Abstract

Background

While a considerable amount of research has explored plant community composition in primary successional systems, little is known about the microbial communities inhabiting these pioneer plant species. Fungal endophytes are ubiquitous within plants, and may play major roles in early successional ecosystems. Specifically, endophytes have been shown to affect successional processes, as well as alter host stress tolerance and litter decomposition dynamics—both of which are important components in harsh environments where soil organic matter is still scarce.

Results

To determine possible contributions of fungal endophytes to plant colonization patterns, we surveyed six of the most common woody species on the Pumice Plain of Mount St. Helens (WA, USA; Lawetlat'la in the Cowlitz language; created during the 1980 eruption)—a model primary successional ecosystem—and found low colonization rates (< 15%), low species richness, and low diversity. Furthermore, while endophyte community composition did differ among woody species, we found only marginal evidence of temporal changes in community composition over a single field season (July–September).

Conclusions

Our results indicate that even after a post-eruption period of 40 years, foliar endophyte communities still seem to be in the early stages of community development, and that the dominant pioneer riparian species Sitka alder (Alnus viridis ssp. sinuata) and Sitka willow (Salix sitchensis) may be serving as important microbial reservoirs for incoming plant colonizers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The Pumice Plain of Mount St. Helens (Lawetlat'la in the Cowlitz language) has served as a model for studying primary succession since its catastrophic eruption in 1980 [1, 2]. Old growth forest was obliterated and replaced with a 20 km2 layer of sterile pumice up to 200 m deep, creating a landscape that resembled the surface of the moon. A few years following the eruption, del Moral [3] observed just 3% vegetation cover on an exposed ridge affected by the pyroclastic flows, and by 1995, Lawrence and Ripple [4] estimated that vegetation cover on the Pumice Plain remained at 0–10% cover, with some areas of 11–20% cover. Even after 40 years following the eruption, the area remains largely barren—especially of woody species—except for sparse, stunted conifers and thickets of shrubs along riparian corridors [2, 5]. While there have been many studies of primary succession of vascular plants [6,7,8,9] and even their associated mycorrhizae [10,11,12], virtually no information exists on the diversity, temporal variation, and turnover of foliar endophyte communities colonizing these plants.

Endophytes are ubiquitous plant symbionts most simply defined as microbes spending the majority of their lifecycles living asymptomatically within host plant tissues [13, 14]. Fungal endophytes specifically have been most extensively studied in agricultural grass hosts, but have also been reported in important forest trees such as red alder [15, 16], maple [17, 18], oak [19, 20], and various conifers [21, 22]. Like other types of symbionts—e.g. root-associated mycorrhizal fungi or nitrogen-fixing Frankia and rhizobia—foliar endophytes can play critical roles in host plant fitness by affecting disease or pest resistance [23], drought tolerance [24], and overall competitive ability [25]. In addition to direct effects on host plants, foliar endophytes are also capable of altering plant community assembly [26, 27] and afterlife effects (reviewed in Wolfe and Ballhorn [28]) that can eventually affect ecosystem processes and nutrient cycling. These host–endophyte dynamics are especially important to consider in early successional ecosystems where effects may be disproportionate due to harsh environmental conditions, limited propagules, and sparse host plant communities.

Primary successional ecosystems are characterized by barren substrate produced by natural disasters or climate change, such as volcanic eruptions or receding glaciers [29, 30]. These ecosystems are frequently nutrient-limited, and may take centuries to develop into forests [31]. In these sparse environments, fewer propagules exist for microbial colonization of pioneering plant species [32]. Since microbial communities are critical to ecosystem function, a slow development thereof has significant implications for succession [33]. Dispersal limitation and environmental filters further reduce the pool of successful colonists in successional landscapes [34]. However, community assembly rules suggest that priority effects may alter successional trajectories of some species, which may contribute to changes in other communities or biogeochemical processes within an ecosystem. In a culture-based experiment that consisted of inoculating wooden disks with fungi and varying the initial colonizers to study how arrival order affected community composition and decomposition rates, Fukami et al. [35] emphasized the importance of assembly history in connecting community and ecosystem ecology. Given that the establishment and prevalence of plant–endophyte interactions are still widely unknown in new, anthropogenically-undisturbed ecosystems, we surveyed six major woody species on the Pumice Plain of Mount St. Helens and characterized the culturable fungal endophyte communities over a 3-month field season to answer the following questions: 1. How diverse are culturable foliar endophyte communities in this early successional ecosystem? 2. Do these communities exhibit host specificity? and 3. Do these endophyte communities show temporal variation over a growing season?

