Abstract

Background

Thamnophilidae birds are the result of a monophyletic radiation of insectivorous Passeriformes. They are a diverse group of 225 species and 45 genera and occur in lowlands and lower montane forests of Neotropics. Despite the large degree of diversity seen in this family, just four species of Thamnophilidae have been karyotyped with a diploid number ranging from 76 to 82 chromosomes. The karyotypic relationships within and between Thamnophilidae and another Passeriformes therefore remain poorly understood. Recent studies have identified the occurrence of intrachromosomal rearrangements in Passeriformes using in silico data and molecular cytogenetic tools. These results demonstrate that intrachromosomal rearrangements are more common in birds than previously thought and are likely to contribute to speciation events. With this in mind, we investigate the apparently conserved karyotype of Willisornis vidua, the Xingu Scale-backed Antbird, using a combination of molecular cytogenetic techniques including chromosome painting with probes derived from Gallus gallus (chicken) and Burhinus oedicnemus (stone curlew), combined with Bacterial Artificial Chromosome (BAC) probes derived from the same species. The goal was to investigate the occurrence of rearrangements in an apparently conserved karyotype in order to understand the evolutionary history and taxonomy of this species. In total, 78 BAC probes from the Gallus gallus and Taeniopygia guttata (the Zebra Finch) BAC libraries were tested, of which 40 were derived from Gallus gallus macrochromosomes 1–8, and 38 from microchromosomes 9–28.

Results

The karyotype is similar to typical Passeriformes karyotypes, with a diploid number of 2n = 80. Our chromosome painting results show that most of the Gallus gallus chromosomes are conserved, except GGA-1, 2 and 4, with some rearrangements identified among macro- and microchromosomes. BAC mapping revealed many intrachromosomal rearrangements, mainly inversions, when comparing Willisornis vidua karyotype with Gallus gallus, and corroborates the fissions revealed by chromosome painting.

Conclusions

Willisornis vidua presents multiple chromosomal rearrangements despite having a supposed conservative karyotype, demonstrating that our approach using a combination of FISH tools provides a higher resolution than previously obtained by chromosome painting alone. We also show that populations of Willisornis vidua appear conserved from a cytogenetic perspective, despite significant phylogeographic structure.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The Order Passeriformes is one of the most diverse taxa of birds in terms of phenotypic difference and species richness, with around 6000 species. The group also demonstrates a wide variety of morphological adaptations compatible with their eating habits and ecological niches [1]. In Brazil, there are approximately 1900 species of Passeriformes, with 1300 occurring in the Amazon, of which 265 are endemic [2, 3]. This order represents one of the largest adaptive radiations among vertebrates, with representative species in all continents except Antarctica, and with the most diversity found in the tropics [1].

The Thamnophilidae family (typical antbirds), are a widespread radiation of insectivorous Passeriformes birds. They are a monophyletic and diverse group [4] of species and 45 genera with many occurring in upland forests of the Neotropics [5, 6]. In Brazil there are 195 species of Thamnophilidae birds [7], although it is likely that this is an underestimation of true diversity, particularly in the Amazon region, since the Brazilian avifauna is still being sampled [8]. The Thamnophilidae is a polytypic taxon, meaning that they are likely to be many more species of which we are unaware [8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15]. In Brazil as a whole, there have been 31 new species described in the last decade, 15 of which were found in the Amazon region [17].

A useful tool for characterizing bird species, as well as for understanding their evolutionary history and genome organization is through karyotype analysis [18]. Karyotypic studies can be employed for the detection of rearrangements involved in speciation events in evolutionary comparative studies and could be helpful in defining cryptic species without obviously genetic divergence, but with chromosomal differences [18,19,20]. Several evolutionary studies involving karyotypic characters have been conducted (reviewed in Griffin et al. [22] and Kretschmer et al. [18]), but most are focussed on poultry due to the ease of obtaining samples, or on birds that are of significant commercial value, such as the Psittacidae, targets of biopiracy [23].

In the context of chromosome evolution, avian karyotypes are considered stable when compared to other vertebrate groups such as mammals [24]. However, as in any group of organisms, distinct evolutionary variations occur, with some species such as the falcons and parrots presenting greatly rearranged karyotypes [24,25,26]. Avian species, in general have a stable diploid number, where 2n = ~ 80 chromosomes. Despite some species having morphologically similar macrochromosomes, recent studies using chromosome painting, BAC FISH and genome sequencing analyses [25] have shown that some species have a complex pattern of pericentric and paracentric inversions, and many intrachromosomal rearrangements, including micro inversions, fusions and fissions [27,28,29].

There are five published sets of whole chromosome paints in birds: Gallus gallus (Chicken; GGA, 2n = 78, Galliformes) [31], Burhinus oedicnemus (Eurasian Stone Curlew, BOE, 2n = 42, Charadriiformes) [32], two species of Accipitriformes, Leucopternis albicollis (White Hawk, LAL, 2n = 66) [33], and Gyps fulvus (Griffon Vulture, GFU, 2n = 66) [34], and Zenaida auriculata (Eared Dove, ZAU, 2n = 76) [35]. Of these, Gallus gallus is the only species that has its whole genome sequenced [36]. Gallus gallus derived paints have been hybridized to more than 40 bird species from diverse families, providing maps of reliable chromosome homologies (reviewed in [22, 37, 38]. These results suggest that the ancestral karyotype of birds is similar to the Gallus gallus karyotype. Only 21 species of Passeriformes, most belonging to the Sub-Order Oscines, have been investigated by chromosome painting to date [28, 38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46], and only the Wedge-Billed Woodcreeper (Glyphorynchus spirurus) was investigated using Burhinus oedicnemus probes [7]. The phylogenetic relationship among Gallus gallus, zebra finch, Burhinus oedicnemus and the Wedge-Billed Woodcreeper are summarized in Additional file 1 based in Prum et al. [48].

