Abstract

Mechanisms of the formation of nanoparticles of some B2 shape memory intermetallic compounds, glass-forming Zr-based alloy, and pure Ti obtained by spark erosion method in liquid nitrogen and argon are considered. One of peculiarity is a foam-like structure, which covers the surface of micron-sized particles that appear during spark erosion. Such morphology is related to the nanosized particles gathered in agglomerates. Detailed examination of those particles allows proposed several mechanisms of their formation. The mechanisms explains two kinds of nanosized particles: particles of several tens and even hundreds of nanometers are formed due to explosion of molten droplets while the smaller particles having in turn a different structure and morphology are formed as a result of condensation of evaporated constituents under different conditions. The latter have the composition usually different from the target composition while the composition of the former is very close to the target (master alloy) composition.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Background

Shape memory materials (Ti-Ni-based, Ni-Mn-Ga, Ni-Al, Cu-Al-Ni) and high-temperature shape memory materials (Ti-Ni-Hf, Ti-Ni-Zr) have attractive perspectives for practical application with the use of the nanostructures of various kinds in particularly. Their operation is closely connected with the fundamental problem of martensitic transformation in nanoscale objects like nanoparticles. Unfortunately, there is no universal method to obtain nanosized particles from the pre-alloying materials with target composition—the mandatory condition for their practical using.

The well-known method of gas or liquid atomization [1–3] is not suitable for the production of a significant amount of fine powder with particle sizes less than several microns. The yield of powder submicron- and nanosized alloys particles is considerably higher in mechanical alloying method [3–6]. The drawback of this method is that there is a significant level of contaminants or additional phases that appear in the powder, which is prepared from elemental materials. The advantages of the wire explosion method [7, 8], which yields particularly dispersed powders, are often frustrated by the high cost of equipment, energy consumption, and the small number of the powder obtained. Chemical synthesis approach successfully used for Au-Cd nanoparticles production [9] is heuristic by definition. In this work, we will focus on spark erosion method. The method allows obtaining alloy powder with a given chemical composition in a wide range of sizes, with a relatively low level of contaminants [10–32]. One of the features of this method is the foam-like structures, which coat the surface of micron-sized particles that appear during spark erosion [27–32].

Mostly, the interest given to the spark erosion powder is caused by the micron-sized particles, the finest of them are removed by washing. At the same time, the detailed examination of the structure of such particles can help to highlight the mechanism of spark erosion powder formation mechanism as was shown in [27, 31, 32]. The goal of this article is to classify the experimental results, which are able to clarify the possible mechanisms of nanoparticle formation.

Methods

The general principle of spark erosion processing was described in details in [10, 12, 25, 26]. It involves the application of a heavy current between two electrodes and a lot of small pieces sized 3–5 mm prepared from the pre-alloyed material, both being immersed in a dielectric coolant inside a container (liquid argon or liquid nitrogen). The key idea of the method is to apply the heavy electrical current of an electric discharge with a duration of 5–100 μs between the electrodes. Many sparks (arcs) simultaneously appear between the granules of the materials forming many conductive channels between the electrodes. When the spark collapses, molten droplets are ejected from these boiling regions with subsequent quenching in situ into coolant liquid (Fig. 1). Then, the powders are kept in a vessel with cryogenic liquid during the day until all liquid evaporated followed by passivation in hexane in order to prevent eventual explosion of the finest particles of the powders.

Principal scheme of the spark erosion working chamber. A similar chamber was used for the powder elaboration [26]. Round inset shows the formation during the spark discharge between the granules (1) the molten droplets, (2) the evaporated constituents of material, and (3) the irregular broken fragments of material pieces

Pure Ti as well as Ni49.0Mn28.5Ga22.5, Cu67.9Al27.5Ni3.8Ti0.5Cr0.3, Ni61.9Al38.1, Ni49Cu1Ti47Zr3, Ni49.9Ti40.3Zr0.3Cu0.1Hf9.4, and Zr57Cu20Al10Ni8Ti5 alloys were used for powder preparation. Ni-Mn-Ga, Ti-Ni-Zr, and Ti-Ni-Hf alloys were prepared by induction melting while Ni-Al and Zr-Cu-Al-Ni-Ti by arc melting. Ti-Ni-based alloys were subjected to hot rolling followed by homogenization before spark erosion processing while the other ones were subjected only homogenization because of their brittleness. More details of the alloy and spark erosion powder production can be found in [27–32].

