Abstract

Background

Human peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) are extensively used for research of immune cell functions, identification of biomarkers and development of diagnostics and therapeutics for human diseases, among others. The assumption that “old blood samples” are not appropriate for isolation of PBMCs for functional assays has been a dogma in the scientific community. However, partial data on the impact of time after phlebotomy on the quality and stability of human PBMCs preparations impairs the design of studies in which time-controlled blood sampling is challenging such as field studies involving multiple sampling centers/sites. In this study, we evaluated the effect of time after phlebotomy over a 24 h time course, on the stability of human blood leukocytes used for immunological analyses. Blood samples from eight healthy adult volunteers were obtained and divided into four aliquots, each of which was left in gentle agitation at room temperature (24 °C) for 2 h (control), 7 h, 12 h and 24 h post phlebotomy. All samples at each time point were independently processed for quantification of mononuclear cell subpopulations, cellular viability, gene expression and cytokine secretion.

Results

A 24 h time delay in blood sample processing did not affect the viability of PBMCs. However, a significantly lower frequency of CD3+ T cells (p < 0.05) and increased LPS-induced CXCL10 secretion were observed at 12 h post-phlebotomy. Alterations in TNFα, CCL8, CCR2 and CXCL10 gene expression were found as early as 7 h after blood sample procurement.

Conclusions

These data reveal previously unrecognized early time-points for sample processing control, and provide an assay-specific time reference for the design of studies that involve immunological analyses of human blood samples.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Human peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMCs) preparations, consisting primarily of lymphocytes (T cells, B cells and NK cells) and monocytes, are one of the most widely used samples in biomedical research. PBMCs are employed in a wide array of assays that range in complexity from simple cytotoxicity evaluations to sophisticated single cell functional and phenotypic immunological or molecular assays [1,2,3]. In vitro, phenotypic characterization and functional evaluation of human cells is one of the pillars for the development of clinically implementable diagnostic, prognostic and therapeutic tools [4,5,6,7,8,9]. Therefore, standardization and reproducibility of these assays is critical for their routine performance and the reliability of results.

PBMCs are obtained mainly by density gradient centrifugation, a technique described by Boyum in 1968 [10]. Several factors could influence the quality of PBMCs preparations, such as the conditions of sample collection [11] (type of anticoagulant used and blood collection rate), sample processing time [12], technique used to obtain the PBMCs (apheresis vs. density gradient centrifugation) [13], and finally their preservation [14, 15]. These factors influence cell viability and cell count, gene and protein expression (e.g. surface markers), responses to mitogenic stimuli [16], impact cell functions and ultimately create bias in the study results.

Clinical studies that involve the use of human blood samples for analysis of immunological cell functions require strategies to optimize and standardize pre-analytical processes to minimize the variability of the data, maximize reproducibility of the assays and ultimately assure quality of the generated data. These strategies involve standardization of 1) the sampling technique: defining the time of day for sample procurement, the use of, and type of anticoagulant, the blood volume to be obtained, etc.; 2) sample handling: defining whether blood samples will be maintained in agitation or resting and at what temperature prior to analysis; 3) transportation: establishing the method of transportation to be used throughout the study, and the time from sample procurement to sample processing; 4) sample processing: methods for cell isolation and purification; and 5) storage: defining the medium and long term storage temperature, the minimum and maximum storage time, storage medium, among others. Establishing these parameters is particularly challenging for multicentric studies, where samples need to be collected at different clinical sites, introducing variability in some aspects such as the time between sample procurement and processing.

Although there is a general assumption in the community that “old blood samples” (without a precise time definition for “old”) should not be used, there is no systematic data on the impact of time after phlebotomy on the stability of PBMCs from human blood samples. In this study, we aimed to systematically assess the effect of time, over a 24 h time frame after phlebotomy, on the stability of human PBMCs used for downstream immunological analyses.

