Abstract

Background

The human papilloma virus (HPV) infections were addressed with two FDA-approved HPV vaccines: quadrivalent and bivalent vaccine. The objective of this manuscript is to determine the safety of the HPV vaccine.

Results

A search of PubMed articles for “human papillomavirus vaccine” was used to identify all-type HPV clinical studies prior to October 2014. A refined search of clinical trials, multicenter studies, and randomized studies were screened for only randomized controlled trials comparing HPV vaccine to controls (saline placebo or aluminum derivatives). Studies were limited to the two FDA-approved vaccines. Following PRISMA guidelines, the literature review rendered 13 publications that met inclusion/ exclusion criteria. Gender was limited to females in 10 studies and males in 1 study. Two studies included both males and females. Of the 11,189 individuals in 7 publications reporting cumulative, all-type adverse events (AE), the AE incidence of 76.52 % (n = 4544) in the vaccinated group was statistically significantly higher than 67.57 % (n = 3548) in the control group (p < 0.001). The most common AE were injection-site reactions. On the other hand, systemic symptoms did not statistically significantly differ between the vaccination cohort (35.28 %, n = 3351) and the control cohort (36.14 %, n = 3198) (p = 0.223). The pregnancy/ perinatal outcomes rendered no statistically significant difference between the vaccine group and control group.

Conclusion

Because the statistically significantly higher incidence of AE in the HPV vaccine group was primarily limited to injection-site reactions, the vaccinations are safe preventative measures in both males and females.

Résumé

Contexte

Les infections dues au papillomavirus humain (HPV) ont été prises en compte par deux vaccins HPV approuvés par la FDA (Food and Drug Administration: Agence américaine des Produits Alimentaires et Médicamenteux): les vaccins quadrivalent et bivalent. L’objectif de cet article est de déterminer la sécurité du vaccin HPV.

Résultats

Une recherche dans PubMed des articles sur “human papillomavirus vaccine” a été utilisée pour identifier tout type d’études cliniques sur HPV antérieures à Octobre 2014. Une recherche affinée des essais cliniques, des études multicentriques et des études randomisées n’a été menée que pour les essais randomisés avec groupe témoin comparant le vaccin HPV à un témoin (solution saline comme placébo ou dérivés de l’aluminium). Seules les études utilisant les deux vaccins approuvés par la FDA ont été retenues. En suivant les recommandations PRISMA, la revue de la littérature a retrouvé 13 publications conformes aux critères d’inclusion/exclusion. Dix études impliquaient les femmes et une les hommes. Deux études incluaient à la fois des femmes et des hommes. Sur les 11 189 personnes de 7 articles rapportant tout type d’effets indésirables (EI) cumulés, l’incidence d’EI de 76,52% (n=4544) dans le groupe vacciné était significativement plus élevée que l’incidence de 67,57% dans le groupe témoin (p<0,001). Les réactions sur le site d’injection étaient l’EI le plus courant. D’autre part, les symptômes systémiques ne différaient pas significativement entre la cohorte vaccinée (35,28%; n=3351) et la cohorte témoin (36,14%; n=3198) (p=0,223). Les issues des grossesses et les issues périnatales n’étaient pas significativement différentes entre groupe vacciné et groupe placébo.

Conclusion

Comme l’incidence significativement plus élevée d’EI dans le groupe vacciné se limitait principalement aux réactions sur le site d’injection, les vaccinations sont des mesures préventives sans danger pour les hommes et les femmes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The human papillomavirus (HPV) is an important preventable cause of sexually-transmitted disease and squamous cell carcinomas. HPV types 16 and 18 have been implicated in cervical, anal, vaginal, and vulvar cancers, while types 6 and 11 cause anogenital warts. Between 2003 and 2004, the overall HPV prevalence was 26.8 % [1]. Moreover, the prevalence of HPV infections statistically significantly increased with each year of age from 14 to 24 (p < 0.001) [1]. The National Cancer Institute independently developed the HPV vaccine, which was subsequently sold to Merek & Co and GlaxoSmithKline for randomized controlled trials (RCTs). The HPV vaccine studies were subsequently marketed as a novel intervention to curtail the infection’s oncologic aptitude. Years of clinical trials by the pharmaceutical companies have materialized into two Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved HPV vaccine. First, Gardasil or Silgard (Merck & Co) is a human recombinant papillomavirus vaccine- quadrivalent types 6,11,16,18. Second, Cervarix (GlaxoSmithKline) is a bivalent human papillomavirus vaccine- types 16, 18. While the efficacy of both vaccines has been verified in randomized control studies (RCT) [2–4], the safety of these prophylactic interventions has been strongly contested in the outpatient settings.

