]. All PCR amplifications were performed in a thermal cycler (GeneAMP PCR System 2400, Bio-Rad). For the detection of iap gene in Listeria spp., PCR conditions were as follows: Pre-denaturation at 95 °C for 5 min, 30 cycles of; denaturation at 95 °C for 1 min, annealing at 36 °C for 1 min, extension at 72 °C for 3 min and final extension at 72 °C for 7 min [28]. PCR was performed in a final volume of 50 μl containing 50 mM KCl, 10 mM Tris/HCl (pH 8.3), 3.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 μM of each dNTPs (Thermo Scientific Fermenters, UK), 1.25 U Supertherm Taq DNA polymerase (Separation Scientific, Cape Town, SA), 0.2 μM of each primer (Inqaba Biotech, SA) and 1 μl of the extracted DNA sample [28]. Listeria monocytogenes ATCC 19115 was used as a positive control in all PCR assays. For the PCR amplification of gyrB gene in Aeromonas spp., the following conditions were applied: Pre-denaturation at 94 °C for 2 min, 30 cycles of; denaturation at 93 °C for 30 s, annealing at 62 °C for 30 s and extension at 72 °C for 1 min [29]. PCR was performed in a final volume of 50 μl containing 50 mM KCl, 10 mM Tris/HCl (pH 9), 1.5 mM MgCl2, 0.2 mM dNTPs (Thermo Scientific Fermenters, UK), 1U Supertherm Taq DNA polymerase (Separation Scientific, Cape Town, SA), 20 pmol of each primer (Inqaba Biotech, SA) and 1 μl of the extracted DNA sample [30]. Aeromonas caviae ATCC 15468 and Aeromonas hydrophila ATCC 7965 strain were used as positive controls.

Antimicrobial susceptibility determination

The Kirby Bauer Disk diffusion method [31, 32] was used to determine the antibiotic resistance profile of Listeria and Aeromonas spp. isolates. The isolates were screened against a panel of 24 antibiotics belonging to 14 different classes (Table 2). Cultures were grown for 24 h in Luria-Bertani broth and thereafter standardized to 0.5 McFarland standard (OD625nm = 0.08–0.1) using a spectrophotometer (Biochrom, Libras), before spreading on Mueller-Hinton agar plates using sterile swabs. The plates were then dried at room temperature for 15 min before placing 4 discs per plates at approximately 40 mm apart from each other. The plates were incubated for 18–24 h at 35–37 °C. Zones of clearance surrounding each disk were used to determine the level of susceptibility or resistance, and were scored based on the CLSI standards [31, 32] using Escherichia coli ATCC 25922 as standard for Gram negative and Staphylococcus aureus ATCC 25923 as a standard for Gram positive [33]. Multiple Antibiotic Resistance (MAR) index was calculated as follows: MAR = a/b, where a = number of antibiotics to which the isolate was resistant; b = total number of antibiotics against which individual isolate was tested.

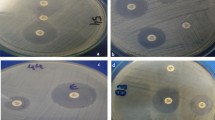

Protease, gelatinase and haemolysin assay

Protease activity was assayed by spreading bacterial strains on nutrient agar containing 1.5 % skim milk. After incubation at 30 °C for 72 h, the production of protease was shown by the formation of a clear zone caused by casein degradation. Gelatinase production was determined on LB agar containing gelatine (30 g/L). The plates were incubated at 30 °C for 24 h and cooled for 5 h at 4 °C. The appearance of turbid halos around the colonies was considered positive for gelatinase production [34]. Haemolysin production was assayed by culturing each strain on blood agar at 30 °C for 24 h. The production of haemolysin was observed by the formation of a clear zone caused by β-haemolysis activity of the enzyme on the blood (modified from Sechi et al. [35].