Methods

Study design

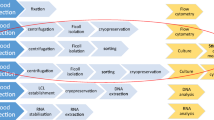

We evaluated the stability of human mononuclear cell populations in peripheral blood samples from eight healthy volunteers over a 24 h time frame after phlebotomy. Eligibility criteria included age between 18 and 60 years, no co-morbidities, no immunosuppressive conditions, no pregnancy or lactation and a negative human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) test. Blood samples (100 mL) were obtained by venipuncture of an arm vein, collected on 50 mL polypropylene tubes (Falcon, #352098), and anticoagulated with EDTA. Each sample was divided into four aliquots (25 mL) and left in gentle agitation using a Vari-Mix tube rocker at room temperature (24 °C) for 2 h (control), 7 h, 12 h and 24 h post phlebotomy (Fig. 1). Each 25 mL blood aliquote was independently processed for quantification of leukocyte subpopulations, isolation of mononuclear cells for assessment of viability, gene expression and functional analyses (in vitro cytokine production).

Schematic Workflow. Peripheral blood samples (100 mL) from 8 healthy donors were obtained by venipuncture and divided into four aliquots and left in gentle agitation at room temperature (24 °C) for 2 h (control), 7 h, 12 h (n = 5) and 24 h post phlebotomy. Cellular viability and counting, expression of immune-related genes, and functional evaluations were performed at each time point

Characterization of cell populations by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS)

One milliliter of blood from each time point (2 h, 7 h, 12 h and 24 h post phlebotomy) was used to quantify the relative frequencies of cell lineages (T and B lymphocytes, NK cells and monocytes) and the expression intensity of lineage markers (determined by the mean fluorescence intensity, MFI). This was achieved using the BD human Monocyte/NK cell (CD14/CD19/CD16/CD56) antibody cocktail (BD Biosciences, catalog #562,089) and PE-Cy™7 Mouse Anti-Human CD3-Clone SK7 (BD Biosciences, catalog # 557851), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Flow cytometry acquisition was performed on a BD Accuri C6 (BD Biosciences) cytometer; 50,000 events were collected for each processed sample. To ensure the quality of measurement, the performance of the cytometer was evaluated using validation beads to ensure coefficients of variation < 5% for the top peaks on each fluorescence detector and the forward scatter. Furthermore, fluorescence compensation was conducted before each sample acquisition. Data analysis was done using Flow-Jo (Treestar) version 10.0. The gating strategy included a selection of monocytes and B cells based on CD14+ and CD19+ expression and FSC/SSC (forward and side scatter features). NK cells and T cells were defined on total lymphocytes population by FSC/SSC and the expression of CD16 + CD56+ (NK) and CD3+ (T cells). The granulocyte population was defined based on FSC/SSC.

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells isolation

PBMCs were obtained by centrifugation of PBS-diluted (1:1) blood samples over a Ficoll-Hypaque gradient (Histopaque-1077, Sigma-Aldrich) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Cell viability was evaluated by exclusion of Trypan blue dye (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) at a 1:10 dilution and estimated as absolute numbers of viable and non-viable cells and as percent cell viability. Ten million PBMCs were collected, centrifuged at 450 x g and the pellet was resuspended in 1 mL TRIzol ® (Invitrogen, USA), stored at − 80 °C for 72 h and used for RNA extraction to evaluate gene expression. The remaining cells were stored at − 80 °C for one week in fetal bovine serum (FBS) complemented with 10% dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO). Subsequently, cells were gently thawed on a 37 °C water bath, washed twice with RPMI containing 10% FBS and immediately processed for evaluation of cell functions as described below.

Real-time PCR and RNA extraction

Total RNA was extracted from samples stored in TRIzol ®, as described by the manufacturer. The quantity and quality of the extracted RNA was evaluated in a Nanodrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer and the RNA integrity was evaluated by electrophoresis in 1.3% agarose gels. cDNA was synthesized using a high-capacity cDNA reverse transcription kit (Thermofisher Scientific). Gene expression of inflammatory mediators was evaluated using Taqman probes (Thermofisher Scientific) for CCL8 (Hs00271615_m1), CCL2 (Hs00234140_m1), CXCL3 (Hs00171061_m1), CXCL10 (Hs01124251_g1), CCR2 (Hs00704702_s1), CCR7 (Hs01013469_m1), TNFα (Hs00174128_m1), IL-1ß (Hs01555410_m1) and GAPDH (HS99999905_m1), in a BioRad® CFX-96 detection platform. Gene expression was quantified by the ΔΔCt method using GAPDH as the normalizing gene, and contrasting against control cells (2 h post-phlebotomy). Gene expression was expressed as fold change (2-ΔΔCt).

