Abstract

Background

Extracranial internal carotid artery (ICA) pseudoaneurysm is a rare condition that can be caused either by penetrating or blunt trauma, including dog bites, which is an uncommon occurrence. Together with the possibility of no symptoms or nonspecific ones such as cervical pain, hematoma, swelling, or mass, considering ICA pseudoaneurysm following a dog attack is of paramount importance to avoid life-threatening complications.

Case presentation

We present a rare case of a 17-year-old male with a history of dog bites three months prior, who presented to the emergency department with left-sided neck pain, dizziness, and several episodes of blurred vision and diplopia. On physical examination, a palpable mass measuring approximately 20 × 30 millimeters was identified in the left neck region and multiple superficial lacerations were observed in this area. Laboratory tests yielded normal results. Doppler ultrasound revealed a pseudoaneurysm in the left internal carotid artery. Because the great saphenous veins were insufficient, the patient was successfully treated with synthetic graft patch arterioplasty, and no complications were seen in his one-year follow-up with computed tomography (CT) angiography.

Conclusions

This report emphasizes the significance of thorough initial evaluation and imaging in cases of dog attacks, even without apparent significant trauma, to rule out hidden arterial injuries.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Extracranial internal carotid artery (ICA) pseudoaneurysm is a rare condition that may be asymptomatic or present with cervical pain, hematoma, swelling, or masses. Patients with ICA pseudoaneurysm are prone to complications such as ruptures, hemorrhages, thromboembolic events, ischemic stroke, and cranial nerve dysfunction that overall increase the risk of morbidity and mortality [1]. ICA pseudoaneurysms are typically caused either by blunt or penetrating trauma, however, the animal bite is an uncommon cause of pseudoaneurysm, mostly seen in the radial or ulnar artery [2,3,4,5,6,7,8]. Dogs, particularly domestic ones, have the highest incidence rate of animal bites in Iran, approximately 10.4 per 1000 Iranians [9]. Most dog bite injuries typically happen in the head and neck area or limbs, usually superficial and requiring minimum medical intervention. However, dog bite injuries can be life-threatening while causing substantial tissue loss or affecting the airway and major arteries including the carotid artery [10]. In the literature, there are limited articles on relevant carotid injury from dog bites [2, 11,12,13,14,15]. To the best of our knowledge, this is the second report of internal carotid pseudoaneurysm following a dog bite, which highlights the importance of careful assessment of this danger concealed behind the innocuous wounds adjacent to the large vessels.

Case presentation

A 17-year-old male was admitted to the emergency department with left-sided neck pain and pulsatile mass, dizziness, and several episodes of blurred vision and diplopia. The patient reported being attacked by a dog and receiving a dog bite on his neck three months ago. The patient’s vital signs were stable upon arrival, and he was fully conscious. On examination, multiple bite-filled masses were observed on the patient’s face in the mandibular, temporal, left neck, and arm regions. A palpable mass measuring approximately 20 × 30 millimeters was identified in the left neck region (Fig. 1).

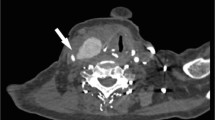

Laboratory tests yielded normal results, showing no evidence of leukocytosis, coagulopathy, or platelet disorders. All other laboratory investigations were within normal limits. The patient underwent a color Doppler ultrasound, which patient revealed a pseudoaneurysm at the left ICA near the site of bifurcation of the left carotid artery. A computed tomography (CT) scan was performed which demonstrated a focal outpouching of the left internal carotid artery, consistent with a posttraumatic left carotid pseudoaneurysm (Fig. 2).

Consequently, the patient was admitted for surgical intervention. During the procedure, exploration of the left carotid artery was performed and a shunt was inserted between the common carotid and internal carotid to save the blood flow. Because the great saphenous veins were insufficient in our exploration, carotid reconstruction was carried out using an expanded polytetrafluorethylene (ePTFE) patch angioplasty technique with prolene 7 − 0, followed by removal of shunt and hemostasis (Fig. 3).

Postoperatively, the patient was transferred to the ICU in a stable condition without complications. He remained conscious and able to communicate easily, with no hematoma observed at the surgical site. CT angiography was performed postoperatively and demonstrated normal findings with a proper blood supply to the repaired carotid artery. The patient had no complications during his one-year follow-up with CT angiography.