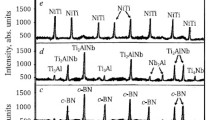

X-ray diffraction (XRD) and scanning electron microscopy (SEM) studies were carried out to reveal the crystal structure and morphology of the powders as a whole. The morphology, composition, and fine structure of the nanosized particles were investigated by different methods of analytical transmission electron microscopy (TEM), including high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM), energy-filtered transmission electron microscopy (EFTEM), and energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) analysis. For the sample preparation, the finest fraction of powders was mixed with ethanol; the mixture was dropped onto a copper grid covered by a carbon film. After evaporation of the ethanol, the sample was placed in the column of the microscope. A detailed description of the methods of structural investigations is provided in [27, 28, 31, 32].

Results and Discussion

Morphology of Spark Erosion Powders

It is considered that there are three main mechanisms of the powder particle formation: (a) mechanical breaking, (b) quenching from a liquid state, and (c) condensation from vapor states [29]. The morphology of the powder particles indirectly proves the mechanisms of the powder particle formation [28]. The shape of the largest particles (more than 30 ÷ 50 μm depending on the alloy) is mostly irregular confirming its origin due to mechanical shocks. The particles with dimensions less than 30–50 μm have a spherical shape (Fig. 2a). The part of such particles in the powder is close to 70 ÷ 90 % dependently on the alloys [27, 29, 31]. They are formed due to rapid quenching into coolant liquid. Hereinafter, we are concentrating on the particle sizes of several tens of nanometers (sometimes hundreds as shown on Fig. 2b). Most of such kind of particles are gathered in agglomerates (Fig. 2c).

In the first glance, there is no great difference between the morphologies of the powders formed due to the quenching into the coolant liquid or condensation from the vapor state (Fig. 2a–c). However, two main evidence forces us to make the difference. Firstly, SEM studies reveal that solidified molten droplets usually appear on images as the separated spherical particles with a well distinguishing surface (Fig. 3a). In most cases, the foam-like shell that formed from the nanosized particles coats the surface of micron-sized particles (Fig. 3b). Secondly, there is a large difference between the particle size distributions of the micron-sized and nanosized particles. For the former, the maximum volume size distribution is located near 25–50 μm dependently on the alloy compositions and parameters of spark erosion processing while for the latter, most of the particles have sizes less than several tens nanometers. At the same time, the particle sizes of several hundreds nanometers arise sporadically. These facts allow us to suppose that the different mechanisms are responsible for the formation of micron- and nanosized particles.

Nanosized Particles

TEM investigation revealed that the finest particles with a dimension down to 5 nm have a trend to form agglomerates (Figs. 4, 5, 6, 7, and 8). The prevailing particle morphology is spherical although sometimes it is very difficult to clearly recognize the shape of the smallest particles assembled in chains or agglomerates. In addition, in Ti powders obtained in liquid nitrogen, the cuboids were found here and there [27], which is typical for ultrafine δ-TiN x particles [33] (Fig. 4). Most of the particles have size below 40 nm; however, the spherical particle sizes of ~100 ÷ 1000 nm appear on TEM images occasionally (Figs. 2b, 4b, 5a, 8a).

Particles of Ni46.7Ti49.2Zr3.41Cu0.8 powder in a martensitic state (B19′ structure). a Dark-field image (from (011) spot) of an 80-nm particle having a distinct internal structure and embedded in agglomerates of nickel and titanium oxides. b Bright-field image of the hollow particle with a diameter of 1 μm

The electron diffraction taken from the agglomerates consists of diffuse rings related obviously to the finest particles and distinct spots related to the strictly crystalline structure of the largest particles (inset of Fig. 4). It is seen from the diffraction on the left inset of Fig. 4b that the finest particles of Ti-Ni-based alloys are rather the oxides of the components of alloys components than the alloys themselves. It is interesting that the NiO particles are reduced to elemental Ni, and simultaneously, TiO is oxidized to TiO2 after the heating of the nanosized particles of Ni49Cu1Ti47Zr3 and Ni49.9Ti40.3Zr0.3Cu0.1Hf9.4 alloys. The phenomenon was observed independently on the ways of the heating described in details elsewhere [31, 32].

