Abstract

Early diagnosis, monitoring and treatment selection of cancer represent major challenges in medicine. The definition of the complex clinical and molecular landscape of cancer requires the combination of multiple techniques and the investigation of multiple targets. As a result, diagnosis is normally lengthy, expensive and, in many cases, cannot be performed recursively. In recent years, optical biosensors, especially those based on the unique properties of plasmonic nanostructures, have emerged as one of the most exciting tools in nanomedicine, capable of overcoming key limitations of classical techniques. In this review, we specifically focus our attention on the latest advances in optical biosensors exploiting surface-enhanced Raman scattering encoded particles for the characterization of tumor single cells (molecular biology) and tissues (immunohistochemistry and guided surgery), as well as their application in guided surgery or even in bioimaging of living organisms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Nowadays, one of the fundamental goals in medicine is the characterization of cancer for early diagnosis, monitoring and treatment selection (precision medicine). To this end, techniques such as cytology (Schramm et al. 2011), immunohistochemistry (Gown 2008), genomics [i.e., fluorescent in situ hybridization, FISH (Gerami et al. 2009), polymerase chain reaction, PCR (Khan and Sadroddiny 2016)] and next-generation sequencing (Koboldt et al. 2013) are currently employed to investigate solid samples of tumor obtained by biopsy or surgery. Alternatively, imaging tools such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (Verma et al. 2012), computerized tomography scan (CTS) (Pearce et al. 2012), positron emission tomography (PET) (Silvestri et al. 2013) and the different variants of ultrasound imaging such as endobronchial ultrasound imaging and echoendoscopy (Gu et al. 2009; Kuhl et al. 2005) are commonly applied directly on the patient. As cancer is a multifactorial disease; a combination of information using different technologies, various imaging agents and diverse biomarkers is required to avoid ambiguity. Thus, diagnosis is normally lengthy, expensive and, in many cases, cannot be performed recursively, as it would require monitoring the actual state of the disease and the efficiency of the treatment. In the last decade, many approaches have been developed to complement or even substitute the current methodologies in cancer diagnosis and monitoring. In fact, there is a strong interest in the development of highly sensitive nanotechnological methodologies that would shift medical diagnosis (Howes et al. 2014) to the next level of the state of the art in biomedical diagnostics (Pelaz et al. 2017), pathogen detection (Pazos-Perez et al. 2016) or gene identification (Morla-Folch 2016; Morla-Folch et al. 2017). Among them, optical systems are ideally suited for fast and accurate classification of tumor cells and tissues, early detection of intraepithelial or intraductal diseases, including most cancers, and to assess tumor margins and response to therapy. Optical methods offer several significant advantages over the routine clinical imaging methods, including noninvasiveness through the use of safe nonionizing radiation, the transparency of the soft tissues to the radiation in the biological window (Qian et al. 2008; Smith et al. 2009), a facility for continuous bedside monitoring, and the high spatial resolution (< 0.5 μm lateral resolution in the visible range) (Álvarez-Puebla 2012).

Optical nanosensors based on surface-enhanced Raman scattering (SERS) are currently emerging as one of the most powerful tools in biomedicine. SERS combines the extremely rich structural specificity and experimental flexibility of Raman spectroscopy with the tremendous sensitivity provided by the plasmonic nanostructure-mediated amplification of the optical signal (Le and Etchegoin 2009; Schlücker 2014). SERS spectroscopy has now reached a level of sophistication that makes it competitive with classical methods (e.g., confocal fluorescence microscopy) as it provides direct biochemical information (vibrational fingerprint). The structural fingerprinting is very effective owing to its narrow and highly resolved bands (0.1 nm compared with a bandwidth of 20–80 nm for fluorescence). This resolution, in addition, can be exploited for the generation of a potentially infinite number of SERS-encoded particles (SEPs) that can be used as contrast agents for real multiplex analysis. During the last 10 years, SERS has been extensively used for the study and characterization of single tumor cells, tumor tissues or even in vivo imaging of tumors (Jenkins et al. 2016). Although some strategies based on direct SERS (using “bare” plasmonic nanoparticles with no surface functionalization) (Allain and Vo-Dinh 2002; Baena and Lendl 2004; González-Solís et al. 2013; Sha et al. 2007) or even normal Raman scattering (Kong et al. 2015) have been proposed, nowadays the most promising alternatives rely on the use of SERS-encoded particles to screen, detect and characterize tumor cells and tissues.

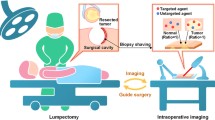

Here, we review the latest advances exploiting SERS-encoded particles for the characterization of tumor single cells (molecular biology) and tissues (immunohistochemistry and guided surgery), as well as their application in bioimaging of living organisms (diagnosis), as illustratively summarized in Fig. 1).

Adapted with permission from Gao et al. (2015). Copyright 2015, Elsevier

Schematic outline of a representative example of SERS-encoded particle (SEP) and illustrative images of diverse classes of applications for SEPs in (i) SERS imaging of an individual MCF-7 cell; adapted with permission from Nima et al. (2014). Copyright 2014, Nature Publishing Group. (ii) Ex vivo SERS imaging of a tumor tissue; adapted with permission from Wang et al. (2016). Copyright 2016, Nature Publishing Group. (iii) In vivo SERS imaging at two different sites of an injected tumor.

Surface-enhanced Raman scattering encoded particles

The ability to quantify multiple biological receptors in parallel using a single sample allows researchers and clinicians to obtain a massive volume of information with minimal assay time, sample quantity and cost. Classically, such multiplexed analysis has been carried out by using fluorescent labels (e.g., by attaching fluorophores to antibodies in the case of immunostaining). Unfortunately, the broad (20–80 nm) and unstructured signal provided by fluorescence limits to no more than four the number of codes that can be used simultaneously and unambiguously in the same sample. In contrast, the high spectral resolution of SERS allows acquiring well-defined vibrational spectra with bandwidths smaller than 0.1 nm. Since each vibrational SERS spectra represents the chemical fingerprint of a specific molecule, the combination of efficient plasmonic nanoparticles with molecular systems of large Raman cross sections (SERS probes) can generate a potentially infinite library of encoded nanoparticles. Thus, SERS-encoded particles (SEPs) can be schematized as hybrid structures comprising a plasmonic nanoparticle core, usually of silver or gold, coated with a SERS code and, preferably, with an additional protective layer of polymer or inorganic oxide (mainly silica). It is worth noting that the terms SERS “code”, “probe”, “label”, “reporter”, and “active molecule” are generally used as synonyms in the scientific literature. Besides the multiplexing capabilities, SEPs may also offer key advantages such as (i) quantitative information, as the spectral intensity of the corresponding SERS code can be devised to scale linearly with the concentration of particles; (ii) the need for only a single laser excitation wavelength to excite the Raman spectra of all SEPs; and (iii) a high photostability and optimal contrast when near-infrared (NIR) excitations are employed to minimize the disturbing autofluorescence of cells and tissues, while protecting them from the damage caused by visible lasers (Wang and Schlucker 2013).

Once prepared, SEPs can be conjugated with a variety of molecular species to afford selectivity. For example, SEPs have been coupled with antibodies, nucleic acids sequences or folates and used for selective targeting and imaging of different substrates such as cells and tissues (Fabris 2016). It is worth noting that, in addition to such active targeting, SEPs can also be delivered to tumors by a passive targeting mechanism (Maeda et al. 2013; Weissleder et al. 2014). This approach exploits the preferred accumulation of nanoparticles, within a certain size range and surface charge, on cancer tissue as compared to normal tissues, a unique biological mechanism ascribed to an enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect such as micropinocytosis.

The major challenges associated with the SEP production are related to: (i) the colloidal stability; (ii) functionalization and immobilization of (bio)molecules at the particle surface; and (iii) leaching of the SERS probe. Several alternatives have been reported to overcome these problems. Figure 2a illustrates a typical procedure to fabricate the SEPs either with or without encapsulation. The simplest way to produce SEPs is by using citrate-stabilized spherical Au or Ag colloids functionalized with a mixed layer of an SERS active molecule and a stabilizing agent such as thiolated polyethylene glycol (PEG), mercaptoundecanoic acid (MUA) or bovine serum albumin (BSA) (Fig. 2b). The outer protective layer improves nanoparticle stability and prevents the desorption of the SERS codes from the particle surface. Further, the external stabilizing coating provides functional groups on their surface for further bioconjugation (e.g., antibodies or aptamers) for selective targeting (Catala et al. 2016; Conde et al. 2014; Pallaoro et al. 2011).

Reproduced with permission from Wang et al. (2012). Copyright 2012, Wiley-VCH

a Schematic representation of a typical SEP fabrication route. b–j TEM images of various SEPs: b individual and c dimer Ag-encoded particles. Reproduced with permission from Catala et al. (2016) and Vilar-Vidal et al. (2016). Copyright 2016, Wiley-VCH, and 2016 Royal Society of Chemistry. d Ag nanostars functionalized with a Raman active molecule. Reproduced with permission from Rodríguez-Lorenzo et al. (2012). Copyright 2012, Springer-Nature. e Au nanorods coated with Ag and codified (reproduced with permission from Chen et al. (2016). f, g Spherical SERS-encoded Au particles coated with silica and NIPAM, respectively. Reproduced with permission from Álvarez-Puebla et al. (2009) and Mir-Simon et al. (2015). Copyright 2009, Wiley-VCH, and 2015, American Chemical Society. h Au nanostars functionalized with a Raman reporter and coated with silica. Reproduced with permission from Gao et al. (2015). Copyright 2016, Wiley-VCH, and 2016, Royal Society of Chemistry. i SERS-encoded Au@Ag nanorods deposited on silica-coated magnetic beads. These composite materials are further coated with an outer silica shell decorated with CdTe quantum dots. Reproduced with permission from Wang et al. (2014b). Copyright 2014, Wiley-VCH. j SERS-encoded silver particles coated, first, with silica and then with mesoporous TiO2 loaded with a fluorescent dye.

