Abstract

Tungsten (W) was coated onto a silicon (Si) anode at the nanoscale via the physical vaporization deposition method (PVD) to enhance its electrochemical properties. The characteristics of the electrode were identified by scanning electron microscopy (SEM), transmission electron microscopy (TEM), energy dispersive X-ray analysis, and electron probe X-ray microanalysis. With the electrochemical property analysis, the first charge capacities of the W-coated and uncoated electrode cells were 2558 mAh g− 1 and 1912 mAh g− 1, respectively. By the 50th cycle, the capacity ratios were 61.1 and 25.5%, respectively. Morphology changes in the W-coated Si anode during cycling were observed using SEM and TEM, and electrochemical characteristics were examined through impedance analysis. Owing to its conductivity and mechanical properties from the atomic W layer coating through PVD, the electrode improved its cyclability and preserved its structure from volumetric demolition.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Silicon (Si) is one of the most attractive energy source elements that can be used as an anode because of its high-specific capacity (4200 mAh g− 1), which is 10 times higher than that of graphite [1]. However, Si experiences problematic volumetric expansion during charging and discharging processes, and the expansion causes a 300% change in lattice volume [2,3,4,5]. This results in cracking and disintegration of the electrode, leading to active material loss, a decrease in electrical contact, and eventual degradation of electrical properties. Additionally, the low electrical conductivity of Si is a barrier to its use as an electrode material.

Therefore, methods for improving the electrochemical properties of Si electrodes are of high interest, and extensive research has been conducted to solve the problems associated with the Si electrode, such as using electrodes with a carbon (C) composite composition, multidimensional structures, and metal-alloyed forms [6,7,8,9,10,11,12]. In particular, for active material methods used in shockproofing, many studies have pursued approaches for coating the subject with various materials [13,14,15,16]. Conductive materials such as carbon, metal alloys, and even conductive polymers have been employed to restrain the expansion effect, and they have provided not only a buffering effect but also charge transportation enhancement. However, these research methods have limitations regarding their use in commercial applications because of their detailed fabrication procedures.

Physical vaporization deposition (PVD) produces a uniform coating on a substrate at the nanometer to visible scale through the process of atomic deposition [17,18,19,20]. This versatile technique can be applied in various fields to enable the deposition of every inorganic material type and even some organic materials. Additionally, because this method induces less resistance than chemical deposition with a tight layer formed by heterogeneous nucleation and growth [21], mechanical properties such as wear resistance and hardness are improved greatly.

In this study, a Si electrode was coated with tungsten (W) using the PVD method to provide a buffer layer and increase its conductivity. Among all metals in pure form, W has the highest tensile strength and superior hardness [22, 23]. In addition, Hornik et al. [24] studied the effect of W PVD by magnetron sputtering on ceramic substrates and showed that the W coating can function suitably for substrates with low hardness or wear resistance. By applying a W nanolayer to the electrode surface, the electrochemical properties and morphologies of the Si electrode were examined using various analytical techniques. This W nanolayer application showed improved electrochemical properties and sustained structural safety.

Experimental

Fabrication of Electrodes

Si electrodes were fabricated using a casting method with 40 wt% Si nanopowder (≤ 100 nm), 40 wt% Denka Black as a conductive material, and carboxymethyl cellulose as a binder. These substances were dissolved in deionized water to form a slurry. The slurry was then coated onto a piece of copper foil (50 μm) and dried at 70 °C for 1 h. The W coating of the Si electrode was conducted using the PVD method (Fig. 1) at Dongwoo Surface Tech Co., Ltd. Ar gas was used as the plasma generator at 100 °C, and W deposition was conducted for 5 min. The deposited W electrode surface was examined by scanning electron microscopy (SEM), transmission electron microscopy (TEM), electron probe X-ray microanalysis (EPMA), and energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX).

Test Cell Procedure

The test cell was assembled with a CR2032-type coin cell in a dry room. The Si anode electrodes were punched out to a size of 14Φ, and the counter electrodes were punched from lithium foil to a size of 16Φ. The measured weight of W nanolayer corresponding to a 14Φ-sized electrode is approximately 0.0001 g. The electrolyte used was 1 M LiPF6 with a mixture comprising equal volumes of ethylene carbonate, dimethyl carbonate, and ethylene methyl carbonate (Soulbrain, Republic of Korea). All cells were fabricated in a dry room. The assembled cell was aged for 24 h at 40 °C.

