Abstract

Background

The coincidence of long distance dispersal (LDD) and biome shift is assumed to be the result of a multifaceted interplay between geographical distance and ecological suitability of source and sink areas. Here, we test the influence of these factors on the dispersal history of the flowering plant genus Erica (Ericaceae) across the Afrotemperate. We quantify similarity of Erica climate niches per biogeographic area using direct observations of species, and test various colonisation scenarios while estimating ancestral areas for the Erica clade using parametric biogeographic model testing.

Results

We infer that the overall dispersal history of Erica across the Afrotemperate is the result of infrequent colonisation limited by geographic proximity and niche similarity. However, the Drakensberg Mountains represent a colonisation sink, rather than acting as a “stepping stone” between more distant and ecologically dissimilar Cape and Tropical African regions. Strikingly, the most dramatic examples of species radiations in Erica were the result of single unique dispersals over longer distances between ecologically dissimilar areas, contradicting the rule of phylogenetic biome conservatism.

Conclusions

These results highlight the roles of geographical and ecological distance in limiting LDD, but also the importance of rare biome shifts, in which a unique dispersal event fuels evolutionary radiation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The current day distributions of many plant groups are the result of long distance dispersal (LDD) [1,2,3,4,5]. Such events are thought to be rare ([6] but see [7]), but rarer still might be plant dispersals across long distances between different biomes [8]. The coincidence of intercontinental dispersal and biome shift, such as inferred in Lupinus [9], Bartsia [10], and Hypericum [11], is assumed to be the result of a multifaceted interplay between geographical distance and ecological suitability of source and sink areas [12]. Here, we test the influence of these factors on the biogeographic history of the flowering plant genus Erica (Ericaceae).

The more than 800 Erica species across Europe and Africa provide an excellent example with which to test the impact of geographical and ecological distance on biogeographic history. Just 21 of the species are found in Central and Western Europe, Macaronesia, the Mediterranean and the Middle East. This species-poor assemblage nevertheless most likely represents the ancestral area of the clade [13,14,15] where the oldest lineages began to diversify c. 30 Ma [16]. From around 15 Ma, a single lineage dispersed across different biomes of the Afrotemperate (sensu White [17]): today 23 species are known from the high mountains of Tropical Africa; 51 in Southern Africa’s Drakensberg Mountains; c. 41 in Madagascar and the Mascarene islands; and c. 690 in the Cape Floristic Region of South Africa [16, 18]. Present day habitats of Erica species tend to be low nutrient and fire prone [19], but still differ markedly in ecology, from the Mediterranean climates of southern Europe and the Cape to colder climes of northern Europe and the non-seasonal temperate habitats of the high mountains in Tropical Africa. These habitats are also separated by considerable geographic distances, isolated by expanses of inhospitable ecosystems and/or ocean. Nonetheless, similar distribution patterns across Europe and Africa are observed in different plant groups (e.g. [20, 21]).

Organisms adapted to different habitats respond differently to changing environmental conditions [22, 23]. For example, plant groups with greater tolerances of aridity than Erica may have had more contiguous past distributions across Africa [24]. Similar distribution patterns of such groups might thus be best described by biogeographic scenarios emphasising vicariance processes, such as for example the “Rand Flora”, representing plant lineages that show similar disjunct distributions around the continental margins of Africa [25, 26], or the “African arid corridor” hypothesis that seeks to explain disjunct distributions between the Horn of Africa and arid south-western Africa [27, 28]. By contrast, similar distribution patterns observed across plants such as Erica that are adapted, or otherwise restricted, to habitats that remained largely isolated over time might instead be explained by concerted patterns of LDD [29,30,31,32]. Examples include the shared arid adapted elements of Macronesia and adjacent North-West Africa and Mediterranean [33,34,35], and the more mesic temperate or tropical alpine habitats of the “sky islands” of East Africa, in which, for example, multiple lineages originated from northern temperate environments [21, 36, 37].

A more specific biogeographic scenario, inferred from Cape clades with distributions very similar to that of Erica, involves dispersal north from the Cape to the East African mountains via the Drakensberg (“Cape to Cairo” [20];). McGuire & Kron [14] proposed a different scenario for Erica instead: southerly stepping stone dispersal through the African high mountains to the Cape. Both scenarios, however, imply that dispersal is more frequent between adjacent areas/over shorter distances. Short distance or stepping stone dispersal may indeed be more probable than LDD [6], and distance alone could conceivably be more important than directionality [38]. On the other hand, the probabilities of LDDs are hard to model [6, 39], in part because (observable) LDD events also involve successful establishment in more or less distinct environments [12]. Thus geographic distance and ecological suitability might individually constrain the biogeographic history of plants, or the interplay between both factors may be decisive [40, 41], so much so that clades with similar ecological tolerances and origin might show convergence to similar distribution patterns [21, 23, 42].

In this paper, we ask whether and to what extent geographic proximity or climatic niche similarity constrained the colonisation of the Afrotemperate by Erica. Until recent work [16, 43], too little was known of the phylogenetic relationships of the 97% of Erica species outside Europe to be able to address such questions. Specifically, we test six biogeographic models, as illustrated in Fig. 1: Three that test the influence of geographic distance, climatic niche similarity, and the combination of both; and three area adjacency-based stepping stone models: northerly “Cape to Cairo”, “Southerly stepping stone” and a model that invokes elements of both, the “Drakenberg melting pot” hypothesis.

Biogeographic hypotheses. The pure geographic distance model; niche similarity, implying colonisation of areas with the most similar climatic niche (Donoghue 2008); these together constituting a combined geographic and niche similarity model; stepping stone: stepwise southerly colonisation of the Afrotemperate from Europe (following McGuire and Kron, 2005); Cape to Cairo: stepwise northerly colonisation of the Afrotemperate from the Cape (following Galley et al., 2007); necessarily preceded by LDD from Europe; and Drakensberg melting pot: the Drakensberg colonised by both southerly and northerly stepwise dispersal

