Abstract

Background

Fetal exposure to a maternal low protein diet during rat pregnancy is associated with hypertension, renal dysfunction and metabolic disturbance in adult life. These effects are present when dietary manipulations target only the first half of pregnancy. It was hypothesised that early gestation protein restriction would impact upon placental gene expression and that this may give clues to the mechanism which links maternal diet to later consequences.

Methods

Pregnant rats were fed control or a low protein diet from conception to day 13 gestation. Placentas were collected and RNA sequencing performed using the Illumina platform.

Results

Protein restriction down-regulated 67 genes and up-regulated 24 genes in the placenta. Ingenuity pathway analysis showed significant enrichment in pathways related to cholesterol and lipoprotein transport and metabolism, including atherosclerosis signalling, clathrin-mediated endocytosis, LXR/RXR and FXR/RXR activation. Genes at the centre of these processes included the apolipoproteins ApoB, ApoA2 and ApoC2, microsomal triglyceride transfer protein (Mttp), the clathrin-endocytosis receptor cubilin, the transcription factor retinol binding protein 4 (Rbp4) and transerythrin (Ttr; a retinol and thyroid hormone transporter). Real-time PCR measurements largely confirmed the findings of RNASeq and indicated that the impact of protein restriction was often striking (cubilin up-regulated 32-fold, apoC2 up-regulated 17.6-fold). The findings show that gene expression in specific pathways is modulated by maternal protein restriction in the day-13 rat placenta.

Conclusions

Changes in cholesterol transport may contribute to altered tissue development in the fetus and hence programme risk of disease in later life.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The causes of chronic diseases of adulthood are complex. In addition to influences of adult lifestyle, such as dietary pattern, physical activity and the consumption of alcohol and smoking, the environment experienced during infancy and fetal life plays a critical role in establishing adult metabolic and cardiovascular phenotypes [1]. Early life exposure to poor nutrition (both under- and over-nutrition) can programme aspects of adult anatomy, physiology and metabolism [2, 3]. Risk of cardiovascular and metabolic disorders that emerge later in life may therefore already in place even before birth. Epidemiological studies which show relationships between proxy markers of poor nutrition in pregnancy and diseases including cardiovascular disease, type-2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease are supported by observations in animals [2, 4–6]. Manipulating either overall food supply or dietary composition such that one or more nutrients is limiting during pregnancy leads to permanent changes in organ structure and establishes a predisposition to ageing-related insulin resistance, cardiovascular dysfunction and renal disease [1].

We previously showed that exposure of the developing rat fetus to maternal undernutrition (both protein restriction and iron deficiency) up to day 13 gestation (full-term is 22 days) induced changes in renal morphology that may underpin the development of hypertension in later life [7]. These effects were associated with a number of changes in the expression of genes and proteins in the day 13 embryo, which were clustered around regulation of the cell cycle, the cytoskeleton and formation of clathrin vesicles [7, 8]. Whilst these processes within the embryo can be envisaged as contributing to remodelling of tissues and therefore permanent changes in the physiology of the animal, leading to later disease [9], they do not give an indication of what initiates these changes in response to maternal diet.

The placenta has long been recognised as having an important role in nutritional programming of later disease [10] either through dietary modulation of placentally derived hormones, dietary modulation of the placental transport of hormones [11] or variation in the delivery of key substrates to the developing fetus [12]. As such, it may be at the centre of the response to maternal undernutrition and the transfer of signals of adverse conditions from mother to fetus. Placental functions will vary with stage of development and the demands of the fetus. In this study, we have focused on the day-13 rat placenta. At this point, full development of the organ has not been completed, but all five basic placental layers are in place (myometrium, deciduum, giant trophoblasts, trophospongium and labyrinth; [13]. The tissue is rich in blood cells and glycogen cells but has not yet developed invasive vessels [13]. In the rat, maximum placental weight is not reached until day 16. We hypothesised that the established but immature placenta would show differential patterns of gene expression in response to maternal protein restriction. These patterns may give important clues as to how maternal nutrition at this stage of development may have long-term consequences for the fetus.