Methods

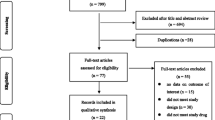

The literature review followed Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Fig. 1) [5]. A search of PubMed articles for “human papillomavirus vaccine” was used to identify all-type HPV clinical studies prior to October 2014. A refined search of clinical trials, multicenter studies, and randomized studies were screened for only randomized controlled trials comparing HPV vaccine to controls (saline placebo or aluminum derivatives). With a compilation of previously published RCTs, we compared adverse effects from the HPV vaccine versus control injection. The primary endpoint was to determine the safety of the HPV vaccine. The literature review outlined in Table 1 includes the primary author, publication year, number study participants, description of the study population, type of adverse events, number of vaccinated and unvaccinated participants for whom adverse events (AE) are reported, and P value comparison between the two cohorts.

Both solicited and unsolicited adverse events were included in the review. AE were determined by the article investigator as possibly, probably, or definitely related to the vaccine. AE were categorized according to the discrete time intervals during which the unintended outcome occurred. HPV vaccine was typically administered in a 3-dose schedule. The number of adverse events was expressed as a proportion of subjects, rather than the proportion of doses.

Inclusion/ Exclusion criteria

Only randomized controlled trials were included in the present article. Vaccination groups were limited to the two FDA-approved HPV vaccinations: (1) quadrivalent HPV-6,11,16,18 L1 virus-like particle (VLP) vaccine; (2) HPV-16,18 Adjuvant System (AS) 04 vaccine. Vaccines are composed of either quadrivalent or bivalent antigens plus either an amorphous aluminum hydroxyphosphate sulfate (AAHS) adjuvant or aluminum hydroxide [Al(OH)3]. Control cohorts were limited to solutions containing either (A) saline placebo; or (B) identical components to those in the vaccine, with the exception of the HPV antigens. Twelve articles included AAHS or Al(OH)3 placebo [2, 3, 6–15]; however, Reisinger et al. utilized a saline placebo [16]. RCTs with hepatitis A and/or hepatitis B vaccine controls were excluded [17–29]. Control groups without injections were also removed from the literature review insomuch as the study design would interfere with the blinded schema and become susceptible to a reporting bias/ information bias [30]. Randomized controlled trials without mention of adverse events and/or non-clinical RCTs were excluded from the literature review. Repeat studies, ad hoc subgroup analysis, and pooled analyses were similarly excluded [4, 31–38]. Lastly, AE expressed as a percentage of doses, rather than a percentage of study participants, were not included in Table 1 [13].

Statistical analysis

Demographic information was described using summary statistics. The percent of subjects who experienced an AE in the vaccine group were compared to the placebo counterparts with Chi-squared (χ2) tests. Stata (version 12.0, College Station, TX, USA) and GraphPad Software were used for statistical interpretations of the raw data. Statistical significance was set a p ≤ 0.05.

Results

The PRISMA flow diagram detailing the selection process is presented in Fig. 1. The most common reason for exclusion was non-randomized, clinical-controlled trials (n = 230). Of the 86 RCTs, the most prevalent exclusion criteria was non-clinical studies/ studies without mention of AE (n = 29), followed by HPV RCTs with vaccines other than the quadrivalent HPV-6,11,16,18 L1 VLP or bivalent HPV-16,18 AS04. Following PRISMA guidelines, the literature review rendered 13 publications that met the aforementioned inclusion/ exclusion criteria [2, 3, 6–16, 39]. Most clinical studies were sufficiently powered to detect a statistically significant difference between the vaccination and control cohorts, with the smallest study population of 150 women in the RCT by Denny et al. [15].