Results

We isolated foliar fungal endophytes from the six most abundant woody species on the Pumice Plain of Mount St. Helens throughout the 2017 summer field season, and found species-specific endophyte community composition despite overall low colonization rates. A total of 40 OTUs were isolated from 113 leaf samples (14.1% of total n = 801 leaves; 19.4% of surveyed trees), representing 18 families and 23 genera. The highest number of OTUs were isolated from Sitka alder (22), followed by Sitka willow (14), cottonwood (10), Douglas fir (11), western hemlock (7), and noble fir (1). All of the OTUs belonged to Ascomycota except for one member of Basidiomycota, and included a total of four classes: Dothidiomycetes (16 OTUs), Pezizomycetes (13 OTUs), Sordariomycetes (9 OTUs), Eurotiomycetes (1 OTU), and Agaricomycetes (1 OTU). Frequencies of isolation ranged from 45.13% (OTU01; Arthrinium sp.) to 0.885% for singletons (18 OTUs), averaging 3.12 ± 7.12% (mean ± SD) over all cultured OTUs. As anticipated given the limitations of culture-based techniques, the species accumulation curve showed that sampling more leaves would have revealed additional taxa, especially for conifer host species (Fig. 1).

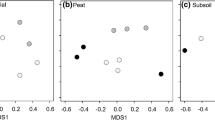

While the fungal endophyte community composition differed significantly among species (PERMANOVA, F5,112 = 1.7781, p = 0.004; Fig. 2), it did not vary over time (PERMANOVA, p = 0.087; Fig. 3A), and subsequently there was no significant interaction between host species and time (Additional file 1: Figure S1). Tree type (i.e. conifer vs. deciduous) however did have a significant effect on community composition (PERMANOVA, F1,112 = 1.9764, p = 0.035; Fig. 3B). The endophyte community composition also varied significantly between deciduous host species (PERMANOVA, F2,89 = 2.4337, p = 0.002), but only marginally over time (PERMANOVA, F2,89 = 1.4523, p = 0.099; Additional file 1: Figure S2). Overall OTU richness (1.248 ± 0.492) and Shannon diversity indices (0.166 ± 0.311) were low, and no significant differences existed either among species or over time for either the entire community or the deciduous subset. Over three-quarters of leaves yielded a single OTU, while the remaining leaves had at least two, including one cottonwood leaf (Site 62, harvested in September) that had the highest species richness of 4.

Only OTU16 (Tricharina praecox) was significantly associated with a particular host plant species (cottonwood; indicator species analysis, IV = 0.447, p = 0.040), while OTU11 (unclassified Pleosporales sp.; IV = 0.295, p = 0.045) and OTU12 (Sporormiella intermedia; IV = 0.347, p = 0.035) were associated with conifer hosts. OTU04 (Melanconis italica) was almost exclusively isolated from samples collected in September (IV = 0.357, p = 0.045). Within the alder-willow subset, OTU03 (Pseudoplectania episphagnum) and OTU06 (Pyronemataceae sp.) were associated with Sitka willow as a host species (IV = 0.459, p = 0.005; IV = 0.324, p = 0.035, respectively), while OTU04 (Melanconis italica) was associated with Sitka alder hosts (IV = 0.463, p = 0.010).

Discussion

Our study revealed that after nearly four decades, culturable foliar fungal endophytes have been slow to colonize major woody host species on the early primary successional Pumice Plain of Mount St. Helens. In contrast, vegetation communities stabilized on the nearby Plains of Abraham after just two decades [36]. Additionally, in red alder trees in the Portland Metro area and Tillamook State Forest (both in Oregon), we found significantly higher numbers of OTUs and a smaller proportion of singletons from over 95% of leaves sampled, compared to less than 15% of leaves sampled at the Mount St. Helens Pumice Plain [15]. In conifers throughout the Pacific Northwest, Carroll and Carroll [21] found that the percentage of infected needles ranged from 20–100% depending on the conifer host species, while we observed an overall colonization rate of 14.1% on the Pumice Plain. This colonization rate is consistent with the colonization rate in needles of Pinus taeda seedlings (14.0%; [37]). Overall, on the Pumice Plain we observed colonization rates that were considerably lower than those that have been recorded for both deciduous and coniferous trees in the region using similar or identical culture-based methods [15, 16, 21].

