Abstract

Background

Diarrhoeal diseases are attributable to unsafe water stemming from improper sanitation and hygiene and are reportedly responsible for extensive morbidity and mortality particularly among children in developed and developing countries.

Methods

Water samples from selected rivers in Osun State, South-Western Nigeria were collected and analyzed using standard procedures. Escherichia coli isolates (n=300) were screened for 10 virulence genes using polymerase chain reaction for pathotyping.

Results

While the virulence gene (VG) lt for enterotoxigenic E. coli had the highest prevalence of 45 %, the enteropathogenic E. coli genes eae and bfp were detected in 6 and 4 % of the isolates respectively. The VGs stx1 and stx2 specific for the enterohemorrhagic E. coli pathotypes were detected in 7 and 1 % of the isolates respectively. Also, the VG eagg harboured by enteroaggregative pathotype and diffusely-adherent E. coli VG daaE were detected in 2 and 4 % of the isolates respectively and enteroinvasive E. coli VG ipaH was not detected. In addition, the VGs papC for uropathogenic and ibeA for neonatal meningitis were frequently detected in 19 and 3 % of isolates respectively.

Conclusions

These findings reveal the presence of diarrhoeagenic and non-diarrhoeagenic E. coli in the selected rivers and a potential public health risk as the rivers are important resources for domestic, recreational and livelihood usage by their host communities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Globally, diarrhoeal diseases and other related gastrointestinal illnesses constitute one of the most important causes of illness and death in the world particularly among infants and young children [1–3], with most of such illnesses contracted through ingestion of polluted waters. Ascertaining the qualities of fresh and marine waters relies heavily on the use of Escherichia coli and Enterococcus spp. commonly found in mammalian faeces [4, 5]. Escherichia coli is the most abundant facultative anaerobe. Most are commensals in the human intestinal microflora, but certain strains have virulence properties that may account for life-threatening infections. The pathogenicity of a particular E. coli strain is primarily determined by specific virulence factors which include adhesins, invasins, haemolysins, toxins, effacement factors, cytotoxic necrotic factors and capsules [6, 7], and these have been implicated in human and animal diseases worldwide with the pathogenic strains being categorized into intestinal pathogenic E. coli (InPEC) and extra-intestinal pathogenic E. coli (ExPEC) on the basis of their virulence factors and clinical symptoms [8, 9]. InPEC can be further classified into enterotoxigenic E. coli (ETEC), enteropathogenic E. coli (EPEC), enterohemorrhagic E. coli (EHEC), enteroinvasive E. coli (EIEC), enteroaggregative E. coli (EAEC) and diffusely adherent E. coli (DAEC) [9–11], and ExPEC into uropathogenic E. coli (UPEC), neonatal meningitis E. coli (NMEC) and avian pathogenic E. coli (APEC). Other diarrhoeagenic E. coli pathotypes have been proposed, such as cell-detaching E. coli (CDEC); however their significance remain uncertain [2, 12].

Common reservoirs of ETEC and EPEC include humans, ruminants, porcine, other domesticated animals such as goats, dogs and cats [10, 13, 14]. EHEC have been isolated from various ruminants, primarily cattle [15]. The principal reservoir for EIEC, EAEC and DAEC are humans [9, 13]. While UPEC and NMEC are commonly isolated from humans, APEC have been attributed to avian infections from poultry [9, 16]. Enterotoxigenic E. coli (ETEC) have been found associated with infantile and traveler’s diarrhoea; EPEC with acute infantile diarrhoea; EHEC with sporadic outbreaks of haemorrhagic colitis and hemolytic-uremic syndrome in humans; EAEC with persistent gastroenteritis and diarrhoea in infants and children and is prevalent in developing countries; and EIEC produces shigellosis-like diseases in children and adults, with invasive intestinal infections, watery diarrhoea, and dysentery in humans and animals [9, 10]. DAEC strains have also been associated with diarrhoeal disease in different geographic areas [17]. Uropathogenic E. coli (UPEC) enters the urinary tract and travels to the bladder to cause cystitis and, if left untreated, can ascend further into the kidneys to cause pyelonephritis. Septicaemia can occur with both UPEC and neonatal meningitis NMEC, and NMEC can cross the blood–brain barrier into the central nervous system, causing meningitis [18].

Contamination of surface waters with pathogenic strains of E. coli has been implicated in increasing number of disease outbreaks and deaths [19, 20] Disease outbreaks related to exposure to contaminated freshwaters are well documented [20–23]. The occurrence of pathogenic E. coli strains harbouring virulence genes (VGs) in environmental waters could be linked to contamination by storm events, faeces from domestic and wild animals as well as humans, runoffs from agricultural lands, sewage overflows, farm animals, pets and birds [11, 24–27]. However, only a few studies have investigated the presence of E. coli strains carrying VGs in environmental waters [28–34]. Exposure to recreational waters has been linked to high numbers (21 out of 31) of reported E. coli O157:H7 disease outbreaks in the United States from 1982 to 2002 [35]. Prevalence studies on the various E. coli pathotypes are important since it has been shown through various studies that the prevalence of diarrhoeagenic E. coli is region-specific [36]. Studies on the prevalence of DEC categories and their importance in diarrhoea have not been carried out extensively in Nigeria [37–41], with investigations on the southwestern axis being scantily documented on stool samples but not on environmental waters. A controlled study using the traditional culture/serology technique and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) was designed to ascertain the level and spectrum of bacterial pathogens and define the association of various categories of E. coli with diarrhoea in Enugu and Onitsha, Southeastern Nigeria [42]. To the best of our knowledge, no investigation on Escherichia coli pathotypes distribution has been carried out on the freshwater environments of Nigeria. Hence, in this paper, we report for the first time the prevalence and distribution of diarrhoeagenic E. coli pathotypes in surface waters in Osun State, South-Western Nigeria.

Results

E. coli confirmation

Of the 480 presumptive E. coli isolates recovered from the sampling sites, 410 were confirmed to be E. coli out of which 300 isolates made up of 30 from each sampling location were pooled together for further analysis. Figure 2 below shows the gel electrophoresis picture of the PCR products of the uidA gene amplification.

Map of Osun State Nigeria showing the locations of the sampling sites. Reprinted from [98] Sci Total Environ, 523, Titilawo Y., Obi L. and Okoh A., Antimicrobial resistance determinants of Escherichia coli isolates recovered from some rivers in Osun State, South-Western Nigeria: Implications for public health, 82–94, Copyright (2015), with permission from Elsevier

Prevalence of E. coli in the river samples

Confirmed E. coli isolates in the river samples at all sites ranged between 34 CFU/100 ml at the R5 site and 76 CFU/100 ml at the R7 site (Fig. 3).