However, even though PEG or BSA improves SEP stability, nanoparticles are still susceptible to aggregation, and great care must be taken when manipulating colloids within biological fluids. Therefore, a more robust coating was also developed and applied on such constructs, such as a silica layer (Bohndiek et al. 2013; Jokerst et al. 2011; Mir-Simon et al. 2015) or polymers like poly(N-isopropyl acrylamide) (NIPAM) (Álvarez-Puebla et al. 2009; Bodelon et al. 2015) (Fig. 2f, g, respectively). These types of SEPs are very stable due to the protective glass or polymer shell on their surface which, furthermore, can be also easily modified to anchor biomolecules such as antibodies or aptamers. Thus, for this reason, nowadays, silica- and polymer-coated SERS-encoded nanoparticles are the most widely used SEPs.

SEPs made of metallic spherical cores are efficient enough for imaging, but larger amounts are required to yield good signals. To increase the SERS efficiency of SEPs, similar constructs were produced by using aggregates instead of individual nanoparticles. These structures are also usually encapsulated in silica, PEG or mixed BSA–glutaraldehyde for stability and protection of the SERS codes (Henry et al. 2016). This approach creates a collection of hot spots within the SEPs, leading to a considerable intensity increase. However, the limited control over aggregate geometric features (size, configuration and gap separation) that can usually be imposed in most of the nanofabrication methods determines significant intensity variability from SEP to SEP. Moreover, the final cluster sizes are relatively large. This factor is very important, as there is an intrinsic size limitation of around 300 nm after which the hydrodynamic stability of the particles is lost (Barbé et al. 2004; Feliu et al. 2017). On the contrary, when homogeneous assemblies such as dimers (Fig. 2c), trimers or even assemblies with higher coordination numbers can be prepared in high yields (Pazos-Perez et al. 2012; Romo-Herrera et al. 2011; Vilar-Vidal et al. 2016), the size limitations pose no longer a problem while extraordinary field enhancements for SERS are indeed generated. However, their current synthetic protocols are tedious and require multiple purification steps.

Different single particle morphologies such as stars or rods have been proposed to achieve higher SERS intensities than those produced by spherical particles without using complicated assembly processes or producing inhomogeneous aggregates. Nanostars and nanorods accumulate the electromagnetic field at their tips, giving rise to very strong single particle SERS intensities (Alvarez-Puebla et al. 2010). Similar approaches as for spherical colloids were applied for the preparation of SEPs using Au nanostars functionalized with thiolated PEG (Morla-Folch et al. 2014; Yuan et al. 2012), or coated with silica shells (Andreou et al. 2016; Henry et al. 2016; Huang et al. 2016; Mir-Simon et al. 2015; Oseledchyk et al. 2017). Figure 2d, h shows Au nanostars coated with Ag and silica, respectively. The obtained intensities of the SEPs produced with Au nanostars are consistently higher than those of spherical particles of the same size (Mir-Simon et al. 2015). However, although many nanostars look homogeneous, the actual geometrical parameters of their tips are not (Rodríguez-Lorenzo et al. 2009), yielding significant intensity variability from particle to particle. Besides, nanostars are usually produced with polyvinylpyrrolidone (PVP) in dimethylformamide (DMF), thus demanding an extensive cleaning of the particles before the encoding process (PVP is retained at the gold surface after the synthesis, hampering the diffusion and adsorption of the SERS probes at the particle). Contrary to nanostars, geometrical features (length, width and even tip) of Au nanorods can be nowadays perfectly controlled (Chen et al. 2013) allowing for a homogeneous SERS response of each particle while also offering the possibility of fine-tuning their localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) within the visible–near infrared (Vis–NIR). This characteristic has been used in conjunction with well-selected dyes, to create SEPs with double resonance with the laser (i.e., LSPR of the particle + HOMO–LUMO band of the dye) giving rise to surface-enhanced resonance Raman scattering (SERRS) with the subsequent increase in the signal intensity up to two to three orders of magnitude (Jokerst et al. 2012a; Qian et al. 2011; Von Maltzahn et al. 2009). As silver exhibits larger plasmonic efficiency than gold, fabrication of Ag nanorods has been pursued to improve the enhancing SERS capabilities. However, the preparation of Ag nanorods is extremely challenging and, for this reason, silver coating of preformed Au nanorods (Au@Ag nanorods) has been largely preferred for this aim, paving the way to the fabrication of SEPs (Fig. 2e) with a considerable increase in the SERS intensity (Chen et al. 2016). Still, synthesis of nanorods requires the use of hexadecyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB) as a surfactant that electrostatically binds the metallic surface. As for PVP for nanostars, the CTAB layer hinders the adsorption of SERS probes at the nanoparticles, therefore demanding tedious and delicate post-synthetic procedures to efficiently produce SEPs. Notably, while SERS intensities provided by nanostars or nanorods are much higher than those of isolated rounded particles, they still remain far below those afforded by (controlled or random) aggregates of spherical nanoparticles.

Multimodal imaging technologies have also been developed by implementing SERS with other imaging techniques based on different physical effects such as fluorescence and magnetism. For instance, silica- or titania-coated SEPs (Fig. 2j) have been conjugated with fluorophores or quantum dots on the silica surface (Cui et al. 2011; Qian et al. 2011; Wang et al. 2012, 2014b). In this case, the final goal is combining the fast acquisition of fluorescence signal with the high multiplexing capability of SEPs. Likewise, since magnetic resonance (MR) imaging is also a technique widely used, bimodal SEPs combining SERS and magnetism have been similarly developed. Most of the reported structures are achieved by conjugating magnetic particles onto the outer silica shell of SEPs (Gao et al. 2015; Ju et al. 2015; Kircher et al. 2012). Finally, trimodal SEPs (Fig. 2i) have been also demonstrated by using a multi-layered structure where the inner core is a magnetic nanobead protected with a silica layer, which is further covered with SEPs (Au@Ag nanorods) and, finally, with an outer silica layer. This latter shell allows to fixate the deposited nanorods and provide anchor spots for CdTe quantum dots, which are exploited as the fluorescent agents (Wang et al. 2014b) These multimodal approaches further highlight the capabilities and great potential of SEPs for enabling more accurate imaging.

SEP characterization of single cells

Cancer cells, even those within the same tumor, are characterized by high phenotypic and functional heterogeneity as a result of the genetic or epigenetic change, environmental differences and reversible changes in cell properties (Meacham and Morrison 2013). Such intrinsic variability plays a major role in metastasis, therapy resistance and disease progression and, thus, experimental approaches capable of providing a complete molecular landscape of cancer are key tools in cancer diagnosis, prognosis and treatment (Meacham and Morrison 2013; Siravegna et al. 2017).

Although SERS microspectroscopy has been extensively employed in the study of tumor tissues (this will be discussed extensively in the next section), the phenotypic characterization of single cells is still in its infancy (Altunbek et al. 2016; Chourpa et al. 2008; Hu et al. 2016; Kneipp 2017; Nolan et al. 2012; Taylor et al. 2016). The rationale of using SERS for single cell studies over other imaging techniques, such as those based on fluorescence read-outs, rests on its high multiplexing capabilities, sensitivity and robustness to investigate the distinct properties of cancer cells, in particular by exploiting antibody-conjugated SEPs targeting cell membrane receptors for immunophenotyping studies. Arguably, the most impacting single cell SERS phenotyping was reported by Nima et al. (2014), who fabricated four different sets of SEPs (Fig. 3a) comprising an Au@Ag nanorod as the plasmonic unit, a unique SERS label and an antibody (Ab) selectively targeting a specific breast cancer marker. In detail, the authors employed three anti-epithelial cell adhesion molecules (anti-EpCAM, anti-CD44, anti-cytokeratin18), and an anti-insulin-like growth factor antigen (anti-IGF-I receptor β). Notably, rod nanoparticles were designed to display an absorption maximum in the NIR range (a spectral region where the biological tissue absorbance is minimal). As a result, SEPs also act as excellent photothermal (PT) contrast agents (Jain et al. 2008; Polo et al. 2013), enabling the possibility to combine a rapid sample pre-screening using pulsed PT excitation with the high sensitivity of multiplex SERS imaging. Molecular targeting of tumor cells was demonstrated in unprocessed healthy human blood (7 × 106 white blood cells, WBCs) spiked with MCF-7 cells (Nima et al. 2014). Upon 30 min incubation with the cocktail of SEPs, 2-D SERS mapping of a single MCF-7 cancer was acquired (Fig. 3b). Each of the four colors associated with the Raman vibrational barcode of the four SEPs can be easily distinguished despite the complex biological background, while no significant signals were collected from WBCs in the sample or from cancer cells in the absence of SEPs. Co-localization of multiple SEP signatures provides a highly enhanced level of detection specificity by rejecting false positive readings, which may arise from monoplex or biplex targeting. On the other hand, integration of super-contrast SERS method with PT functionality into bimodal SEPs dramatically reduces the imaging time, allowing the rapid detection of a single cancer cell without any tedious enrichment or separation steps.

Adapted with permission from Nima et al. (2014). Copyright 2014, Nature Publishing Group

a Outline of the fabrication steps of silver-coated gold nanorods (Au@Ag nanorods) and corresponding SERS spectra of four different SEPs. The following colors were assigned to a non-overlapping peak from each SERS spectrum: (i) blue (SERS label: 4MBA; Ab: anti-EpCAM); (ii) red (PNTP/anti-IGF-1 Receptor β); (iii) green (PATP/anti-CD44); (iv) magenta (4MSTP/anti-Cytokeratin18). 4MBA 4-mercaptobenzoic acid, PNTP p-nitrobenzoic acid, PATP p-aminobenzoic acid and 4MSTP 4-(methylsulfanyl) thiophenol. b Transmission and SERS imaging of: (i) MCF-7 cell incubated with SEPs; (ii) MCF-7 cell with no SEPs (control); (iii) normal fibroblast cell incubated with SEPs. The cells proceed from of a sample containing just one MCF-7 cell among 90,000 fibroblast cells.