PCR detection of virulence genes

A multiplex PCR assay was used for the detection of four virulence-associated genes of L. monocytogenes namely, plcA, hlyA, actA and iap, coding for the phospholipase, haemolysin, intracellular motility and p60 invasion proteins, respectively [35] using the primer (Inqaba Biotech, SA) sets indicated in Table 1. The final reaction mixture (50 μl) contained: 1 × PCR buffer, 1 mM dNTP mix (Thermo Scientific Fermenters, UK), 6 mM MgCl2 and 10 μM of each primer sets, 4U of Supertherm Taq DNA polymerase (Separation Scientific, Cape Town, SA), 5 μl of DNA and sterilized water to make up the reaction volume. PCR was carried out in a Thermocycler (GeneAMP PCR System 2400, Bio Rad) under the conditions stated by Rawool et al. [35]. A monoplex PCR was used for the detection of two virulence-associated genes of Aeromonas spp. namely, aer and lip, coding for the aerolysin and lipase enzymes, respectively, using the primer sets (Inqaba Biotech, SA) indicated in Table 1. Each reaction was carried out in a total volume of 25 μl, containing 12.5 μl of the PROMEGA G2 Go Taq green master mix (ANATECH), 5 μl of isolated genomic DNA and sterile double distilled water to make up the reaction volume. PCR was carried out in a Thermocycler (GeneAMP PCR System 2400, Bio Rad) under the conditions stated by Igbinosa et al. [36].

Results

Identification of the presumptive Aeromonas and Listeria spp. isolates

Aeromonas spp. isolates were confirmed as either negative or positive for the biochemical tests conducted. Oxidase and catalase positive, urease negative, Methyl red positive and Voges-Proskauer negative organisms were confirmed as Aeromonas spp. The gyrB gene region was successfully amplified in positive isolates with the expected product size (1100 bp), as shown in Fig. 1a. Biochemical reaction of Listeria isolates was shown by oxidase negative, catalase positive and Methyl red and Voges-Proskauer positive. All positively identified Listeria spp. isolates were further confirmed by PCR, with the expected amplicon sizes (457–610 bp, commonly 457 bp) of the universal conserved iap gene obtained (Fig. 1b).

a. Agarose gel showing PCR amplicons of the gyrB gene of representative Aeromonas spp. isolates (lanes 2–17), M: 100 pb molecular marker and lane 1: negative control. b. Agarose gel showing PCR amplicons of the iap gene of representative Listeria spp. isolates (lanes 2–9), M: molecular marker and lane 1: negative control

Antimicrobial resistance profiles of Listeria and Aeromonas spp. isolates

The resistance and susceptibility profiles of Listeria spp. and Aeromonas spp. isolates against a broad range of antimicrobials commonly used for Enterobacteria are shown in Table 2. Among Listeria spp., the highest resistance (100 %) was observed against penicillin, erythromycin and nalidixic acid, followed by ampicillin (83.33 %), trimethoprim (67.95 %), nitrofurantoin (64.10 %) and cephalosporin (60.26 %). Of the 78 tested Listeria spp. isolates, all (100 %) were found to be sensitive to 5 of the antibiotics: streptomycin, chloramphenicol, fosfomycin, fusidic acid and amikacin, followed by ciprofloxacin (96.15 %), gentamicin (92.31 %), mixofloxacin (92.31 %), meropenem (89.74 %), clindamycin (88.46 %) and colistin (79.48 %). All the tested isolates showed resistance to at least 5 of the 24 antibiotics, with 4 (5.13 %) of the test isolates displaying resistance to at most 12 of the 24 antibiotics as shown in Table 2. The antibiotic resistance index (ARI) for the Listeria spp. ranged between 0.13 (resistance to 3 test antibiotics) and 0.5 (resistance to 12 of the test antibiotics). The multidrug resistance patterns of the Listeria spp. as shown in Fig. 2a, revealed that at least 1 (1.28 %) of the isolates was resistant to 3–4 antibiotic classes, with most of the multidrug resistant isolates being resistant to at least more than 5 and at most 11 antimicrobial classes. The highest multidrug resistance patterns was observed in 3 (3.85 %) of the 78 tested Listeria spp isolates, being resistant to 11 of the 24 tested antibiotics, while the highest percentage resistance (to 9 antimicrobial classes) was observed in 19 (24.36 %) isolates (Fig. 2a).

The resistance and susceptibility profiles of the 100 Aeromonas spp. isolates tested against a broad range of antimicrobials commonly used for the treatment of Enterobacteria-associated infections are shown in Table 2. The highest resistance (100 %) was observed for ampicillin, penicillin, vancomycin, clindamycin and fusidic acid, followed by cephalothin (82 %), and erythromycin (58 %), with 56 % of the isolates found to be resistant to nalidixic acid and trimethoprim. All the isolates were found to be sensitive to gentamycin, 95 % to amikacin and chloramphenicol, while 94, 88, 86, 83 and 82 % of the isolates were susceptible to ciprofloxacin, fosfomycin, colistin, mixofloxacin and cefotaxime, respectively. All the tested isolates showed resistance to at least 6 of the 24 antibiotics, with 5 of the test isolates displaying resistance to 14 of the 24 antibiotics as shown in Table 2. The multidrug resistance patterns of Aeromonas spp. displayed in Fig. 2b), show that most of the multidrug resistant isolates were resistant to at least 6 and at most 14 classes of antimicrobials, with the ARI ranging from 0.25 to 0.58. The highest multidrug resistance pattern (to 14 antimicrobial classes) was observed in 5 % of the test isolates, while 29 % of the tested isolates were resistant to 8 antimicrobial classes (Fig. 2b).

