Abstract

Background

The genetic background of trait variability has captured the interest of ecologists and animal breeders because the genes that control it could be involved in buffering various environmental effects. Phenotypic variability of a given trait can be assessed by studying the heterogeneity of the residual variance, and the quantitative trait loci (QTL) that are involved in the control of this variability are described as variance QTL (vQTL). This study focuses on litter size (total number born, TNB) and its variability in a Large White pig population. The variability of TNB was evaluated either using a simple method, i.e. analysis of the log-transformed variance of residuals (LnVar), or the more complex double hierarchical generalized linear model (DHGLM). We also performed a single-SNP (single nucleotide polymorphism) genome-wide association study (GWAS). To our knowledge, this is only the second study that reports vQTL for litter size in pigs and the first one that shows GWAS results when using two methods to evaluate variability of TNB: LnVar and DHGLM.

Results

Based on LnVar, three candidate vQTL regions were detected, on Sus scrofa chromosomes (SSC) 1, 7, and 18, which comprised 18 SNPs. Based on the DHGLM, three candidate vQTL regions were detected, i.e. two on SSC7 and one on SSC11, which comprised 32 SNPs. Only one candidate vQTL region overlapped between the two methods, on SSC7, which also contained the most significant SNP. Within this vQTL region, two candidate genes were identified, ADGRF1, which is involved in neurodevelopment of the brain, and ADGRF5, which is involved in the function of the respiratory system and in vascularization. The correlation between estimated breeding values based on the two methods was 0.86. Three-fold cross-validation indicated that DHGLM yielded EBV that were much more accurate and had better prediction of missing observations than LnVar.

Conclusions

The results indicated that the LnVar and DHGLM methods resulted in genetically different traits. Based on their validation, we recommend the use of DHGLM over the simpler method of log-transformed variance of residuals. These conclusions can be useful for future studies on the evaluation of the variability of any trait in any species.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Living organisms are under the constant influence of unpredictable changes in the environment. Thus, in ecology as well as in animal and plant breeding, genes that can buffer the negative effects of unpredictable (e.g., diseases) or difficult to avoid (e.g., temperature changes) environmental factors are highly desirable [1]. It is assumed that such genes can control the variation of a trait (at either the population or the individual level) and maintain it at an optimal level [2]. One of the most well-studied genes that is involved in buffering the effects of genetic and environmental factors is the heat-shock protein 90 (Hsp90) gene. In Drosophila and Arabidopsis, Hsp90 is described as a stabilizer of developmental and morphological traits [3,4,5]. This suggests that traditionally applied methods that focus on the genetic control of the mean of traits could be extended by also accounting for the variability around that mean. This is possible since it has been observed that not only the mean of the trait is under genetic control, but also the variation around the mean, which is described in the literature as “variance heterogeneity” or “phenotypic variability”.

Phenotypic variability can be assessed by studying the heterogeneity of residual variance across observations [6]. Empirical evidence that residual variance has a genetic component has been reported for different traits in many animal species [7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15] and in humans [16, 17]. Recently, residual variance has even been linked with filling part of the gap of “missing heritability” in genome-wide association studies (GWAS) in humans [17]. One of the most common methods used to obtain variability phenotype is the double hierarchical generalized linear model (DHGLM) [18]. This rather complex method requires substantial computation time. Thus, to verify the need to use DHGLM, it was compared with simpler approaches: log-transformed variance of a trait [14], log-transformed squared estimated residuals [19], and log-transformed variance of residuals (LnVar) [15]. However, only Sell-Kubiak et al. [14] and Iung et al. [19] reported comprehensive comparative studies. Thus, the extended evaluation would also be needed for LnVar and DHGLM. Furthermore, many studies have reported quantitative trait loci (QTL) that are associated with phenotypic variability, the so-called variance QTL (vQTL) [20]. Detection of vQTL in a population can indicate the presence of an unmodeled interaction associated with the locus [1, 2, 20, 21] or the presence of QTL that directly control the variance of a trait [22, 23]. An overview of selected vQTL that have been detected to date is in Table 1. Still, so far no study has compared the genomic background of variability phenotypes for the same trait obtained with different methods.

In the current study, we continue to focus on the variability of litter size in a Large White population. Litter size is a trait of high economic relevance for pig breeding and has been under intense selection in the past decades. Many reports have shown that litter size has increased from an average of 11.7 live piglets in 2000 to 17.5 in 2019 [24] and this increase has also led to an increase in its variability, which is due to the positive genetic correlation between the mean litter size and its variability [25]. Although litter size might be one of the most studied traits in pigs in terms of genetics, with more than 255 associated single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) reported between 2011 and 2021 [26], to our knowledge, only the Sell-Kubiak et al. [25] study has detected vQTL for litter size in pigs. One of the most promising candidate genes for the variability of litter size is HSPCB, which is better known as the aforementioned Hsp90 [27]. Although our previous study [25] reported the first SNPs associated with phenotypic variability in litter size in pigs, a follow-up study is necessary to confirm more precisely the genomic regions that affect variability in litter size, especially because now we have access to high-density SNP-chip data (660 K instead of 60 K) and the number of genotyped animals has increased exponentially since the publication of our previous paper.

Here, we compare two methods to estimate the phenotypic variability of litter size and to evaluate its genetic background and detect new genomic regions associated with it, by performing a GWAS using genotypes from a high-density SNP-chip. Thus, our study has two main aims: (1) to compare two approaches for obtaining variability phenotypes for litter size, and for analyzing their genetic background, i.e. a simpler log-transformed variance of residuals (LnVar) and a more complex double hierarchical generalized linear model (DHGLM); and (2) to perform a single-SNP GWAS to detect novel genomic regions associated with litter size variability using high-density SNP-chip data on ~ 12,000 Large White pigs. The data used in this study is an updated version of the litter size records and genotypes used in the previous GWAS performed by Sell-Kubiak et al. [25], where only DHGLM was used to obtain variability phenotypes.

Methods

Phenotypes

The phenotypic data on Large White pigs used in this study were collected on multiplication farms of Topigs Norsvin (Vught, the Netherlands) between March 1982 and January 2019. In total, litter size records (total number born, TNB) for over 640,000 litters were available before data editing. Records were removed if TNB was equal to 3 or less, or if only one record per sow was available. Parities 10 + were treated as parity 10 and litters with a TNB larger than 25 were recoded to 25. This allowed us to keep such records in the analysis, rather than removing the most extreme values. After data editing, 607,553 litter records from 121,088 sows were available for further analysis. The average TNB was 13.76 (± 3.64) and the distribution of TNB is presented in Fig. 1. The pedigree contained 168,230 records and was on average five generations deep.