Galvanostatic electrochemical tests were performed using a WBCS 3000 instrument (WonATech Inc., Republic of Korea). Charging and discharging processes were performed between 0 and 1.5 V with specific current rates for each process. After the cycles, surface observations of W-coated and uncoated Si electrodes were conducted. Additionally, impedance tests were performed at frequencies of 10− 2 to 105 Hz with an AC amplitude of 5 mV (SOLATRON SI1280B) to compare the coating effect.

Results and Discussion

Figure 2 shows SEM images of pristine uncoated (a) and W-coated (b) Si electrodes. Because the electrode consisted of Si nanopowder with a size less than 100 nm, the powder retained its original size. However, owing to the physical deposition of W onto the coated electrode, each particle seemed to be covered with a W layer, and the overall size of the particles increased to approximately 100 to 120 nm. EDX analysis of the elements in the red box of the SEM image (Fig. 2b) revealed the presence of W (Fig. 2d). Additionally, EPMA confirmed that the deposited W was uniformly distributed (Fig. 3).

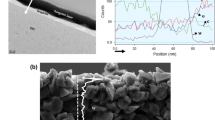

TEM analysis with depth profiling was conducted to examine the thickness of the W layer. Figure 4 confirms that the W layer (white) deposited onto the Si nanoparticles (black) had a depth of approximately 40 nm. The W layer also covered the gaps between Si powder and other electrode materials. From the above tests, it is apparent that the W layer coated via the PVD method was well formed at the nanometer scale .

An electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) test was performed for further analysis. Figure 5 shows the impedance results for (a) the uncoated Si and W-coated Si electrodes and (b) the equivalent circuit. The figure shows the equivalent circuit based on the Randles circuit structure, and Table 1 lists the results of impedance fitting. In the equivalent circuit, Rs indicates the sum of the ohmic resistances of the electrode and electrolyte, and Rct and Cdl represent the charge transfer resistance and double-layer capacitance, respectively. The constant phase element (CPE) is connected to Rct in series [25, 26]. Rsei and Csei, which are related with the resistance and capacitance of the electrode surface [27], are in parallel.

By comparing the initial states, as shown in Fig. 5 and Table 1, the values of Rs and Rct decreased owing to the W coating, whereas Rsei increased because of the increase in surface resistance. This result indicates that, because of the uniform coating of the W layer, the electrical conductivity was enhanced, which may contribute to increased capacity and stable cyclability. However, the increases in Rsei and ion diffusion impedance are also observed, implying that the W layer can act as an ion permeability inhibiter.

The specific capacities of the bare and W-coated cells at a rate of 0.1 C over 50 cycles are plotted in Fig. 6. For the first cycle, the charge capacities of the W-coated and uncoated Si electrode cells were 2588 and 1912 mAh g− 1, respectively. This may be explained by the high electrical conductivity of W, which allows the Si electrode to receive more Li ions and stimulates faster charge transfer. The discharge capacities of the W-coated Si electrode at the 10th, 20th, and 50th cycles were 1843, 1676, and 1137 mAh g− 1, respectively, and the retention ratios of the same cycles were 99.1, 90.1, and 61.1%, respectively. Those values for the uncoated Si electrode were 1132, 790, and 452 mAh g− 1 and 63.9, 44.6, and 25.5%, respectively. The coated cell clearly showed improved capabilities. This result is attributable to the W coating, which forms a buffer layer and enhances electrical conductivity. The uncoated Si electrode was exposed to structural destruction, while the W-coated Si electrode was protected by the W nanolayer, preventing the formation of cracks overall and leading to the conservation of the electrode surface. However, the W coating induced irreversible capacity loss during every cycle. Because Li ions must travel through the inactive W layer, which is not an ion-conductive material as discussed in the EIS test, the ion transport during discharging might be sluggish, resulting in irreversibility.

Figure 7 shows the dQ/dV curves of the 5th, 10th, and 15th cycles for both the W-coated and uncoated Si electrodes. The reaction peaks are in the same voltage regions, which imply that the charging and discharging processes occurred with the equivalent reaction [28, 29]. This indicates that the W coating did not influence the morphology of the Si electrode but covered only the surface layer, and it did not act as an active material. As the cycle number increased, the reaction voltage region of the uncoated Si electrode shifted and the polarization increased, whereas the reaction voltage region of the W-coated Si electrode remained relatively constant. This implies that the W coating helps retain chemical stability. This result is also reflected in the voltage profile in Fig. 8, which shows the W-coated electrode preserves its capacity with sustained reaction voltages.