Virulence gene signatures of the Listeria and Aeromonas spp. isolates

The agarose gel showing the expected amplicon sizes of virulence associated gene products detected in some Listeria spp. isolates is represented in Fig. 3a. The primer sets allowed for the amplification of 1484 bp (plcA), 839 bp (actA) and 131 bp (iap) from the DNA template. Of the 78 tested Listeria spp., 21 (26.92 %) were found to contain virulence genes, with 14.10, 5.12 and 21 % of these species found to harbour actA, plcA and iap genes, respectively (Fig. 3a). Furthermore, 9 (11.54 %) of the isolates contained more than one virulence gene (actA and iap genes). PCR amplicons of the expected sizes of the aer gene (431 bp) and lip gene (247) in Aeromonas spp. is represented in Fig. 3b and c, respectively. Of the 100 tested Aeromonas spp., 52 % were found to harbour the aer virulence associated gene, while 68 % harboured lip virulence associated gene, with 29 isolates found to contain both the aer and lip genes.

a. Agarose gel showing PCR amplicons of three virulence associated genes (plcA, actA, and iap) detected in representative Listeria spp. (lanes 1 & 3) and L. monocytogenes (ATCC 19115) (Lane 2). M: DNA marker (100 to 3000 bp) and Lane 4: negative control. b. Agarose gel showing PCR amplicons of the Aerolysin (aer) virulence associated gene of representative Aeromonas spp., M: DNA marker (100 bp), lane 1–7: amplified PCR products, Lane 8: negative control. c. Agarose gel showing PCR amplicons of the Lipase (lip) virulence associated gene of representative Aeromonas spp., M: DNA marker (100 bp), lane 1–17: amplified PCR products

Protease, gelatinase and haemolysin production

Blood agar plates were hydrolysed by 25 (32 %) of the tested Listeria spp. by the formation of clear zones around the colonies indicating a positive result for the production of the haemolysin enzyme. However, all the Listeria isolates tested negative for gelatinase and protease enzyme production. All the 100 tested Aeromomonas spp. isolates tested positive for protease enzyme production, while 67 and 88 % of the isolates tested positive for the production of haemolysin and gelatinase, respectively.

Discussion

The successful identification of the Aeromonas and Listeria spp using the biochemical and molecular methods indicates the prevalence of emerging bacterial pathogens in treated wastewater effluent, reiterating the fact that they are able to withstand and survive conventional wastewater treatment processes as previously reported [1, 13, 37, 38]. The observed highest resistance (100 %) of Aeromonas spp. against ampicillin, penicillin, vancomycin, clindamycin and fusidic acid in this study was in line with those reported in similar studies [13, 37, 39, 40], where ampicillin and vancomycin were amongst the antibiotics which had no antimicrobial activity towards tested Aeromonas spp. isolates. However, Goni-Urriza et al. [41] and P´erez-Valdespino et al. [42], did not observe complete resistance of Aeromonas spp. tested to these antibiotics, but a similar trend of high resistance levels was observed. Also, the high sensitivity patterns observed against gentamicin, fosfomycin, cefotaxime, amikacin, and meropenem in this study were comparable to previous findings [13, 39].

