Abstract

Background

With a growing number of loci associated with late-onset (sporadic) Alzheimer’s disease (AD), the polygenic contribution to AD is now well established. The development of polygenic risk score approaches have shown promising results for identifying individuals at higher risk of developing AD, thereby facilitating the development of preventative and therapeutic strategies. A polygenic hazard score (PHS) has been proposed to quantify age-specific genetic risk for AD. In this study, we assessed the predictive power and transferability of this PHS in an independent cohort, to support its clinical utility.

Results

Using genotype and imaging data from 780 individuals enrolled in the Australian Imaging, Biomarkers and Lifestyle (AIBL) study, we investigated associations between the PHS and several AD-related traits, including 1) cross-sectional Aβ-amyloid (Aβ) deposition, 2) longitudinal brain atrophy, 3) longitudinal cognitive decline, 4) age of onset. Except in the cognitive domain, we obtained results that were consistent with previously published findings. The PHS was associated with increased Aβ burden, faster regional brain atrophy and an earlier age of onset.

Conclusion

Overall, the results support the predictive power of a PHS, however, with only marginal improvement compared to apolipoprotein E alone.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The ε4 allele of the apolipoprotein E (APOE) gene is the strongest genetic risk factor for late onset AD [1]. However, polygenic or oligogenic [2] contributions to AD are now widely acknowledged. In recent years, genome wide association studies (GWAS) and next-generation sequencing efforts have facilitated the identification of a number of disease-onset-associated single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) with much smaller effect size [3, 4]. Collectively, these genetic variations could make a significant contribution to age-at-onset AD risk. The combined effect of these inherited genetic variations can be quantified and expressed as a polygenic risk score (PRS). The development and validation of a reliable PRS for AD could contribute to solving a major public health challenge by identifying the age-at-onset of individuals at high risk of developing the disease and therefore enable early screening and preventive therapies [5]. Typically, PRSs are constructed as the weighted sum of allele counts, where the weights correspond to the effects (β coefficients) of each SNP, extracted from a SNPs-disease association analysis (e.g. logistic regression for case-control studies) [6]. The development of PRSs for age-at-onset of AD have demonstrated promising results with prediction capabilities showing over 80% accuracy in some cases [7, 8].

A polygenic hazard score (PHS) approach has also been developed for AD [9]. This PHS goes beyond AD risk prediction by providing estimates of individual age-specific risk for developing AD. Moreover, the PHS has been shown to be associated with Aβ-amyloid (Aβ) accumulation, accelerated cognitive decline and neurodegeneration in susceptible brain regions. In this study we aim to assess the useability and replicability of PHS in an independent cohort.

Materials and methods

Sample population

The study used data from the Australian Imaging, Biomarkers and Lifestyle (AIBL) cohort, of which the design, enrolment process, neuropsychological assessments and diagnostic criteria have been previously described [10]. Of the 1572 participants enrolled in the AIBL study, we restricted the analysis to individuals having both genotype and imaging data available (N = 780). Longitudinal data was collected every 18 months over multiple years (mean = 4.8 years, SD = 2.1). Participants were classified as those with Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI) [11] or AD [12] when the clinical criteria for diagnosis were met. In the absence of these features a classification of Cognitively Normal (CN) was given by a clinical review panel, blinded to Aβ-PET status (see below). Ethics approval for the AIBL study and all experimental protocols was provided by Austin Health, St Vincent’s Health, Hollywood Private Hospital and Edith Cowan University. All experiments and methods were carried out in accordance with approved guidelines and regulations and all volunteers gave written informed consent before participating in the study.

MRI and PET imaging

All subjects underwent a 3 T MRI and Aβ-PET imaging. T1 MPRAGE MRI was obtained at 3 T using the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI) magnetization-prepared rapid gradient echo (MPRAGE) protocol, with in-plan resolution of 1 × 1 mm and 1.2 mm slice thickness. Freesurfer was used to estimate all cortical volumes from the T1 [13]. All volumes were corrected for age and ICV using a regression approach and reference population composed of healthy subjects (CN, Aβ negative, MMSE> 28, CDR = 0, APOE non-ε4). Left and right volumes were averaged.

