Abstract

Background

The polygenic risk score (PRS) is used to predict the risk of developing common complex diseases or cancers using genetic markers. Although PRS is used in clinical practice to predict breast cancer risk, it is more accurate for Europeans than for non-Europeans because of the sample size of training genome-wide association studies (GWAS). To address this disparity, we constructed a PRS model for predicting the risk of renal cell carcinoma (RCC) in the Korean population.

Results

Using GWAS analysis, we identified 43 Korean-specific variants and calculated the PRS. Subsequent to plotting receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves, we selected the 31 best-performing variants to construct an optimal PRS model. The resultant PRS model with 31 variants demonstrated a prediction rate of 77.4%. The pathway analysis indicated that the identified non-coding variants are involved in regulating the expression of genes related to cancer initiation and progression. Notably, favorable lifestyle habits, such as avoiding tobacco and alcohol, mitigated the risk of RCC across PRS strata expressing genetic risk.

Conclusion

A Korean-specific PRS model was established to predict the risk of RCC in the underrepresented Korean population. Our findings suggest that lifestyle-associated factors influencing RCC risk are associated with acquired risk factors indirectly through epigenetic modification, even among individuals in the higher PRS category.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Renal cell carcinoma (RCC) accounts for 90% of kidney cancers and ranks as the seventh most common cancer in the western world; it constitutes approximately 3% of all cancer diagnoses worldwide [1, 2]. In Asia, the incidence of RCC has increased due to the adoption of western lifestyles [3]. Well-known risk factors for RCC include smoking, excessive weight, and hypertension [4, 5]. Additionally, heritability plays a role in certain rare syndromes with predisposed germline mutations in genes such as VHL, FH, and MET [6, 7].

RCC is usually detected incidentally and asymptomatically when diagnosed at an early stage. Early detection through screening is crucial for reducing the morbidity and mortality associated with RCC [8, 9]. Several prediction models based on clinical, biochemical, historical, and lifestyle markers have been developed and validated to predict the diagnosis, grade, stage, and progression of several cancers, including RCC [10]. Similarly, polygenic risk score (PRS) models that use genetic markers to predict the risk of cancers have demonstrated sufficient predictive power, thereby enabling individualized risk management [11, 12].

Genomic architecture and predisposed allele frequencies vary among different ancestries [13]. PRS models utilizing genetic factors predict individual risk more accurately in Europeans compared to non-Europeans, primarily because the majority of genetic discoveries are made within European populations [14]. Europeans represent the largest ethnicity in training genome-wide association studies (GWAS) globally, accounting for 91% of the data, followed by East Asians at 4.9% [15]. Consequently, the accuracy of the Asian-specific PRS is affected by the relatively smaller sample size of genetic studies conducted in Asian populations, thereby lowering precision when estimating the relative risk for each individual [16]. To address this issue, we conducted a GWAS for RCC using genomic data from 992 cases and 3,431 controls in the Korean population.

Favorable lifestyle factors, such as avoiding tobacco and alcohol, following a healthy diet, and engaging in moderate physical activity, serve as an optimal approach to prevent and manage cancers or complex diseases [17]. Numerous studies have revealed that favorable lifestyle factors can mitigate the risk of cancer among individuals with high genetic risk [18,19,20]. The aim of this study is to identify RCC-susceptible germline variants specific to Koreans, construct a Korean PRS model to assess the risk of developing RCC based on these variants, and evaluate the performance of the PRS model. Furthermore, this study examined whether lifestyle-associated factors interact with the genetic risk expressed as PRS.

Methods

Study participants

This study involved 4,991 Korean individuals. We included the cases of 1,120 patients with RCC who were registered in the Seoul National University Prospectively Enrolled Registry for RCC-Nephrectomy (SUPER-RCC-Nx) and had their blood stored in the human biobank [21]. The control group consisted of 3,871 participants from the Ansan/Ansung study of the Korean Genome and Epidemiology Study (KoGES), a population-based prospective cohort study [22]. The baseline survey for the KoGES was conducted in 2001–2002, and a follow-up survey was carried out biennially for 14 years. The participants were selected based on specific criteria, excluding participants diagnosed with any cancer during the baseline survey and those diagnosed with kidney diseases during the follow-up survey. Genotyping was performed using the Korean Chip array, and the same array was used by the Korean National Institute of Health to genotype KoGES samples.

