Abstract

Background

Chloroplast genome variations have been detected, despite its overall conserved structure, which has been valuable for plant population genetics and evolutionary studies. Here, we described chloroplast variation architecture of 383 rice accessions from diverse regions and different ecotypes, in order to mine the rice chloroplast genome variation architecture and phylogenetic.

Results

A total of 3677 variations across the chloroplast genome were identified with an average density of 27.33 per kb, in which wild rice showing a higher variation density than cultivated groups. Chloroplast genome nucleotide diversity investigation indicated a high degree of diversity in wild rice than in cultivated rice. Genetic distance estimation revealed that African rice showed a low level of breeding and connectivity with the Asian rice, suggesting the big distinction of them. Population structure and principal component analysis revealed the existence of clear clustering of African and Asian rice, as well as the indica and japonica in Asian cultivated rice. Phylogenetic analysis based on maximum likelihood and Bayesian inference methods and the population splits test suggested and supported the independent origins of indica and japonica within Asian cultivated rice. In addition, the African cultivated rice was thought to be domesticated differently from Asian cultivated rice.

Conclusions

The chloroplast genome variation architecture in Asian and African rice are different, as well as within Asian or African rice. Wild rice and cultivated rice also have distinct nucleotide diversity or genetic distance. In chloroplast level, the independent origins of indica and japonica within Asian cultivated rice were suggested and the African cultivated rice was thought to be domesticated differently from Asian cultivated rice. These results will provide more candidate evidence for the further rice chloroplast genomic and evolution studies.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The chloroplast is maternally inherited in most angiosperms and possesses its own genome encoding many chloroplast-specific components (Hagemann 2010; Palmer et al. 1988; Sugiura 1989). The chloroplast has a circular genome, ranging in size from 39.4 to 200.8 kb among photosynthetic plant species (Kohler et al. 1997; Turmel et al. 1999). More than 800 eukaryotic viridiplantae chloroplast genomes have been described to date (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genomes/GenomesGroup.cgi?taxid=2759&opt=plastid). The chloroplast genome sequence of rice Nipponbare (O. sativa L. ssp. japonica) was reported to have a length of 134,525 bp (Hiratsuka et al. 1989). Chloroplasts contain both highly conserved genes fundamental to plant life and more variable regions, which have been informative over broad time scales. Comparative studies of the genomic architecture showed that the order of genes and the contents of essential genes are highly conserved among most chloroplast genomes (De Las Rivas et al. 2002; Kato et al. 2000). Nevertheless, variations among different and closely related genomes have occurred during evolution (Provan et al. 1997; Tang et al. 2004).

The availability of rice nuclear (Goff et al. 2002; Yu et al. 2002) and chloroplast (Hiratsuka et al. 1989) reference genomes has enabled detailed studies of the origin, domestication, and phylogenetic relationships within this group. In particular, whole chloroplast genome analysis provides high-resolution plant phylogenies (Parks et al. 2009). Due to the high level of conservation, analysis of the chloroplast genome has become a valuable tool for plant phylogenetic studies (Waters et al. 2012; Yang et al. 2013). Previously, only a few chloroplast markers have been applied in studies of plant diversity and evolution (Ishii et al. 2001; King and Ferris 2000; Schroeder et al. 2011; Soejima and Wen 2006). From the conventional sequencing of plant chloroplast genomes to next-generation sequencing (NGS), it has become increasingly feasible to investigate the entire genome of the chloroplast, rather than targeting individual regions (McPherson et al. 2013; Nock et al. 2011; Straub et al. 2012). Whole chloroplast genome sequencing for phylogenetic analysis without prior isolation or amplification is now relatively straightforward for plant species (Nock et al. 2011). However, the chloroplast genome only represents the maternal evolutionary history. In addition, it also cannot be fully applied to rapidly diverging taxa, as the chloroplast has a slow rate of evolution (Moore et al. 2010; Parks et al. 2009). Therefore, chloroplast-based evolutionary studies must sometimes be complemented by nuclear genomic information.

Asian cultivated rice (O. sativa L.) is generally considered to have been domesticated from Oryza rufipogon several thousands of years ago (Cheng et al. 2003; Huang et al. 2012; Khush 1997; Oka 1988). However, there has been some debate regarding the origin of cultivated rice over the past several years, which centered on whether the two major rice cultivars, O. sativa L. ssp. indica and japonica, were derived from a single ancestor or were domesticated independently at different locations (Jin et al. 2008; Kawakami et al. 2007; Li et al. 2006; Molina et al. 2011; Zhang et al. 2009; Zhu et al. 2011; Huang et al. 2012; Xu et al. 2012; Zhu and Ge 2005). While, African cultivated rice (O. glaberrima), which was thought to be domesticated from the wild progenitor O. barthii ~3000 years ago, had been demonstrated to be domesticated in a single region along the Niger river with independent and distinct process in regard to Asian cultivated rice (Wang et al. 2014). A closer evolutionary relationship between indica and aus strains were observed using both nuclear and chloroplast genome data, as well as among the tropical japonica, temperate japonica, and aromatic groups (Garris et al. 2005). The indica subpopulation was shown to contain the highest degree of chloroplast diversity (Garris et al. 2005). Kim et al. (2014) evaluated 67 improved varieties and 13 landraces from the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK) at both nuclear and chloroplast levels, and they found a temperate japonica subgroup that was less diverse than the indica ancestor group at the nuclear level but more diverse at the chloroplast level (Kim et al. 2014). Whole chloroplast genome phylogenetic analysis revealed that the Oryza nivara is closed to O. sativa L. spp. indica and the O. sativa L. spp. japonica is closed to Oryza rufipogon in Asian cultivated and wild rice (Brozynska et al. 2014) and the African rice (Oryza glaberrima and Oryza barthii) were cluster together but in separate group with the Asian rice (Wambugu et al. 2015). Our previous studies indicated that the use of chloroplast genome variation to study diversity, population genetics, and phylogenetic analysis was quite convincing and also supported some previous outcomes (Tong et al. 2015). Despite these chloroplast-related studies, a large number of accessions must be applied to extend these studies from limited collections and specific varieties. In addition to rice, chloroplast genome-dependent phylogenetic analyses have also been performed in apple, tangerine, and other species. (Nikiforova et al. 2013; Carbonell-Caballero et al. 2015).

In the present study, a collection of 383 rice accessions with diverse ecotypes, including Asian cultivated and wild rice (O. sativa L. spp. indica and japonica, Oryza rufipogon, Oryza nivara) and African cultivated and wild rice (Oryza glaberrima, Oryza barthii) were selected to investigate the variation, diversity, and phylogenetic of rice chloroplast genome. The chloroplast genome of O. rufipogon [Genbank: NC_017835], which is thought to be the immediate ancestral progenitor of cultivated rice, was chosen as the reference. Chloroplast variations in the collection were mined and subjected to comparative analysis among different groups. Diversity, population structure, and principal component analysis were also performed in the current collection. Phylogenetic analysis that conducted using the maximum likelihood (ML) and Bayesian inference (BI) methods and population splits evaluation were investigated, which could provide evidence to illustrate the phylogenetic relationships among rice subgroups, with a focus on Asian cultivated rice, as well as African rice (Oryza glaberrima and Oryza barthii). This report provides a further case study for the rice chloroplast genome, and the data generated here could be applied to further analyses of rice chloroplast evolution and genetics.