Aβ-PET imaging was performed with one of five radiotracers: [11C]-PiB, [18F]-flutemetamol (FLUTE), [18F]-florbetapir (FBP), [18F]-florbetaben (FBB), and [18F]-NAV4694 (NAV). A 20- minute acquisition was performed 50 minutes post-injection of PiB, NAV and FBP, and 90 minutes post-injection of FLUTE and FBB. Due to the difference in SUVR dynamic ranges of each Aβ tracer, the Centiloid (CL) scale was used to provide a standard scale for Aβ-PΕΤ quantification [14], with 0 representing the typical Aβ-PΕΤ in young controls, and 100 the typical Aβ-PET in mild AD patients. Values equal to or above 20 CL were considered representative of abnormal levels of Aβ deposition [15]. CL were generated using CapAIBL software [14] and estimated in three regions of interest (whole neocortex, frontal and posterior cingulate). CL values were also projected onto the individual cortical surface and then transferred to a cortical atlas where statistical analyses were performed [16].

Cognitive scores

All AIBL participants complete a battery of neuropsychological tests as previously described [10]. The resulting data were used to calculate cognitive composite scores to assess recognition memory, executive function and episodic recall memory. Briefly, the composites were computed by standardising the outcome measure for each neuropsychological test to be included, using the baseline mean and standard deviation for the cognitively normal sample, then averaging those standardised scores. Each composite consists of the following tests; recognition memory (California Verbal Learning Test Second Edition and Rey Complex Figure Test), executive function (Controlled Oral Word Association Test and Category Switching), and episodic recall memory (California Verbal Learning Test Second Edition, Logical Memory II, and Rey Complex Figure Test) (Harrington reference). Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) sum of boxes (CDRSB) score was also used to assess clinical progression.

Age of onset definition

The age of onset of abnormal levels of amyloid deposition was determined as follows: First a progression curve giving for Aβ-amyloid deposition as a function of disease progression time was constructed as described in [17, 18]. Then, the participants’ age of onset was estimated by using the progression curve to calculate the elapsed time between a participant passing the CL threshold and reaching their mean longitudinal Aβ-amyloid levels. Finally, this value was subtracted from their mean longitudinal age to get the age at onset.

Genetic data and Polygenic hazard score

Genome wide genetic data was ascertained from the OmniExpressHumanExome+ BeadChip (Illumina, USA) as previously described [10]. A polygenic hazard score was then derived from this genetic data for each individual following the methodology described previously [9]. Briefly, the approach consists in three steps. First, a list of 1854 SNPs implicated with AD (p-values < 10− 5) was extracted from the published summary statistics (p-values and odds ratios) generated by the IGAP consortium [4]. Second, a forward stepwise regression to identify a subset of 31 SNPs, in addition to the two APOE variants, that were associated with AD age of onset. Finally, for each patient, a polygenic hazard score predicting the individual’s risk of developing AD, given their polygenic profile and age was derived. In the analyses we assessed the PHS as a continuous measure, quantifying individual risk for AD, and as a dichotomous variable (high and low). To directly replicate the findings from Tan et al. [19], we used the same grouping method, defining high PHS by 1 standard deviation (SD) above the mean and low PHS by 1 SD below the mean (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Statistical analyses

Association with cross-sectional Aβ deposition

We used linear regression to investigate the relationship between PHS and regional brain Aβ deposition at baseline. Three main areas were investigated: neocortical, frontal cortex and posterior cingulate. In this cross-sectional analysis, we controlled for age, gender, level of education in years and APOE ε4 status (0 = no ε4 allele, 1 = 1 or 2 ε4 alleles). To evaluate the contribution of PHS and APOE ε4 status in the linear regression, we used likelihood ratio tests to compare models with and without these terms.

To further assess the association between PHS and Aβ deposition, beyond the role APOE, we performed the same analysis in two sub-cohorts containing exclusively APOE ε4 carriers (N = 278; CN = 161, MCI = 58, AD = 59) and non-carriers (N = 502; HC = 412, MCI = 66, AD = 24). In these subsequent analyses, we used the same linear regression, however, we did not control for APOE ε4 status due to the lack of variation in these sub-populations. All the results were adjusted for multiple comparisons using false discovery rate (FDR). The same analysis was performed at a vertex level on a template cortical surface.