Korea biobank array (KoreanChip)

KoreanChip comprises more than 833,000 markers, among which 208,000 are functional markers that have been directly genotyped. These data were collected from an extensive dataset of 22 million variants identified in 2,576 sequenced Korean samples. The dataset encompasses 397 whole-genome sequences from the Korean Reference Genome, along with 2,179 whole-exome sequences sourced from various places, such as the T2D-GENES consortium, the Ansung and Ansan study, a cardiovascular disease sequencing study, and the Korean Children and Adolescents Obesity Cohort study [23].

Quality control (QC)

QC was performed to analyze the samples and variants. Individuals with sexual inconsistencies were excluded from the study based on the principle that the genotype data on the sex of an individual was inconclusive when the homozygosity rate is greater than 0.2 but less than 0.8. Samples with a call rate < 95%, excessive heterogeneity, and genetic relatedness were removed. Single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) with a call rate < 95%, minor allele frequency (MAF) < 5%, and Hardy–Weinberg Equilibrium (HWE) p-value < 1.0 × e− 6 were also excluded. Batch effect corrections were conducted for cases [24]. The subsequent step involved correcting the batch effects that arose between cases and controls. Importantly, regulations state that results obtained with KoreanChip must be normalized with 5,000 samples registered in the Korean consortium. Consequently, even though cases and controls underwent separate genotyping in different laboratories, they were effectively normalized to each other according to this regulation, which eliminated batch effects. To assess the effect of population substructure, principal component analysis (PCA) was performed before and after merging the datasets of the cases and controls. QC was completed using a combination of R v4.2, Plink v1.9, and bcftools git version 1.17-10 [25].

Imputation for missing values

Variants that were not directly genotyped or excluded during QC were imputed using Minimac4. Phasing was performed using Eagle v2.4. The ancestry was limited to East Asians with 1000 Genome project phase 3 for the reference genome panel. We filtered the imputed variants with a genotype quality R2 > 0.8 [26]. Post-imputation QC was conducted by applying the exclusion criteria of an MAF < 5% and an HWE p-value < 1.0 × e− 6. The percentage of imputed data after the post-QC step was 92.72%.

Statistical analysis for SNP selection

The samples were divided into two: discovery and validation datasets. The validation dataset, including 492 samples (approximately 10% of the total samples), was randomly extracted, whereas the remaining 4,915 samples were retained for the discovery set after undergoing QC. Association testing with RCC was conducted for the discovery dataset. Logistic regression was performed for the GWAS with covariates, including age, sex, body mass index (BMI), hypertension, and smoking. The associated SNPs were filtered using a threshold of 1.0 × e− 5 and a false discovery rate (FDR) of 0.05. LD pruning and fine mapping methods were used to identify causal SNPs for predicting RCC risk [27]. Hail 0.2 was used for statistical analysis.

PRS calculation and optimal performance

The PRS model was constructed using causal SNPs selected from the GWAS results with the validation dataset.

j:

individual

i:

variant of individual j

N:

number of SNPs in the score of individual j

where PRSj is the risk score for individual j, dosageij is the number of risk alleles for the i-th variant, \( \beta \)i is the natural logarithm of the odds ratio [ln(OR)] (or effect size, beta) of the i-th variant, and N is the number of SNPs in the score [28].

To compare the performance of the PRS models, systematically removing one SNP at a time and starting from the SNP with the highest p-value, a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was plotted, and the area under the curve (AUC) was calculated for different numbers of SNPs. The optimal PRS cut-off value was selected at the point of the maximal Youden’s index (sensitivity and specificity) performed using Plink v1.9 and the pROC package in R.