The low richness and diversity of the endophyte community are an order of magnitude smaller than values measured in nearby non-successional (i.e. significantly later stage) sites [15], suggesting there could be a sizeable lag between the establishment of host plants and eventual foliar colonists on the Pumice Plain. Similar patterns have been observed in root-associated symbionts (i.e. mycorrhizae, dark septate endophytes) at the forefront of a receding glacier [12, 38], as well as in mycorrhizal and Alnus-associated Frankia communities also on the Pumice Plain [39, 40], although soil microbial communities appear to be structured by different factors during early succession [41]. While plant community richness may have peaked in some areas of the Pumice Plain [42], plant cover is largely patchy and separated by stretches with inhospitable conditions. Conifers are especially sparse on the Pumice Plain, while substantial thickets of Sitka willow and alder are present along riparian corridors and within seeps, and clusters of the shrubs are interspersed throughout the upland areas. Propagules of endophytes may be present but unable to effectively disperse or establish, as was the case for early mycorrhizae just a few years following the eruption [40]. Consequently, given that the presence and proximity of host plants were important factors for foliar endophyte colonization of beachgrasses in coastal sand dunes [13], the infrequent distribution of host plants on the Pumice Plain compared to surrounding, less impacted areas likely contributed to the poverty of the culturable endophyte community. Additionally, microclimatic conditions and local soil chemical features play particularly significant roles in determining plant community establishment and composition on the Pumice Plain [42,43,44], and may act as additional filters for endophyte colonization.

Endophyte community compositions were host-specific and included several generalist taxa—a pattern consistent with other studies on oak, cypress, ash, and maple [45, 46]. The most commonly isolated OTU (Arthrinium sp.) was found in all six species, and members of the genus have been previously reported in the leaves and stems of Alnus sp. [47], Salix sp. [48], and Populus sp. [49], as well as in a variety of both temperate and tropical plants [50,51,52,53]. To our knowledge, we are the first to report Arthrinium sp. in Douglas fir, western hemlock, and noble fir, and Pseudoplectania sp. in Sitka willow. Notably, Arthrinium sp. was isolated from Salix alba infested with the woodwasp Xiphydria that disperses its fungal symbionts between trees [48], and both willow and cottonwood shrubs are affected by stem-boring, poplar-willow weevils on the Pumice Plain [54]. A number of taxa isolated from these particular weevils can also occur as generalist endophytes [55], and demonstrate a possible dispersal vector that should be further investigated with molecular techniques.

Surprisingly, we did not find a significant temporal effect on foliar endophyte community composition throughout the vegetation period, contrary to other studies [56, 57], including one that was conducted in the same geographical region [58]. We did obtain nearly four times as many cultures from deciduous compared to conifer hosts—reflecting the significant effect of tree type on community composition—but even the deciduous community that excluded conifers only marginally varied over the 3-month field season. This pattern was largely driven by the presence of OTU01 (Arthrinium sp.) in nearly every harvest for each host species and a considerable number of singletons. The three most abundant genera that were isolated are broadly classified as either saprotrophs or pathogens in the FUNGuild database [59]. Initial colonists also have significant priority effects on the trajectories of endophyte community composition [60], and may explain some of the shared colonization patterns on the Pumice Plain. However, culture-based methods are inherently more biased than culture-independent methods due to variation in surface-sterilization effectiveness, media used, and the low percentage of microbes that are capable of growing in culture. Consequently, overrepresentation of fast-growing, possibly aggressive competitors should not be unexpected, especially in conjunction with culture-based techniques.

Host plant age can also be an important factor determining endophyte presence and diversity [37]. The trees sampled in this study ranged between 1 and 3 m in height and likely were younger than trees sampled in comparable studies, but the true variation in ages and any effects it may have had on our results are unknown [15, 21, 37, 61]. In addition, leaf age can significantly affect the foliar endophyte community [62, 63], and may have influenced the taxa that we were able to isolate, at least in regard to the conifer hosts. Needles in particular were sampled near the ends of branches, and new growth that had not been colonized yet may have been overrepresented. Carroll and Carroll [21] also cite high elevation as a factor in affecting the quality of a plant host—particularly for Tsuga heterophylla, also sampled here—which may also apply to our field site (~ 1000 m a.s.l.). Still, the strikingly low diversity of endophytes at our study site across multiple tree species suggests slow succession of these microbial foliar communities.