In the present literature review, the study population consisted of 31,289 subjects, 98.87 % of whom (n = 30,934) had follow-up data available for documentation of adverse events. Gender was limited to females in 10 studies [2, 3, 6–10, 13–15] and males in 1 study [12]. Two studies included both males and females [11, 16]. Ages ranged from 9 to 45 years. The sample populations were derived from multi-national institutions, with the exception of a Chinese trial by Ngan et al. and a Japanese trial by Yoshikawa et al. [10, 14]. Similarly, all trials were multi-center studies, with the exception of a single-institutional RCT in Hong Kong [10]. The most common study inclusion criteria were ≤4–6 lifetime sexual partners, no abnormal Papanicolaou smears, non-pregnant, and no cervical infections/ anogenital warts. Women were encouraged to utilize effective contraception. Two studies specifically focused on Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV)-seropositive participants [11, 15].

Of the 11,189 individuals in 7 publications reporting cumulative, all-type adverse events[7, 8, 11, 12, 14–16], the AE incidence of 76.52 % (n = 4544) in the vaccinated group was statistically significantly higher than 67.57 % (n = 3548) in the placebo group (p < 0.001). The most common AE were injection-site reactions. In fact, of the 18,348 participants in 9 reporting articles [2, 3, 6–8, 11, 12, 14, 16], the 77.43 % of vaccinated subjects (n = 7355) who experienced all-type injection-site reactions was statistically significantly higher than the 67.70 % of control subjects (n = 5991) (p < 0.001). The most common injection-site reactions were pain, induration, and erythema. On the other hand, systemic symptoms did not statistically significantly differ between the vaccination cohort (35.28 %, n = 3351) and the placebo cohort (36.14 %, n = 3198) (p = 0.223). The most common systemic symptoms included fatigue, headache, and fever. Ten articles (n = 30,398) reported serious adverse events [2, 3, 6–9, 12–14, 16]. The incidence of 0.15 % (n = 23) in the vaccination division did not statistically significantly differ from 0.14 % (n = 20) in the control counterparts (p = 0.774). Of the 23 subjects experiencing serious AE, 17 (73.91 %) were attributable to malaria infection, unrelated to the vaccine, in the sub-Saharan Africa study by Sow et al. [13]. Serious AE in the remaining 6 vaccinated subjects included bronchospasm, acute pancreatitis, lymph node tuberculosis, gastroenteritis, headache, and hypertension. Only 4 patients (0.03 %) in the vaccine unit [6, 12] and 7 patients (0.06 %) in the control unit [6, 7, 12, 14] discontinued the study due to adverse events (p = 0.367). Of the four elective terminations in the vaccine group, three men cited vaccine-related malaise, headache, and pyrexia in the publications by Giuliano et al. [12, 39] and Yoshikawa et al. [14], whereas one woman experienced a spontaneous abortion in the publication by Harper et al. [6], thought to be unrelated to the vaccine. Twelve and seventeen individuals died in the vaccine and control groups, respectively. Causes of death in the vaccine cohort included pneumonia and sepsis, overdose of an illicit drug, motor vehicle accident (6 persons), pulmonary embolism, infective thrombosis, homicide, and suicide, none of which were linked with the vaccine [2, 3, 12].

Ngan et al. and Sow et al. reported new-onset chronic disease/ autoimmune disease following injection with drug vs control [10, 13]. Of the 966 enrollees in the two studies, the rate of 3.36 % in the vaccine randomization did not statistically significantly differ from 4.85 % in the control randomization (p = 0.246). Lastly, while effective contraception and non-pregnancy represented key selection criteria for most RCTs in the present literature review, pregnancy was reported in the follow up period. Birth complications included one spontaneous abortion, nine elective abortions, and one death of a premature infant in the vaccination cohort in comparison to one spontaneous abortion, one miscarriage, one ectopic pregnancy, three elective abortions, and one death of a premature infant in the control cohort. None of these experiences were liked with the injections. The pregnancy/ perinatal outcomes from the Females United to Unilaterally Reduce Endo/Ectocervical Disease (FUTURE) I (Merck V501-013), FUTURE II (Merck V501-015), Merck V501-016, and Merck V501-018 RCTs were combined in the Appendix in the FUTURE II study (Merck V501-016, 018 did not meet selection criteria in this literature review) [38]. In brief, no statistically significant difference was observed between the vaccine group and control group.