Cytogenetic analysis of birds in Brazil began in the 1960 s with descriptive studies that summarized the karyotypes of about 200 species of birds, representing about 14 % of the country’s bird life at that time [49, 50]. Our cytogenetic understanding of Brazilian avifauna has gradually increased, however finding even the most basic information, such as diploid number and chromosome morphology, can be challenging. Despite there being approximately 200 species in the Thamnophilidae, there is little cytogenetic information available for this family. Just four species of Thamnophilidae have been karyotyped: Pyriglena leucoptera, 2n = 82 [51], Isleria hauxwelli, 2n = 80 [52], Thamnophilus doliatus, 2n = 82 [53], and Dysithamnus mentalis, 2n = 76 [52]. Willisornis vidua, the Xingu Scale-backed Antbird, is an interesting species to be evaluated for their karyotypic evolution as the species is commonly found and widely distributed across the Amazonian region as well as being a polytypic taxon whose subspecies distribution seem to be restricted to boundaries of major rivers in the Amazon basin and plumage differences [14].

Taking these factors into account and given that the identification of chromosomal inversions cannot be visualised using chromosome painting alone, in this study we used a combination of BACs (Bacterial Artificial Chromosomes) and comparative genomic mapping with chromosome paints of Gallus gallus and B. oedicnemus to investigate the occurrence of rearrangements in an apparently conserved karyotype of Willisornis vidua. Our main goal is to use these techniques to better understand the evolutionary history and taxonomy of this species.

Results

Karyotypic description and chromosome painting

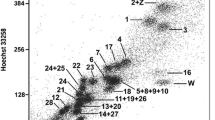

Both Willisornis vidua subspecies have karyotypes indistinguishable from each other with a diploid number of 80, being comprised mostly of acrocentric chromosomes (chromosomes 7 and 9 are metacentric). The Z chromosomes are submetacentric. We have not identified the W chromosome morphology since only male specimens were analysed (Fig. 1).

G-banding karyotype of Willisornis vidua showing the localization of the corresponding probes. Gallus gallus is showed in the left and Burhinus oedicnemus in the right. We follow the nomenclature of Nie et al. [35] for GGA probes

Hybridisation of BOE whole chromosome probes reveal 18 homologous segments on macrochromosomes, including Z, and give 19 signals on microchromosomes on the Willisornis vidua genome (Fig. 2; Table 1). Only five probes (BOE-3, 4, 6, 9 and Z) show preserved synteny in eight chromosomes of WVI. The other probes show two or more hybridisation signals in WVI chromosomes. Hybridisation of GGA whole chromosome probes reveal 14 homologous segments on Willisornis vidua macrochromosomes. The correspondence between BOE, GGA and WVI karyotypes are shown in Table 1. We used data from Nie et al. [32] to identify homologies with GGA.

BAC-FISH

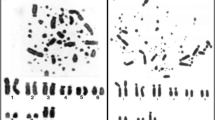

Comparative mapping of BAC clones in Willisornis vidua, using Gallus gallus and Taenopygia guttata BACs, reveal a total of 43 hybridisation signals in the Willisornis vidua genome. We also hybridised the microchromosome BAC clones corresponding to microchromosomes 9–28 in the Gallus gallus (Fig. 3).

Examples of BAC-FISH microchromosomes and Z in the Willisornis vidua karyotype. The micros correspond to CH261-121N21 F with 154H1 Tx (GGA11; left, above), (TGMCBA-375I5 F with CH261-42P16 (TGA17/GGA17; right, above), CH261-115I12 F with TGMCBA-321B13 Tx (GGA13/TGA17; left, below) and TAG-Z TGMCBA-200J22 F with 270I9 Tx (TGAZ; right, below)

Using these 43 BACs, we find 29 intrachromosomal differences between the three species. We also report 14 interchromosomal differences in Willisornis vidua when compared to Taeniopygia guttata and Gallus gallus, using the latter as the reference (Figs. 4 and 5; Table 2). Examples of hybridisation with BAC clones are shown in Figs. 6. We observed extensive homology between GGA and WVI chromosomes. The differences are in Gallus gallus microchromosome 9, which hybridised to WVI macrochromosome 8, and the homolog of micro 17 in GGA and TGA, which hybridised to the distal region of WVI macro 5 (Fig. 3; Table 2).

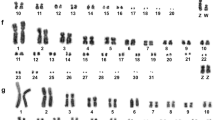

Examples of BAC-FISH macrochromosomes in Willisornis vidua karyotype. The BACs mapped are CH261-1845 (GGA1; left, above), CH261-36B5 F with 58K12 Tx (GGA1; middle, above), CH261-107E2 F with 118M1 Tx (GGA1; right, above), CH261-83O13 (GGA1; left, below), CH261-1203H23 (GGA3; middle, below) and (GCH261-18C6 GA4; right, below). F = Fitc Tx = Texas red

Discussion

Karyotypic variation and chromosome painting

Here we describe, for the first time, cytogenetic analysis of the species Willisornis vidua, collected from the Brazilian Amazon. All subspecies represented here have karyotypes that are similar to the typical avian karyotype with few macrochromosomes, and many microchromosomes.