Results

Re-Sequencing and Variation Architecture Across the Chloroplast Genome

In this study, we re-sequenced 295 accessions of Asian cultivated rice with a high mean coverage (~7.34×), generating ~920Gbp raw sequence base with ~9.18 billion reads. After removing the low quality bases, a total of ~8.89 billion clean reads (with a clean read rate of 96.96 %) and ~860Gbp clean bases (with a clean base rate of 93.73 %) were obtained (Additional file 1: Table S1). Then this data was carried out for rice chloroplast genome variations detecting and phylogenetic analysis together with other 88 rice accessions.

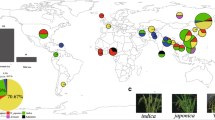

Variations in 383 rice accessions, including 335 Asian cultivated rice (O. sativa L.), 10 Asian wild rice (O. rufipogon, O. nivara), 19 African cultivated rice (Oryza glaberrima), and 19 African wild rice (Oryza barthii), were characterized based on whole-genome resequencing data using the chloroplast genome of O. rufipogon as a reference. A total of 3677 variations, including 3592 SNPs and 85 indels (insertions/deletions), were identified in the whole collection (Table 1). A variation density of 27.33 per 1kb were observed through the total SNPs/indels. However, after excluding missing genotypes with MAF (Minor Allele Frequency) ≥ 0.01, high-quality (HQ) variations were dramatically decreased to 242, including 227 SNPs (93.8 % of the total HQ variations) and 15 indels (6.2 % of the total HQ variations) with a variation density of 1.8 per 1 kb (Table 1). The overall variations across the genome and groups specific variations were also extracted, suggesting that the African wild rice hold about 82.9 % of the total variations on its own (Fig. 1, Table 1). What’s more, the distribution of the variations across the chloroplast genome is uneven (Fig. 1). Except the African wild rice, which harbored 2982 HQ variations (97.8 % of all variations), the Asian wild rice possessed the most number of HQ variations, even with only 10 accessions. Interestingly, a greatest abundance of variations in the African wild rice were observed both in all and HQ variations among all of the groups, however, the African cultivated rice had minimal variations.

Overall distribution of variations (SNPs and indels) across the chloroplast genome. Variations of all 383 accessions and different groups were identified based on the chloroplast reference genome of Oryza rufipogon. Circular map showing the chloroplast genome structure. The unit of the outer distance is kb. “Genes” indicating the genes (including genes, tRNA and rRNA) with their locations on the reference (O. rufipogon) genome. Each colored line indicating one variation. ASW: Asian wild rice, ASC: Asian cultivated rice, AFW: African wild rice, AFC: African cultivated rice. The numbers in the brackets of middle table indicated the number of accessions

After determination of the location of variations across the genome, 2156 SNPs/indels were found within the genic region scattered over 87 genes in whole variations, including those encoding tRNAs and rRNAs (Table 1, Additional file 2: Table S2). Only 141 variations were retained by HQ selection in the genic region, involved 27 genes. In the four different groups, maximum variations in African wild rice were found both in all and HQ variations, as expected, which including 86 and 81 genes, respectively. In HQ variations, the Asian wild rice held the most number of genic variations and involved genes except the African wild rice.

Different allele types were also investigated, which indicated that T/C and A/T have the most number in all variations, while A/G and C/T are the major types in HQ variations. The overall Ts/Tv (Transition/Transversion) ratio in chloroplast genome of whole collection was 0.7328, which indicates that the mutations within the same type of nucleotide were less than those from a pyrimidine to a purine or vice versa (Additional file 3: Figure S1). In the four groups, the Asian wild rice holds the highest Ts/Tv ratio (1.047), while the African wild rice holds the lowest (0.7093).

Genetic Diversity Evaluation of Rice Chloroplast Genome

The nucleotide diversity (pi) of the whole collection and different groups (Asian cultivated and wild rice, African cultivated and wild rice) was calculated with a mean pi of 0.000918 in whole collection. While among the subgroups, the African wild rice has the highest diversity (0.001959), and the African cultivated rice has the lowest (0.000548) (Fig. 2a, b, Additional file 4: Table S3). The Asian wild rice also holds a high pi (0.001665), and the Asian cultivated rice has the similar pi with whole collection (0.000987).

Chloroplast genome nucleotide diversity, genetic distance (Fst), and Tajima’s D test. a Nucleotide diversity (pi) and Fst value of four groups. The four circle indicated four groups and the circle size indicated the pi value. The Fst value between each two groups were represented by the distance between them. b, c Average pi and Tajima’s D value of the whole collection and each group. d Tajima’s D test of the overall chloroplast genome in 1kb bins. The sorted values were plotted in each groups. ASW: Asian wild rice, ASC: Asian cultivated rice, AFW: African wild rice, AFC: African cultivated rice

A long genetic distance (Fst) between Asian rice and African rice was observed (~0.43), which indicates the low levels of breeding and low connectivity between them (Fig. 2a). The African cultivated rice (O. glaberrima) has very high breeding level with the African wild rice (Oryza barthii). These results may suggest and support the distinct domestication between African and Asian rice. Tajima’s D value of the chloroplast genome was also examined for detection of balancing selection (Fig. 2c, Additional file 5: Table S4). The negative value indicated population size expansion and/or purifying selection, while a positive value indicated a decrease in population size and/or balancing selection. Values closer to 0 indicate less evidence for the occurrence of selection. According to the distribution (Fig. 2d), Tajima’s D value of all groups showed a location fluctuation in 1kb bins with positive, negative value and also 0. Excepting the African wild rice and whole collection, which showing more negative positions, other groups showing a relative even distribution of positive, negative and 0. The mean Tajima’s D value of whole collection and different groups was shown in Fig. 2c, the whole collection (because of diverse rice accessions) and African wild rice showing a relative high divergence. While closer Tajima’s D value to 0 indicated rare selection in the chloroplast genome.

Population Structure and Principal Component Analysis Based on Chloroplast Genome

The population structure of the whole collection was investigated based on the HQ variations using SRUCTURE, which estimates individual ancestry and admixture proportions assuming K populations. With increasing K (number of populations) values from 1 to 10 with 10 iterations each, we analyzed the population structure for each K value (Fig. 3a, from K = 2 to 4). We distinguished the major substructure groups using an optimal K value of 4 (highest ΔK, Additional file 6: Figure S2a). All the collected accessions formed four subpopulations, denoted as indica type, japonica type, Admixture, and African rice (wild and cultivated). In addition, a validation of population structure was conducted using ADMIXTURE from K = 1 to 10. With a cross-validation procedure, a good K value of 8 was adopted, which exhibited a lowest cross-validation error in all K values (Additional file 6: Figure S2b). The population structure form K = 4 to 8 was illustrated (Results in K = 2 and 3 were almost same using SREUCTURE and ADMIXTURE), which clustered the population into four subgroups (African cultivated and wild, Asian wild, and Asian cultivated with indica and japonica type) tightly (Fig. 3b, from K = 4 to 8). The results were consistent using two software, which indicates the clear separation of African and Asian rice. A similar clustering within the Asian cultivated rice (indica and japonica) was also observed, which actually also consistent with the clusters in nuclear genome test.

