Abstract

Background

Color and pattern phenotypes have clear implications for survival and reproduction in many species. However, the mechanisms that produce this coloration are still poorly characterized, especially at the genomic level. Here we have taken a transcriptomics-based approach to elucidate the underlying genetic mechanisms affecting color and pattern in a highly polytypic poison frog. We sequenced RNA from the skin from four different color morphs during the final stage of metamorphosis and assembled a de novo transcriptome. We then investigated differential gene expression, with an emphasis on examining candidate color genes from other taxa.

Results

Overall, we found differential expression of a suite of genes that control melanogenesis, melanocyte differentiation, and melanocyte proliferation (e.g., tyrp1, lef1, leo1, and mitf) as well as several differentially expressed genes involved in purine synthesis and iridophore development (e.g., arfgap1, arfgap2, airc, and gart).

Conclusions

Our results provide evidence that several gene networks known to affect color and pattern in vertebrates play a role in color and pattern variation in this species of poison frog.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Color and pattern phenotypes have long been of interest to both naturalists and evolutionary biologists [1, 2]. Part of this interest derives from the association of this phenome with selective pressures such as mate choice [3] and predation [4]. Species with morphological phenotypes directly tied to survival and reproduction provide excellent opportunities to study the genetic underpinnings of color and pattern, precisely because these phenotypes are so obviously linked to survival.

Aposematic species rely on color and pattern to warn predators, but in many cases these color and pattern phenotypes are extremely variable, often changing over short geographic distances or even exhibiting polymorphism within populations [5, 6]. Theory has long predicted that aposematic species should be monomorphic because predators learn a common signal, and thus aposematic individuals with a different phenotype should be selected against [2, 7]. While predator variation and drift alone may be sufficient to create phenotypic variation, a variety of alternative selective pressures can act on the aposematic signal to produce and maintain this variety (reviewed in [8]).

Research on the production of color and pattern early in life in polytypic species (those that vary in discrete phenotypes over geographical space) has been limited, especially in vertebrates. Differences in color and pattern in some highly variable aposematic species seem to be determined by a small number of loci [9,10,11,12]. However, the majority of the research on the underlying genetic architecture associated with varied color and patterns in aposematic species has been done in the Neotropical butterflies of the genus Heliconius. While this work has been highly informative, it remains unclear whether these trends are generally applicable to other systems, including in vertebrates.

Many of the Neotropical poison frogs (family Dendrobatidae) exhibit substantial polytypism throughout their range [6, 13]. Despite being one of the better characterized groups of aposematic species, our knowledge of the mechanisms of color production in this family is quite limited. In addition, there is little information on the genetics of color pattern in amphibians generally. While modern genomic approaches, especially high-throughput sequencing, have recently provided extensive insights into the genes underlying color pattern variation in fish [14, 15], reptiles [16], birds [17] and mammals [18,19,20], there have been few genomic studies of the genetic basis of color patterns in amphibians. This is in part because amphibian genomes are often large and repetitive. For example the strawberry poison frog (Oophaga pumilio) has a large genome (6.7 Gb) which is over two-thirds repeat elements [21]. The dearth of amphibian data is an important gap in our knowledge of the genomics of color and pattern evolution, and the genetic and biochemical pathways underlying color pattern variation across vertebrates.

Amphibians exhibit extremely varied colors and patterns, and these are linked to the three structural chromatophore types (melanophores, iridophores, and xanthophores) and the pigments and structural elements found within them (e.g. melanins, guanine platelets, and pteridines; Mills & Patterson 2009). Melanophores and the melanin pigments they contain are responsible for producing dark coloration, particularly browns and blacks, and are also critical to the production of darker green coloration [22]. Blue and green coloration in amphibians is generally produced by reflectance from structural elements in iridophores [23]. Iridophores contain guanine crystals arranged into platelets that reflect particular wavelengths of light, depending on platelet size, shape, orientation and distribution [16, 23, 24]. Generally speaking, thicker and more dispersed platelets reflect longer wavelengths of light [16]. Combinations of iridophores and xanthophores or erythropores containing carotenoids or pteridines (respectively) can produce a wide diversity of colors [16]. Xanthophores are thought to be largely responsible for the production of yellows, oranges, and reds in amphibians. The precise coloration exhibited is linked to the presence of various pigments such as pteridines and carotenoids that absorb different wavelengths of light [22].

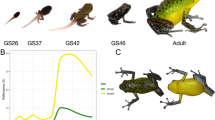

In order to better understand the genetic mechanisms affecting the development of color and pattern, we examined four different captive bred color morphs of the green-and-black poison frog (Dendrobates auratus). The San Felix and super blue morphs both have a brown dorsum, with the former having green spotting, and the latter typically having light blue markings (often circular in shape), sporadically distributed across the dorsum. The microspot morph has a greenish-blue dorsum with small brownish-black splotches across the dorsum. Finally, the blue-black morph has a dark black dorsum with blue markings scattered across the dorsum that are typically long and almost linear. Photographs of frogs from these morphs in captivity are found in Fig. 1. We used an RNA sequencing approach to examine gene expression and characterize the skin transcriptome of this species. In addition to assembling a de novo skin transcriptome of a species from a group with few genomic resources, we compared differential gene expression between color morphs. We focused on differential gene expression in a set of a priori candidate genes that are known to affect color and pattern in a variety of different taxa. Finally, we examined gene ontology and gene overrepresentation of our dataset. These data will provide useful genomic and candidate gene resources to the community, as well as a starting point for other genomic studies in both amphibians and other aposematic species.

Normative depictions of the four captive morphs used in this study. Color morphs clockwise from top left: microspot, super blue, blue and black, San Felix. Microspot and super blue photographs courtesy of ID, blue-black and San Felix photos were provided by Mark Pepper at Understory Enterprises, LLC. Pictures used with permission

Results

Transcriptome assembly

We used the Oyster River Protocol [25] to assemble a transcriptome; this protocol uses a series of different transcriptome assemblers and kmer lengths, ultimately merging them into a single transcriptome. After conducting the Oyster River Protocol for one random individual per color morph and merging them together, we were left with a large transcriptome containing 597,697 transcripts. We examined the BUSCO and transrate scores for each morph’s transcriptome, as well as for the transcriptome created by orthomerging these four assemblies (Table 1). BUSCO and transrate scores were computed using the full, cleaned read dataset from all samples. Given the poor transrate score of our final, merged assembly we selected and used the good contigs from transrate (i.e., those that are accurate, complete, and non-redundant), which had a minimal effect on our overall BUSCO score. In total, our assembly from the good contigs represents 160,613 individual transcripts (the “full assembly” in Table 1). Overall, our annotation to the combined Xenopus, Nanorana, Rana, and UniRef90 peptide databases yielded 76,432 annotated transcripts (47.5% of our transcriptome).

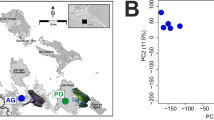

Differential expression and fixed variants

Our results indicate that there are distinct differences in expression between color morphs (Fig. 2). Principal component 1 explained 37.3% of the variation and principal component 2 explained 21.0% of the variation. We successfully mapped 81.6% ± 1.6% of our reads to our reference transcriptome. When we tested for differential expression, we found a total of 2845 differentially expressed transcripts among color morphs (1.77% of our transcriptome; Additional file 1: Table S1). We identified a total of 2172 SNPs on 1151 contigs. Of these, we found 28 SNPs on a contig with an annotated color gene and also alternately fixed among color morphs; these represent 16 unique candidate color genes (Additional file 2: Table S2).