Methods

This paper reports data from analysis of placentas collected in our previously published study of gene and protein expression in day-13 rat embryos [7]. Female virgin Wistar rats (Harlan, UK) were subjected to a 12 h light (08:00–20:00)-dark (20:00–08:00) cycle at a temperature of 20–22 °C with ad libitum access to food and water. At a weight of approximately 180–200 g, females were mated with stud males. After conception, determined by the presence of a semen plug on the cage floor, females were single-housed and animals were fed either a control 18 % (w/w) casein protein diet (control protein (CP)) or a 9 % (w/w) casein (low protein (LP)) diet until day 13 gestation (n = 8 per group). The LP diet was isocaloric relative to the control (see Additional file 1: Table S1 for composition of diets). To achieve a 50 % reduction in protein content of the LP diet, an additional 9 % carbohydrate was added. We have previously discussed the relative contributions of protein, carbohydrate and lipids to programming effects of the diet in detail [14–16]. During pregnancy, the animals were weighed and food intake was recorded daily. All animal work was performed under licence from the Home Office (UK) and complied with the Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act (1986). The project was approved by the University of Nottingham, Animal Ethics Committee.

On day 13 of gestation the rats were culled by CO2 asphyxia and cervical dislocation. Individual embryos and placentas were harvested. Tails were removed from embryos to establish sex. Tissues were snap frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C. PCR was used to verify presence or absence of the sex determining region-Y (SRY) gene in lysed embryo tail tissue [7]. This study used placenta only from male embryos and to generate the RNA samples for RNASeq analysis three placentas from the same litter were pooled. Only male embryos were selected to remove complications of sex from the analysis. Previous work has shown that the impact of maternal undernutrition upon long-term health of offspring is greater in males than in females [17–19]. Overall six samples per group were used for the analysis, with each sample representing three placentas associated with male embryos from a separate litter (18 placentas, 6 litters per group).

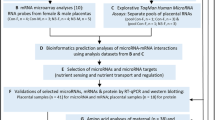

High-quality RNA was prepared from frozen tissue using Roche High Pure Tissue Kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Samples of high-quality RNA (RIN >6.0) were sent to Oxford Gene Technology (Begbrooke, Oxfordshire, UK) for polyA-enriched RNA sequencing using the Illumina TruSeq RNA sample prep kit v2 (Illumina, Little Chesterford, Essex, UK). With this kit, total RNA was captured using olido-dT coated magnetic beads and messenger RNA (mRNA) was fragmented and randomly primed. First strand complementary DNA (cDNA) was initiated from random primers, followed by second strand synthesis. After end repair, phosphorylation and A-tailing, adapter ligation and PCR amplification was performed to prepare the library for sequencing.

Sequencing was performed on the Illumina HiSeq2000 platform using TruSeq v3 chemistry. Read files (Fastq) were generated from the sequencing platform via the manufacturer’s proprietary software, and read level QC metrics were generated by FastQC http://www.bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/). Reads were processed through the Tuxedo suite [20] and mapped to their location using Bowtie version 2.o2 (http://bowtie-bio.sourceforge.net/index.shtml). Cufflinks v2.1.1 (http://cole-trapnell-lab.github.io/cufflinks/) was used to perform transcript assembly, abundance estimation and differential expression for the samples. RNASeq alignment metrics were generated using Picard tools (http://broadinstitute.github.io/picard/).

RNASeq was carried out on 12 samples with an average of 12279507 paired end reads per sample. A total of 11.63 gigabases of sequence data were read and aligned at high quality. The number of mapped reads per sample ranged from 3081828 to 17579532, and the proportion of mapped reads exceeded 99 % across all samples. The percentage of high-quality aligned bases was in excess of 98.5 and >96.5 % of reads were aligned in pairs.

Data was analysed using Cufflinks v2.1.1. A one-sided t test was used to determine the significant changes in gene expression (P value), and a Benjamini-Hochberg correction for multiple testing was also used (q value) as reported by Trapnell et al. [21]. Selection of genes identified as differentially expressed in the protein restricted group was based upon false discovery rate adjusted q values <0.05 (unadjusted P < 0.0005). Pathways and networks of interacting proteins enriched for differentially expressed genes were identified using ingenuity pathway analysis. Statistical enrichment is calculated by a right tailed Fisher’s exact test (IPA, QIAGEN Redwood City www.qiagen.com/ingenuity).