Multimodal SEPs for fast and multiplexed imaging of cancer cells in vitro were also previously employed by Wang et al. (2012), who, in this case, integrated fluorescence and SERS signal read-outs. On the other hand, the multiplexing capabilities of SERS imaging with SEPs were further investigated by Bodelon et al. (2015), who discriminated human epithelial carcinoma A431 and nontumoral murine fibroblast 3T3 2.2 cells in mixed populations cultured in vitro. Here, three Ab-functionalized SEPs, comprising gold octahedra as plasmonic units, are simultaneously retained at the cancer cell membrane, while only one is found to display affinity toward membrane receptors on the healthy cells.

Notably, although the field of SERS single cell phenotyping is still limited, it is under rapid development due to the enormous potential in terms of: (i) identification of new therapeutical targets that may allow for the discovery of novel and more selective therapies to safely target and kill tumor cells; and (ii) classification and recognition of different tumor cells, which may lead to their easy detection allowing for pre-symptomatic diagnoses or relapses. In the latter case, direct identification of tumor markers, such as cancer cells, contained in bodily fluids (i.e., liquid biopsies) likely represents the most powerful approach for the noninvasive and real-time monitoring of the disease progression or recurrence and the response to various treatments, which can also lead to key insights into the development of specific resistances (Schumacher and Scheper 2016; Siravegna et al. 2017). In this regard, studies of integration of SEPs with modular microfluidic platforms have demonstrated the potential to efficiently combine in an assay the rapid sample processing and precise control of biofluids with the fast optical detection of cancer cells (Hoonejani et al. 2015; Pedrol et al. 2017; Sackmann et al. 2014; Shields et al. 2015; Zhou and Kim 2016).

SEP characterization of tumor tissues

The classical pathologic examination of tumors (morphohistological) is not capable of outlining all dimensions of the clinical disease. On the other hand, the molecular characterization of tumors, consistently applied in clinical oncology, identifies the disease, adds predictive and prognostic value, and determines the presence of specific therapeutic targets. This class of analyses is typically performed on solid tissues acquired through invasive biopsies. Posteriorly, the samples are analyzed in the pathology laboratory by histo/immunohistochemistry (HC/IHC). This allows to determine the morphological characteristics and the expression of biomarkers in the tissues reaching, thus, a diagnosis and prognosis (Subik et al. 2010). This process is expensive and slow as it requires the characterization of the patient samples by a panel of fluorescent immunolabeled markers (ranging from 5 to 10 as a function of the type of tumor) that should be applied separately in different cuts of the tissue sample. The general steps for each of these markers involves pre-analytic (fixation, embedding, processing and sectioning), analytic (permeation, staining and visualization) and post-analytic steps (interpretation and diagnosis). Thus, a multiplexing alternative is highly attractive for the pathologist. One of the oldest approaches to simulate HC/IHC with SEPs comprises the so-called composite organic–inorganic nanoparticles (COINs) (Lutz et al. 2008). COINs are fabricated via the controlled code-induced aggregation of silver particles with the subsequent coating with a silica shell. Notably, through the appropriate functionalization of the different coded COINs with antibodies [in this case, anti-cytokeratin-18 (BFU-CK18) and anti-PSA antibody (AOH-PSA)], the staining of formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded prostate tissue sections can be achieved, allowing for the localization of the tumor tissue (Fig. 4).

Adapted with permission from Lutz et al. (2008). Copyright 2008, American Chemical Association

a White light image of a formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded prostate tissue section stained with two COIN SEPs coded either with acridine orange (AOH) or basic fuchsin (BFU) and nucleic acid stain (YOYO). Each coin was functionalized with a different antibody anti-PSA (AOH-PSA) and anti-cytokeratin-18 (BFU-CK18). SERS mapping of b BFU-CK18 and c AOH-PSA. d Fluorescence mapping of YOYO. e Co-localization image that identifies epithelial nuclei (magenta) and co-expression of CK18 and PSA specifically in the epithelium (yellow).

In the last few years, this imaging technique has progressively evolved from the simple staining of the common samples used in pathology for HC/IHC to the direct application on tissues that can be stained without additional procedures. For example, Wang et al. (2016) have demonstrated the possibility of direct staining and imaging of mouse HER-2 positive breast tumor tissues by applying SEPs functionalized with anti-HER2, followed by a rapid rinse with serum to remove unspecifically deposited SEPs (Fig. 5).

Adapted with permission from Wang et al. (2016). Copyright 2016, Nature Publishing Group

a Absolute nanoparticle concentrations and b nanoparticle concentration ratios on normal tissues and tumors (10 tissue specimens from 5 patients). c Images of four tissue specimens from four patients: two HER2-positive specimens containing both tumor and normal tissue regions and two HER2-negative specimens (one tumor and one normal tissue). d Images of the concentration ratio of HER2-SEPs vs. isotype-SEPs and e IHC staining with an anti-HER2 monoclonal Ab. Unlabeled scale bars represent 2 mm.

This technique of using SEPs as contrast agents, together with the advances in miniaturization of the Raman systems (Kang et al. 2016; Wang et al. 2016), paves the way for the utilization of SEPs directly in the operating theater for intraoperative guidance of tumor resection (i.e., identification of residual tumors at the margins for their complete removal). Notably, two different strategies have been proposed: topical and systematic administration of SEPs. In the first one, SEPs are added directly to the tumor area when the patient is being operated (Fig. 6). In fact, it has been demonstrated that SEPs can adhere to tumor tissues in less than minutes, although the nonspecifically adsorbed SEPs must be removed by washing the tissue with serum (Wang et al. 2014a). The obstacle set by the high background distribution of non-specifically bound nanoparticles can be overcome by implementing ratiometric approaches where one of the SEP type in the particle cocktail is used as a nonspecific internal reference to visually enhance the preferential adhesion of other targeting nanoparticles on tumor tissues (Mallia et al. 2015; Oseledchyk et al. 2017; Pallaoro et al. 2011). Implementation of these methods is rather straightforward for SERS imaging due to the high degree of multiplexing provided by the narrow Raman linewidths. Further, the use of negative control SEPs also accounts for the nonhomogenous delivery of the nanoparticles as well as the variability of the working distances between the optical device and the sample (Garai et al. 2015).

Adapted with permission from Wang et al. (2014a). Copyright 2014, World Scientific Publishing

In vivo ratiometric analysis of multiplexed SEPs on tumor implants. a Mouse with surgically exposed tumors; the inset provides a magnified view of the 2.5-mm diameter flexible Raman probe. b Reference Raman spectra of pure SEPs (red: S420, gray: S421 and blue: S440) and tissue background with no SEP (black). c Raw spectra of SEPs applied on tissue acquired with a 0.1 s integration time (black), best fit curve using a DCLS algorithm (green), spectra of SEPs on tissue after tissue background removal using a DCLS algorithm (orange) and the DCLS-demultiplexed NP spectra (blue: EGFR-S440, red: HER2-S420, gray: isotype-S421). The concentration ratio of targeted and non-targeted nanoparticles topically applied on exposed tumors and normal tissues is plotted for (d–i) Image-grid experiment. d Mouse with two adjacent tumor xenografts. e Photograph of stained tissue. f Map of the absolute concentration (pM) of EGFR-SEP. SERS maps for g EGFR-SEP and, h HER2-SEP. i Overlay of EGFR and HER2 SEPs.

In addition to active tumor targeting accomplished by imparting to nanoparticles selectivity toward specific tumor antigens via conjugation with molecular elements such as antibodies and aptamers, SEPs can also be delivered to tumors by a passive targeting mechanism. This mechanism exploits the preferred accumulation of nanoparticles, within a certain size range and surface charge, on cancer tissue as compared to normal tissues, a unique biological mechanism ascribed to an enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) effect (Maeda et al. 2013). The EPR effect was also exploited in the application of SEPs to intraoperative targeted SERS imaging (here, SEPs are injected into the patient’s body before the operation) (Andreou et al. 2016; Oseledchyk et al. 2017). This approach has demonstrated extraordinary potential in enabling the complete resection of brain tumors (Fig. 7) (Gao et al. 2015; Huang et al. 2016; Jokerst et al. 2012b; Kircher et al. 2012). However, it is worth stressing that the in vivo biomolecular interactions of nanoparticles at extracellular, intracellular and cell surface levels are extremely complex and far from being well understood. This often poses major obstacles for the efficient targeted delivery of SEPs, which is further aggravated by the high diversity of the tumor microenvironments (MacParland et al. 2017; Polo et al. 2017). At the same time, such extensive nanoparticle–cell interactions are known to potentially cause multiple adverse physiological effects, including inflammation and immunological responses which can eventually results in tissue and organ dysfunctions (Kim et al. 2013; Lasagna-Reeves et al. 2010). Thus, a greater understanding of these nanoparticle interactions with biomolecules and cells in vivo, and their biological consequences, is of outmost importance in fully enabling the successful design of minimally invasive SEPs (Kim et al. 2013; Polo et al. 2017).