Pathway analyses

From our list of candidate color genes, we found 58 differentially expressed transcripts (q value < 0.05) associated with 41 candidate color genes in total (see Table 2 and Figs. 3 and 4). Many of these genes are involved in typical vertebrate pigmentation pathways, which we highlight in Fig. 5. In our analyses of gene function using all differentially expressed genes in PANTHER, we found that most of these genes were associated with either metabolic or cellular processes (Fig. 6). Similarly, most of these genes contributed to either cell part or organelle cellular components (Fig. 7). The molecular function was heavily skewed towards catalytic activity and binding, both of which are likely a result of the huge developmental reorganization involved in metamorphosis (Fig. 8).

Log-fold expression (transcripts per million) levels of putatively melanin related genes that are differentially expressed between color morphs in Dendrobates auratus. Each individual is represented on the x-axis, and the y-axis represents expression levels for each transcript that annotated to an melanophore-related gene. Genes represented more than once mapped to multiple transcripts. Expression for this heatmap was calculated using transcripts per million in Kallisto, to which we added 1 and log transformed the data (i.e., expression = log(transcripts per million + 1). Microspot and super blue photographs courtesy of ID, blue-black and San Felix photos were provided by Mark Pepper at Understory Enterprises, LLC. Pictures used with permission

Log-fold expression (transcripts per million) levels of putatively iridophore-related genes that are differentially expressed between color morphs in Dendrobates auratus. Each individual is represented on the x-axis, and the y-axis represents expression levels for each transcript that annotated to an iridophore-related gene. Genes represented more than once mapped to multiple transcripts. Expression for this heatmap was calculated using transcripts per million from Kallisto, to which we added 1 and log transformed the data (i.e., expression = log(transcripts per million + 1)). Microspot and super blue photographs courtesy of ID, blue-black and San Felix photos were provided by Mark Pepper at Understory Enterprises, LLC. Pictures used with permission

Discussion

The genetic mechanisms of color variation are poorly known, particularly in amphibians. Here, we address this deficiency by providing some of the first genomic data relevant to color production in amphibians, with a focus on gene expression in the skin during development. Our model system and strategy support the identification of genes likely to regulate color and pattern elements across different morphs of a highly variable species. By combining analyses of differential expression with a targeted search based on an extensive list of candidate genes for developmental control of coloration (approximately 500 genes), we identified multiple genes that were differentially expressed among morphs which have been demonstrated to play important roles in the production of color in other taxa.

We found differential expression of multiple genes in two major suites of color genes, those that influence melanic coloration (black, brown, and grey) and iridophore genes (blue and green coloration). Additionally, we found a few key pteridine pigment genes that are known to influence primarily yellow amphibian coloration that were differentially expressed between morphs. Given that our color morphs had a black versus brown color coupled with either blue or green pattern elements on top of the background, these results seem biologically relevant and indicative of genes that control color and pattern in Dendrobates auratus. As a result, we divide our discussion into three main parts, focusing on the genes that influence dark background coloration, purine synthesis, and iridophore biology. We then discuss a few genes that are part of other pathways (e.g. pteridine synthesis), before proposing genes that have not previously been implicated in the production of color but are plausible candidate genes.

Melanin-related gene expression

Our study frogs have skin with either a black or brown background, both of which are forms of melanic coloration, which provides the basis for contrasting patterns in many vertebrates as well as non-vertebrate taxa [63]. Melanin is synthesized from tyrosine in vertebrates, via the action of a set of key enzymes (e.g., tyrosinase, tyrosinase-like protein 1 and 2). We identified a suite of differentially expressed genes that are involved in the production of melanophores and melanin in this study (Figs. 6 and 8), many of which have been tied to the production of relatively lighter phenotypes in previous studies. Intriguingly, our results parallel similar findings in Oophaga histrionica, a species of poison frog in which mutations in the mc1r gene affecting melanogenesis have produced a lighter, more brownish background in some populations [64]. In a pattern reminiscent of their results, we found that mc1r was only lowly expressed in one super blue frog, and that a variety of other genes linked to lighter phenotypes followed a similar pattern of expression.

For example, many of the differentially expressed color genes in our dataset are active contributors to the tyrosinase pathway (tyrp1, mitf, sox9, lef1, mlph, leo1, adam17, egfr, ednrb). This pathway is enzymatically regulated by tyrosinase as well as other enzymes and cofactors and is key to the production of melanin [65]. The tyrp1 enzyme catalyzes several key steps in the melanogenesis pathway in melanosomes (and melanocytes), has been shown to affect coloration in a wide variety of vertebrates [65, 66], and is important for maintaining the integrity of the melanocytes [67]. In some mammals tyrp1 has been shown to change the relative abundances of the pigments pheomelanin and eumelanin, thereby producing an overall lighter phenotype [68]. Our data mimic this pattern as tryp1 is not expressed in the blue-black morph, and only expressed at low levels in some San Felix individuals. Comparing the photos of the four morphs (Fig. 1), it can readily be seen that blue and black morph has substantially darker (black) background coloration, compared to the other three, which all have a lighter, brownish background coloration. Pheomelanin has only been identified in the skin of one species of frog [69], and it is unclear whether pheomelanin is present outside of mammals and birds. Further, mutations in tyrp1 change melanic phenotypes through different mechanisms in fish (and possibly other ectotherms) than in mammals [66, 70], and the mechanisms by which tyrp1 one affects pigmentation in amphibians are still being elucidated.

The mitf (microphthalmia-associated transcription factor) locus codes for a transcription factor that plays a dominant role in melanogenesis, and has been called the “master regulator” of melanogenesis [71]. In our study, mitf expression was lowest in the microspot population, the population with the least melanic coloration, and most highly expressed in the blue-black morph (although it is worth noting that blue and green colors are also influenced by melanin to some degree). The mitf locus is, itself, targeted by a suite of transcriptional factors including two which were differentially expressed in our dataset: sox9 and lef1. The sox9 gene is upregulated during melanocyte differentiation, can promote melanocyte differentiation, and has been demonstrated to be an important melanocytic transcription factor [72]. Further, sox9 is up-regulated in human skin after UVB exposure and has been demonstrated to increase pigmentation. Sox9 was not expressed in the microspot morph and was only expressed (at a low level) in one San Felix individual. Another important transcription factor is the lymphoid enhancer-binding factor locus (lef1), which mediates Wnt signaling in the context of melanocyte differentiation and development, with important effects on melanogenesis [44]. Upregulation of this gene has been found to reduce synthesis of the darkest melanic pigment eumelanin, resulting in lighter coloration in mink and other vertebrates [44]. In our study, lef1 showed very low expression in the blue and black morph, compared to the other three morphs, indicating that lef1 is a likely contributor to the background dorsal coloration between color morphs in Dendrobates auratus.