Discussion

In 1796, an English physician, Edward Jenner, performed the first vaccination by inoculating an 8-year-old boy with pus from a cowpox lesion [40]. Despite the growing safety concerns for his experimental design of a smallpox vaccine, Dr. Jenner published his conclusions in a landmark text in the annals of medicine: Inquiry into the Causes and Effects of the Variolae Vaccine [41]. Since the development of Dr. Jenner’s time-honored work, vaccine production over the ensuing centuries have ushered in a new era of preventive medicine; nevertheless, safety concerns for vaccination of children and young adults still remains the greatest barrier to these scientific advancements. A testament to this belief today, the most recent FDA-approved vaccines, Gardasil/Silgard and Cervarix, have met significant resistance owing to the fear of unknown side-effects. In this literature review, we compared adverse effects from the HPV vaccine versus control injection from a compilation of published randomized controlled trials. The primary endpoint of this study was to determine the safety of the HPV vaccine.

In the present literature review, the vaccine was well-tolerated without undue AE. All-type AE and injection-related AE were the only two parameters with a significantly higher rate in the HPV vaccinated subjects, whereas systemic events, serious AE, and death did not differ. The vaccine cohort (76.52 %) carried an approximately 10 % higher rate of all-type adverse events in comparison to the control cohort (67.57 %) (p < 0.001). These results corroborate a sub-analysis by Moreira et al. [39], who reviewed AE in the 4065 males enrolled in the HPV RCT, V501-20 published by Giuliano et al. [12]. The 1945 males randomized to the Gardasil unit experienced a statistically significantly higher rate of all-type AE (63.86 %) versus AAHS adjuvants (58.15 %) (p < 0.001). In fact of the 7 publications reporting all-type adverse events, 5 found a significant difference between the two cohorts [7, 8, 12, 14, 16]. The remaining two articles reporting no difference were limited by a cohort size of less than 100 persons [11, 15]. The most common AE was injection-site reactions, such as pain, erythema, and induration. In the present literature review, all-type injection-site reactions were statistically significantly higher in the vaccine arm (77.43 %) than the control arm (67.70 %) (p < 0.001). However, true injection-site, hypersensitivity reactions occur infrequently, according a retrospective review of 380,000 doses of Gardasil administered to 12–26 year-old females in Victoria and South Australia [42]. In that study, only 35 females had suspected hypersensitivity reactions. Moreover, Kang et al. concluded that “only three of the 25 evaluated schoolgirls had probable hypersensitivity to the quadrivalent human papillomavirus vaccine [42].” Several authors contend that the causes of the general injection-site reactions, and the hypersensitivity experiences specifically, are not completely attributable to the antigenic components of the vaccine, but rather due in part to the aluminum additives [39, 42]. In the RCT by Reisinger et al. (Table 1), the placebo group was given saline injections, from which only half of participants experienced injection-site reactions [16]. By comparison, the frequency of injection-site reactions averages at 68.95 % in control arms with Al(OH)3 or AAHS and 77.43 % in the vaccinated arm, per the set literature review. Such a gradient effect suggests that the aluminum products contribute to the reactogenicity of the vaccine [39].

Systemic events did not differ in the vaccine division (35.28 %) versus the control division (36.14 %) (p = 0.223); furthermore, most reported symptoms were mild or moderate in intensity. Fatigue, headache, and pyrexia were most commonly documented throughout the follow up period. Delayed in onset, these experiences likely reflect the initial innate immunologic response followed by a sustained, adaptive response. Yoshikawa et al. did detect a statistically significant difference of all-type adverse events between the vaccine arm and control arm (p < 0.001) (Table 1) [14]. The most common AE was injection-site adverse event, among which pain was the most frequent symptom. Systemic AE were the next most common event, although no statistically significant difference was detected between the vaccine and control cohorts (p = 0.260). Greater than 90 % of those systemic AEs were of “moderate intensity,” without any specification.