Estimation and analysis of variability phenotypes using the log-transformed variance of residuals

Variability phenotype was obtained as the log-transformed variance of residuals (LnVar) of TNB in two steps. First, to obtain estimates of variance components, the TNB data were analyzed with the following traditional animal model, as previously described and tested by Dobrzański et al. [28], using the ASReml 3.0 package [29]:

where \(\mathbf{y}\) is a vector of phenotypes for TNB; \(\mathbf{X}\), \(\mathbf{Z}\), and \(\mathbf{U}\) are incidence matrices relating phenotypes to effects; \(\mathbf{b}\) is a vector of the fixed effects of herd-year-season and parity; \(\mathbf{a}\) is a vector of additive genetic effects, with \(\mathbf{a}{\sim}{\text{N}}\left({\mathbf{0}},\mathbf{A}{\sigma }_{{a}}^{2}\right)\), where \(\mathbf{A}\) is the augmented numerator relationship matrix and \({\sigma }_{{a}}^{2}\) is the additive genetic variance; \(\mathbf{p}\mathbf{e}\) is a vector of permanent environmental sow effects, which accounts for repeated observations per sow, with \(\mathbf{p}\mathbf{e}{\sim }{\text{N}}\left({\mathbf{0}},{\mathbf{I}}_{\mathrm{pe}}{\sigma }_{{pe}}^{2}\right),\) where \({\mathbf{I}}_{\mathrm{pe}}\) is the appropriate identity matrix and \({\sigma }_{{pe}}^{2}\) is the permanent environmental sow variance; and \(\mathbf{e}\) is a vector of residuals, with \(\mathbf{e}{\sim}{\text{N}}\left({\mathbf{0}},{\mathbf{I}}_{\mathrm{e}}{\sigma }_{{e}}^{2}\right)\), where \({\mathbf{I}}_{\mathrm{e}}\) is the appropriate identity matrix and \({\sigma }_{{e}}^{2}\) is the residual variance.

In the second step, estimates of the residuals from the first step were used to estimate the phenotype for the log of variability of TNB (LnVarTNB) for each sow as the within-individual variance of residuals and log-transforming the result. Log transformation was used to normalize the distribution of the variability phenotypes and to assume an exponential model for the environmental variance [8, 30,31,32], which in general is described as: \({y}_{i}=\mu +u+\mathrm{exp}\left(\frac{1}{2}\left(\eta +v\right)\right){\epsilon }_{j}\,{\text{for}}\,j=1,\dots n\), where \({y}_{i}\) are the phenotypic observations for LnVarTNB, \(\mu\) is the population mean, \(\eta\) is the log environmental variance mean; \(u\) and \(v\) are the genetic values of the mean and environmental variance, respectively, following \(\left[\begin{array}{c}u\\ v\end{array}\right]{\sim}\text{ N}\left({\mathbf{0}},\left[\begin{array}{cc}{\sigma }_{{u}}^{2}& {\sigma }_{{u,v}}\\ {\sigma }_{{u,v}}& {\sigma }_{{v}}^{2}\end{array}\right]\right)\), where \({\sigma }_{{u}}^{2}\) and \({\sigma }_{{v}}^{2}\) are the genetic variances and \({\sigma }_{{u,v}}\) is the covariance between the genetic effects; and \({\epsilon }_{j}\) refers to independent, identically and normally distributed variables, that are independent from \(u\) and \(v\).

The variability phenotypes from LnVar were analyzed with the following model, as previously used by Berghof et al. [15] and Dobrzański et al. [28]:

where \({\mathbf{y}}_{\mathbf{v}\mathbf{a}\mathbf{r}}\) is a vector of LnVarTNB phenotypes; \({\mathbf{X}}_{\mathbf{v}\mathbf{a}\mathbf{r}}\) and \({\mathbf{Z}}_{\mathbf{v}\mathbf{a}\mathbf{r}}\) are incidence matrices relating phenotypes to model effects; \({\mathbf{b}}_{\mathbf{v}\mathbf{a}\mathbf{r}}\) is a vector of the fixed effects of farm-year-season of the first farrowing; \({\mathbf{a}}_{\mathbf{v}\mathbf{a}\mathbf{r}}\) is a vector of additive genetic effects, with \({\mathbf{a}}_{\mathbf{v}\mathbf{a}\mathbf{r}}{\sim}\text{ N}\left({\mathbf{0}},\mathbf{A}{\sigma }_{\text{avar}}^{2}\right)\), where \({\sigma }_{\text{avar}}^{2}\) is the additive genetic variance; and \({\mathbf{e}}_{\mathbf{v}\mathbf{a}\mathbf{r}}\) is a vector of residuals, with \({\mathbf{e}}_{\mathbf{v}\mathbf{a}\mathbf{r}}{\sim}\text{ N}\left({\mathbf{0}},{\mathbf{I}}_{\mathrm{evar}}{\sigma }_{\text{evar}}^{2}\right)\), where \({\mathbf{I}}_{\mathrm{evar}}\) is the appropriate incidence matrix and \({\sigma }_{\text{evar}}^{2}\) is the residual variance. To account for differences in residual variance due to the varying numbers of TNB records available per sow, we estimated a unique residual variance for each of the nine groups of sows based on numbers of records (Group 1: 19,670 sows with two litters; Group 2: 18,173 sows with three litters; Group 3: 17,601 sows with four litters; Group 4: 16,868 sows with five litters; Group 5: 15,661 sows with six litters; Group 6: 13,365 sows with seven litters; Group 7: 9516 sows with eight litters; Group 8: 5581 sows with nine litters; and Group 9: 4188 sows with ten or more litters).

Estimation and analysis of variability using a double hierarchical generalized linear model