Direct composition measurements by EDX and EFTEM methods of the particle size 10 ÷ 100 nm confirm that their compositions differ from the master alloys for the most alloys under consideration. In the case of the multicomponent Zr57Cu20Al10Ni8Ti5 alloy, the composition differs from particle to particle (Fig. 6a). In Ni49Cu1Ti47Zr3 and Ni49.9Ti40.3Zr0.3Cu0.1Hf9.4 alloys, the fine particles are mostly the oxides of the alloy components [31, 32]. At the same time, the element stratification is observed in the particles of the Ni49.9Ti40.3Zr0.3Cu0.1Hf9.4 alloys with a diameter of ~20 ÷ 150 nm (Fig. 5). The core of such particles is an elemental Ni, the shell is TiO oxide, and the averaged compositions of such particles are close to Ni2Ti [32]. In addition, the diffraction patterns taken from the cores of such particles correspond to the FCC structure of the elemental Ni. Sometimes, particles, especially those with moderate sizes (20 ÷ 30 nm), have a strictly twinned structure (Fig. 5c). Twinning in nickel cores is likely to appear as a reaction on the stresses from the oxide layer, which covered the Ni core from all sides.

Among the powders under consideration, only the nanosized particles of Ni61.9Al38.1 alloy have the composition close to the composition of the master alloy (Fig. 6b), which could be explained by the particular relations between the vapor pressures of Ni and Al elements. Indeed, the average composition measured by EFTEM method in separate Ni-Al particle sizes of 10 ÷ 50 nm was Ni66.3-Al37.7 at.% while the average composition of agglomerates is Ni59.2Al40.8 at.%. The difference is likely caused by the layer of aluminum oxide, which covers the core of the particle with the composition close to Ni66.3Al37.7. This assumption is confirmed indirectly by the HRTEM method, which shows that most of such particles demonstrated striated contrast typical for the twinned structure of martensite crystals. In addition, the observed interplanar distances as well as their relations and the observed angles on the fast Fourier transforms (FFT) power spectra were practically the same as for L10 tetragonal structure of martensite, which is observed in bulk Ni-Al alloys with that composition. This situation drastically contrasts with the Ti-Ni-Hf cases, where striation contrast is caused by the twinning in the Ni core.

The discovery of the crystal structure of the particles of Ni46.7Ti49.2Zr3.41Cu0.8 alloy sized above ~100 ÷ 200 nm faced out the experimental difficulties. Those particles easily escaped from the field of view and/or carbon substrate due to any manipulation (tilting, rotation, focusing, etc.) needed to obtain good diffraction conditions, most of them were not transparent in addition. Nevertheless, in some cases one can say that such particles have a distinct crystal structure different from that of the smallest particles. Moreover, they are in a martensitic state.

In spite of the impossibility in obtaining perfect diffraction patterns, one can suppose that those of the group of reflexes, which form a certain part of a diffraction pattern, belong to the martensite (B19′ structure). Although identified correctly, zone axis was not possible (Fig. 8a) due to mentioned experimental reasons, and the observed interplanar distances were at least absolutely closed to martensitic distances in majority. Such particles usually had an internal structure revealed from selected area electron diffraction (SAED), which is very typical for martensite (Fig. 8a). The martensitic crystal structure of the relatively large particles indirectly confirms that such particles have the compositions close to the master alloy. Indeed, the martensite transformation in Ti-Ni-based alloys is possible only in a relatively narrow interval of Ni concentration near the quasi-equiatomic composition, with Zr and Hf replacing Ti and Cu replacing Ni [34].

A very interesting example of a particle with a size of 1 μm is shown on Fig. 8b. It seems to be a unique example when a diffraction pattern of acceptable quality could be indicated. Moreover, a so large particle (as for TEM studies) was transparent that clearly reveals the hollowness of the particle. The width of the walls observed as nontransparent circular border can be estimated as 50 nm.