The susceptibility patterns of Listeria spp. obtained in this study are similar to those reported by Odjadjare and Okoh [1], who tested 23 Listeria isolates against 20 antibiotics and found that all tested isolates were sensitive to 3 of the 20 test antibiotics including amikacin (aminoglycosides), meropenem, and ertapenem (carbapenems) suggesting that these antibiotics may be the best therapy in the event of listeriosis outbreak in South Africa. In general, L. monocytogenes, as well as other strains of Listeria spp., are susceptible to a wide range of antibiotics [43], however a notable increased resistance has been observed over the past couple of years [44]. Studies have also described the transfer, by conjugation, of enterococcal and streptococcal plasmids and transposons carrying antibiotic resistance genes to Listeria from closely related bacteria such as Enterococcus, Streptococcus and Staphylococcus spp. [45] and between species of Listeria [46]. L. monocytogenes may acquire or transfer antibiotic resistance gene from mobile genetic elements such as self-transferable and mobilizable plasmids and conjugative transposons or mutational events in chromosomal genes [47]. High sensitivity levels of Listeria spp. towards the β-Lactams (penicillins, cephalothins) and penicillins have been reported in literature, and these antibiotics are therefore considered as the main treatment drug for listeriosis [33, 48–51]. In contrast, results obtained in this study revealed high resistance levels towards the β-Lactams: penicillin (100 %), cephalothin (60.26 %) and ampicillin (83.33 %). Arslan and Ozdemir [7] also reported resistance against ampicillin (2.1 %) and penicillin (12.8 %) in strains of Listeria spp. isolated from white cheese.

It has been widely reported that conventional wastewater treatment plants are unable to effectively remove antimicrobials such as antibiotics as well as a number of other chemicals from wastewater, thereby increasing the chances of bacterial pathogens resident in such wastewater effluent to acquire resistance to commonly used antibiotics due to selective pressures [52–54]. Medical and pharmaceutical discharge from hospitals has largely contributed to the increase in antibiotic concentration and therefore has led to the rise of highly resistant bacterial populations [55]. Wastewater treatment plants have therefore been considered as a rich reservoir of antibiotic and multidrug resistant organisms since the antibiotics ingested by humans are not completely processed by the body. Some of these antibiotics are expelled as waste and wind up at wastewater treatment plants [43, 56]. Rivers contaminated with urban and agricultural effluent have shown to have greater antibiotic resistant bacterial populations than areas upstream of the contamination source [57]. Antibiotic resistance in streams is also indirectly selected for by an increase in industrial wastes containing heavy metals, which could probably explain the findings of this study since both wastewater treatment plants investigated are surrounded by industrial areas, receiving wastes containing carcinogenic heavy metals and toxic chemicals as well hospital effluents. Recent findings suggest an increase in the level of multi-antibiotic resistance over the last few years [33, 58–60]. It is therefore not surprising that a high prevalence of multi-antimicrobial resistance was observed among the Listeria spp. in this study.

The infection or pathogenicity process of Aeromonas spp. is very complex and is said to involve different virulent and pathogenicity factors which either act together or separately at different stages of infection. Aerolysin gene is responsible for most of the haemolytic, cytotoxic and enterotoxic activities, which play a vital role in the initial stages of the host infection process [36, 61]. This gene was detected in 52 % of the isolates, similar to the findings of Igbinosa and Okoh [36] who reported a high presence (43 %) of the aer gene in Aeromonas spp. isolated from water samples in South Africa. Similarly, Soler et al. [62] detected this gene in 26 % of the tested environmental Aeromonas isolates. The presence of this aer gene in 52 % of the Aeromonas spp. obtained from treated wastewater effluent and receiving river water indicates that the isolates investigated in this study are potentially pathogenic and virulent strains of either A. hydrophila, A. caviae and A. veroni, where this gene is commonly found [18]. High numbers of virulence gene - containing Aeromonas spp. have been observed in multiple studies, involving environmental samples, with reports from Brazil, India, Italy and Spain alike [63–65]. The lip gene which primarily plays an integrated and coherent role in pathogenicity of Aeromonas spp. was detected in 68 % of the isolates. This gene is responsible for altering the host’s plasma membranes, thus increasing the severity of the infection [66–69].

In this study, some of the tested Listeria species were found to harbour the actA, plcA and iap genes, classifying them as possibly L. monocytogenes, L. ivanovii and L. seeligeri, species known to harbour these genes [35]. The haemolytic activity demonstrated by these Aeromonas spp. on human red blood cells is indicative of the production of the haemolysin virulence factor. Several authors have suggested that this virulence determinant is usually associated with strains of A. hydrophila and A. sobria [70–72], which are potential human pathogens. The link between haemolytic activity and enterotoxigenicity observed in this study has been well documented [71, 72]. Results obtained in this study indicate a possible presence of virulent Listeria and Aeromonas spp, which could be detrimental to the users of the receiving rivers upon exposure.