Population structure and principal component analysis of the collection. a Population structure clustering using the high-quality variations with an optimal K value of 4. b Validation of structure clustering using ADMIXTURE software. Here, an optimal K = 8 was defined. Only the structure from 4 to 8 were displayed here, since the results from K =2 to 3 were same with the results from STRUCTURE. c Principal component analysis of all of the accessions. d Multidimensional scaling (MDS) analysis of the whole collection, which can be used to prove the result from PCA. ASW: Asian wild rice, ASC: Asian cultivated rice, AFW: African wild rice, AFC: African cultivated rice. ADMIX in (a) represents the not clearly separated accessions. In (c) and (d), ADMIX indicated the three mixed accessions in the 50 cultivated and wild rice (Xu et al. 2012)

PCA using the whole variation data was conducted in TASSEL, with the first two PCs explaining more than 81.9 % of the proportional variance; therefore, we constructed the PCA using PC1 and PC2 (Fig. 3c). Four main groups were inferred, indica type, japonica type, African wild and cultivated rice, as well as several scattered accessions (Asian wild rice) and admixed among them. Multidimensional scaling (MDS) analysis was also conducted with TASSEL, which reveals four major groups that were almost same with PCA result (Fig. 3d). Even though no perfect clustering was found according to nuclear genome structure, these variations and the present case study also suggested that chloroplast genome-based analyses can be applied in population genetics studies.

Rice Phylogeny Based on the Chloroplast Genome

Phylogenetic analysis of the whole rice collection was performed using a ML iterative model-based method with a bootstrap of 1000 replicates to assess the reliability of the phylogeny reconstructed using PhyML. In parallel, phylogenetic analysis was also inferred using a Bayesian MCMC search method. The ML method suggested three clear groups (indica type, japonica type, and African rice), with the Asian wild rice scattered between indica and japonica (Fig. 4a). Most of the accessions showed clear separation into the japonica group, indica type, or African rice group, indicated by the clustering of the 50 cultivated and wild rice accessions. Similar phylogenetic results were also obtained using the BI method displayed in Fig. 4b. A comparison of the trees from two methods was implemented in a tanglegram, which reveals that the overall phylogenetic structure and clustering of the accessions in the two trees are nearly same (the same accession in two trees can connect with each other at the same location in the clusters), even the outward shape of the two trees are not well unified. The indica, japonica, and African rice groups showed almost the same clustering in two methods, but the Asian wild rice showed closer with indica group in the BI method. From the results, we inferred that indica and japonica may have an independent domestication, as the Asian wild rice was clustered between them (4 of the wild rice are mixed inside the indica and japonica group). Meanwhile, it was obvious that African rice, including cultivated (O. glaberrima) and wild (O. barthii) were in an independent group, even the wild and cultivated are not well separated. It also can be inferred that O. glaberrima was from O.barthii and have an independent domestication process distinct with O. sativa L.

A tanglegram phylogenetic analysis using trees from ML and BI methods to compare the difference of the two methods and illustrate the relationships of the different Oryza groups. Here, high-quality variations were applied in both analyses. a Phylogram and radial tree layout of the ML tree based on a best-fit model (SYM + G). b BI-based tree using the best-fit model JC + G. Best-fit models were evaluated using jModeltest. The tanglegram was implemented in Dendroscope using a Neighbor Net-based heuristic method, which use line connects the same accession in two trees to see the difference phylogenetic structure

In the TreeMix test, the subpopulation relationships were evaluated among two subsets with four and six subpopulations, which revealed that the Asian cultivated rice (indica and jaoponica) may have different origin (Fig. 5a), since the two subgroups located on different side of the Asian wild rice. By evaluating the population splits between Asian and African rice, different domestication process can be inferred since very distinct clustering was observed (Fig. 5b). When six groups were applied, similar results were obtained, and in addition, the indica is closer to the O. nivara and the japonica is closer to O.rufipogon (Fig. 5c).

TreeMix model inference to evaluate the population splits and mixtures among the populations. a Four subpopulations system in Asian rice revealed the relationships of each group. b Four subpopulations system in whole collection revealed the relationships between Asian and African rice. c Six subpopulations system in whole collection revealed the relationships between Asian and African rice. The scale bar shows ten times the average standard error of the estimated entries in the sample covariance matrix. ASW: Asian wild rice, ASC: Asian cultivated rice, AFW: African wild rice, AFC: African cultivated rice, RUF: Asian wild rice O.rufipogon, NIV: Asian wild rice O.nivara, IND: indica type in Asian cultivated rice, JAP: japonica type in Asian cultivated rice

Together with the results of previous studies regarding the origins of rice, we concluded that O. sativa L. spp. indica may have evolved from O. nivara, and that O. sativa L. spp. japonica may be domesticated from O. rufipogon. Simultaneously, African cultivated rice may have a different and separated domestication process with Asian cultivated rice.

Discussion

Genetic Variation and Population Structure in Chloroplast Genome Level

Chloroplast DNA shows a much lower substitution rate than does nuclear DNA, which is significantly reduced even in the inverted repeat regions (Wolfe et al. 1987). The overall sequence differences among rice subspecies varieties is ~130-fold higher in the nuclear than chloroplast genomes (0.12 %) (Yu et al. 2002). Therefore, in practice, detecting useful polymorphisms at the population level is difficult, due to the low substitution rates in plant chloroplast genomes. Highly accurate whole-genome sequencing and reference genome based assembly of chloroplast genome become a more economical approach and can be used for the further genomic studies (Wu et al. 2012). In this case, investigating the variations of chloroplast genome based on higher genome coverage sequencing could decrease the number of missing values and heterozygotes, and thus obtain more accurate results. In this report, we evaluated the chloroplast genome variations in a diverse collection of 383 rice accessions with relative high coverage re-sequencing, as well as the variation distribution in different groups (Table 1, Fig. 1). Intersection of variations in different groups was characterized, and only 130 variations were overlapped in four groups. While the African wild rice shown much more total and unique variations than other groups, which may indicate the huge difference between African wild and Asian rice (Fig. 6). And very few overlaps were found that only in African cultivated &Asian wild &African wild, Asian wild &African wild, African cultivated &Asian wild. Besides, considering the HQ variations, the Asian wild rice has the most variations except the African wild rice, inferring that wild type has much higher diversity than cultivated type (Table 1). Moreover, the variations showed a heterogeneity across the chloroplast genome, which leads to no variations in some specific regions (Fig. 1). The average pi of the overall genome was low (~0.0009), as were those in other groups, while the wild rice showed higher diversity than their cultivated type. A high Fst value (>0.37) was observed between the Asian and African rice, indicating their far genetics distance. Tajima’s D test in chloroplast level of African rice showed a negative value, which may indicate some purifying selection or a signature of a recent population expansion. Whereas, the Asian rice that have a positive value may indicate an over-dominant selection or population bottleneck.