Just as mitf is a target of the transcription factors lef1 and sox9, mitf targets endothelin receptors, a type of G Protein Coupled Receptor. Endothelin receptors mediate several crucial developmental processes, particularly the development of neural crest cell populations [73]. Three paralogous families of these receptors have been identified in vertebrates: endothelin receptor B1 (ednrb1), endothelin receptor B2 (ednrb2), and endothelin receptor A (ednra). Ednrb is involved in producing the different male color morphs of the Ruff (a sandpiper), and it is only expressed in black males [17]. In our study, ednrb is not expressed in the blue-black morph, and only one of the ednrb transcripts is expressed in the San Felix morph. Mutations in ednrb1 and ednrb2 have been found to affect pigment cell development (especially melanocytes and iridophores) in a variety of vertebrate species [73]. These receptors show divergent patterns of evolution in the ligand-binding region in African lake cichlids, and appear to have evolved divergently in association with adaptive radiations in this group [15]. The ednrb2 (endothelin receptor B2) locus encodes a transmembrane receptor that plays a key role in melanoblast (a precursor cell of the melanocyte) migration [38]. This receptor interacts with the edn3 ligand. Mutations affecting this ligand/receptor system in Xenopus affect pigment cell development [74].

The leo1 (LEO1 Homolog) and ctr9 (CTR9 Homolog) loci are both components of the yeast polymerase-associated factor 1 (Paf1) complex, which affects the development of the heart, ears and neural crest cells in zebrafish, with dramatic downstream effects on pigment cells and pigmentation, as well as on the Notch signaling pathway [34, 35]. Perhaps unsurprisingly then, we found that notch1, a well-known member of the Notch Signaling Pathway, was differentially expressed between color morphs. Mutations in this gene are known to affect skin, hair and eye pigmentation in humans through effects on melanocyte stem cells [50]. This indicates that notch1 is a good candidate gene for pattern development in poison frogs.

A number of other melanogenesis-related genes were found to be differentially expressed between morphs, such as brca1. Mice with a homozygous mutation of the tumor suppressing brca1 gene show altered coat coloration, often producing a piebald appearance [32]. The precise mechanism behind this is ambiguous, and it may involve either mitf or p53 [33, 75]. Bmpr1b is a bone morphogenic protein which is known to inhibit melanogenesis; when bmpr1b is downregulated via UV exposure it enhances melanin production and leads to darker pigmentation [31]. Some of the other genes (e.g. mlph, or melanophilin) show the same pattern of expression across morphs as lef1, suggesting that multiple genes may contribute to the difference between lighter and darker background coloration in this species. The product of the melanophilin gene forms a complex that combines with two other proteins and binds melanosomes to the cell cytoskeleton, facilitating melanosome transport within the cell. Variants of this gene are associated with “diluted”, or lighter-colored, melanism in a number of vertebrates [47]. Similarly, the mreg (melanoregulin) gene product functions in melanosome transport and hence is intimately involved in pigmentation [49]. Mutations at this locus cause “dilute” pigmentation phenotypes in mice.

In summary, we have found a number of differentially expressed genes that influence melanic coloration which seem to be important between color morphs with a true, black background pattern versus those with a more dilute, brown colored background pattern. Our results parallel similar findings in Oophaga histrionica, a species of poison frog in which mutations in the mc1r gene affecting melanogenesis have produced a lighter, more brownish background in some populations [64]. In addition to mc1r, we have identified a suite of genes with the same expression pattern that are ultimately influenced by mc1r activity; many of these genes have been linked to lighter phenotypes in other taxa.

Purine synthesis and iridophore genes

The bright coloration of D. auratus is confined to the green-blue part of the visual spectrum (with the exception of some brownish-white varieties) in most populations, and thus iridophores are likely to play a role in the color variation displayed across different populations of this species. Higdon et al. (2013) identified a variety of genes that are components of the guanine synthesis pathway and show enriched expression in zebrafish iridophores. A number of these genes (hprt1, ak5, dera, ednrb2, gas1, ikpkg, atic, airc, prtfdc1) were differentially expressed between the different morphs of D. auratus investigated here (Fig. 8). The gart gene codes for a tri-function enzyme that catalyzes three key steps in the de novo purine synthesis pathway [42]. This locus has been associated with critical mutations affecting all three types of chromatophores in zebrafish, through effects on the synthesis of guanine (iridophores), sepiapterin (xanthophores) and melanin (melanocytes) [42]. Zebrafish mutants at this locus can show dramatically reduced numbers of iridophores, resulting in a lighter, or less saturated color phenotype. Similarly, the airc gene plays a critical role in guanine synthesis, and yeast with mutations in this gene leading to aberrant forms of the transcribed protein are unable to synthesize adenine and accumulate a visible red pigment [27, 76]. Similarly, the mthfd (methylenetetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase, cyclohydrolase and formyltetrahydrofolate synthetase 1) gene also affects the de novo purine synthesis pathway [77]. The genes airc, gart, and mthfd had similar expression patterns and were very lowly expressed in the mostly green microspot population. The gene prtfdc1 is highly expressed in iridophores, and encodes an enzyme which catalyzes the final step of guanine synthesis [26]; prtfdc1 had very low expression in the dark blue-black morph, which may be an indication that it plays a role in the reflectance from iridophores. Further, prtfdc1 was highly expressed in the San Felix and super blue morphs, both of which have visible small white ‘sparkles’ on the skin which are likely produced by the iridophores.

How the guanine platelets are formed in iridophores remains an open question. Higdon et al. (2013) proposed that ADP Ribosylation Factors (ARFs) and Rab GTPases are likely to play crucial roles in this context. ARFs are a family of ras-related GTPases that control transport through membranes and organelle structure. We identified one ARF protein (arf6) and two ARF activating proteins (arfgap1 and arfgap2) that were differentially expressed across the D. auratus morphs. We also identified four different Rab GTPases as differentially expressed (rab1a, rab3c, rab3d, rab7a). Mutations at the rabggta (Rab geranylgeranyl transferase, a subunit) locus cause abnormal pigment phenotypes in mice (e.g. “gunmetal”), are known to affect the guanine synthesis pathway [18], and are similarly differentially expressed between color morphs in our dataset. These genes are likely candidates to affect coloration in Dendrobates auratus given that both the green and blue pattern elements are probably iridophore-dependent colors.

Pteridine synthesis

Above we have devoted a large amount of space to melanophore and iridophore related genes. Here we will briefly discuss pteridine synthesis genes, because there is generally less known about them and there are fewer pteridine genes differentially expressed between color morphs in our study. A number of the genes identified as differentially expressed are involved in copper metabolism (sdhaf2, atox1, atp7b). Copper serves as a key cofactor for tyrosinase in the melanogenesis pathway and defects in copper transport profoundly affect pigmentation [28]. Another gene, the xanthine hydrogenase (xdh) locus, was also found to be differentially expressed between morphs, and this gene, which is involved in the oxidative metabolism of purines, affects both the guanine and pteridine synthesis pathways. Additionally, it has been shown to be critically important in the production of color morphs in the axolotl. When xdh was experimentally inhibited axolotls had reduced quantities of a number of pterins, and also showed dramatic differences in color phenotype with xdh-inhibited individuals showing a ‘melanoid’ (black) appearance [62]. Furthermore, xdh deficient frogs show a blue coloration in a species that is typically green [78, 79]. We note here that one xdh transcript showed little (one individual) or no (2 individuals) expression in the bluest morph (blue-black). Similarly, when pigments contained in the xanthophores that absorb blue light are removed, this can lead to blue skin [23]. We also found another gene involved in pteridine synthesis, qdpr (quinoid dihydropteridine reductase), was only expressed in the populations with a lighter blue or green coloration. Mutations in this gene result in altered patterns of pteridine (e.g. sepiapterin) accumulation [53]. We believe that xdh and qdpr are good candidates for variability in coloration in poison frogs.