Serious AE in the present study did not statistically significantly differ between the vaccine (0.15 %) and control (0.14 %) groups (p = 0.774) in the present literature review. Commensurate with our findings, Roumbout et al. reported no difference in serious AE in a systematic review of six HPV trials (Peto odds ratio 1.00; 95 % CI 0.87–1.14). Death between the two arms did not differ (Peto odds ratio 0.91; 95 % CI 0.39–2.14) [43]. In the aforementioned review by Roumbout et al. as well as the present review, motor vehicle accidents were the most common cause of death. No mortalities were associated with the vaccine.

Conclusion

Following PRISMA guidelines, the literature review rendered 13 randomized controlled trials comparing HPV vaccine to control. Of the 11,189 individuals in 7 publications reporting cumulative, all-type adverse events, the vaccinated group was statistically significantly higher than the control group, although the most common AE were injection-site reactions. On the other hand, systemic symptoms did not statistically significantly differ. The pregnancy/ perinatal outcomes rendered no statistically significant difference between the vaccine group and control group. Thus, the vaccinations are safe preventative measures for both males and females.

Abbreviations

- [Al(OH)3]:

-

Aluminum hydroxide

- AAHS:

-

Amorphous aluminum hydroxyphosphate sulfate

- AE:

-

Adverse events

- AS:

-

Adjuvant System

- FDA:

-

Food and Drug Administration

- FUTURE:

-

Females United to Unilaterally Reduce Endo/Ectocervical Disease

- HIV:

-

Human Immunodeficiency Virus

- HPV:

-

Human papilloma virus

- PRISMA:

-

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

- RCTs:

-

Randomized controlled trials

- VLP:

-

Virus-like particle

References

Dunne EF, Unger ER, Sternberg M, McQuillan G, Swan DC, Patel SS, et al. Prevalence of HPV infection among females in the United States. JAMA. 2007;297(8):813–9. doi:10.1001/jama.297.8.813.

Garland SM, Hernandez-Avila M, Wheeler CM, Perez G, Harper DM, Leodolter S, et al. Quadrivalent vaccine against human papillomavirus to prevent anogenital diseases. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(19):1928–43. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa061760.

Group FIS. Quadrivalent vaccine against human papillomavirus to prevent high-grade cervical lesions. N Engl J Med. 2007;356(19):1915–27. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa061741.

GlaxoSmithKline Vaccine HPVSG, Romanowski B, de Borba PC, Naud PS, Roteli-Martins CM, De Carvalho NS, et al. Sustained efficacy and immunogenicity of the human papillomavirus (HPV)-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted vaccine: analysis of a randomised placebo-controlled trial up to 6.4 years. Lancet. 2009;374(9706):1975–85. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61567-1.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, Group P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. Open Med. 2009;3(3):e123–30. PubMed PMID: 21603045, PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3090117.

Harper DM, Franco EL, Wheeler C, Ferris DG, Jenkins D, Schuind A, et al. Efficacy of a bivalent L1 virus-like particle vaccine in prevention of infection with human papillomavirus types 16 and 18 in young women: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2004;364(9447):1757–65. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17398-4.

Villa LL, Costa RL, Petta CA, Andrade RP, Ault KA, Giuliano AR, et al. Prophylactic quadrivalent human papillomavirus (types 6, 11, 16, and 18) L1 virus-like particle vaccine in young women: a randomised double-blind placebo-controlled multicentre phase II efficacy trial. Lancet Oncol. 2005;6(5):271–8. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(05)70101-7.

Munoz N, Manalastas Jr R, Pitisuttithum P, Tresukosol D, Monsonego J, Ault K, et al. Safety, immunogenicity, and efficacy of quadrivalent human papillomavirus (types 6, 11, 16, 18) recombinant vaccine in women aged 24-45 years: a randomised, double-blind trial. Lancet. 2009;373(9679):1949–57. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60691-7.