Mechanisms of the Nanoparticles Formation

At least two main mechanisms of the formation of nanosized particles of spark erosion powder are possible. The difference between the compositions of nanosized fraction of powders and master alloys is the distinct feature, which supposes the formation of nanosized particles through the condensation of vapor elements of alloys. Definitely, the finest nanosized particles (less then ~10 nm) appear as a result of the condensation of the vapor elements of the alloys. Its compositions depend on the vapor pressures of its constituents, the regimes of the spark erosion processing, and contaminants in the coolant liquid. Because of the contamination of the coolant by oxygen and followed by passivation of powder, those particles are the oxides of the components of the alloys gathered in the agglomerates rather than the metallic particles actually.

In turn, the presence of relatively large particles (up to ~200 nm) also with different compositions than that of the alloy, which appear as stand-alone particles or as embedded in agglomerate, allows us to assume that scenarios of condensation could be different for the finest particles and particles that are moderate in sizes. It is not a great overstatement to suppose that moderate-sized particles are formed during much more time—long enough that different constituents are condensed in one particle. Certainly, the compositions of such particles are defined by the concentrations of elements in vapor, i.e., the vapor pressures. Occasionally, these concentrations in Ni-Al are such that provide the composition of nanosized particles close to the master alloy while in Ti-Ni-based alloys, the concentration of Ni is more than that of Ti; Hf was absent as a whole in Ti-Ni-Hf-nanosized powder [32]. This observation corresponds to the conclusions made in [28] that Ni is evaporated from the surface of molten droplets more extensively than Ti, Zr, and especially Hf providing concentration deviation in the micron-sized particles.

The extensive evaporation of elements during spark erosion processing goes at once with two main processes. First, evaporation accompanies an electrical discharge from the molten pool on the surface of the pieces of the material followed by the condensation on the walls of a gaseous bubble near the arc plasma column (Fig. 9a). Second, an occasion happens during the cooling of the molten droplets moving through the coolant (Fig. 9b). While the duration of the first process is around 10–100 μs (till the bubble collapses), the duration of the evaporation period under cooling is much shorter. In that case, condensation goes on the walls of small bubbles, which are continuously coming off from the moving molten droplets and then collapsing. It seems this process is responsible for the smallest nanoparticles formation.

On the mechanism of particles formation during spark erosion. a The potential difference between positively and negatively charged granules of a material induces the arc discharge through the small gap between them. Arc plasma channel 1 produces a lot of heat which melts and evaporates the material. Around the channel, the gaseous bubble 3 appears, by surface of which those evaporated constituents are condensed. The jets of melt are ejected from the pulls of molten material 2 on the surface of cathode and anode. Liquid jets are subsequently transformed in micron-sized droplets, which are quenched in situ into the coolant liquid 4. b Illustration of quenching in situ the molten droplet, which is moving through the cryogenic liquid (argon) surrounded by the bubble of gaseous argon and vapors of alloy components (Ti, Ni, and Hf in that case)

There is one more reason for the prolongation the vapor condensation in case of Ti-Ni-base alloys. The heat, which is realized during the formation of TiNi intermetallic compound, can slow down the cooling rate. Firstly, it provides further condensation of constituents, and secondly, the remelting of the agglomerates is composed of the earlier condensed particles even if such particles have already oxidized. In turn, strong affinity of Ti to oxygen provides the operation a kind of “oxygen pump”, which pulls out the oxygen atoms from the middles of such agglomerates to the surfaces simultaneously reducing the NiO oxide and producing TiO2 oxide. As a result, the Ni atoms tend to diffuse inside while Ti atoms to the surface of the particles. Thus, expansion of particles in size and the stratification of elements happen (Fig. 5).

At the same time, the particles, which have sizes above tens of nanometers, are solidified from the molten droplets thus reproducing the composition of the melt more or less for the most of the mentioned powders. One could expect that the amount of the submicron particles should be minor as it is in the case of the gas atomization. Indeed, the physical mechanism of the particles formation is very similar. It is the solidification of molten droplets formed due to the breaking of liquid jets, which are ejected from the molten pools of materials in case of spark erosion and sprayed from the nozzle in case of gas atomization. In both cases, the limitation factor is the surface tension, which restricts the particles size distribution from below. In both cases, the key role in the breaking mechanism plays the Rayleigh instability.