Adapted with permission from Kircher et al. (2012). Copyright 2012, Nature Publishing Group

SERS-guided intraoperative surgery using SEPs. a, b Living tumor-bearing mice (n = 3) underwent craniotomy under general anesthesia. Quarters of the tumor were then sequentially removed (as illustrated in the photographs, a), and intraoperative SERS imaging was performed after each resection step (b) until the entire tumor had been removed, as assessed by visual inspection. After the gross removal of the tumor, several small foci of SERS signal were found in the resection bed (outlined by the dashed white square; some SERS images are smaller than the image frame). The SERS color scale is shown in red from − 40 to 0 dB. c A subsequent histological analysis of sections from these foci showed an infiltrative pattern of the tumor in this location, forming finger-like protrusions extending into the surrounding brain tissue. As shown in the Raman microscopy image (right), an SERS signal was observed within these protrusions, indicating the selective presence of SEPs. The box is not drawn to scale. The SERS signal is shown in a linear red color scale.

In vivo imaging with SEPs

In 2008, Nie and coworkers (Qian et al. 2008) reported the first example of in vivo SERS imaging of a xenograft tumor model in mice. They employed SEPs comprising a spherical gold nanoparticle functionalized with a mixed layer of a resonant SERS label (malachite green) and thiolated PEG derivatives, and further conjugated with an antibody targeting EGFR-positive tumors. Once introduced into blood circulation via intravenous injection, the nanoparticles preferably concentrate at the tumor area during the subsequent 4–6 h where they largely remain for > 24–48 h (Fig. 8a). This allowed the spectroscopic detection of the tumor by SERS, as revealed by the acquisition of the intense vibrational fingerprint of malachite green (Fig. 8b). Lower but significant nonspecific particle uptakes by the liver and the spleen were also detected.

Adapted with permission from Qian et al. (2008). Copyright 2008, Nature Publishing Group

a ScFv EGFR-conjugated SEPs (plasmonic core: spherical gold nanoparticle; SERS label: malachite green) administered via intravenous tail injection to a nude mouse bearing human head-and-neck squamous cell carcinoma (Tu686) xenograft tumor (3-mm diameter). The ScFv-antibody recognizes the tumor biomarker EGFR. b In vivo SERS spectra were obtained, 5 h after injection, from the tumor site (red) and the liver site (blue) with 2-s signal integration (785 nm excitation). The spectra were background subtracted and shifted for better visualization.

Since such pioneering work by Nie’s group, in vivo SERS imaging of solid tumors has been the subject of intense investigations. Numerous advancements in terms of multiplexing capabilities, SEPs delivering to target tissues, reducing the toxicological impact, instrumentation designing and application of multimodal nanomaterials have been reported in the literature and will be discussed as follows.

Multiplexing

Similarly to in vitro SERS imaging of cancer cells, in vivo applications progressively extend the recognition lexicon beyond monoplex studies by preparing cocktails of different SEPs targeting multiple cancer membrane receptors (Dinish et al. 2014; Gao et al. 2015; Maiti et al. 2012; Zavaleta et al. 2009). Among others, Dinish et al. reported the in vivo triplex detection of cancer markers in xenograft breast cancer model (Dinish et al. 2014), even though the largest number of multiplex discrimination of SEPs in vivo was demonstrated for ten different nanoconstructs nonspecifically accumulated in the liver of a mouse (Zavaleta et al. 2009). Notably, the authors observed a linear correlation between the intensity of the SERS signal and the SEP concentration that allowed a semiquantitative prediction of a number of nanoparticles in the liver. However, it is worth stressing that due to limited penetration depth (5 mm), only a fraction of the liver was mapped.

Systemic vs. topical/local administration

The efficient and specific delivery of contrast agents to target cells and tissues not only plays a major role in the final quality and biological relevance of optical molecular images, but also has a tremendous toxicological impact (Kim et al. 2013). While active targeting methods have proven to significantly reduce the dissipation of SEPs to healthy tissues and organs with respect to passive approaches, still toxicity and clearance issues remain major concerns associated with the systemic route of administration (such as via intravenous injections). Thus, when allowed, alternative strategies to circumvent these problems have been exploited, including topical spray-like applications (Mallia et al. 2015; Zavaleta et al. 2013) and direct intratumoral injections (Dinish et al. 2014; Oseledchyk et al. 2017).

These administration routes also allow for shortening the relatively long accumulation time of systemic deliveries as well as reducing the amount of administered SEPs and the impact of nonspecific background signal (Mallia et al. 2015). Further, the intrinsic limitations imposed by the relatively large hydrodynamic size of SEPs (normally > 100 nm) on both the efficient circulation and extravasation from the bloodstream into cancer tissues, and the successful hepatic and renal clearance from the body, can be turned into a positive leverage in topical applications. In this case, the transfer of SEPs into the bloodstream is minimal, retaining local high concentration at the administered area (Jokerst et al. 2011; Mallia et al. 2015), while, such as in the case of intrarectally applications, the majority of the nanoparticle clearing is achieved after 24 h without systemic circulation crossing (Zavaleta et al. 2011, 2013).

Clearly, topical administrations of SEPs are not as much as valuable for deep tissue imaging as compared to their integration into surface imaging of tissues (Mallia et al. 2015), such as those revisiting, within the frame of SERS, the well-established “spray-and-image” procedure in endoscopy using chromogenic dyes to highlight pathologic lesions (Mallia et al. 2015).

A major issue to be faced in the direct application of SEPs to the tumor area is the residual presence of a large amount of unspecifically bound nanoparticles that require to be thoroughly washed off. However, the washing procedure is largely affected by tumor specificities, such as type and location (Mallia et al. 2015). As previously discussed, ratiometric approaches can address these limitations. A paradigmatic example is provided by the recent work of Oseledchyk et al. (2017), which devised a topically applied SERS ratiometric method to delineate ovarian cancer lesions as small as 370 μm in a murine model of human ovarian adenocarcinoma on the peritoneum and visceral surfaces after intraperitoneal injection. The unique behavior of metastatic diffusion of ovarian cancer, which initially spreads locally within the peritoneal cavity, paves the way for the local application of SEPs in the fast intraoperative detection of microscopic residual tumors during surgery. They employed two classes of SEPs consisting of gold nanostar cores labeled with resonant NIR dyes and coated with silica shells derivatized with either a folate receptor targeting antibody for targeted SEP (αFR-NPs, red) or with PEG for non-targeted SEP (nt-NPs, blue) (Fig. 9a). A direct classical least-squares (DCLS) model was developed to visualize the presence of the vibrational signature of each SEP and quantify their relative distributions down to concentrations of 300:3 fM. Regardless of the surface functionalization, SEPs adhere indiscriminately on peritoneal or visceral surfaces and also appear to remain trapped in anatomical crevices (Fig. 9b (ii) and (iii)). However, when presented as ratiometric maps (Fig. 9b (iv) and (v)), tumor lesions can be clearly identified in the tumor-bearing mice, while no positive signals were detected in the four healthy control animals. This is further confirmed via direct comparison with bioluminescence imaging (Fig. 9b (i)). Notably, the intraperitoneal administration was found to prevent systemic uptake of the nanoparticles, with negligible accumulations in the liver and spleen.

Adapted with permission from Oseledchyk et al. (2017). Copyright 2017, American Chemical Society

a Schematic depiction of the nanoparticle structure. The gold nanostar core is encapsulated in a silica shell containing either IR780 (red) or IR140 (blue) Raman reporter dye. NPs are then functionalized with either a folate receptor targeting antibody (αFR-Ab) for targeted NPs (αFR-NPs, red) or with PEG (polyethylene glycol) for non-targeted NPs (nt-NPs, blue). b Whole abdomen imaging of representative control (left) and tumor-bearing (right) mice. Bioluminescence (BLI) signal is shown in the top row. The direct classical least-squares (DCLS) maps of both targeted (2nd row) and non-targeted (3rd row) show a nonspecific distribution of both probes throughout the peritoneal cavity. A mixture of the two SEPs was injected i.p. Twenty minutes later, luciferin was injected retroorbitally. For the sake of clear visualization, the abdominal cavity was incised and washed with 60 ml of PBS, the entire abdomen was exposed, and the bowel resected for a better overview of the pelvic organs and the peritoneum. Topically applied surface-enhanced resonance Raman ratiometric spectroscopy (TAS3RS, 4th row) shows no positive regions in the control (left) and a strong correlation to BLI in tumor-bearing mice (right). Alternatively, the TAS3RS map can be visualized in a simplified manner for surgical guidance (bottom row), showing only regions with positive ratios in red. Reference standard solutions in Eppendorf vials were placed in the imaged field of view, with (1) indicating the vial containing αFR-NPs and (2) the vial containing nt-NPs.

It is worth noting that while the passive targeting strategy does not appear feasible for clinical applications in tumor imaging, it still offers a valuable and simple approach to characterize the optical response of SEPs in vivo.

Advancements in instrumentation

Traditionally, SERS imaging studies of tumors have been performed using static point detection devices (Jokerst et al. 2011; Keren et al. 2008; Maiti et al. 2012; Qian et al. 2008), where the laser is focused with a fixed angle onto a small spot on the tissue and, upon acquisition of the corresponding Raman spectrum on a linear (1D) array CCD, is then progressively scanned in two spatial dimensions over the interrogated area to finally generate the overall 2D Raman image. While demonstrating the tremendous analytical potential of the technique, this setup restricts the applicability to rather small tissue areas (unless exceedingly long integration times are applied or to the detriment of the necessary spatial resolution). Thus, major efforts have been devoted to the development of advanced instrumentations capable of addressing these issues (Bohndiek et al. 2013; Garai et al. 2015; Kang et al. 2016; Karabeber et al. 2014; Mallia et al. 2015; McVeigh et al. 2013; Mohs et al. 2010; Wang et al. 2016; Zavaleta et al. 2013).