Secretion of TNF-α, IL-1β and CXCL10

PBMCs were seeded in 12 well plates at 5 × 106 cells/well in 1 mL of RPMI supplemented with 10% FBS. Cells were stimulated with 1 μg/mL ultrapure Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) (Sigma-Aldrich) for 12 h or left untreated. Culture supernatants were collected, and the secretion of TNFα, IL-1β and CXCL10 was assessed by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) using R&D system Human TNFα, IL-1β and CXCL10 DuoSet ELISA kits according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. Absorbance readings at 450 nm were performed on a Dinex microplate reader.

Statistical analysis

The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was used to determine the parametric or nonparametric distribution of the data. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) or Kruskal-Wallis test followed by multiple-comparison tests were employed for group comparisons. Statistical significance was defined at a p value < 0.05. All data were analyzed using Prism 6 software.

Results

The frequency of monocytes, NK cells, B cells and granulocytes, but not T cells, is maintained up to 24 h post-phlebotomy

Analysis of cell surface marker expression was conducted to evaluate the impact of time after phlebotomy on specific immune cell populations. The frequency of monocytes, NK cells, B cells (determined by expression and mean fluorescence intensity –MFI- of CD14, CD56 and CD19, respectively,) and granulocytes, was unaltered up to 24 h post phlebotomy (Fig. 2a-e). The frequency of CD3+ T cells significantly decreased from an average 65.06% at 2 h to 53.46% at 24 h (p < 0.05), despite no significant difference in the CD3 MFI (Fig. 2d). Decrease of the CD3+ cell population was accompanied by increase in CD3- lymphocytes (Additional file 1: Figure S1), suggesting time-dependent changes in expression of CD3, rather than an impact on cellular viability.

Phenotypic characterization of immune cell populations in peripheral blood. Frequencies (left column) and mean fluorescence intensity (right column) of CD3+, CD14+, CD56+ and CD19+ cells (a-d). Granulocytes were defined by forward and side scatter properties (e). Data are presented as mean or median depending on the distribution of the data. Statistical significance was estimated by one-way ANOVA or Kruskal-Wallis. *P < 0.05 compared to the control (2 h)

Viability of PBMCs and cell counts are maintained up to 24 h post-phlebotomy

PBMCs were isolated from peripheral blood and cell viability was measured. Absolute counts of viable cells were similar in all samples and across all time points (Fig. 3a). Likewise, the frequency of viable PBMCs was above 90% in samples processed at 2 h, 7 h and 12 h from all donors. A slight but non-significant reduction in the frequency of viable cells was observed at 24 h (Fig. 3b); however, cell viability was maintained above 85% for all except for one sample. Concordant with viability assays of isolated PBMCs, no significant difference in cell viability was observed for total leukocyte preparations (2 h: 97.06% ± 1.88 and 24 h: 94.9% ± 0.17).

Expression of immune related genes in PBMCs is altered by the time to sample processing

Gene expression of eight inflammatory mediators involved in the activation and recruitment of monocytes/macrophages (TNFα, CCL8, CCL2, CCR2, IL-1β), dendritic cells (CCR7), T cells (CXCL10) and neutrophils (CXCL3) was evaluated in isolated PBMCs in the absence of any ex-vivo stimulation. Expression of CXCL3, CCL2, CCR7 and IL-1β was unaltered at all time points when compared to the 2 h control (Fig. 4a-d). However, expression of TNFα, CCL8, CCR2 and CXCL10 was affected by the time-to-sample processing. While TNFα gene expression was strongly and significantly induced (> 3 fold), the levels of CCL8, CCR2 and CXCL10 were repressed as early as 7 h after sample procurement (Fig. 4e-h). Quality assessment of the extracted RNA by Nanodrop profiles and visual check on agarose gels showed that the RNA integrity of all samples was preserved; indicating that modulation of gene expression was not a result of RNA degradation (Additional file 1: Table S1 and Additional file 1: Figure 2). No differences in GAPDH expression (normalizer gene) were observed among patients and between samples obtained at different time points (Additional file 1: Figure S3).