Conclusion

The high prevalence of multi-antimicrobial resistant Aeromonas and Listeria spp. harbouring resistance genes obtained in this study is indicative of the severity of the threat these pathogens might pose to the health of the environment and other organisms exposed to the contaminated waters. Apart from the two reported emerging bacterial pathogens (Aeromonas and Listeria spp), other common bacterial indicators of water pollution, viz., E. coli, total coliforms, faecal coliforms, faecal Streptococci, Salmonella spp, Shigella spp, and Vibrio spp as well as other emerging bacterial pathogens including Yersinia spp , Legionella spp., Pseudomonas spp. were also detected in the treated effluent of these plants (Results not shown). This further confirmed previous report indicating a low reduction of microbes by treatment plants resulting in poor effluent quality with load of infectious microorganisms [73]. This is of great concern as most of the surface water samples were collected from locations which were easily accessible to animals and human populations residing in informal settlements along the river. Multidrug resistant organisms found in this study were also resistant to some of the commonly used antibiotics and this is particularly worrisome in a province with a high number of immunocompromised individuals due to the high HIV and TB pandemic as this will impact on treatment regime. Findings from this study further highlight the need for the Department of Water Affairs to revise the current guidelines and standards to include the emerging bacterial pathogens, which are often detected even in the absence of commonly used indicator organisms. There is also need for constant evaluation of the wastewater treatment plants to ensure efficiency and compliance to set guidelines in order to protect public and environmental health.

Abbreviations

- aer :

-

Aerolysin

- ARI:

-

Antibiotic resistance index

- gyrB :

-

Gyrase B

- hlyA :

-

Hemolysin

- lip :

-

Lipase

- actA :

-

Actin assembly-inducing protein

- iap :

-

p60 invasion proteins

- plcA :

-

Phospholipase

- MAR:

-

Multiple antibiotic resistance

- PCR:

-

Polymerase chain reaction

References

Odjadjare EEO, Okoh AI. Prevalence and distribution of Listeria pathogens in the final effluents of a rural wastewater treatment facility in the Eastern Cape Province of South Africa. World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2010;26:297–307.

Paillard D, Dubois V, Thiebaut R, Nathier F, Hoogland E, Caumette P, et al. Occurrence of Listeria spp. in effluents of French urban wastewater treatment plants. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005;71:7562–6.

Brugere-Picoux O. Ovine listeriosis. Small Ruminant Res. 2008;76:12–20.

Roberts AJ, Wiedmann M. Pathogen, host and environmental factors contributing to the pathogenesis of listeriosis. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2003;60:904–18.

Rodriguez-Lázaro D, Hernandez M, Scortti M, Esteve T, Vázquez-Boland JA, Pla M. Quantitative detection of Listeria monocytogenes and Listeria innocua by real-time PCR: assessment of hly, iap, and lin02483 targets and AmpliFluor technology. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2004;70:1366–77.

Schuchat A, Swaminathan B, Broome CV. Epidemiology of human listeriosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1991;4:169–83.

Arslan S, Ozdemir F. Prevalence and antimicrobial resistance of Listeria spp. in homemade white cheese. Food Control. 2008;19:360–3.

Marquis H, Doshi V, Portnoy DA. The broad range phospholipase C and a metalloprotease mediate listeriolysin O-independent escape of Listeria monocytogenes from a primary vacuole in human epithelial cells. Immunol Infect. 1995;63:4531–4.

Sibelius U, Schulz EC, Rose F, Hattar K, Jacobs T, Weiss S, et al. Role of Listeria monocytogenes exotoxins listerolysin and phosphatidylinositol-specific phospholipase C in activation of human neutrophils. Infect Immunol. 1999;67:1125–30.

Ansari M, Rahimi E, Raissy M. Antibiotic susceptibility and resistance of Aeromonas spp. isolated from fish. Afr J Microbiol Res. 2011;5:5772–5.

Ghenghesh KS, Ahmed SF, El-Khalek RA, Al-Gendy A, Klena J. Aeromonas infections in developing countries. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2008;2:81–98.

Holmberg SD, Schell WL, Fanning GR. Aeromonas intestinal infections in the United States. Ann Intern Med. 1986;105:683–9.

Obi CL, Ramalivhana J, Samie A, Igumbor EO. Prevalence, pathogenesis, antibiotic susceptibility profiles, and in-vitro activity of selected medicinal plants against Aeromonas isolates from stool samples of patients in the Venda Region of South Africa. J Health Popul Nutr. 2007;25:428–35.

Igbinosa IH, Igumbor EU, Aghdasi F, Tom M, Okoh AI. Emerging Aeromonas species infections and their significance in public health. Sci World J. 2012;2012:1–13.