Another possible reason, which is responsible for the formation of the smallest particles in the case of spark erosion, can be explosive boiling of overheated molten jets followed by their explosion with formation submicron particles. This phenomenon can happen due to a rapid drop of pressure from 106 ÷ 1010 Pa to atmospheric pressure [10, 35, 36] when the discharge is broken and the gaseous bubble around the arc column collapses. One of the results of such scenario is blowing-out the hollow particles from the molten droplets oversaturated by a coolant gas [to be published]. Such a micron-sized hollow particle is shown on Fig. 8, but much more number of the micron-sized hollow particles has been observed in [13–15, 30]. A drastic difference between the cryogen gas solubility in molten droplets and in the solid phase, which is assumed in [14, 15], promotes the explosive boiling mechanism. Evidently, in the case of an explosive breaking of the molten hollow particle, the sizes of the ejected particles will be comparable with the bubble wall width, namely several submicrons.

Conclusions

Different morphology and composition of nanosized particles obtained in cryogenic liquids during the spark erosion processing of the pre-alloyed material supposes several mechanisms of their formation. One of them relates to the condensation of the evaporated constituents of alloy under consideration, and the finest particles (less then ~10 nm) are the oxides of the components of the alloy rather than alloy itself. In any case, the particles of all sizes are covered with the oxide layer. The observed composition of the condensed nanoparticles sized above than ~10 nm depends on (a) the relations between the vapor pressures of the constituents of the alloy, (b) duration of the condensation process, (c) alloy composition and affinity of the constituents to oxygen, and (d) the conditions of storage and manipulation with the powder. Therefore, the composition of such particles can be very close to the master alloy (Ni66.3Al37.7), which strongly differs from particles to particles for the multicomponent alloys (Zr57Cu20Al10Ni8Ti5) and in addition, can be stratified (Ti-Ni-based alloys). Another mechanism, which is responsible for the formation of particle sizes above several tens and even hundreds nanometers, ensures the coincidence of the composition of the nanoparticles with the master alloys. It supposes that the explosive breaking of the molten micron-sized bubbles or droplets ejected from the melt pools on the surface of the granules of the material.

Abbreviations

- BF:

-

bright field (image)

- DF:

-

dark field (image)

- EDX:

-

energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy

- EFTEM:

-

energy-filtered transmission electron microscopy

- FFT:

-

fast Fourier transforms

- HRTEM:

-

high-resolution transmission electron microscopy

- SAED:

-

selected area electron diffraction

- SEM:

-

scanning electron microscopy

- TEM:

-

transmission electron microscopy

- XRD:

-

X-ray diffraction

References

Tomochika H, Kikuchi H, Araki T, Nishida M (2003) Fabrication of NiTi intermetallic compound by a reactive gas laser atomization process. Mater Sci Eng A 356:122–129

Ibarra A, Rodriguez PP, Recarte V, Pérez-Landazábal JI, Nó ML, San JJ (2004) Internal friction behaviour during martensitic transformation in shape memory alloys processed by powder metallurgy. Mater Sci A 370:492–496

Porter GA, Liaw PK, Tiegs TN, Wu KH (2000) Particle size reduction of NiTi shape-memory alloy powders. Scr Mater 43:1111–1117

Maziarz W, Dutkiewicz J, Van Humbeeck J, Czeppe T (2004) Mechanically alloyed and hot pressed Ni–49.7Ti alloy showing martensitic transformation. Mater Sci A 375–377:844–848

Li-Huia Z, Qing-Wei H (2003) Study on martensitic transformation of mechanically alloyed nanocrystalline Fe–Ni. Mater Lett 57:4070–4073

Liu Y, Zhang J, Yu L, Jia G, Jing C, Cao S (2005) Magnetic and frequency properties for nanocrystalline Fe–Ni alloys prepared by high-energy milling method. J Magn Magn Mater 285(1-2):138–144