Chemokine and cytokine gene expression in PBMCs. Gene expression of CXCL3, CCL2, CCR7, IL-1ß, TNFα, CCL8, CCR2 and CXCL10 (a-h), was measured by qRT-PCR. Data are presented as mean and statistical significance estimated by one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparison test. *: p < 0.05, **: p < 0.01, ***: p < 0.001

To assess whether the alterations in gene expression had a functional impact, secretion of TNFα, IL-1β and CXCL10 (each as a representative molecule of upregulated, unaltered and downregulated genes) was evaluated in LPS-stimulated PBMCs. Secretion of TNFα and IL-1β was homogeneous in all samples over the 24 h time frame (Fig. 5). CXCL10 secretion increased in a time-dependent manner up to 12 h and decreased at 24 h, however these changes were not statistically significant. These results suggest that despite a considerable effect elicited by the time-to-sample processing in the basal levels of gene expression, mitogen-induced protein secretion remains predominantly unaffected up to 24 h.

Discussion

Harmonized and controlled experimental methods are critical for all clinical and non-clinical human studies. Routinely, the checkpoints for quality control of blood samples and its derivatives rest on variables such as sample processing procedures, anticoagulants used, temperatures, incubation/exposure times, brand and lot of reagents, among others. However, sample pre-processing parameters that could influence the quality and stability of the biological material such as time-to-sample processing or time of day for sample procurement are not often considered. Results from this study revealed that a time delay between obtaining a peripheral blood sample and its processing, affects inflammatory gene expression and potentially cell functions, providing critical evidence of the importance of controlling blood sample handling variables prior to ex-vivo analyses.

Previous studies have evaluated the impact of time after phlebotomy and its relationship with the quality of data derived from immunological analyses [12, 17,18,19,20,21]. Despite their important contribution, these studies evaluated the effect of sample processing delay in a single immunologic parameter (cell function, cell count, activation markers or gene expression), and usually during just one time point (most of them after a 24 h time frame), limiting the accurate definition of sample processing times, especially when studies involve multiple clinical sites and multiple immunological parameters. To overcome this, our approach aimed to concomitantly analyze the dynamic effects of time to blood sample processing on multiple immune and cellular parameters.

Although not statistically significant, our results showed a reduction in the cellular viability at 24 h, which could have important biological implications. Similar findings were previously reported, where average viability within 8 h of processing was ∼92%, decreasing significantly to ∼84% when processing was delayed 24 h, concluding that for optimal cell viability and recovery, PBMCs must be processed and cryopreserved within 8 h after venipuncture [18]. Our data extend these observations and indicate that in terms of cell viability, blood samples could be processed up to 12 h after phlebotomy.

In the context of immunological assays and analyses of cell function, the time frame between phlebotomy and PBMCs isolation is critical [15, 18]. A delay in the processing of PBMCs over 8 h, has been shown to result in alterations of NK cells functions: decreased expression of chemokine receptors (CCR4 and CCR7), reduction of degranulation capacity and secretion of IFNγ and TNFα [22]. Similarly, a progressive impairment of antigen presenting cell function of plasmacytoid and myeloid dendritic cells and monocytes has been reported at 0, 6, 12 and 24 h between venipuncture and PBMC isolation [23]. Our data showed that the frequency of monocytes, NK cells, and B cells in whole blood was unaffected at early time points and up to 24 h after phlebotomy, concurring with prior studies and expanding towards earlier time-points of analysis [24]. However, our results revealed a significant decrease in the CD3+ T cell population at 24. Loss of CD3+ T cells occurred concomitantly with increase in the CD3 negative lymphocyte population, suggesting antigen loss rather than an impact on cell viability. Rapid internalization and recycling of the TCR:CD3 complex has been reported in resting T cells [25], potentially explaining the observed reduction in the CD3+ T cell population.

In the context of immune-related gene expression, we observed different patterns of expression among the analyzed genes. Whereas expression of TNFα was strongly upregulated in a time-dependent manner, and CCL8, CCR2 and CXCL10 were down-regulated at all time points after 2 h, and the expression of CXCL3, CCL2, IL-1β and CCR7 remained unchanged. Expression profiling in PBMCs using microarrays from human blood samples processed immediately or the next day after overnight incubation revealed that 31.7% of genes (2034 of the 6414 evaluated genes) were sensitive to ex-vivo incubation. A high proportion of these genes were involved in basic cellular processes such as transcriptional regulation, cell cycle progression, TNF-related functions, immune signaling, apoptosis and cytokines/chemokines signaling [12]. Interestingly, changes in gene expression have been reported to occur as early as 4 h post venipuncture [21]. These processes may reflect transcriptional events as an active response to cellular stress, and/or effects induced by alterations in cell-to-cell contact dynamics, which alert to an understanding of the basal gene expression patterns analyzed in blood samples prior to functional interpretation of gene expression profiles.