Chromosome painting with BOE and GGA probes show that most GGA homologues are conserved in toto with the exception of GGA1, 2 and 4. GGA4 is homologous to WVI 4 plus a microchromosome (Fig. 1), as seen in most avian species where the Gallus gallus is a rare exception (see Griffin et al. [22]). On the other hand, the fission of the GGA1 homologue is considered a signature pattern seen in Passeriformes [29, 45, 53,54,55], and the current work found the same arrangement. This fission is not however a synapomorphy confined only to Passeriformes birds, as it is present also in the phylogenetic branch comprising Strigiformes, Passeriformes, Columbiformes and Falconiformes [22, 34, 41, 46, 57]. On the other hand, the fission of GGA1 found by FISH also corroborates the recent hypotheses that Passeriformes and Psittaciformes are sister-groups [18, 48, 58]. Further research, including multicolor banding probe sets and BAC-based multicolor barcoding may test if this hypothesis could be homoplasy or a real signature of this group.

Amazonian rivers are considered geographical barriers for some Amazonian taxa, including birds, thus contributing to speciation events [13, 58,59,60,61]. However, the populations of Willisornis vidua vidua and Willisornis vidua nigrigula sampled herein are separated by the Xingu and Tocantins rivers, and no chromosomal differences were detected, despite a previous study having detected significant genetic variation showing that they are not sister groups [63]. Therefore, here we show that populations of Willisornis vidua appear conserved from a cytogenetic perspective, despite significant phylogeographic structure. Future studies should address whether Willisornis vidua and the remaining species in the genus Willisornis (W. poecilinotus) exhibit any heterotic negative rearrangements in populations with high levels of genetic variation [64, 65]. Both species are in direct contact in the headwaters of the Tapajós and Xingu rivers, where they intergrade, although at a low frequency, and with highly introgressed hybrids showing low fitness coefficients [66].

BAC-FISH

The results presented here show conservative evolutionary stability in microchromosomes when compared with Gallus gallus and Taeniopygia guttata, which is consistent with the genomic and karyotypic conservation in the avian Class [25, 66,67,68]. Exceptions were found with Gallus gallus microchromosome 9, which hybridised to WVI chromosome 8, and the homolog of chromosome 17 in GGA and TGU, which hybridised to the distal region of WVI chromosome 5 (Fig. 3). Our results therefore demonstrate the advantages of using both chromosome painting and BAC-FISH techniques together. By using both, we did not find any evidence of reciprocal translocation, although the data presented here demonstrate that this approach can identify multiple intrachromosomal rearrangements between species (Figs. 4 and 5).

O’Connor et al. [69] compared the Gallus gallus with the Apalone spinifera (Spiny softshell turtle), using chromosome painting and BAC-FISH, and discovered that they too have similar karyotypic patterns, with most chromosomes being precise counterparts of each other. Here, we also used both methods to show the precise definition of homologies between Willisornis vidua, Burhinus oedicnemus and Gallus gallus. This definition, first detected by chromosome painting, was confirmed by BAC-FISH which also revealed the intrachromosomal rearrangements in Willisornis vidua.

We recently proposed the hypothesis that the GGA2 fission is a synapomorphic trait unique to the Furnariidae family as it is present in both Glyphrorynchys spirirus [46] and Synallaxis frontalis [70]. The fission of GGA2 also appears to be present in the karyotype of two species of Formicariidae (sister-group of Furnariidae) [51, 71]. As this rearrangement is ancestral [22], the GGA2 fission was considered to be a homoplasy in Suboscines. However, since several species of this suborder have been analysed by chromosome painting [46, 47, 70] presented here and three species of Thamnophilidae (Ribas et al., data in preparation), together with one species of the Tyrannidae family [47], we suggest that this rearrangement could be a synapomorphic trait in Suboscines. Studies using chromosome-level assemblies are required to test the exact site of the chromosomal breakpoints and confirm this suggestion.

O’Connor et al. [72] found extensive chromosomal rearrangements in the Falco cherrug (saker falcon) when compared with the Gallus gallus. They found 36 intrachromosomal differences and 12 fissions and 5 fusions between the two species. Here, we found 29 intrachromosomal rearrangements, demonstrating that despite having an apparently conserved karyotype the Willisornis vidua genome is highly rearranged intrachromosomally.

The most conserved chromosome found here was the Z. This chromosome showed the same pattern as the Gallus gallus Z when compared with Taeniopygia guttata probes (Figs. 3 and 5). The Z conservation was expected since this chromosome showed uniform painting pattern with Gallus gallus painting probes [18, 37, 46] and seems conserved for the last < 80 million years of bird evolution, reflecting the remarkable stability of the avian karyotype. The Z chromosome demonstrates variable morphology among the Thamnophilidae birds when compared with other species in this family (data in preparation), being acrocentric in Phlegopsis, Isleria and Myrmotherula, submetacentric in Thamnophilus, Pyriglena and Willisornis vidua, and metacentric in Thamnomanes. Chromosomal variations in the Z chromosome are attributed to pericentric inversions and/or centromeric repositioning. In an evolutionary context, some rearrangements in the Z found here and shared with these species suggest a common ancestral.

Besides the high diploid number, we did not find any evidence of microchromosome fission in Willisornis vidua. Comparison of the Willisornis vidua karyotype with the PAK suggests that the 2n = 80 is the result of macrochromosome fission, and that the ancestral microchromosome pattern is consistent with that found in Passeriformes and many other orders [69]. Other species of the Thamnophilidae family need to be analysed to test the hypothesis raised here.

Conclusions

We describe, for the first time, the Willisornis vidua karyotype and its chromosomal homology map with Gallus gallus and stone curlew using chromosome painting probes which reveals an apparently conserved karyotype. We also suggest that based on the data presented here and in previous studies, the GGA2 split is a synapomorphic trait in the Suboscines suborder, given that it was found in the Tyrannidae, Furnariidae and Thamnophilidae families.