Materials and methods

Phylogenetic hypothesis: Analyses were based on phylogenetic trees ([16]; TreeBase study accession URL: http://purl.org/phylo/treebase/phylows/study/TB2:S18291) which represent c. 60% of the c. 800 species of Erica from across their geographic range and DNA sequences from multiple plastid markers (trnT-trnL and trnL-trnF-ndhJ spacer sequences for all taxa, with exemplar sampling of trnL intron, atpI-atpH spacer, trnK-matK intron and matK gene, psbM-trnH spacer, rbcL gene, rpl16 intron, trnL-rpl32 spacer sequences) and nuclear ribosomal (nrDNA) internal transcribed spacer (ITS; for all taxa). For the biogeographic analyses here, we adopt the phylogenetic hypothesis of Pirie et al. (2016), the best tree inferred under Maximum Likelihood (ML) using RAxML [44], based on the combined data and 597 taxa and rate smoothed using RELTIME [45] with a single secondary calibration point derived from a wider fossil calibrated analysis of Ericaceae [46]. Pirie & al [16]. identified a “Cape clade” that included all but one of the sampled species of Erica found in the CFR. The single exception was E. pauciovulata, which was placed within a polytomy including the Cape clade and other Afrotemperate lineages. This may, however, be artefactual due to sequence anomalies in the trnL-trnF-ndhJ spacer region of E. pauciovulata. Preliminary results based on additional sampling including nrDNA ETS (Pirie et al. in prep.) confirm the monophyly of Cape clade including E. pauciovulata, and we therefore exclude this taxon from biogeographic analyses to avoid inferring an independent colonisation of the CFR as a result of its uncertain position.

Defining the pure-distance and the niche-based models: Five biogeographic areas of the Erica distribution were defined following Pirie et al. [16]: Europe (including northern Africa); Tropical Africa (TA); Madagascar; Drakensberg; Cape. For each of these areas we estimated the joint range of all the documented Erica species by summing the union of the species point distributions (which we term ‘area ranges’; see below). To do this, we obtained occurrence data for Erica species from our own collections, and from PRECIS (representing mostly southern African collections, held by the South African National Biodiversity Institute; http://newposa.sanbi.org/) and GBIF (https://www.gbif.org/) databases. We curated the species occurrence data by removing obviously erroneous locality data, duplicated records, and records with less precise occurrence data (coordinates with ≤3 decimal places, a cut-off which also served to exclude the centroids of quarter degree squares which were originally represented in PRECIS and which for this purpose unhelpfully summarise multiple records to single inaccurate points). We did not further consider the source of or information on the precision of the geographical coordinates, because these are most often not stated in the database-derived occurrence records. This resulted in 6818 individual occurrences representing the species in the phylogenetic trees (Additional file 1). The distribution of these occurrences was skewed in favour of larger and better collected areas (Europe 4667, Tropical Africa 42, Madagascar 70, Drakensberg 58, and Cape 1981; Additional file 2). We aimed at a representative approximation of spatial extent [47, 48] and ecological conditions of species distributions per biogeographic area, whilst reducing this skew. To this end, we coarsened the individual occurrence data, placing a buffer of one minutes of arc in radius (ca. 11 km) and 50 m elevation around the individual species occurrences. This resulted in area ranges including up to several thousands of spatial points, with a reduction of the discrepancy in numbers of points per area compared to the original data (e.g. 1233 for Europe and 311 for Tropical Africa). These were used in the subsequent analyses to calculate geographical and ecological distances between biogeographic areas.

To incorporate a measure of geographic proximity among areas in a solely distance-based biogeographic model (the ‘geographic distance’ model; Fig. 1), we calculated the overall minimum geographic pairwise distances between the area ranges according to Meeus [49] in WGS84 projection using the raster 2.3–33 package [50] in R [51]. We converted geographic distances into dispersal rate multipliers (0–1, whereby the largest distance has the smallest dispersal probability), while comparing the effect of scaling the distances linearly (applying a linear model with intercept of 1 and a slope of − 1.52− 07 based on distances in meters as predictors) and exponentially (− 0.25, − 1 and − 2).

To incorporate in a niche-based biogeographic model, the ‘niche similarity’ model (Fig. 1), a measure of climatic similarity between the biogeographic areas we built a multidimensional environmental model representing the full space of all available climates in the global study area (i.e. most of Europe and entire Africa, represented by > 0.5 million spatially independently sampled point locations; Additional file 2) using principal component analysis (PCA) in R’s ade4 1.6–2 [52]. To obtain a pairwise climate similarity between the biogeographic areas (i.e., between the area ranges defined by the species occurrence data; see above) we used the niche similarity metric D of Schoener ([53]; Schoener’s D, ranging from 0 = no similarity, to 1 = identical). Because we were comparing the climates in different regions, we corrected the similarity metric D by the ratio of the kernel density distribution of the available climates (bioclim variables) and the biogeographic areas (spatial points of area ranges) in our gridded environmental space using ecospat 2.1.1 [54]. This framework corrects for differences in the available climates between different regions, and is appropriate to compare environmental similarity between any kinds of entities that differ geographically [55]. We further corrected for skew in the numbers of spatial points per area using 1000 iterations subsampling 1000 spatial points per area (i.e. with replacement for the areas with < 1000 spatial points). We used these pairwise Schoener‘s D values (mean of PCA axes 1 and 2) as dispersal rate multipliers between areas in the biogeographic niche similarity model (for details see protocol in Additional file 2).

Finally, to consider both geographical and environmental distances in a joint model, also accounting for a negative correlation between both geographic and environmental distances (Kendall’s R = − 0.64), we used two rate multiplier matrices, representing both climatic niche and physical distance (converted into probabilities; see above), as input.

Biogeographic model testing and ancestral area reconstruction: We used BioGeoBEARS [56] for parametric model testing, whilst aware of the debate surrounding these models and their comparison ([57]; see Results and Discussion). The above defined biogeographic models (Fig. 1) were parameterized using different dispersal rate multipliers (see below and Additional file 3) and compared to null models that do not incorporate any constraints. As input data we used the rate-smoothed ML phylogeny reduced to one tip per sampled species ([16]; the “best tree”), a file delimiting the distributional range of species, and a file indicating connectivity/distance between the different areas of the Erica distribution (varying for the different biogeographic models; Fig. 1, Additional file 3). Model fit of the different nested and non-nested models was tested using the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) and the delta AIC [58]. For model testing we additionally used nine trees from the RAxML bootstrap analyses of Pirie et al. [16] of the same dataset (rate-smoothed using the ape package in R [59];). These trees were selected to represent the possible resolutions of phylogenetic uncertainty between the geographically restricted major clades (Additional file 4) but were otherwise chosen randomly with respect to topologies and branch lengths. All hypotheses were implemented with combinations of dispersal-extinction-cladogenesis (DEC [60, 61];), Bayarea-like or DIVA-like models, with or without allowing long distance dispersal (the “+J” model; [62]). We focus on DEC and DEC + J models because these generally fit the data better than Bayarea-like or DIVA-like models.