Association of PRS and lifestyle-associated factors with RCC risk

We selected BMI, smoking status, alcohol intake, and history of hypertension as lifestyle-associated factors related to RCC risk. Although a favorable lifestyle score is commonly calculated by considering obesity, tobacco use, alcohol intake, diet, and physical activity as lifestyle-associated factors, we replaced diet and physical activity with history of hypertension considering our present data and previous studies related to RCC risk [29, 30]. A favorable lifestyle was indicated by BMI < 30 kg/m2, no smoking, moderate alcohol intake, and no history of hypertension (see Additional File 1: Table S1). We assigned one point to each favorable lifestyle-associated factor. We categorized combined lifestyle scores into Ideal (favorable lifestyle score of 3 or 4), Intermediate (favorable lifestyle score of 2), and Poor (favorable lifestyle score of 0 or 1). PRS distributions were categorized into Low (0–40%), Intermediate (40–90%), and High (> 90%). We explored the association of favorable lifestyle-associated factors and PRS with RCC risk and further investigated the relationship between lifestyle-associated factors and RCC risk across the strata of PRS using a Cox proportional hazard model.

Results

Discovery phase findings

This study included 4,915 Koreans who were divided into two groups to identify risk variants and construct the PRS model. The discovery dataset comprised 992 cases and 3,431 controls, whereas the validation dataset comprised 112 cases and 380 controls. Although RCC can occur at any age, this study focused only on participants aged ≥ 40 years to examine the common effects of these factors on RCC risk (Table 1).

Batch effect correction was performed to address the technical variations or non-biological differences between measurements in different sample groups. Substantial correction of the case dataset was performed. Additionally, to assess the effect of the population substructure, PCAs were performed before and after merging the cases and controls. No specific population substructure was observed (see Additional File 1: Figure S1).

For the GWAS, logistic regression was used and 424 variants of 4,423 participants were selected [p < 1.0 × e− 5 and FDR 0.05] (Fig. 1). In the quantile–quantile plot (QQ-plot), the lambda value (λ) was 1.04, indicating no evidence of inflation or acceptable results for the GWAS (see Additional File 1: Figure S2). To identify highly associated causal variants, fine mapping was performed, and 43 out of 424 variants were selected as susceptible loci associated with RCC (see Additional File 1: Table S2).

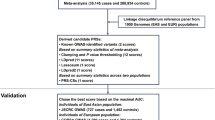

Workflow of the study. This study included patients with RCC from the SNUH and controls from the KoGES. RCC, renal cell carcinoma; SNUH, Seoul National University Hospital; KoGES, Korean Genome and Epidemiology Study; QC, quality control; GWAS, genome-wide association study; SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism; PRS, polygenic risk score; *, multiplication

Korean PRS construction for RCC risk and biological process of 31 variants

The Korean-specific PRS model was constructed using 43 SNPs on 492 Korean participants. The maximal AUC value for the PRS model was 77.4% when 31 variants out of 43 were selected (Fig. 2). Although the effect size was not significantly high, the aggregate of the weighted effect size of the 31 SNPs showed a high prediction rate. Of the 31 variants in the PRS model, 15 variants were in the intronic region, 15 in the intergenic region, and 1 downstream (Table 2; see Additional File 1: Figure S3). We annotated these variants with the genes they regulated to investigate whether they were associated with RCC risk. Functions and pathways of the genes regulated by the 15 variants in the intronic region are listed in Table 3.

PRS distribution of 31 Korean-specific SNPs and evaluation of PRS performance. The PRS was constructed based on 31 specific SNPs in the Korean population. (a) Density plot showing the different distribution of the PRS in cases and controls. (b) ROC curve for evaluating PRS performance. SNP, single nucleotide polymorphism; PRS, polygenic risk score; RCC, renal cell carcinoma; ROC, receiver operating characteristic

Relevance of lifestyle-associated factors to RCC risk across PRS strata

We categorized the combined lifestyle score as Ideal, Intermediate, and Poor and the PRS as Low, Intermediate, and High for 492 individuals. In the Cox proportional hazard model with combined lifestyle scores and RCC risk, the Poor lifestyle category (HR = 3.81, 95% CI: 2.33–6.22) involved a risk that was three times higher than that of the Ideal lifestyle category. A high genetic risk (PRS) was significantly associated with the RCC risk (HR = 10.22, 95% CI: 5.11–20.45). When lifestyle factors associated with the risk of RCC were stratified by PRS in the Cox proportional hazard model, the probability of RCC risk was higher in the poor lifestyle score category across PRS strata (Fig. 3).