Matrix layout for all intersections of four groups (ASW, ASC, AFW, AFC). Dark histogram indicated the specific variations in one group or intersected variations among two or more groups. Dark circles in the matrix indicate sets that are part of the intersection. The left set indicated the number of variations in each group. ASW: Asian wild rice, ASC: Asian cultivated rice, AFW: African wild rice, AFC: African cultivated rice

The results of the population structure analysis indicated that population clustering based on chloroplast genomes was consistent with the results based on nuclear genomes in most accessions. Besides 2 admixed accessions from the 50 cultivated and wild rice group (Group III and IV), we also found 1 indica accession, 2 African accessions, are clustered into or close to japonica and several Asian wild accessions scattered between indica and japonica were observed to be closer to indica (Fig. 3c, d). Fortunately, African rice and Asian rice can be well grouped in most accessions at the chloroplast genome level, with well clustering of African wild and cultivated rice. We can infer that the African cultivated rice has distinct genetic background with Asian rice.

Chloroplast Genome Indicates Independent Origin of Indica and Japonica

In rice, the evolutionary rate of chloroplast DNA is three-fold higher than that of mitochondrial DNA (Tian et al. 2006). Therefore, its maternal inheritance and relatively high mutation rate are useful for elucidating the phylogeny of the species. The advent of NGS (next-generation sequencing) has allowed detection of substitutions in large populations both easily and accurately, leading to a better understanding in evolutionary studies. It may not be necessary to assemble whole chloroplast genomes for molecular ecology studies by exploring chloroplast variation (McPherson et al. 2013). Chloroplast DNA provides the advantage of a high copy number without recombination, which is a critical issue in nuclear genome-based phylogenetic studies (Poke et al. 2006; Takahashi et al. 2008). Interspecific hybridization can lead to chloroplast capture, whereby the plastome of one species introgresses into another, and this has been used to explain the inconsistencies between chloroplast and nuclear gene trees.

In spite of the debate of the domestication of Asian cultivated rice (O. sativa L.), which focus on whether the two major subgroups were in single (Huang et al. 2012; Molina et al. 2011) or independent origins (Londo et al. 2006; Ma and Bennetzen 2004; Vitte et al. 2004; Yang et al. 2012; Zhu and Ge 2005), new opinion about three geographically separate domestications of Asian rice had been proposed recently (Civáň et al. 2015). From these different data and analyzing methods, different or entirely opposite result have obtained. According to Civáň et al. (2015), they got different results using the same data from Huang et al. (2012), which suggested that extreme complicated issues might happen during the long history of rice domestication in nuclear genome level complemented with the response points from Huang and Han (2015) against the new analyzing results. While the chloroplast genome can narrow down this problem for its non-recombination and high level of conservation.

Londo et al. (2006) detected the haplotype network of chloroplast atpB-rbcL region, they concluded that japonica rice is less diverse than indica rice and also demonstrated that O. sativa L. was domesticated from O. rufipogon at least twice (Khush 1997; Londo et al. 2006). A recent study of the wild and domesticated rice AA genome species using whole chloroplast genome sequences indicated that the O. rufipogon (Asian) and O. nivara are always separately clustered with japonica and indica, respectively (Wambugu et al. 2015). By applied a chloroplast genome-wide variation analysis in current report, we found the evidence support the independent domestication of Asian cultivated rice, O. sativa L. spp. indica and japonica, which were thought to be originated from O. nivara and O. rufipogon, respectively. According to a chloroplast whole genome sequence investigation from several references, we previously found that the indica and japonica were closer with O. nivara and O. rufipogon, respectively, which also indicated the independent origin of Asian cultivated rice (Tong et al. 2015). Population structure of a KRICE_CORE set, which hold 137 accessions in current collection, also supported the hypothesis of the independent origin of indica and japonica in nuclear genome (Kim et al. 2016). However, as we mentioned previously, the chloroplast genome only represents the maternal evolutionary history, which cannot be fully applied to rapidly diverging taxa. Whereas, in nuclear genome level, different dataset applied with different method sometimes generated different results. Therefore, in some cases, chloroplast genome based evolutionary studies should be complemented with nuclear genome data, and vice versa, to obtain more reliable results.

Evidence for Distinct Domestication of African Cultivated Rice

O. glaberrima was thought to be independently domesticated from the wild progenitor, Oryza barthii, ~3000 years ago (Sweeney and McCouch 2007), which is 6000–7000 years after the domestication of Asian rice (O. sativa L.) (Vaughan et al. 2008). O. glaberrima was domesticated in a single region along the Niger River, as opposed to noncentric domestication events across Africa, which has experienced geographically and culturally distinct domestication processes (Wang et al. 2014). Here, we presented evidence supporting the domestication of O. glaberrima, as well as insights into the genetic distance and population structure analyses of the chloroplast genome. In chloroplast Fst analyses, the genetic distance value (Fst) of African rice, especially African cultivated rice (O. glaberrima) with Asian rice was much higher than the distances between the other groups (Fig. 2a), indicating a low level of breeding with the Asian rice. While, a very low value was observed between African cultivated and wild rice. What observed in the population structure and principal component analyses were that African rice always classified as a separated group (Fig. 3c, d), which also can be clearly seen in the phylogenetic trees using both ML and BI methods and in the TreeMix test (Figs. 4 and 5). One more thing we need to note is that in African rice, the cultivated and wild type are not well grouped into only two clusters but intersect, which was also observed in the nuclear genome analysis conducted by Wang et al. (2014). Even though, same conclusion can be inferred according the present result. These observations indicated that O. glaberrima was distant from Asian rice and had a distinct domestication process at chloroplast genome level.

Conclusions

In current report, we described chloroplast variation architecture of 383 rice accessions from diverse regions and different ecotypes. A total of 3677 variations across the chloroplast genome were identified. The chloroplast genome variation architecture in Asian and African rice are different, as well as within Asian or African rice. Wild rice and cultivated rice also have distinct nucleotide diversity or genetic distance. Chloroplast genome nucleotide diversity and genetic distance were investigated, indicated a high degree of diversity in wild rice than in cultivated rice. African rice showed a low level of breeding and connectivity with the Asian rice, suggesting the big distinction of them. Population structure and principal component analysis revealed the existence of clear clustering of African and Asian rice, as well as the indica and japonica in Asian cultivated rice. Phylogenetic analysis and the population splits test suggested and supported the independent origins of indica and japonica within Asian cultivated rice. In addition, the African cultivated rice was thought to be domesticated differently from Asian cultivated rice. We hope these results could provide more candidate evidence for the further rice chloroplast genomic and evolution studies.

Methods

Samples and Whole-Genome Resequencing

A core set containing 137 rice accessions with diverse types (landrace, weedy, cultivated) previously generated from worldwide varieties collected from the National Genebank of the Rural Development Administration (RDA-Genebank, Republic of Korea) using the program PowerCore (Kim et al. 2007; Zhao et al. 2010; Kim et al. 2016) and 158 bred accessions were selected and sequenced for chloroplast genomic evaluation (Additional file 7: Table S5). In addition, 50 accessions of cultivated and wild rice developed by Xu et al. (Xu et al. 2012) and 19 accessions of African cultivated rice (O. glaberrima) and 19 accessions of African wild rice (O. barthii) (Wang et al. 2014) were also combined in the present study (Additional file 8: Table S6). Raw data from the 50 cultivated and wild rice, 19 African cultivated rice, and 19 African wild rice accessions were downloaded from the European Nucleotide Archive (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/ena) under accession numbers [SRA023116, SRP038750, and SRP037996] respectively.

