Abstract

Background

The parasitic disease known as the cystic echinococcosis (CE) is brought on by cysts made up of the larval forms (metacestodes) of Echinococcus tapeworms. In North Africa, it is greater in rural regions. This is unusual for a primary supravesical position.

Case presentation

We report a case of a 6-year-old boy who had a palpable abdominal mass with hypogastric abdominal pain.

A pelvic ultrasound examination demonstrated a voluminous intra-abdominal supravesical cystic formation with clear limits and regular contours of heterogeneous anechogenic echostructure and the presence of multiple hyperechoic septa separating the cubicles (daughter vesicles) in a honeycomb pattern. Computed tomography confirmed a cystic echinococcosis stage III of the pelvis.

After a laparotomy surgery with total cystectomy, the patient was discharged with prescribed albendazole 10 mg/kg/day. Cystic echinococcosis was established by histological analysis.

The aim is to demonstrate that from a literature search, we think this is the first case of cystic echinococcosis of the detrusor in children.

Conclusion

Primary pelvic cystic echinococcosis is uncommon and even less common among children. Cystic echinococcosis must be taken into account in the differential diagnosis when there is an abdominal mass, particularly in locations where it is prevalent.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Background

Based on international consensus on terminology in the field of echinococcosis, cystic echinococcosis (CE) is the most appropriate word assigned to the zoonotic parasitic infection previously called hydatid disease [1], which is endemic in many parts of the planet. Countries around the Mediterranean were the known endemic regions for cystic echinococcosis including Algeria [2]. This parasitic disease is mainly caused by metacestode of the tapeworm belonging to the Echinococcus granulosus sensu latu (E.g) complex, inhabiting the small intestine predominantly of dogs and other canines [3]. The incubation period may vary due to the whereabouts, the type, and the severity and ranges from 5 up to 20 years [4]. Humans are accidental hosts for metacestodes of Echinococcus granulosus (E.g) by coming into contact with contaminated plants, animals, or soil and by consuming food, water, and edible vegetables contaminated with the definitive host feces [4] and are known to play a role in parasite transmission. It may develop in almost any part of the human body through hematogenous and lymphatic dissemination. In adults, the cyst’s location is mostly hepatic, followed by pulmonary [5]. However, Echinococcosis in children most frequently affects the lung. Children's echinococcosis is hypothesized to spread quickly because of the very elastic and compressible tissue found in their lungs [6, 7].

This is reviewed to demonstrate that from a literature search, we think this is the first case of cystic echinococcosis of the detrusor in children; only a few cases in adults were reported in the literature [8, 9].

2 Case presentation

A 06-year-old boy presented to our pediatric surgery department’s emergency room with several episodes of vomiting, limping, and localized hypogastric abdominal pain. He lived near a farm in a rural area. On clinical examination, he expressed hypogastric pain and a tender palpable mass under the umbilicus; the rest of the clinical examination showed no significant findings.

A pelvic ultrasound examination was carried out with Doppler (Fig. 1) demonstrated a voluminous intra-abdominal supravesical cystic formation oval shape measuring (61 × 51 × 54 mm) with clear limits and regular contours of heterogeneous anechogenic echostructure and the presence of multiple hyperechoic septa separating the cubicles (daughter vesicles) in a honeycomb pattern.

The biological findings showed that the white blood cell count was 7190 cells/mm3, the hemoglobin level was 12.4 g/dl, and high monocytosis was 7.5%.

By using the indirect hemagglutination assay (IHA), the result of serum titers of 1/160 was positive for E. granulosus antibodies. However, the results of the Echinococcus serology were inconclusive, and the results being 1/160. Liver and kidney functions were within normal ranges.

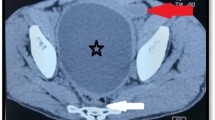

He was advised to undergo a computed tomography scan for further evaluation (Fig. 2), performed before and after the injection of contrast substance, which confirmed the ultrasound findings that revealed a large, fluid density lesion, right mediolateral intra-abdominal cystic lesion with hypogastric and periumbilical position, roughly oval in shape, well-defined, high-density wall, and various inner calcifications 64 × 63 mm in the transverse diameter extended over 61 mm in height, with multiple internal septations and daughter cysts evoking a cystic echinococcosis stage III of Gharbi. This lesion pushes the digestive structures forward and laterally. Inside and below present an intimate contact with the bladder wall. Posteriorly, it comes into contact with the primitive and right external iliac vessels.

The patient underwent exploratory laparoscopy converted to laparotomy. The first optical trocar n°10 was inserted trans-umbilically, and the second trocar n°5 was inserted on the right flank. The procedure helped identify a cystic formation in the pelvis that was particularly very adherent to the bladder and the abdominal wall, but there were issues with optics that forced us to stop the laparoscopy and convert to laparotomy. Anatomic layers were passed with a mini-median incision below the umbilicus. A well-limited calcified encapsulated cystic mass, about 10 cm in diameter long axis was immediately noticed. Very adherent to the bladder wall, the right ureter, the abdominal wall, and neighboring organs, as well the vascular axis (colic vessel) establishing that it was a pelvic cystic echinococcosis with a detrusor muscle starting point.