Risk of RCC according to genetic and lifestyle-associated factors. The risk of RCC was affected by genetic and lifestyle-associated factors. (a) Association of genetic factor with RCC risk. (b) Association of lifestyle-associated factors with RCC risk. (c) Association of lifestyle-associated factors with the risk of RCC across strata of PRS. HR, hazard ratio; CI, confidence interval; N, number; RCC, renal cell carcinoma; PRS, polygenic risk score; p, p-value

Discussion

PRS model for predicting RCC risk in the Korean population

The recent advancements in sequencing techniques and development of novel data analysis methods have enabled the identification of disease-associated variants with increased accuracy and abundance, resulting in a more accurate PRS model. However, applying the same set of variants to the PRS model across different ethnic populations has resulted in several inaccuracies. In this prospective study, we identified 43 Korean-specific variants of RCC risk in a Korean population and constructed an optimal PRS model with 31 of the 43 variants, showing an AUC of 0.774. Although we used the Korean population dataset to avoid the inclusion of the different allele frequencies among various ancestries in our study, population substructure could affect the construction of a precise PRS model. Therefore, we performed PCA to explore whether population substructure affected the construction of our model; the results confirmed that our datasets were composed of the specific Korean population without any substructures.

Although RCC is a common tumor worldwide, only a few studies have been conducted on its prediction models. Scelo et al. identified seven new RCC risk loci and validated six known RCC risk loci by conducting a meta-analysis and performed PRS analysis on individuals of European ancestry. The authors focused on identifying rare variants for Europeans, which did not overlap with our Korean-specific variants [6]. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to construct a PRS model to predict the risk of RCC in the underrepresented Korean population.

Non-coding DNA variants and biological mechanisms

Fifteen of the 31 Korean-specific variants identified in this study indirectly contribute to cancer initiation and progression. These intronic variants regulate genes such as enhancers, repressors, or promoters, and are involved in biological functions and pathways associated with the development of cancers by exerting oncogenic or tumor-suppressive effects in multiple organs [31]. Well-annotated pathways were related to the genes affected by the variants implicated in RCC. For example, the RPTOR gene, located in the 17q25.3 region, codes for a subunit of the mTORC1 complex, which is crucial for regulating various cellular processes, such as assembly, localization, and substrate binding of mTORC1. The PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway is an intracellular pathway that plays a vital role in cell cycle regulation, including the G0 phase and cell proliferation. PI3K, a lipid kinase, produces phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-trisphosphate, a key second messenger that facilitates AKT translocation to the plasma membrane. AKT activation is central to fundamental cellular functions, such as cell proliferation and survival, as it phosphorylates various substrates. Dysregulation of this pathway is frequently observed in human cancers, particularly in RCC, and has been linked to aggressive tumor development and reduced survival rates [32,33,34]. The SUSD5 protein encoded by the SUSD5 gene in the 3p22.3 region is expected to have hyaluronic acid-binding activity and play a role in the Notch signaling pathway. Notch signaling is crucial in regulating cell fate, proliferation, and death during development. It operates mainly between adjacent cells as its ligands are transmembrane proteins. Despite its simplicity in intracellular signaling with no secondary messengers, the Notch pathway is part of various developmental processes, and its dysfunction is implicated in many cancers, including RCC [35, 36].

Relationship between lifestyle-associated factors and genetic risk expressed as PRS

Both lifestyle-associated factors and PRS were significantly associated with RCC risk, and lifestyle-associated factors affected RCC risk across PRS strata. However, Cox proportional hazard analysis showed no evidence that lifestyle-associated factors and PRS directly interacted with each other. Numerous studies have recently reported the relationship between epigenetic markers and lifestyle-associated factors, such as stress, smoking, alcohol use, and diet [37]. Various environmental factors epigenetically remodel the genome without altering its DNA sequence. Epigenetic markers influence the modulation of gene expression and thus play a critical role in health status and prevention of cancers and complex diseases [38].