Prevalence of virulence genes (VGs) amongst confirmed E. coli isolates

Among the 300 confirmed E. coli isolates assessed for the various VGs, 273 (91 %) harboured at least 1 VG while 27 (9 %) isolates harboured none. Overall, 91 % of the isolates were found to harbour between 1 and 4 VGs (Fig. 4). The modal occurrence of 1 VG was recorded at site R2 with 50 (33 %) of the isolates being positive for 1 VG each. The prevalence of multiple VGs in the E. coli isolates was equally higher at R2 than at other sites. The heat-labile toxin, lt gene was the most commonly detected gene at site R1 in 24 (80 %) of the isolates, followed by the adhesion papC gene, detected in 17 (57 %) of the isolates (Fig. 4). Similarly, the modal occurrence of 2 VGs was at R2 in 12 (10 %) isolates. None of the isolates from R6, R7 and R10 sites harboured 2 VGs Also, the modal prevalence of 3 VGs and 4 VGs were at R3 and R2 each in 2 (7 %) (Fig. 4). The invasion plasmid antigen gene, ipaH was not observed throughout the study and was therefore omitted from subsequent analysis. The representative gel electrophoresis profiles of amplified products of the investigated diarrhoeagenic and non-diarrhoeagenic coding genes are shown in Fig. 5.

A representative gel electrophoresis profile of different virulence genes of the diarrhoeagenic and non-diarrhoeagenic E. coli isolates. Lane 1: molecular weight marker (Thermo Scientific 100 bp DNA ladder), lane 2: negative control, lane 3: lt, lane 4: eagg, lane 5: eae, lane 6: stx1, lane 7: stx2 and lane 8: daaE

Statistical analysis using one-way ANOVA was performed on the pooled data in order to further explore the distribution of the remaining 9 VGs among all the ten sites. There was a significantly higher occurrence (P < 0.05) of 1 VG at sites R4, R5, R7 and R8 than at any other sites. While sites R1 and R2 were not significantly different in the prevalence of 2 VGs in their isolates (P > 0.05), a significant difference was observed when compared to the other 8 sites tested (P < 0.05). Similarly, the differences in the occurrences of 3 VGs among sites R1, R2, R6, R7 and R8 were not significant (P > 0.05).

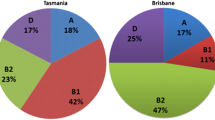

Comparative prevalence of E. coli pathotypes

To identify the prevalence of different pathotypes of E. coli isolates in all the ten sites, VGs were grouped according to their association with different E. coli pathotypes. The percentage site-specific distribution of the E. coli pathotypes in the ten sampling locations is shown in Fig. 6. Overall, isolates belonging to the intestinal ETEC pathotype were the most commonly detected (45 %), followed by the extra-intestinal UPEC (19 %) and the lowest was EAEC (2 %). Approximately, 21, 18 and 12 % of the E. coli isolates in sites R3, R5 and R8 could be placed into five main pathotypes with EPEC, ETEC, EHEC, UPEC and NMEC mostly observed. While EAEC was noticed at sites R3 and R5, DAEC was detected at R8. Similarly, the ETEC pathotype was commonly found associated with UPEC (20 %) at sites R2 and R4 each, and 13 % at site R3, followed by ETEC/EHEC and ETEC/NMEC (10 %) each (Fig. 6).

In addition, the percentage distribution of pathotypes was uniform at almost all the sampled sites except R6, R7 and R10. Approximately, 3 % of E. coli isolates could be differentiated into more than three pathotypes and this was observed at sites R1, R2, R3, R6, R7 and R8 in the same proportion (3 %) each, with the ETEC/EPEC/UPEC pathotypes commonly found at R2 and R7. Conversely, 3 % of the isolates positive for multiple VGs could only be grouped into four defined pathotypes as observed at sites R2 and R4 only, with ETEC/EPEC/EHEC/EAEC common to both (Fig. 6). Other sampling sites’ isolates did not carry multiple VGs sufficient enough to be categorized into four pathotypes.

Comparison of E. coli VG profiles from ten sites

VGs were further classified into toxin, adhesion and invasion genes based on functional characteristics of the genes (Table 2). This enabled us to identify the prevalence of different virulence genes of E. coli with observable differences in each site. A comparative analysis of the distribution of the 9 VGs observed across all the ten sites is presented in Fig. 7. In general, the highest frequency of VGs in E. coli isolates was obtained at site R2 (16 %), followed by site R1 (15 %) and the lowest at site R10 (2 %). Overall, the highest occurrences of VGs were observed at R1 and R3, with 7 VGs each and the lowest at site R10 with 3 VGs. The VGs papC and lt were the most frequently detected across all the sites, whereas the bfp, eagg, stx2 and ibeA genes were infrequently detected (Fig. 7). Among the toxin genes screened in this study, lt was the most prevalent gene at all sites (45 %) except at site R9 where it was not detected. Likewise, papC was the most commonly detected adhesion gene observed across all the sampling sites (19 %) with eagg gene being the least (2 %). Conversely, of the two invasion genes assessed, ibeA was detected at a very low prevalence (3 %) while ipaH was not detected in all the isolates (0 %) (Fig. 7).

A comparison between the sites was made (ANOVA) to determine if the sites were similar or different on the basis of occurrence of VGs. Both the sites R1 and R2 were significantly different (P < 0.05) in the occurrence of stx1 toxin and eae adhesion genes compared to other sites, whereas the difference between the occurrence of stx2 toxin gene in the E. coli isolates from site R2 was found to be statistically non-significant (P > 0.05) in relation to those from the other sites except site R1. Similarly, there was a significant difference in the occurrence of ibeA invasion gene among the isolates obtained at sites R5 and R9 (P < 0.05).