Conclusions

Our findings are an important first step in further characterizing the plant-associated microbial community of the Pumice Plain, a particularly well-studied primary model ecosystem, which has so far only included studies of mycorrhizae [10, 40] and Frankia symbionts [39, 64]. We found that culturable endophyte communities are dominated by saprotrophs and pathogens and overall show high species-specificity, although there are obvious biases and limitations of both culture-based techniques and Sanger sequencing. The endophyte communities we identified exhibited remarkably little diversity—in particular in comparison to relatively closely located control sites—and no statistically significant temporal variation, which may be a function of both uneven sampling depth due to limitations in the field and culture-based methods. Regardless, dominant pioneer riparian species like Sitka willow and alder are likely serving as important microbial reservoirs and facilitators for subsequent plant colonization. Primary successional systems like the Pumice Plain are unique models that allow critical insight into how communities and ecosystems reestablish after catastrophic destruction. While mock communities and experimental manipulation can help clarify the underlying mechanisms within, and effects of, plant–microbe interactions, the well-documented eruption and initial stages of recovery on Mount St. Helens are especially crucial for observing the way that plant–microbe interactions develop after catastrophic events.

Methods

Between July and September 2017, we sampled six common woody species found on the Pumice Plain of Mount St. Helens, WA [65]: Sitka alder, Sitka willow, cottonwood, Douglas fir, noble fir, and western hemlock (Table 1). Sites were identified by traversing previously-established horizontal transects [66, 67] and collecting GPS coordinates for over 300 trees. Using GPS coordinates and the R package Imap, trees less than 100 m from one another were clustered into sites; however, any prospective sites with fewer than four of the six species of interest present were excluded from final consideration. Twenty sampling sites (n = 371 trees) were identified based on the number of species, whether there were more than two individuals of a given species present (maximum of 3 were sampled per species per site), and if the sites were reasonably accessible (Fig. 4). Except in the case of no remaining leaves, the same trees were sampled every 30 days during the 3-month field season (July–September). Either three deciduous leaves or 5–10 cm branch pieces (conifers) were randomly collected from each tree using gloves sterilized with 95% ethanol. Samples were collected and transported to the lab in a cooler (< 15 ℃) on the same day, which contributed to practical limitations for sample collection and the effective sample size. Leaves were stored at 4 ℃ for less than 48 h before surface-sterilization. The following minor modifications were made to the methods detailed in Wolfe et al. [15] to accommodate bulk surface-sterilization of leaves: custom sheets of mesh sleeves were constructed from window-screen and sterilized prior to use, and then used to transfer leaves between washes in sterilized polypropylene bins. Sheets of leaves were air-dried in a laminar-flow hood and then processed aseptically onto malt extract agar (MEA) plates. We verified the efficacy of these modifications by re-sampling previously studied red alder (Alnus rubra) trees in the Portland Metropolitan area and finding similar colonization rates as Wolfe et al. [15].

Plates were checked every 3 days for fungal growth, and any new isolates were transferred to new MEA plates until axenic. While isolates were initially differentiated by morphology, all new growth was transferred to new MEA plates for verification through Sanger sequencing. Fungal isolates from MEA plates were processed with the Sigma Tissue Extract-N-Amp Kit (St. Louis, MO). We used primers ITS1F and ITS4 to amplify DNA with the following thermocycler settings: 34 cycles of 94 ℃, 50 ℃, and 72 ℃ for 1 min each, followed by a final extension at 72 ℃ for 10 min. Products were checked with gel electrophoresis before being sent to Function Biosciences (Milwaukee, WI) for Sanger sequencing. Raw sequencing data were manually inspected and cleaned in Geneious 10.2.3. The output was then aligned with MAFFT on XSEDE v7.427 [68, 69] and imported into mothur v.1.42.3 [70] to generate both putative taxonomic assignments through UNITE [71] and operational taxonomic unit (OTU) tables (sequence submission pending at GenBank). OTUs were clustered at 99% similarity [72] using the furthest-neighbor algorithm [61].

Data were analyzed with R v. 3.6.3 with vegan, car, and indicspecies [73, 74], and abundance figures were generated with phyloseq [75], while the map in Fig. 4 was created with ggmap [76]. Differences in community compositions were first tested for homogenous dispersion within and among groups (betadisper in vegan; Bray–Curtis), and then compared with permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA; adonis2; Bray–Curtis distance, and 999 permutations) for all host species, tree type (conifer vs. deciduous), and collection month (July, August, or September). Since over three-quarters of the isolates came from deciduous hosts, we created a subset of the community for those species (alder, willow, and cottonwood), and used PERMANOVA tests to compare differences in species composition and collection month after verifying dispersion was homogeneous within and among all groupings (i.e., by species or over time). Non-metric multidimensional scaling ordinations (Bray–Curtis distances, k = 3 determined by screeplot) were used to visualize community compositions. Richness and Shannon diversity indices were calculated using vegan. If assumptions could not be met, nonparametric Kruskal–Wallis tests were used instead.