We then started the difficult process of releasing the cyst, which was incredibly challenging at the level of the bladder dome and resulted in a superficial rupture at the level of the detrusor muscle that was sutured in 2 layers using 5/0 threads. Finishing the laparotomy with total cystectomy of a non-opened cyst (Fig. 3A).

The piece was sent for histopathological study. Macroscopically, it is a 6 cm in diameter cystic structure. The cyst cavity is filled with translucent daughter cysts between 1 and 2 cm in size (Fig. 3B); the microscopic examination of the various fragments shows a cystic development with a proligerous layer lining an anhistic eosinophilic cuticular membrane as its wall. It has a fibrous tissue lining on its exterior face that has been changed by a mononuclear inflammatory infiltrate. Notable lack of scoleces (Fig. 4).

After surgery, the patient was discharged with prescribed albendazole 10 mg/kg/day for 3 months.

At the 12-month follow-up, the patient was without symptom; ultrasound examination was normal and demonstrated no evidence of recurrent hydatidosis.

3 Discussion

Cystic echinococcosis (CE) is a cosmopolitan parasitic disease that is most commonly caused by the larval stage of Echinococcus granulosus. It is still a considerable health problem in the world [10] More than 1 million people are in danger of contracting echinococcosis at any given moment, according to the studies. These cestodes have a worldwide distribution; however, the frequency is significantly higher in developing countries including North Africa [2]

CE can vary in location. The most common sites of involvement for adults are the liver (59–75%), followed in frequency by the lung (27%), kidney (3%), bone (1–4%), and brain (1–2%). As in children, the lung was the primary localization of cysts (59%) followed by the liver (35%) [11]. According to our presented case here, it is quite uncommon for detrusor cyst to be primary and not impact the liver or the lungs. [12], and that possibility goes even lower when it concerns children. From a literature search, we think this is the first case of cystic echinococcosis of the detrusor in children.

The clinical presentation might be asymptomatic for a long period of the incubation and is usually late diagnosed. Once symptomatic, it is often accompanied by urinary manifestations (pollakiuria, urinary retention) [13] or external pressure affecting the adjacent pelvic organs.

For the diagnosis, a physical examination is insufficient. Ultrasonography is the preferred first-line imaging. Diagnostic accuracy has significantly increased as a result of radiological imaging such as ultrasound and computed tomography (CT) scans, enabling doctors to establish the precise diagnosis.

Surgery is the gold standard therapy for CE, either by laparoscopic surgery or by doing a partial cystectomy [14]. In our case, the classification of the cyst was Gharbi type 3, so the indication for a partial, subtotal, or total cystectomy according to the Approach, Opening, Resection and Completeness (AORC) [1]

As for the cystic echinococcosis medical antiparasitic treatment, it aims to get rid of the parasite. Mortality reduction and recurrence prevention are crucial. Due to its excellent gastrointestinal absorption and high bioavailability, albendazole is the chosen medicine. The typical prescription for albendazole is 15 mg/kg daily divided into two doses without the monthly interruptions [15]. Between 60 and 90% of patients who get albendazole for 4–6 months respond to the medication; nevertheless, 30% do not respond to the treatment, and 10%-20% of patients have recurrence [16].

Percutaneous aspiration, injection, and reaspiration (PAIR) of the cyst is another treatment option. It is typically used to treat liver cysts or cysts in other organs and involves performing a percutaneous puncture under imaging guidance, aspirating some of the cyst's contents, injecting protoscolicidal agent (e.g., 95% ethanol or hypertonic saline) for about 15 min, and then aspirating the cyst's contents again [17].

PAIR is performed on patients for whom surgery is not appropriate for any reason or if they want not to undergo surgery. For single or many cysts in the liver, abdomen, spleen, kidney, and bones, PAIR is helpful.

Several local complications might arise (for example, fistulation into hollow viscera such as the bladder, peritoneal seeding, and abdominal wall invasion). Furthermore, secondary involvement owing to hematogenous dissemination can occur in virtually any anatomic region (lung, kidney, spleen, bone, and brain) [18]. However, the most dangerous one is the anaphylactic shock after the rupture of the cyst due to trauma, mortality was also reported [19]. Although it is a relatively uncommon occurrence, the traumatic rupture of a cyst in a blood artery should be kept in mind in the setting of anaphylactic shock, particularly in endemic areas. Laparoscopic surgery could be advised for such complications and showed promising results [20].