Association with regional brain atrophy

We used linear mixed-effects models to evaluate the relationship of PHS with longitudinal volume change in 33 regions of interest from the Desikan-Killiany atlas in Freesurfer [20]. As volumes were previously controlled for intra-cranial volume (ICV) and age using a healthy sub-population we only controlled for gender, level of education in years and APOE ε4 status (0 = no ε4 allele, 1 = 1 or 2 ε4 alleles). In these analyses, we also controlled for sex, education, and APOE status. We then examined the simple effects by comparing slopes of volume loss over time for individuals at high (+ 1 SD) and low (− 1 SD) levels of PHS [19, 21].

Association with longitudinal cognitive decline

For comparative purposes, we used the same linear mixed effects models as described in the original Desikan paper [19]. The only deviation made from this model was the use of the CL value from the frontal cortex instead of the standard uptake volume ratio (SUVR). Therefore, the final linear mixed effect model was defined as follows:

This model was used to investigate the association between PHS and cognitive decline and clinical progression rate (represented as Δc) across four measures: recognition, executive function, episodic recall and CDR-SB. In this model, Time represented the number of years since the baseline visit. The APOE term indicated the presence/absence of APOE ε4 allele, encoded as a binary variable (0 = no ε4 allele, 1 = 1 or 2 ε4 alleles) and the term (1| Patient) corresponded to the random intercept. Continuous variables were centred and scaled in all the analyses. Further, to assess the original model and limit potential over-specification, we used a stepwise variable selection approach (backward selection) and identified a reduced model based on superior model fit (Akaike information criterion).

Association with age of onset of abnormal levels of Aβ deposition

Cox proportional hazards models of survival were performed to compare the time taken to reach abnormal levels of neocortical Aβ between participants with low versus high PHS scores (threshold at 1.04), adjusted baseline age, gender and years of education. The definition for survival time was the number of years between birth and a) having a PET scan indicating abnormal levels of Aβ (classed here an event, age of onset), b) withdrawing from the study (censored), or c) the last completed follow-up examination without an event (censored). For some individuals it was necessary to impute the date at which their Aβ levels became abnormal as previously published [22]. The age at which 50% of the cohort (median age) reached abnormal levels of Aβ, was reported.

Results

Demographics

The study was conducted on a cohort of 780 participants enrolled in the AIBL study [23] (422 females, 358 males). Population demographic information is displayed in Table 1. Comparing demographic and clinical characteristics between diagnoses, AD participants were older than CN and MCI participants (AD: 75.0 [SD: 7.85], MCI: 75.6 [SD: 7.13], CN: 72.9 [SD: 6.12], p < 0.001) and were more likely to carry at least one copy of APOE ε4 allele (AD: 71.1%, MCI: 46.8%, HC: 28.1%, p < 0.001). As expected, the PHS were significantly higher in AD participants (AD: 0.847 [SD: 0.941], MCI: 0.415 [SD: 0.967], CN: 0.0271 [SD: 0.763], p = 8.25e− 08). This result was consistent in the sub-population consisting of APOE ε4 carriers only (AD: 1.33 [SD: 0.62], MCI: 1.29 [SD: 0.66], CN: 1.04 [SD: 0.55], p = 9.55e− 4). However, in the APOE ε4 non-carrier subgroup, the difference of PHS across clinical classification was not seen (AD: -0.35 [SD: 0.31], MCI: -0.35 [SD: 0.34], CN: -0.37 [SD: 0.36], p = 0.895).