We also found a series of new intrachromosomal rearrangements in these species when compared to the Gallus gallus and Taeniopygia guttata genomes (using BAC probes) that are beyond the resolution of chromosome painting. Further research comparing additional species and additional orders based on chromosome-level genome mapping will provide greater understanding about the mechanisms and patterns of chromosome rearrangement among these related species, and will provide greater clarity over whether the rearrangements found here could be synapomorphic traits of the Thamnophilidae family or autapomorphies of Willisornis vidua.

Methods

Samples and chromosomal preparation

Three specimens of Willisornis vidua were collected with mist nets from natural populations of the Brazilian Amazon in Belém and Tapajós endemism areas in the municipalities of Belterra (2°24’05’’S/55°04’40’’W), Mocajuba (2°39’53.7’’S/49°35’’18.3’’W) and Santa Bárbara (1°12’14"S/48°17’39"W) in Pará state. The three specimens correspond to two subspecies: Willisornis vidua from Belterra-Pa is Willisornis vidua nigrigula and the two others specimens of Willisornis vidua from Mocajuba-Pa and Santa Barbará-Pa are Willisornis vidua vidua, whose geographic distributions are limited by the Xingu River, a major tributary of the Amazon Rivers and which acts as a geographical barrier between these subspecies. These subspecies were distinguished by their geographic distribution and plumage color [14]. The species sampled are not endangered or protected.

After capture in the field with mist nets, specimens were maintained in the lab with food and water, free from stress, until their necessary euthanasia. At the lab, colchicine treatment was performed according to the weight of the bird and after 30 minutes to 1 hour. The euthanasia was made with intraperitoneal injection of buffered and diluted barbiturates (86 mg/kg) after anaesthesia with ketamine (40 mg/kg), following The American Veterinary Medical Association Guidelines for the Euthanasia of Animals. The bone marrow preparations obtained from the femur were performed according to Garnero and Gunski [73], with modifications.

Voucher specimens were deposited in the bird collection of the Museu Paraense Emilio Goeldi. JCP has a permanent field permit number 13,248 from “Instituto Chico Mendes de Conservação da Biodiversidade”. The Cytogenetics Laboratory from UFPa has a special permit number 19/2003 from the Brazilian Ministry of Environment for samples transport and 52/2003 for using the samples for research.

Determination of the karyotype

To determine diploid numbers and generate karyotypes, fifty metaphase spreads from each bird subspecies were stained with a combination of inverted DAPI pattern (black/white) or G banding. The chromosomes are displayed according to the Taeniopygia guttata karyotype [46]. Measurement analysis allowed the construction of an idiogram. Bands were divided into “light” (pale on G-banding), “dark” (dark on G-banding) and “grey” (bands not distinguishable).

Whole chromosome probes prepared for chromosome painting

For chromosomal painting studies we used kits produced at the Cambridge Resource Centre for Comparative Genomics, Department of Veterinary Medicine, University of Cambridge, UK, by separation of whole chromosomes using flow cytometry (chromosomes 1–9 of Gallus gallus - GGA - and all chromosomes of Burhinus oedicnemus - BOE). From the products of the primary PCR performed to amplify the DNA of the isolated chromosomes, a second round of DOP-PCR, using 1 µl of product, allowed its labelling with Cy3-dUTP, biotin-16-dUTP (Boehringer Mannheim) or fluorescein isothiocyanate − 12-dUTP (Amersham), subsequently detected with avidin-FITC or avidin-FITC.

For the hybridization experiments, metaphase chromosome preparations were aged for 1 h at 65 °C and treated in 1 % pepsin for 5 min. Chromosomal DNA was denatured at 60 °C in 70 % formamide for 30 seconds. The probes were denatured under the same conditions. The probes were hybridized for three days at 37 °C. After that the slides were washed twice in formamide 50 %, 2xSSC, and once in 4xSSC/Tween at 40˚C. For visualization of the biotin-labelled probes a layer of Cy3-a or Cy5-avidin (1:1000 dilution; Amersham) was used. For FITC-labelled probes we used a layer of rabbit anti-FITC (1:200; DAKO). Slides were mounted in a mounting medium with DAPI called Vectashield (Vector Laboratories) [32].

Generation of Labelled FISH probes for BAC-FISH

Selection of BAC clones

The clones selected for mapping experiments were originally obtained from the BACPAC Resource Centre at the Children’s Hospital Oakland Research Institute and the zebra finch TGMCBa library (Clemson University Genomics Institute). The full set of BAC clones reported in Damas et al. [25] as suitable for inter-species hybridization in birds were used for hybridization. In total, 78 probes from the Gallus gallus and Taeniopygia guttata BAC libraries were tested, of which 40 correspond to GGA and TGA macrochromosomes 1–8 and 38 to GGA and TGA microchromosomes 9–28.

Preparation of BAC clones for FISH

Briefly, BACs were cultured in Luria Bertani Agar (LB Agar) and the clone DNA was extracted by QIAprep Spin Miniprep Kit (Qiagen). BACs were labelled by nick translation using Texas red-12-dUTP (Invitrogen) and FITC-fluorescein-12-UTP (Roche) prior to purification using the Qiagen nucleotide removal kit [25].

Slide preparation for BAC FISH

Chromosome suspensions were dropped on each half of the slide and allowed to air dry. Slides were washed in 2xSSC (Saline-Sodium Citrate) (Gibco) for 2 minutes, dehydrated by serial ethanol washing for 2 minutes each in 70 % (v/v), 85 % and 100 % ethanol and left to air dry.