We also analyzed the variability of TNB with a double hierarchical generalized linear model (DHGLM) [18, 33], which also allows estimation of variance components for residual variance in ASReml 3.0. The method is based on a bivariate model that requires several iterations until convergence and was used in an earlier study to obtain variability phenotypes for a GWAS for litter size variability [25]. The applied DHGLM was:

where \(\mathbf{y}\) is the vector of phenotypes TNB and \({\varvec{\uppsi}}\) is the vector of response variables for the variance part of the DHGLM; the residuals \(\mathbf{e}\) and \({\mathbf{e}}_{\mathbf{v}}\) are assumed to be independent and normally distributed but with heterogeneous variances across phenotypes; \(\mathbf{b}\) and \({\mathbf{b}}_{\mathbf{v}}\) are vectors of the fixed effects of parity of the sow and farm-year-season of the farrowing for \(\mathbf{y}\) and \({\varvec{\uppsi}}\), respectively; \(\mathbf{a}\) and \({\mathbf{a}}_{\mathbf{v}}\) are vectors of random additive genetic effects for \(\mathbf{y}\) and \({\varvec{\uppsi}}\), with \(\left[\begin{array}{c}{\mathbf{a}}\\ {\mathbf{a}}_{\mathbf{v}}\end{array}\right]{\sim}\text{ N}\left({\mathbf{0}},\left[\begin{array}{cc}{\sigma }_{\text{a}}^{2}& {\sigma }_{\text{a,av}}\\ {\sigma }_{\text{a,av}}& {\sigma }_{\text{av}}^{2}\end{array}\right]\otimes \mathbf{A}\right)\), where \({\sigma }_{\text{av}}^{2}\) is the additive genetic variance, \({\sigma }_{\text{a,av}}\) is the covariance between the genetic effects and \(\otimes\) is the Kronecker product; \(\mathbf{p}\mathbf{e}\) and \(\mathbf{p}{\mathbf{e}}_{\mathbf{v}}\) are vectors of random non-genetic permanent sow effects for \(\mathbf{y}\) and \({\varvec{\uppsi}}\)·, with \(\left[\begin{array}{c}\mathbf{p}\mathbf{e}\\ \mathbf{p}{\mathbf{e}}_{\mathrm{v}}\end{array}\right]{\sim}\text{ N}\left({\mathbf{0}},\left[\begin{array}{cc}{\sigma }_{\text{pe}}^{2}& {\sigma }_{\text{pe,pev}}\\ {\sigma }_{\text{pe,pev}}& {\sigma }_{\text{pev}}^{2}\end{array}\right]\otimes \mathbf{I}\right)\), where \({\sigma }_{\mathrm{pev}}^{2}\) is the permanent sow variance, \({\sigma }_{\text{pe,pev}}\) is the covariance between the permanent sow effects; and \(\mathbf{e}\) and \({\mathbf{e}}_{\mathbf{v}}\) are vectors of residuals, with \(\left[\begin{array}{c}\mathbf{e}\\ {\mathbf{e}}_{\mathrm{v}}\end{array}\right]{\sim}\text{ N}\left(\begin{array}{c}{\mathbf{0}}\\ {\mathbf{0}}\end{array},\left[\begin{array}{cc}{\mathbf{W}}^{-1}{\sigma }_{\mathrm{e}}^{2}& 0\\ 0& {\mathbf{W}}_{\mathrm{v}}^{-1}{\sigma }_{\text{ev}}^{2}\end{array}\right]\right)\), where \(\mathbf{W}={\text{diag}}\left({\text{exp}}{\left(\stackrel{\wedge }{\uppsi }\right)}^{-1}\right)\) and \({\mathbf{W}}_{\mathrm{v}}={\text{diag}}\left(\frac{1-h}{2}\right)\) are expected reciprocals of the residual variance from the previous iteration, and \({\sigma }_{\mathrm{e}}^{2}\) and \({\sigma }_{\text{ev}}^{2}\) are scaling variances and are expected to be equal to 1 [31]. The predicted residual variance for each TNB phenotype \({\text{exp}}\left(\stackrel{\wedge }{\uppsi }\right)\) is based on the estimated fixed and random effects for \({\varvec{\uppsi}}\) in the previous iteration of the algorithm. This methodology produced the second variability phenotype—varTNB and estimated its variance components.

Note: to fully evaluate the genetic variation within litter size variability based on LnVar and DHGLM, the genetic coefficient of variation on the standard deviation (SD) level (\({\mathrm{GCV}}_{\mathrm{SDe}}\)) was used, which can be approximated as: \({\mathrm{GCV}}_{\mathrm{SDe}}=\frac{{\upsigma }_{\mathrm{addv}}\left({\sigma }_{\mathrm{e}}\right)}{\overline{{\sigma }_{\mathrm{e}}}}\approx \frac{1}{2}{\sigma }_{\mathrm{avar}}\) or \(\approx \frac{1}{2}{\sigma }_{\mathrm{av}}\), where \({\upsigma }_{\mathrm{addv}}\) is the genetic SD in residual variance.

Comparison of the LnVar and DHGLM

The two methods used to estimate variability phenotypes for litter size, i.e. LnVar and DHGLM, were evaluated by:

-

(1)

Comparing the estimates of variance components and the estimated breeding values (EBV) of LnVarTNB and varTNB and their theoretical accuracies which were estimated based on the following equation: \({r}_{A,I}=\sqrt{1-\frac{{s}_{i}}{{\sigma }_{\mathrm{add}}^{2}}}\), where \({s}_{i}\) is the standard error for the EBV of the \(i\)th individual and \({\sigma }_{\mathrm{add}}^{2}\) is the additive genetic variance for the trait.

-

(2)

Three-fold cross-validation used to predict EBV for LnVarTNB and varTNB. For this, we selected paternal families with at least three half-sisters with litter size records. Then, phenotypes for one of the paternal half-sisters were set to missing, which resulted in removing 3650 sows and their records in three subsets of data. This cross-validation imitates a situation where a breeding program aims at predicting the phenotype of a new-born sow that already has paternal half-sisters with litter size records. The predicted EBV were then correlated with the log-transformed variance of litter size per sow. A similar validation approach was described by Sell-Kubiak et al. [14].

SNP genotypes for GWAS

In total, 12,232 genotyped sows (N = 11,451) and boars (N = 781) were available for the GWAS. Genotyping was performed at GeneSeek (Lincoln, NE, USA) using three medium-density SNP chips. Most animals (N = 7079) were genotyped using the (Illumina) GeneSeek custom 50K SNP chip (Lincoln, NE, USA), while 3276 and 1877 animals were genotyped using the (Illumina) GeneSeek custom 80K SNP chip (Lincoln, NE, USA) and the Illumina Porcine SNP60 Beadchip (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA), respectively. In total, 499 animals that had already been genotyped with the medium-density chips were also genotyped with the Axiom porcine 660K array from Affymetrix (Affymetrix Inc., Santa Clara, CA, USA) at GeneSeek (Lincoln, NE, USA). These animals were the sires with the largest number of offspring in the genotyped dataset.

Quality control of the genotype data included exclusion of SNPs with a GenCall score < 0.15 (Illumina Inc., 2005), a call rate < 0.95, and a minor allele frequency < 0.01, and of the SNPs that deviated strongly from the Hardy–Weinberg equilibrium (χ2 > 600), that were located on sex chromosomes, and that were unmapped. The positions of the SNPs were based on the Sscrofa11.1 assembly of the reference genome. Since all animals had a frequency of missing genotypes ≤ 0.05, none were removed based on that criterion.