This study explored the effect of time to blood sample processing on a spectrum of immunological readouts. Overall, our findings indicated that blood samples processed after 12 h of phlebotomy should be carefully controlled and critically analyzed as alterations in cell viability and functionality are evidenced. This has important implications in multi-center/multi-site studies and field studies where time control can be challenging. Potential strategies to overcome this could include definition of a single time-point for sample processing within all clinical sites, inclusion of time-specific control samples to be collected simultaneously to the study samples (e.g. a blood sample from a study subject processed in parallel to one of a healthy volunteer as a normalizing control). Results presented herein provide an evidence base for the design of studies that involve human blood sampling and downstream analyses of immunological functions.

Abbreviations

- DMSO:

-

Dimethyl sulfoxide

- EDTA:

-

Ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid

- ELISA:

-

Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay

- FACS:

-

Fluorescence-activated cell sorting

- FBS:

-

Fetal bovine serum

- HIV:

-

Human immunodeficiency virus

- LPS:

-

Lipopolysaccharide

- MFI:

-

Mean fluorescence intensity

- PBMCs:

-

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells

- RT-PCR:

-

Real time polymerase chain reaction

References

Smith JG, et al. Establishing acceptance criteria for cell-mediated-immunity assays using frozen peripheral blood mononuclear cells stored under optimal and suboptimal conditions. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2007;14(5):527–37.

Aziz N, et al. Value of a quality assessment program in optimizing cryopreservation of peripheral blood mononuclear cells in a multicenter study. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2013;20(4):590–5.

Macchia I, Urbani F, Proietti E. Immune monitoring in cancer vaccine clinical trials: critical issues of functional flow cytometry-based assays. Biomed Res Int. 2013;2013:726239.

Caimari A, et al. Slc27a2 expression in peripheral blood mononuclear cells as a molecular marker for overweight development. Int J Obes. 2010;34(5):831–9.

Grunblatt E, et al. Gene expression as peripheral biomarkers for sporadic Alzheimer's disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2009;16(3):627–34.

Baechler EC, et al. Interferon-inducible gene expression signature in peripheral blood cells of patients with severe lupus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(5):2610–5.

Baine MJ, et al. Transcriptional profiling of peripheral blood mononuclear cells in pancreatic cancer patients identifies novel genes with potential diagnostic utility. PLoS One. 2011;6(2):e17014.

Kodama A, et al. A novel and simple method for generation of human dendritic cells from unfractionated peripheral blood mononuclear cells within 2 days: its application for induction of HIV-1-reactive CD4(+) T cells in the hu-PBL SCID mice. Front Microbiol. 2013;4:292.

Peng BG, et al. Expansion and activation of natural killer cells from PBMC for immunotherapy of hepatocellular carcinoma. World J Gastroenterol. 2004;10(14):2119–23.

Boyum A. Isolation of mononuclear cells and granulocytes from human blood. Isolation of monuclear cells by one centrifugation, and of granulocytes by combining centrifugation and sedimentation at 1 g. Scand J Clin Lab Invest Suppl. 1968;97:77–89.

Hartel C, et al. Ex vivo induction of cytokine mRNA expression in human blood samples. J Immunol Methods. 2001;249(1–2):63–71.

Baechler EC, et al. Expression levels for many genes in human peripheral blood cells are highly sensitive to ex vivo incubation. Genes Immun. 2004;5(5):347–53.

Liu H, et al. Comparative study of different procedures for the separation of peripheral blood mononuclear cells in cytokine-induced killer cell immunotherapy for hepatocarcinoma. Tumour Biol. 2015;36(4):2299–307.

Jackman RP, et al. Effects of blood sample age at time of separation on measured cytokine concentrations in human plasma. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2011;18(2):318–26.

Yang J, et al. The effects of storage temperature on PBMC gene expression. BMC Immunol. 2016;17:6.

Kaplan J, Nolan D, Reed A. Altered lymphocyte markers and blastogenic responses associated with 24 hour delay in processing of blood samples. J Immunol Methods. 1982;50(2):187–91.