For our germplasm (295 accessions with diverse origin), young leaves from a single plant were sampled and stored at –80°C prior to genomic DNA extraction using the DNeasy Plant Mini Kit (Qiagen). Qualified DNA was used for whole-genome resequencing of the collected rice varieties (295 accessions), with an average coverage of approximately 7.34× on the Illumina HiSeq 2000 Sequencing Systems Platform (Illumina Inc.).

Data preparation, Identification of Variation, and Statistics

Resequencing raw data (Fastq format) of all the accessions were trimmed using Sickle v1.2 (Joshi and Fass 2011) to remove low-quality reads. BWA v0.6.2 (Li and Durbin 2009) was used to align the raw data to the O. rufipogon chloroplast genome sequence. A Sequence Alignment/Map (SAM) file was created during the mapping and converted to a binary SAM (BAM) file with sorting. Removal of duplicates and addition of read group IDs were performed using Picard Tools v1.88 (https://broadinstitute.github.io/picard/). Final realignment and identification of variation were performed using GATK software v3 (McKenna et al. 2010). The variant call format file describing the variation result was processed by two python scripts, generating a HapMap (Haplotype Map) file.

Statistical analyses were performed to summarize the number and distribution of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) and indels (insertions and deletions) based on the HapMap file. The positions of high-quality (HQ, sites without missing and MAF ≥ 0.01, determined by the smallest group number 5 both in O. nivara and O. rufipogon) SNPs and indels in this population and subgroups were established according to the reference genome of O. rufipogon. For the Asian cultivated group, three admixed accessions in the 50 cultivated and wild rice were excluded for the further subgroup comparative analyses.

Chloroplast Genome Diversity Architecture

Analyses of chloroplast genome nucleotide diversity (pi), population divergence (Fst value), Ts/Tv (Transition/Transversion ratio) and Tajima’s D value were conducted using VCFtools (Danecek et al. 2011). Assessments of these calculations in whole collection and different subgroups (Asian cultivated and wild, African cultivated and wild) were performed using VCFtools with a sliding window 1000 bp in length and a 500-bp step size.

Population Structure and Principal Component Analysis

The population structures of the collection were investigated using the model-based program STRUCTURE v2.3.4 (Pritchard et al. 2000) with a burn-in period length of 100,000 and a Markov chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) rep number of 200,000, which implements a Bayesian approach to identify subpopulations with distinct allelic frequencies and places individuals into K clusters. The distribution of L (K) revealed a continuously increasing curve without a clear maximum for true K. To overcome these difficulties in identifying the true K value, an ad hoc quantity (ΔK) was calculated based on the second-order rate of change of likelihood (∆K) using the software Structure Harvest (Evanno et al. 2005; Earl 2012). Besides, the population structure was also validated using another model-based software ADMIXTURE (Alexander et al. 2009). By using ADMIXTURE’s cross-validation procedure, a good value of K can be obtained, which will exhibit a low cross-validation error compared to other K values. Principal component analysis (PCA) and multidimensional scaling (MDS) was conducted using TASSEL 5 (Bradbury et al. 2007), which could provide more evidence and complement the population structure analyses. MDS produces results that are similar to PCA but starts with a distance matrix and results in coordinate axes that are scaled differently.

Chloroplast-Based Phylogenetic and Population Splits

ML and BI methods were applied to construct a phylogenetic tree for all 383 accessions. Briefly, appropriate nucleotide substitution models were assessed using jModeltest 2.1.7 (Darriba et al. 2012). A phylogenetic tree was conducted using PhyML 3.0 (Guindon et al. 2010) complemented by the best nucleotide substitution model SYM + G (symmetrical model + gamma distribution) selected by the hierarchical LRT (Hierarchical Likelihood Ratio Test) (Felsenstein 1988) and the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) (Akaike 1974) with 1000 bootstrap replicates. A Bayesian tree was constructed using MrBayes 3.2.5 (Ronquist et al. 2012) implemented with a Bayesian MCMC search, with two parallel runs of 2 million generations and four chains each. Best-fit model JC + G (Jukes-Cantor + gamma distribution) were selected according to the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) (Schwarz 1978). The phylogenetic tree was displayed and modified using Figtree v1.4.2 (http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree/). The consensus tree of the bootstrap in the ML method was integrated using Phylip software (Phylogeny Inference Package v3.695, http://evolution.genetics.washington.edu/phylip.html). A tanglegram for two trees was implemented in Dendroscope (Huson and Scornavacca 2012) using a Neighbor Net-based heuristic, which is one good way to visualize similarities and differences between two phylogenetic trees side by side connected with lines between taxa that correspond to each other.

Additionally, a TreeMix model for inferring the set of population splits and mixtures in the history of a set of populations was performed using genome-wide allele frequency data in TreeMix (Pickrell and Pritchard 2012). In the collection, four (African cultivated and wild, Asian cultivated and wild, as well as the four groups of Asian rice) and six subpopulations (African wild and cultivated rice, Asian wild and cultivated rice, and the indica and japonica groups in Asian cultivated rice) were implemented to identify the relationships among the populations.

References

Akaike H (1974) A new look at the statistical model identification. IEEE Trans Automatic Control 19(6):716–723

Alexander DH, Novembre J, Lange K (2009) Fast model-based estimation of ancestry in unrelated individuals. Genome Res 19:1655–1664

Bradbury PJ, Zhang Z, Kroon DE, Casstevens TM, Ramdoss Y, Buckler ES (2007) TASSEL: software for association mapping of complex traits in diverse samples. Bioinformatics 23(19):2633–2635. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btm308

Brozynska M, Omar ES, Furtado A, Crayn D, Simon B, Ishikawa R, Henry RJ (2014) Chloroplast genome of novel rice germplasm identified in Northern Australia. Trop Plant Biol 7(3-4):111–120. doi:10.1007/s12042-014-9142-8

Carbonell-Caballero J, Alonso R, Ibanez V, Terol J, Talon M, Dopazo J (2015) A phylogenetic analysis of 34 chloroplast genomes elucidates the relationships between wild and domestic species within the genus citrus. Mol Biol Evol 32(8):2015–2035. doi:10.1093/molbev/msv082

Cheng C, Motohashi R, Tsuchimoto S, Fukuta Y, Ohtsubo H, Ohtsubo E (2003) Polyphyletic origin of cultivated rice: based on the interspersion pattern of SINEs. Mol Biol Evol 20(1):67–75

Civáň P, Craig H, Cox CJ, Brown TA (2015) Three geographically separate domestications of Asian rice. Nat Plants 1:15164

Danecek P, Auton A, Abecasis G, Albers CA, Banks E, DePristo MA, Handsaker RE, Lunter G, Marth GT, Sherry ST, McVean G, Durbin R, Genomes Project Analysis G (2011) The variant call format and VCFtools. Bioinformatics 27(15):2156–2158. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btr330