After quality control, missing genotypes of the animals genotyped with the (Illumina) GeneSeek custom 50K SNP chip were imputed within the population using the Fimpute v2.2 software [34], while animals genotyped with the other two chips had their genotypes imputed to the set of SNPs on the (Illumina) GeneSeek custom 50K SNP chip that passed the quality control. After quality control and imputation, genotypes on 50,717 SNPs were available and were used in imputation to the 660K genotypes using Fimpute v2.2 [34]. After quality control and imputation, genotypes on 526,505 SNPs were available for the GWAS.

Genome-wide association study

For use in GWAS, the EBV for variability obtained with the two methods were deregressed using the methodology of Garrick et al. [35]. Deregression of EBV avoids double-counting of parental information due to various information sources and complex family structures in a population, and provides phenotypes for boars that do not have own litter size records. This also allows more genotyped animals to be included in the GWAS and thus increase its power to detect QTL.

A single-SNP GWAS was performed using the imputed 660K genotypes and applying the following linear animal model in the GCTA software [36, 37]:

where \({y}_{k}^{*}\) is the deregressed EBV of the \(k\)th animal for LnVarTNB or varTNB; \(\mu\) is the average of the deregressed EBV; \({\mathrm{X}}^{*}\) is the genotype (0, 1, 2) of the \(k\)th animal for the evaluated SNP; \(\widehat{\upbeta }\) is the unknown allele substitution effect of the evaluated SNP; \({u}_{k}^{*}\) is the random additive genetic effect, assumed to be distributed as \(\sim N({\mathbf{0}},\mathbf{G}{\sigma }_{\mathrm{a}}^{2*})\), which accounts for the (co)variances between animals though the formation of a genomic numerator relationship matrix (\(\mathbf{G}\)), constructed using the imputed 660 K genotypes, \({\sigma }_{\mathrm{a}}^{2*}\) is the additive genetic variance; and \({e}_{k}^{*}\) is the random residual effect, which was assumed to be distributed as \(\sim N({\mathbf{0}},\mathbf{I}{\sigma }_{\mathrm{e}}^{2*})\).

The genetic variance explained by a SNP (\({\sigma }_{snp}^{2}=2pq{\widehat{\upbeta }}^{2}\)) was estimated based on the allele frequencies (\(p\) and \(q\)) and the estimated allele substitution effect (\(\widehat{\upbeta }\)). The proportion of phenotypic variance explained by the SNP was defined as \({\sigma }_{snp}^{2}/{\sigma }_{P}^{2}\), where \({\sigma }_{P}^{2}\) is the total phenotypic variance (sum of the additive genetic and residual variances), which was estimated based on the model described above without a SNP effect. Significant SNPs were declared based on a p-value < 10–6, while suggestive SNPs were declared based on a p-value < 10–4 and linkage disequilibrium (LD) with the significant SNP. Each region with the significant and suggestive SNPs was defined as a separate vQTL region.

Following the GWAS based on the imputed 660 K data, we investigated the linkage disequilibrium (LD) in the QTL region on SSC7 that overlapped between the two variability phenotypes. LD, as measured by r2, was calculated between SNPs using the Plink 1.9 software [38].

Search for candidate genes

Based on the GWAS results, we used the location of the significant SNPs to search for candidate genes with the software BIOMART available in Ensembl Sscrofa 11.1 [39] by entering the position of a SNP and ± 50 kb if the SNP was not located within a known gene. Furthermore, the PigQTL database of the Animal Genome project [26] was used to find previously detected associations and QTL related to pig reproduction within the most promising regions. This was done by entering the start and end position of the identified QTL regions for litter size variability.

Results

Comparison of the variability phenotypes

Estimates of the variance components and heritability for total number born (TNB) and its variability are in Table 2. The variance components obtained for the variability of litter size differed between the two estimation methods (LnVar and DHGLM), which resulted in differences between heritability estimates. The genetic coefficient of variation on the SD level (\({\mathrm{GCV}}_{\mathrm{SDe}}\)) indicated a possible change of 9.1 and 9.6% per generation in the genetic SD of LnVarTNB and of varTNB, respectively. Table 3 shows estimates of the correlations between random effects in the DHGLM, with a correlation of 0.43 between additive effects and a correlation of − 0.87 between permanent sow effects.

The correlation between the EBV obtained with the two methods was 0.86, which indicates some reranking of the animals. In the validation, we also compared the EBV from the two methods with those obtained for the variability of litter size by Sell-Kubiak et al. [25], which will be referred to as varTNB_2015. Estimates of the correlation of the EBV for varTNB_2015 with those for LnVarTNB and varTNB were 0.73 and 0.83, respectively. These results suggest that the variability phenotypes obtained with the two methods are not as similar as expected.

The two methods were also compared by evaluating the theoretical accuracies of the EBV and by cross-validation. The theoretical accuracies presented in Fig. 2 indicate that the highest accuracy was reached for varTNB, while LnVarTNB and varTNB_2015 resulted in very similar accuracies, although the older dataset contained fewer records per sow. The results of the three-fold cross-validation indicated that the EBV from DHGLM had a significantly (P = 0.038 based on a t-test) higher precision than the EBV based on LnVar (Table 4).

Theoretical accuracies of EBV for litter size variability in Large White sows for two methods: log-transformed variance of residuals from multiple observations per sow (LnVarTNB) and residual variance of individual litter size obtained with a double hierarchical GLM (varTNB; or varTNB_2015 based on Sell-Kubiak et al. [25]). a LnVarTNB vs. varTNB, b varTNB vs. varTNB_2015, c LnVarTNB vs. varTNB_2015

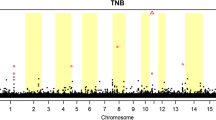

Significant SNPs and candidate genes

Figures 3 and 4 present the GWAS results of this study and Tables 5 and 6 show the significant and suggestive SNPs for each identified vQTL region for LnVarTNB and varTNB, respectively. The estimates of the genetic variance obtained in the GWAS were 0.012 for LnVarTNB and 0.014 for varTNB. The inflation factors (lambda) for both variability phenotypes are in Additional file 1: Fig. S1. Only one identified vQTL region overlapped between LnVarTNB and varTNB, i.e. a region on SSC7, which contained the most significant SNP detected for both variability traits, AX-116689108. This SNP had a low minor allele frequency (MAF = 0.01) with only three animals being homozygous for the least frequent genotype and 253 animals being heterozygous. The least frequent allele was associated with greater litter size variability. This low MAF could be explained by the selection history of the population, with strong selection for increased litter size over the last decades, because greater litter size variation could reduce the average litter size.