Discussion

The present study investigated the distribution and frequency of defined pathotypes of E. coli isolates in river water samples from Osun State, South-western Nigeria. Generally, the mean annual counts of the presumptive E. coli obtained in all the sampling sites were relatively high. E. coli has been used extensively as one of the major faecal indicator bacteria due to the previous notion that it has limited survival ability in the environment though recent studies have suggested that some pedigrees of E. coli have adapted and acclimatized within tropical, subtropical and even temperate regions [43, 44], and as such could be the germane reason for E. coli to flourish especially within freshwaters. In this study, sites R1, R2, R4, R6 and R7 with higher counts of E. coli were those located in pasture and peri-urban catchments with multiple sources of faecal pollution such as run-offs and dungs from cattle, horses and wild animals. There is a high likelihood that the isolates were mainly from human and animal excreta because during our sampling periods, human and animal excreta were sighted at the banks of the rivers, livestock were seen drinking water from the rivers, farmers and bricklayer were bathing and used waters from the car washing centers drained into the river. This further implicates both humans and animals as potential sources for the recovered E. coli pathovars. A previous study has also reported the presence of high numbers of faecal indicator bacteria originating from defective septic systems and grazing animals in freshwater sites and surface waters of developing countries [45, 46]. Other likely sources include mobilization of E. coli persisting in the soil [47], sediments [48] and aquatics [49].

In our study, VGs were detected in the E. coli isolates suggesting the presence of pathogenic E. coli strains in these waters. Otherwise, this may indicate an incessant input of these bacteria from a common source in the water or a combination of both. Generally, the results illustrate varied occurrence of diarrhoeagenic and non-diarrhoeagenic E. coli pathotypes with (91 %) of the isolates grouped under seven main E. coli pathotypes.

A large number of the E. coli isolates tested positive for toxin genes. The VG lt associated with ETEC strains was the most prevalent of all (45 %). This finding is worriedsome, considering the fact that it is the most common agent of traveler’s diarrhoea with food and water implicated as the modes of transmission [50, 51]. The presence of ST and/or LT enterotoxins which are commonly associated with ETEC strains have been reported by other workers in surface waters [52, 53], and are thought to originate from swine and humans with diarrhoea. ETEC strains are the most frequently isolated bacterial enteric pathogens in children below 5 years of age in developing countries and responsible for approximately 300 million diarrhoea cases and 380 000 deaths annually [54, 55], and their prevalence in surface water sources in developing countries has been documented [56]. The pathotype has been predominant followed by EPEC, EAEC and STEC in developing countries [57].

EHEC causes haemorrhagic colitis and haemolytic uremic syndrome in humans, and the key virulence factors include intimin (eae gene) and shiga toxins (stx1 and stx2 genes) [58]. Though, none of the isolates harboured a combination of the shiga toxin genes, nonetheless the relatively high occurrence of the stx1 gene (6 %) compared to stx2 (1 %) in the water E. coli isolates suggests the capability of each gene in causing acute diarrhoea in humans. This observation contradicts the relatively high occurrence of the stx2 gene (10 %) compared to stx1 (6 %) in the storm water E. coli isolates, which suggests that E. coli carrying a combination of the EHEC genes, are known to cause more severe diarrhoea in humans [15]. The most prevalent pathotypes of E. coli responsible for diarrhoeal diseases include enterohaemorrhagic or shiga toxin producing E. coli (EHEC or STEC) and enterotoxigenic E. coli (ETEC) [9]. The contamination of drinking or recreational waters with such E. coli pathotypes has been linked to waterborne disease outbreaks and mortality [53, 59].

EPEC has been shown to be a major cause of diarrhoea in young children [6]. The eae gene, which codes for intimin protein, was the fourth most prevalent gene in this study (6 %). This gene is necessary for intimate attachment to host epithelial cells in both the EHEC and EPEC pathotypes. Our findings tend to strongly disagree with the previous finding of significantly higher prevalence of the eae gene (up to 96 %) in surface water reported in other studies [22, 60]. Typical EPEC strains carry the LEE pathogenicity island, which encodes for several virulence factors, including intimin (eae) and the plasmid-encoded bundle forming pilus (bfp), which mediates adhesion to intestinal epithelial cells [34]. Therefore, all the E. coli isolates were further screened for the presence of the eae and bfp genes to determine their association with the EPEC pathotype. In this study, a noticeably low prevalence of the bfp gene (4 %) was detected, suggesting that prevalence of the EPEC-like pathotype could be expected in the surface water bodies. In addition, eae was also detected in 4 % isolates which lacked other typical genes from both EPEC group. This indicates prevalence of this gene in E. coli isolated from the freshwater environments. This finding is of great concern, as an atypical EPEC pathotype which lacks the bfp gene but carries the eae gene has been found to be a major cause of gastroenteritis worldwide [61], in patients suffering from community-acquired gastroenteritis in Melbourne, Australia [62], and from children with diarrhoea in Germany [63]. Approximately 2 % of the isolates carried both eae and bfp genes suggesting the presence of typical EPEC pathotype. The relatively low occurrence of the combination of both atypical EPEC genes in the water E. coli isolates is alarming due its possible significance in the cause of severe diarrhoea in humans. However, the role of atypical EPEC in diarrhoea has not been established assertively [9, 10, 64], and this study did not aim at revealing the diarrhoeagenic role of this pathotype.

In addition to the most prevalent ETEC strains obtained, EPEC and EHEC were the second- and third-more-common diarrhoeagenic pathotypes detected in this study respectively, with each group represented by 10 and 7 % isolates respectively. This is a strong indication that the three pathotypes occur widely in the surface water samples. The presence of E. coli strains with virulence characteristics similar to EPEC, ETEC and EHEC in fresh and estuarine waters have been previously reported [29, 30]. Generally, a few EHEC-like strains identified in this study were in agreement with other studies executed in different parts of the world [65, 66], and a low prevalence of EHEC infection has been observed in developing countries [67, 68].

EAEC is an emerging pathogen associated with diarrhoea. It has been identified in travelers, children in the developing world and human immunodeficiency virus infected patients with diarrhoea [9, 66, 69–71]. In the present study, among the DEC types, eagg gene of EAEC strains was the least frequently isolated adhesion VG with only 7 (2 %) strains detected in all the isolates, yet the pathotype has been an important diarrhoeagenic pathogen with its characteristic persistent diarrhoea in children and adults. This finding seems to be inconsistent with the previously reported high prevalence of the EAEC pathotype in fresh and estuarine water samples [60], but tends to align with the earlier observation of a less common DAEC, EAEC and a variety of different EHEC and EPEC pathotypes with the exception of enteroinvasive E. coli which was not detected in the 509 samples studied [72, 73]. Several studies have reported that contaminated food and water hygiene are the main vehicles of transmission with EAEC [50]. Similar findings have been described [74] and elsewhere [52, 75]. Our observation on the occurrences of ETEC, EPEC, EAEC and NMEC-like strains concurs with the report that ETEC is the most prevalent pathotype detected, followed by low prevalence of EPEC and NMEC, and absence of EIEC pathotypes in E coli isolates of surface water [76].