Fu Y, Shearwood C (2004) Characterization of nanocrystalline TiNi powder. Scr Mater 50:319–323

Tepper F (2000) Nanosize powders produced by electro-explosion of wire and their potential applications. Powder Metall 43(4):320–322

Frommen C, Wilde G, Rösner H (2004) Wet-chemical synthesis and martensitic phase transformation of Au–Cd nanoparticles with near-equiatomic composition. J Alloys and Compounds 377:232–242

Berkowitz AE, Walter JL (1987) Spark erosion: a method for producing rapidly quenched fine powders. J Mater Res 2:277–288

Berkowitz AE, Hansen MF, Parker FT, Vecchio KS, Spada FE, Lavernia EJ, Rodriguez R (2003) Amorphous soft magnetic particles produced by spark erosion. J Magn Magn Mater 254–255:1–6

Berkowitz AE, Walter JL (1982) Amorphous particles produced by spark erosion. Mat Sci Eng 55:275–287

Nersessian N, Or SW, Carman GP, Choe W, Radousky HB (2004) Hollow and solid spherical magnetostrictive particulate composites. J Appl Phys 96:3362–3365

Berkowitz AE, Harper H, Smith DJ, Hu H, Jiang Q, Solomon VC, Radousky HB (2004) Hollow metallic microspheres produced by spark erosion. Appl Phys Let 85:940–942

Solomon VC, Hong J, Tang YJ, Berkowitz AE, Smith DJ (2007) Electron microscopy investigation of spark-eroded Ni–Mn–Ga ferromagnetic shape-memory alloy particles. Scr Mat 56:593–596

Wan H, Berkowitz AE (1995) Structure and magnetic properties of Nd-FeB fine particles produced by spark erosion. Scr Metall Mat 32:1827–1831

Nguyen PK, Jin S, Berkowitz AE (2014) MnBi particles with high energy density made by spark erosion. J Appl Phys 115:17A7561–17A7563

Tang YJ, Parker FT, Harper H, Berkowitz AE, Jiang Q, Smith DJ, Brand M, Wang F (2004) Co50Fe50 fine particles for power frequency applications. IEEE Trans on Mag 40:2002–2004

Kolbasov GY, Ustinov AI, Shcherba AA, Perekos AY, Danilov MO, Vyunova NV, Zakharchenko SN, Hossbah G (2005) Application of volumetric electric-spark dispersion for the fabrication of Ti–Zr–Ni hydrogen storage alloys. J Power Sources 150:276–281.

Cabanillas ED, López M, Pasqualini EE, Lombardo DJC (2004) Production of uranium–molybdenum particles by spark-erosion. J Nuclear Materials 324:1–5

Calugaru G, Hopulele I (1999) Structure and magnetic properties of Al–Ni–Co fine particles produced by spark erosion. Powder Metallurgy 42:367–368

Tang YJ, Smith DJ, Hu H, Spada FE, Harper H, Berkowitz AE (2003) Structure and phase transformation of ferromagnetic shape memory alloy Ni49Mn30Ga21 fine particles prepared by spark erosion. IEEE Trans on Mag 39:3405–3407

Solomon VC, Smith DJ, Tang YJ, Berkowitz AE (2004) Microstructural characterization of Ni-Mn-Ga ferromagnetic shape memory alloy powders. J Appl Phys 95:6954–6956

Nguyen PK, Lee KH, Moon J, Kim SI, Ahn KA, Chen LH, Lee SM, Chen RK, Jin S, Berkowitz AE (2012) Spark erosion: a high production rate method for producing Bi0.5Sb1.5Te3 nanoparticles with enhanced thermoelectric performance. Nanotechnology 23:415604–415611

Carrey J, Radousky HB, Berkowitz AE (2004) Spark-eroded particles: influence of processing parameters. J Appl Phys 95:823–829

Shcherba AA, Podoltsev AD, Kucheryavaya IN (2004) Spark erosion of conducting granules in a liquid: analysis of electromagnetic, thermal and hydrodynamic processes. Tekhn Elektrodin 6:4–18