Genome-wide association for phenotypic variability of litter size in Large White pigs based on a deregressed EBV of log-transformed residuals (LnVarTNB) for 11,230 genotyped purebred sows and boars, and b a double hierarchical generalized linear model (varTNB) for 12,232 genotyped purebred sows and boars. The dashed grey line on the figure indicates the significance threshold − log10(P-value) ≤ 6

Manhattan plots for the GWAS of phenotypic variability of litter size based on a LnVarTNB, and b varTNB. The y-axis shows the − log10(p-values) of single SNP association with LnVarTNB or varTNB in Large White pigs, and the x-axis shows the physical position of the SNP in the SSC7 vQTL region. Linkage disequilibrium (LD) is given on a scale of 0–1 as a measure of the pairwise correlation between the most significant SNP (pink dot) and all other SNPs

We also investigated the LD between AX-116689108 and its surrounding SNPs to check if the mapping of the most significant SNP was correct. This showed that the highest LD was between AX-116689108 and the SNPs in the vQTL region on SSC7, which confirms that the significant SNP is properly mapped.

Additional vQTL regions were identified on SSC1 and SSC18 for LnVarTNB and on SSC7 and SSC11 for varTNB. These GWAS results provide support for considering the variability phenotypes obtained with the two methods as two different traits, since different genomic regions were identified for each of them.

Based on the positions of the significant and suggestive SNPs for the two variability traits, we identified several candidate genes (see Tables 5 and 6) within ± 50 kb from each SNP. However, not all the significant SNPs were located within a known gene region. This was the case for the most significant SNP detected on SSC7 for both traits and for most of the suggestive SNPs for varTNB. Several previously reported QTL related to reproduction traits in pigs were located within the identified vQTL regions (Tables 5 and 6). Interestingly, SNP AX-116317698 at 38.81 Mb on SSC7 in the vQTL region for variability of litter size was previously found to be associated with TNB (see Additional file 1: Fig. S2 and Additional file 2 Table S1).

Discussion

The main aim of our study was to detect novel genomic regions that are involved in the genetic control of the phenotypic variability of litter size in Large White pigs. In addition to this objective, we also compared two methods to estimate variability phenotypes, i.e. LnVar and DHGLM. This is the second study that reports vQTL for the variability of litter size and the first one to study the genomic differences between variability phenotypes obtained with two methods.

Comparison of methods

We compared the following two methods for estimating litter size variability: the simple approach of estimating log-transformed variance residuals (LnVar) and a DHGLM. The latter was previously used for analysis of part of the same data as used here by Sell-Kubiak et al. [25]. The LnVar is a simpler method than DHGLM to compute variability phenotypes and requires less computation time, making it more suitable for application in breeding programs. The DHGLM method was described in detail by Berghof et al. [15] and Dobrzański et al. [28]. Dobrzański et al. [28] also tested whether accounting for the “parity curve” in litter size, i.e. a change in average litter size in subsequent parities [40], affected the variability phenotype. This was proposed since extending the model to better fit the phenotypic data should, in theory, yield more accurate estimates of the residual variance. However, no differences in residual variance were found when applying these more complex animal models [28].

The DHGLM is an interesting approach to study the variability of traits because it enables analysis of variation even when only one observation per animal is available [14]. This of course comes with a cost, since more observations per animal increases the heritability of trait variability [41]. It is important since trait variability tends to have a very low heritability in the classical sense [6], whereas in exponential models it should be considered as a measure of the reliability of EBV for variability and as such does not reflect the magnitude of the genetic variance (for this, the genetic coefficient of variation on the SD level is used). Due to its complexity, DHGLM was compared with simpler methods: log-transformed variance of birth weight per litter in pigs [14], log-transformed squared estimated residuals of yearling weight in Nellore beef cattle [19], and log-transformed variance of residual of body weight in layer hens (LnVar) [15]. Sell-Kubiak et al. [14] and Berghof et al. [15] reported high similarity between the variability traits obtained with the compared methods, whereas the Iung et al. [19] indicated that DHGLM provided more accurate estimates. However, only Sell-Kubiak et al. [14] and Iung et al. [19] reported comprehensive comparative studies, whereas Berghof et al. [15] merely presented the genetic correlation between traits. Interestingly, in the study of Sell-Kubiak et al. [14] the correlation between EBV for the studied methods (0.88) was slightly higher than that found between LnVar and DHGLM (0.86) in the current study, whereas in the study of Iung et al. [19] the correlation was only 0.45. In those studies, the accuracy of EBV was always higher for DHGLM than for the simpler method.

Overall, our results indicate that the two methods used to estimate variability phenotypes of litter size (LnVar and DHGLM) do not produce identical traits, based on comparing estimates of variance components, estimated breeding values, and theoretical accuracies of EBV and by a three-fold cross-validation. Therefore, our results do not confirm the study of Berghof et al. [15] that concluded that these two methods yielded the same trait when analyzing body weight variability in layer hens. In addition, the GWAS results of our study reveal that these two traits are controlled by different genomic regions, given that only the region on SSC7 was significant for both traits. This is in line with the presence of some reranking of EBV when comparing LnVar and DHGLM, which after deregression were used as response variable in GWAS. Thus, our results indicate that LnVar and DHGLM yield, to a large extent, genetically different phenotypes of variability. Moreover, we also showed in the three-fold cross-validation that DHGLM provides more accurate EBV. This means that the two methods should not be treated as interchangeable and although DHGLM has a longer computation time and is more difficult to implement in a real-life breeding program, we recommend it over the simpler methods. This is in line with the findings of Sell-Kubiak et al. [14] and Iung et al. [19].

Significant SNPs and candidate genes

Within each vQTL region for variability of litter size, several candidate genes were identified. We focused only on genes that are located within ± 50 kb from the most significant SNP in each vQTL region. The most significant SNP (AX-116689108) for both variability phenotypes was located on SSC7 within a non-coding region but notably in the middle of a regulatory element (genomic evolutionary rate profiling, GERP) [39]. In our study of 2015 on variability of litter size, which included a much smaller number of animals from the same population (N = 2067), we also identified a SNP on SSC7 that was significantly associated with varTNB_2015 [25]. This SNP was located at 43.76 Mb based on the Sus scrofa build 10.2 [25] but at 38.26 Mb in the Sus scrofa build 11.1 used in the current study. However, in the current study, this SNP was not significant [− log10(P-value) = 4.05]. The LD between this SNP and the most significant SNP from the current study (at 41.8 Mb on SSC7) was only 0.11. Although this is not a strong LD, it indicates that this region on SSC7 plays an important role in litter size variability.