Uropathogenic E. coli (UPEC) and neonatal meningitis E. coli (NMEC) are the two other extra-intestinal E. coli (ExPEC) pathotypes that have been characterized [77, 78]. The study shows a higher prevalence of VG papC (19 %), associating with UPEC pathotype than the NMEC VG ibeA (3 %). The presence of E. coli strains with virulence characteristics similar to ExPEC have been reported previously in the fresh and estuarine waters [31]. This observation was of interest and may be an indication of a high potential health risk of such waters as the number of ExPEC VG(s) in E. coli has been suggested to be proportional to its pathogenic potential [79].

Overall, the detection of most of the VGs tested was relatively low aside from lt and papC, ranging from 1 to 7 %. This finding correlates with the reports of [28–30], that the prevalence of E. coli isolates harbouring VGs in environmental waters is low ranging from 0.9 to 10 %. In the light of this, screening of a large number of isolates for possible detection of VGs is advocated. E. coli isolates have been concentrated from large volume (1 L) of water samples followed by an enrichment step to increase PCR detection sensitivity [80–82].

The presence of a single or multiple VGs in an E. coli strain does not necessarily indicate that a strain is pathogenic unless that strain has the appropriate combination of VGs to cause disease in the host [59, 83]. The pathogenic E. coli strains use a complex multistep mechanism of pathogenesis involving a number of virulence factors depending upon the pathotype, which consists of attachment, host cell surface modification, invasin, a variety of toxins and secretion systems which eventually lead toxins to the target host cells [9]. Thus, VGs are appropriate targets for determining the pathogenic potential of a given E. coli isolate [6]. The occurrence of unusual combinations of VGs in E. coli isolates observed in this study could be explained on the basis of horizontal gene transfer between cells, which enables the exchange of genetic material located on mobile elements (transposons, integrons or plasmids) among related or unrelated bacterial species [84]. Further screening of the E. coli isolates with these unusual VG patterns in tissue culture or animal models would be required to demonstrate their pathogenicity.

In this study, we collected water samples from communities with diverse human population densities and land uses to determine if these factors influence the distribution of VGs (Fig. 7). The results of this study show a relatively low and clear pattern of occurrence of VGs across the sites with a noticeable difference of occurrence of 4 VGs and 3 VGs at sites R9 and R10 respectively. Overall, it was evident that the point and non-point sources of contamination were potentially similar across the sampling sites in their characteristic features. Similarly, all the sampling sites are bordered by farm animals such as ruminants which are known to be potential sources of these VGs [11, 14, 32, 85]. Animals, humans and the environments including water sources serve as natural habitats of virulent strains of E. coli [6, 10, 86–88]. Storm runoffs may also increase the prevalence of microbial pathogens, including diarrhoeagenic E. coli pathotypes in the surface water bodies due to transport of faecal contamination from land [25].

A better understanding of the prevalence and distribution of E. coli pathotypes in water sources used for potable, non-potable or recreation purposes could be an important tool in the development of public health risk mitigation strategies. Pathotyping of E. coli isolates may also provide useful information to identify potential sources of pollution, as the principal reservoirs of ETEC and EPEC pathotypes are majorly humans and ruminants, whereas the bovine intestinal tract is the main source of the EHEC pathotype [9, 13]. The lower prevalence of the EHEC pathotype compared to other pathotypes suggests that human faecal contamination of the waterways is the main source of diarrhoeagenic E. coli pathotypes in the surface water as opposed to contamination from animals. This stresses the importance of controlling sources of human faecal pollution such as municipal wastewater sources, sewage leaks and overflows, wastewater treatment plant discharge to reduce potential threats to human health. The results demonstrate that the risk of contracting infection, however, may increase over time if no appropriate preventive and controlling measures are ensured. Since this study aimed at detecting E. coli pathotypes carrying associated VGs, it is logically reasonable to assume that actual distribution of these VGs in surface water could be relatively higher. While the ability of E. coli isolates described in this study to cause human diarrhoeal diseases was not established, a high proportion of isolates carrying a full set of VGs have been linked to defined pathotypes. Further screening for other VGs along with serotype testing and other assays may offer further information on pathogenicity of these isolates.

Conclusions

Detection of Escherichia coli in river water in Osun State, South-western Nigeria, indicates faecal contamination and the possible presence of other enteric pathogens. The prevalence of virulence markers in E. coli isolates from river water sources is indicative of increased risks of mortality, especially among the vulnerable populations and immunocompromised individuals, should they contract infections through the use of river water for consumption or other household related purposes. It equally emphasizes the importance of safe water supply, good hygiene and sanitation practices both in rural and urban communities. Finally, this study has revealed a number of E. coli isolates positive for single and multiple VGs which indicates the presence of potential pathogenic E. coli in these waters and it clearly highlights the need to develop a better understanding of public health implications of occurrence of E. coli carrying VGs in surface waters used for potable, non-potable and recreational purposes.

Methods

Description of study area and collection of water samples

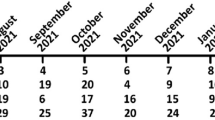

The ten river water sources used in this study are located in Osun State, Southwestern Nigeria. The state is an inland state with its headquarters located in Osogbo. It is bounded in the north by Kwara state, south by Ogun state, west by Oyo state and east partly by Ekiti and Ondo states. The sampling locations were coded as follows: R1: Erinle-Ede; R2: Ido-Osun; R3: Osun-Osogbo, R4: Oba-Iwo; R5: Ejigbo; R6: Ilobu-Okinni; R7: Asejire-Ikire; R8: Shasha; R9 and Ila-Oke Ila, R10: Inisha-Okuku (Fig. 1).

Water samples were collected at each site in clean, sterile 2.5 L bottles between September 2011 and August 2012 from ten sampling locations, transported to the laboratory on ice and processed within 6 h of collection. Table 1 shows the site code, location, land use and potential sources of faecal pollution of each sampling site.

Isolation of presumptive of Escherichia coli

The standard membrane filtration method was used for the processing and quantification of presumptive E. coli in the water samples [89]. A volume of 100 ml of each water sample was filtered through 0.45 mm pore size nitrocellulose membrane filters (Millipore, Ireland). The filters were placed on eosin methylene blue agar (Oxoid, England), incubated overnight at 44.5 °C for characteristic green metallic sheen colonies and thereafter counted. The isolates were further purified on E. coli chromogenic agar (Conda Pronadisa, Spain), incubated at 37 °C overnight and individual well-isolated typical E. coli colonies were selected and transferred onto nutrient agar slants for further studies. A total of 480 presumptive E. coli colonies were isolated during the 12-month sampling regime.