To further explore the differential expression data, we performed quantitative real-time PCR for 13 genes that were differentially expressed according to the RNASeq analysis. These included seven genes in the main pathways showing enrichment in the ingenuity analysis (ApoA2, ApoC2, Ttr, Fgg, Actg2, serpin G1 and Rbp4); Cubn and Mttp, which have functions closely related to those enriched pathways; and four genes that were shown to be differentially expressed in the protein restricted condition (Vil1, Gpc3, Muc13, Prf1). The PCR measurements were performed on the same RNA samples that were originally analysed through RNASeq. Total RNA (500 ng) was reverse transcribed using a cDNA synthesis kit (RevertAid RT Reverse Transcription Kit, Thermo Fisher) with random primers. Real-time PCR primers were designed using Primer Express software (version 1.5; Applied Biosystems) from the RNA sequence, checked using BLAST (National Center for Biotechnology Information) and were purchased from Sigma (UK). The primer sequences for these analyses are presented in Additional file 2: Table S2. Real-time PCR was performed on a Lightcycler 480 (Roche, Burgess Hill, UK) using the 384 well format. Each reaction contained 5 μl of cDNA with the following reagents: 7.5 μl SYBR green master mix (Roche), 0.45 μl forward and reverse primers (final concentration 0.3 μM each) and 1.6 μl RNase-free H2O. Samples were pre-incubated at 95 C for 5 min followed by 45 PCR amplification cycles (de-naturation, 95 C for 10 s; annealing, 60 C for 15 s; elongation, 72 C for 15 s). Transcript abundance was determined using a standard curve generated from serial dilutions of a pool of cDNA made from all samples. Expression was normalised against the expression of cyclophilin, which was shown to be unaffected by maternal diet in the RNASeq analysis and subsequently by PCR. The primer sequences for these analyses are presented in Additional file 2: Table S2. Data from real-time PCR measurements was tested using independent samples t tests. Ten of the targets were shown to be differentially expressed in the protein restricted group, confirming the RNASeq analysis.

Results

The RNASeq analysis revealed differential expression of 91 genes in the day 13 rat placenta in response to maternal protein restriction. Of these, 24 were up-regulated and 67 were down-regulated. The full list of differentially expressed genes is provided in Table 1, and the full transcriptome analysis is available in Additional file 3: Table S3.

Analysis of the data set using ingenuity pathway analysis identified 19 pathways that were significantly affected by maternal protein restriction with P < 0.01. A more stringent cut-off of P < 0.001 identified eight significantly affected pathways (Table 2). The top six pathways (acute-phase response signalling, FXR/RXR activation, liver X receptor (LXR)/retinoid X receptor (RXR) activation, complement system, atherosclerosis signalling, clathrin-mediated endocytosis signalling) were closely related functionally, with a strong focus on cholesterol uptake and efflux across the placenta. Figure 1 shows heat maps for the genes involved in the functionally interesting enriched pathways. A relatively small number of genes contributed to the enrichment noted for all of these pathways (Ttr, ApoA2, ApoB, ApoC2, Fgg, Rbp4, Serpin A1, Serpin F2 and Serpin G1).

To validate the observations made using RNASeq analysis, quantitative real-time PCR was performed to explore the expression of 13 genes in two selection groups. The first group comprised genes that were differentially expressed with protein restriction and deemed functionally significant (associated with cholesterol transport) based upon the Ingenuity analysis (Ttr, ApoA2, ApoC2, Rbp4, Fgg, Actg2). The second group were genes that were differentially expressed but not associated with the pathways identified by Ingenuity (Muc13, Vil1, Gpc3, Cubn, Mttp). It should be noted that Cubn has a role in the uptake of high-density lipoprotein (HDL)-cholesterol by the placenta and that Mttp has a role in the packaging of cholesterol and lipid into low-density lipoprotein (LDL). Figures 2 and 3 show the data from the PCR analyses of these genes and Table 3 compares the fold-change in expression noted in the RNASeq analysis. The majority of genes in the validation set were strongly over-expressed in placentas from protein restricted pregnancies compared to controls, with a minimum of 4.53-fold (Gpc3) and maximum 41.35-fold (Fgg) up-regulation noted in this set. PCR analysis of three genes did not reproduce the statistically significant effects of protein restriction that were shown by RNASeq (Actg2, SerpinG1 and Prf1; Fig. 4). The PCR analysis generally detected a greater degree of up-regulation in the validation set than was noted with RNASeq (Table 3).