Association with cross-sectional Aβ deposition

Using linear regression to evaluate the relationship between PHS and Aβ burden at baseline, we found that increased PHS values were associated with higher Aβ deposition. Similar results were obtained when looking at CL values specifically in the three areas investigated, neocortical, frontal cortex and posterior cingulate, with stronger effects systematically obtained in the posterior cingulate region, followed by the frontal cortex and then the neocortical region (Table 2). These results were consistent in the sub-populations composed exclusively of APOE ε4 carriers and non-carriers, although with less significant effects. We then used likelihood ratio tests to determine if the addition of PHS and APOE ε4 status in a model resulted in improvements in the fit. The addition of APOE ε4 status (β = 39.5, SE = 2.8, p = 8.05e− 39) and PHS (β = 24.2, SE = 1.55, p = 3.74e− 48), individually, both resulted in statistically significant improvements from a base model controlling for age, gender and education only. However, the addition of PHS in a model already controlling for APOE ε4 status was not significant in any of the three areas investigated (frontal cortex, p = 0.066; posterior cingulate, p = 0.1306; neocortical, p = 0.08).

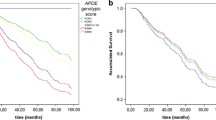

Association with regional brain atrophy

In the linear-mixed effect analysis, PHS was significantly associated with cortical volume changes in most regions of interest. The effects were strongest in regions from the AD cortical signature, including temporal lobe, entorhinal cortex, posterior cingulate and precuneus. The cortical atrophy was fastest in individuals with high PHS (Fig. 1). However, when looking at non-ε4 carriers only, none of the associations between PHS and cortical atrophy remained significant after controlling for multiple comparisons. In addition, the effect sizes were considerably reduced (Supplementary Fig. 2).

Association with cognitive decline

In the linear mixed model analyses, we did not find any significant association between PHS and cognitive decline. The analyses were restricted to non-AD individuals (CN + MCI and CN only) and the results were consistent across the three cognitive domains investigated (Table 3). Further, comparing individuals with high PHS against low PHS, there was no significant difference in rate of cognitive decline between the two groups. Likelihood ratio tests comparing linear-mixed effects models with and without the PHS term, showed that the presence of PHS in the model resulted in minor improvement in CDR-SB (X2 = 6.29, p = 0.043) and Episodic recall (X2 = 6.58, p = 0.037). However, the addition of PHS did not result in a better fit in the model predicting Executive function (X2 = 2.83, p = 0.24).

Association with age of onset of abnormal levels of Aβ deposition

The age of onset of individuals with a high PHS (> 1.04) was significantly lower than individuals with a low PHS (<− 0.67). The median age at which AIBL participants with a high PHS reached abnormal levels of Aβ (Fig. 2) was 67.6 years (CI 95% [65.6, 68.6]), 12.4 years earlier than those with a low PHS (80 years, CI 95% [78.3, 82.4]). The hazard ratio comparing the high PHS versus the low PHS group was 3.9 (CI 95% [3.1, 4.9], log rank test p = 3.72e− 17). Restricting this analysis to ε3/ε3 individuals only, the high PHS group still had an earlier age of onset (73.9 years, CI 95% [72.4, 78.2]) compared to the low PHS population (82.4 years, CI 95% [76.8.4, 84.2]), with a hazard ratio of 1.8 (CI 95% [0.9, 3.2], log rank test p = 0.072).

Discussion

Over the last decade, GWAS have clearly demonstrated that common complex diseases are typically associated with hundreds or thousands of genetic markers, collectively contributing to disease risk. This highly polygenic underpinning has been utilised in PRS by aggregating the effect of multiple genetic variants into a single score to predict disease risk. PRS have shown predictive values in several complex disorders, however, the approach does not account for age of onset, which is critical for neurodegenerative disease such as AD. The recent development of polygenic hazard score overcomes this limitation by predicting individuals’ age-specific risk of AD development [9]. In this study, we attempted to replicate the findings from Tan et al. [19] and assess the utility of a PHS in an independent cohort. While investigating the relationship between PHS and cross-sectional Aβ deposition, we found that the PHS had slightly better predicting capabilities than using APOE ε4 status alone. This result was expected considering the effects of the APOE ε2 and ε4 alleles were already accounted for in the calculation of the PHS. However, the marginal improvement in models to predict Aβ deposition observed when using PHS, suggests that the number of APOE ε4 alone can provide comparable predictive information. The major contribution of APOE in the PHS definition is evident when looking at the stratified score distribution (Supplementary Fig. 1). Individuals falling in the low PHS bracket (1 SD below the mean) are all ε4 non-carriers, while all ε4/ε4 individuals, conversely, are found in the high PHS group (1 SD above the mean). Nonetheless, we were able to find associations between PHS and regional Aβ deposition and brain atrophy in non-ε4 individuals. Although with relatively small effect sizes, these associations are consistent with the findings reported by Tan et al. [19] and support the claim that the PHS can provide predicting capabilities beyond APOE status.