The last 15 of the 31 Korean-specific variants identified in this study were intergenic variants. Many intergenic variants can affect gene regulation through epigenetic modifications, such as chromatin remodeling or histone modifications, including methylation or acetylation. Modulated expression of oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes affects cancer development [39]. In the present study, among the 15 intergenic variants, rs73149350 is situated in an open chromatin region of the genome. The open chromatin region is accessible and has a less condensed chromatin structure, facilitating the binding of transcription factors and other regulatory proteins to the DNA. The SEMA3C gene, in closest proximity to rs73149350, contributes to the promotion of cancer cell growth [40]. Therefore, rs73149350 may potentially regulate SEMA3C expression through processes such as chromatin remodeling or histone modification. This regulatory effect could have implications for the risk associated with RCC. However, it is important to note that further studies are needed to fully understand the biological mechanisms underlying the regulation of genes by these intergenic variants. The finding suggest that lifestyle-associated factors may indirectly affect acquired risk factors through epigenetic modulation [41].

Limitations and future directions

This study has certain limitations. First, we did not perform additional pathway or biological mechanism analysis of the intergenic variants. Without these analyses, the biological relevance of these variants in the context of RCC risk may remain unclear. Second, epigenetic association studies should be conducted to draw more accurate inferences. We must investigate the specific epigenetic mechanisms through which lifestyle-associated factors, such as stress, smoking, alcohol use, and diet, influence gene expression and how these modifications are related to RCC risk. This investigation could involve detailed epigenome-wide association studies to identify specific epigenetic changes associated with lifestyle factors. Further in-depth studies are required to explore the relationship between lifestyle-associated factors and genetic risk. These studies should consider incorporating such analyses to gain a deeper understanding of the underlying biology and potentially develop clinical applications.

Conclusion

The aim of the present study was to construct a Korean-specific PRS model that predicts the risk of RCC development and to explore the association of lifestyle-associated factors with the genetic factor influencing RCC risk. To mitigate the impact of ethnicity, GWAS analysis was exclusively performed on the underrepresented Korean population, leading to the identification of Korean-specific variants associated with RCC risk. The Korean-specific PRS model was constructed with 31 identified variants and demonstrated a robust prediction rate of 77.4%. Among the 31 variants, 15 intronic variants indirectly contributed to cancer initiation and progression through their involvement in key biological functions and pathways such as PI3K/AKT/mTOR or Notch signaling pathway. The remaining 15 intergenic variants potentially impact gene regulation through epigenetic modifications such as methylation or histone modification. Epigenetic modification is known to be influenced by environmental factors including lifestyle-associated factors. Furthermore, we investigated the association between lifestyle-associated factors, such as physical activity, alcohol use, smoking habit, and diet, and the risk of RCC development. Our results suggest that lifestyle-associated factors may indirectly influence acquired risk factors through epigenetic modification. However, further studies that delve deeper into these complex interactions and facilitate a comprehensive understanding of the interplay between genetic factors and lifestyle-associated factors in relation to RCC risk are warranted.

Data availability

All data used in this study are available at the National Biobank of Korea website (https://biobank.nih.go.kr/cmm/main/mainPage.do) and the Seoul National University Prospectively Enrolled Registry for Genitourinary Cancer (SUPER-GUC). The SUPER-GUC is available at https://doi.org/10.4111/icu.2019.60.4.235.

Abbreviations

- AUC:

-

Area under the curve

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- FDR:

-

False discovery rate

- GWAS:

-

Genome-wide association studies

- HWE:

-

Hardy–Weinberg Equilibrium

- KoGES:

-

Korean Genome and Epidemiology Study

- MAF:

-

Minor allele frequency

- PCA:

-

Principal component analysis

- PRS:

-

Polygenic risk score

- QC:

-

Quality control

- QQ-plot:

-

Quantile–quantile plot

- RCC:

-

Renal cell carcinoma

- ROC:

-

Receiver operating characteristic

- SNP:

-

Single nucleotide polymorphism

- SUPER-RCC-Nx:

-

Seoul National University Prospectively Enrolled Registry for RCC-Nephrectomy

References

Ueda K, Ogasawara N, Ito N, Ohnishi S, Suekane H, Kurose H, et al. Prognostic value of absolute lymphocyte count in patients with advanced renal cell carcinoma treated with nivolumab plus ipilimumab. J Clin Med. 2023;12:2417.