Expression of genes related to enriched pathways. Real-time qualitative PCR was used to validate the differential expression of seven genes related to canonical pathways identified by ingenuity as significantly influenced by maternal protein restriction. Expression was normalised to cyclophilin mRNA expression and *P < 0.05 between groups. n = 6 per group

Expression of genes unrelated to enriched pathways. Real-time qualitative PCR was used to validate the differential expression of six genes related to canonical pathways identified by ingenuity as significantly influenced by maternal protein restriction. Expression was normalised to cyclophilin mRNA expression. *P < 0.05 between groups. n = 6 per group

Discussion

In this experiment, we tested the hypothesis that maternal protein restriction would impact upon gene expression in the day-13 rat placenta. The data showed that this was in fact the case and that although the number of genes affected was small, the nutritional insult had a major impact upon expression of genes associated with cholesterol transport processes within the tissue. The expression of genes involved in the uptake of cholesterol by the placenta from HDL- LDL- and very low-density lipoprotein (VLDL)-cholesterol (ApoA2, ApoB, ApoC2, Cubn), the formation of clathrin-coated pits in which VLDL- and LDL-cholesterol receptors are located (Tf, Orm1, ApoA2, ApoC2, Actg2, Rbp4), the regulation of cholesterol efflux (Ttr, Tf, Orm1, Serpin F1, Rbp4, Mttp, Fgg, Serpin F2, Serpin A1) and the efflux from the placenta as LDL-cholesterol (ApoB, Mttp) were generally up-regulated by maternal undernutrition. Importantly, we have confirmed that the effects of maternal protein restriction during the first half of pregnancy may be mediated through changes in placental function.

Previous studies suggest that placental structure and organisation may be influenced by maternal protein restriction in both rats and mice [22–24]. These diet-related changes appear to be related to differential expression of adhesion molecules (beta catenin and vascular endothelial cadherin) and impaired cell proliferation. These processes appeared to be largely unaffected in the present study (although cadherin Cdh17 was down-regulated by protein restriction) and the discrepancies may stem from species differences or differences in stage of gestation at which samples were collected.

Functionally, placentas from protein-restricted rodents are known to differ in terms of materno-fetal steroid exchange [11] and transport of fatty acids and amino acids [12, 25, 26]. Whilst specific genes related to these functions have been previously identified as being sensitive to protein restriction, none were found to be differentially expressed in the current study. This is most likely explained by our study concentrating on day-13 rather than later stage placentas.

Cholesterol transport across the placenta is complex and involves a large number of proteins [27]. Cholesterol reaches the placenta in the form of LDL- VLDL- and HDL-cholesterol, which have ApoB, ApoC2 and ApoA2 respectively as their key structural proteins. LDL- and VLDL-cholesterol are taken up by their respective receptors which are located in clathrin-coated pits on trophoblasts. HDL-cholesterol can be taken up by SR-B1 (scavenger receptor class B member 1) or by binding to proteins such as megalin and cubilin. The latter two are multifunctional receptors which mediate uptake of material by endocytosis [28, 29]. Once taken up by trophoblasts, cholesterol is hydrolysed to cholesterol esters. Export from trophoblasts is in the form of either LDL-cholesterol or HDL-cholesterol. LDL-cholesterol is formed through placental expression of apoB and the action of microsomal triglyceride transfer protein (Mttp). HDL-cholesterol can be formed through complexing of lipids and cholesterol with a range of different apolipoproteins (ApoA1, ApoE, ApoA4, ApoC1, ApoC4; [27]). These are synthesised in response to LXR/RXR activation [30]. ApoA1 synthesis is also influenced by FXR/RXR activation [31]. Cholesterol efflux for formation of HDL-cholesterol complexes is dependent upon a range of ATP binding cassette proteins (AbcA1, AbcG1, AbcG5, AbcG8, [27]), which are downstream targets of FXR/RXR activation [32]. The present study has shown that almost all of these processes are sensitive to maternal protein restriction, and importantly, we have found that the only significant enrichment of pathways within our dataset lies in these processes. If there are any strong drivers of nutritional programming through the placenta at this stage of development, then cholesterol must play a key role.