Fluorescence in situ hybridization for BAC FISH

The probe mix was prepared by adding 1.5 µl of FITC labelled probe, 1.5 µl of Texas Red labelled probe, 1 µl of Gallus gallus Hybloc (Applied Genetics Laboratories), 6 µl of Hyb I (Cytocell) hybridisation buffer to a total volume of 10 µl and a probe concentration of 10 ng/µl. Slides were incubated in a hybridisation chamber at 37 °C for 72 hours and then the slides were washed with 2xSSC with 0.05 % of Tween-20 (Sigma-Aldrich) and stained with Vectashield Antifade Mounting Medium with DAPI (Vectorlab).

Microscopy

Metaphase images were captured using an Olympus BX-61 epifluorescence microscope equipped with a cooled CCD camera and SmartCapture 3 software (Digital Scientific UK). Three different filters were used to acquire images with DAPI, fluorescein isothiocyanate and Texas Red fluorochromes.

Availability of data and materials

All relevant data used in this study are found in the paper.

Abbreviations

- BAC:

-

Chromosomal Artificial of Bacteria

- BOE:

-

Burhinus oedicnemus

- DOP-PCR:

-

Degenerated oligonucleotide-primed polymerase chain reaction

- dUTP:

-

Deoxyuridine triphosphate

- FISH:

-

Fluorescent in Situ Hybridisation

- GGA:

-

Gallus gallus

- TGU:

-

Taeniopygia guttata

- WVI:

-

Willisornis vidua

References

Johansson US, Fjeldså J, Bowie RCK. Phylogenetic relationships within Passerida (Aves: Passeriformes): a review and a new molecular phylogeny based on three nuclear intron markers. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2008;48:858–76.

Barker FK, Cibois A, Schikler P, Feinstein J, Cracraft J. Phylogeny and diversification of the largest avian radiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:11040–5.

Chesser RT. Molecular systematics of New World suboscine birds. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2004;32:11–24.

Irestedt M, Fjeldså J, Nylander JAA, Ericson PGP. Phylogenetic relationships of typical antbirds (Thamnophilidae) and test of incongruence based on Bayes factors. BMC Evol Biol. 2004;4:23. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2148-4-23.

Zimmer KJ, Isler ML. Family Thamnophilidae (Typical Antbirds). In: del Hoyo J, Elliott A, Christie DA, editors. Handbook of the Birds of the World 8. Barcelona: Lynx Edicions; 2003. p. 448–681.

Remsen JVJ, Cadena CD, Jaramillo A, Nores M, Pacheco JF, Pérez-Emán J, Robbins MB, Stiles FG, Stotz DF, Zimmer KJ. A classification of the bird species of South America. American Ornithologists’ Union. Version 30 July 2015. https://doi.org/http://www.museum.lsu.edu/~Remsen/SACCBaseline.html. Accessed 30 Jul 2015.

Piacentini V de. Q. Annotated checklist of the birds of Brazil by the Brazilian Ornithological Records Committee / Lista comentada das aves do Brasil pelo Comitê Brasileiro de Registros Ornitológicos. Rev Bras Ornitol. 2015;23:91–298.

Miranda L, Aleixo A, Whitney BM, Silveira LF, Guilherme E, Santos MPD, Schneider MPC. Molecular systematics and taxonomic revision of the Ihering’s Antwren complex (Myrmotherula iheringi: Thamnophilidae), with description of a new species from southwestern Amazonia. In: del Hoyo J, Elliott A, Christie DA, editors. Handbook of the Birds of the World. Special volume: new species and global index Lynx. Barcelona: Lynx Edicions; 2013. p. 268–71.

Mata H, Fontana CS, Mauricio GN, Bornschein MR, Vasconcelos MF, Bonatto SL. Molecular phylogeny and biogeography of the eastern Tapaculos (Aves: Rhinocryptidae: Scytalopus, Eleoscytalopus): Cryptic diversification in Brazilian Atlantic Forest. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2009;53:450–62.

d’Horta FM, Cuervo AM, Ribas CC, Brumfield RT, Miyaki CY. Phylogeny and comparative phylogeography of Sclerurus (Aves: Furnariidae) reveal constant and cryptic diversification in an old radiation of rain forest understory specialists. J Biogeogr. 2013;40:37–49.

Carneiro LS, Gonzaga LP, Rêgo PS, Sampaio I, Schneider H, Aleixo A. Systematic revision of the Spotted Antpitta (Grallariidae: Hylopezus macularius), with description of a cryptic new species from Brazilian Amazonia. Auk. 2012;129:338–51.

Sousa-Neves T, Aleixo A, Sequeira F. Cryptic patterns of diversification of a widespread Amazonian woodcreeper species complex (Aves: Dendrocolaptidae) inferred from multilocus phylogenetic analysis: implications for historical biogeography and taxonomy. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2013;68:410–24.

Fernandes A, Gonzalez J, Wink M, Aleixo A. Multilocus phylogeography of the Wedge-billed Woodcreeper Glyphorynchus spirurus (Aves, Furnariidae) in lowland Amazonia: widespread cryptic diversity and paraphyly reveal a complex diversification pattern. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2013;66:270–82.

Isler ML, Whitney BM. Species limits in the antbirds (Thamnophilidae): the scale-backed Antbird (Willisornis poecilonotus) complex. Wilson J Ornithol. 2011;123:1–14.

Maldonado-Coelho M, Blake JG, Silveira LF, Batalha-Filho H, Ricklefs RE. Rivers, refuges and the population divergence of fire-eye antbirds (Pyriglena) in the Amazon Basin. J Evol Biol. 2013;26:1090–107.