Availability of data and materials

The raw data are available in the following GitHub repository: https://github.com/emwolfe/MSH_endophytes.

Abbreviations

- A. procera/ABPR:

-

Noble fir

- A. viridis or A. viridis ssp. sinuata/ALVI:

-

Sitka alder

- MEA:

-

Malt extract agar

- OUT:

-

Operational taxonomic unit

- P. menziesii/PSME:

-

Douglas fir

- PERMANOVA:

-

Permutational multivariate analysis of variance

- S. sitchensis/SASI:

-

Sitka willow

- T. heterophylla/TSHE:

-

Western hemlock

References

Wood DM, del Moral R. Mechanisms of early primary succession in subalpine habitats on Mount St. Helens. Ecology. 1987;68:780–90. https://doi.org/10.2307/1938349.

del Moral R. Plant succession on pumice at Mount St Helens, Washington. Am Midl Nat. 1999;141:101–14.

del Moral R. Initial recovery of subalpine vegetation on Mount St. Helens, Washington. Am Midl Nat. 1983;109:72. https://doi.org/10.2307/2425517.

Lawrence RL, Ripple WJ. Calculating change curves for multitemporal satellite imagery Mount St. Helens 1980–1995. Remote Sens Environ. 1999;67:309–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0034-4257(98)00092-3.

LeRoy CJ, Ramstack Hobbs JM, Claeson SM, Moffett J, Garthwaite I, Criss N, et al. Plant sex influences aquatic–terrestrial interactions. Ecosphere. 2020;11: e02994. https://doi.org/10.1002/ecs2.2994.

Chapin FS, Walker LR, Fastie CL, Sharman LC. Mechanisms of primary succession following deglaciation at Glacier Bay. Alaska Ecol Monogr. 1994;64:149–75.

Grishin SY, Moral R, Krestov PV, Verkholat VP. Succession following the catastrophic eruption of Ksudach volcano (Kamchatka, 1907). Vegetatio. 1996;127:129–53.

del Moral R. Early succession on lahars spawned by Mount St. Helens. Am J Bot. 1998;85:820–8.

Titus JH, Moore S, Arnot M, Titus PJ. Inventory of the vascular flora of the blast zone, Mount St. Helens, Washington. Madroño. 1998;45:146–61. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41425256.

Titus JH, del Moral R. The role of mycorrhizal fungi and microsites in primary succession on Mount St. Helens. Am J Bot. 1998;85:370–5.

Titus JH, Tsuyuzaki S. Arbuscular mycorrhizal distribution in relation to microsites on recent volcanic substrates of Mt Koma, Hokkaido, Japan. Mycorrhiza. 2002;12:271–5.

Cázares E, Trappe JM, Jumpponen A. Mycorrhiza-plant colonization patterns on a subalpine glacier forefront as a model system of primary succession. Mycorrhiza. 2005;15:405–16.

David AS, Seabloom EW, May G. Plant host species and geographic distance affect the structure of aboveground fungal symbiont communities, and environmental filtering affects belowground communities in a coastal dune ecosystem. Microb Ecol. 2016;71:912–26. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00248-015-0712-6.

Saikkonen K, Wäli P, Helander M, Faeth SH. Evolution of endophyte–plant symbioses. Trends Plant Sci. 2004;9:275–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.TPLANTS.2004.04.005.

Wolfe ER, Kautz S, Singleton SL, Ballhorn DJ. Differences in foliar endophyte communities of red alder (Alnus rubra) exposed to varying air pollutant levels. Botany. 2018;96:825–35. https://doi.org/10.1139/cjb-2018-0085.

Sieber TN, Sieber-Canavesi F, Dorworth CE. Endophytic fungi of red alder (Alnus rubra) leaves and twigs in British Columbia. Can J Bot. 1991;69:407–11.

Grimmett IJ, Smith KA, Bärlocher F. Tar-spot infection delays fungal colonization and decomposition of maple leaves. Freshw Sci. 2012;31:1088–95. https://doi.org/10.1899/12-034.1.

Wolfe ER, Younginger BS, LeRoy CJ. Fungal endophyte-infected leaf litter alters in-stream microbial communities and negatively influences aquatic fungal sporulation. Oikos. 2019;128:405–15. https://doi.org/10.1111/oik.05619.

Szink I, Davis EL, Ricks KD, Koide RT. New evidence for broad trophic status of leaf endophytic fungi of Quercus gambelii. Fungal Ecol. 2016;22:2–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.FUNECO.2016.04.003.