Fixed genomic variants

Similar to our analysis of differentially expressed color genes, we found a number of SNPs in melanophore and iridophore related genes with alternate fixation among color morphs. For example, the cappuccino gene (cno) is known to effect the maturity of melanosomes and can also dramatically influence the size and number of melanosomes, which produces dramatic changes in phenotypes and can lead to albinism [80]. Intriguingly, cno alleles are alternately fixed between the microspot and San Felix populations, the latter of which has an almost cappuccino-colored background coloration. Similarly, type II iodothyronine deiodinase (dio2) is involved in thyroid hormone conversion, and in flounders it is thought that this conversion promotes pigmentation and prevents albinism [81, 82]. Dio2 is also known to play a role in vision via the pigmentation of the retinal pigment epithelium [83, 84], as are a number of other genes with alternately fixed alleles (rlbp1, ebna1bp2; [85, 86]). Given the close link between eyesight and pigmentation generally, these genes could undergo similar coevolutionary paths in poison frog diversification. We also found fixed differences in prtfdc1, a gene which is responsible for the final step of guanine synthesis and is highly expressed in iridophores [26], and the fixed difference in this gene may be associated with darker versus lighter blue frogs. Another iridophore gene, pgm2 (Phosphoglucomutase-2), had the highest overall number of fixed SNPs in our study (8 SNPs), all of which are fixed differences between the super blue morph and the blue-black/microspot morphs. This gene is highly expressed in iridophores when compared to melanin or retinal pigment epithelium cells [26], so these variants are plausible determinants of blue coloration in Dendrobates auratus. In addition to genes related to pigment production, we also saw fixed genomic variants of genes dealing specifically with patterning. For example, spermidine (srm) exhibited fixed differences between color morphs, and this gene is essential for pigment patterning in zebrafish [87]. Further, we saw fixed differences in two SNPs of the gene rtf1, a gene which is known to interact with the Notch signalling pathway and modulate pigmentation and striping in zebrafish [34]. We also found that notch1 was differentially expressed between color morphs in our dataset. Thus, the combination of srm and rtf1 SNPs and differential expression of notch1 indicate that these genes may play a role in the divergence of pattern elements among color morphs. Most of the color morph specific SNPs we found in candidate color genes appear to produce non-synonymous changes in the amino acid sequence. In fact, every color gene with a fixed difference in SNPs had at least one non-synonymous change except for pts and dio2, the latter of which we were unable to find a matching amino acid sequence for. This provides further evidence that these morph-specific fixed variants are contributing to color and pattern differences in Dendrobates auratus. These fixed, non-synonymous changes also indicate that these genes may be under positive selection to be maintained within color morphs. However, the possibility remains that patterns of alternate fixation of alleles in our inter-population comparisons are due to genetic drift, or selection on alleles due to their impact on traits other than pigmentation.

Novel candidate genes for coloration

In addition to those genes that have previously been linked to coloration which we have identified in our study, we would like to propose several others as candidate color genes, based on their expression patterns in our data. Although most research on blue coloration focuses on light reflecting from iridophores, this has generally not been explicitly tested and there is some evidence that blue colors may arise through different mechanisms (reviewed in [23]). In particular, there is evidence that blue in amphibians can come from the collagen matrix in the skin, as grafts in which chromatophores failed to thrive show a blue coloration [23]. Furthermore, keratinocytes surround melanocytes, and they play a key role in melanosome transfer [88]. In light of this evidence, we propose a number of keratinocyte and collagen genes which are differentially expressed in our dataset as further candidate genes for coloration. Amongst these are krt12, and krt8, col1a1, col5a1, and col14a1. Indeed, alleles of one of these genes, krt8, are differentially fixed between color morphs. These genes, and those like them, may be playing a critical role in coloration in these frogs.

Conclusion

The mechanisms that produce variation in coloration in both amphibians and aposematic species are poorly characterized, particularly in an evolutionary context. Here we have taken a transcriptomics-based approach to elucidating the genetic mechanisms underlying color and pattern development in a poison frog. We found evidence that genes characterizing the melanin and iridophore pathways are likely the primary contributors to color and pattern differences in this aposematic species. Additionally, a handful of genes which contribute to the pteridine pathway seem to be playing a role in differential color production as well. However, the specific mechanisms by which these genes work, as well as how they interact to produce color phenotypes, remains an outstanding issue given the complex nature of each of these pathways. Still, our data indicate that genes involved at every step along the melanin and iridophore pathways from chromatophore production, through pigmentation production and deposition, influence differences in coloration between these morphs. These results make sense in the context of the overall color and pattern of these frogs, and provide a number of promising starting points for future investigations of the molecular, cellular and physiological mechanisms underlying coloration in amphibians.

Methods

Color morphs

Captive bred Dendrobates auratus were obtained from Understory Enterprises, LLC. We note that the breeding stock of these different morphs, while originally derived from different populations in Central America, have been bred in captivity for many generations. As a result, it is possible that color pattern differences between these morphs in captivity may exceed those generally found in the original populations. Nevertheless, the differences between these morphs are well within the range of variation in this highly variable, polytypic species which ranges from Eastern Panama to Nicaragua.

Sample collection

Frogs were maintained in pairs in 10 gal tanks with coconut shell hides and petri dishes were placed under the coconut hides to provide a location for females to oviposit. Egg clutches were pulled just prior to hatching and tadpoles were raised individually in ~ 100 mL of water. Tadpoles were fed fish flakes three times a week, and their water was changed twice a week. Froglets were sacrificed during the final stages of aquatic life (Gosner stages 41–43; [89]). At this point, froglets had both hind limbs and at least one forelimb exposed. These froglets had color and pattern elements at this time, but pattern differentiation and color production is still actively occurring during metamorphosis and afterwards. Individuals were anesthetized with 20% benzocaine gel applied to the venter, followed by double pithing to ensure death. After euthanasia, whole specimens (n = 3 per morph) were placed in RNAlater (Qiagen) for 24 h, prior to storage in liquid nitrogen. We then did a dorsal bisection of each frog’s skin, and prepared half of the skin for RNA extraction.

RNA was extracted from each bisected dorsal skin sample using a hybrid Trizol (Ambion) and RNeasy spin column (Qiagen) method and total RNA quality was assayed using the Bioanalyzer 2100 (Agilent). Messenger RNA (mRNA) was isolated from total RNA with Dynabeads Oligo(dT)25 (Ambion) for use in the preparation of uniquely-barcoded, strand-specific directional sequencing libraries with a 500 bp insert size (NEBNext Ultra Directional RNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina, New England Biosystems). Libraries were placed into a single multiplexed pool for 300 bp, paired end sequencing on the Illumina MiSeq. Each sample had a total of 2–5.8 million reads, as a result sequencing depth is a limiting factor in our analyses.

Transcriptome assembly

We randomly chose one individual per morph type and assembled this individual’s transcriptome. First, we aggressively removed adaptors and did a gentle quality trimming using trimmomatic version 0.36 [90]. We then implemented read error correction using RCorrector version 1.01 [91] and assembled the transcriptome using the Oyster River Protocol version 1.1.1 [25]. Transcriptomes were assembled using Trinity version 2.4.0 [92], two independent runs of SPAdes assembler version 3.11 with kmer lengths of 55 and 75 [93], and lastly Shannon version 0.0.2 with a kmer length of 75 [94]. The four transcriptomes were then merged together using OrthoFuser [25]. Transcriptome quality was assessed using BUSCO version 3.0.1 against the eukaryote database [95] and TransRate 1.0.3 [96]. BUSCO evaluates the genic content of the assembly by comparing the transcriptome to a database of highly conserved genes. Transrate contig scores evaluate the structural integrity of the assembly, and provide measures of accurate, completeness, and redundancy. We then compared the assembled, merged transcriptome to the full dataset (every read in our dataset concatenated together) by using BUSCO and TransRate. We recognize that the data used for transcriptome assembly greatly influences downstream analyses, especially in experimental work in which certain genes may only be expressed in one treatment. However, we did limit the likelihood of this by choosing one individual per color morph. Evidence indicates that our approach did successfully address this issue, as our transcriptome has a very high BUSCO score (> 95%).

