Abstract

Background

Primary signet-ring cell carcinoma (SRCC) of the prostate is a rare and aggressive subtype of prostate adenocarcinoma with a poor prognosis, with only approximately 60 cases reported worldwide.

Case presentation

A 62-year-old man presented with acute urinary retention and hematuria, after a year’s history of lower urinary tract symptoms. Digital rectal examination revealed an irregular and hard prostate. Flexible cystoscopy showed bladder base infiltration by the enlarged prostate obscuring both ureteric orifices, necessitating nephrostomy and subsequent bilateral antegrade stenting to relieve the obstruction and improve his renal function. Transrectal ultrasonography biopsy of the prostate was performed revealing histological features of SRCC. Due to its rarity, there is currently no standardized treatment approach and it is often similarly treated according to the traditional management of prostate adenocarcinoma.

Conclusions

SRCC of the prostate is a rare and aggressive subtype of acinar adenocarcinoma with no established guidelines. Histological criteria for SRCC of the prostate are highly variable in the available literature. It is important to differentiate between the primary and metastatic SRCC of the prostate as both are managed differently. However, the overall prognosis remains poor in general.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Background

Prostate cancer is the second most prevalent malignancy in men worldwide, with 1,276,106 new cases, (7.1% of all cancers) and caused 358,989 deaths (3.8% of all deaths caused by cancer in men) in 2018 [1]. Locally in Malaysia, prostate cancer is the 6th most frequent malignancy in 2018 with a total of 1807 cases reported (4.1%), and the 13th most frequent cause of cancer death with a total of 789 deaths (3%) [2]. The incidence trend increases at the age of 55 years and most were diagnosed after the age of 65 years [2].

The histological variants of acinar adenocarcinoma of the prostate which includes signet ring cell adenocarcinoma (SRCC) are updated in 2016 WHO classification. These variants are clinically important due to difficult diagnoses and prognostic differences compared with typical acinar adenocarcinoma [3]. SRCC is characterized by an intracytoplasmic vacuole compressing the nucleus into a crescent shape at the cellular level. SRCC is commonly found in the stomach and colon but it can also be found in the pancreas, breast, thyroid, bladder, and prostate [4]. Establishing a diagnosis of primary SRCC of the prostate requires histopathological examination and specialized staining of the prostate tumor tissue, and exclusion of other possible primary sites mainly in the gastrointestinal and female genitourinary tract via computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen, and gastrointestinal endoscopy. We describe a 62-year-old man with primary SRCC of the prostate and discuss its treatment strategy.

2 Case presentation

A 62-year-old man presented with acute urinary retention and hematuria, which was preceded by a year’s history of lower urinary tract symptoms namely weak flow, nocturia, and frequency. He was well initially with no family history of malignancy. Digital rectal examination revealed an irregular and hard prostate. He was catheterized and subsequent ultrasound of the kidney, ureter, and bladder showed findings of bladder outlet obstruction from an enlarged prostate. Flexible cystoscopy showed bladder base infiltration by the enlarged prostate obscuring both ureteric orifices, necessitating nephrostomy and subsequent bilateral antegrade stenting to relieve the obstruction and improve his renal function. His prostate-specific antigen (PSA) was only 1.8 ng/mL (normal: < 4).

A 12-core transrectal ultrasonography (TRUS) biopsy of the prostate was performed revealing histological features of SRCC. All tissue cores showed tumor cells infiltration by malignant cells clusters of signet ring morphology with the background of abundant extracellular mucin (Figs. 1, 2). Some of the malignant cells exhibited stromal infiltration among the residual benign prostatic glands. Adipose tissue involvement and perineural invasion were seen. No lymphovascular invasions were found. Immunohistochemical staining was negative for AE1/AE3, PSA, CK7, and GATA3 but was positive for CK20 and CDX2.

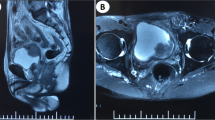

A CT of the thorax, abdomen, and pelvis was performed with the only finding of a heterogeneously enlarged locally advanced prostate carcinoma with involvement of the seminal vesicles (Figs. 3, 4). The prostate volume was 147 gm from CT scan. An esophagogastroduodenoscopy and colonoscopy were also performed and showed no abnormalities. The patient was planned for a magnetic resonance imaging and positron emission tomography for prostatic specific membrane antigen scan for cancer staging but unfortunately defaulted treatment due to personal reasons. Upon rigorous patient tracing, he was found to have passed away 4 months after diagnosis due to community-acquired pneumonia, before the imaging can be done.

3 Discussion

The patient was diagnosed at the age of 62-year-old, coherent with the reported median age for prostatic SRCC of around 68 years, with a range of 50–85 years [4, 8]. At the time of diagnosis, 75% of patients were seen to have a locally advanced or metastatic disease as per our patient who had a locally advanced T-stage for the prostate even though he had no metastases [4, 5]. Some studies stated that signet ring cells must constitute at least 20–25% of the tumor to be able to have a diagnosis of primary prostatic SRCC, although other studies stated that a certain ratio of cells was not needed for diagnosis [5]. Either way in our patient, all 12 cores of the TRUS biopsy demonstrated this malignancy which strongly suggests a prostatic SRCC in either school of thought.

Since the gastrointestinal tract harbors more common locations for signet ring cells, many tests especially various immunohistochemistry focus on differentiating a primary SRCC from one located in the gastrointestinal tract. The main diagnostic issue in this patient is in the immunohistochemistry aspect which showed a negative PSA staining, as primary prostatic SRCC cases are 87% positive for PSA/PSAP staining [4]. However, a study by Fujita et al. showed that 3 out of the 37 (8%) of patients with primary SRCC of the prostate did not stain positive for PSA [5]. PSA has also been demonstrated to be a prostate tissue-specific marker, but its reactivity may be lost in a significant number of high-grade, poorly differentiated, and metastatic prostatic adenocarcinoma [3, 6]. Clearly, it is crucial to differentiate between gastrointestinal and prostate origin as the treatment modalities vary remarkably. In metastatic gastrointestinal primary tumor, additional intervention would be required especially bowel resection, defunctioning, and/or stenting.