Investigating cognitive domains, we did not find any evidence of association between PHS and longitudinal cognitive decline. These analyses were performed on non-demented individuals (N = 697) with a proportion of 82% CN and 18% MCI. This ratio was very different from the study cohort utilised in Tan et al., which consisted of about 36% CN and 64% MCI. Considering that healthy individuals have a much less pronounced cognitive decline trajectory, the over-representation of CN in our dataset could have impacted the results. Further, the linear mixed model used in this study was slightly different than the one presented in the original paper. Specifically, we used the CL values instead of the frontal florbetapir SUVR. Although, it is not expected that this deviation would generate differing results, they could have impacted and decreased the strength of the associations between PHS and cognitive decline.

Investigating the associations between PHS and age of onset, we found that individuals with a high PHS had a significantly younger age of onset (67.6 years) than low PHS individuals (80 years). Among the APOE ε3/ε3 population, high PHS individuals had an expected age of onset approximatively 8 years younger than low PHS individuals. Although the difference was less noticeable in the ε3/ε3 population, this result showed that the polygenic information, beyond the APOE ε4 allele, was useful for predicting the age of disease onset.

Compared to traditional polygenic risk scores, which provide a lifetime risk of developing a disease, the polygenic hazard scores provide prediction on age-specific risk of disease development. This estimation of instantaneous risk for developing AD is valuable additional information, as it could improve monitoring disease progression and facilitate timely intervention. In this study, we showed that the PHS had utility in predicting abnormal Aβ deposition, brain atrophy and age of disease onset. However, the results suggested that APOE genotype alone could provide comparable predictive capabilities, suggesting that APOE remains the main component of the PHS. This disproportionate contribution is mainly due to the large weight attributed to APOE alleles, which shadows the less extensive effects of the other disease-associated variants utilised in the score calculation. This is the case in both PRS and PHS approaches and reflect the difficulty in classifying AD genetic risk above and beyond APOE ε4. Recent studies have suggested that the use of less stringent significance threshold for SNPs selection could results in better performing scores [7, 8, 24]. This strategy could potentially further improve the prediction accuracy of the PHS. However, caution must be taken as the inclusion of many SNPs could lead to over-specification and result in a score that performs poorly in other cohorts. Furthermore, in addition to non-modifiable factors, PHS and PRS could both be enriched with the introduction of lifestyle and environmental factors, known to be associated with the disease. Moving forward, we can anticipate that combining genetic, lifestyle and environmental components will facilitate the development of more refined and personalised risk profiles that will become relevant in clinical settings.

Availability of data and materials

All data and samples used in this study are derived from the Australian Imaging, Biomarkers and Lifestyle (AIBL). All AIBL data, and that specific to this study, are publicly accessible to all interested parties through an Expression of Interest procedure and is governed by the AIBL Data Use Agreement. For more information, please visit https://aibl.csiro.au/awd/.

References

Corder EH, Saunders AM, Strittmatter WJ, Schmechel DE, Gaskell PC, Small GW, et al. Gene dose of apolipoprotein E type 4 allele and the risk of Alzheimer’s disease in late onset families. Science. 1993;261(5123):921–3.

Zhang Q, Sidorenko J, Couvy-Duchesne B, Marioni RE, Wright MJ, Goate AM, et al. Risk prediction of late-onset Alzheimer’s disease implies an oligogenic architecture. Nat Commun. 2020;11:4799.

Hindorff LA, Sethupathy P, Junkins HA, Ramos EM, Mehta JP, Collins FS, et al. Potential etiologic and functional implications of genome-wide association loci for human diseases and traits. PNAS. 2009;106(23):9362–7.