Downstream analyses

We annotated our transcriptome using the peptide databases corresponding to frog genomes for Xenopus tropicalis [97], Nanorana parkeri [98], and Rana catesbeiana [99] as well as the UniRef90 database [100] using Diamond version 0.9.10 [101] and an e-value cutoff of 0.001. We then pseudo-aligned reads from each sample using Kallisto version 0.43.0 [102] and examined differential expression of transcripts in R version 3.4.2 [103] using Sleuth version 0.29.0 [104]. Differential expression was analyzed by performing a likelihood ratio test comparing a model with color morph as a factor to a simplified, null model of the overall data, essentially testing for differences in expression patterns between any of the four morphs. In addition to examining overall differential expression between morphs, we examined differential expression in an a priori group of candidate color genes. We used PANTHER [105] to quantify the distribution of differentially expressed genes annotated to Xenopus tropicalis into biological processes, molecular functions, and cellular components. Finally, we used ANGSD for an analysis of SNPs [106]. We only examined SNPs that had a minimum quality score of 20, and a minimum depth of 100 reads. Following SNP calling, we examined SNPS that were fixed in at least one color morph and were in our candidate color gene list. We then used BLAST translated nucleotide to protein searches (tblastx) to align the color morph specific gene variants to the best amino acid sequence match in the model species genome (either Xenopus or Nanorana). We confirmed codon frame by aligning the specific protein sequence from the model species (Xenopus or Nanorana) to the matching translated nucleotide sequence for each candidate gene in D. auratus (except in the case of dio2, for which we were unable to find a matching amino acid sequence). We then determined whether the color morph specific fixed variants produced synonymous or non-synonymous changes or introduced stop codons.

Abbreviations

- adam17:

-

A disintegrin and metalloprotease domain 17

- airc:

-

Phosphoribosylaminoimidazole Carboxylase And Phosphoribosylaminoimidazolesuccinocarboxamide Synthase

- arfgap1:

-

aDP Ribosylation Factor GTPase Activating Protein 1

- arfgap3:

-

aDP Ribosylation Factor GTPase Activating Protein 3

- atic:

-

5-Aminoimidazole-4-Carboxamide Ribonucleotide Formyltransferase/IMP Cyclohydrolase

- atox1:

-

Antioxidant 1 Copper Chaperone

- atp12a:

-

aTPase H+/K+ Transporting Non-Gastric Alpha2 Subunit

- bbs2:

-

Bardet-Biedl Syndrome 2

- bbs5:

-

Bardet-Biedl Syndrome 5

- bmpr1b:

-

Bone morphogenic protein 1

- brca1:

-

Breast And Ovarian Cancer Susceptibility Protein 1

- cno:

-

Cappuccino

- col14a1:

-

Collagen Type XIV Alpha 1 Chain

- col1a1:

-

Collagen Type I Alpha 1 Chain

- col5a1:

-

Collagen Type V Alpha 1 Chain

- ctr9:

-

cTR9 Homolog

- dera:

-

Deoxyribose-Phosphate Aldolase

- dio2:

-

Type II iodothyronine deiodinase

- dtnbp1:

-

Dystrobrevin Binding Protein 1

- edn3:

-

Endothelin 3

- ednrb:

-

Endothelin receptor B2

- egfr:

-

Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor

- fbxw4:

-

f-Box And WD Repeat Domain Containing 4

- gart:

-

Phosphoribosylglycinamide Formyltransferase

- gas1:

-

Growth Arrest Specific 1

- gne:

-

Glucosamine (UDP-N-Acetyl)-2-Epimerase/N-Acetylmannosamine Kinase

- hps3:

-

Hermansky-Pudlak Syndrome 3 Protein

- itgb1:

-

Integrin Subunit Beta 1

- krt12:

-

Keratin 12

- krt8:

-

Keratin 8

- lef1:

-

Lymphoid Enhancer Binding Factor 1

- leo1:

-

lEO1 Homolog

- mc1r:

-

Melanocortin 1 Receptor

- mitf:

-

Microphthalmia-associated transcription factor

- mlph:

-

Melanophilin

- mreg:

-

Melanoregulin

- mthfd1:

-

Methylenetetrahydrofolate dehydrogenase

- notch1:

-

Neurogenic locus notch homolog protein 1

- paf1:

-

Yeast polymerase-associated factor 1

- pgm2:

-

Phosphoglucomutase-2

- prtfdc1:

-

Phosphoribosyl Transferase Domain Containing 1

- pts:

-

6-Pyruvoyltetrahydropterin Synthase

- qdpr:

-

Quinoid dihydropteridine reductase

- qnr-71:

-

quail Neuroretina clone 71

- rab3d:

-

Rab3d, Member RAS Oncogene Family

- rab7a:

-

Rab7a, Member RAS Oncogene Family

- rabggta:

-

Rab geranylgeranyl transferase, a subunit

- scarb2:

-

Scavenger Receptor Class B Member 2

- shroom2:

-

Shroom Family Member 2

- SNP:

-

Single nucleotide polymorphism

- sox9:

-

Sex determining region box 9

- srm:

-

Spermidine

- tbx15:

-

t-Box 15

- tyrp1:

-

Tyrosinase Related Protein 1

- Wnt:

-

Wingless/Integrated

- xdh:

-

Xanthine hydrogenase

References

Bates H. Contributions to an insect fauna of the Amazon valley (Lepidoptera: Heliconidae). Biol J Linn Soc. 1862;23:495–566. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1095-8312.1981.tb01842.x.

Müller F. Ituna and Thyridia: a remarkable case of mimicry in butterflies. Proc Entomol Soc London. 1879;:XX--XXIX.

Kokko H, Brooks R, McNamara JM, Houston AI. The sexual selection continuum. Proc Biol Sci. 2002;269:1331–40.

Ruxton GD, Sherratt TN, Speed MP. Avoiding attack: the evolutionary ecology of crypsis, warning signals and mimicry; 2004.

Merrill RM, Dasmahapatra KK, Davey JW, Dell’Aglio DD, Hanly JJ, Huber B, et al. The diversification of Heliconius butterflies: what have we learned in 150 years? J Evol Biol. 2015;28:1417–38.

Brown JL, Twomey E, Amezquita A, DeSouza MB, Caldwell J, Lötters S, et al. A taxonomic revision of the Neotropical poison frog genus Ranitomeya (Amphibia: Dendrobatidae). Zootaxa. 2011;3083:1–120.

Mallet J, Joron M. Evolution of diversity in warning color and mimicry: polymorphisms, shifting balance, and speciation. Annu Rev Ecol Syst. 1999;30:201–33.

Briolat ES, Burdfield-steel ER, Paul SC, Katja HR, Seymoure BM, Stankowich T, et al. Diversity in warning coloration : selective paradox or the norm ? 2018.

Martin A, Papa R, Nadeau NJ, Hill RI, Counterman BA, Halder G, et al. Diversification of complex butterfly wing patterns by repeated regulatory evolution of a Wnt ligand. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2012;109:12632–7. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1204800109.