Bhatla N, Suri V, Basu P, Shastri S, Datta SK, Bi D, et al. Immunogenicity and safety of human papillomavirus-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted cervical cancer vaccine in healthy Indian women. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2010;36(1):123–32. doi:10.1111/j.1447-0756.2009.01167.x.

Ngan HY, Cheung AN, Tam KF, Chan KK, Tang HW, Bi D, et al. Human papillomavirus-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted cervical cancer vaccine: immunogenicity and safety in healthy Chinese women from Hong Kong. Hong Kong Med J. 2010;16(3):171–9.

Levin MJ, Moscicki AB, Song LY, Fenton T, Meyer 3rd WA, Read JS, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of a quadrivalent human papillomavirus (types 6, 11, 16, and 18) vaccine in HIV-infected children 7 to 12 years old. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2010;55(2):197–204. doi:10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181de8d26. PubMed PMID: 20574412, PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3033215.

Giuliano AR, Palefsky JM, Goldstone S, Moreira Jr ED, Penny ME, Aranda C, et al. Efficacy of quadrivalent HPV vaccine against HPV Infection and disease in males. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(5):401–11. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa0909537. PubMed PMID: 21288094, PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3495065.

Sow PS, Watson-Jones D, Kiviat N, Changalucha J, Mbaye KD, Brown J, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of human papillomavirus-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted vaccine: a randomized trial in 10-25-year-old HIV-Seronegative African girls and young women. J Infect Dis. 2013;207(11):1753–63. doi:10.1093/infdis/jis619. PubMed PMID: 23242542, PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3636781.

Yoshikawa H, Ebihara K, Tanaka Y, Noda K. Efficacy of quadrivalent human papillomavirus (types 6, 11, 16 and 18) vaccine (GARDASIL) in Japanese women aged 18-26 years. Cancer Sci. 2013;104(4):465–72. doi:10.1111/cas.12106.

Denny L, Hendricks B, Gordon C, Thomas F, Hezareh M, Dobbelaere K, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of the HPV-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted vaccine in HIV-positive women in South Africa: a partially-blind randomised placebo-controlled study. Vaccine. 2013;31(48):5745–53. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.09.032.

Reisinger KS, Block SL, Lazcano-Ponce E, Samakoses R, Esser MT, Erick J, et al. Safety and persistent immunogenicity of a quadrivalent human papillomavirus types 6, 11, 16, 18 L1 virus-like particle vaccine in preadolescents and adolescents: a randomized controlled trial. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2007;26(3):201–9.

Pedersen C, Breindahl M, Aggarwal N, Berglund J, Oroszlan G, Silfverdal SA, et al. Randomized trial: immunogenicity and safety of coadministered human papillomavirus-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted vaccine and combined hepatitis A and B vaccine in girls. J Adolesc Health. 2012;50(1):38–46. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.10.009.

Lehtinen M, Paavonen J, Wheeler CM, Jaisamrarn U, Garland SM, Castellsague X, et al. Overall efficacy of HPV-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted vaccine against grade 3 or greater cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: 4-year end-of-study analysis of the randomised, double-blind PATRICIA trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012;13(1):89–99. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70286-8.

Szarewski A, Poppe WA, Skinner SR, Wheeler CM, Paavonen J, Naud P, et al. Efficacy of the human papillomavirus (HPV)-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted vaccine in women aged 15–25 years with and without serological evidence of previous exposure to HPV-16/18. Int J Cancer. 2012;131(1):106–16. doi:10.1002/ijc.26362.

Schmeink CE, Bekkers RL, Josefsson A, Richardus JH, Berndtsson Blom K, David MP, et al. Co-administration of human papillomavirus-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted vaccine with hepatitis B vaccine: randomized study in healthy girls. Vaccine. 2011;29(49):9276–83. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.08.037.