Both the W-coated and uncoated Si electrodes were observed by SEM after 10 cycles (Fig. 9). No cracks were observed on the Si electrode itself, using nanopowder sizes smaller than 100 nm [30]. However, a split occurred during the cycles owing to expansion of the entire electrode. Nevertheless, the W-coated Si electrode remained uncracked, indicating that the atomic deposition by PVD and the intense mechanical strength of W effectively sustained the expansion [19, 20].

Conclusions

W was coated onto a Si electrode using the PVD procedure to improve the electrochemical performance of the electrode. The coating layer was approximately 40-nm thick and was deposited uniformly. The capacity retention of the W-coated electrode demonstrated enhanced cyclability and was sustained at 61.1% through 50 cycles, whereas the retention of the uncoated electrode was only 25.5%. The surfaces of the two different electrodes were investigated after cycling, and the observations indicated that W acted as a buffer layer. Additionally, the W-coated layer lowered the resistivity of the electrode and enhanced the electrical conductivity of the cell. We hope that this facile nanolayer application through PVD can serve as a reference for future designs of Si-based electrodes.

Abbreviations

- CPE:

-

Constant phase element

- EDX:

-

Energy dispersive X-ray spectroscopy

- EIS:

-

Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy

- EPMA:

-

Electron probe X-ray microanalysis

- PVD:

-

Physical vaporization deposition

- SEM:

-

Scanning electron microscopy

- TEM:

-

Transmission electron microscopy

References

Obrovac MN, Christensen L (2004) Structural changes in silicon anodes during lithium insertion/extraction. Electrochem Solid State Lett 7(5):A93–A96.

Chan CK, Peng H, Liu G, McIlwrath K, Zhang XF, Huggins RA, Cui Y (2008) High-performance lithium battery anodes using silicon nanowires. Nat Nanotechnol 3(1):31–35.

Ogata K, Salager E, Kerr CJ, Fraser AE, Ducati C, Morris AJ, Hofmann S, Grey CP. Revealing lithium–silicide phase transformations in nano-structured silicon-based lithium ion batteries via in situ NMR spectroscopy. Nat Commun. 2014;5:3217.

Lee YM, Lee JY, Shim HT, Lee JK, Park JK (2007) SEI layer formation on amorphous Si thin electrode during precycling. J Electrochem Soc 154(6):A515–A519.

Winter M, Besenhard JO (1999) Electrochemical lithiation of tin and tin-based intermetallics and composites. Electrochim Acta 45(1):31–50.

Wong DP, Tseng HP, Chen YT, Hwang BJ, Chen LC, Chen KH (2013) A stable silicon/graphene composite using solvent exchange method as anode material for lithium ion batteries. Carbon 63:397–403.

Wei Y, Yu H, Li H, Ming H, Pan K, Huang H, Liu Y, Kang Z (2013) Liquid-phase plasma synthesis of silicon quantum dots embedded in carbon matrix for lithium battery anodes. Mater Res Bull 48(10):4072–4077.

Ishihara T, Nakasu M, Yoshio M, Nishiguchi H, Takita Y (2005) Carbon nanotube coating silicon doped with Cr as a high capacity anode. J Power Sources 146(1):161–165.

Chen H, Xiao Y, Wang L, Yang Y (2011) Silicon nanowires coated with copper layer as anode materials for lithium-ion batteries. J Power Sources 196(16):6657–6662.

Kim H, Han B, Choo J, Cho J (2008) Three-dimensional porous silicon particles for use in high-performance lithium secondary batteries 2008. Angew Chem 120(52):10305–10308.

Chen W, Jiang N, Fan Z, Dhanabalan A, Chen C, Li Y, Yang M, Wang C (2012) Facile synthesis of silicon films by photosintering as anode materials for lithium-ion batteries 2012. J Power Sources 214:21–27.

Zhongsheng WEN, Shijun JI, Juncai SUN, Feng TIAN, Rujin TIAN, Jingying XIE (2006) Mechanism of lithium insertion into NiSi2 anode material for lithium ion batteries. Rare Metals 25(6):77–81.