Monastyrsky GE, Ochin P, Wang GY, Kolomytsev VI, Koval Y, Tinkov VO, Shcherba AA, Zaharchenko SM (2011) Structure and composition of titanium spark erosion powder obtained in liquid nitrogen. Chem Met Alloys 4(1/2):126–142, http://www.chemetal-journal.org. Accessed 5 December 2015

Monastyrsky GE, Ochin P, Wang GY, Gilchuk AV, Kolomytsev VI, Koval YN, Tinkov VO, Shcherba AA, Zaharchenko SM (2011) Effect of particle size on the chemical composition of Ti–Ni-base spark erosion powder obtained in liquid argon. Chem Met Alloys 4(3/4):188–199, http://www.chemetal-journal.org. Accessed 5 December 2015

Monastyrsky GE, Yakovenko PA, Kolomytsev VI, Koval YN, Shcherba AA, Portier R (2008) Characterization of spark-eroded shape memory alloy powders obtained in cryogenic liquids Mat. Sci Eng A 481–482:643–646

Ochin P, Gilchuk AV, Monastyrsky GE, Kolomytsev VI, Koval YN, Shcherba AA, Zaharchenko SM (2013) Martensitic transformation in spark plasma sintered compacts of Ni-Mn-Ga powders prepared by spark erosion method in cryogenic liquids. Mat Sci Forum 738–739:451–455

Ivanova OM, Danylenko MI, Monastyrsky GE, Kolomytsev VI, Koval YM, Shcherba AA, Zaharchenko SM, Portier R (2009) Doslidzhennya mehanizmiv utvorennya nanoporoshkiv Ti-Ni-Zr-Cu, otrimanih metodom elektroiskrovoyi eroziyi v kriogennih ridinah (in ukrainan). Metallofizika i Noveishie Tekhnologii 31:603–614

Monastyrsky GE, Kolomytsev VI, Koval YM, Wang G, Ochin P, Ivanova OM, Danylenko MI (2011) Strukturnye issledovaniya poroshkov iz splavov s effektom pamyati formy na osnove Ti–Ni–Hf, poluchennyh metodom elektroiskrovoy erozii v zhidkom argone (in ukrainan). Metallofizika i Noveishie Tekhnologii 33:289–300

Bang CK, Hong YC, Uhm HS (2007) Synthesis and characterization of nano-sized nitride particles by using an atmospheric microwave plasma technique. Surf Coat Technol 201:5007–5011

Kolomytsev VI, Babanly M, Pasko A, Shpak AP, Sych T, Ochin P, Vermaut P, Portier R, Cesari E, Rafaja D (2008) Shape memory behavior in some (Ti, Zr, Hf)50(Ni, Cu)50 alloys elaborated by glass devitrification. Advances in Science and Technology 59:113–118

Crichton IM, McGeough JA, Munro W, White C (1981) Comparative studies of ecm, edm and ecam. Precis Eng 3:155–160

Tao J, Ni J, Shih AJ (2012) Modeling of the anode crater formation in electrical discharge machining. J Manufact Sci Eng 134:0110021–0110032

Acknowledgements

Author gratefully thanks his colleagues Profs. Yu.N. Koval, A.A. Shcherba, V.I. Kolomytsev, P. Ochin, R. Portier and Drs. A.V. Kotko, A.V. Gilchuk, M.I. Danylenko, G.Y. Wang, S.M. Zakharchenko for the assistance and permanent fruitful discussions about the subject of current work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing Interests

The author declares that he has no competing interests.

Author’s Contributions

GM conceived the idea of using transmission electron microscopy and high-resolution electron microscopy techniques for characterization of the finest nanoparticles to clarify the spark erosion powder formation mechanism. GM also participated in the design and preparation of the alloys and powders as well as the acquisition of the data, analysis, and their interpretation; wrote the manuscript; and coordinated the study of spark erosion powders at whole.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Monastyrsky, G. Nanoparticles formation mechanisms through the spark erosion of alloys in cryogenic liquids. Nanoscale Res Lett 10, 503 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1186/s11671-015-1212-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s11671-015-1212-9

Keywords

- Nanoparticles of alloys

- Nanopowders

- Spark erosion method

- Shape memory alloys

- Glass-forming Zr-based alloys

- Martensite

- TEM

- HRTEM