Jumpponen A, Jones KL. Seasonally dynamic fungal communities in the Quercus macrocarpa phyllosphere differ between urban and nonurban environments. New Phytol. 2010;186:496–513. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8137.2010.03197.x.

Carroll GC, Carroll FE. Studies on the incidence of coniferous needle endophytes in the Pacific Northwest. Can J Bot. 1978;56:3034–43. https://doi.org/10.1139/b78-367.

U’Ren JM, Arnold AE. Diversity, taxonomic composition, and functional aspects of fungal communities in living, senesced, and fallen leaves at five sites across North America. PeerJ. 2016;4: e2768. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.2768.

Waller F, Achatz B, Baltruschat H, Fodor J, Becker K, Fischer M, et al. The endophytic fungus Piriformospora indica reprograms barley to salt-stress tolerance, disease resistance, and higher yield. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:13386–91. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0504423102.

Khan Z, Rho H, Firrincieli A, Hung SH, Luna V, Masciarelli O, et al. Growth enhancement and drought tolerance of hybrid poplar upon inoculation with endophyte consortia. Curr Plant Biol. 2016;6:38–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CPB.2016.08.001.

Aschehoug ET, Metlen KL, Callaway RM, Newcombe G. Fungal endophytes directly increase the competitive effects of an invasive forb. Ecology. 2012;93:3–8. https://doi.org/10.1890/11-1347.1.

Rudgers JA, Holah J, Orr SP, Clay K, Orr P. Forest succession suppressed by an introduced plant-fungal symbiosis. Ecol Soc Am. 2007;88:18–25.

Rudgers JA, Clay K. Endophyte symbiosis with tall fescue: how strong are the impacts on communities and ecosystems? Fungal Biol Rev. 2007;21:107–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fbr.2007.05.002.

Wolfe ER, Ballhorn DJ. Do foliar endophytes matter in litter decomposition? Microorganisms. 2020;8:446. https://doi.org/10.3390/microorganisms8030446.

del Moral R, Wood DM. Early primary succession on a barren volcanic plain at Mount St. Helens, Washington. Am J Bot. 1993;80:981–91.

Milner AM. Colonization and ecological development of new streams in Glacier Bay National Park. Alaska Freshw Biol. 1987;18:53–70. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2427.1987.tb01295.x.

Lichter J. Primary succession and forest development on coastal Lake Michigan sand dunes. Ecol Monogr. 1998;68:487–510. https://doi.org/10.1890/0012-9615(1998)068[0487:psafdo]2.0.co;2.

Trowbridge J, Jumpponen A. Fungal colonization of shrub willow roots at the forefront of a receding glacier. Mycorrhiza. 2004;14:283–93.

Knelman JE, Legg TM, O’Neill SP, Washenberger CL, González A, Cleveland CC, et al. Bacterial community structure and function change in association with colonizer plants during early primary succession in a glacier forefield. Soil Biol Biochem. 2012;46:172–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.SOILBIO.2011.12.001.

Leibold MA, Holyoak M, Mouquet N, Amarasekare P, Chase JM, Hoopes MF, et al. The metacommunity concept: a framework for multi-scale community ecology. Ecol Lett. 2004;7:601–13. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2004.00608.x.

Fukami T, Dickie IA, Paula Wilkie J, Paulus BC, Park D, Roberts A, et al. Assembly history dictates ecosystem functioning: evidence from wood decomposer communities. Ecol Lett. 2010;13:675–84. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1461-0248.2010.01465.x.

del Moral R, Saura JM, Emenegger JN. Primary succession trajectories on a barren plain, Mount St. Helens, Washington. J Veg Sci. 2010;21:857–67. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1654-1103.2010.01189.x.

Oono R, Lefèvre E, Simha A, Lutzoni F. A comparison of the community diversity of foliar fungal endophytes between seedling and adult loblolly pines (Pinus taeda). Fungal Biol. 2015;119:917–28.

Jumpponen A, Trappe JM, Cázares E. Occurrence of ectomycorrhizal fungi on the forefront of retreating Lyman Glacier (Washington, USA) in relation to time since deglaciation. Mycorrhiza. 2002;12:43–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00572-001-0152-7.

Seeds JD, Bishop JG. Low Frankia inoculation potentials in primary successional sites at Mount St. Helens, Washington, USA. Plant Soil. 2009;323:225–33. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-009-9930-3.

Allen MF, Crisafulli C, Friese CF, Jeakins SL. Re-formation of mycorrhizal symbioses on Mount St Helens, 1980–1990: interactions of rodents and mycorrhizal fungi. Mycol Res. 1992;96:447–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0953-7562(09)81089-7.