PCR confirmation of E. coli and extraction of DNA

The presumptive E. coli were confirmed by polymerase chain reaction using the housekeeping 4-methylumbelliferyl-glucuronide (uidA) gene marker as previously described [90], and the positive isolates were preserved at −80 °C in 20 % glycerol. E. coli ATCC 25922 (ATCC, USA) was used as a positive control. The bacterial genomic DNA was extracted using the boiling method as described elsewhere [91, 92], and the recovered DNA was used as template for amplification reactions.

PCR detection of virulence genes

Using a conventional singleplex PCR, confirmed E. coli isolates (n =300) were screened for the presence of 10 E. coli VGs for a number of adhesion, invasion and toxin determinants to correctly place them under the 8 pathotypes studied. The list of VGs, categorized on the basis of their functional characteristics and association with Escherichia coli pathotypes is shown in Table 2. The primers used for PCR detection of the VGs and other relevant characteristics are listed in Table 3. For each PCR experiment, appropriate positive and negative controls were included. The PCR amplification was performed using a thermocycler system (Bio-Rad Thermal cycler, USA). Each 25 μl PCR mixture contained 12.5 μl of PCR master mix (Thermo Scientific, (EU) Lithuania), 0.5 μl each of primer (Inqaba Biotech, SA), 5 μl of template DNA and 6.5 μl of PCR grade water. To detect the amplified product, 5 μl of amplicons was visualized by electrophoresis through a 1.8 % agarose gel (Merck, SA) at a voltage of 100 for 45 min in 0.5X TBE buffer and stained with ethidium bromide (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) using the gel documentation system (Alliance 4.7, France). Identification of the bands was established by comparison of the band sizes with molecular weight markers of 100-bp (Thermo Scientific, (EU) Lithuania). Samples were considered to be positive for a specific VG when the visible band was the same size as that of the positive control DNA. To minimize PCR contamination, DNA extraction, PCR set up, and gel electrophoresis were performed in isolated rooms. The positive controls were sourced from DSMZ Germany and included: DSM 10819 for NMEC; DSM 4819 for UPEC; DSM 8695 for EPEC; DSM 10973 for ETEC; DSM 10974 for EAEC; and DSM 10975 for EIEC except ATCC 35150 for EHEC from USA. There was no positive control available for DAEC but we went further to optimize the PCR condition of the related gene for possible detection of the expected amplicon band size.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using IBM Statistical Package for Social Sciences [(SPSS) Version 20 software]. Data on E. coli mean counts for each site were recorded in 100 ml per CFU. The one way analysis of variance (ANOVA) was performed to investigate the existence of any correlation between E. coli counts, the difference in VG distribution and the degree of correlation between the number of E. coli isolates and the number of VGs observed with respect to each site. Correlations and test of significance were considered statistically significant when P values were < 0.05.

Abbreviations

- ANOVA:

-

Analysis of Variance

- APEC:

-

Avian Pathogenic Escherichia coli

- ATCC:

-

American Type Culture Collection

- CDEC:

-

Cell-Detaching Escherichia coli

- CFU:

-

Colony Forming Unit

- DAEC:

-

Diffusely Adherent Escherichia coli

- DEC:

-

Diarrhoeagenic Escherichia coli

- DNA:

-

Deoxyribonucleic Acid

- EAEC:

-

Enteroaggregative Escherichia coli

- EHEC:

-

Enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli

- EIEC:

-

Enteroinvasive Escherichia coli

- EPEC:

-

Enteropathogenic Escherichia coli

- ETEC:

-

Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli

- ExPEC:

-

Extra-Intestinal Pathogenic Escherichia coli

- InPEC:

-

Intestinal Pathogenic Escherichia coli

- NMEC:

-

Neonatal Meningitis Escherichia coli

- PCR:

-

Polymerase Chain Reaction

- R:

-

River

- SAMRC:

-

South African Medical Research Council

- SPSS:

-

Statistical Package for Social Sciences

- UPEC:

-

Uropathogenic Escherichia coli

- VG:

-

Virulence Gene

- WRC:

-

Water Research Commission

References

Sarantuya JJ, Nishi J, Wakimoto N, Erdene S, Nataro JP, Sheikh J, et al. Typical enteroaggregative Escherichia coli is the most prevalent pathotype among E. coli strains causing diarrhea in Mongolian children. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:133–9.

Clarke SC. Diarrheagenic Escherichia coli – an emerging problem? Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2001;41:93–8.

Elias WP, Czeczulin JR, Henderson IR, Trabulsi LR, Nataro JP. Organization of biogenesis genes for aggregative adherence fimbria II defines a virulence gene cluster in enteroaggregative Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1999;181:1779–85.

NHMRC. The guidelines for managing risks in recreational water. Canberra, Australia: NHMRC Publications; 2008. www.nhmrc.gov.au/files_nhmrc/publications/attachments/eh38.pdf. Accessed 17 Jun 2014.

USEPA. Ambient water quality criteria for bacteria EPA-440/5-84-002. Washington, DC: U.S. Environmental Protection Agency; 1986.

Kuhnert P, Boerlin P, Frey J. Target genes of virulence assessment of Escherichia coli isolates from water, food and the environment. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2000;24:107–17.

Galane PM, Le Roux M. Molecular epidemiology of Escherichia coli isolated from young South African children with diarrhoeal diseases. J Health Popul Nutr. 2001;19:31–7.

Russo TA, Johnson JR. Proposal for a new inclusive designation for extraintestinal pathogenic isolates of Escherichia coli: ExPEC. J Infect Dis. 2000;181:1753–4.

Kaper JB, Nataro JP, Mobley HL. Pathogenic Escherichia coli. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2004;2:123–40.

Nataro JP, Kaper JB. Diarrhoeagenic Escherichia coli. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1998;11:142–201.

Ishii S, Meyer KP, Sadowsky MJ. Relationship between phylogenetic groups genotypic clusters and virulence genes profiles of Escherichia coli strains from diverse human and animal sources. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73:5703–10.

Abduch-Fabrega VL, Piantino-Ferreir AJ, Reis da Silva-Patricio F, Brinkley C, Affonso-Scaletsk IC. Cell-detaching Escherichia coli (CDEC) strains from children with diarrhoea: identification of a protein with toxigenic activity. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2002;217:191–7.

Levine MM. Escherichia coli that cause diarrhea: enterotoxigenic, enteropathogenic, enteroinvasive, enterohemorrhagic, and enteroadherent. J Infect Dis. 1987;155:377–89.