Aleixo A, Burlamaqui TCT, Schneider MPC, Gonçalves EC. Molecular systematics and plumage evolution in the monotypic obligate army-ant- following genus Skutchia (Thamnophilidae). Condor. 2009;111:382–7.

Whitney Bret, Cohn-Haft MM. Fifteen new species of Amazonian birds In: del Hoyo J, Elliott A, Christie DA, editors. Handbook of the Birds of the World. Special volume: new species and global index Lynx. Barcelona: Lynx Edicions; 2013. p. 225–39.

Kretschmer R, Ferguson-Smith MA, De Oliveira EHC. Karyotype evolution in birds: from conventional staining to chromosome painting. Genes. 2018;9:1–19.

Nagamachi CY, Pieczarka JC, Milhomem SS, O’Brien PC, de Souza AC, Ferguson-Smith MA. Multiple rearrangements in cryptic species of electric knifefish, Gymnotus carapo (Gymnotidae, Gymnotiformes) revealed by chromosome painting. BMC Genet. 2010;11:28.

Silva DS, Peixoto LA, Pieczarka JC, Wosiacki WB, Ready JS, Nagamachi CY. Karyotypic and morphological divergence between two cryptic species of Eigenmannia in the Amazon basin with a new occurrence of XX/XY sex chromosomes (Gymnotiformes: Sternopygidae). Neo Ichthyol. 2015;13:297–308.

da Costa MJR, do Amaral PJS, Pieczarka JC, Sampaio MI, Rossi RV, Mendes-Oliveira AC, et al. Cryptic species in Proechimys goeldii (Rodentia, Echimyidae)? A case of molecular and chromosomal differentiation in allopatric populations. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2016;148:199–210.

Griffin DK, Robertson LBC, Skinner GTH. BM. The evolution of the avian genome as revealed by comparative molecular cytogenetics. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2007;117:64–77.

de Oliveira Furo I, Kretschmer R, O’Brien PC, Ferguson-Smith MA, de Oliveira EHC. Chromosomal diversity and karyotype evolution in South American Macaws (Psittaciformes, Psittacidae). PLoS One. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0130157.

Ellegren H. Evolutionary stasis: the stable chromosomes of birds. Trends Ecol Evol. 2010;25:283–91.

Damas J, O’Connor R, Farré M, Lenis VPE, Martell HJ, Mandawala A, et al. Upgrading short-read animal genome assemblies to chromosome level using comparative genomics and a universal probe set. Genome Res. 2017;27:875–84.

O’Connor RE (a), Farré M, Joseph S, Damas J, Kiazim L, Jennings R et al Chromosome-level assembly reveals extensive rearrangement in saker falcon and budgerigar, but not ostrich, genomes. Genome Biol. 2018;19:1–15.

Nishida C, Ishishita S, Yamada K, Griffin DK, Matsuda Y. Dynamic chromosome reorganization in the osprey (Pandion haliaetus, pandionidae, Falconiformes): relationship between chromosome size and the chromosomal distribution of centromeric repetitive DNA sequences. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2014;142:179–89.

Kretschmer R, Gunski RJ, Garnero ADV, Furo IDO, O’Brien PCM, Ferguson-Smith MA, et al. Molecular cytogenetic characterization of multiple intrachromosomal rearrangements in two representatives of the genus Turdus (turdidae, passeriformes). PLoS One. 2014;9:e103338.

Kretschmer R), Ferguson-Smith MA, de Oliveira EHC. Karyotype evolution in birds: From conventional staining to chromosome painting. Genes (Basel). 2018;9:6–8.

dos Santos M, da S, Kretschmer, Silva R, Ledesma FAO, O’Brien MA, Ferguson-Smith PCM. MA, et al. Intrachromosomal rearrangements in two representatives of the genus Saltator (Thraupidae, Passeriformes) and the occurrence of heteromorphic Z chromosomes. Genetica. 2015;143:535–43.

Griffin DK, Haberman F, Masabanda J, O’Brien P, Bagga M, Sazanov A, et al. Micro- and macrochromosome paints generated by flow cytometry and microdissection: tools for mapping the Gallus gallus genome. Cytogenet Cell Genet. 1999;87:278–81.

Nie W, O’Brien PCM, Ng BL, Fu B, Volobouev V, Carter NP, et al. Avian comparative genomics: Reciprocal chromosome painting between domestic Gallus gallus (Gallus gallus) and the stone curlew (Burhinus oedicnemus, Charadriiformes)-An atypical species with low diploid number. Chromosom Res. 2009;17:99–113.

De Oliveira EHC, Tagliarini MM, Rissino JD, Pieczarka JC, Nagamachi CY, O’Brien PCM, et al. Reciprocal chromosome painting between white hawk (Leucopternis albicollis) and Gallus gallus reveals extensive fusions and fissions during karyotype evolution of Accipitridae (Aves, Falconiformes). Chromosom Res. 2010;18:349–55.

Nie W, O’Brien PCM, Fu B, Wang J, Su W, He K, et al. Multidirectional chromosome painting substantiates the occurrence of extensive genomic reshuffling within Accipitriformes. BMC Evol Biol. 2015;15:205.

Kretschmer R), de Oliveira Furo I, Gunski RJ, del Valle Garnero A, Pereira JC, O’Brien PCM, et al. Comparative chromosome painting in Columbidae (Columbiformes) reinforces divergence in Passerea and Columbea. Chromosom Res. 2018;26:211–23.

Warren WC, Clayton DF, Ellegren H, Arnold AP, Hillier LW, Künstner A, et al. The genome of a songbird. Nature. 2010;464:757–62.