For instance, Wilson and coworkers (Mallia et al. 2015; McVeigh et al. 2013) devised a wide-field SERS imaging approach for fast in vivo scanning of up to 2 cm2 of tissues. Here, all spatial points of the image were collected simultaneously on a 2D CCD at a single detection wavelength, while using specific band-pass filters to select Raman peaks of interest and to separate them from the background autofluorescence. The resulting images enable quantitative analysis at sub-picomolar concentrations of SEPs in vivo. On the other hand, Bonhndiek et al. (2013) designed a small animal Raman imaging instrument which provides high-speed scanning and quality spectral resolution, while retaining the high sensitivity and full spectral information of traditional point detection devices. In this system, a laser line is scanned in the x, y dimensions (> 6 cm2), while a high-sensitivity 2D electron-multiplying CCD collects both the spatial information for the y-axis (parallel to the entrance slit of the spectrometer) and the SERS spectral fingerprint (dispersed perpendicularly).

Handheld Raman devices were also combined with SEPs for in vivo intraoperative tumor imaging (Karabeber et al. 2014; Mohs et al. 2010) to provide a flexible instrumental tool, enabling the precise localization of small foci of the tumor which would otherwise remain undetected if scanning is only performed with the traditionally fixed angle setup.

The extremely rich molecular information provided by SERS imaging was also implemented with conventional white light endoscopy screening for cancer detection in the gastrointestinal tract by integrating fiberoptic-based Raman spectroscopy with clinical endoscopes (Garai et al. 2015; Zavaleta et al. 2013). High sensitivity, detecting SEPs at ca. 300 fM level with relatively low laser power and integration times, and multiplexing capabilities were demonstrated with this SERS-modified endoscope instrument.

The penetration depth limitation

In addition to long acquisition time and small field view, a third major limitation of conventional in vivo SERS imaging is imposed by the limited penetration depth (usually < 4–5 mm), resulting from high scattering and autofluorescence in animal tissues (Ntziachristos et al. 2003). This problem can, at least partially, be addressed by combining spatially offset Raman spectroscopy with SEPs, within the frame of what is defined as spatially offset surface-enhanced Raman scattering (SOSERS) spectroscopy (Stone et al. 2010, 2011; Xie et al. 2012). With SOSERS, depths up to 45–50 mm has been demonstrated in SEP-based imaging of animal tissues (Stone et al. 2011). For a detailed description of the technique, we refer the reader to the recently published review by Matousek and Stone (2016), who are among the pioneers of SORS spectroscopy.

Multimodal applications

As conceptual and instrumentational advancements in the standalone application of SERS imaging of cancers are progressively expanding this technique beyond the academic level to clinical settings, parallel efforts have been dedicated to the integration of SEPs into novel multifunctional hybrid materials with improved performance for multimodal applications (Conde et al. 2014; Gao et al. 2015; Henry et al. 2016; Qian et al. 2011; Von Maltzahn et al. 2009). With such complementary approaches, multimodal imaging technologies have been developed implementing SERS with other imaging techniques based on different physical effects such as fluorescence (Cui et al. 2011; Qian et al. 2011; Wang et al. 2014b), magnetic resonance (Gao et al. 2015; Ju et al. 2015) and photoacoustics (Bao et al. 2013; Chen et al. 2016; Dinish et al. 2015; Jokerst et al. 2012a; Kircher et al. 2012).

For instance, Qian et al. (2011) fabricated NIR fluorescent SEPs which allowed for the rapid area imaging of the tumor in living mice via fluorescent detection, while the high sensitivity and specificity of SERS enabled the definition of the margins of the cancerous tissue with high precision. Jokerst et al. (2012a) devised SEPs based on gold nanorods, yielding also intense photoacoustic (PA) signal, which were applied to image ovarian tumor subcutaneous xenograft models in vivo. In PA imaging, light pulses excite imaging agents creating a thermally induced pressure jump that launches ultrasonic waves, which are received by acoustic detectors to form images (Wang and Hu 2012). Such bimodal contrast agents simultaneously combine the high depth of penetration (up to 5 cm) of PA imaging for diagnostic or staging studies and the highly sensitive SERS detection for image-guided resection.

Gao et al. (2015) conjugated gadolinium (Gd) chelates onto the outer silica shell of SEPs, comprising gold nanostars as the plasmonic core and an NIR dye as a resonant SERS label, to additionally impart enhanced T1-magnetic resonance imaging capability (Liu and Zhang 2012) (Fig. 10a). Bimodal SEPs were intravenously injected into mice bearing MDA-MB-231 tumor. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI, Fig. 10b) revealed a dramatic brightening effect at the tumor area 30 min after systemic administration, due to nanoparticle accumulation via the EPR effect, though with limited spatial resolution and insufficient precision to outline tumor borders. As shown in Fig. 10c, intense SERS signal is also registered at different sites of the tumor. The results demonstrate that, as SERS offers remarkable sensitivity and resolution in displaying the heterogeneous intratumoral distribution of nanoparticles, whole-body MR imaging is able to determine the overall uptake of SEPs in the tumor. Further, the strong absorbance and low scattering of gold nanostars in the NIR tissue optical window were exploited in photothermal therapy (PPT) (Kennedy et al. 2011; Yuan et al. 2012). Figure 10d illustrates the thermal change in mice recorded by an infrared thermal camera during continuous laser irradiation. The temperature at the tumor spot rises up to ca. 57 °C, a value high enough to kill all kinds of cancer cells, while other regions not directly exposed to the NIR laser display minimal thermal increments.

Adapted with permission from Gao et al. (2015). Copyright 2015, Elsevier

a Schematic diagram of the structure design of the multimodal SEPs. A gold nanostar labeled with the SERS reporter DTTC is coated by an organosilica layer with abundant free thiol groups on the outer surface. The strong covalent bonding between –SH and maleimide facilitates the simultaneous conjugation of Gd chelates and PEG onto the outer surface of organosilica layer, forming the final trimodal particle. b In vivo T1-weighted MR images of a tumor site before and 30 min after intravenous injection of MGSNs (4 mgml−1, 100 μl). The tumor sites are marked with red circles. c SERS spectra of the tumor region after intravenously injected with multimodal SEPs, saline solution and skin near the tumor (785 nm excitation). SERS images at the two different sites (1 and 2) of the injected tumor produced by using the baseline corrected intensity of the SERS label band at 507 cm−1. Scale bar: 10 μm. d Infrared thermal images of tags injected tumor-bearing mice at different time points under laser irradiation at 808 nm.

In addition to photothermal heating, multimodal SEPs for effective molecular sensing and site-specific tumor treatment also include drug-loaded nanomaterials. For instance, Conde et al. (2014) reported the fabrication of SEPs conjugated with an FDA antibody–drug conjugate (Cetuximab) that specifically targets epidermal growth factor receptors (EGFR) on human cancer cells. Besides imparting specific recognition capabilities, the Ab turns off a main signaling cascade for cancer cells to proliferate and survive. Mice bearing a xenograft tumor mice model were subministered with these Ab-drug SEPs via tail injection. Continuous monitoring of the tumor area via in vivo SERS imaging revealed the inhibition of tumor progression and subsequent decrease of tumor size.

Conclusions and future perspective

SERS sensing with SERS-encoded particles has matured into a solid and reliable analytical technique for a wide variety of applications in cancer, including the characterization of a tumor cell, the IHC, resection guiding and localization of solid tumor bioimaging and staging.

However, there are still open challenges, mainly related to the reproducibility of the methods for substrate fabrication. This is especially relevant when dealing with the controlled formation of hot spots, the enhancement efficiency of which is extremely sensitive toward subtle differences of the nanostructure geometrical features. Additionally, although portable Raman spectrometers are available, most of the published reports are based on very sophisticated instruments that are not suited for routine analysis in clinical laboratories or hospitals. Thus, as demonstrated by many examples, the field of SERS codification has a great potential, in particular toward biomedical applications, but still remains open to new developments that will certainly continue amazing us in the near future.

Abbreviations

- Ab:

-

antibody

- BSA:

-

bovine serum albumin

- CCD:

-

charge-coupled device

- COINs:

-

composite organic–inorganic nanoparticles

- CTAB:

-

hexadecyltrimethylammonium bromide

- CTS:

-

computerized tomography scan

- DCLS:

-

direct classical least squares

- EGFR:

-

epidermal growth factor receptors

- EPR:

-

enhanced permeability and retention

- FDA:

-

Food and Drug Administration

- FISH:

-

fluorescent in situ hybridization

- HC/IHC:

-

histo/immunohistochemistry

- LSPR:

-

localized surface plasmon resonance

- MRI:

-

magnetic resonance imaging

- MUA:

-

mercaptoundecanoic acid

- NIPAM:

-

poly(N-isopropyl acrylamide)

- NIR:

-

near-infrared

- PA:

-

photoacoustic

- PCR:

-

polymerase chain reaction

- PEG:

-

polyethylene glycol

- PET:

-

positron emission tomography

- PTT:

-

photothermal therapy

- PVP:

-

polyvinylpyrrolidone

- SEPs:

-

SERS-encoded particles

- SERS:

-

surface-enhanced Raman scattering

- SORS:

-

spatially offset Raman scattering

- SOSERS:

-

spatially offset surface-enhanced Raman scattering

- WBC:

-

white blood cell

References

Allain LR, Vo-Dinh T. Surface-enhanced Raman scattering detection of the breast cancer susceptibility gene BRCA1 using a silver-coated microarray platform. Anal Chim Acta. 2002;469:149–54. doi:10.1016/S0003-2670(01)01537-9.

Altunbek M, Kuku G, Culha M. Gold nanoparticles in single-cell analysis for surface enhanced Raman scattering. Molecules. 2016. doi:10.3390/molecules21121617.

Alvarez-Puebla R, Liz-Marzán LM, García de Abajo FJ. Light concentration at the nanometer scale. J Phys Chem Lett. 2010;1:2428–34. doi:10.1021/jz100820m.

Alvarez-Puebla RA. Effects of the excitation wavelength on the SERS spectrum. J Phys Chem Lett. 2012;3:857–66. doi:10.1021/jz201625j.