Brown SP, Jumpponen A. Contrasting primary successional trajectories of fungi and bacteria in retreating glacier soils. Mol Ecol. 2014;23:481–97. https://doi.org/10.1111/mec.12487.

del Moral R. Increasing deterministic control of primary succession on Mount St. Helens, Washington. J Veg Sci. 2009;20:1145–54.

del Moral R, Thomason LA, Wenke AC, Lozanoff N, Abata MD. Primary succession trajectories on pumice at Mount St. Helens, Washington. J Veg Sci. 2012;23:73–85. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1654-1103.2011.01336.x.

Chang CC, HilleRisLambers J. Trait and phylogenetic patterns reveal deterministic community assembly mechanisms on Mount St. Helens. Plant Ecol. 2019;220:675–98. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11258-019-00944-x.

Matsumura E, Fukuda K. A comparison of fungal endophytic community diversity in tree leaves of rural and urban temperate forests of Kanto district, eastern Japan. Fungal Biol. 2013;117:191–201.

Schlegel M, Queloz V, Sieber TN. The endophytic mycobiome of European ash and Sycamore maple leaves—geographic patterns, host specificity and influence of ash dieback. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:2345. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2018.02345.

Osono T, Masuya H. Endophytic fungi associated with leaves of Betulaceae in Japan. Can J Microbiol. 2012;58:507–15. https://doi.org/10.1139/w2012-018.

Pažoutová S, Šrůtka P, Holuša J, Chudíčková M, Kolařík M. Diversity of xylariaceous symbionts in Xiphydria woodwasps: role of vector and a host tree. Fungal Ecol. 2010;3:392–401.

Hutchison LJ. Wood-inhabiting microfungi isolated from Populus tremuloides from Alberta and northeastern British Columbia. Can J Bot. 1999;77:898–905. https://doi.org/10.1139/b99-053.

Maehara S, Simanjuntak P, Ohashi K, Shibuya H. Composition of endophytic fungi living in Cinchona ledgeriana (Rubiaceae). J Nat Med. 2010;64:227–30. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11418-009-0380-2.

Larran S, Perelló A, Simón MR, Moreno V. The endophytic fungi from wheat (Triticum aestivum L.). World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2007;23:565–72. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11274-006-9266-6.

Richardson KA, Currah RS. The fungal community associated with the roots of some rainforest epiphytes of Costa Rica. Selbyana. 1995;16:49–73.

Terhonen E, Marco T, Sun H, Jalkanen R, Kasanen R, Vuorinen M, et al. The effect of latitude, season and needle-age on the mycota of Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris) in Finland. Silva Fenn. 2011;45:301–17.

Che-Castaldo C, Crisafulli CM, Bishop JG, Zipkin EF, Fagan WF. Disentangling herbivore impacts in primary succession by refocusing the plant stress and vigor hypotheses on phenology. Ecol Monogr. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1002/ecm.1389.

Kerrigan J, Rogers J. Microfungi Associated With the Wood-Boring Beetles Saperda calcarata (Poplar Borer) and Cryptorhynchus lapathi (Poplar and Willow Borer). Mycotaxon. 2003;86:1–18.

Ek-Ramos MJ, Zhou W, Valencia CU, Antwi JB, Kalns LL, Morgan GD, et al. Spatial and temporal variation in fungal endophyte communities isolated from cultivated cotton (Gossypium hirsutum). PLoS ONE. 2013;8: e66049. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0066049.

Comby M, Lacoste S, Baillieul F, Profizi C, Dupont J. Spatial and temporal variation of cultivable communities of co-occurring endophytes and pathogens in wheat. Front Microbiol. 2016;7:403. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2016.00403.

Younginger BS, Ballhorn DJ. Fungal endophyte communities in the temperate fern Polystichum munitum show early colonization and extensive temporal turnover. Am J Bot. 2017;104:1188–94. https://doi.org/10.3732/ajb.1700149.

Nguyen NH, Song Z, Bates ST, Branco S, Tedersoo L, Menke J, et al. FUNGuild: an open annotation tool for parsing fungal community datasets by ecological guild. Fungal Ecol. 2016;20:241–8.

Leopold DR, Busby PE. Host genotype and colonist arrival order jointly govern plant microbiome composition and function. Curr Biol. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2020.06.011.

Skaltsas DN, Badotti F, Vaz ABM, da Silva FF, Gazis R, Wurdack K, et al. Exploration of stem endophytic communities revealed developmental stage as one of the drivers of fungal endophytic community assemblages in two Amazonian hardwood genera. Sci Rep. 2019;9:1.