Zaccagnino A, Vynnytska-Myronovska B, Stöckle M, Junker K. An in vitro analysis of TKI-based sequence therapy in renal cell carcinoma cell lines. Int J Mol Sci. 2023;24:5648.

Padala SA, Barsouk A, Thandra KC, Saginala K, Mohammed A, Vakiti A, et al. Epidemiology of renal cell carcinoma. World J Oncol. 2020;11:79–87.

Ljungberg B, Campbell SC, Choi HY, Jacqmin D, Lee JE, Weikert S, et al. The epidemiology of renal cell carcinoma. Eur Urol. 2011;60:615–21.

Kabaria R, Klaassen Z, Terris MK. Renal cell carcinoma: links and risks. Int J Nephrol Renovasc Dis. 2016;9:45–52.

Scelo G, Purdue MP, Brown KM, Johansson M, Wang Z, Eckel-Passow JE, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies multiple risk loci for renal cell carcinoma. Nat Commun. 2017;8:15724.

Dizman N, Philip EJ, Pal SK. Genomic profiling in renal cell carcinoma. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2020;16:435–51.

Singleton RK, Heath AK, Clasen JL, Scelo G, Johansson M, Calvez-Kelm FL, et al. Risk prediction for renal cell carcinoma: results from the European prospective investigation into cancer and nutrition (EPIC) prospective cohort study. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2021;30:507–12.

Shuch B, Zhang J. Genetic predisposition to renal cell carcinoma: implications for counseling, testing, screening, and management. J Clin Oncol. 2018;36:JCO2018792523.

Lewis CM, Vassos E. Polygenic risk scores: from research tools to clinical instruments. Genome Med. 2020;12:44.

Sud A, Turnbull C, Houlston R. Will polygenic risk scores for cancer ever be clinically useful? NPJ Precis Oncol. 2021;5:40.

Collister JA, Liu X, Clifton L. Calculating polygenic risk scores (PRS) in UK Biobank: a practical guide for epidemiologists. Front Genet. 2022;13:818574.

Oak N, Cherniack AD, Mashl RJ, Analysis Network TCGA, Hirsch FR, Ding L et al. (2020). Ancestry-specific predisposing germline variants in cancer. Genome Med. 2020;12:51.

Martin AR, Kanai M, Kamatani Y, Okada Y, Neale BM, Daly MJ. Clinical use of current polygenic risk scores may exacerbate health disparities. Nat Genet. 2019;51:584–91.

Fitipaldi H, Franks PW. Ethnic, gender and other sociodemographic biases in genome-wide association studies for the most burdensome non-communicable diseases: 2005–2022. Hum Mol Genet. 2023;32:520–32.

Ho WK, Tan MM, Mavaddat N, Tai MC, Mariapun S, Li J, et al. European polygenic risk score for prediction of breast cancer shows similar performance in Asian women. Nat Commun. 2020;11:3833.

Zhang YB, Pan XF, Chen J, Cao A, Zhang YG, Xia L, et al. Combined lifestyle factors, incident cancer, and cancer mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Br J Cancer. 2020;122:1085–93.

Carr PR, Weigl K, Jansen L, Walter V, Erben V, Chang-Claude J, et al. Healthy lifestyle factors associated with lower risk of colorectal cancer irrespective of genetic risk. Gastroenterology. 2018;155:1805–1815e5.

Arthur RS, Wang T, Xue X, Kamensky V, Rohan TE. Genetic factors, adherence to healthy lifestyle behavior, and risk of invasive breast cancer among women in the UK Biobank. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2020;112:893–901.

Jin G, Lv J, Yang M, Wang M, Zhu M, Wang T, et al. Genetic risk, incident gastric cancer, and healthy lifestyle: a meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies and prospective cohort study. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:1378–86.

Jeong CW, Suh J, Yuk HD, Tae BS, Kim M, Keam B, et al. Establishment of the Seoul National University prospectively enrolled Registry for Genitourinary Cancer (SUPER-GUC): a prospective, multidisciplinary, bio-bank linked cohort and research platform. Investig Clin Urol. 2019;60:235–43.

Kim Y, Han BG, KoGES group. Cohort Profile: the Korean Genome and Epidemiology Study (KoGES) Consortium. Int J Epidemiol. 2017;46:e20.