Alvarez-Puebla RA, Contreras-Cáceres R, Pastoriza-Santos I, Pérez-Juste J, Liz-Marzán LM. Au@pNIPAM colloids as molecular traps for surface-enhanced, spectroscopic, ultra-sensitive analysis. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2009;48:138–43. doi:10.1002/anie.200804059.

Andreou C, Neuschmelting V, Tschaharganeh D-F, Huang C-H, Oseledchyk A, Iacono P, Karabeber H, Colen RR, Mannelli L, Lowe SW, Kircher MF. Imaging of liver tumors using surface-enhanced raman scattering nanoparticles. ACS Nano. 2016;10:5015–26. doi:10.1021/acsnano.5b07200.

Baena JR, Lendl B. Raman spectroscopy in chemical bioanalysis. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2004;8:534–9. doi:10.1016/j.cbpa.2004.08.014.

Bao C, Beziere N, del Pino P, Pelaz B, Estrada G, Tian F, Ntziachristos V, de la Fuente JM, Cui D. Gold nanoprisms as optoacoustic signal nanoamplifiers for in vivo bioimaging of gastrointestinal cancers. Small. 2013;9:68–74. doi:10.1002/smll.201201779.

Barbé C, Bartlett J, Kong L, Finnie K, Lin HQ, Larkin M, Calleja S, Bush A, Calleja G. Silica particles: a novel drug-delivery system. Adv Mater. 2004;16:1959–66. doi:10.1002/adma.200400771.

Bodelon G, Montes-García V, Fernández-Lõpez C, Pastoriza-Santos I, Pérez-Juste J, Liz-Marzán LM. Au@pNIPAM SERRS tags for multiplex immunophenotyping cellular receptors and imaging tumor cells. Small. 2015;11:4149–57. doi:10.1002/smll.201500269.

Bohndiek SE, Wagadarikar A, Zavaleta CL, Van De Sompel D, Garai E, Jokerst JV, Yazdanfar S, Gambhir SS. A small animal Raman instrument for rapid, wide-area, spectroscopic imaging. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110:12408–13. doi:10.1073/pnas.1301379110.

Catala C, Mir-Simon B, Feng X, Cardozo C, Pazos-Perez N, Pazos, E, Gómez-de Pedro S, Guerrini L, Soriano A, Vila J. Online SERS quantification of Staphylococcus Aureus and the application to diagnostics in human fluids. Adv Mater Technol. 2016;1:1600163. doi:10.1002/admt.201600163.

Chen H, Shao L, Li Q, Wang J. Gold nanorods and their plasmonic properties. Chem Soc Rev. 2013;42:2679–724. doi:10.1039/C2CS35367A.

Chen S, Bao C, Zhang C, Yang Y, Wang K, Chikkaveeraiah BV, Wang Z, Huang X, Pan F, Wang K, Zhi X, Ni J, de la Fuente JM, Tian J. EGFR antibody conjugated bimetallic Au@Ag nanorods for enhanced SERS-based tumor boundary identification, targeted photoacoustic imaging and photothermal therapy. Nano Biomed Eng. 2016;8:315–28. doi:10.5101/nbe.v8i4.p315-328.

Chourpa I, Lei FH, Dubois P, Manfait M, Sockalingum GD. Intracellular applications of analytical SERS spectroscopy and multispectral imaging. Chem Soc Rev. 2008;37:993–1000. doi:10.1039/B714732P.

Conde J, Bao C, Cui D, Baptista PV, Tian F. Antibody-drug gold nanoantennas with Raman spectroscopic fingerprints for in vivo tumour theranostics. J Control Release. 2014;183:87–93. doi:10.1016/j.jconrel.2014.03.045.

Cui Y, Zheng XS, Ren B, Wang R, Zhang J, Xia NS, Tian ZQ. Au@organosilica multifunctional nanoparticles for the multimodal imaging. Chem Sci. 2011;2:1463–9. doi:10.1039/c1sc00242b.

Dinish US, Balasundaram G, Chang YT, Olivo M. Actively targeted in vivo multiplex detection of intrinsic cancer biomarkers using biocompatible SERS nanotags. Sci Rep. 2014. doi:10.1038/srep04075.

Dinish US, Song Z, Ho CJH, Balasundaram G, Attia ABE, Lu X, Tang BZ, Liu B, Olivo M. Single molecule with dual function on nanogold: biofunctionalized construct for in vivo photoacoustic imaging and SERS biosensing. Adv Funct Mater. 2015;25:2316–25. doi:10.1002/adfm.201404341.

Fabris L. SERS tags: the next promising tool for personalized cancer detection? ChemNanoMat. 2016;2:249–58. doi:10.1002/cnma.201500221.

Feliu N, Sun X, Alvarez Puebla RA, Parak WJ. Quantitative particle–cell interaction: some basic physicochemical pitfalls. Langmuir. 2017. doi:10.1021/acs.langmuir.6b04629.

Gao Y, Li Y, Chen J, Zhu S, Liu X, Zhou L, Shi P, Niu D, Gu J, Shi J. Multifunctional gold nanostar-based nanocomposite: synthesis and application for noninvasive MR-SERS imaging-guided photothermal ablation. Biomaterials. 2015;60:31–41. doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2015.05.004.

Garai E, Sensarn S, Zavaleta CL, Loewke NO, Rogalla S, Mandella MJ, Felt SA, Friedland S, Liu JTC, Gambhir SS, Contag CH. A real-time clinical endoscopic system for intraluminal, multiplexed imaging of surface-enhanced Raman scattering nanoparticles. PLoS ONE. 2015;10:e0123185. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0123185.

Gerami P, Jewell SS, Morrison LE, Blondin B, Schulz J, Ruffalo T, Matushek Iv P, Legator M, Jacobson K, Dalton SR, Charzan S, Kolaitis NA, Guitart J, Lertsbarapa T, Boone S, LeBoit PE, Bastian BC. Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) as an ancillary diagnostic tool in the diagnosis of melanoma. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009;33:1146–56. doi:10.1097/PAS.0b013e3181a1ef36.

González-Solís JL, Luévano-Colmenero GH, Vargas-Mancilla J. Surface enhanced Raman spectroscopy in breast cancer cells. Laser Ther. 2013;22:37–42. doi:10.5978/islsm.13-OR-05.

Gown AM. Current issues in ER and HER2 testing by IHC in breast cancer. Mod Pathol. 2008;21:S8–15. doi:10.1038/modpathol.2008.34.

Gu P, Zhao YZ, Jiang LY, Zhang W, Xin Y, Han BH. Endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration for staging of lung cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:1389–96. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2008.11.043.

Henry A-I, Sharma B, Cardinal MF, Kurouski D, Van Duyne RP. Surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy biosensing: in vivo diagnostics and multimodal imaging. Anal Chem. 2016;88:6638–47. doi:10.1021/acs.analchem.6b01597.

Hoonejani MR, Pallaoro A, Braun GB, Moskovits M, Meinhart CD. Quantitative multiplexed simulated-cell identification by SERS in microfluidic devices. Nanoscale. 2015;7:16834–40. doi:10.1039/C5NR04147C.

Howes PD, Chandrawati R, Stevens MM. Colloidal nanoparticles as advanced biological sensors. Science. 2014;346:1247390. doi:10.1126/science.1247390.

Hu C, Shen J, Yan J, Zhong J, Qin W, Liu R, Aldalbahi A, Zuo X, Song S, Fan C, He D. Highly narrow nanogap-containing Au@Au core-shell SERS nanoparticles: size-dependent Raman enhancement and applications in cancer cell imaging. Nanoscale. 2016;8:2090–6. doi:10.1039/C5NR06919J.

Huang R, Harmsen S, Samii JM, Karabeber H, Pitter KL, Holland EC, Kircher MF. High precision imaging of microscopic spread of glioblastoma with a targeted ultrasensitive SERRS molecular imaging probe. Theranostics. 2016;6:1075–84. doi:10.7150/thno.13842.

Jain PK, Huang XH, El-Sayed IH, El-Sayed MA. Noble metals on the nanoscale: optical and photothermal properties and some applications in imaging, sensing, biology, and medicine. Acc Chem Res. 2008;41:1578–86. doi:10.1021/ar7002804.

Jenkins CA, Lewis PD, Dunstan PR, Harris DA. Role of Raman spectroscopy and surface enhanced Raman spectroscopy in colorectal cancer. World J Gastrointest Oncol. 2016;8:427–38. doi:10.4251/wjgo.v8.i5.427.

Jokerst JV, Cole AJ, Van De Sompel D, Gambhir SS. Gold nanorods for ovarian cancer detection with photoacoustic imaging and resection guidance via Raman imaging in living mice. ACS Nano. 2012a;6:10366–77. doi:10.1021/nn304347g.

Jokerst JV, Miao Z, Zavaleta C, Cheng Z, Gambhir SS. Affibody-functionalized gold–silica nanoparticles for Raman molecular imaging of the epidermal growth factor receptor. Small. 2011;7:625–33. doi:10.1002/smll.201002291.

Jokerst JV, Thangaraj M, Kempen PJ, Sinclair R, Gambhir SS. Photoacoustic imaging of mesenchymal stem cells in living mice via silica-coated gold nanorods. ACS Nano. 2012b;6:5920–30. doi:10.1021/nn302042y.

Ju K-Y, Lee S, Pyo J, Choo J, Lee J-K. Bio-inspired development of a dual-mode nanoprobe for MRI and Raman imaging. Small. 2015;11:84–9. doi:10.1002/smll.201401611.

Kang S, Wang Y, Reder NP, Liu JTC. Multiplexed molecular imaging of biomarker-targeted SERS nanoparticles on fresh tissue specimens with channel-compressed spectrometry. PLoS ONE. 2016;11:e0163473. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0163473.