Prior to comparing the different biogeographic hypotheses, we tested the influence of several assumptions on our biogeographic estimations. Firstly, we tested whether an unconstrained model fitted the data better than (a) restricting the maximum number of areas at nodes to two; and/or (b) implementing an adjacent area matrix (Additional file 3; Results). The Southerly stepping stone, Cape to Cairo, and Drakensberg melting pot hypotheses were then run, additionally under a range of different dispersal multipliers (0.00, 0.01, 0.05, 0.075, 0.1, 0.25 and 0.5; and for the DEC + J model also on the nine bootstrap trees with dispersal multipliers of 0.01, 0.1, 0.25 and 0.5) to test whether these arbitrary values influenced the results. Secondly, in the niche- and distance-based biogeographic models differently scaled (see above) geographic distances were parameterized as dispersal rate multipliers (Additional file 3). Finally, we assessed the impact on model fit of a number of different values for the parameter “w” (given the best fitting model), which is an exponent for the dispersal multipliers (which otherwise was fixed to “1”; Additional file 3); and coding of E. arborea as European (following [13]), rather than as widespread between Europe and Tropical Africa. After considering phylogenetic uncertainty and the different assumption described, altogether we estimated model fit of almost 250 differently parameterized biogeographic models. In addition, to test for the potential impact of sampling bias given differing proportions of species sampled for the different areas, we modified the best tree 10 times, randomly removing tips corresponding to particular areas to reduce all area sampling to that of Madagascar (42%), and recalculated the models. Further details and example files for the BioGeoBEARS analyses are presented in Additional file 3.

Estimating dispersal rates: For the best models under both DEC + J and DEC, given the best tree, we estimated the number and type of biogeographic events across the clade using Biogeographical Stochastic Modelling (BSM) as implemented in BioGeoBEARS [62]. BSM simulates histories of the times and locations of dispersal events. Frequencies were estimated by taking the mean and standard deviation of event counts from 50 BSMs. We also compared the results to that of simple parsimony optimisation using Mesquite v3.31 [63], under the assumption that LDD events are simply rare [64]. We incorporated phylogenetic uncertainty by summarising the results over the complete sample of 252 RAxML bootstrap trees adapted from Pirie & al [16]., and coding E. arborea either as widespread between Europe and Tropical Africa or European (Additional file 5).

Results

Niche similarity model: The environmental space that represents all climates available in the study area – most of Europe and all of Africa – and that was used to approximate the climatic similarity between biogeographic areas (area ranges), explained > 88% of the climate variation on the first two PCA axes. Despite the range of environmental conditions within the biogeographic areas, e.g. with rainfall seasonality differing according to elevation, the variation in overall climatic similarity between the areas was considerable (the distribution and the median values for Schoener’s D per PCA axis pairwise for the areas are presented in Additional file 6, and for the combined axes 1 and 2 in Additional file 7). According to this, the Cape and Drakensberg areas are climatically most similar (D: 0.71) and Europe and Madagascar are most different (D: 0.21). More similar to the European are the Cape and Drakensberg climates (both D: 0.35), and the Tropical Africa climate (D: 0.27; Fig. 2 c).

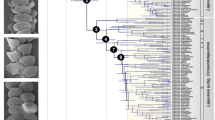

Biogeographic scenario. a) Inferred dispersal scenario between the biogeographic areas (colour coded “area ranges” as assessed by the buffered species occurrence data) depicted on the global study area. b) The phylogeny of Erica with a representation of ancestral areas derived from a single BSM analysis using the best tree and model (under DEC + J). c) Climate similarity between area ranges given as hypervolume corrected pairwise climate similarity (Schoener’s D; with D ≥ 0.5 in dark grey, and D < 0.5 in light grey; Table S8) with superimposed black arrows scaled to the dispersal rates per Ma inferred between areas (Table S13). Ma, million years

Biogeographic model testing: Assuming that AIC values of the differing models can be compared (but see Ree and Sanmartín, 2018), DEC/DEC + J models generally fit the data better than Bayarea-like or DIVA-like models and DEC + J models generally fit the data better than equivalent DEC ones (Additional file 8). Under DEC + J, models including an adjacent area matrix fitted the data better than those without constraint to dispersal. We additionally fixed the maximum number of ancestral areas to two, increasing the speed of the analyses without negatively impacting model fit. Under DEC, models with maximum areas at nodes restricted to two fitted the data better than those without constraint to ancestral ranges. Under both DEC + J and DEC, geographic distance fitted the data better when translated linearly into dispersal rate probabilities (0–1) than when scaled exponentially (Additional file 8); we therefore focus on models using the probabilities, referring to them simply as “geographical distance”. The DEC + J results in general do not show the flaws as reported by Ree and Sanmartín [57]. For example, the values for range expansion (parameter d) were similar and low (0.0030 and 0.0027 per Ma respectively; Additional file 9). Under DEC + J, cladogenetic dispersal (parameter j) was 0.0024 per node, i.e. lower than d (particularly given an average branch length across the Erica phylogeny of 1.78 Ma, variance of 11.67) and much lower than the maximum permitted value (3).

Under DEC + J given the best tree, the “Drakensberg melting pot”, “geographic distance”, and “Southerly stepping stone” models revealed the best fit (lowest AIC with deltaAIC ≥2); under DEC the Drakensberg melting pot model alone scored best, but with AIC 141 compared to AIC 131 for DEC + J (Additional file 8). Adopting DEC + J as the generally better fitting and biologically more realistic model (see Discussion), we assessed the results given phylogenetic uncertainty represented by selected bootstrap trees. Based on the bootstrap trees, the combined niche-geographic distance hypothesis was often among the best fitting models (deltaAIC < 2 given eight of nine trees), scoring better than pure distance (deltaAIC < 2 for five trees), or niche similarity (deltaAIC < 2 for four trees) alone. The “Cape to Cairo” model generally fitted better than most other biogeographic scenarios (deltaAIC < 2 for eight of nine trees, compared to Drakensberg melting pot (deltaAIC < 2 for two of nine trees) and southerly stepping stone (not amongst the best fitting models); Table 1; Additional file 8).