Djordjevic S, Ramachandaran V, Bettelheim KA, Vanselow BA, Holst P, Bailey G, et al. Serotypes and virulence gene profiles of shiga-toxin producing Escherichia coli strains isolated from feces of pasture-fed and lot-fed sheep. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2004;70:3910–7.

Paton AW, Paton C. Detection and characterization of Shiga toxigenic Escherichia coli by using multiplex PCR assays for stx1, stx2, eaeA, enterohemorrhagic E. coli hlyA, rfbO111 and rfbO157. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:598–602.

Johnson JR, Stell AL. Extended virulence genotypes of Escherichia coli strains from patients with urosepsis in relation to phylogeny and host compromise. J Infect Dis. 2000;181:261–72.

Jallat C, Livrelli V, Darfeuille-Michaud A, Rich C, Joly B. Escherichia coli strains involved in diarrhea in France: high prevalence and heterogeneity of diffuse adhering strains. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:2031–7.

Croxen MA, Finlay BB. Molecular mechanisms of Escherichia coli pathogenicity. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2010;8:26–38.

Feldman KA, Mohle-Boetani JC, Ward J, Furst K, Abbott SL, Ferrero D, et al. A cluster of Escherichia coli O157: non-motile infections associated with recreational exposure to lake water. Public Health Rep. 2002;117:380–5.

Olsen SJ, Miller G, Breuer T, Kennedy M, Higgins C, Walford J, et al. A waterborne outbreak of Escherichia coli O157:H7infections and haemolytic uremic syndrome: implications for rural water systems. Emerg Infect Dis. 2002;8:370–5.

Ackman D, Marks S, Mack P, Caldwell M, Root T, Birkhead G. Swimming associated haemorrhagic colitis due to Escherichia coli O157:H7 infection: evidence of prolonged contamination of a fresh water lake. Epidemiol Infect. 1997;119:1–8.

Shelton DR, Karns JS, Higgins JA, Van Kessel JA, Perdue ML, Belt KT, et al. Impact of microbial diversity on rapid detection of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli in surface waters. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2006;261:95–101.

Chalmers RM, Aird H, Bolton FJ. Waterborne Escherichia coli O157. Symp Ser Soc Appl Microbiol. 2000;29:124–32.

Parker JK, McIntyre D, Noble RT. Characterizing faecal contamination in storm-water runoff in coastal North Carolina, U.S.A. Water Res. 2010;44:4186–96.

Sidhu JP, Hodgers L, Ahmed W, Chong MN, Toze S. Prevalence of human pathogens and indicators in storm-water runoff in Brisbane, Australia. Water Res. 2012;46:6652–60.

Brownell MJ, Harwood VJ, Kurz RC, McQuaig SM, Lukasik J, Scott TM. Confirmation of putative storm water impact on water quality at a Florida beach by microbial source tracking methods and structure of indicator organism populations. Water Res. 2007;41:3747–57.

Sauer EP, Vandewalle JL, Bootsma MJ, McLellan SL. Detection of the human specific Bacteroides genetic marker provides evidence of widespread sewage contamination of storm water in the urban environment. Water Res. 2011;45:4081–91.

Martins MT, River IG, Clark DL, Olson BH. Detection of virulence factors inculturable Escherichia coli isolates from water samples by DNA probes and recovery of toxin-bearing strains in o-nitrophenol-b-D-galactopyranoside-4methylumbelliferyl-b-D-glucuronide media. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992;58:3095–100.

Lauber CL, Glatzer L, Sinsabaug RL. Prevalence of pathogenic Escherichia coli in recreational waters. J Great Lakes Res. 2003;29:301–6.

Chern EC, Tsai YL, Olson BH. Occurrence of genes associated with enterotoxigenic and enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli in agricultural waste lagoons. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2004;70:356–62.

Hamelin K, Bruan G, El-Shaarawi A, Hill S, Edge TA, Bekal S, et al. A virulence and antimicrobial resistance DNA microarray detects a high frequency of virulence genes in Escherichia coli isolates from Great Lakes recreational waters. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2006;72:4200–6.

Ahmed W, Neller R, Katouli M. Evidence of septic system failure determined by a bacterial biochemical fingerprinting method. J Appl Microbiol. 2005;98:910–20.

Ram S, Vajpayee P, Shanker R. Prevalence of multi antimicrobial agent resistant shiga toxin and enterotoxin producing Escherichia coli in surface waters of river Ganga. Environ Sci Technol. 2007;41:7383–8.

Hamilton M, Hadi AZ, Griffith F, Sadowsky MJ. Large scale analysis of virulence genes in Escherichia coli strains isolated from Avalon bay,CA. Water Res. 2010;44:5463–73.

Rangel JM, Sparling PH, Crowe C, Griffin PM, Swerdlow DL. Epidemiology of Escherichia coli O157: H7 outbreaks, United States, 1982–2002. Emerg Infect Dis. 2005;11:603–9.

Samie A, Nkgau TF, Bessong PO, Obi CL, Dillingham R, Guerrant RL. Escherichia coli pathotypes among human immunodeficiency virus infected patients in the Limpopo Province. Afr J Microbiol Res. 2012;6:6022–30.

Akinyemi KO, Oyefolu AO, Opere B, Otunba-Payne VA, Oworu AO. Escherichia coli in patients with acute gastroenteritis in Lagos, Nigeria. East Afr Med J. 1998;75:512–5.

Okeke IN, Lamikanra A, Steinruck H, Kaper JB. Characterization of Escherichia coli strains from cases of childhood diarrhoea in provincial southwestern Nigeria. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:7–12.

Okeke IN, Lamikanra A, Czeczulin J, Dubovsky F, Kaper JB, Nataro JP. Heterogeneous virulence of enteroaggregative Escherichia coli strains isolated from children in Southwest Nigeria. J Infect Dis. 2000;181:252–60.

Okeke IN, Steinrück H, Kanack KJ, Elliott SJ, Sundström L, Kaper JB, et al. Antibiotic-resistant cell-detaching Escherichia coli strains from Nigerian children. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40:301–5.

Okeke IN, Oladipupo O, Lamikanra A, Kaper JB. Etiology of acute diarrhoea in adults in Southwestern Nigeria. J Clin Microbiol. 2003;41:4525–30.

Nweze EI. Virulence properties of diarrhoeagenic E. coli and etiology of diarrhoea in infants, young children and other age groups in Southeast, Nigeria. Am Eur J Sci Res. 2009;4:173–9.