Discussion and conclusions

Extracranial ICA aneurysm is a potentially lethal condition with a rare entity, accounting for less than 1% of all arterial aneurysms. Pseudoaneurysms of the ICA are less prevalent than true aneurysms comprising 14% of all occurrences. The major cause of a pseudoaneurysm is either blunt or penetrating trauma. Traumatic causes of pseudoaneurysms vary from motor vehicle accidents, stab wounds, iatrogenic central venous cannulation or other cervical manipulations, sports accidents, and falls to animal bites [1]. A pseudoaneurysm after an animal bite is rare, with only 7 documented cases of this type of injury (Table 1) [2,3,4,5,6,7,8]. In the literature, animals responsible for pseudoaneurysms were snakes, cats, canines, and squirrels. Most of the pseudoaneurysms following animal bites occurred either in the radial or ulnar artery, while we report the second case of ICA pseudoaneurysm as a complication of a dog bite after the one by Miller et al. [2]. The reports of a pseudoaneurysm following animal bites were mostly from the USA, indicating that its true frequency may be considerably more than is currently recognized. This highlights the importance of widespread recognition and screening of this injury.

Carotid injury is an uncommon finding in case of a dog attack, with 6 reported cases, including carotid laceration, occlusion, dissection, and pseudoaneurysm formation (Table 2). Dog’s lick, scratch, or bite may also be infected with Pasteurella multocida, resulting in mycotic aneurysm [6]. Serious dog bite injuries not only lead to lacerations on the skin but also can cause considerable damage to soft tissue by crushing, grinding, and avulsion [2]. Damage to the arterial wall, resulting in local hematoma. Maintained turbulent blood flow between the arterial laceration and the hematoma results in pseudoaneurysm development [16, 17].

Up to 60% of extracranial ICA pseudoaneurysm cases may be asymptomatic, similar to our patient at his first admission. As in our case, the enlarging pseudoaneurysm may present with pain and a pulsating neck mass. Other presentations include a medial bulge in the pharyngeal wall, or as carotid thrill or bruit, cranial nerve palsies, and ruptures with hemorrhage. Pseudoaneurysm can also be accompanied by thrombosis, leading to a cerebral infarction [1, 2]. Similar to our patient, the ophthalmological symptoms have been reported in some cases of ICA pseudoaneurysm, including amaurosis or low visual acuity and blurred vision. These symptoms usually occur unilaterally and may be related to the impairment of the blood supply. Bilateral involvement can also be seen regarding the anatomical anastomosis of cavernous sinuses [16].

The proper management of dog bite wounds involves thorough cleaning of the wound with debridement, primary repair, antibiotic therapy, and rabies vaccination if necessary. When assessing a dog attack, even without major penetrating trauma as in our case, additional assessment should also be done to prompt rule out hidden arterial injury such as pseudoaneurysm affected by the blunt force of the attack, which could otherwise be delayed and lead to morbidity and mortality [18].

A pseudoaneurysm can be presented either in an acute or delayed fashion. The time to diagnosis of a pseudoaneurysm was different in the cases of animal bites, ranging from a few hours to three weeks (Table 1). In contrast to Miller et al.’s study, our patient was diagnosed with carotid pseudoaneurysm three months after the dog attack with color Doppler sonography. At the initial evaluation of our case, no signs or symptoms were detected supportive of pseudoaneurysm, which highlights the importance of imaging modalities. Considering to be the first-line imaging modality, sonography is an accessible and cost-effective method to prompt the diagnosis of trauma-induced pseudoaneurysms of the extracranial carotid artery, even in the case of a delayed diagnosis similar to our patient. However, CT angiography can be a better choice for distal carotid artery pseudoaneurysm [19, 20]. Contrast-enhanced CT and magnetic resonance imaging can also assist in diagnosing pseudoaneurysm [1].

Surgical procedures, endovascular or open repair, may vary depending on the specific characteristics of each severe bite lesion. The gold standard of treatment is complete excision of the pseudoaneurysm while intersecting the gap with synthetic or saphenous vein grafts or end-to-end anastomosis [1]. Regarding its high long-term potency, the open repair technique has been suggested in young cases of extracranial carotid pseudoaneurysms with accessible lesions and low surgical risk [20]. In this accordance, we performed a patch angioplasty of the carotid with an ePTFE graft. It should be noted that long-term surveillance imaging with a vascular surgeon will be required in repairs involving the implantation of stent/graft devices [17]. Based on our one-year follow-up with CT angiography, ePTFE grafts can be effective for the treatment of ICA pseudoaneurysms.

In conclusion, pseudoaneurysm of ICA as a complication of a dog bite has not been reported in the literature over the past twenty years. Regarding the rarity of involved deep neck structures as a result of animal bites and also the possible latency of symptoms, it seems important for clinicians to consider evaluation of these injuries at initial care and warn patients of such life-threatening complications to reach for early medical care in case of any signs or symptoms.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Abbreviations

- ICA:

-

Internal carotid artery

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- ePTFE:

-

Expanded polytetrafluorethylene

References

Ong JL, Jalaludin S. Traumatic pseudoaneurysm of right Extracranial Internal Carotid artery: a rare entity and recent Advancement of treatment with minimally invasive technique. Malays J Med Sci. 2016;23(2):78–81.