Nanda I, Schlegelmilch K, Haaf T, Schartl M, Schmid M. Synteny conservation of the Z chromosome in 14 avian species (11 families) supports a role for Z dosage in avian sex determination. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2008;122:150–6.

Nishida-Umehara C, Tsuda Y, Ishijima J, Ando J, Fujiwara A, Matsuda Y, et al. The molecular basis of chromosome orthologies and sex chromosomal differentiation in palaeognathous birds. Chromosome Res. 2007;15:721–34.

Kretschmer R, Gunski RJ, Garnero ADV, Furo IDO, O’Brien PCM, Ferguson-Smith MA, et al. Molecular cytogenetic characterization of multiple intrachromosomal rearrangements in two representatives of the genus Turdus (Turdidae, Passeriformes). PLoS One. 2014;9:e103338.

Bülau SE, Kretschmer R, Gunski RJ, Garnero ADV, O’brien PCM, Ferguson-Smith MA, et al. Chromosomal polymorphism and comparative chromosome painting in the rufous-collared sparrow (Zonotrichia capensis). Genet Mol Biol. 2018;41:799–805.

Guttenbach M, Nanda I, Feichtinger W, Masabanda JS, Griffin DK, Schmid M. Comparative chromosome painting of Gallus gallus autosomal paints 1–9 in nine different bird species. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2003;103:173–84.

Derjusheva S, Kurganova A, Habermann F, Gaginskaya E. High chromosome conservation detected by comparative chromosome painting in Gallus gallus, pigeon and passerine birds. Chromosom Res. 2004;12:715–23.

Itoh Y, Arnold AP. Chromosomal polymorphism and comparative painting analysis in the zebra finch. Chromosom Res. 2005;13:47–56.

Nanda I, Benisch P, Fetting D, Haaf T, Schmid M. Synteny conservation of Gallus gallus macrochromosomes 1–10 in different avian lineages revealed by cross-species chromosome painting. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2011;132:165–81.

Kretschmer R, de Oliveira EHC, Dos Santos MS, Furo I, de O, O’Brien PCM, Ferguson-Smith MA, et al. Chromosome mapping of the large Elaenia (Elaenia spectabilis): Evidence for a cytogenetic signature for passeriform birds? Biol J Linn Soc. 2015;115:391–8.

Ribas TFA, Nagamachi CY, Aleixo A, Pinheiro MLS, OBrien PCM, Ferguson-Smith MA, et al. Chromosome painting in Glyphorynchus spirurus (Vieillot, 1819) detects a new fission in Passeriformes. PLoS One. 2018;13:1–13.

Rodrigues BS, Kretschmer R, Gunski RJ, Garnero ADV, O’Brien PCM, Ferguson-Smith M, et al. Chromosome painting in Tyrant Flycatchers confirms a set of inversions shared by Oscines and Suboscines (Aves, Passeriformes). Cytogenet Genome Res. 2018;153:205–12.

Prum RO, Berv JS, Dornburg A, Field DJ, Townsend JP, Lemmon EM, et al. A comprehensive phylogeny of birds (Aves) using targeted next-generation DNA sequencing. Nature. 2015;526:569.

De Lucca EJ, Rocha GT. Citogenética de Aves Bol. Mus Para Emilio Goeldi Série Zool. 1992;8:33–68.

Santos LP, Gunski RJ. Revisão de dados citogenéticos sobre a avifauna brasileira. Rev Brasil Ornitol. 2006;14:35–45.

Ledesma MA, Garnero ADV, Gunski RJ. Análise do cariótipo de duas espécies da família Formicariidae (Aves, Passeriformes). Ararajuba. 2002;10:15–9.

Lucca EJ. Cariótipo de 14 espécies de Aves das Ordens Cuculiformes, Galliformes, Passeriformes e Tina- miformes. Rev Bras Pesq Med Biol. 1974;7:253–63.

Lucca EJ, Chamma L. Estudo do complemento cromossômico de 11 espécies de aves das Ordens Columbiformes, Passeriformes e Tinamiformes. Rev Bras Pesq Med Biol. 1977;10:97–105.

de Oliveira EHC, Habermann FA, Lacerda O, Sbalqueiro IJ, Wienberg J, Müller S. Chromosome reshuffling in birds of prey: the karyotype of the world’s largest eagle (Harpy eagle, Harpia harpyja) compared to that of the Gallus gallus (Gallus gallus). Chromosoma. 2005;114:338–43.

De Oliveira EHC, De Moura SP, Dos Anjos LJS, Nagamachi CY, Pieczarka JC, O’Brien PCM, et al. Comparative chromosome painting between Gallus gallus and spectacled owl (Pulsatrix perspicillata): implications for chromosomal evolution in the Strigidae (Aves, Strigiformes). Cytogenet Genome Res. 2008;122:157–62.

Nanda I, Karl E, Volobouev V, Griffin DK, Schartl M, Schmid M. Extensive gross genomic rearrangements between Gallus gallus and Old World vultures (Falconiformes: Accipitridae). Cytogenet Genome Res. 2006;112:286–95.

Hansmann T, Nanda I, Volobouev V, Yang F, Schartl M, Haaf T, et al. Cross-species chromosome painting corroborates microchromosome fusion during karyotype evolution of birds. Cytogenet Genome Res. 2010;126:281–304.

Jarvis ED, Ye C, Liang S, Yan Z, Zepeda ML, Campos PF, et al. A phylogeny of modern birds. Science. 2014;346:1126–38.

Cracraft J, Prum RO. Patterns and processes of diversification: speciation and historical congruence in some neotropical birds. Evolution. 1988;42:603.

Ayres JM, Clutton-Brock TH. River boundaries and species range size in Amazonian primates. Am Nat. 1992;140:531–7.