Lambert J-C, Ibrahim-Verbaas CA, Harold D, Naj AC, Sims R, Bellenguez C, et al. Meta-analysis of 74,046 individuals identifies 11 new susceptibility loci for Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Genet. 2013;45(12):1452–8.

Chatterjee N, Shi J, García-Closas M. Developing and evaluating polygenic risk prediction models for stratified disease prevention. Nat Rev Genet. 2016;17(7):392–406.

Choi SW, Mak TS-H, O’Reilly PF. Tutorial: a guide to performing polygenic risk score analyses. Nat Protoc. 2020;15(9):2759–72.

Escott-Price V, Sims R, Bannister C, Harold D, Vronskaya M, Majounie E, et al. Common polygenic variation enhances risk prediction for Alzheimer’s disease. Brain. 2015;138(12):3673–84.

Escott-Price V, Shoai M, Pither R, Williams J, Hardy J. Polygenic score prediction captures nearly all common genetic risk for Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2017;49:214.e7–214.e11.

Desikan RS, Fan CC, Wang Y, Schork AJ, Cabral HJ, Cupples LA, et al. Genetic assessment of age-associated Alzheimer disease risk: Development and validation of a polygenic hazard score. PLoS Med. 2017;14(3):e1002258.

Fowler C, Rainey-Smith SR, Bird S, Bomke J, Bourgeat P, Brown BM, et al. Fifteen Years of the Australian Imaging, Biomarkers and Lifestyle (AIBL) Study: Progress and Observations from 2,359 Older Adults Spanning the Spectrum from Cognitive Normality to Alzheimer’s Disease. J Alzheimer’s Dis Rep. 2021;5(1):443–68.

Winblad B, Palmer K, Kivipelto M, Jelic V, Fratiglioni L, Wahlund L-O, et al. Mild cognitive impairment--beyond controversies, towards a consensus: report of the International Working Group on Mild Cognitive Impairment. J Intern Med. 2004;256(3):240–6.

McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, Katzman R, Price D, Stadlan EM. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurology. 1984;34(7):939–44.

Doré V, Bourgeat P, Villemagne VL, Fripp J, Macaulay L, Masters CL, et al. CapAIBL: Automated Reporting of Cortical PET Quantification Without Need of MRI on Brain Surface Using a Patch-Based Method. In: Wu G, Coupé P, Zhan Y, Munsell BC, Rueckert D, editors. Patch-Based Techniques in Medical Imaging: Springer International Publishing; 2016. p. 109–16. (Lecture Notes in Computer Science).

Bourgeat P, Doré V, Fripp J, Ames D, Masters CL, Salvado O, et al. Implementing the centiloid transformation for 11C-PiB and β-amyloid 18F-PET tracers using CapAIBL. Neuroimage. 2018;183:387–93.

Klunk WE, Koeppe RA, Price JC, Benzinger T, Devous MD, Jagust W, et al. The Centiloid Project: Standardizing Quantitative Amyloid Plaque Estimation by PET. Alzheimers Dement. 2015;11(1):1–15.e4.

Zhou L, Salvado O, Doré V, Bourgeat P, Raniga P, Macaulay SL, et al. MR-Less Surface-Based Amyloid Assessment Based on 11C PiB PET. PLoS One. 2014;9(1):e84777.

Budgeon CA, Murray K, Turlach BA, Baker S, Villemagne VL, Burnham SC, et al. Constructing longitudinal disease progression curves using sparse, short-term individual data with an application to Alzheimer’s disease. Stat Med. 2017;36(17):2720–34.

Villemagne VL, Burnham S, Bourgeat P, Brown B, Ellis KA, Salvado O, et al. Amyloid β deposition, neurodegeneration, and cognitive decline in sporadic Alzheimer’s disease: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Neurol. 2013;12(4):357–67.

Tan CH, Bonham LW, Fan CC, Mormino EC, Sugrue LP, Broce IJ, et al. Polygenic hazard score, amyloid deposition and Alzheimer’s neurodegeneration. Brain. 2019;142(2):460–70.

Desikan RS, Ségonne F, Fischl B, Quinn BT, Dickerson BC, Blacker D, et al. An automated labeling system for subdividing the human cerebral cortex on MRI scans into gyral based regions of interest. Neuroimage. 2006;31(3):968–80.