The uptake of cholesterol by the embryo and fetus is critical for normal development [27], and defects of endogenous cholesterol synthesis are known to be lethal [33]. Cholesterol will also play an important role in placental function as it is the precursor for all steroid hormone synthesis. Disturbances of placental transport or endogenous fetal synthesis can have a number of effects on growth, cell proliferation, metabolism and the organisation of tissues [27, 34]. Low maternal cholesterol is associated with lower birth weight and microcephaly in humans [35], and women who have growth retarded infants have been found to have lower circulating cholesterol [36]. Optimal cholesterol transport to the fetus is therefore likely to have a positive impact upon development, and it is known that some of the effects are mediated through the cell cycle [37, 38]. However, some animal studies suggest that excessive cholesterol may also have a negative impact on growth. Bhasin et al. [39] reported that hypercholesterolaemia in pregnant LDL receptor knockout mice was associated with intrauterine growth retardation. The relationship between fetal cholesterol and the normal development and organisation of tissues may therefore be complex.

It is known that hypercholesterolaemia during pregnancy is associated with adverse health outcomes in the longer term. In humans, there is evidence that maternal hypercholesterolaemia is associated with the development of fatty streaks in fetal arteries [40], and cholestasis during pregnancy is associated with programming of an overweight, insulin-resistant phenotype in humans [41]. Animal studies have shown greater atherosclerosis in offspring of hypercholesterolaemic mothers [42, 43]. Previous work from our laboratory showed that in the ApoE*3 Leiden mouse, a transgenic rodent which has a predisposition to atherosclerosis, maternal protein restriction during fetal development increased atherosclerotic lesion size in adult life [44]. As atherosclerosis in this mouse is related to the degree of cholesterol exposure, it may be that intrauterine exposure to higher than normal cholesterol transport across the placenta may contribute to the adult disease phenotype. Induction of cholestasis using cholic acid in mouse pregnancy produces the same phenotype as in seen in humans [41] and is associated with greater cholesterol efflux from the placenta.

This study was an initial exploratory study to establish whether the placental transcriptome was significantly impacted by maternal protein restriction and to determine whether any observed effects were isolated to discrete processes within the tissue. One limitation of the study is that the whole placenta was used to generate the RNA, with no distinction between the maternal and fetal placental tissue. In the absence of any direct measurements of cholesterol transport or measurement of the genes of interest at the level of protein, assumptions are being made about the processes of cholesterol uptake and efflux being sensitive to maternal undernutrition. These measurements will be a priority for future studies, as will confirmation that placentas associated with female embryos respond in the same way as those from males.

Conclusions

Current thinking about the mechanisms which link maternal nutritional status and long-term health in offspring is largely focused upon lasting epigenetic changes within the fetal genome [45]. This study has highlighted placental function as being modulated by maternal undernutrition and reinforces the alternative concept that programming of fetal development and long-term health may be a product of dysregulation of nutrient transfer across the placenta. Further studies are needed to evaluate cholesterol transport across the placenta in protein-restricted pregnancies and to determine the impact of cholesterol on fetal gene expression, epigenetic regulation of gene expression and tissue morphology. This analysis of the placental transcriptome at the point where the placenta is not fully mature has supported the hypothesis that maternal undernutrition impacts upon placental function. The findings of this study will provide a platform for further investigation of processes within placenta that may be important new mechanistic targets or biomarkers that indicate nutritional programming of disease.