Ancestral area reconstruction: Overall, we infer a colonisation path of Erica from Europe to the Cape via an initial migration to Tropical Africa, under DEC + J and irrespective of best fitting model or phylogenetic uncertainty. When E. arborea is treated as widespread between Europe and Tropical Africa, the common ancestor of the African/Madagascan clade is inferred to have been similarly widespread. When E. arborea is treated as ancestrally European, dispersal from Europe to Tropical Africa is inferred without a transitional widespread distribution. Under DEC, the colonisation path to the Cape is also via an initial migration to Tropical Africa, then a widespread distribution between Tropical Africa and the Cape, followed by an extinction in Tropical Africa. Whether E. arborea is treated as widespread between Europe and Tropical Africa or not, the common ancestor of the African/Madagascan clade is inferred to have been similarly widespread between Europe and tropical Africa. Reducing overall species sampling to 42% did not change the overall pattern of model fit (Additional file 8d). Ancestral area reconstructions given the best tree under the best fitting models (as well as under a model without range or dispersal constraints for comparison; in each case under both DEC + J and DEC) are presented in Additional file 13. Overall, ancestral areas inferred under parsimony were consistent with those inferred under parametric models (more so with those under DEC + J, given that widespread distributions are not incorporated into standard character optimisation), with the numbers and directions of shifts unaffected by phylogenetic uncertainty.

The vast majority of biogeographic events inferred using BSM under both DEC + J and DEC were within-area speciation (97.15 and 96.26% respectively; Additional file 9). Under DEC + J, few range expansion events were inferred between Europe and Tropical Africa and between Tropical Africa and the Drakensberg region, with most between Cape and the Drakensberg regions (Additional file 10). Dispersal rates between area ranges inferred under BSM are summarised in Fig. 2 c. A single founder event (parameter j) was inferred from Tropical Africa to the Cape region, with fewer events between the Drakensberg and Tropical Africa and between Tropical Africa and Madagascar. Overall, most founder events took place from Tropical Africa (1.96 [standard deviation of 0.47] events averaged across 50 BSM; Additional file 11). In addition to the most commonly inferred range expansions given DEC + J, under DEC additional range expansions were inferred from Tropical Africa to Madagascar and from Tropical Africa to the Cape (Additional file 10). With each range expansion under DEC, the corresponding ancestral distribution was widespread. Under both DEC + J and DEC dispersal rates between Tropical Africa and the Drakensberg were roughly symmetrical, as opposed to those between the Cape and the Drakensberg or between Europe and Tropical Africa which were asymmetrical (Fig. 2; Additional file 12).

Discussion

In this study, we modelled shifts between biomes and dispersals over larger distances in the evolution of Erica, in order to test six hypotheses for the origins of Afrotemperate plant groups (Fig. 1). Three models concerned general factors considered of importance in limiting plant dispersal: geographical distance, similarity of realised climatic niches, and a combination of geographical and ecological proximity. The remaining three models described specific colonisation hypotheses of the Afrotemperate, in each case proposing a stepwise shift in distributions between adjacent areas. These models differed in the area of origin and in the direction of dispersal: northerly dispersal from the Cape (“Cape to Cairo”), versus southerly dispersal from Europe (“Southerly stepping stone”), or a combination of both (termed here “Drakensberg melting-pot”).

Of the stepping-stone-dispersal models, “Cape to Cairo” and/or “Drakensberg melting-pot” fit the data better than “Southerly stepping stone” for all but the best tree, but relative fit of the models was somewhat sensitive to phylogenetic uncertainty (Table 1). By contrast, the positions of areas relative to one another, and the similarities in their realised climatic niche, were consistently prominent in our results. Of the distance models, the combination of geographical and ecological distance fit the data well. Our results showed that these factors are correlated across the Erica distribution, but nevertheless given the phylogenetic uncertainty it was the combination of both that often fitted the data better than either factor individually (or indeed the stepping stone models). The generally better fit of the combined geographic and realised niche model affirms the concerted importance of both factors in shaping distributional patterns of plants [12, 40]. Of the nine range expansion events that we inferred (DEC + J, best tree, best model), seven respectively were between adjacent areas or between areas with similar environmental conditions (where “similar” is arbitrarily defined as a pairwise Schoener’s D > 0.5; Fig. 2). Overall, this represents striking evidence for geographical and ecological distance constraining past and present distributions of Erica species, similar to that inferred for other Mediterranean climate plant groups [65]. Irrespective of model fit, the sequence of dispersal events that we inferred from ancestral area reconstructions, based on both the set of best fitting parametric models and a parsimonious interpretation of the infrequent dispersal events (Fig. 2), does resemble a “Drakensberg melting-pot” scenario. The Drakensberg acted as a sink for dispersals from the adjacent Cape and Tropical African regions, but not as a stepping stone (or indeed a “springboard” [20]).

Cape lineages found in the Drakensberg have not dispersed to Tropical Africa, and neither have Tropical Africa lineages found in the Drakensberg dispersed further to the Cape. This is unexpected, not only because of the low distances and high niche similarities involved, but also because of the equivalent events inferred in other similarly distributed plant groups [20]. Striking in a different way are three unique events: the single dispersals from Europe to Tropical Africa, out of Tropical Africa to the Cape, and out of Tropical Africa to Madagascar, which were each over much longer distances. The dispersals to Tropical Africa and to Madagascar both might have involved shifts in realised niches (indicated by low Schoener‘s D values of 0.298 and 0.274 respectively); that to the Cape, borderline so (Schoener‘s D of 0.560; Fig. 2). Notably, the dispersals to tropical Africa and to the Cape coincided with clear increases in diversification rate [16].

Potential explanations for these apparent exceptions to the general importance of geographical and ecological distance might be found in the context of the changing climates and geology of the African continent during the timeframe of the Erica radiation. The summer-arid climate of the present day Cape has been linked to the establishment of the cold Benguela current off the south-west African coast in the mid Miocene 14–10 Ma [66, 67]. Evidence from pollen deposited in nearby marine sediments shows an accumulation of typical Cape lineages since roughly the same time, including Ericaceae [68], supported by further evidence from recent dated phylogenies both for the ages of clades in the Cape (e.g. [69, 70]) and the origins of fire adapted lineages [71]. The gradual change from a more tropical to a mesic flora and initiation of a regular fire regime in south-western Africa might be ecological changes important for the establishment of Erica in the Cape. Whilst the mountains of the Western Cape, home to much of the Erica-dominated fynbos vegetation, long predate Miocene climatic changes, the origins of the Drakensberg and Tropical African high mountains, Erica’s area of first establishments in Africa, are more recent, with uplift in these regions creating montane habitats from the Miocene onwards [72].