Aiken LS, West SG, Reno RR. Multiple regression: testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park: Sage Publications; 1991. p. 212.

Burnham SC, Laws SM, Budgeon CA, Doré V, Porter T, Bourgeat P, et al. Impact of APOE-ε4 carriage on the onset and rates of neocortical Aβ-amyloid deposition. Neurobiol Aging. 2020;95:46–55.

Ellis KA, Bush AI, Darby D, Fazio DD, Foster J, Hudson P, et al. The Australian Imaging, Biomarkers and Lifestyle (AIBL) study of aging: methodology and baseline characteristics of 1112 individuals recruited for a longitudinal study of Alzheimer’s disease. Int Psychogeriatr. 2009;21(4):672–87.

Lupton MK, Strike L, Hansell NK, Wen W, Mather KA, Armstrong NJ, et al. The effect of increased genetic risk for Alzheimer’s disease on hippocampal and amygdala volume. Neurobiol Aging. 2016;40:68–77.

Acknowledgements

We thank all the investigators within the AIBL who contributed to the design and implementation of the resource and/or provided data but did not actively participate in the development, analysis, interpretation or writing of this current study. A complete listing of AIBL investigators can be found at https://aibl.csiro.au/about/aibl-research-team/. We would like to acknowledge Chun Chieh Fan for the assistance provided in the calculation of the PHS and acknowledge the work of the late Rahul Desikan and his co-workers for their significant contributions to increasing our understanding of the polygenic nature of Alzheimer’s Disease risk.

Funding

Funding for the AIBL study was provided in part by the study partners [Commonwealth Scientific Industrial and research Organisation (CSIRO), Edith Cowan University (ECU), Austin Health, CogState Ltd.]. The AIBL study has also received support from the National Health and Medical Research Council (NHMRC). Data used in preparation of this article was obtained from the AIBL [10] (https://aibl.csiro.au/). Funding for this research was also supported through a NHMRC grant (GNT1161706) awarded to S.M.L.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.V wrote the initial manuscript and performed the data analysis. T.P., L.M. contributed to the acquisition of genetic data. VD, VV, PB contributed to acquisition of imaging data and revising the manuscript. S.B. and T.C. contributed to the acquisition of age of onset data. J.D. and M.V. verified the analytical methods. S.L. devised the project and the main conceptual ideas, supervised the findings of this work and obtained funding. M.V., T.P., J.D. S.L. discussed the results and contributed to the manuscript. J.F., C.M. and C.R. contributed to AIBL study design and obtaining AIBL funding. All authors reviewed and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethics approval for the AIBL study and all experimental protocols was provided by Austin Health, St Vincent’s Health, Hollywood Private Hospital and Edith Cowan University. All experiments and methods were carried out in accordance with approved guidelines and regulations and all volunteers gave written informed consent before participating in the study.

Consent for publication

NA.

Competing interests

The authors declare that there is no competing interest in relation to work described in this study.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Data used in the preparation of this article was obtained from the Australian Imaging Biomarkers and Lifestyle study (AIBL).

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Supplementary Figure 1

. A, Distribution of PHS in the whole cohort. High and low PHS were defined as 1 SD above the mean and 1 SD below the mean respectively. B, Distribution of PHS stratified by number of APOE e4 alleles (0 = e2/e3, e2/e2, e3/e3; 1 = e4/e3, e4/e2 ; 2 = e4/e4).

Additional file 2: Supplementary Figure

2. PHS is associated with local Ab and cortical atrophy in non-ε4 carrier. Beta estimates of (A) the associations of PHS with cross-sectional voxel-wise Centiloid and (B) Longitudinal change in regional cortical volumes in non-ε4 carrier individuals.

Additional file 3: Supplementary Table 1

. Beta estimates of the interaction between PHS and time on longitudinal regional cortical volume change controlling for APOE status.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Vacher, M., Doré, V., Porter, T. et al. Assessment of a polygenic hazard score for the onset of pre-clinical Alzheimer’s disease. BMC Genomics 23, 401 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-022-08617-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12864-022-08617-2