The intestinal marker CDX2, which was positive in this patient, has also recently been found to stain a small percentage of primary prostate adenocarcinomas and can be positive in 30% of SRCC. GATA3, which has been found negative in this patient, is a transcription factor important in the reliable differentiation of breast epithelium, urothelium, and subsets of T-lymphocyte [6, 7]. Another study done by Chang et al. showed that GATA3 is highly specific when differentiating high-grade urothelial carcinoma from high-grade prostatic adenocarcinoma. Eighty percent of the cases of urothelial carcinoma examined were GATA3 positive and all 38 high-grade prostatic adenocarcinomas in the study were GATA3 negative [8]. In addition, certain immunohistochemical markers namely estrogen receptor-beta and Ki67 are reliable prognostic markers in prostate adenocarcinoma [9].

Metastatic SRCC primarily from the gastrointestinal tracts and the urinary bladder must be ruled out by CT scan, cystoscopy, colonoscopy, and upper gastric tract endoscopy [5]. As in our case, in view of negative PSA stain from TRUS biopsy, metastatic SRCC needs to be ruled out. However, positron emission tomography which will be helpful to look for occult primary cancer could not be performed. In view of the histological findings, immunohistochemical study, and negative systemic examination for other possible primary sites, we concluded that it was a case of primary SRCC of the prostate.

Being a primary SRCC, there is no single treatment modality is ideal, however, an aggressive multimodal treatment paradigm should be considered. This includes an early hormonal treatment and aggressive surgical resection as well as adjuvant radiation therapy. Despite that, studies have shown an overall poor prognosis and survival even with aggressive therapy with a combination of all available modalities, with Fujita et al. showing a 5-year survival rate of only 11.7% while Warner et al. showed an average survival time of 29 months [4, 5]. In addition, stromogenic cancers and patterns with extravasated mucin have the worst outcome amongst Gleason 5 prostate cancers [10]. This is also unfortunately true for our patient who passed away 4 months before any treatment could be initiated.

4 Conclusions

SRCC of the prostate is a rare and aggressive subtype of acinar adenocarcinoma with no established guidelines. Histological criteria for SRCC of the prostate are highly variable in the available literature. It is important to differentiate between the primary and metastatic SRCC of the prostate as both are managed differently. However, the overall prognosis remains poor in general.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- PSA:

-

Prostate-specific antigen

- SRCC:

-

Signet ring cell adenocarcinoma

- TRUS:

-

Transrectal ultrasonography

References

Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A (2018) Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin 68(6):394–424

Azizah AM, Hashimah B, Nirmal K, Siti Zubaidah AR, Puteri NA, Nabihah A, et al. (2019) Malaysian National Cancer Registry Report 2012–2016. National Cancer Registry, June

Inamura K (2018) Prostatic cancers: understanding their molecular pathology and the 2016 WHO classification. Oncotarget 9(18):14723–14737

Warner JN, Nakamura LY, Pacelli A, Humphreys MR, Castle EP (2010) Primary signet ring cell carcinoma of the prostate. Mayo Clin Proc 85(12):1130–1136

Fujita K, Sugao H, Gotoh T, Yokomizo S, Itoh Y (2004) Primary signet ring cell carcinoma of the prostate: report and review of 42 cases. Int J Urol 11(3):178–181

Guerrieri C, Jobbagy Z, Hudacko R (2019) Expression of CDX2 in metastatic prostate cancer. Pathologica 111(3):105–107

Leite KR, Mitteldorf CA, Srougi M, Dall’oglio MF, Antunes AA, Pontes J Jr et al (2008) Cdx2, cytokeratin 20, thyroid transcription factor 1, and prostate-specific antigen expression in unusual subtypes of prostate cancer. Ann Diagn Pathol 12(4):260–266

Chang A, Amin A, Gabrielson E, Illei P, Roden RB, Sharma R et al (2012) Utility of GATA3 immunohistochemistry in differentiating urothelial carcinoma from prostate adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinomas of the uterine cervix, anus, and lung. Am J Surg Pathol 36(10):1472–1476

Azizan N, Hayati F, Tizen NMS, Farouk WI, Masir N (2018) Role of co-expression of estrogen receptor beta and Ki67 in prostate adenocarcinoma. Investig Clin Urol 59(4):232–237

McKenney JK, Wei W, Hawley S, Auman H, Newcomb LF, Boyer HD et al (2016) Histologic grading of prostatic adenocarcinoma can be further optimized: analysis of the relative prognostic strength of individual architectural patterns in 1275 patients from the Canary retrospective cohort. Am J Surg Pathol 40(11):1439–1456

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge those who have been directly or indirectly involved in the management of this patient throughout his hospitalization and discharge.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

SKS and MFMS wrote the initial manuscript. MFMS performed the literature review. SAMZ provided the study material. KAMG supervised the manuscript writing. NA provided the description of the histologic figures. FH revised the manuscript and became the corresponding author. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Ethical approval was not required as this is a case report. Informed written consent to participate was provided by all participants.

Consent for publication

The written consent for publication was obtained the patient and it is available upon request.

Competing interests

The authors declare they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Sidhu, S., Mohd Sharin, M., Mohd Ghani, K. et al. Primary prostatic signet ring cell carcinoma in elderly with obstructive uropathy: a case report. Afr J Urol 28, 16 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12301-022-00283-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12301-022-00283-w