Cui LF, Yang Y, Hsu CM, Cui Y (2009) Carbon––silicon core––shell nanowires as high capacity electrode for lithium ion batteries. Nano Lett 9(9):3370–3374.

Dimov N, Kugino S, Yoshio M (2003) Carbon-coated silicon as anode material for lithium ion batteries: advantages and limitations. Electrochim Acta 48(11):1579–1587.

He Y, Yu X, Wang Y, Li H, Huang X (2011) Alumina-coated patterned amorphous silicon as the anode for a lithium-ion battery with high Coulombic efficiency. Adv Mater 23(42):4938–4941.

Guo ZP, Wang JZ, Liu HK, Dou SX (2005) Study of silicon/polypyrrole composite as anode materials for Li-ion batteries. J Power Sources 146(1):448–451.

Dixit S, Popat PP, Rawat SS, Sivarajan S (2016) Multilayer PVD surface engineered coatings for sheet metal forming tools. Indian J SciTechnol 9(41).

Malarvannan R, Moorthy TV, Hariharan P, Ravi S (2015) Enhancement of wear properties on high speed steel tool using PVD coating technique. Appl Mech & Mater 812:107–111.

Sun P, Ma Y, Zhai T, Li H (2016) High performance LiNi 0.5 Mn 1.5 O 4 cathode by Al-coating and Al 3+––doping through a physical vapor deposition method. Electrochim Acta 191:237–246.

Bae KY, Lim CW, Cho SH, Kim BH, Yoon WY (2016) Tungsten carbide-coated LiV3O8 cathodes with enhanced electrochemical properties for lithium metal batteries. Nanosci Nanotechnol 16(10):10613–10619.

Lee JW, Kim JK, Kim SH, Sun HJ, Yang HS, Sohn HC, Kim JW (2004) Physical and electrical characteristics of physical vapor-deposited tungsten for bit line process. Jpn J Appl Phys 43(12R):8007.

Sun HL, Song ZX, Guo DG, Ma F, Xu KW (2010) Microstructure and mechanical properties of nanocrystalline tungsten thin films. J Mater Sci Technol 26(1):87–92.

Lassner E, Schubert WD. Tungsten: properties, chemistry, technology of the element, alloys, and chemical compounds. Springer Science & Business Media; 1999.

Horník J, Tondl D, Sachr P, Anisimov E, Puchnin M, Chraska T (2014) The effect of PVD tungsten-based coatings on improvement of hardness and wear resistance. Key Eng Mater 606:163–166.

Shiraishi S, Kanamura K, Takehara ZI (1999) Surface condition changes in lithium metal deposited in nonaqueous electrolyte containing HF by dissolution-deposition cycles. J Electrochem Soc 146(5):1633–1639.

Jamnik J, Maier J (2003) Nanocrystallinity effects in lithium battery materials aspects of nano-ionics. J Phys Chem Chem Phys 5(23):5215–5220.

Lee KH, Song SW (2011) One-step hydrothermal synthesis of mesoporous anatase TiO2 microsphere and interfacial control for enhanced lithium storage performance. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces 3(9):3697–3703.

Wu H, Cui Y (2012) Designing nanostructured Si anodes for high energy lithium ion batteries. Nano Today 7(5):414–429.

Kasavajjula U, Wang C, Appleby AJ (2007) Nano-and bulk-silicon-based insertion anodes for lithium-ion secondary cells. J Power Sources 163(2):1003–1039.

Ye JC, An YH, Heo TW, Biener MM, Nikolic RJ, Tang M, Jiang H, Wang YM (2014) Enhanced lithiation and fracture behavior of silicon mesoscale pillars via atomic layer coatings and geometry design. J Power Sources 248:47–456.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable

Funding

This research was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Korean government (MEST) (2016R1A2B3009481 and 2017M3A9E2093907).

Availability of Data and Materials

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

BDS and JKL were involved in preparing materials. BDS fabricated and characterized the electrodes. BDS designed and modified the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Author’s Information

Not applicable

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Son, B.D., Lee, J.K. & Yoon, W.Y. Effect of Tungsten Nanolayer Coating on Si Electrode in Lithium-ion Battery. Nanoscale Res Lett 13, 58 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s11671-018-2460-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s11671-018-2460-2