McKenna KC, et al. Delayed processing of blood increases the frequency of activated CD11b+ CD15+ granulocytes which inhibit T cell function. J Immunol Methods. 2009;341(1–2):68–75.

Bull M, et al. Defining blood processing parameters for optimal detection of cryopreserved antigen-specific responses for HIV vaccine trials. J Immunol Methods. 2007;322(1–2):57–69.

dos Santos AP, et al. The sample processing time interval as an influential factor in flow cytometry analysis of lymphocyte subsets. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2007;102(1):117–20.

Nicholson JK, et al. Comparison of T and B cell analyses on fresh and aged blood. J Immunol Methods. 1984;73(1):29–40.

Barnes MG, et al. Gene expression profiles from peripheral blood mononuclear cells are sensitive to short processing delays. Biopreserv Biobank. 2010;8(3):153–62.

Naranbhai V, et al. Impact of blood processing variations on natural killer cell frequency, activation, chemokine receptor expression and function. J Immunol Methods. 2011;366(1–2):28–35.

Meier A, et al. Rapid loss of dendritic cell and monocyte responses to TLR ligands following venipuncture. J Immunol Methods. 2008;339(2):132–40.

Castro-Herrera V, et al. Influence of delayed sample processing on blood immune cell phenotypes, immune cell responses and serum anti-influenza vaccine antibody titres. J Immunol Methods. 2018;458:8–14.

Liu H, et al. On the dynamics of TCR:CD3 complex Cel surface expression and Down modulation. Immunity. 2000;13(5):665–75.l.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge the volunteers who participated in this study, members of the CIDEIM Clinical Unit, BD Biosciences for donation of the Accuri C6 platform and Dr. Varalasmy Elango for constructive discussions on blood sample processing in field study sites.

Funding

Research reported in this publication was supported by Wellcome Trust 107595/Z/15/Z the National Institute of Allergy And Infectious Diseases of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number U19AI129910 and US NIH International Fogarty Center Global Infectious Disease Research Training Program [Award Number D43 TW006589].. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and analyzed during current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conception and design of the study: AN, MP, MAG. Acquisition of data: AN, LG, JC. Analysis and interpretation of data: all authors. Manuscript writing: all authors. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved and monitored by the institutional review board for ethical conduct of research involving human subjects of the Centro Internacional de Entrenamiento e Investigaciones Médicas, CIDEIM (study code CIEIH-1258), in compliance with national (resolution 008430, República de Colombia, Ministry of Health, 1993) and international (Declaration of Helsinki and amendments, World Medical Association, Fortaleza, Brazil, October 2013) guidelines. All individuals voluntarily participated in the study and written informed consent was obtained from each participant.

Consent for publication

Not Applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional file

Additional file 1:

Figure S1. Representative dot plot showing the effect of sample processing time in CD3+ expression in lymphocyte populations from whole blood. Lymphocyte population was gated based on FSC/SSC and the frequencies of expression for NK cell marker CD16 + CD56+ PE (y axis) and CD3 (x axis) were determine for each time point. Table S1. Evaluation of RNA in PBMCs samples. The quantity and quality of the extracted RNA was evaluated in the Nanodrop ND-1000 spectrophotometer taking into account the ratio of absorbance 260/280 and 260/230. Figure S2. Evaluation of RNA integrity in PBMCs samples. Agarose gel electrophoresis of RNA samples for confirmation of RNA integrity by inspection of the 28S and 18S rRNA bands. Control samples: Lanes 1, 2, 3, 10, 14, 18, 22 and 26; 7 h samples: Lanes 4, 5, 6, 11, 15, 19, 23 and 27; 12 h samples: Lanes 12, 16, 20, 24, and 28; 24 h samples: Lanes 7, 8, 9, 13, 17, 21, 25 and 29. Figure S3. Evaluation of GAPDH gene expression in PBMCs. Gene expression was measured by qRT-PCR, each figure represents the CT value and its stability over time for samples from each volunteer. Individual and mean values are shown. No statistical differences were observed as estimated by one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparison test. (DOCX 446 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Navas, A., Giraldo-Parra, L., Prieto, M.D. et al. Phenotypic and functional stability of leukocytes from human peripheral blood samples: considerations for the design of immunological studies. BMC Immunol 20, 5 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12865-019-0286-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12865-019-0286-z