Bates JM, Hackett JSCJ. Area-relationships in the neotropical lowlands: a hypothesis based on raw distributions of passerine birds. J Biogeogr 1998;25:783–93.

Silva JM, Novaes FC, Oren DC. Differentiation of Xiphocolaptes (Dendrocolaptidae) across the river Xingu, Brazilian Amazonia: recognition of a new phylogenetic species and biogeographical implications. Bull B O C. 2002;122:185–94.

Silva SM, Peterson AT, Carneiro L, Burlamaqui TCT, Ribas CC, Sousa-Neves T, et al. A dynamic continental moisture gradient drove Amazonian bird diversification. Sci Adv. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aat5752.

Weir JT, Faccio MS, Pulido-Santacruz P, Barrera-Guzmán AO, Aleixo A. Hybridization in headwater regions, and the role of rivers as drivers of speciation in Amazonian birds. Evolution. 2015;69:1823–34.

Thom G, Aleixo A. Cryptic speciation in the white-shouldered antshrike (Thamnophilus aethiops, Aves - Thamnophilidae): The tale of a transcontinental radiation across rivers in lowland Amazonia and the northeastern Atlantic Forest. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2015;82:95–110.

Pulido-Santacruz P, Aleixo A, Weir JT. Morphologically cryptic Amazonian bird species pairs exhibit strong postzygotic reproductive isolation. Proc Biol Sci. 2018. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2017.2081.

O’Connor RE, Kiazim L, Skinner B, Fonseka G, Joseph S, Jennings R, et al. Patterns of microchromosome organization remain highly conserved throughout avian evolution. Chromosoma. 2019;128:21–9.

Skinner BM, Griffin DK. Intrachromosomal rearrangements in avian genome evolution: evidence for regions prone to breakpoints. Heredity. 2012;108:37–41.

O’Connor RE (c), Romanov MN, Kiazim LG, Barrett PM, Farré M, Damas J et al Reconstruction of the diapsid ancestral genome permits chromosome evolution tracing in avian and non-avian dinosaurs. Nat Commun. 2018;9:1–9.

Kretschmer R, de Lima VLC, de Souza MS, Costa AL, O’Brien PCM, Ferguson-Smith MA, et al. Multidirectional chromosome painting in Synallaxis frontalis (Passeriformes, Furnariidae) reveals high chromosomal reorganization, involving fissions and inversions. Comp Cytogenet. 2018;12:97–110.

Selvatti AP, Gonzaga LP, Russo CAM de. A Paleogene origin for crown passerines and the diversification of the Oscines in the New World. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2015;88:1–15.

O’Connor RE (a), Farré M, Joseph S, Damas J, Kiazim L, Jennings R et al Chromosome-level assembly reveals extensive rearrangement in saker falcon and budgerigar, but not ostrich, genomes. Genome Biol. 2018;19:1–15.

Garnero AV, Gunski RJ. Comparative analysis of the karyotype of Nothura maculosa and Rynchotus rufescens (Aves: Tinamidae). A case of chromosomal polymorphism. Nucleus. 2000;43:64–70.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to Museu Paraense Emilio Goeldi for logistic support to collect samples in Juruti, Belém and Flona Tapajós; we also thank to Dr. Luis Rodrigues from Universidade Federal do Oeste do Pará – UFOPA, for logistic support to collect samples in Flona Tapajós; to Bruno de Almeid, Marlyson Jeremias, Luyan Rodrigues and Leony Dias for help us in the field work; to Profa. Dr Maria Luisa for logistic support to collect samples in Santa Bárbara in Parque Ecológico do Gumna. We also thank the anonymous reviewers for their suggestions; to University of Kent for the laboratory support during TFAR Doctoral Sandwich period under CAPES Scholarship.

Funding

This study was part of Doctoral thesis of Dr TFAR in Genetics and Molecular Biology, under a CAPES Doctoral Scholarship included in a project Pró-Amazônia (Proc. 047/2012) coordinated by CYN. CYN (305880/2017-9) and JCP (305876/2017-1) are grateful to CNPq for Productivity Grants. Funding: Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq), the Fundação Amazônia Paraense de Amparo à Pesquisa (FAPESPA); the FAPESPA (Edital Vale – Proc 2010/110447) and Banco Nacional de Desenvolvimento Econômico e Social – BNDES (Operação 2.318.697.0001) on a project coordinated by J.C. Pieczarka; Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (GB) (BB/K008161/1). The funding bodies did not have any role in the design of the study, collection, analysis and interpretation of data, or in writing the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

TFAR, JCP, CYN, AA, DKG, ROC and LGK designed the study and planned the experiments. TFAR sampled the individuals. TFAR, JCP, LGK, DKG, ROC performed the experiments and analysed the chromosomal data; and AA analysed morphological data for species distinction. DKG, ROC and LGK performed the confection of the BAC Probes. PCOB, FY and MFS performed the confection and sorting of the probes of GGA and BOE. TFAR wrote the first draft. All the authors contributed to the final version. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

The Ethics Committee (Comitê de Ética Animal da Universidade Federal do Pará) approved this research (Permit 68/2015).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Addtional file 1

. Phylogenetic relationship among chicken, zebra finch, the Eurasian Stone Curlew and the Wedge-Billed Woodcreeper. The phylogeny is based in Prum et al. [48].

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Ribas, T.F.A., Pieczarka, J.C., Griffin, D.K. et al. Analysis of multiple chromosomal rearrangements in the genome of Willisornis vidua using BAC-FISH and chromosome painting on a supposed conserved karyotype. BMC Ecol Evo 21, 34 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12862-021-01768-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12862-021-01768-y