Abbreviations

- Actg2:

-

Actin G2

- Apo A4:

-

Apolipoprotein A4

- Apo B:

-

Apolipoprotein B

- ApoC2:

-

Apolipoprotein C2

- ApoE:

-

Apolipoprotein E

- CP:

-

Control protein

- Cubn:

-

Cublin

- Fgg:

-

Fibrinogen gamma chain

- FXR:

-

Farnesoid X receptor

- Gpc3:

-

Glypican 3

- HDL:

-

High-density lipoprotein

- Igf2:

-

Insulin-like growth factor 2

- LDL:

-

Low-density lipoprotein

- LP:

-

Low protein

- LXR:

-

Liver X receptor

- Mttp:

-

Microsomal triglyceride transfer protein

- Muc13:

-

Mucin 13

- PCR:

-

Polymerase chain reaction

- Prf1:

-

Perforin 1

- Rbp4:

-

Retinol binding protein 4

- RXR:

-

Retinoid X receptor

- Ttr:

-

Transthyretin

- Vil1:

-

Villin 1

- VLDL:

-

Very low-density lipoprotein

- Wnt2:

-

Wingless-type MMTV integration site family, member 2

References

Langley-Evans SC. Nutrition in early life and the programming of adult disease: a review. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2015;28 Suppl 1:1–14.

Barker DJ, Bull AR, Osmond C, Simmonds SJ. Fetal and placental size and risk of hypertension in adult life. BMJ. 1990;301:259–62.

Eriksson JG, Forsen TJ, Osmond C, Barker DJ. Pathways of infant and childhood growth that lead to type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:3006–10.

Hales CN, Barker DJ, Clark PM, Cox LJ, Fall C, Osmond C, Winter PD. Fetal and infant growth and impaired glucose tolerance at age 64. BMJ. 1991;303:1019–22.

Hoy WE, Hughson MD, Bertram JF, Douglas-Denton R, Amann K. Nephron number, hypertension, renal disease, and renal failure. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16:2557–64.

Langley-Evans SC, Welham SJ, Jackson AA. Fetal exposure to a maternal low protein diet impairs nephrogenesis and promotes hypertension in the rat. Life Sci. 1999;64:965–74.

Swali A, McMullen S, Hayes H, Gambling L, McArdle HJ, Langley-Evans SC. Cell cycle regulation and cytoskeletal remodelling are critical processes in the nutritional programming of embryonic development. PLoS One. 2011;6:e23189.

Swali A, McMullen S, Hayes H, Gambling L, McArdle HJ, Langley-Evans SC. Processes underlying the nutritional programming of embryonic development by iron deficiency in the rat. PLoS One. 2012;7:e48133.

Langley-Evans SC. Fetal programming of CVD and renal disease: animal models and mechanistic considerations. Proc Nutr Soc. 2013;72:317–25.

Burton GJ, Fowden AL. Review: the placenta and developmental programming: balancing fetal nutrient demands with maternal resource allocation. Placenta. 2012;33(Suppl):S23–27.

Langley-Evans SC, Phillips GJ, Benediktsson R, Gardner DS, Edwards CR, Jackson AA, Seckl JR. Protein intake in pregnancy, placental glucocorticoid metabolism and the programming of hypertension in the rat. Placenta. 1996;17:169–72.

Jansson N, Pettersson J, Haafiz A, Ericsson A, Palmberg I, Tranberg M, Ganapathy V, Powell TL, Jansson T. Down-regulation of placental transport of amino acids precedes the development of intrauterine growth restriction in rats fed a low protein diet. J Physiol. 2006;576:935–46.

de Rijk EP, van Esch E, Flik G. Pregnancy dating in the rat: placental morphology and maternal blood parameters. Toxicol Pathol. 2002;30:271–82.

Langley SC, Jackson AA. Increased systolic blood pressure in adult rats induced by fetal exposure to maternal low protein diets. Clin Sci (Lond). 1994;86:217–22.

Langley-Evans SC, Phillips GJ, Jackson AA. In utero exposure to maternal low protein diets induces hypertension in weanling rats, independently of maternal blood pressure changes. Clin Nutr. 1994;13:319–24.

Langley-Evans SC. Critical differences between two low protein diet protocols in the programming of hypertension in the rat. Int J Food Sci Nutr. 2000;51:11–7.

McMullen S, Langley-Evans SC (2005a) Maternal low-protein diet in rat pregnancy programs blood pressure through sex-specific mechanisms. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 288:R85-90

McMullen S, Langley-Evans SC (2005b) Sex-specific effects of prenatal low-protein and carbenoxolone exposure on renal angiotensin receptor expression in rats. Hypertension 46:1374-1380

Sugden MC, Holness MJ. Gender-specific programming of insulin secretion and action. J Endocrinol. 2002;75:757–67.