Thus, shifting climates and mountain building created an archipelago of temperate islands across sub-Saharan Africa that were available for colonisation by plants able to tolerate the novel conditions. These included Erica species, which had begun to diversify c. 30 Ma in the Northern Hemisphere [16], and which as a clade are characterised by drought resistant leaves [73] as well as adaptations to post-fire regeneration [19]. However, our analyses of the realised climatic niches of Erica species in their different biomes suggests that despite these pre-existing drought and fire adaptations, colonisation of new areas by Erica involved further adaptation (sooner or later) to rather different climatic conditions, as inferred for tropical alpine Hypericum in South America [11] and hypothesised for tropical high alpine plants in general [74]. In this context, biome shifts and increased diversification rates may be linked: the open field presented by these newly formed, isolated, temperate habitats may have facilitated both the chance establishment of suboptimally adapted plants and their subsequent in situ shift into new adaptive zones, promoting accelerated diversification.

Neither differences in ecological nor geographic distance present an obvious explanation for why dispersal to the Drakensberg was not followed by further independent colonisations, particularly of the Cape. One possibility could be that within the Drakensberg, Cape and Tropical African elements occupy somewhat differing niches: the former, such as the widespread Cape-Drakensberg species E. cerinthoides and E. caffra predominantly at lower elevations, the latter at higher elevations under conditions differing more to those in the Cape. Another could be niche pre-emption [75], whereby the single colonisation and rapid species radiation of Cape Erica prevented further colonisation by similar competitors.

Widespread species such as E. cerinthoides and E. caffra, found in the Cape and Drakensberg, and E. arborea, found in Europe and Tropical Africa [37, 76], are exceptional in Erica. Almost all extant species are restricted to just one of the areas as defined here and the species radiations leading to most of the present day diversity of Erica were within single areas [16]. Improved sampling particularly of Tropical African species (those least well represented in these analyses) would be useful to test this result, as well as to infer the origins of species such as E. silvatica and E. benguelensis that are widespread across disjunct areas within Tropical Africa. Nevertheless, the current results suggest that most species ranges were restricted throughout the evolution of the Erica African/Madagascan clade, that the broader biogeographic areas remained mostly isolated during this period (i.e. the last c. 15 Ma [16];), and hence that still un-sampled species are likely to be members of already known geographically restricted clades. We would also argue that it lends credibility to results obtained under DEC + J, in which some range shifts were treated as cladogenetic dispersal events (instead of by inferring seemingly implausible widespread distributions), despite arguable drawbacks in the implementation of that model [57, 77]. However, the extent and position of suitable habitats across the Afrotemperate shifted considerably during this timeframe, and the implicit assumption of our analyses, that they can be treated as consistent during the Erica diversification, is a considerable simplification. This may not impact the overall results of a broader scale analysis such as the one we present here, but could influence interpretation of the results if, for example, when Erica dispersed from Tropical Africa to the Cape, conditions in these areas were more similar (or different) than they are today. Changing climatic conditions through time are likely to be particularly important in the context of diversifications within regions, such as those within the Cape [68, 70, 78, 79] or Drakensberg [80]. To assess the impact of climatic changes on the dramatic radiation of Cape Erica, for example, it would be important to translate realised niches into past distributions to model the shifting extents and interconnectedness of populations through time (cf. [23]).

Conclusions

The overall picture to be gleaned from the colonisation history of Erica across the Afrotemperate is one of infrequent dispersal limited by geographic distance and ecological similarity. Lack of dispersals where they might be expected – in the case of Erica, the Drakensberg acting as a sink, rather than stepping stone to wider dispersal – can point to biological and historical idiosyncrasies of particular lineages. Our results also show the importance of single unique events that can run counter to general trends. In Erica, three particularly long distance dispersals, two potentially with shifts in the realised niche, were followed by species radiations – most notably in the Cape – that dominate the narrative of the group as a whole. Our results serve to further emphasise the importance of such rare events, in which unique biome shifts fuel dramatic evolutionary radiations.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are available in the TreeBase repository (http://purl.org/phylo/treebase/phylows/study/TB2:S18291) or included within the article (and its additional files).

References

Kadereit JW, Baldwin BG. Western Eurasian-western north American disjunct plant taxa: the dry-adapted ends of formerly widespread north temperate Mesic lineages-and examples of long-distance dispersal. Taxon. 2012;61:3–17.

Ruhfel BR, Bove CP, Philbrick CT, Davis CC. Dispersal largely explains the gondwanan distribution of the ancient tropical clusioid plant clade. Am J Bot. 2016;103:1117–28.

Jordano P. What is long-distance dispersal? And a taxonomy of dispersal events. J Ecol. 2017;105:75–84.

Alsos IG, Eidesen PB, Ehrich D, Skrede I, Westergaard K, Jacobsen GH, et al. Frequent long-distance plant colonization in the changing Arctic. Science 80. 2007;316:1606–9. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1139178.

Muñoz J, Felicísimo AM, Cabezas F, Burgaz AR, ILB M. Wind as a long-distance dispersal vehicle in the Southern Hemisphere. Science (80- ). 2004;304:1144–7.

Nathan R. Long-Distance Dispersal of Plants. Science (80- ). 2006;313:786–8. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1124975.

Viana DS, Gangoso L, Bouten W, Figuerola J. Overseas seed dispersal by migratory birds. Proc R Soc B Biol Sci. 2015;283 i:20152406.

Crisp MD, Arroyo MTK, Cook LG, Gandolfo MA, Jordan GJ, McGlone MS, et al. Phylogenetic biome conservatism on a global scale. Nature. 2009;458:754–6.

Drummond CS, Eastwood RJ, Miotto STS, Hughes CE. Multiple continental radiations and correlates of diversification in Lupinus (Leguminosae): testing for key innovation with incomplete taxon sampling. Syst Biol. 2012;61:443–60. https://doi.org/10.1093/sysbio/syr126.

Uribe-Convers S, Tank DC. Shifts in diversification rates linked to biogeographic movement into new areas: an example of a recent radiation in the Andes. Am J Bot. 2015;102:1854–69. https://doi.org/10.3732/ajb.1500229.