Miller SJ, Copass M, Johansen K, Winn HR. Stroke following rottweiler attack. Ann Emerg Med. 1993;22(2):262–4.

Levis JT, Garmel GM. Radial artery pseudoaneurysm formation after cat bite to the wrist. Ann Emerg Med. 2008;51(5):668–70.

Dryton G, Allen KB, Borkon AM, Aggarwal S, Davis JR. Do not bite the hand that feeds you. Ann Vasc Surg. 2015;29(2):e3623–4.

Pin L, Lutao X, Weijun F, Feng P, Chaohui C, Jianrong W. Ulnar artery pseudoaneurysm and compartment syndrome formation after snake bite to the left forearm. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2018;56(6):436–8.

Jeng EI, Acosta G, Martin TD, Upchurch GR. Jr. Pasteurella Multiocida infection resulting in a descending thoracic aorta mycotic pseudoaneurysm. J Card Surg. 2020;35(8):2070–2.

Senthilkumaran S, Miller SW, Williams HF, Vaiyapuri R, Savania R, Elangovan N et al. Ultrasound-Guided Compression Method Effectively Counteracts Russell’s Viper Bite-Induced Pseudoaneurysm. Toxins (Basel). 2022;14(4).

Winter L, Chaudhry T, Wilson JL, Walker J, Huang D. Radial artery pseudoaneurysm from a Squirrel Bite. Cureus. 2023;15(9):e46080.

Abedi M, Doosti-Irani A, Jahanbakhsh F, Sahebkar A. Epidemiology of animal bite in Iran during a 20-year period (1993–2013): a meta-analysis. Trop Med Health. 2019;47:1–13.

Bathula SS, Mahoney R, Kerns A, Minutello K, Stern N. Combined pharyngeal laceration and laryngeal fracture secondary to dog bite: a case report. Cureus. 2020;12(10).

Itoyama Y, Fujioka S, Takaki S, Kimura H, Hide T, Ushio Y. [Occlusion of the cervical internal carotid artery due to a dog bite wound: case report]. No Shinkei Geka. 1994;22(4):353–6.

Meuli M, Glarner H. Delayed cerebral infarction after dog bites: case report. J Trauma. 1994;37(5):848–9.

Endean ED, Kirbo B. Carotid artery occlusion after dog bite. J Ky Med Assoc. 1995;93(10):456–8.

Varela JE, Dolich MO, Fernandez LA, Kane A, Henry R, Livingston J, et al. Combined carotid artery injury and laryngeal fracture secondary to dog bite: case report. Am Surg. 2000;66(11):1016–9.

Cheng CL, Chiang LC, Ho CH, Liu PY, Lai CS, Lai KL et al. Ulnar artery pseudoaneurysm and compartment syndrome formation after snake bite to the left forearm by Lan Pin Clin Toxicol (Phila) 2017 Nov. 10. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2018;56(7):676-7.

Pinto PS, Viana RS, de Souza RRL, Monteiro J, Carneiro S. Pseudoaneurysm of the Internal Carotid Artery after Craniofacial Traumatism: series of cases and Integrative Literature Review. Craniomaxillofac Trauma Reconstr. 2021;14(4):330–6.

Rivera PA, Dattilo JB. Pseudoaneurysm. 2019.

Calkins CM, Bensard DD, Partrick DA, Karrer FM. Life-threatening dog attacks: a devastating combination of penetrating and blunt injuries. J Pediatr Surg. 2001;36(8):1115–7.

Hill DS, Hill J. Unsuspected traumatic pseudoaneurysm of the internal carotid artery. J Diagn Med Sonography. 2015;31(6):372–6.

Vaddavalli VV, Savlania A, Abuji K, Kaman L, Behera A. Surgical Management and Clinical outcomes of Extracranial Carotid Artery pseudoaneurysms. Permanente J. 2024:1–6.

Acknowledgements

None to declare.

Funding

No financial support was received for this case report.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

AH designed the study. FD and HA collected the data and performed a review of the literature. FZ drafted the manuscript and RS critically revised the manuscript. All authors proofread and accepted the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient in our study. The purpose of this research was completely explained to the patient and was assured that their information will be kept confidential by the researcher. The present study was approved by the Medical Ethics Committee of the Shiraz University of Medical Sciences and performed in accordance with the ethical standards as laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Consent for publication

Consent was obtained from the patient regarding the publication of this case report.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hosseinzadeh, A., Shahriarirad, R., Dalfardi, F. et al. An unsuspected extracranial internal carotid pseudoaneurysm following dog bites: a case report and review of literature. Int J Emerg Med 17, 108 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12245-024-00688-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12245-024-00688-0