APHA. Standard methods for the examination of water and wastewater. 19th ed. Washington DC: APHA; 1998.

Tsai LY, Palmer CL, Sangeermano LR. Detection of Escherichia coli in sludge by PCR. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1993;5:353–7.

Frahm E, Obst U. Application of the fluorogenic probe technique (TaqMan PCR) to the detection of Enterococcus spp. and Escherichia coli in water samples. J Microbiol Methods. 2003;52:123–31.

Juhna T, Birzniece P, Larsson S, Zulenkovs D, Shapiro A, Azeredo NF, et al. Detection of Escherichia coli in biofilm from pipe samples and coupons in drinking water distribution networks. J Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73:7456–64.

Stacy-Phipps S, Mecca JJ, Weiss JB. Multiplex PCR assay and simple preparation method for stool specimens detect enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli DNA during the course of infection. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:1054–9.

Lopez-Saucedo C, Cerna JF, Villegas-Sepulveda N, Thompson R, Velazquez FR, Torres J, et al. Single multiplex polymerase chain reaction to detect diverse loci associated with diarrheagenic Escherichia coli. Emerg Infect Dis. 2003;9:127–31.

Kong RYC, Lee SKY, Law TWF, Law SHW, Wu RSS. Rapid detection of six types of bacterial pathogens in marine waters by multiplex PCR. Water Res. 2002;36:2802–12.

Vidal M, Kruger E, Duram C, Lagos R, Levine M, Prado V, et al. Single multiplex PCR assay to identify simultaneously the six categories of diarrhoeagenic Escherichia coli associated with enteric infections. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:5362–5.

Cebula TA, Payne WL, Feng P. Simultaneous identification of strains of Escherichia coli serotype 0157:H7 and their shiga-like toxin type by mismatch amplification mutation assay-multiple PCR. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:248–50.

Le Bouguenec C, Archambaud B, Labigne A. Rapid and specific detection of the pup, ufa and sfa adhesin-encoding operons in uropathogenic Escherichia coli strains by polymerase chain reaction. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:1189–93.

Ishii S, Sadowsky MJ. Escherichia coli in the environment: implications for water quality and human health. Microbes Environ. 2008;23:101–8.

Walk ST, Alm EW, Clahoun LM, Mladonicky JM, Whittam TM. Genetic diversity and population structure of Escherichia coli isolated from freshwater beaches. Environ Microbiol. 2007;9:2274–88.

Ahmed W, Neller R, Katouli M. Host species-specific metabolic fingerprint database for enterococci and Escherichia coli and its application to identify sources of faecal contamination in surface waters. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005;71:4461–8.

Brennan F, Abram F, Chinalia F, Richards K, O’Flaherty V. Characterization of environmentally E. coli isolates leached from Irish soil. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2010;76:2175–80.

Czajkowska D, Witkowska-Gwiazdowska A, Sikorska I, Boszczyk-Maleszak H, Horoch M. Survival of Escherichia coli serotype O157:H7. Pol J Environ Stud. 2005;14:423–30.

Lothigius A, Sjoling A, Svennerholm AM, Bolin I. Survival and gene expression of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli during long-term incubation in sea water and freshwater. J Appl Microbiol. 2010;108:1441–9.

Huang DB, Mohanty A, DuPont HL, Okhuysen PC, Chiang T. A review of an emerging enteric pathogen: enteroaggregative Escherichia coli. J Med Microbiol. 2006;5:1303–11.

Mohamed JA, Huang DB, Jiang ZD, DuPont HL, Nataro JP, Belkind-Gerson J, et al. Association of putative enteroaggregative Escherichia coli virulence genes and biofilm production in isolates from travelers to developing countries. J Clin Microbiol. 2007;45:121–6.

Obi CL, Green E, Bessong PO, De-Villiers B, Hoosen AA, Igumbor EO, et al. Gene encoding virulence markers among Escherichia coli isolates from diarrhoeic stool samples and river sources in rural Venda communities of South Africa. Water SA. 2004;30:37–42.

Begum YA, Talukder KA, Nair GB, Qadri F, Sack RB, Svennerholm AM. Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli isolated from surface water in urban and rural areas of Bangladesh. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:3582–3.

Wennerås C, Erling V. Prevalence of enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli-associated diarrhoea and carrier state in the developing world. J Health Popul Nutr. 2004;22:370–82.

Steffen R, Castelli F, Hans Nothdurft D, Rombo L, Jane Zuckerman N. Vaccination against enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli, a cause of travelers’ diarrhea. J Travel Med. 2005;12:102–7.

Kass R. Traveller’s diarrhoea. Aust Fam Physician. 2005;34:243–5.

Qadri F, Svennerholm AM, Faruque AS, Sack RB. Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli in developing countries: epidemiology, microbiology, clinical features, treatment and prevention. J Clin Microbiol Rev. 2005;18:465–83.

Boerlin P, McEwen SA, Boerlin-Petzold F, Wilson JB, Johnson RP, Gyles CL. Associations between virulence factors of Shiga toxin producing Escherichia coli and disease in humans. J Clin Microbiol. 1999;37:497–503.

Bruneau A, Rodrigue H, Ismäel J, Dion R, Allard R. Outbreak of E. coli O157:H7 associated with bathing at a public beach in the Montreal-Centre region. Can Commun Dis Rep. 2004;30:133–6.

Masters N, Wiegand A, Ahmed W, Katouli M. Escherichia coli virulence genes profile of surface waters as an indicator of water quality. Water Res. 2011;45:6321–33.

Hernandes RT, Elias WP, Vieira MA, Gomes TA. An overview of atypical enteropathogenic Escherichia coli. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2009;297:137–49.

Robins-Browne RM, Bordun AM, Tauschek M, Bennett-Wood VR, Russell J, Oppedisano F, et al. Escherichia coli and community-acquired gastroenteritis, Melbourne, Australia. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10:1797–805.

Kozub-Witkowski E, Krause G, Frankel G, Kramer D, Appel B, Beutin L. Serotypes and virutypes of enteropathogenic and enterohaemorrhagic Escherichia coli strains from stool samples of children with diarrhoea in Germany. J Appl Microbiol. 2008;104:403–10.

Nataro JP, Mai V, Johnson J, Blackwelder WC, Heimer R, Tirrell S, et al. Diarrheagenic Escherichia coli infection in Baltimore, Maryland, and New Haven, Connecticut. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;43:402–7.