Nürk NM, Michling F, Linder HP. Are the radiations of temperate lineages in tropical alpine ecosystems pre-adapted? Glob Ecol Biogeogr. 2018;27:334–45. https://doi.org/10.1111/geb.12699.

Donoghue MJ, Edwards EJ. Biome shifts and niche evolution in plants. Annu Rev Ecol Evol Syst. 2014;45:547–72. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-ecolsys-120213-091905.

Mugrabi de Kuppler AL, Fagúndez J, Bellstedt DU, EGH O, Léon J, Pirie MD. Testing reticulate versus coalescent origins of Erica lusitanica using a species phylogeny of the northern heathers Ericeae, Ericaceae. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2015;88:121–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2015.04.005.

McGuire AF, Kron KA. Phylogenetic relationships of European and African ericas. Int J Plant Sci. 2005;166:311–8. https://doi.org/10.1086/427478.

Kowalski R, Fagúndez J. Maiella miocaenica gen. Et sp. nov., a new heather genus Ericeae, Ericaceae from the central European Miocene. Int J Plant Sci. 2017;178:411–20. https://doi.org/10.1086/691461.

Pirie MD, Oliver EGH, Mugrabi de Kuppler A, Gehrke B, Le Maitre NC, Kandziora M, et al. The biodiversity hotspot as evolutionary hot-bed: spectacular radiation of Erica in the Cape Floristic Region. BMC Evol Biol. 2016;16:190. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12862-016-0764-3.

White F. The history of the Afromontane archipelago and the scientific need for its conservation. Afr J Ecol. 1981;19:33–54.

Oliver EGH, Ericaceae. In: Manning JC, Goldblatt P, editors. Plants of the Greater Cape Floristic Region, Volume 1: The Core Cape Flora. Pretoria: South African National Biodiversity Institute (SANBI Publishing); 2012. p. 482–511.

Ojeda F. Biogeography of seeder and resprouter Erica species in the cape floristic region—where are the resprouters? Biol J Linn Soc. 1998;63:331–47. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1095-8312.1998.tb01521.x.

Galley CC, Bytebier B, Bellstedt DU, Linder HP. The cape element in the Afrotemperate flora: from cape to Cairo? Proc R Soc B Biol Sci. 2007;274:535–43. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2006.0046.

Gizaw A, Brochmann C, Nemomissa S, Wondimu T, Masao CA, Tusiime FM, et al. Colonization and diversification in the African ‘sky islands’: insights from fossil-calibrated molecular dating of Lychnis Caryophyllaceae. New Phytol. 2016;211:719–34.

Chala D, Zimmermann NE, Brochmann C, Bakkestuen V. Migration corridors for alpine plants among the ‘sky islands’ of eastern Africa: do they, or did they exist? Alp Bot. 2017;127:133–44. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00035-017-0184-z.

Mairal M, Sanmartín I, Pellissier L. Lineage-specific climatic niche drives the tempo of vicariance in the Rand Flora. J Biogeogr. 2017;44:911–23. https://doi.org/10.1111/jbi.12930.

Bellstedt DU, Galley C, Pirie MD, Linder HP. The migration of the Palaeotropical arid Flora: Zygophylloideae as an example. Syst Bot. 2012;37:951–9. https://doi.org/10.1600/036364412X656608.

Sanmartín I, Anderson CL, Alarcon M, Ronquist F, Aldasoro JJ. Bayesian island biogeography in a continental setting: the Rand Flora case. Biol Lett. 2010;6:703–7. https://doi.org/10.1098/rsbl.2010.0095.

Pokorny L, Riina R, Mairal M, Meseguer AS, Culshaw V, Cendoya J, et al. Living on the edge: timing of Rand Flora disjunctions congruent with ongoing aridification in Africa. Front Genet. 2015;6:154. https://doi.org/10.3389/fgene.2015.00154.

Verdcourt B. The arid corridor between the north-east and south-west areas of Africa. In: van Zinderen Bakker EM, editor. Paleoecology of Africa. Cape Town: Balkema; 1969. p. 140–4.

White F. The vegetation of Africa: a descriptive memoir to accompany the UNESCO/AETFAT/UNSO vegetation map of Africa. Nat Resour Res. 1983;20:1–356.

Galbany-Casals M, Unwin M, Garcia-Jacas N, Smissen RD, Susanna A, Bayer RJ. Phylogenetic relationships in Helichrysum Compositae: Gnaphalieae and related genera: incongruence between nuclear and plastid phylogenies, biogeographic and morphological patterns, and implications for generic delimitation. Taxon. 2014;63:608–24.

Nürk NM, Uribe-Convers S, Gehrke B, Tank DC, Blattner FR. Oligocene niche shift, Miocene diversification cold tolerance and accelerated speciation rates in the St. John’s Worts Hypericum, Hypericaceae. BMC Evol Biol. 2015;15(80). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12862-015-0359-4.

Míguez M, Gehrke B, Maguilla E, Jiménez-Mejías P, Martín-Bravo S. Carex sect. Rhynchocystis Cyperaceae: a Miocene subtropical relict in the Western Palaearctic showing a dispersal-derived Rand Flora pattern. J Biogeogr. 2017;44:2211–24.

Knox EB, Palmer JD. Chloroplast DNA evidence on the origin and radiation of the giant lobelias in eastern Africa. Syst Bot. 1998;23:109–49.

Fernández-Palacios JM, De Nascimento L, Otto R, Delgado JD, García-Del-Rey E, Arévalo JR, et al. A reconstruction of Palaeo-Macaronesia, with particular reference to the long-term biogeography of the Atlantic island laurel forests. J Biogeogr. 2011;38:226–46.

García-Aloy S, Vitales D, Roquet C, Sanmartín I, Vargas P, Molero J, et al. North West Africa as a source and refuge area of plant biodiversity: a case study on Campanula kremeri and Campanula occidentalis. J Biogeogr. 2017;44:2057–68.

Kim SC, McGowen MR, Lubinsky P, Barber JC, Mort ME, Santos-Guerra A. Timing and tempo of early and successive adaptive radiations in Macaronesia. PLoS One. 2008;3:1–7.

Gehrke B, Linder HP. The scramble for Africa: pan-temperate elements on the African high mountains. Proc R Soc B Biol Sci. 2009;276:2657–65. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2009.0334.