Vila J, Marco F, Soler L, Chacon M, Figueras M. J. Aeromonas spp. and traveler’s diarrhea: clinical features and antimicrobial resistance. Emerg Infect Dis. 2003;9:552–5.

Obi CL, Igumbor JO, Momba MNB, Samie A. Interplay of factors involving chlorine dose, turbidity flow capacity and pH on microbial quality of drinking water in small treatment plants. Water SA. 2008;34:565–72.

Biscardi D, Castaldo A, Gualillo O, de Fusco R. The occurrence of cytotoxic Aeromonas hydrophila strains in Italian mineral and thermal waters. Sci Total Environ. 2002;292:255–63.

Yousr AH, Napis S, Rusul GRA, Son R. Detection of Aerolysin and Hemolysin genes in Aeromonas spp. isolated from environmental and shellfish sources by polymerase chain reaction. ASEAN Food J. 2007;14:115–22.

Chu WH, Lu CP. Multiplex PCR assay for the detection of pathogenic Aeromonas hydrophila. J Fish Dis. 2005;28:437–41.

Eze E, Eze U, Eze C, Ugwu K. Association of metal tolerance with multidrug resistance among bacteria isolated from sewage. JRTPH. 2009;8:25–9.

Toze S. Reuse of effluent water – benefits and risk. CSIRO Land and Water report. Agric Water Manage. 2006;80:147–59.

Luyt CD, Tandlich R, Muller WJ, Wilhelmi BS. Microbial monitoring of surface water in South Africa: an overview. Int J Environ. 2012;9:2669–93. doi:10.3390/ijerph9082669.

Water UN. Water a shared responsibility. 2006. Retrieved from http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0014/001454/145405e.pdf#page=519. Accessed 1 June 2015.

Czeszejko K, Boguslawska-Was E, Dabrowski W, Kaban S, Umanski R. Prevalence of Listeria monocytogenes in municipal and industrial sewage. Electron J Pol Agric Univ Environ Dev. 2003;6:1–8.

Abbott SL, Cheung WKW, Janda JM. The genus Aeromonas: biochemical characteristics, atypical reactions, and phenotypic identification schemes. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:2348–57.

Gasanov U, Hughes D, Hansbro PM. Methods for the isolation and identification of Listeria spp. and Listeria monocytogenes: a review. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2005;29:851–75.

Bai J, Shi X, Nagaraja TG. A multiplex PCR procedure for the detection of six major virulence genes in Escherichia coli O157:H7. J Microbiol Meth. 2010;82:85–9.

Cocolin LK, Rantsiou L, Iacumin C, Cantoni, Comi G. Direct identification in food samples of Listeria spp. and Listeria momocytogenes by molecular methods. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2002;68:6273–82.

Huddleston JR, Zak JC, Jeter RM. Antimicrobial susceptibilities of Aeromonas spp. isolated from environmental sources. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2006;72:7036–42.

Yàñez MA, Catala´n V, Apra´iz D, Figueras MJ, Martı´nez- Murcia AJ. Phylogenetic analysis of members of the genus Aeromonas based on gyrB gene sequences. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2003;53:875–83.

CLSI. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing; fifteenth informational supplement. Wayne: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2005. M100-S15, 25: 163.

Balachandran C, Duraipandiyan D, Emi N, Ignacimuthu S. Antimicrobial and cytotoxic properties of Streptomyces sp. (ERINLG-51) isolated from Southern Western Ghats. South Indian J Biol Sci. 2015;1:7–14.

Zuraini MI, Maimunah M, Sharifah Aminah SM, Noor MM, Lee HY, Son R. Antibiogram Profiles of Listeria monocytogenes isolated from foods. Second International Conference on Biotechnology and Food Science, vol. 7. IACSIT Press, Singapore .2001. p. 133–7.

Sechi LA, Deriu A, Falchi MP, Fadda G, Zanetti S. Distribution of virulence genes in Aeromonas sp. isolated from Sardinian waters and from patients with diarrhoea. J Appl Microbiol. 2002;92:221–7.

Rawool DB, Malik SVS, Barbuddhe SB, Shakuntala I, Aurora R. A multiplex PCR for detection of virulence associated genes in Listeria monocytogenes. J Food Saf. 2007;9:56–62.

Igbinosa IH, Okoh AI. Detection and distribution of putative virulence associated genes in Aeromonas species from freshwater and wastewater treatment plant. J Basic Microbiol. 2013;53:895–901.