Supple MA, Hines HM, Dasmahapatra KK, Lewis JJ, Nielsen DM, Lavoie C, et al. Genomic architecture of adaptive color pattern divergence and convergence in Heliconius butterflies. Genome Res. 2013;23:1248–57.

Kunte K, Zhang W, Tenger-Trolander A, Palmer DH, Martin A, Reed RD, et al. Doublesex is a mimicry supergene. Nature. 2014;507:229–32. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature13112.

Vestergaard JS, Twomey E, Larsen R, Summers K, Nielsen R. Number of genes controlling a quantitative trait in a hybrid zone of the aposematic frog Ranitomeya imitator. Proc R Soc B. 2015;282:20141950.

Summers K, Cronin TW, Kennedy T. Variation in spectral reflectance among populations of Dendrobates pumilio, the strawberry poison frog, in the Bocas del Toro archipelago. Panama J Biogeogr. 2003;30:35–53.

Ahi EP, Sefc KM. Anterior-posterior gene expression differences in three Lake Malawi cichlid fishes with variation in body stripe orientation. PeerJ. 2017:e4080.

Diepeveen ET, Salzburger W. Molecular characterization of two endothelin pathways in east african cichlid fishes. J Mol Evol. 2011;73:355–68.

Saenko SV, Teyssier J, van der Marel D, Milinkovitch MC. Precise colocalization of interacting structural and pigmentary elements generates extensive color pattern variation in Phelsuma lizards. BMC Biol. 2013;11:105.

Ekblom R, Farrell LL, Lank DB, Burke T. Gene expression divergence and nucleotide differentiation between males of different color morphs and mating strategies in the ruff. Ecol Evol. 2012;2:2485–505.

Suzuki T, Li W, Zhang Q, Novak EK, Sviderskaya EV, Wilson A, et al. The gene mutated in cocoa mice, carrying a defect of organelle biogenesis, is a homologue of the human Hermansky-Pudlak Syndrom-3 gene. Genomics. 2001;78 November:30–7.

Bauer GL, Praetorius C, Schepsky A, Swing DA, Sullivan TNO, Copeland NG, et al. The role of MITF phosphorylation sites during coat color and eye development in mice analyzed by bacterial artificial chromosome transgene rescue. Genetics. 2009;594 October:581–94.

Bennett DC, Lamoreux ML. The color loci of mice – a genetic century. Pigment Cell Res. 2003;16:333–44.

Rogers RL, Zhou L, Chu C, Márquez R, Corl A, Linderoth T, Freeborn L, MacManes MD, Xiong Z, Zheng J, Guo C. Genomic takeover by transposable elements in the strawberry poison frog. Mol Biol Evol. 2018;35(12):2913-27.

Duellman WE, Trueb L. Biology of amphibians. Baltimore: The John Hopkins University Press; 1986.

Bagnara JT, Fernandez PJ, Fujii R. On the blue coloration of vertebrates. Pigment Cell Res. 2007;20:14–26.

Ziegler I. The pteridine pathway in zebrafish: regulation and specification during the determination of neural crest cell-fate. Pigment Cell Res. 2003;16:172–82.

MacManes MD. The Oyster River protocol: a multi-assembler and kmer approach for de novo transcriptome assembly. PeerJ. 2018;6:e5428. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.5428.

Higdon CW, Mitra RD, Johnson SL. Gene expression analysis of zebrafish melanocytes, iridophores, and retinal pigmented epithelium reveals indicators of biological function and developmental origin. PLoS One. 2013;8:e67801.

Tolstorukov II, Efremov BD. Genetic mapping of the yeast Pichia pinus mapping by the tetrad analysis. Genetika. 1984;20:1099–107.

Setty SRG, Tenza D, Sviderskaya EV, Bennett DC, Raposo G, Marks MS. Cell-specific ATP7A transport sustains copper-dependent tyrosinase activity in melanosomes. Nature. 2008;454:1142–6.

Nelson AM, Zhao W, Gilliland KL, Zaenglein AL, Liu W, Thiboutot DM. Early gene changes induced by isotretinoin in the skin provide clues to its mechanism of action. Dermato-endocrinology. 2009;1(2):100-101.

Tayeh MK, Yen HJ, Beck JS, Searby CC, Westfall TA, Griesbach H, et al. Genetic interaction between Bardet-Biedl syndrome genes and implications for limb patterning. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17:1956–67.

Yaar M, Wu C, Park HY, Panova I, Schutz G, Gilchrest BA. Bone morphogenetic protein-4, a novel modulator of melanogenesis. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:25307–14.

Ludwig T, Fisher P, Ganesan S, Efstratiadis A. Tumorigenesis in mice carrying a truncating Brca1 mutation. Genes Dev. 2001;15(10):1188–93.

Tonks ID, Walker GJ, Mould AW, Ferguson B, Keith P, Hayward NK, et al. Brca1 is involved in establishing murine pigmentation in a p53 and developmentally specific manner. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2012;25:530–2. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1755-148X.2012.01009.x.

Akanuma T, Koshida S, Kawamura A, Kishimoto Y, Takada S. Paf1 complex homologues are required for notch-regulated transcription during somite segmentation. EMBO Rep. 2007;8:858–63.

Nguyen CT, Langenbacher A, Hsieh M, Chen JNO. The PAF1 complex component Leo1 is essential for cardiac and neural crest development in zebrafish. Dev Biol. 2010;341:167–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ydbio.2010.02.020.

McMenamin SK, Bain EJ, McCann AE, Patterson LB, Eom DS, Waller ZP, et al. Thyroid hormone-dependent adult pigment cell lineage and pattern in zebrafish. Science (80-). 2014;345:1–5.

Wei ML. Hermansky-Pudlak syndrome: a disease of protein trafficking and organelle function. Pigment Cell Res. 2006;19:19–42.

Kelsh RN, Harris ML. Colanesi S, Erickson C a. Stripes and belly-spots – a review of pigment cell morphogenesis in vertebrates. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2009;20:90–104.

Hirobe T. How are proliferation and differentiation of melanocytes regulated? Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2011;24:462–78.

Kawakami K, Amsterdam A, Shimoda N, Becker T, Mugg J, Shima A, et al. Proviral insertions in the zebrafish hagoromo gene , encoding an F-box / WD40-repeat protein , cause stripe pattern anomalies. Curr Biol. 2000;10:463–6.

Ahi EP, Sefc KM. A gene expression study of dorso-ventrally restricted pigment pattern in adult fins of Neolamprologus meeli , an African cichlid species. Peer J. 2017;5:e2843. https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.2843.

Ng A, Uribe RA, Yieh L, Nuckels R, Gross JM. Zebrafish mutations in gart and paics identify crucial roles for de novo purine synthesis in vertebrate pigmentation and ocular development. Development. 2009;136:2601–11. https://doi.org/10.1242/dev.038315.

Nie C, Zhang Z, Zheng J, Sun H, Ning Z, Xu G. Genome-wide association study revealed genomic regions related to white / red earlobe color trait in the Rhode Island Red chickens. BMC Genet. 2016:1–7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12863-016-0422-1.

Song X, Xu C, Liu Z, Yue Z, Liu L, Yang T, et al. Comparative transcriptome analysis of mink (Neovison vison) skin reveals the key genes involved in the melanogenesis of black and white coat colour. Sci Rep. 2017;7:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-017-12754-0.