Gizaw A, Kebede M, Nemomissa S, Ehrich D, Bekele B, Mirré V, et al. Phylogeography of the heathers Erica arborea and E trimera in the afro alpine sky islands inferred from AFLPs and plastid DNA sequences. Flora Morphol Distrib Funct Ecol Plants. 2013, 208:453–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.flora.2013.07.007.

Linder HP, Antonelli A, Humphreys AM, Pirie MD, Wüest RO. What determines biogeographical ranges? Historical wanderings and ecological constraints in the danthonioid grasses. J Biogeogr. 2013;40:821–34.

Higgins SI, Richardson DM. Predicting plant migration rates in a changing world: the role of long-distance dispersal. Am Nat. 1999;153:464–75. https://doi.org/10.1086/303193.

Donoghue MJ. Colloquium paper: a phylogenetic perspective on the distribution of plant diversity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(Suppl 1):11549–55. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0801962105.

Carvajal-Endara S, Hendry AP, Emery NC, Davies TJ. Habitat filtering not dispersal limitation shapes oceanic island floras: species assembly of the Galápagos archipelago. Ecol Lett. 2017;20:495–504.

Merckx VSFT, Hendriks KP, Beentjes KK, Mennes CB, Becking LE, Peijnenburg KTCA, et al. Evolution of endemism on a young tropical mountain. Nature. 2015;524:347–50.

Pirie MD, Oliver EGH, Bellstedt DU. A densely sampled ITS phylogeny of the cape flagship genus Erica L. suggests numerous shifts in floral macro-morphology. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2011;61:593–601. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2011.06.007.

Stamatakis A. RAxML-VI-HPC: maximum likelihood-based phylogenetic analyses with thousands of taxa and mixed models. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:2688–90.

Tamura K, Battistuzzi FU, Billing-Ross P, Murillo O, Filipski A, Kumar S. Estimating divergence times in large molecular phylogenies. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:19333–8. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1213199109.

Schwery O, Onstein RE, Bouchenak-Khelladi Y, Xing Y, Carter RJ, Linder HP. As old as the mountains: the radiations of the Ericaceae. New Phytol. 2015;207:355–67. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.13234.

Nakazato T, Warren DL, Moyle LC. Ecological and geographic modes of species divergence in wild tomatoes. Am J Bot. 2010;97:680–93.

Anacker BL, Strauss SY. The geography and ecology of plant speciation: range overlap and niche divergence in sister species. Proc R Soc B Biol Sci. 2014;281:20132980. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2013.2980.

Meeus J. Astronomical algorithms. 2nd edition. Willman-Bell; 1999.

Hijmans RJ. raster: Geographic data analysis and modeling. [R package]. 2015.

R Development Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. 2013. http://www.r-project.org/.

Dray S, Dufour AB. The ade4 Package: Implementing the Duality Diagram for Ecologists. J Stat Softw. 2007;22:1–20. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v022.i04

Schoener TW. The Anolis lizards of Bimini: resource partitioning in a complex Fauna. Ecology. 1968;49:704–26. https://doi.org/10.2307/1935534.

Di Cola V, Broennimann O, Petitpierre B, Breiner FT, D'Amen M, Randin C, Engler R, Pottier J, Pio D, Dubuis A, Pellissier L, Mateo RG, Hordijk W, Salamin N, Guisan A. ecospat: an R package to support spatial analyses and modeling of species niches and distributions. Ecography. 2017;40:774–87. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecog.02671.

Broennimann O, Fitzpatrick MC, Pearman PB, Petitpierre B, Pellissier L, Yoccoz NG, et al. Measuring ecological niche overlap from occurrence and spatial environmental data. Glob Ecol Biogeogr. 2012;21:481–97.

Matzke NJ. Probabilistic historical biogeography: new models for founder-event speciation, imperfect detection, and fossils allow improved accuracy and model- testing. Berkeley: University of California; 2013.

Ree RH, Sanmartín I. Conceptual and statistical problems with the DEC+J model of founder-event speciation and its comparison with DEC via model selection. J Biogeogr. 2018;45:741–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/jbi.13173.

Burnham K, Anderson D. Model selection and multimodel inference. 2nd ed. Springer Science & Business Media: New York, Berlin, Heidelberg; 2002. https://doi.org/10.1198/tech.2003.s147.

Paradis E, Claude J, Strimmer K. APE: analyses of Phylogenetics and evolution in R language. Bioinformatics. 2004;20:289–90.

Ree RH, Moore BR, Webb CO, Donoghue MJ. A likelihood framework for inferring the evolution of geographic range on phylogenetic trees. Evolution. 2005;59:2299–311. https://doi.org/10.1554/05-172.1.

Ree RH, Smith SA. Maximum likelihood inference of geographic range evolution by dispersal, local extinction, and cladogenesis. Syst Biol. 2008;57:4–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/10635150701883881.

Matzke NJ. Model selection in historical biogeography reveals that founder-event speciation is a crucial process in island clades. Syst Biol. 2014;63:951–70. https://doi.org/10.1093/sysbio/syu056.

Maddison WP, Maddison DR. Mesquite: a modular system for evolutionary analysis. 2006. http://mesquiteproject.org.

Pirie MD, Humphreys AM, Antonelli A, Galley C, Linder HP. Model uncertainty in ancestral area reconstruction: a parsimonious solution? Taxon. 2012;61:652–64. https://doi.org/10.5167/uzh-64515.

Skeels A, Cardillo M. Environmental niche conservatism explains the accumulation of species richness in Mediterranean-hotspot plant genera. Evolution (N Y). 2017;71:582–94. https://doi.org/10.1111/evo.13179.

Zachos J, Pagani M, Sloan L, Thomas E, Billups K. Trends, rhythms, and aberrations in global climate 65 Ma to present. Science (80- ). 2001;292:686–93. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1059412.

Marlow JR, Lange CB, Wefer G, Rosell-Mele A. Upwelling intensification as part of the Pliocene-Pleistocene climate transition. Science (80- ). 2000;290:2288. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.290.5500.2288.

Dupont LM, Linder HP, Rommerskirchen F, Schefuß E. Climate-driven rampant speciation of the cape flora. J Biogeogr. 2011;38:1059–68. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2699.2011.02476.x.

Verboom GA, Archibald JK, Bakker FT, Bellstedt DU, Conrad F, Dreyer LL, et al. Origin and diversification of the greater cape flora: ancient species repository, hot-bed of recent radiation, or both? Mol Phylogenet Evol. 2009;51:44–53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ympev.2008.01.037.