Lafdal MY, Malang S, Toguebaye BS. Antimicrobial susceptibility of aeromonads and coliforms before and after municipal wastewater treatment by activated sludge under arid climate. Int J Microbiol Res. 2012;3:174–80.

Martone-Rocha S, Piveli RP, Matté GR, Dória M, Dropa MC, Morita M, et al. Dynamics of Aeromonas species isolated from wastewater treatment system. J Water Health. 2010;8:703–11.

Igbinosa IH, Okoh AI. Antibiotic susceptibility profile of Aeromonas species isolated from wastewater treatment plant. Sci World J. 2012;12:1–6.

Vandan N, Ravindranath S, Bandekar JR. Prevalence, characterization, and antimicrobial resistance of Aeromonas strains from various retail food products in Mumbai, India. Indian J Food Sci. 2011;76:486–92.

Goni-Urriza M, Capdepuy M, Arpin C, Raymond N, Caumette P, Quentin C. Impact of an urban effluent on antibiotic resistance of riverine Enterobacteriacae and Aeromonas, spp. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2000;66:125–32.

P´erez-Valdespino A, Fern´andez-Rend E, Curiel-Qesada E. Detection and characterization of class 1 integrons in Aeromonas spp. isolated from human diarrheic stool in Mexico. J Basic Microbiol. 2009;49:572–8.

Adetunji VO, Isola TO. Antibiotic resistance of Escherichia coli, Listeria and Salmonella isolates from retail meat tables in Ibadan municipal abattoir, Nigeria. Afr J Biotechnol. 2011;10:5795–9.

Marian MN, Sharifah-Aminah SM, Zuraini MI, Son R, Maimunah M, Lee HY. MPN-PCR detection and antimicrobial resistance of Listeria monocytogenes isolated from raw and ready-to-eat foods in Malaysia. Food Control. 2012;28:309–14.

Safdar A, Armstrong D. Antimicrobial activities against 84 Listeria monocytogenes isolates from patients with systemic listeriosis at a comprehensive cancer center (1955–1997). J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:483–5.

Charpentier E, Courvalin P. Antibiotic Resistance in Listeria spp. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1999;43:2103–8.

Steve H, Imane S, Omar Z, Elias B, Elie, Nisreen A. Antimicrobial resistance of Listeria monocytogenes isolated from dairy-based food products. Sci Total Environ. 2009;407:4022–7.

Abuin CMF, Fernandez EJQ, Sampayo CF, Otero JTR, Rodriguez LD, Cepeda S. Susceptibilities of Listeria species isolated from food to nine antimicrobial agents. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1994;38:1655–7.

Conter M, Paludi D, Zanardi E, Ghidini S, Vergara A, Ianieri A. Characterization of antimicrobial resistance of foodborne Listeria monocytogenes. Int J Food Microbiol. 2009;128:497–500.

Hansen JM, Gerna-Smidt P, Bruun B. Antibiotic susceptibility of Listeria monocytogenes in Denmark 1958–2001. Acta Pathol Microbiol Immunol Scand. 2005;113:31–6.

Zhang Y, Yeh E, Hall G, Cripe J, Bhagwat A, Meng J. Characterization of Listeria monocytogenes isolated from retail foods. Int J Food Microbiol. 2007;113:47–53.

Giger W, Alder AC, Golet EM, Kohler HE, McArdell CS, Molnar E, et al. Occurrence and fate of antibiotics as trace contaminants in wastewaters, sewage sludges, and surface waters. Chimia. 2003;57:485–91.

Kummerer K. Significance of antibiotics in the environment. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2003;52:5–7.

Volkmann H, Schwartz T, Bischoff P, Kirchen S, Obst U. Detection of clinically relevant antibiotic-resistance genes in municipal wastewater using real-time PCR (TaqMan). J Microbiol Methods. 2004;56:277–86.

Naviner M, Gordon L, Giraud E, Denis M, Mangion C, Le Bris H, et al. Antimicrobial resistance of Aeromonas spp. isolated from the growth pond to the commercial product in a rainbow trout farm following a flumequine treatment. Aquaculture. 2011;315:236–41.

Jury KL, Vancov T, Stuetz RM, Khan SJ. Antibiotic resistance dissemination and sewage treatment plants. In: Current research, technology and education topics in applied microbiology and microbial biotechnology. 2010. p. 509–19.