Leroux-Roels G, Haelterman E, Maes C, Levy J, De Boever F, Licini L, et al. Randomized trial of the immunogenicity and safety of the Hepatitis B vaccine given in an accelerated schedule coadministered with the human papillomavirus type 16/18 AS04-adjuvanted cervical cancer vaccine. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2011;18(9):1510–8. doi:10.1128/CVI.00539-10. PubMed PMID: 21734063, PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3165228.

Kim YJ, Kim KT, Kim JH, Cha SD, Kim JW, Bae DS, et al. Vaccination with a human papillomavirus (HPV)-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted cervical cancer vaccine in Korean girls aged 10–14 years. J Korean Med Sci. 2010;25(8):1197–204. doi:10.3346/jkms.2010.25.8.1197. PubMed PMID: 20676333, PubMed Central PMCID: PMC2908791.

Konno R, Tamura S, Dobbelaere K, Yoshikawa H. Efficacy of human papillomavirus type 16/18 AS04-adjuvanted vaccine in Japanese women aged 20 to 25 years: final analysis of a phase 2 double-blind, randomized controlled trial. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2010;20(5):847–55. doi:10.1111/IGC.0b013e3181da2128.

Medina DM, Valencia A, de Velasquez A, Huang LM, Prymula R, Garcia-Sicilia J, et al. Safety and immunogenicity of the HPV-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted vaccine: a randomized, controlled trial in adolescent girls. J Adolesc Health. 2010;46(5):414–21. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.02.006.

Konno R, Tamura S, Dobbelaere K, Yoshikawa H. Efficacy of human papillomavirus 16/18 AS04-adjuvanted vaccine in Japanese women aged 20 to 25 years: interim analysis of a phase 2 double-blind, randomized, controlled trial. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2010;20(3):404–10. doi:10.1111/IGC.0b013e3181d373a5.

Wacholder S, Chen BE, Wilcox A, Macones G, Gonzalez P, Befano B, et al. Risk of miscarriage with bivalent vaccine against human papillomavirus (HPV) types 16 and 18: pooled analysis of two randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 2010;340:c712. doi:10.1136/bmj.c712. PubMed PMID: 20197322, PubMed Central PMCID: PMC2831171.

Paavonen J, Naud P, Salmeron J, Wheeler CM, Chow SN, Apter D, et al. Efficacy of human papillomavirus (HPV)-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted vaccine against cervical infection and precancer caused by oncogenic HPV types (PATRICIA): final analysis of a double-blind, randomised study in young women. Lancet. 2009;374(9686):301–14. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61248-4.

Konno R, Dobbelaere KO, Godeaux OO, Tamura S, Yoshikawa H. Immunogenicity, reactogenicity, and safety of human papillomavirus 16/18 AS04-adjuvanted vaccine in Japanese women: interim analysis of a phase II, double-blind, randomized controlled trial at month 7. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2009;19(5):905–11. doi:10.1111/IGC.0b013e3181a23c0e.

Paavonen J, Jenkins D, Bosch FX, Naud P, Salmeron J, Wheeler CM, et al. Efficacy of a prophylactic adjuvanted bivalent L1 virus-like-particle vaccine against infection with human papillomavirus types 16 and 18 in young women: an interim analysis of a phase III double-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2007;369(9580):2161–70. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60946-5.

Khatun S, Akram Hussain SM, Chowdhury S, Ferdous J, Hossain F, Begum SR, et al. Safety and immunogenicity profile of human papillomavirus-16/18 AS04 adjuvant cervical cancer vaccine: a randomized controlled trial in healthy adolescent girls of Bangladesh. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2012;42(1):36–41. doi:10.1093/jjco/hyr173. PubMed PMID: 22194637, PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3244935.

de Vos van Steenwijk PJ, van Poelgeest MI, Ramwadhdoebe TH, Lowik MJ, Berends-van der Meer DM, van der Minne CE, et al. The long-term immune response after HPV16 peptide vaccination in women with low-grade pre-malignant disorders of the uterine cervix: a placebo-controlled phase II study. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2014;63(2):147–60. doi:10.1007/s00262-013-1499-2.