Hoffmann V, Verboom GA, Cotterill FPD. Dated plant phylogenies resolve Neogene climate and landscape evolution in the cape floristic region. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0137847. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0137847.

Bytebier B, Antonelli A, Bellstedt DU, Linder HP. Estimating the age of fire in the cape flora of South Africa from an orchid phylogeny. Proc R Soc B Biol Sci. 2011;278:188–95. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2010.1035.

McCarthy T, Rubidge B. The story of earth & life: a southern African perspective on a 4.6 billion-year journey. Cape Town: Struik Publishers; 2005.

Van Wilgen BW, Higgins KB, Bellstedt DU. The role of vegetation structure and fuel chemistry in excluding fire from forest patches in the fire-prone fynbos shrublands of South Africa. J Ecol. 1990;78:210–22.

Gehrke B. Staying cool: preadaptation to temperate climates required for colonising tropical alpine-like environments. PhytoKeys. 2018;96:111–25. https://doi.org/10.3897/phytokeys.96.13353.

Silvertown J. The ghost of competition past in the phylogeny of island endemic plants. J Ecol. 2004;92:168–73.

Désamoré A, Laenen B, Devos N, Popp M, González-Mancebo JM, Carine MA, et al. Out of Africa: north-westwards Pleistocene expansions of the heather Erica arborea. J Biogeogr. 2011;38:164–76. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2699.2010.02387.x.

Meseguer AS. The colonization history of largely isolated habitats. Peer Community Evol Biol. 2019;100065. https://doi.org/10.24072/pci.evolbiol.100065.

Linder HP. The radiation of the cape flora, southern Africa. Biol Rev. 2003;78:597–638. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1464793103006171.

Schnitzler J, Graham CH, Dormann CF, Schiffers K, Peter LH. Climatic niche evolution and species diversification in the cape flora. South Africa J Biogeogr. 2012;39:2201–11. https://doi.org/10.1111/jbi.12028.

Bentley J, Verboom G, Bergh NG. Erosive processes after tectonic uplift stimulate vicariant and adaptive speciation: evolution in an Afrotemperate-endemic paper daisy genus. BMC Evol Biol. 2014;14:27. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2148-14-27.

Acknowledgements

A preprint of this paper has been reviewed and recommended by Peer Community In Evolutionary Biology (https://doi.org/10.24072/pci.evolbiol.100065). Invaluable constructive comments were provided by Andrea Meseguer, Simon Joly, Florian Boucher, and four anonymous reviewers. We thank J. Fagúndez, A. Hitchcock, R. Turner, M. Muasya, C. Stirton, R. Clark, B. Bytebier, M. Pimentel, F. Ojeda, C. Merry, and many others for providing samples and Cape Nature and South Africa National Parks for assistance with permits. We also gratefully acknowledge the computing time granted on the supercomputer Mogon at Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz (www.hpc.uni-mainz.de), and F. Michling for providing R code.

Funding

Funding was provided by the South African National Research Foundation (NRF; DUB and MDP); a postdoctoral fellowship from the Claude Leon Foundation (MDP); DFG (PI1169/1–1, PI1169/1–2, PI1169/2–1 and PI1169/3–1 to MDP); and the Ministerium für Klimaschutz, Umwelt, Landwirtschaft, Natur- und Verbraucherschutz des Landes Nordrhein-Westfalen, the Faculty of Agriculture Lehr- und Forschungsschwerpunkt „Umweltverträgliche und Standortgerechte Landwirtschaft“, Bonn University; and the Landgard foundation (AMK). Any opinion, finding and conclusion or recommendation expressed in this material is that of the authors and the NRF does not accept liability in this regard.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DUB, MDP & EGHO: conceived the research; NCM, AM, MDP, BG, EGHO & DUB: generated data; MDP, MK & NMN: designed analytical approach; MK: performed BioGeoBEARS analyses; NMN: performed GIS-based environmental analyses; MDP: led the writing (to which all authors contributed).

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no financial conflict of interest with the content of this article.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1.

Methods: occurrence data.

Additional file 2.

Methods: Global environmental space, area ranges, and climate similarity analysis.

Additional file 3.

Methods: Biogeographic models; example files for BioGeoBEARS analyses

Additional file 4.

Methods: Selected bootstrap trees used to represent phylogenetic uncertainty between geographically restricted major clades.

Additional file 5.

Methods: Mesquite file used for parsimony ancestral state reconstruction including RAXML bootstrap trees.

Additional file 6

Results: pairwise climate similarity (Schoener’s D) between biogeographic areas per PC axis.

Additional file 7

Results: Pairwise climate similarity (Schoener’s D) between biogeographic areas for combined PC axes.

Additional file 8.

Results of the different models under DEC + J and DEC (generally the better models compared to DIVA-like and BAYAREA-like-models).

Additional file 9.

Results: Summary of event counts from 50 biogeographical stochastic mappings under the best inferred model using the best tree.

Additional file 10.

Results: Number of range-expansion dispersal events (mean and standard deviation of all observed “d” dispersals) averaged across 50 biogeographical stochastic mappings under the best inferred model using the best tree.

Additional file 11.

Results: Number of cladogenetic dispersal events (mean and standard deviation of all observed jump ‘j’ dispersals) averaged from 50 biogeographical stochastic mappings under the best inferred model using the best tree.

Additional file 12.

Results: Number of all dispersal events (mean and standard deviation of all observed anagenetic ‘a’, ‘d’ dispersals, PLUS cladogenetic founder/jump dispersal) averaged from 50 biogeographical stochastic mappings under the best inferred model using the best tree.

Additional file 13.

Results: Ancestral area reconstructions inferred using BioGeoBEARS given the best tree under the best fitting model given A: DEC + J; B: DEC; and without range or dispersal constraint: C: DEC + J; D: DEC. For each model the single most probable state is shown first (boxes with areas at nodes) followed by the relative probability of each state represented with pie charts at nodes. Areas are represented by colours: Dark blue for Europe (E); green for Tropical Africa (T); yellow for Madagascar (M); light blue for Drakensberg (D); red for Cape (C); and further colours for widespread distributions as indicated in the legends.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Pirie, M.D., Kandziora, M., Nürk, N.M. et al. Leaps and bounds: geographical and ecological distance constrained the colonisation of the Afrotemperate by Erica. BMC Evol Biol 19, 222 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12862-019-1545-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12862-019-1545-6