Gomes TA, Rassi V, MacDonald KL, Ramos SR, Trabulsi LR, Vieira MA, et al. Enteropathogens associated with acute diarrheal disease in urban infants in Sao Paulo, Brazil. J Infect Dis. 1991;164:331–7.

Nguyen TV, Le Van P, Le Huy C, Gia KN, Weintraub A. Detection and characterization of diarrhoeagenic Escherichia coli from young children in Hanoi, Vietnam. J Clin Microbiol. 2005;43:755–60.

Brown JE, Echeverria P, Taylor DN, Seriwatana J, Vanapruks V, Lexomboon U, et al. Determination by DNA hybridization of Shiga-like-toxin-producing Escherichia coli in children with diarrhea in Thailand. J Clin Microbiol. 1989;27:291–4.

Strockbine NA, Faruque SM, Kay BA, Haider K, Alam K, Alam AN, et al. Wachsmuth IK DNA probe analysis of diarrhoeagenic Escherichia coli: detection of EAF-positive isolates of traditional enteropathogenic E. coli serotypes among Bangladeshi paediatric diarrhoea patients. Mol Cell Probes. 1992;6:93–9.

Adachi JA, Ericsson CD, Jiang ZD, DuPont MW, Pallegar SR, DuPont HL. Natural history of enteroaggregative and enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli infection among US travelers to Guadalajara, Mexico. J Infect Dis. 2002;185:1681–3.

Keskimaki M, Mattila L, Peltola H, Siitonen A. Prevalence of diarrheagenic Escherichia coli in Finns with or without diarrhoea during a round-the-world trip. J Clin Microbiol. 2000;38:4425–9.

Nishikawa Y, Zhou Z, Hase A, Ogasawara J, Kitase T, Abe N, et al. Diarrheagenic Escherichia coli isolated from stools of sporadic cases of diarrheal illness in Osaka City, Japan between 1997 and 2000: prevalence of enteroaggregative E. coli heat-stable enterotoxin 1 gene-possessing E. coli. Jpn J Infect Dis. 2002;55:183–90.

Vidal R, Vidal M, Lagos R, Levine M, Prado V. Multiplex PCR for diagnosis of enteric infections associated with diarrhoeagenic Escherichia coli. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:1787–9.

Samie A, Obi CL, Dillingham R, Pinkerton RC, Guerrant RL. Enteroaggregative Escherichia coli in Venda, South Africa: distribution of virulence-related genes by multiplex polymerase chain reaction in stool samples of Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV)-positive and HIV-negative individuals and primary school children. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2007;77:142–50.

Gassama-Sow SPC, Gueye M, Gueye N, Perret JL, Mboup S, Aidara-Kanel A. Characterisation of pathogenic E. coli in Human Immunodeficiency Virus-related diarrhoea in Senegal. J Infect Dis. 2004;189:75–8.

Nolonwabo N, Timothy S, Elvis N, Anthony IO. Prevalence and antibiogram profiling of Escherichia coli pathotypes isolated from the Kat River and the Fort Beaufort abstraction water. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2014;11:8213–27.

Wiles TJ, Kulesus RR, Mulvey MA. Origins and virulence mechanisms of uropathogenic Escherichia coli. Exp Mol Pathol. 2008;85:11–9.

Dubois D, Prasadarao NV, Mittal R, Bret L, Roujou-Gris M. Bonnet R CTX-M β-Lactamase production and virulence of Escherichia coli K1. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15:1988–90.

Picard B, Garcia J, Gouriou S, Duriez P, Brahimi N, Bingen E, et al. The link between phylogeny and virulence in Escherichia coli extraintestinal infection. Infect Immun. 1999;67:546–53.

Ahmed W, Sawant S, Huygens F, Goonetilleke A, Gardener T. Prevalence and occurrence of zoonotic bacterial pathogens in surface waters determined by quantitative PCR. Water Res. 2009;43:4919–28.

Savichtcheva O, Okayama N, Okabe S. Relationships between Bacteroides 16S rRNA genetic markers and presence of bacterial enteric pathogens and conventional fecal indicators. Water Res. 2007;41:3615–28.

Scott TM, Jenkins TM, Lukasik J, Rose JB. Potential use of a host associated molecular marker in Enterococcus faecium as an index of human fecal pollution. Environ Sci Technol. 2005;39:283–7.

Gilmore MS, Ferretti JJ. The thin line between gut commensal and pathogen. Sci. 2003;299:1999–2002.

Davison J. Genetic exchange between bacteria in the environment. Plasmid. 1999;42:73–91.

Ahmed W, Tucker J, Bettelheim K, Neller R, Katouli M. Detection of virulence genes in Escherichia coli of an existing metabolic fingerprint database to predict the sources of pathogenic E. coli in surface waters. Water Res. 2007;41:3785–91.

Gyles CL. Shigatoxin-producing Escherichia coli: an overview. J Anim Sci. 2007;85:45–62.

Dupont HL. Diarrhoeal diseases in the developing world. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 1995;9:313–24.

Griffin PM. Escherichia coli O157:H7 and other enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli. In: Blaser MJ, Smith PD, Ravdin JI, Greenberg HB, Guerrant RL, editors. Infect Gast Tract. New York: Raven; 1999. p. 739–61.

Stephan R, Schumacher S. Resistance patterns of non-O157 Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC) strains isolated from animals, food and asymptomatic human carriers in Switzerland. Lett Appl Microbiol. 2001;32:114–7.

Titilawo Y, Obi L, Okoh A. Antimicrobial resistance determinants of Escherichia coli isolates recovered from some rivers in Osun State, Southwestern Nigeria: implications for public health. Sci Total Environ. 2015;523:82–94.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Water Research Commission (WRC) of South Africa for the grant K5/2145 which aided access to facilities to complete this study and the South African Medical Research Council (SAMRC) initiative for support. Titilawo Yinka is equally grateful to the University of Fort Hare for the provision of doctoral bursary.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

TY collected the water samples, isolated the E. coli, contributed to the performing of the experiments, data and statistical analyses, and writing of the manuscripts. OL contributed to the designing and performing of the experiments, provided financial support and reviewed the manuscript. OA conceived and designed the experiment, provided financial support, contributed to the performing of the experiments, writing of the manuscripts and reviewed the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ information

Not applicable.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Titilawo, Y., Obi, L. & Okoh, A. Occurrence of virulence gene signatures associated with diarrhoeagenic and non-diarrhoeagenic pathovars of Escherichia coli isolates from some selected rivers in South-Western Nigeria. BMC Microbiol 15, 204 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12866-015-0540-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12866-015-0540-3