Trapnell C, Roberts A, Goff L, Pertea G, Kim D, Kelley DR, Pimentel H, Salzberg SL, Rinn JL, Pachter L. Differential gene and transcript expression analysis of RNA-seq experiments with TopHat and Cufflinks. Nat Protoc. 2012;7:562–78.

Trapnell C, Williams BA, Pertea G, Mortazavi A, Kwan G, van Baren MJ, Salzberg SL, Wold BJ, Pachter L. Transcript assembly and quantification by RNA-Seq reveals unannotated transcripts and isoform switching during cell differentiation. Nat Biotechnol. 2010;28:511–5.

Gao H, Yallampalli U, Yallampalli C. Gestational protein restriction affects trophoblast differentiation. Front Biosci. 2013;5:591–601.

Rebelato HJ, Esquisatto MA, de Sousa Righi EF, Catisti R. Gestational protein restriction alters cell proliferation in rat placenta. J Mol Histol. 2016;47:203–11.

Rutland CS, Latunde-Dada AO, Thorpe A, Plant R, Langley-Evans S, Leach L. Effect of gestational nutrition on vascular integrity in the murine placenta. Placenta. 2007;28:734–42.

Nüsken E, Gellhaus A, Kühnel E, Swoboda I, Wohlfarth M, Vohlen C, Schneider H, Dötsch J, Nüsken KD. Increased rat placental fatty acid, but decreased amino acid and glucose transporters potentially modify intrauterine programming. J Cell Biochem. 2016;117:1594–603.

Rosario FJ, Jansson N, Kanai Y, Prasad PD, Powell TL, Jansson T. Maternal protein restriction in the rat inhibits placental insulin, mTOR, and STAT3 signaling and down-regulates placental amino acid transporters. Endocrinology. 2011;152:1119–29.

Woollett LA. Review: transport of maternal cholesterol to the fetal circulation. Placenta. 2011;32 Suppl 2:S218–221.

Barth JL, Argraves WS. Cubilin and megalin: partners in lipoprotein and vitamin metabolism. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2001;11:26–31.

Willnow TE, Nykjaer A. Cellular uptake of steroid carrier proteins—mechanisms and implications. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2010;316:93–102.

Zhu R, Ou Z, Ruan X, Gong J. Role of liver X receptors in cholesterol efflux and inflammatory signaling (review). Mol Med Rep. 2012;5:895–900.

Claudel T, Sturm E, Duez H, Torra IP, Sirvent A, Kosykh V, Fruchart JC, Dallongeville J, Hum DW, Kuipers F, Staels B. Bile acid-activated nuclear receptor FXR suppresses apolipoprotein A-I transcription via a negative FXR response element. J Clin Invest. 2002;109:961–71.

de Aguiar Vallim TQ, Tarling EJ, Kim T, Civelek M, Baldán Á, Esau C, Edwards PA. MicroRNA-144 regulates hepatic ATP binding cassette transporter A1 and plasma high-density lipoprotein after activation of the nuclear receptor farnesoid X receptor. Circ Res. 2013;112:1602–12.

Porter FD. Human malformation syndromes due to inborn errors of cholesterol synthesis. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2003;15:607–13.

Haas D, Morgenthaler J, Lacbawan F, Long B, Runz H, Garbade SF, Zschocke J, Kelley RI, Okun JG, Hoffmann GF, Muenke M. Abnormal sterol metabolism in holoprosencephaly: studies in cultured lymphoblasts. J Med Genet. 2007;44:298–305.

Edison RJ, Berg K, Remaley A, Kelley R, Rotimi C, Stevenson RE, Muenke M. Adverse birth outcome among mothers with low serum cholesterol. Pediatrics. 2007;120:723–33.

Wadsack C, Tabano S, Maier A, Hiden U, Alvino G, Cozzi V, Huttinger M, Schneider WJ, Lang U, Cetin I, Desoye G. Intrauterine growth restriction (IUGR) is associated with alterations in placental lipoprotein receptors and maternal lipoprotein composition. Am J Physiol. 2007;292:E476–84.