4 Conclusions

Although it is an uncommon condition, the differential diagnosis of cystic masses in the pelvis, particularly in endemic regions, must take the primary cystic echinococcosis of the bladder into account. This rare location in the detrusor can manifest in various nonspecific ways. Both ultrasound and computed tomography scan are top-notch imaging techniques for finding cystic echinococcosis. A laparotomy or laparoscopic procedure can be used to carefully and completely remove the pelvic cystic echinococcosis as the preferred course of therapy. This is in conjunction with medical treatment for prophylaxis.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Abbreviations

- CE:

-

Cystic echinococcosis

- E.g:

-

E. granulosus

- IHA:

-

Indirect hemagglutination

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- AORC:

-

Approach, opening, resection, and completeness

- PAIR:

-

Percutaneous aspiration, injection, and reaspiration

References

Vuitton DA, McManus DP, Rogan MT, Romig T, Gottstein B, Naidich A, Tuxun T, Wen H, Menezes da Silva A, and the World Association of Echinococcosis (2020) International consensus on terminology to be used in the field of echinococcosis. Parasite 27:41

Sadjjadi SM (2006) Present situation of echinococcosis in the Middle East and Arabic North Africa. Parasitol Int. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.PARINT.2005.11.030

Kern P, Menezes da Silva A, Akhan O, Müllhaupt B, Vizcaychipi KA, Budke C et al (2017) The Echinococcoses: diagnosis, clinical management and burden of disease. Adv Parasitol 96(259):369. https://doi.org/10.1016/BS.APAR.2016.09.006

Markell and Voge’s Medical Parasitology - Elsevier eBook on VitalSource, 9th Edition - 9781437719826 n.d. https://evolve.elsevier.com/cs/product/9781437719826?role=student&CT=DZ (accessed October 8, 2022).

Polat P, Kantarci M, Alper F, Suma S, Koruyucu MB, Okur A (2003) Hydatid disease from head to toe. Radiographics 23:475–494. https://doi.org/10.1148/rg.232025704

Hafsa C, Belguith M, Golli M, Rachdi H, Kriaa S, Elamri A et al (2005) Imaging of pulmonary hydatid cyst in children. J Radiol 86:405–410. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0221-0363(05)81372-1

Haif A, Achouri D, Bougharnout H, Chahmana A, Bouchareb F, Bendecheche B et al (2022) Coexistence of pulmonary hydatid cyst and tuberculosis in a child: a case report. Ann Pediat Surg. https://doi.org/10.1186/s43159-022-00198-9

Singla V, Suhani S, Bhattacharjee HK, Goyal A, Parshad R (2021) Solitary pelvic primary intraperitoneal hydatid managed with a minimal access approach: a case report. Asian J Endosc Surg 14:561–564. https://doi.org/10.1111/ASES.12867

Arif SH, Mohammed AA (2018) Primary hydatid cyst of the urinary bladder. BMJ Case Rep. https://doi.org/10.1136/BCR-2018-226341

Lewall DB (1998) Hydatid disease: biology, pathology, imaging and classification. Clin Radiol 53:863–874. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0009-9260(98)80212-2

Oudni-M’Rad M, M’Rad S, Gorcii M, Mekki M, Belguith M, Harrabi I et al (2007) Cystic echinococcosis in children in Tunisia: fertility and case distribution of hydatid cysts. Bull Soc Pathol Exot 100:10–3

Muni S, Kumari N, Pankaj D, Kumar A, Pintu DK (2017) Hydatid cyst in urine: a case report. Int J Sci Study 5:257–259

Dua B, Sharma R, Tiwari T, Goyal S (2022) Primary pelvic hydatid cyst causing acute urinary retention. BMJ Case Rep. https://doi.org/10.1136/bcr-2022-250627

Subramaniam B, Abrol N, Kumar R (2013) Laparoscopic Palanivelu-hydatid-system aided management of retrovesical hydatid cyst. Indian J Urol 29:59. https://doi.org/10.4103/0970-1591.109987

Brunetti E, Kern P, Vuitton DA (2010) Expert consensus for the diagnosis and treatment of cystic and alveolar echinococcosis in humans. Acta Trop 114:1–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.ACTATROPICA.2009.11.001

Saimot AG (2001) Medical treatment of liver hydatidosis. World J Surg 25(1):15–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/S002680020003

Moro P, Schantz PM (2009) Echinococcosis: a review. Int J Infect Dis 13:125–133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijid.2008.03.037

Pedrosa I, Saíz A, Arrazola J, Ferreirós J, Pedrosa CS (2000) Hydatid disease: radiologic and pathologic features and complications. Radiographics 20:795–817. https://doi.org/10.1148/RADIOGRAPHICS.20.3.G00MA06795

Beyrouti MI, Beyrouti R, Abbes I, Kharrat M, Ben AM, Frikha F et al (2004) Acute rupture of hydatid cysts in the peritoneum: 17 cases. Presse Med 33:378–384. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0755-4982(04)98600-9

Assia H (2022) Laparoscopic management of anaphylactic shock following abdominal trauma revealing intravascular rupture of cystic echinococcosis (A case report and brief literature review) In: Issues and developments in medicine and medical research. Vol. 5, Book Publisher International (a part of SCIENCEDOMAIN International), pp 29–34

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AH and DA analyzed and interpreted the patient data regarding the cystic echinococcosis and carried out the surgery. SO performed the histological examination of the cyst, MYM acquired and collected the imaging and was a major contributor in writing the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Informed written consent was obtained from the parents of the patient for publication of this report and the accompanying images.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Haif, A., Achouri, D., Merouani, M.Y. et al. Echinococcosis of the detrusor: report of the first pediatric case. Afr J Urol 29, 22 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12301-023-00355-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12301-023-00355-5