The two genes that are located within ± 50 kb from the most significant SNP on SSC7 for both traits are ADGRF1—adhesion G protein-coupled receptor F1 (SSC7:41,806,393–41,853,657 bp) and ADGRF5—adhesion G protein-coupled receptor F5 (SSC7:41,640,258–41,769,286 bp). The ADGRF1 GO term annotation relates it to transmembrane signaling receptor activity, for which ADGRF5 is an important paralog [27]. ADGRF1 is involved in neurodevelopment of the brain and its functions are related to the effect of docosahexaenoic acid on the brain [42, 43]. ADGRF5 was recently reported to be involved in the prevention of paraquat-related lung injuries and to be important for the function of the respiratory system [44] and in the process of vascularization [45, 46]. Moreover, knockout mice that lack ADGRF5 (in combination with a knockout of another gene adhesion G protein-coupled receptor ADGRL4) show perinatal lethality in 50% of the animals [46]. These functions can have an important effect on the blood supply to developing fetuses. Both ADGRF1 and ADGRF5 are expressed in human ovary, uterus, prostate, and testis tissues [27].

Another identified vQTL region for varTNB was also located on SSC7, with the most significant SNP being AX-116320493 and the candidate gene being AP3B2—adaptor related protein complex 3 subunit beta 2, which is expressed in the testis and prostate [27]. Mutations of this gene have been reported to result in neurologic disorders in humans [47].

The two other candidate genes for LnVarTNB were GANC—glucosidase alpha, neutral C for the identified vQTL on SSC1 and AHCYL2 adenosylhomocysteinase like 2 on SSC18. In humans, GANC is expressed in several organs related to reproduction in females (breast, uterus, cervix, and ovary) and in males (testis, prostate, and seminal vesicle) [27]. GANC encodes a member of the glycosyl family, which is a key enzyme in the metabolism of glycogen and is associated with susceptibility to diabetes [48, 49]. AHCYL2 is involved in the development of congenital heart defects in humans, and a GWAS in Chinese cattle also described it as a candidate gene associated with displacement of the abomasum [50]. It is also expressed in the ovary and uterus and in the testis and prostate [27].

The last of the most significant SNPs for varTNB was AX-116416839 located on SSC11 within the candidate gene KATNAL1 katanin catalytic subunit A1 like 1. This gene is associated mostly with an expression in neurons [51], but it has been shown to have a role in the regulation of the Sertoli cell microtubules, which if disturbed can cause male infertility [52]. Since the functions of the candidate genes are not directly linked with female reproduction, it would be useful to further study the existence of causative mutations underlying variability of litter size.

Conclusions

We identified six novel genomic regions that are associated with the variability of litter size in pigs. Only one vQTL region, on SSC7, partially overlapped between the variability traits obtained with the two methods (LnVar and DHGLM) used here and, in both cases, it contained the same most significant SNP. Both our current findings and those of a previous study of the same population, provide strong evidence for a causative mutation on SCC7 for litter size variability. However, future studies based on sequence data are needed to confirm the genomic regions involved in the control of variability of litter size, since the most significant SNP on SSC7 was detected within a non-coding region. In addition, our results indicate that the LnVar and DHGLM methods that were used to estimate the variability of litter size produced phenotypically and genetically different traits, and that DHGLM yields much more accurate results. Thus, we recommend the use of DHGLM over the simpler method to study and implement selection on the variability of litter size in breeding programs.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets generated and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available because they are part of the commercial breeding program of Topigs Norsvin. They are however available upon reasonable request (contact: egbert.knol@topigsnorsvin.com).

References

Bruijning M, Metcalf CJE, Jongejans E, Ayroles JF. The evolution of variance control. Trends Ecol Evol. 2020;35:22–33.

Shen X, Pettersson M, Rönnegård L, Carlborg Ö. Inheritance beyond plain heritability: variance-controlling genes in Arabidopsis thaliana. PLoS Genet. 2012;8:e1002839.

Queitsch C, Sangster TA, Lindquist S. Hsp90 as a capacitor of phenotypic variation. Nature. 2002;417:618–24.

Rutherford S, Hirate Y, Swalla BJ. The Hsp90 capacitor, developmental remodeling, and evolution: the robustness of gene networks and the curious evolvability of metamorphosis. Crit Rev Biochem Mol. 2007;42:355–72.

Sangster TA, Bahrami A, Wilczek A, Watanabe E, Schellenberg K, McLellan C, et al. Phenotypic diversity and altered environmental plasticity in Arabidopsis thaliana with reduced Hsp90 levels. PLoS One. 2007;2:e648.

Hill WG, Mulder HA. Genetic analysis of environmental variation. Genet Res (Camb). 2010;92:381–95.

Ibáñez-Escriche N, Varona L, Sorensen D, Noguera JL. A study of heterogeneity of environmental variance for slaughter weight in pigs. Animal. 2008;2:19–26.

Ros M, Sorensen D, Waagepetersen R, Dupont-Nivet M, SanCristobal M, Bonnet JC, et al. Evidence for genetic control of adult weight plasticity in the snail Helix aspersa. Genetics. 2004;168:2089–97.

Sonesson AK, Ødegård J, Rönnegård L. Genetic heterogeneity of within-family variance of body weight in Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar). Genet Sel Evol. 2013;45:41.

Sae-Lim P, Khaw HL, Nielsen HM, Puvanendran V, Hansen Ø, Mortensen A. Genetic variance for uniformity of body weight in lumpfish (Cyclopterus lumpus) used a double hierarchical generalized linear model. Aquaculture. 2020;514:734515.

Mulder HA, Gienapp P, Visser ME. Genetic variation in variability: Phenotypic variability of fledging weight and its evolution in a songbird population. Evolution. 2016;70:2004–16.

Yousefi Zonuz A, Alijani S, Rafat SA. Genetic heterogeneity of residual variance of hatch weight in Mazandaran native chicken. Br Poult Sci. 2019;60:366–72.

Sell-Kubiak E, Wang S, Knol EF, Mulder HA. Genetic analysis of within-litter variation in piglets’ birth weight using genomic or pedigree relationship matrices. J Anim Sci. 2015;93:1471–80.

Sell-Kubiak E, Bijma P, Knol EF, Mulder HA. Comparison of methods to study uniformity of traits: application to birth weight in pigs. J Anim Sci. 2015;93:900–11.

Berghof TVL, Bovenhuis H, Mulder HA. Body weight deviations as indicator for resilience in layer chickens. Front Genet. 2019;10:1216.

Yang J, Loos RJF, Powell JE, Medland SE, Speliotes EK, Chasman DI, et al. FTO genotype is associated with phenotypic variability of body mass index. Nature. 2012;490:267–72.

Tropf FC, Lee SH, Verweij RM, Stulp G, van der Most PJ, De Vlaming R, et al. Hidden heritability due to heterogeneity across seven populations. Nat Hum Behav. 2017;1:757–65.