Johnson SL, Africa D, Walker C, Weston JA. Genetic control of adult pigment stripe development in zebrafish. Dev Biol. 1995;197:27–33.

Levy C, Khaled M, Fisher DE. MITF : master regulator of melanocyte development and melanoma oncogene. Trends Mol Med. 2006;12:406–14.

Cirera S, Markakis MN, Christensen K, Anistoroaei R. New insights into the melanophilin (MLPH) gene controlling coat color phenotypes in American mink. Gene. 2013;527:48–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gene.2013.05.047.

Field MS, Anderson DD, Stover PJ. Mthfs is an essential gene in mice and a component of the purinosome. 2011;2 June:1–13.

Wu XS, Martina JA, Hammer JA. Melanoregulin is stably targeted to the melanosome membrane by palmitoylation. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2012;426:209–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.08.064.

Schouwey K, Beermann F. The notch pathway: hair graying and pigment cell homeostasis. Histol Histopathol. 2008;23:609–16.

Schouwey K, Delmas V, Larue L, Zimber-Strobl U, Strobl LJ, Radtke F, et al. Notch1 and Notch2 receptors influence progressive hair graying in a dose-dependent manner. Dev Dyn. 2007;236:282–9.

Xu F, Sudo Y, Sanechika S, Yamashita J, Shimaguchi S, Honda S, et al. Disturbed biopterin and folate metabolism in the Qdpr -deficient mouse. FEBS Lett. 2014;588:3924–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.febslet.2014.09.004.

Ponzone A, Spada M, Ferraris S, Dianzani I, De Sanctis L. Dihydropteridine reductase deficiency in man: from biology to treatment. Med Res Rev. 2004;24:127–50.

Turque N, Denhez F, Martin P, Planque N, Bailly M, Begue A, et al. Characterization of a new melanocyte-specific gene (QNR-71) expressed in v-myc-transformed quail neuroretina. EMBO J. 1996;15:3338–50.

Planque N, Turque N, Opdecamp K, Bailly M, Martin P, Saule S. Expression of the microphthalmia-associated basic helix-loop-helix leucine zipper transcription factor Mi in avian neuroretina cells induces a pigmented phenotype. Cell Growth Differ. 1999;10:525–36.

Swank RT, Jiang SY, Reddington M, Conway J, Stephenson D, McGarry MP, et al. Inherited abnormalities in platelet organelles and platelet formation and associated altered expression of low molecular weight guanosine triphosphate-binding proteins in the mouse pigment mutant gunmetal. Blood. 1993;81:2626–35.

Fairbank PD, Lee C, Ellis A, Hildebrand JD, Gross JM, Wallingford JB. Shroom2 (APXL) regulates melanosome biogenesis and localization in the retinal pigment epithelium. Development. 2006;133:4109–18. https://doi.org/10.1242/dev.02563.

Lee C, Le MP, Cannatella D, Wallingford JB. Changes in localization and expression levels of Shroom2 and spectrin contribute to variation in amphibian egg pigmentation patterns. Dev Genes Evol. 2009;219:319–30.

Lee, Chanjae, Minh-Phuong Le, David Cannatella, and John B. Wallingford. Changes in localization and expression levels of Shroom2 and spectrin contribute to variation in amphibian egg pigmentation patterns. Mol Biol Evol. 2009;219(6):319-30. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1443579.

Candille SI, Van Raamsdonk CD, Chen C, Kuijper S, Chen-Tsai Y, Russ A, et al. Dorsoventral patterning of the mouse coat by Tbx15. PLoS Biol. 2004;2.

Rieder S, Taourit S, Mariat D, Langlois B. Mutations in the agouti ( ASIP ), the extension ( MC1R ), and the brown ( TYRP1 ) loci and their association to coat color phenotypes in horses (Equus caballus). Mamm Genome. 2001;455:450–5.

Thorsteinsdottir S, Frost SK. Pigment cell differentiation: the relationship between pterin content, allopurinol treatment, and the melanoid gene in axolotls. Cell Differ. 1986;19:161–72.

Sköld HN, Aspengren S, Cheney KL, Wallin M. Fish Chromatophores-from molecular motors to animal behavior. Int Rev Cell Mol Biol. 2016;321:171–219. https://doi.org/10.1016/bs.ircmb.2015.09.005.

Posso-Terranova A, Andrés J. Diversification and convergence of aposematic phenotypes: truncated receptors and cellular arrangements mediate rapid evolution of coloration in harlequin poison frogs. Evolution (N Y). 2017;71:2677–92.

Murisier F, Beermann F. Genetics of pigment cells: lessons from the tyrosinase gene family. Histol Histopathol. 2006;21:567–78.

Braasch I, Liedtke D, Volff JN, Schartl M. Pigmentary function and evolution of tyrp1 gene duplicates in fish. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2009;22:839–50.

Gola M, Czajkowski R, Bajek A, Dura A, Drewa T. Melanocyte stem cells: Biology and current aspects. Med Sci Monit. 2012;18:RA155–9. https://doi.org/10.12659/MSM.883475.

Videira IFDS, Moura DFL, Magina S. Mechanisms regulating melanogenesis. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88:76–83. https://doi.org/10.1590/S0365-05962013000100009.

Wolnicka-Glubisz A, Pecio A, Podkowa D, Kolodziejczyk LM, Plonka PM. Pheomelanin in the skin of Hymenochirus boettgeri (Amphibia: Anura: Pipidae). Exp Dermatol. 2012;21:537–40.

Cal L, Suarez-Bregua P, Cerdá-Reverter JM, Braasch I, Rotllant J. Fish pigmentation and the melanocortin system. Comp Biochem Physiol-Part A Mol Integr Physiol. 2017;211 May:26–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpa.2017.06.001.

Kawakami A, Fisher DE. The master role of microphthalmia-associated transcription factor in melanocyte and melanoma biology. Lab Investig. 2017;97:649–56. https://doi.org/10.1038/labinvest.2017.9.

Cheung M, Briscoe J. Neural crest development is regulated by the transcription factor Sox9. Development. 2003;130:5681–93. https://doi.org/10.1242/dev.00808.

Braasch I, Schartl M. Evolution of endothelin receptors in vertebrates. Gen Comp Endocrinol. 2014;209:21–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ygcen.2014.06.028.

Kawasaki-Nishihara A, Nishihara D, Nakamura H, Yamamoto H. ET3/Ednrb2 signaling is critically involved in regulating melanophore migration in Xenopus. Dev Dyn. 2011;240:1454–66.

Beuret L, Ohanna M, Strub T, Allegra M, Davidson I, Bertolotto C, et al. BRCA1 is a new MITF target gene. Pigment Cell Melanoma Res. 2011;24:725–7.

Sychrova H, Braun V, Souciet J. Molecular cloning and sequence analysis of Zygosaccharomyces rouxii ADE2 gene encoding a phosphoribosyl-aminoimidazole carboxylase. Yeast. 1999;15:1399–402.

Christensen KE, Deng L, Leung KY, Arning E, Bottiglieri T, Malysheva OV, et al. A novel mouse model for genetic variation in 10-formyltetrahydrofolate synthetase exhibits disturbed purine synthesis with impacts on pregnancy and embryonic development. Hum Mol Genet. 2013;22:3705–19.

Frost SK. Developmental aspects of pigmentation in the Mexican leaf frog, Pachymedusa dacnicolor; 1978.

Frost SK, Bagnara JT. Allopurinol-induced Melanism in the Tiger salamander (Ambystoma iigrinum nebulosum). J Exp Zool. 1979;209:455–65.