Karabeber H, Huang R, Iacono P, Samii JM, Pitter K, Holland EC, Kircher MF. Guiding brain tumor resection using surface-enhanced Raman scattering nanoparticles and a hand-held raman scanner. ACS Nano. 2014;8:9755–66. doi:10.1021/nn503948b.

Kennedy LC, Bickford LR, Lewinski NA, Coughlin AJ, Hu Y, Day ES, West JL, Drezek RA. A new era for cancer treatment: gold-nanoparticle-mediated thermal therapies. Small. 2011;7:169–83. doi:10.1002/smll.201000134.

Keren S, Zavaleta C, Cheng Z, de la Zerda A, Gheysens O, Gambhir SS. Noninvasive molecular imaging of small living subjects using Raman spectroscopy. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2008;105:5844–9. doi:10.1073/pnas.0710575105.

Khan AH, Sadroddiny E. Application of immuno-PCR for the detection of early stage cancer. Mol Cell Probes. 2016;30:106–12. doi:10.1016/j.mcp.2016.01.010.

Kim ST, Saha K, Kim C, Rotello VM. The role of surface functionality in determining nanoparticle cytotoxicity. Acc Chem Res. 2013;46:681–91. doi:10.1021/ar3000647.

Kircher MF, De La Zerda A, Jokerst JV, Zavaleta CL, Kempen PJ, Mittra E, Pitter K, Huang R, Campos C, Habte F, Sinclair R, Brennan CW, Mellinghoff IK, Holland EC, Gambhir SS. A brain tumor molecular imaging strategy using a new triple-modality MRI-photoacoustic-Raman nanoparticle. Nat Med. 2012;18:829–34. doi:10.1038/nm.2721.

Kneipp J. Interrogating cells, tissues, and live animals with new generations of surface-enhanced Raman scattering probes and labels. ACS Nano. 2017;11:1136–41. doi:10.1021/acsnano.7b00152.

Koboldt DC, Steinberg KM, Larson DE, Wilson RK, Mardis ER. The next-generation sequencing revolution and its impact on genomics. Cell. 2013;155:27–38. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2013.09.006.

Kong K, Kendall C, Stone N, Notingher I. Raman spectroscopy for medical diagnostics—from in vitro biofluid assays to in vivo cancer detection. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2015;89:121–34. doi:10.1016/j.addr.2015.03.009.

Kuhl CK, Schrading S, Leutner CC, Morakkabati-Spitz N, Wardelmann E, Fimmers R, Kuhn W, Schild HH. Mammography, breast ultrasound, and magnetic resonance imaging for surveillance of women at high familial risk for breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:8469–76. doi:10.1200/jco.2004.00.4960.

Lasagna-Reeves C, Gonzalez-Romero D, Barria MA, Olmedo I, Clos A, Sadagopa Ramanujam VM, Urayama A, Vergara L, Kogan MJ, Soto C. Bioaccumulation and toxicity of gold nanoparticles after repeated administration in mice. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2010;393:649–55. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.02.046.

Ru EC, Etchegoin PG. Principles of surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy. Elsevier. 2009. doi:10.1016/B978-0-444-52779-0.X0001-3.

Liu Y, Zhang N. Gadolinium loaded nanoparticles in theranostic magnetic resonance imaging. Biomaterials. 2012;33:5363–75. doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2012.03.084.

Lutz BR, Dentinger CE, Nguyen LN, Sun L, Zhang J, Allen AN, Chan S, Knudsen BS. Spectral analysis of multiplex Raman probe signatures. ACS Nano. 2008;2:2306–14. doi:10.1021/nn800243g.

MacParland SA, Tsoi KM, Ouyang B, Ma X-Z, Manuel J, Fawaz A, Ostrowski MA, Alman BA, Zilman A, Chan WCW, McGilvray ID. Phenotype determines nanoparticle uptake by human macrophages from liver and blood. ACS Nano. 2017;11:2428–43. doi:10.1021/acsnano.6b06245.

Maeda H, Nakamura H, Fang J. The EPR effect for macromolecular drug delivery to solid tumors: improvement of tumor uptake, lowering of systemic toxicity, and distinct tumor imaging in vivo. Adv Drug Deliv Rev. 2013;65:71–9. doi:10.1016/j.addr.2012.10.002.

Maiti KK, Dinish US, Samanta A, Vendrell M, Soh KS, Park SJ, Olivo M, Chang YT. Multiplex targeted in vivo cancer detection using sensitive near-infrared SERS nanotags. Nano Today. 2012;7:85–93. doi:10.1016/j.nantod.2012.02.008.

Mallia RJ, McVeigh PZ, Fisher CJ, Veilleux I, Wilson BC. Wide-field multiplexed imaging of EGFR-targeted cancers using topical application of NIR SERS nanoprobes. Nanomedicine. 2015;10:89–101. doi:10.2217/nnm.14.80.

Matousek P, Stone N. Development of deep subsurface Raman spectroscopy for medical diagnosis and disease monitoring. Chem Soc Rev. 2016;45:1794–802. doi:10.1039/c5cs00466g.

McVeigh PZ, Mallia RJ, Veilleux I, Wilson BC. Widefield quantitative multiplex surface enhanced Raman scattering imaging in vivo. J Biomed Opt. 2013. doi:10.1117/1.JBO.18.4.046011.

Meacham CE, Morrison SJ. Tumour heterogeneity and cancer cell plasticity. Nature. 2013;501:328–37. doi:10.1038/nature12624.

Mir-Simon B, Reche-Perez I, Guerrini L, Pazos-Perez N, Alvarez-Puebla RA. Universal one-pot and scalable synthesis of SERS encoded nanoparticles. Chem Mater. 2015;27:950–8. doi:10.1021/cm504251h.

Mohs AM, Mancini MC, Singhal S, Provenzale JM, Leyland-Jones B, Wang MD, Nie SM. Hand-held spectroscopic device for in vivo and intraoperative tumor detection: contrast enhancement, detection sensitivity, and tissue penetration. Anal Chem. 2010;82:9058–65. doi:10.1021/ac102058k.

Morla-Folch J, Gisbert-Quilis P, Masetti M, Garcia-Rico E, Alvarez-Puebla RA, Guerrini L. Conformational sers classification of k-RAS point mutations for cancer diagnostics. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2017;56:2381–5. doi:10.1002/anie.201611243.

Morla-Folch J, Guerrini L, Pazos-Perez N, Arenal R, Alvarez-Puebla RA. Synthesis and optical properties of homogeneous nanoshurikens. ACS Photonics. 2014;1:1237–44. doi:10.1021/ph500348h.

Morla-Folch J, Xie H-N, Alvarez-Puebla RA, Guerrini L. Fast optical chemical and structural classification of RNA. ACS Nano. 2016;10:2834–42. doi:10.1021/acsnano.5b07966.

Nima ZA, Mahmood M, Xu Y, Mustafa T, Watanabe F, Nedosekin DA, Juratli MA, Fahmi T, Galanzha EI, Nolan JP, Basnakian AG, Zharov VP, Biris AS. Circulating tumor cell identification by functionalized silver-gold nanorods with multicolor, super-enhanced SERS and photothermal resonances. Sci Rep. 2014. doi:10.1038/srep04752.

Nolan JP, Duggan E, Liu E, Condello D, Dave I, Stoner SA. Single cell analysis using surface enhanced Raman scattering (SERS) tags. Methods. 2012;57:272–9. doi:10.1016/j.ymeth.2012.03.024.

Ntziachristos V, Bremer C, Weissleder R. Fluorescence imaging with near-infrared light: new technological advances that enable in vivo molecular imaging. Eur Radiol. 2003;13:195–208. doi:10.1007/s00330-002-1524-x.

Oseledchyk A, Andreou C, Wall MA, Kircher MF. Folate-targeted surface-enhanced resonance Raman scattering nanoprobe ratiometry for detection of microscopic ovarian cancer. ACS Nano. 2017;11:1488–97. doi:10.1021/acsnano.6b06796.

Pallaoro A, Braun GB, Moskovits M. Quantitative ratiometric discrimination between noncancerous and cancerous prostate cells based on neuropilin-1 overexpression. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2011;108:16559–64. doi:10.1073/pnas.1109490108.

Pazos-Perez N, Pazos E, Catala C, Mir-Simon B, Gómez-de Pedro S, Sagales J, Villanueva C, Vila J, Soriano A, García de Abajo FJ, Alvarez-Puebla RA. Ultrasensitive multiplex optical quantification of bacteria in large samples of biofluids. Sci Rep. 2016;6:29014. doi:10.1038/srep29014.

Pazos-Perez N, Wagner CS, Romo-Herrera JM, Liz-Marzán LM, García de Abajo FJ, Wittemann A, Fery A, Alvarez-Puebla RA. Organized plasmonic clusters with high coordination number and extraordinary enhancement in surface-enhanced Raman scattering (SERS). Angew Chem Int Ed. 2012;51:12688–93. doi:10.1002/anie.201207019.

Pearce MS, Salotti JA, Little MP, McHugh K, Lee C, Kim KP, Howe NL, Ronckers CM, Rajaraman P, Craft AW, Parker L, Berrington de González A. Radiation exposure from CT scans in childhood and subsequent risk of leukaemia and brain tumours: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2012;380:499–505. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60815-0.

Pedrol E, Garcia-Algar M, Massons J, Nazarenus M, Guerrini L, Martínez J, Rodenas A, Fernandez-Carrascal A, Aguiló M, Estevez LG, Calvo I, Olano-Daza A, Garcia-Rico E, Díaz F, Alvarez-Puebla RA. Optofluidic device for the quantification of circulating tumor cells in breast cancer. Sci Rep. 2017;7:3677. doi:10.1038/s41598-017-04033-9.