Rönnegård L, Felleki M, Fikse F, Mulder HA, Strandberg E. Genetic heterogeneity of residual variance-estimation of variance components using double hierarchical generalized linear models. Genet Sel Evol. 2010;42:8.

Iung LHS, Neves HHR, Mulder HA, Carvalheiro R. Genetic control of residual variance of yearling weight in Nellore beef cattle. J Anim Sci. 2017;95:1425–33.

Rönnegård L, Valdar W. Detecting major genetic loci controlling phenotypic variability in experimental crosses. Genetics. 2011;188:435–47.

Rönnegård L, Valdar W. Recent developments in statistical methods for detecting genetic loci affecting phenotypic variability. BMC Genet. 2012;13:63.

Nelson RM, Pettersson ME, Li X, Carlborg Ö. Variance heterogeneity in Saccharomyces cerevisiae expression data: trans-regulation and epistasis. PLoS One. 2013;8:e79507.

Geiler-Samerotte K, Bauer C, Li S, Ziv N, Gresham D, Siegal M. The details in the distributions: why and how to study phenotypic variability. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2013;24:752–9.

SEGES. Annual Report—Results. Copenhagen. 2020. https://pigresearchcentre.dk/About-us/Annual-reports. Accessed 30 Jun 2021.

Sell-Kubiak E, Duijvesteijn N, Lopes MS, Janss LLG, Knol EF, Bijma P, et al. Genome-wide association study reveals novel loci for litter size and its variability in a Large White pig population. BMC Genomics. 2015;16:1049.

Animal Genome Project. Pig QTL data base. http://www.animalgenome.org/QTLdb/pig.html. Accessed 30 Jun 2021.

Stelzer G, Rosen R, Plaschkes I, Zimmerman S, Twik M, Fishilevich S, et al. The GeneCards Suite: from gene data mining to disease genome sequence analysis. Curr Protoc Bioinformatics. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpbi.5.

Dobrzański J, Mulder HA, Knol EF, Szwaczkowski T, Sell-Kubiak E. Estimation of litter size variability phenotypes in Large White sows. J Anim Breed Genet. 2020;137:559–70.

Gilmour AR, Gogel BJ, Cullis BR, Thompson R. ASReml user guide release 3.0. Hemel Hempstead: VSN Int Ltd. 2009. https://www.vsni.co.uk/. Accessed 30 June 2021.

SanCristobal-Gaudy M, Elsen J-M, Bodin L, Chevalet C. Prediction of the response to a selection for canalisation of a continuous trait in animal breeding. Genet Sel Evol. 1998;30:423–51.

SanCristobal-Gaudy M, Bodin L, Elsen JM, Chevalet C. Genetic components of litter size variability in sheep. Genet Sel Evol. 2001;33:249–71.

Sorensen D, Waagepetersen R. Normal linear models with genetically structured residual variance heterogeneity: A case study. Genet Res. 2003;82:207–22.

Felleki M, Lee D, Lee Y, Gilmour AR, Rönnegård L. Estimation of breeding values for mean and dispersion, their variance and correlation using double hierarchical generalized linear models. Genet Res. 2012;94:307–17.

Garrick DJ, Taylor JF, Fernando RL. Deregressing estimated breeding values and weighting information for genomic regression analyses. Genet Sel Evol. 2009;41:55.

Sargolzaei M, Chesnais JP, Schenkel FS. A new approach for efficient genotype imputation using information from relatives. BMC Genomics. 2014;15:478.

Yang J, Lee SH, Goddard ME, Visscher PM. GCTA: A tool for genome-wide complex trait analysis. Am J Hum Genet. 2011;88:76–82.

Yang J, Zaitlen NA, Goddard ME, Visscher PM, Price AL. Advantages and pitfalls in the application of mixed-model association methods. Nat Genet. 2014;46:100–6.

Purcell S, Neale B, Todd-Brown K, Thomas L, Ferreira MAR, Bender D, et al. PLINK: A tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81:559–75.

Ensembl. Sscrofa 11.1. http://www.ensembl.org. Accessed 30 Jun 2021.

Sell-Kubiak E, Knol EF, Mulder HA. Selecting for changes in average “parity curve” pattern of litter size in Large White pigs. J Anim Breed Genet. 2019;136:134–48.

Berghof TVL, Poppe M, Mulder HA. Opportunities to improve resilience in animal breeding programs. Front Genet. 2019;9:692.

Kim HY, Spector AA. N-Docosahexaenoylethanolamine: A neurotrophic and neuroprotective metabolite of docosahexaenoic acid. Mol Aspects Med. 2018;64:34–44.

Lee JW, Huang BX, Kwon HS, Rashid MA, Kharebava G, Desai A, et al. Orphan GPR110 (ADGRF1) targeted by N-docosahexaenoylethanolamine in development of neurons and cognitive function. Nat Commun. 2016;7:13123.

Kubo F, Ariestanti DM, Oki S, Fukuzawa T, Demizu R, Sato T, et al. Loss of the adhesion G-protein coupled receptor ADGRF5 in mice induces airway inflammation and the expression of CCL2 in lung endothelial cells. Respir Res. 2019;20:11.

Niaudet C, Petkova M, Jung B, Lu S, Laviña B, Offermanns S, et al. Adgrf5 contributes to patterning of the endothelial deep layer in retina. Angiogenesis. 2019;22:491–505.

Lu S, Liu S, Wietelmann A, Kojonazarov B, Atzberger A, Tang C, et al. Developmental vascular remodeling defects and postnatal kidney failure in mice lacking Gpr116 (Adgrf5) and Eltd1 (Adgrl4). PLoS One. 2017;12:e0183166.

Assoum M, Philippe C, Isidor B, Perrin L, Makrythanasis P, Sondheimer N, et al. Autosomal-recessive mutations in AP3B2, adaptor-related protein complex 3 beta 2 subunit, cause an early-onset epileptic encephalopathy with optic atrophy. Am J Hum Genet. 2016;99:1368–76.

Hirschhorn R, Huie ML, Kasper JS. Computer assisted cloning of human neutral α-glucosidase C (GANC): a new paralog in the glycosyl hydrolase gene family 31. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:13642–6.

Dewey S, Lai X, Witzmann FA, Sohal M, Gomes AV. Proteomic analysis of hearts from Akita mice suggests that increases in soluble epoxide hydrolase and antioxidative programming are key changes in early stages of diabetic cardiomyopathy. J Proteome Res. 2013;12:3920–33.

Huang H, Cao J, Guo G, Li X, Wang Y, Yu Y, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies QTLs for displacement of abomasum in Chinese Holstein cattle. J Anim Sci. 2019;97:1133–42.