Darriba D, Taboada GL, Doallo R, Posada D (2012) jModelTest 2: more models, new heuristics and parallel computing. Nat Methods 9(8):772. doi:10.1038/nmeth.2109

De Las Rivas J, Lozano JJ, Ortiz AR (2002) Comparative analysis of chloroplast genomes: functional annotation, genome-based phylogeny, and deduced evolutionary patterns. Genome Res 12(4):567–583. doi:10.1101/gr.209402

Earl DA (2012) STRUCTURE HARVESTER: a website and program for visualizing STRUCTURE output and implementing the Evanno method. Conserv Genet Resour 4(2):359–361

Evanno G, Regnaut S, Goudet J (2005) Detecting the number of clusters of individuals using the software STRUCTURE: a simulation study. Mol Ecol 14(8):2611–2620. doi:10.1111/j.1365-294X.2005.02553.x

Felsenstein J (1988) Phylogenies from molecular sequences: inference and reliability. Annu Rev Genet 22:521–565. doi:10.1146/annurev.ge.22.120188.002513

Garris AJ, Tai TH, Coburn J, Kresovich S, McCouch S (2005) Genetic structure and diversity in Oryza sativa L. Genetics 169(3):1631–1638. doi:10.1534/genetics.104.035642

Goff SA, Ricke D, Lan TH, Presting G, Wang R, Dunn M, Glazebrook J, Sessions A, Oeller P, Varma H, Hadley D, Hutchison D, Martin C, Katagiri F, Lange BM, Moughamer T, Xia Y, Budworth P, Zhong J, Miguel T, Paszkowski U, Zhang S, Colbert M, Sun WL, Chen L, Cooper B, Park S, Wood TC, Mao L, Quail P, Wing R, Dean R, Yu Y, Zharkikh A, Shen R, Sahasrabudhe S, Thomas A, Cannings R, Gutin A, Pruss D, Reid J, Tavtigian S, Mitchell J, Eldredge G, Scholl T, Miller RM, Bhatnagar S, Adey N, Rubano T, Tusneem N, Robinson R, Feldhaus J, Macalma T, Oliphant A, Briggs S (2002) A draft sequence of the rice genome (Oryza sativa L. ssp. japonica). Science 296(5565):92–100. doi:10.1126/science.1068275

Guindon S, Dufayard JF, Lefort V, Anisimova M, Hordijk W, Gascuel O (2010) New algorithms and methods to estimate maximum-likelihood phylogenies: assessing the performance of PhyML 3.0. Syst Biol 59(3):307–321. doi:10.1093/sysbio/syq010

Hagemann R (2010) The foundation of extranuclear inheritance: plastid and mitochondrial genetics. Mol Genet Genomics 283(3):199–209. doi:10.1007/s00438-010-0521-z

Hiratsuka J, Shimada H, Whittier R, Ishibashi T, Sakamoto M, Mori M, Kondo C, Honji Y, Sun CR, Meng BY et al (1989) The complete sequence of the rice (Oryza sativa) chloroplast genome: intermolecular recombination between distinct tRNA genes accounts for a major plastid DNA inversion during the evolution of the cereals. Mol Gen Genet 217(2-3):185–194

Huang X, Han B (2015) Rice domestication occurred through single origin and multiple introgressions. Nat Plants 1:15207

Huang X, Kurata N, Wei X, Wang ZX, Wang A, Zhao Q, Zhao Y, Liu K, Lu H, Li W, Guo Y, Lu Y, Zhou C, Fan D, Weng Q, Zhu C, Huang T, Zhang L, Wang Y, Feng L, Furuumi H, Kubo T, Miyabayashi T, Yuan X, Xu Q, Dong G, Zhan Q, Li C, Fujiyama A, Toyoda A, Lu T, Feng Q, Qian Q, Li J, Han B (2012) A map of rice genome variation reveals the origin of cultivated rice. Nature 490(7421):497–501. doi:10.1038/nature11532

Huson DH, Scornavacca C (2012) Dendroscope 3: an interactive tool for rooted phylogenetic trees and networks. Syst Biol 61(6):1061–1067. doi:10.1093/sysbio/sys062

Ishii T, Xu Y, McCouch S (2001) Nuclear-and chloroplast-microsatellite variation in A-genome species of rice. Genome 44(4):658–666

Jin J, Huang W, Gao JP, Yang J, Shi M, Zhu MZ, Luo D, Lin HX (2008) Genetic control of rice plant architecture under domestication. Nat Genet 40(11):1365–1369. doi:10.1038/ng.247

Joshi N, Fass J (2011) Sickle: A sliding-window, adaptive, quality-based trimming tool for FastQ files (Version 1.33) [Software]. Available at https://github.com/najoshi/sickle

Kato T, Kaneko T, Sato S, Nakamura Y, Tabata S (2000) Complete structure of the chloroplast genome of a legume, Lotus japonicus. DNA Res 7(6):323–330

Kawakami S, Ebana K, Nishikawa T, Sato Y, Vaughan DA, Kadowaki K (2007) Genetic variation in the chloroplast genome suggests multiple domestication of cultivated Asian rice (Oryza sativa L.). Genome 50(2):180–187. doi:10.1139/g06-139

Khush GS (1997) Origin, dispersal, cultivation and variation of rice. Plant Mol Biol 35(1-2):25–34

Kim H, Jeong EG, Ahn S-N, Doyle J, Singh N, Greenberg AJ, Won YJ, McCouch SR (2014) Nuclear and chloroplast diversity and phenotypic distribution of rice (Oryza sativa L.) germplasm from the democratic people’s republic of Korea (DPRK; North Korea). Rice 7(1):1–15

Kim KW, Chung HK, Cho GT, Ma KH, Chandrabalan D, Gwag JG, Kim TS, Cho EG, Park YJ (2007) PowerCore: a program applying the advanced M strategy with a heuristic search for establishing core sets. Bioinformatics 23(16):2155–2162. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btm313

Kim T-S, He Q, Kim K-W, Yoon M-Y, Ra W-H, Li FP, Tong W, Yu J, Oo WH, Choi B (2016) Genome-wide resequencing of KRICE_CORE reveals their potential for future breeding, as well as functional and evolutionary studies in the post-genomic era. BMC Genomics 17(1):1

King RA, Ferris C (2000) Chloroplast DNA and nuclear DNA variation in the sympatric alder species, Alnus cordata (Lois.) Duby and A. glutinosa (L.) Gaertn. Biol J Linn Soc 70(1):147–160

Kohler S, Delwiche CF, Denny PW, Tilney LG, Webster P, Wilson RJ, Palmer JD, Roos DS (1997) A plastid of probable green algal origin in Apicomplexan parasites. Science 275(5305):1485–1489

Li C, Zhou A, Sang T (2006) Rice domestication by reducing shattering. Science 311(5769):1936–1939. doi:10.1126/science.1123604

Li H, Durbin R (2009) Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 25(14):1754–1760. doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324