Clark LR, Myers ER, Huh W, Joura EA, Paavonen J, Perez G, et al. Clinical trial experience with prophylactic human papillomavirus 6/11/16/18 vaccine in young black women. J Adolesc Health. 2013;52(3):322–9. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2012.07.003.

Palmroth J, Merikukka M, Paavonen J, Apter D, Eriksson T, Natunen K, et al. Occurrence of vaccine and non-vaccine human papillomavirus types in adolescent Finnish females 4 years post-vaccination. Int J Cancer. 2012;131(12):2832–8. doi:10.1002/ijc.27586.

Joura EA, Garland SM, Paavonen J, Ferris DG, Perez G, Ault KA, et al. Effect of the human papillomavirus (HPV) quadrivalent vaccine in a subgroup of women with cervical and vulvar disease: retrospective pooled analysis of trial data. BMJ. 2012;344:e1401. doi:10.1136/bmj.e1401. PubMed PMID: 22454089, PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3314184.

Roteli-Martins CM, Naud P, De Borba P, Teixeira JC, De Carvalho NS, Zahaf T, et al. Sustained immunogenicity and efficacy of the HPV-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted vaccine: up to 8.4 years of follow-up. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2012;8(3):390–7. doi:10.4161/hv.18865.

Palefsky JM, Giuliano AR, Goldstone S, Moreira Jr ED, Aranda C, Jessen H, et al. HPV vaccine against anal HPV infection and anal intraepithelial neoplasia. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(17):1576–85. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1010971.

Tay EH, Garland S, Tang G, Nolan T, Huang LM, Orloski L, et al. Clinical trial experience with prophylactic HPV 6/11/16/18 VLP vaccine in young women from the Asia-Pacific region. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2008;102(3):275–83. doi:10.1016/j.ijgo.2008.03.021.

Group FIS. Prophylactic efficacy of a quadrivalent human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine in women with virological evidence of HPV infection. J Infect Dis. 2007;196(10):1438–46. doi:10.1086/522864.

Moreira Jr ED, Palefsky JM, Giuliano AR, Goldstone S, Aranda C, Jessen H, et al. Safety and reactogenicity of a quadrivalent human papillomavirus (types 6, 11, 16, 18) L1 viral-like-particle vaccine in older adolescents and young adults. Hum Vaccin. 2011;7(7):768–75. doi:10.4161/hv.7.7.15579. PubMed PMID: 21712645, PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3219080.

Stern AM, Markel H. The history of vaccines and immunization: familiar patterns, new challenges. Health Aff (Millwood). 2005;24(3):611–21. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.24.3.611.

Jenner E. An inquiry into the causes and effects of the variolae vaccinae. London: Dawsons of Pall Mall; 1966.

Kang LW, Crawford N, Tang ML, Buttery J, Royle J, Gold M, et al. Hypersensitivity reactions to human papillomavirus vaccine in Australian schoolgirls: retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2008;337:a2642. doi:10.1136/bmj.a2642. PubMed PMID: 19050332, PubMed Central PMCID: PMC2769055.

Rambout L, Hopkins L, Hutton B, Fergusson D. Prophylactic vaccination against human papillomavirus infection and disease in women: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. CMAJ. 2007;177(5):469–79. doi:10.1503/cmaj.070948. PubMed PMID: 17671238, PubMed Central PMCID: PMC1950172.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

No sources of funding were involved in this research: the design of the study and collection, analysis, interpretation of data, or in writing the manuscript.

Availability of data and materials

The data supporting the findings in this manuscript can be obtained by e-mail the corresponding author, Ali Dabaja, MD.

Authors’ contributions

MM contributed to gathering the data and writing/ assembling the manuscript. AAD contributed to interpreting the data. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

This manuscript does not contain any individual person’s data in any form (including individual details, images or videos).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Macki, M., Dabaja, A. Literature review of vaccine-related adverse events reported from HPV vaccination in randomized controlled trials. Basic Clin. Androl. 26, 16 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12610-016-0042-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12610-016-0042-7