Moon S, Kim YJ, Han S, Hwang MY, Shin DM, Park MY, et al. The Korea Biobank array: design and identification of coding variants associated with blood biochemical traits. Sci Rep. 2019;9:1382.

Wickland DP, Ren Y, Sinnwell JP, Reddy JS, Pottier C, Sarangi V, et al. Impact of variant-level batch effects on identification of genetic risk factors in large sequencing studies. PLoS ONE. 2021;16:e0249305.

Turner S, Armstrong LL, Bradford Y, Carlson CS, Crawford DC, Crenshaw AT et al. Quality control procedures for genome-wide association studies. Curr Protoc Hum Genet. 2011;Chap. 1:Unit1.19.

Das S, Forer L, Schönherr S, Sidore C, Locke AE, Kwong A, et al. Next-generation genotype imputation service and methods. Nat Genet. 2016;48:1284–7.

Uffelmann E, Huang QQ, Munung NS, De Vries J, Okada Y, Martin AR, et al. Genome-wide association studies. Nat Rev Methods Primers. 2021;1:59.

Choi SW, Mak TS, O’Reilly PF. Tutorial: a guide to performing polygenic risk score analyses. Nat Protoc. 2020;15:2759–72.

Azawi N, Ebbestad FE, Nadler N, Mosholt KSS, Axelsen SS, Geertsen L, et al. Lifestyle and clinical factors in a nationwide stage III and IV renal cell carcinoma study. Cancers (Basel). 2023;15:4488.

Meer R, van de Pol J, van den Brandt PA, Schouten LJ. The association of healthy lifestyle index score and the risk of renal cell cancer in the Netherlands cohort study. BMC Cancer. 2023;23:156.

Lange M, Begolli R, Giakountis A. Non-coding variants in cancer: mechanistic insights and clinical potential for personalized medicine. Noncoding RNA. 2021;7:47.

Osaki M, Oshimura M, Ito H. PI3K-Akt pathway: its functions and alterations in human cancer. Apoptosis. 2004;9:667–76.

Guo H, German P, Bai S, Barnes S, Guo W, Qi X, et al. The PI3K/AKT pathway and renal cell carcinoma. J Genet Genomics. 2015;42:343–53.

Miricescu D, Balan DG, Tulin A, Stiru O, Vacaroiu IA, Mihai DA, et al. PI3K/AKT/mTOR signalling pathway involvement in renal cell carcinoma pathogenesis (review). Exp Ther Med. 2021;21:540.

Bray SJ. Notch signalling: a simple pathway becomes complex. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2006;7:678–89.

Xiao W, Gao Z, Duan Y, Yuan W, Ke Y. Notch signaling plays a crucial role in cancer stem-like cells maintaining stemness and mediating chemotaxis in renal cell carcinoma. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2017;36:41.

Maleknia M, Ahmadirad N, Golab F, Katebi Y. Haj Mohamad Ebrahim Ketabforoush A. DNA methylation in cancer: epigenetic view of dietary and lifestyle factors. Epigenet Insights. 2023;16:25168657231199893.

Lorenzo PM, Izquierdo AG, Rodriguez-Carnero G, Fernández-Pombo A, Iglesias A, Carreira MC, et al. Epigenetic effects of healthy foods and lifestyle habits from the southern European Atlantic diet pattern: a narrative review. Adv Nutr. 2022;13:1725–47.

Weinberg DN, Papillon-Cavanagh S, Chen H, Yue Y, Chen X, Rajagopalan KN, et al. The histone mark H3K36me2 recruits DNMT3A and shapes the intergenic DNA methylation landscape. Nature. 2019;573:281–6.

Peacock JW, Takeuchi A, Hayashi N, Liu L, Tam KJ, Nakouzi NA, et al. SEMA3C drives cancer growth by transactivating multiple receptor tyrosine kinases via plexin B1. EMBO Mol Med. 2018;10:219–38.

Tsalenchuk M, Gentleman SM, Marzi SJ. Linking environmental risk factors with epigenetic mechanisms in Parkinson’s disease. npj Parkinsons Dis. 2023;9:123.