Hatakeyama E, Hayashi K. KATNAL1 is a more active and stable isoform of katanin, and is expressed dominantly in neurons. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2018;507:389–94.

Smith LB, Milne L, Nelson N, Eddie S, Brown P, Atanassova N, et al. KATNAL1 regulation of sertoli cell microtubule dynamics is essential for spermiogenesis and male fertility. PLoS Genet. 2012;8:e1002697.

Mackay TFC, Lyman RF. Drosophila bristles and the nature of quantitative genetic variation. Philos T R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2005;360:1513–27.

Ordas B, Malvar RA, Hill WG. Genetic variation and quantitative trait loci associated with developmental stability and the environmental correlation between traits in maize. Genet Res (Camb). 2008;90:385–95.

Paré G, Cook NR, Ridker PM, Chasman DI. On the use of variance per genotype as a tool to identify quantitative trait interaction effects: a report from the Women’s Genome Health Study. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:e1000981.

Ayroles JF, Buchanan SM, O’Leary C, Skutt-Kakaria K, Grenier JK, Clark AG, et al. Behavioral idiosyncrasy reveals genetic control of phenotypic variability. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112:6706–11.

Perry GML, Nehrke KW, Bushinsky DA, Reid R, Lewandowski KL, Hueber P, et al. Sex modifies genetic effects on residual variance in urinary calcium excretion in rat (Rattus norvegicus). Genetics. 2012;191:1003–13.

Wolc A, Arango J, Settar P, Fulton JE, O’Sullivan NP, Preisinger R, et al. Genome-wide association analysis and genetic architecture of egg weight and egg uniformity in layer chickens. Anim Genet. 2012;43:87–96.

Jimenez-Gomez JM, Corwin JA, Joseph B, Maloof JN, Kliebenstein DJ. Genomic analysis of QTLs and genes altering natural variation in stochastic noise. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:e1002295.

Mulder HA, Crump R, Calus MPL, Veerkamp R. Unraveling the genetic architecture of environmental variance of somatic cell score using high-density single nucleotide polymorphism and cow data from experimental farms. J Dairy Sci. 2013;96:7306–17.

Ek WE, Rask-Andersen M, Karlsson T, Enroth S, Gyllensten U, Johansson Å. Genetic variants influencing phenotypic variance heterogeneity. Hum Mol Genet. 2018;27:799–810.

Wang X, Liu X, Deng D, Yu M, Li X. Genetic determinants of pig birth weight variability. BMC Genet. 2016;17:41.

Wang Y, Ding X, Tan Z, Ning C, Xing K, Yang T, et al. Genome-wide association study of piglet uniformity and farrowing interval. Front Genet. 2017;8:194.

Iung LHS, Mulder HA, Neves HHR, Carvalheiro R. Genomic regions underlying uniformity of yearling weight in Nellore cattle evaluated under different response variables. BMC Genomics. 2018;19:619.

Hussain W, Campbell M, Jarquin D, Walia H, Morota G. Variance heterogeneity genome-wide mapping for cadmium in bread wheat reveals novel genomic loci and epistatic interactions. Plant Genome. 2020;13:e20011.

Wang X, Liu X, Deng D, Yu M, Li X. Genetic determinants of pig birth weight variability. BMC Genet. 2016;17:15.

Onteru SK, Fan B, Du ZQ, Garrick DJ, Stalder KJ, Rothschild MF. A whole-genome association study for pig reproductive traits. Anim Genet. 2011;43:18–26.

Tart JK, Johnson RK, Bundy JW, Ferdinand NN, McKnite AM, Wood JR, et al. Genome-wide prediction of age at puberty and reproductive longevity in sows. Anim Genet. 2013;44:387–97.

Coster A, Madsen O, Heuven HCM, Dibbits B, Groenen MAM, van Arendonk JAM, et al. The imprinted gene DIO3 is a candidate gene for litter size in pigs. PLoS One. 2012;7:e31825.

Jiao S, Maltecca C, Gray KA, Cassady JP. Feed intake, average daily gain, feed efficiency, and real-time ultrasound traits in Duroc pigs: II. genomewide association. J Anim Sci. 2014;92:2846–60.

Duijvesteijn N, Veltmaat JM, Knol EF, Harlizius B. High-resolution association mapping of number of teats in pigs reveals regions controlling vertebral development. BMC Genomics. 2014;15:542.

Zhuang Z, Ding R, Peng L, Wu J, Ye Y, Zhou S, et al. Genome-wide association analyses identify known and novel loci for teat number in Duroc pigs using single-locus and multi-locus models. BMC Genomics. 2020;21:344.

Rosendo A, Iannuccelli N, Gilbert H, Riquet J, Billon Y, Amigues Y, et al. Microsatellite mapping of quantitative trait loci affecting female reproductive tract characteristics in Meishan × Large White F2 pigs. J Anim Sci. 2012;90:37–44.

Petrovski S, Wang QL. Permutation based QQ plot and inflation factor estimation. Version 1.0.1. 2016. https://github.com/cran/QQperm/blob/master/DESCRIPTION/. Accessed 15 Dec 2021.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Barbara Harlizius, Arne Gjuvsland and Esinam Nancy Amuzu-Aweh for their valuable comments during the development of this study.

Funding

This project was financed by the National Science Centre, Poland (NCN SONATA Grant No. 2016/23/D/NZ9/00029; ESK is the grant holder) whereas publication of the manuscript was possible by the statutory funding of the Department of Genetics and Animal Breeding at Poznan University of Life Sciences (grant no. 506.534.04.00). ESK also acknowledges the financial support of the Polish Ministry of Science and Higher Education (Grant No. 1021/STYP/12/2017).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

ESK initiated and designed the study, prepared the phenotypic data, performed the analysis on phenotypes and post-GWAS evaluation as well as wrote the paper. ML prepared the genotypic data, performed the GWAS, and contributed to the writing of the manuscript. EFK was a discussion partner and contributed to the writing of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Figure S1.

Expected and observed − log10 P-values of SNPs associated with litter size variability defined as LnVarTNB and varTNB with inflation factor (lambda) that were estimated using the R package QQperm [74]. Figure S2. Manhattan plot of the genome-wide association study for total number born in the Large White pig population.

Additional file 2: Table S1.

SNPs significantly associated with the total number born with chromosome number (SSC) and minor allele frequency (MAF).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Sell-Kubiak, E., Knol, E.F. & Lopes, M. Evaluation of the phenotypic and genomic background of variability based on litter size of Large White pigs. Genet Sel Evol 54, 1 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12711-021-00692-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12711-021-00692-5