Londo JP, Chiang YC, Hung KH, Chiang TY, Schaal BA (2006) Phylogeography of Asian wild rice, Oryza rufipogon, reveals multiple independent domestications of cultivated rice, Oryza sativa. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103(25):9578–9583. doi:10.1073/pnas.0603152103

Ma J, Bennetzen JL (2004) Rapid recent growth and divergence of rice nuclear genomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 101(34):12404–12410. doi:10.1073/pnas.0403715101

McKenna A, Hanna M, Banks E, Sivachenko A, Cibulskis K, Kernytsky A, Garimella K, Altshuler D, Gabriel S, Daly M, DePristo MA (2010) The Genome Analysis Toolkit: a MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res 20(9):1297–1303. doi:10.1101/gr.107524.110

McPherson H, van der Merwe M, Delaney SK, Edwards MA, Henry RJ, McIntosh E, Rymer PD, Milner ML, Siow J, Rossetto M (2013) Capturing chloroplast variation for molecular ecology studies: a simple next generation sequencing approach applied to a rainforest tree. BMC Ecol 13:8. doi:10.1186/1472-6785-13-8

Molina J, Sikora M, Garud N, Flowers JM, Rubinstein S, Reynolds A, Huang P, Jackson S, Schaal BA, Bustamante CD, Boyko AR, Purugganan MD (2011) Molecular evidence for a single evolutionary origin of domesticated rice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108(20):8351–8356. doi:10.1073/pnas.1104686108

Moore MJ, Soltis PS, Bell CD, Burleigh JG, Soltis DE (2010) Phylogenetic analysis of 83 plastid genes further resolves the early diversification of eudicots. Proc Natl Acad Sci 107(10):4623–4628

Nikiforova SV, Cavalieri D, Velasco R, Goremykin V (2013) Phylogenetic analysis of 47 chloroplast genomes clarifies the contribution of wild species to the domesticated apple maternal line. Mol Biol Evol 30(8):1751–1760. doi:10.1093/molbev/mst092

Nock CJ, Waters DL, Edwards MA, Bowen SG, Rice N, Cordeiro GM, Henry RJ (2011) Chloroplast genome sequences from total DNA for plant identification. Plant Biotechnol J 9(3):328–333. doi:10.1111/j.1467-7652.2010.00558.x

Oka HI (1988) Origin of cultivated rice. Developments in crop science, vol 14. Japan Scientific Societies Press; Elsevier; Exclusive sales rights for the U.S.A. and Canada, Elsevier Science Pub. Co., Tokyo Amsterdam Netherlands; New York, N.Y.

Palmer JD, Jansen RK, Michaels HJ, Chase MW, Manhart JR (1988) Chloroplast DNA variation and plant phylogeny. Ann Mo Bot Gard 75(4):1180–1206

Parks M, Cronn R, Liston A (2009) Increasing phylogenetic resolution at low taxonomic levels using massively parallel sequencing of chloroplast genomes. BMC Biol 7(1):84

Pickrell JK, Pritchard JK (2012) Inference of population splits and mixtures from genome-wide allele frequency data. PLoS Genet 8(11):e1002967

Poke FS, Martin DP, Steane DA, Vaillancourt RE, Reid JB (2006) The impact of intragenic recombination on phylogenetic reconstruction at the sectional level in Eucalyptus when using a single copy nuclear gene (cinnamoyl CoA reductase). Mol Phylogenet Evol 39(1):160–170. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2005.11.016

Pritchard JK, Stephens M, Donnelly P (2000) Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data. Genetics 155(2):945–959

Provan J, Corbett G, Powell W, McNicol J (1997) Chloroplast DNA variability in wild and cultivated rice (Oryza spp.) revealed by polymorphic chloroplast simple sequence repeats. Genome 40(1):104–110

Ronquist F, Teslenko M, van der Mark P, Ayres DL, Darling A, Hohna S, Larget B, Liu L, Suchard MA, Huelsenbeck JP (2012) MrBayes 3.2: efficient Bayesian phylogenetic inference and model choice across a large model space. Syst Biol 61(3):539–542. doi:10.1093/sysbio/sys029

Schroeder H, Höltken A, Fladung M (2011) Chloroplast SNP-marker as powerful tool for differentiation of Populus species in reliable poplar breeding and barcoding approaches. BMC Proc 5(Suppl 7):56, BioMed Central Ltd

Schwarz G (1978) Estimating the dimension of a model. Ann Stat 6(2):461–464

Soejima A, Wen J (2006) Phylogenetic analysis of the grape family (Vitaceae) based on three chloroplast markers. Am J Bot 93(2):278–287. doi:10.3732/ajb.93.2.278

Straub SC, Parks M, Weitemier K, Fishbein M, Cronn RC, Liston A (2012) Navigating the tip of the genomic iceberg: Next-generation sequencing for plant systematics. Am J Bot 99(2):349–364. doi:10.3732/ajb.1100335

Sugiura M (1989) The chloroplast chromosomes in land plants. Annu Rev Cell Biol 5:51–70. doi:10.1146/annurev.cb.05.110189.000411

Sweeney M, McCouch S (2007) The complex history of the domestication of rice. Ann Bot 100(5):951–957. doi:10.1093/aob/mcm128

Takahashi H, Y-i S, Nakamura I (2008) Evolutionary analysis of two plastid DNA sequences in cultivated and wild species of Oryza. Breed Sci 58(3):225–233. doi:10.1270/jsbbs.58.225

Tang J, Xia H, Cao M, Zhang X, Zeng W, Hu S, Tong W, Wang J, Wang J, Yu J, Yang H, Zhu L (2004) A comparison of rice chloroplast genomes. Plant Physiol 135(1):412–420. doi:10.1104/pp.103.031245

Tian X, Zheng J, Hu S, Yu J (2006) The rice mitochondrial genomes and their variations. Plant Physiol 140(2):401–410. doi:10.1104/pp.105.070060

Tong W, He Q, Wang XQ, Yoon MY, Ra WH, Li F, Yu J, Oo WH, Min SK, Choi BW (2015) A chloroplast variation map generated using whole genome re‐sequencing of Korean landrace rice reveals phylogenetic relationships among Oryza sativa subspecies. Biol J Linn Soc 115(4):940–952

Turmel M, Otis C, Lemieux C (1999) The complete chloroplast DNA sequence of the green alga Nephroselmis olivacea: insights into the architecture of ancestral chloroplast genomes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 96(18):10248–10253

Vaughan DA, Lu B-R, Tomooka N (2008) The evolving story of rice evolution. Plant Sci 174(4):394–408

Vitte C, Ishii T, Lamy F, Brar D, Panaud O (2004) Genomic paleontology provides evidence for two distinct origins of Asian rice (Oryza sativa L.). Mol Genet Genomics 272(5):504–511. doi:10.1007/s00438-004-1069-6

Wambugu PW, Brozynska M, Furtado A, Waters DL, Henry RJ (2015) Relationships of wild and domesticated rices (Oryza AA genome species) based upon whole chloroplast genome sequences. Sci Rep 5:13957