Falcão JP, Brocchi M, Proenc¸a-Mo´dena JL, Acrani GO, Correˆa EF, Falcão DP. Virulence characteristics and epidemiology of Yersinia enterocolitica and Yersiniae other than Y. pseudotuberculosis and Y. pestis isolated from water and sewage. J Appl Microbiol. 2004;96:1230–6.

Ebrahim R, Mehrdad A, Hassan M. Prevalence and antimicrobial resistance of Listeria species isolated from milk and dairy products in Iran. Food Control. 2010;21:1448–52.

Mauro C, Domenico P, Emanuela Z, Sergio G, Albert V, Adriana I. Characterization of antimicrobial resistance of foodborne Listeria monocytogenes. Int J Food Microbiol. 2008;128:497–500.

Pesavento G, Ducci B, Nieri D, Comodo N, Lo Nostro A. Prevalence and antibiotic susceptibility of Listeria spp. isolated from raw meat and retail foods. Food Control. 2010;21:708–13.

Chopra AK, Houston CW, Peterson JW, Jin GF. Cloning, expression, and sequence analysis of a cytolytic enterotoxin gene from Aeromonas hydrophila. Can J Microbiol. 1993;39:513–23.

Soler L, Figueras MJ, Chacón MR, Vila J. Potential virulence and antimicrobial susceptibility of Aeromonas popoffii recovered from freshwater and seawater. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 2002;32:243–7.

Balsalobre LC, Dropa M, Matté GR, Matté MH. Molecular detection of enterotoxins in environmental strains of Aeromonas hydrophila and Aeromonas jandaei. J Water Health. 2009;7:685–91.

Ottaviani D, Parlani C, Citterio B, Masini L, Leoni F, Canonico C, et al. Putative virulence properties of Aeromonas strains isolated from food environmental and clinical sources in Italy: a comparative study. Int J Food Microbiol. 2011;144:538–45.

Sinha I, Choudhary I, Virdi JS. Isolation of Yersinia enterocolitica and Yersinia intermedia from wastewaters and their biochemical and serological characteristics. Curr Sci. 2000;74:510–3.

Chuang YC, Chiou SF, Su JH, Wu ML, Chang MC. Molecular analysis and expression of the extracellular lipase of Aeromonas hydrophila MCC-2. Microbiology. 1997;143:803–12.

Nawaz M, Khan SA, Khan AA, Sung K. Detection and characterization of virulence genes and integrons in Aeromonas veronii isolated from catfish. Food Microbiol. 2010;27:327–31.

Pemberton JM, Kidd SP, Schmidt R. Secreted enzymes of Aeromonas. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1997;152:1–10.

Lee KK, Ellis AE. Glycerophospholipid: cholesterol acyltransferase complexed with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) is a major lethal exotoxin and cytolysin of Aeromonas salmonicida: LPS stabilizes and enhances toxicity of the enzyme. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:5382–93.

Albert MJ, Ansaruzzaman M, Talukder KA, Chopra AK, Kuhn I, Rahman M. Prevalence of enterotoxin genes in Aeromonas spp. isolated from children with diarrhea, healthy controls, and the environment. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:3785–90.

Kudinha T, Tswana SA, Simango C. Virulence properties of Aeromonas strains from humans, animals and water. South Afr J Epidemiol Infect. 2000;15:94–7.

Monfort P, Baleux B. Haemolysin occurrence among Aeromonas hydrophila, Aeromonas caviae and Aeromonas sobria strains isolated from different aquatic ecosystems in Denmark. 2001. Acta Pathol Microbiol Immunol Scand. 2001;113:31–6.

Manonmani P, Raj SP, Ramar M, Erusan RR. Load of infectious microorganisms in hospital effluent treatment plant in Madurai. South Indian J Biol Sci. 2015;1:30–3.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the Medical Research Council and National Research Foundation of South Africa.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

AO conceived of the study, and participated in its design and coordination, interpretation of data and critical review of draft manuscript for intellectual content. SBT was involved in acquisition and analysis of data, statistical analysis and manuscript draft. NG participated in data analysis, statistical analysis, drafting and critical revision of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Olaniran, A.O., Nzimande, S.B.T. & Mkize, N.G. Antimicrobial resistance and virulence signatures of Listeria and Aeromonas species recovered from treated wastewater effluent and receiving surface water in Durban, South Africa. BMC Microbiol 15, 234 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12866-015-0570-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12866-015-0570-x