Guo H, Lu Y, Wang J, Liu X, Keller ET, Liu Q, et al. Targeting the notch signaling pathway in cancer therapeutics. Thorac Cancer. 2014;5:473–86.

Sakthianandeswaren A, Parsons MJ, Mouradov D, MacKinnon RN, Catimel B, Liu S, et al. MACROD2 haploinsufficiency impairs catalytic activity of PARP1 and promotes chromosome instability and growth of intestinal tumors. Cancer Discov. 2018;8:988–1005.

Dibble CC, Cantley LC. Regulation of mTORC1 by PI3K signaling. Trends Cell Biol. 2015;25:545–55.

Zhang S, Sui L, Zhuang J, He S, Song Y, Ye Y, et al. ARHGAP24 regulates cell ability and apoptosis of colorectal cancer cells via the regulation of P53. Oncol Lett. 2018;16:3517–24.

Pehkonen H, de Curtis I, Monni O. Liprins in oncogenic signaling and cancer cell adhesion. Oncogene. 2021;40:6406–16.

Roy F, Laberge G, Douziech M, Ferland-McCollough D, Therrien M. KSR is a scaffold required for activation of the ERK/MAPK module. Genes Dev. 2002;16:427–38.

Li YX, Yu ZW, Jiang T, Shao LW, Liu Y, Li N, et al. SNCA, a novel biomarker for Group 4 medulloblastomas, can inhibit tumor invasion and induce apoptosis. Cancer Sci. 2018;109:1263–75.

Jeon YJ, Lee KY, Cho YY, Pugliese A, Kim HG, Jeong CH, et al. Role of NEK6 in tumor promoter-induced transformation in JB6 C141 mouse skin epidermal cells. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:28126–33.

Alfert A, Moreno N, Kerl K. The BAF complex in development and disease. Epigenetics Chromatin. 2019;12:19.

Chapman RM, Tinsley CL, Hill MJ, Forrest MP, Tansey KE, Pardiñas AF, et al. Convergent evidence that ZNF804A is a regulator of pre-messenger RNA processing and gene expression. Schizophr Bull. 2019;45:1267–78.

Yi Y, Qiu Z, Yao Z, Lin A, Qin Y, Sha R, et al. CAMSAP1 mutation correlates with improved prognosis in small cell lung cancer patients treated with platinum-based chemotherapy. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021;9:770811.

Khalyfa AA, Punatar S, Aslam R, Yarbrough A. Exploring the inflammatory pathogenesis of colorectal cancer. Diseases. 2021;9:74.

Hoang T, Fenne IS, Madsen A, Bozickovic O, Johannessen M, Bergsvåg M, et al. cAMP response element-binding protein interacts with and stimulates the proteasomal degradation of the nuclear receptor coactivator GRIP1. Endocrinology. 2013;154:1513–27.

Rodger EJ, Chatterjee A, Stockwell PA, Eccles MR. Characterisation of DNA methylation changes in EBF3 and TBC1D16 associated with tumour progression and metastasis in multiple cancer types. Clin Epigenetics. 2019;11:114.

Acknowledgements

We thank the National Biobank of Korea and the Center for Disease Control and Prevention for the permission to use bioresources (NBK-2022-037). Additionally, we thank Seoul National University Hospital Human Biobank, a member of the National Biobank of Korea for approving the use of bioresources which were obtained with informed consent under Institutional Review Board-approved protocols (H-2103-196-1208).

Funding

This study was supported by a grant from the National R&D Program for Cancer Control, Ministry of Health and Welfare, Republic of Korea (HA17C0039) and the Cooperative Research Program of Basic Medical Science and Clinical Science from Seoul National University College of Medicine (800-20220315).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

CWJ and JYH designed the study. JHH and SHJ performed genotyping. CK, HHK, and CWJ collected clinical data. JYH analyzed and interpreted the data. JYH and CWJ prepared the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Seoul National University Hospital (H-2103-196-1208), and all study participants provided written informed consent.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Hong, J.Y., Han, J.H., Jeong, S.H. et al. Polygenic risk score model for renal cell carcinoma in the Korean population and relationship with lifestyle-associated factors. BMC Genomics 25, 46 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-024-09974-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-024-09974-w