Nascimento TL, Oki Y, Lima DMM, Almeida-Cortez JS, Fernandes GW, Souza-Motta CM. Biodiversity of endophytic fungi in different leaf ages of Calotropis procera and their antimicrobial activity. Fungal Ecol. 2015;14:79–86.

Suryanarayanan TS, Thennarasan S. Temporal variation in endophyte assemblages of Plumeria rubra leaves. Fungal Divers. 2004;15:197–204.

Lipus A, Kennedy PG. Frankia assemblages associated with Alnus rubra and Alnus viridis are strongly influenced by host species identity. Int J Plant Sci. 2011;172:403–10. https://doi.org/10.1086/658156.

Claeson SM, LeRoy CJ, Finn DS, Stancheva RH, Wolfe ER. Variation in riparian and stream assemblages across the primary succession landscape of Mount St. Helens, U.S.A. Freshw Biol. 2021;66:1002–17. https://doi.org/10.1111/fwb.13694.

Che-Castaldo C, Crisafulli CM, Bishop JG, Fagan WF. What causes female bias in the secondary sex ratios of the dioecious woody shrub Salix sitchensis colonizing a primary successional landscape? Am J Bot. 2015;102:1309–22. https://doi.org/10.3732/ajb.1500143.

Titus JH, Bishop JG. Propagule limitation and competition with nitrogen fixers limit conifer colonization during primary succession. J Veg Sci. 2014;25:990–1003. https://doi.org/10.1111/jvs.12155.

Katoh K, Toh H. Parallelization of the MAFFT multiple sequence alignment program. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:1899–900. https://doi.org/10.1093/bioinformatics/btq224.

Miller MA, Pfeiffer W, Schwartz T. Creating the CIPRES Science Gateway for inference of large phylogenetic trees. In: 2010 Gateway Computing Environments Workshop (GCE). 2010. p. 1–8.

Schloss PD, Westcott SL, Ryabin T, Hall JR, Hartmann M, Hollister EB, et al. Introducing mothur: open-source, platform-independent, community-supported software for describing and comparing microbial communities. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2009;75:7537–41. https://doi.org/10.1128/AEM.01541-09.

UNITE Community. UNITE mothur release for Fungi 2. 2019.

Vu D, Groenewald M, de Vries M, Gehrmann T, Stielow B, Eberhardt U, et al. Large-scale generation and analysis of filamentous fungal DNA barcodes boosts coverage for kingdom fungi and reveals thresholds for fungal species and higher taxon delimitation. Stud Mycol. 2019;92:135–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.simyco.2018.05.001.

De CM, Legendre P. Associations between species and groups of sites: indices and statistical inference. Ecology. 2009;90:3566–74. https://doi.org/10.1890/08-1823.1.

Oksanen J, Blanchet FG, Friendly M, Kindt R, Legendre P, McGlinn D, et al. vegan: Community Ecology Package. R package version 2.4–3. 2017. https://cran.r-project.org/package=vegan. Accessed 4 Aug 2017.

McMurdie PJ, Holmes S. phyloseq: an R package for reproducible interactive analysis and graphics of microbiome census data. PLoS ONE. 2013;8: e61217. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0061217.

Kahle D, Wickham H. ggmap: Spatial Visualization with ggplot2. R J. 2013;5:144–61. https://journal.r-project.org/archive/2013/RJ-2013-014/index.html. Accessed 4 Aug 2017.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Funding was provided by the National Science Foundation (NSF) to D.J.B. (Grants IOS 1457369 and 1656057), the Puget Sound Mycological Society to E.R.W (Ben Woo Research Grant), and the Northwest Ecological Research Institute (NERI) to E.R.W. (NERI Associate). Funds from the Puget Sound Mycological Society and NERI were used to purchase supplies for field sampling. Funds from NSF were used to purchase sequencing services.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ERW designed the study, collected samples in the field, processed samples, and conducted the analyses. RD and CW assisted in processing samples. ERW, RD, and DJB wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Figure S1.

NMDS ordination of all host species and all harvest dates. Figure S2. NMDS ordination of deciduous hosts only (Sitka alder, Sitka willow, and cottonwood) and all harvest dates.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Wolfe, E.R., Dove, R., Webster, C. et al. Culturable fungal endophyte communities of primary successional plants on Mount St. Helens, WA, USA. BMC Ecol Evo 22, 18 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12862-022-01974-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12862-022-01974-2