Wang M, Yu Y, Haberer G, Marri PR, Fan C, Goicoechea JL, Zuccolo A, Song X, Kudrna D, Ammiraju JS, Cossu RM, Maldonado C, Chen J, Lee S, Sisneros N, de Baynast K, Golser W, Wissotski M, Kim W, Sanchez P, Ndjiondjop MN, Sanni K, Long M, Carney J, Panaud O, Wicker T, Machado CA, Chen M, Mayer KF, Rounsley S, Wing RA (2014) The genome sequence of African rice (Oryza glaberrima) and evidence for independent domestication. Nat Genet 46(9):982–988. doi:10.1038/ng.3044

Waters DL, Nock CJ, Ishikawa R, Rice N, Henry RJ (2012) Chloroplast genome sequence confirms distinctness of Australian and Asian wild rice. Ecol Evol 2(1):211–217. doi:10.1002/ece3.66

Wolfe KH, Li WH, Sharp PM (1987) Rates of nucleotide substitution vary greatly among plant mitochondrial, chloroplast, and nuclear DNAs. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 84(24):9054–9058

Wu J, Liu B, Cheng F, Ramchiary N, Choi SR, Lim YP, Wang XW (2012) Sequencing of chloroplast genome using whole cellular DNA and solexa sequencing technology. Front Plant Sci 3:243. doi:10.3389/fpls.2012.00243

Xu X, Liu X, Ge S, Jensen JD, Hu F, Li X, Dong Y, Gutenkunst RN, Fang L, Huang L, Li J, He W, Zhang G, Zheng X, Zhang F, Li Y, Yu C, Kristiansen K, Zhang X, Wang J, Wright M, McCouch S, Nielsen R, Wang J, Wang W (2012) Resequencing 50 accessions of cultivated and wild rice yields markers for identifying agronomically important genes. Nat Biotechnol 30(1):105–111. doi:10.1038/nbt.2050

Yang CC, Kawahara Y, Mizuno H, Wu J, Matsumoto T, Itoh T (2012) Independent domestication of Asian rice followed by gene flow from japonica to indica. Mol Biol Evol 29(5):1471–1479. doi:10.1093/molbev/msr315

Yang JB, Tang M, Li HT, Zhang ZR, Li DZ (2013) Complete chloroplast genome of the genus Cymbidium: lights into the species identification, phylogenetic implications and population genetic analyses. BMC Evol Biol 13:84. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-13-84

Yu J, Hu S, Wang J, Wong GK, Li S, Liu B, Deng Y, Dai L, Zhou Y, Zhang X, Cao M, Liu J, Sun J, Tang J, Chen Y, Huang X, Lin W, Ye C, Tong W, Cong L, Geng J, Han Y, Li L, Li W, Hu G, Huang X, Li W, Li J, Liu Z, Li L, Liu J, Qi Q, Liu J, Li L, Li T, Wang X, Lu H, Wu T, Zhu M, Ni P, Han H, Dong W, Ren X, Feng X, Cui P, Li X, Wang H, Xu X, Zhai W, Xu Z, Zhang J, He S, Zhang J, Xu J, Zhang K, Zheng X, Dong J, Zeng W, Tao L, Ye J, Tan J, Ren X, Chen X, He J, Liu D, Tian W, Tian C, Xia H, Bao Q, Li G, Gao H, Cao T, Wang J, Zhao W, Li P, Chen W, Wang X, Zhang Y, Hu J, Wang J, Liu S, Yang J, Zhang G, Xiong Y, Li Z, Mao L, Zhou C, Zhu Z, Chen R, Hao B, Zheng W, Chen S, Guo W, Li G, Liu S, Tao M, Wang J, Zhu L, Yuan L, Yang H (2002) A draft sequence of the rice genome (Oryza sativa L. ssp. indica). Science 296(5565):79–92. doi:10.1126/science.1068037

Zhang LB, Zhu Q, Wu ZQ, Ross-Ibarra J, Gaut BS, Ge S, Sang T (2009) Selection on grain shattering genes and rates of rice domestication. New Phytol 184(3):708–720. doi:10.1111/j.1469-8137.2009.02984.x

Zhao W, Cho G-T, Ma K-H, Chung J-W, Gwag J-G, Park Y-J (2010) Development of an allele-mining set in rice using a heuristic algorithm and SSR genotype data with least redundancy for the post-genomic era. Mol Breed 26(4):639–651

Zhu BF, Si L, Wang Z, Zhou Y, Zhu J, Shangguan Y, Lu D, Fan D, Li C, Lin H, Qian Q, Sang T, Zhou B, Minobe Y, Han B (2011) Genetic control of a transition from black to straw-white seed hull in rice domestication. Plant Physiol 155(3):1301–1311. doi:10.1104/pp.110.168500

Zhu Q, Ge S (2005) Phylogenetic relationships among A‐genome species of the genus Oryza revealed by intron sequences of four nuclear genes. New Phytol 167(1):249–265

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a grant from the BioGreen 21 Program (No. PJ01116101), Rural Development Administration, Republic of Korea. We also thank the anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments.

Availability of Data and Materials

The datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are included within the article and its additional files. In addition, the raw VCF file generated from current 383 rice accessions was also deposited in the NCBI dbSNP Database under the NCBI ss ID from 2095231732 to 2095235306, and will be publicly available in the next dbSNP Build (B150), which is planned in Spring, 2017.

Authors’ Contributions

YP led and conceived the manuscript. YP, TK developed the idea, editing and revised the manuscript. WT did the data analysis and wrote the text of the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional Files

Additional file 1: Table S1.

Summary of the 295 rice whole genome re-sequencing. (XLSX 30 kb)

Additional file 2: Table S2.

Location of all the SNPs and Indels and their gene region in the reference detected in this study. (XLSX 121 kb)

Additional file 3: Figure S1.

Overall Ts/Tv (Transition/ Transversion ratio) in 1kb bins of the whole collection and different groups. ASW: Asian wild rice, ASC: Asian cultivated rice, AFW: African wild rice, AFC: African cultivated rice. (DOCX 78 kb)

Additional file 4: Table S3.

Nucleotide diversity of the overall chloroplast genome with a 1000bp sliding window and 500bp step size. (XLSX 16 kb)

Additional file 5: Table S4.

Overall Tajima’s D testing of the chloroplast genome in a 1kb bin. (XLSX 13 kb)

Additional file 6: Figure S2.

Magnitude of ΔK as a function of K and cross-validation error estimation to find the optimal K value for the population structure in STRUCTURE and ADMIXTURE. In this case, the maximum value of ΔK for all of the accessions was identified as K = 4 in STRUCTURE. While a lowest error value in K = 8 was identified in ADMIXTURE. But the values were similar from K = 5 to 10. (DOCX 58 kb)

Additional file 7: Table S5.

The 295 accessions information sequenced by ourselves and subpopulation designations used in this study. (DOCX 31 kb)

Additional file 8: Table S6.

Fifty cultivated and wild rice accessions and 38 African rice (including 19 African cultivated rice and 19 African wild rice) accessions used in the chloroplast genome study. (DOCX 21 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Tong, W., Kim, TS. & Park, YJ. Rice Chloroplast Genome Variation Architecture and Phylogenetic Dissection in Diverse Oryza Species Assessed by Whole-Genome Resequencing. Rice 9, 57 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12284-016-0129-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12284-016-0129-y