Gwynn B, Ciciotte SL, Hunter SJ, Washburn LL, Smith RS, Anderson SG, et al. Defects in the cappuccino (cno) gene on mouse chromosome 5 and human 4p cause Hermansky-Pudlak syndrome by an AP-3-independent mechanism. Blood. 2000;96:4227–35.

Tagawa, M. and Aritaki, M. Production of symmetrical flatfish by controlling the timing of thyroid hormone treatment in spotted halibut Verasper variegatus. Gen Comp Endocrinol. 2005;141(2):184-89.

Yoo JH, Takeuchi T, Tagawa M, Seikai T. Effect of thyroid hormones on the stage-specific pigmentation of the Japanese flounder Paralichthys olivaceus: developmental biology. Zool Sci. 2000;17:1101–6. https://doi.org/10.2108/zsj.17.1101.

Glaschke A, Weiland J, Del Turco D, Steiner M, Peichl L, Glosmann M. Thyroid hormone controls cone opsin expression in the retina of adult rodents. J Neurosci. 2011;31:4844–51. https://doi.org/10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6181-10.2011.

Bedolla DE, Torre V. A component of retinal light adaptation mediated by the thyroid hormone cascade. PLoS One. 2011;6:1–9.

Wen B, Li S, Li H, Chen Y, Ma X, Wang J, et al. Microphthalmia-associated transcription factor regulates the visual cycle genes Rlbp1 and Rdh5 in the retinal pigment epithelium. Sci Rep. 2016;6 September 2015:1–9. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep21208.

Amsterdam A, Nissen RM, Sun Z, Swindell EC, Farrington S, Hopkins N. Identification of 315 genes essential for early zebrafish development. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2004;101:12792–7. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0403929101.

Frohnhöfer HG, Geiger-Rudolph S, Pattky M, Meixner M, Huhn C, Maischein H-M, et al. Spermidine, but not spermine, is essential for pigment pattern formation in zebrafish. Biol Open. 2016;5:736–44. https://doi.org/10.1242/bio.018721.

Ando H, Niki Y, Ito M, Akiyama K, Matsui MS, Yarosh DB, et al. Melanosomes are transferred from melanocytes to keratinocytes through the processes of packaging, release, uptake, and dispersion. J Invest Dermatol. 2012;132:1222–9. https://doi.org/10.1038/jid.2011.413.

Gosner KL. A simplified table for staging anuran embryos and larvae with notes on identification. Herpetologica. 1960;16:183–90.

Bolger AM, Lohse M, Usadel B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics. 2014;30:2114–20.

Song L, Florea L. Rcorrector: efficient and accurate error correction for Illumina RNA-seq reads. Gigascience. 2015;4:48. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13742-015-0089-y.

Haas BJ, Papanicolaou A, Yassour M, Grabherr M, Philip D, Bowden J, et al. De novo transcript sequence reconstruction from RNA-Seq: reference generation and analysis with trinity. Nat Protoc. 2014;8:1–43.

Bankevich A, Nurk S, Antipov D, Gurevich AA, Dvorkin M, Kulikov AS, et al. SPAdes: a new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. J Comput Biol. 2012;19:455–77. https://doi.org/10.1089/cmb.2012.0021.

Kannan S, Hui J, Mazooji K, Pachter L, Tse D. Shannon: An information-optimal de novo RNA-seq assembler. bioRxiv. 2016;039230.

Simão FA, Waterhouse RM, Ioannidis P, Kriventseva EV, Zdobnov EM. BUSCO: assessing genome assembly and annotation completeness with single-copy orthologs. Bioinformatics. 2015;31:3210–2.

Smith-Unna R, Boursnell C, Patro R, Hibberd JM, Kelly S. TransRate: reference-free quality assessment of de novo transcriptome assemblies. Genome Res. 2016;26:1134–44.

Coordinators NR. Database resources of the National Center for biotechnology information. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016;44:7–19.

Sun Y-B, Xiong Z-J, Xiang X-Y, Liu S-P, Zhou W-W, Tu X-L, et al. Whole-genome sequence of the Tibetan frog Nanorana parkeri and the comparative evolution of tetrapod genomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2015;112:E1257–62. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1501764112.

Hammond SA, Warren RL, Vandervalk BP, Kucuk E, Khan H, Gibb EA, et al. The north American bullfrog draft genome provides insight into hormonal regulation of long noncoding RNA. Nat Commun. 2017;8:1–8. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-017-01316-7.

Bateman A, Martin MJ, O’Donovan C, Magrane M, Alpi E, Antunes R, et al. UniProt: the universal protein knowledgebase. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:D158–69.

Buchfink B, Xie C, Huson DH. Fast and sensitive protein alignment using DIAMOND. Nat Methods. 2015;12:59–60.

Bray NL, Pimentel H, Melsted P, Pachter L. Near-optimal probabilistic RNA-seq quantification. Nat Biotechnol. 2016;34:525–7.

Team RC. R development Core Team: R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; 2017. http://www.mendeley.com/research/r-language-environment-statistical-computing-96/%5Cnpapers2://publication/uuid/A1207DAB-22D3-4A04-82FB-D4DD5AD57C28

Pimentel H, Bray NL, Puente S, Melsted P, Pachter L. Differential analysis of RNA-seq incorporating quantification uncertainty. Nat Methods. 2017;14:687–90.

Mi H, Huang X, Muruganujan A, Tang H, Mills C, Kang D, et al. PANTHER version 11: expanded annotation data from gene ontology and Reactome pathways, and data analysis tool enhancements. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:D183–9.

Korneliussen TS, Albrechtsen A, Nielsen R. ANGSD: analysis of next generation sequencing data. BMC Bioinformatics. 2014;15:1–13.

Stuckert AMM. Dendrobates auratus skin transcriptome [Data set]. Zenodo. 2018.

Acknowledgments

We thank Evan Twomey and two anonymous reviewers for their in sightful comments on this manuscript.

Funding

Funding for this project was provided by NSF DEB 165536 and an East Carolina University Thomas Harriot College of Arts and Sciences Advancement Council Distinguished Professorship to K Summers. Funding agencies played no role in design, data collection, analysis, or interpretation.

Availability of data and materials

All read data are archived with the European Nucleotide Archive project PRJEB25664. Code for transcriptome assembly, annotation, and downstream analyses are all available on GitHub (https://github.com/AdamStuckert/Dendrobates_auratus_transcriptome). Further, our candidate color genes are available in the Github Repository, and our assembled transcriptome is publicly available [107].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

RR, EM, and KS conceived the project, ID collected samples, KC and EM conducted wet lab work, MM contributed to study design and analyses, AS analyzed the data and wrote the manuscript. All authors have read and approved this manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval

Animal care and use for this research was approved by East Carolina University’s IACUC (AUP #D281).

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Additional files

Additional file 1:

Table S1. Differentially expressed genes. A list of genes that were differentially expressed and relevant test statistics. (CSV 482 kb)

Additional file 2:

Table S2. Fixed genomic variants of color genes. Contig, SNP position, gene name, and whether these changes produce synonymous or non-synonymous changes across color morphs. (CSV 2 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Stuckert, A.M.M., Moore, E., Coyle, K.P. et al. Variation in pigmentation gene expression is associated with distinct aposematic color morphs in the poison frog Dendrobates auratus. BMC Evol Biol 19, 85 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12862-019-1410-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12862-019-1410-7