Pelaz B, Alexiou C, Alvarez-Puebla RA, Alves F, Andrews AM, Ashraf S, Balogh LP, Ballerini L, Bestetti A, Brendel C, Bosi S, Carril M, Chan WCW, Chen C, Chen X, Chen X, Cheng Z, Cui D, Du J, Dullin C, Escudero A, Feliu N, Gao M, George M, Gogotsi Y, Grünweller A, Gu Z, Halas NJ, Hampp N, Hartmann RK, Hersam MC, Hunziker P, Jian J, Jiang X, Jungebluth P, Kadhiresan P, Kataoka K, Khademhosseini A, Kopeček J, Kotov NA, Krug HF, Lee DS, Lehr C-M, Leong KW, Liang X-J, Ling Lim M, Liz-Marzán LM, Ma X, Macchiarini P, Meng H, Möhwald H, Mulvaney P, Nel AE, Nie S, Nordlander P, Okano T, Oliveira J, Park TH, Penner RM, Prato M, Puntes V, Rotello VM, Samarakoon A, Schaak RE, Shen Y, Sjöqvist S, Skirtach AG, Soliman MG, Stevens MM, Sung H-W, Tang BZ, Tietze R, Udugama BN, VanEpps JS, Weil T, Weiss PS, Willner I, Wu Y, Yang L, Yue Z, Zhang Q, Zhang Q, Zhang X-E, Zhao Y, Zhou X, Parak WJ. Diverse applications of nanomedicine. ACS Nano. 2017;11:2313–81. doi:10.1021/acsnano.6b06040.

Polo E, Collado M, Pelaz B, del Pino P. Advances toward more efficient targeted delivery of nanoparticles in vivo: understanding interactions between nanoparticles and cells. ACS Nano. 2017;11:2397–402. doi:10.1021/acsnano.7b01197.

Polo E, del Pino P, Pelaz B, Grazu V, de la Fuente JM. Plasmonic-driven thermal sensing: ultralow detection of cancer markers. Chem Commun. 2013;49:3676–8. doi:10.1039/C3CC39112D.

Qian J, Jiang L, Cai F, Wang D, He S. Fluorescence-surface enhanced Raman scattering co-functionalized gold nanorods as near-infrared probes for purely optical in vivo imaging. Biomaterials. 2011;32:1601–10. doi:10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.10.058.

Qian XM, Peng XH, Ansari DO, Yin-Goen Q, Chen GZ, Shin DM, Yang L, Young AN, Wang MD, Nie SM. In vivo tumor targeting and spectroscopic detection with surface-enhanced Raman nanoparticle tags. Nat Biotech. 2008;26:83–90. doi:10.1038/nbt1377.

Rodríguez-Lorenzo L, Álvarez-Puebla RA, Pastoriza-Santos I, Mazzucco S, Stéphan O, Kociak M, Liz-Marzán LM, García de Abajo FJ. Zeptomol detection through controlled ultrasensitive surface-enhanced Raman scattering. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:4616–8. doi:10.1021/ja809418t.

Rodríguez-Lorenzo L, de la Rica R, Álvarez-Puebla RA, Liz-Marzán LM, Stevens MM. Plasmonic nanosensors with inverse sensitivity by means of enzyme-guided crystal growth. Nat Mater. 2012;11:604–7. doi:10.1038/nmat3337.

Romo-Herrera JM, Alvarez-Puebla RA, Liz-Marzan LM. Controlled assembly of plasmonic colloidal nanoparticle clusters. Nanoscale. 2011;3:1304–15. doi:10.1039/c0nr00804d.

Sackmann EK, Fulton AL, Beebe DJ. The present and future role of microfluidics in biomedical research. Nature. 2014;507:181–9. doi:10.1038/nature13118.

Schlücker S. Surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy: concepts and chemical applications. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2014;53:4756–95. doi:10.1002/anie.201205748.

Schramm M, Wrobel C, Born I, Kazimirek M, Pomjanski N, William M, Kappes R, Gerharz CD, Biesterfeld S, Bocking A. Equivocal cytology in lung cancer diagnosis. Cancer Cytopathol. 2011;119:177–92. doi:10.1002/cncy.20142.

Schumacher TN, Scheper W. A liquid biopsy for cancer immunotherapy. Nat Med. 2016;22:340–1. doi:10.1038/nm.4074.

Sha MY, Xu H, Penn SG, Cromer R. SERS nanoparticles: a new optical detection modality for cancer diagnosis. Nanomedicine. 2007;2:725–34. doi:10.2217/17435889.2.5.725.

Shields CW, Reyes CD, Lopez GP. Microfluidic cell sorting: a review of the advances in the separation of cells from debulking to rare cell isolation. Lab Chip. 2015;15:1230–49. doi:10.1039/c4lc01246a.

Silvestri GA, Gonzalez AV, Jantz MA, Margolis ML, Gould MK, Tanoue LT, Harris LJ, Detterbeck FC. Methods for staging non-small cell lung cancer: diagnosis and management of lung cancer, 3rd ed: American college of chest physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest. 2013;143:e211S–50S. doi:10.1378/chest.12-2355.

Siravegna G, Marsoni S, Siena S, Bardelli A. Integrating liquid biopsies into the management of cancer. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2017. doi:10.1038/nrclinonc.2017.14.

Smith AM, Mancini MC, Nie S. Bioimaging: second window for in vivo imaging. Nat Nano. 2009;4:710–1. doi:10.1038/nnano.2009.326.

Stone N, Faulds K, Graham D, Matousek P. Prospects of deep Raman spectroscopy for noninvasive detection of conjugated surface enhanced resonance Raman scattering nanoparticles buried within 25 mm of mammalian tissue. Anal Chem. 2010;82:3969–73. doi:10.1021/ac100039c.

Stone N, Kerssens M, Lloyd GR, Faulds K, Graham D, Matousek P. Surface enhanced spatially offset Raman spectroscopic (SESORS) imaging—the next dimension. Chem Sci. 2011;2:776–80. doi:10.1039/C0SC00570C.

Subik K, Lee J-F, Baxter L, Strzepek T, Costello D, Crowley P, Xing L, Hung M-C, Bonfiglio T, Hicks DG, Tang P. The expression patterns of ER, PR, HER2, CK5/6, EGFR, Ki-67 and AR by immunohistochemical analysis in breast cancer cell lines. Breast Cancer. 2010;4:35–41.

Taylor J, Huefner A, Li L, Wingfield J, Mahajan S. Nanoparticles and intracellular applications of surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy. Analyst. 2016;141:5037–55. doi:10.1039/c6an01003b.

Verma S, Turkbey B, Muradyan N, Rajesh A, Cornud F, Haider MA, Choyke PL, Harisinghani M. Overview of dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI in prostate cancer diagnosis and management. Am J Roentgenol. 2012;198:1277–88. doi:10.2214/AJR.12.8510.

Vilar-Vidal N, Bonhommeau S, Talaga D, Ravaine S. One-pot synthesis of gold nanodimers and their use as surface-enhanced Raman scattering tags. New J Chem. 2016;40:7299–302. doi:10.1039/c6nj01389a.

Von Maltzahn G, Centrone A, Park JH, Ramanathan R, Sailor MJ, Alan Hatton T, Bhatia SN. SERS-coded cold nanorods as a multifunctional platform for densely multiplexed near-infrared imaging and photothermal heating. Adv Mater. 2009;21:3175–80. doi:10.1002/adma.200803464.

Wang LV, Hu S. Photoacoustic tomography: in vivo imaging from organelles to organs. Science. 2012;335:1458–62. doi:10.1126/science.1216210.

Wang Y, Chen L, Liu P. Biocompatible triplex Ag@SiO2@mTiO2 core-shell nanoparticles for simultaneous fluorescence-SERS bimodal imaging and drug delivery. Chem Eur J. 2012;18:5935–43. doi:10.1002/chem.201103571.

Wang Y, Kang S, Khan A, Ruttner G, Leigh SY, Murray M, Abeytunge S, Peterson G, Rajadhyaksha M, Dintzis S, Javid S, Liu JTC. Quantitative molecular phenotyping with topically applied SERS nanoparticles for intraoperative guidance of breast cancer lumpectomy. Sci Rep. 2016. doi:10.1038/srep21242.

Wang Y, Schlucker S. Rational design and synthesis of SERS labels. Analyst. 2013;138:2224–38. doi:10.1039/C3AN36866A.

Wang YW, Khan A, Som M, Wang D, Chen Y, Leigh SY, Meza D, McVeigh PZ, Wilson BC, Liu JTC. Rapid ratiometric biomarker detection with topically applied SERS nanoparticles. Technology. 2014a;2:118–32. doi:10.1142/S2339547814500125.

Wang Z, Zong S, Chen H, Wang C, Xu S, Cui Y. SERS-fluorescence joint spectral encoded magnetic nanoprobes for multiplex cancer cell separation. Adv Healthc Mater. 2014b;3:1889–97. doi:10.1002/adhm.201400092.

Weissleder R, Nahrendorf M, Pittet MJ. Imaging macrophages with nanoparticles. Nat Mater. 2014;13:125–38. doi:10.1038/nmat3780.

Xie HN, Stevenson R, Stone N, Hernandez-Santana A, Faulds K, Graham D. Tracking bisphosphonates through a 20 mm thick porcine tissue by using surface-enhanced spatially offset Raman spectroscopy. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2012;51:8509–11. doi:10.1002/anie.201203728.

Yuan H, Fales AM, Vo-Dinh T. TAT peptide-functionalized gold nanostars: enhanced intracellular delivery and efficient nir photothermal therapy using ultralow irradiance. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:11358–61. doi:10.1021/ja304180y.

Zavaleta CL, Garai E, Liu JTC, Sensarn S, Mandella MJ, Van de Sompel D, Friedland S, Van Dam J, Contag CH, Gambhir SS. A Raman-based endoscopic strategy for multiplexed molecular imaging. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2013;110:E2288–97. doi:10.1073/pnas.1211309110.