Fernández C, Martín M, Gómez-Coronado D, Lasunción MA. Effects of distal cholesterol biosynthesis inhibitors on cell proliferation and cell cycle progression. J Lipid Res. 2005;46:920–9.

Singh P, Saxena R, Srinivas G, Pande G, Chattopadhyay A. Cholesterol biosynthesis and homeostasis in regulation of the cell cycle. PLoS One. 2013;8:e58833.

Bhasin KK, van Nas A, Martin LJ, Davis RC, Devaskar SU, Lusis AJ. Maternal low-protein diet or hypercholesterolemia reduces circulating essential amino acids and leads to intrauterine growth restriction. Diabetes. 2009;58:559–66.

Palinski W, Napoli C. The fetal origins of atherosclerosis: maternal hypercholesterolemia, and cholesterol-lowering or antioxidant treatment during pregnancy influence in utero programming and postnatal susceptibility to atherogenesis. FASEB J. 2002;16:1348–60.

Papacleovoulou G, Abu-Hayyeh S, Nikolopoulou E, Briz O, Owen BM, Nikolova V, Ovadia C, Huang X, Vaarasmaki M, Baumann M, Jansen E, Albrecht C, Jarvelin MR, Marin JJ, Knisely AS, Williamson C. Maternal cholestasis during pregnancy programs metabolic disease in offspring. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:3172–81.

Goharkhay N, Sbrana E, Gamble PK, Tamayo EH, Betancourt A, Villarreal K, Hankins GD, Saade GR, Longo M. Characterization of a murine model of fetal programming of atherosclerosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;197(416):e1–5.

Napoli C, de Nigris F, Welch JS, Calara FB, Stuart RO, Glass CK, Palinski W. Maternal hypercholesterolemia during pregnancy promotes early atherogenesis in LDL receptor-deficient mice and alters aortic gene expression determined by microarray. Circulation. 2002;105:1360–7.

Yates Z, Tarling EJ, Langley-Evans SC, Salter AM. Maternal undernutrition programmes atherosclerosis in the ApoE*3-Leiden mouse. Br J Nutr. 2009;101:1185–94.

Burdge GC, Lillycrop KA. Nutrition, epigenetics, and developmental plasticity: implications for understanding human disease. Annu Rev Nutr. 2010;30:315–39.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge Dr Sarah McMullen, Professor Harry McArdle and Dr Lorraine Gambling who contributed to the original experimental design for the animal experiment. Dr Samantha Ware performed analysis of the energy and protein content of the diets.

Funding

This work was supported by the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council [grant number BB/F005245/1], the Rosetrees Trust and the Stoneygate Trust.

Availability of data and materials

All RNASeq data has been provided as Additional file 3: Table S3 and is free to access and use in secondary analyses. Please acknowledge the authors in any future use.

Authors’ contributions

SLE designed the experiment and was responsible for data analysis. RE carried out bioinformatics analysis, AS performed the animal experiment and ZD was responsible for the preparation of samples for RNASeq and the PCR analyses. All authors contributed to the preparation of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Ethics approval

All animal work was performed under licence from the Home Office (UK) and complied with the Animals (Scientific Procedures) Act (1986). The project was approved by the University of Nottingham, Animal Ethics Committee.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional files

Additional file 1: Table S1.

Diets were prepared in our laboratory by mixing dry ingredients with the oil and then binding with water. The diets were then formed into balls which were dried at 60 °C for 24–48 h. Energy content of diets was determined by bomb calorimetry and protein content using a Flash Nitrogen analyser. (DOCX 22 kb)

Additional file 2: Table S2.

Primer sequences for quantitative real-time PCR. (DOCX 23 kb)

Additional file 3: Table S3.

Full transcriptome analysis. RNASeq data set, unedited. (XLS 6400 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

About this article

Cite this article

Daniel, Z., Swali, A., Emes, R. et al. The effect of maternal undernutrition on the rat placental transcriptome: protein restriction up-regulates cholesterol transport. Genes Nutr 11, 27 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12263-016-0541-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12263-016-0541-3