Abstract

Background

Argonaute 2 (AGO2), the only protein with catalytic activity in the human Argonaute family, is considered as a key component of RNA interference (RNAi) pathway. Here we performed a yeast two-hybrid screen using the human Argonaute 2 PIWI domain as bait to screen for new AGO2-interacting proteins and explored the specific mechanism through a series of molecular biology and biochemistry experiments.

Methods

The yeast two-hybrid system was used to screen for AGO2-interacting proteins. Co-immunoprecipitation and immunofluorescence assays were used to further determine interactions and co-localization. Truncated plasmids were constructed to clarify the interaction domain. EGFP fluorescence assay was performed to determine the effect of PSMC3 on RNAi. Regulation of AGO2 protein expression and ubiquitination by PSMC3 and USP14 was examined by western blotting. RT-qPCR assays were applied to assess the level of AGO2 mRNA. Rescue assays were also performed.

Results

We identified PSMC3 (proteasome 26S subunit, ATPase, 3) as a novel AGO2 binding partner. Biochemical and bioinformatic analysis demonstrates that this interaction is performed in an RNA-independent manner and the N-terminal coiled-coil motif of PSMC3 is required. Depletion of PSMC3 impairs the activity of the targeted cleavage mediated by small RNAs. Further studies showed that depletion of PSMC3 decreased AGO2 protein amount, whereas PSMC3 overexpression increased the expression of AGO2 at a post-translational level. Cycloheximide treatment indicated that PSMC3 depletion resulted in a decrease in cytoplasmic AGO2 amount due to an increase in AGO2 protein turnover. The absence of PSMC3 promoted ubiquitination of AGO2, resulting in its degradation by the 26S proteasome. Mechanistically, PSMC3 assists in the interaction of AGO2 with the deubiquitylase USP14(ubiquitin specific peptidase 14) and facilitates USP14-mediated deubiquitination of AGO2. As a result, AGO2 is stabilized, which then promotes RNAi.

Conclusion

Our findings demonstrate that PSMC3 plays an essential role in regulating the stability of AGO2 and thus in maintaining effective RNAi.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

The Argonaute proteins were first identified in plants [1] and are highly conserved across species, with many organisms encoding multiple family members [2]. Argonaute proteins can be subdivided phylogenetically into the AGO subfamily and the PIWI subfamily. Human AGO subfamily consists of four Argonaute genes (AGO1, AGO2, AGO3, and AGO4), which are ubiquitously expressed and associated with miRNAs and siRNAs[3, 4]. Although they all suppress translation of their target mRNAs, only AGO2 has the slicer activity, and a catalytic triad consisting of Asp-Asp-His motif has been identified in this protein [5, 6]. AGO2 consists of four functional core domains (N, PAZ, MID, and PIWI) and two domain linkers (L1 and L2) [7]. The analysis of the crystal structure of AGO2-bound pre-miRNAs showed the N domain initiates duplex RNA unwinding during RISC (RNA-induced silencing complex) assembly, the PAZ domain is an RNA binding module that specifically recognizes the 3′-protruding ends of the small RNAs, the MID domain harbors the 5′-phosphate of the guide RNAs, and the PIWI domain contains an RNaseH-like structure, which is necessary for mRNA cleavage [8,9,10]. Current studies on AGO2 have shown that it can be involved not only in cytoplasmic RNAi, but also in gene regulatory processes in nuclei [11,12,13]. Moreover, AGO2 has also been found to regulate other cellular processes, such as alternative polyadenylation, transposon repression, and translational activation [14,15,16]. In addition, direct regulation of the stemness genes by nuclear AGO2 is also crucial for stem cell self-renewal, survival, and differentiation [17].

RNA interference depends on RNA-induced silencing complex to regulate gene expression. During RNAi, small RNAs are loaded into the complex and then the complex recognizes the target mRNA [18, 19]. Perfect complementarity between the small RNAs and the target mRNAs promotes endonucleolytic cleavage [20], whereas mismatches lead to suppression of gene expression through translational repression or mRNA deadenylation [21]. Given that AGO2 is a core component and catalytic engine of RISC, it is essential for small-RNA-guided posttranscriptional gene silencing. Many proteins have been identified to be associated with AGO2 and function in both RNAi and miRNA pathways[22,23,24]. The PIWI domain of human Argonaute proteins has been shown to contain an RNaseH-like structure, which is not only necessary for AGO2-mediated targeted mRNAs cleavage guided by small RNAs [7, 9], but is also involved in protein–protein interaction between Argonaute and Dicer [25], TRBP [26], and GW182 [27]. Here we identified PSMC3 as a novel AGO2-interacting protein in a yeast two-hybrid screen using the PIWI domain of AGO2 as bait. PSMC3 is a multifunctional protein directly involved in the regulation of gene transcription as well as in protein degradation [28, 29]. We support a critical role of PSMC3 in ubiquitin-mediated proteasomal degradation of AGO2, which further also impacts the targeted cleavage mediated by small RNAs.

Methods

Plasmids and oligos

The generation of constructs used in this study is detailed in Additional file 1: Experimental Procedures.

Antibodies and reagents

Anti-HA, anti-Myc, anti-Flag, anti-GFP, and anti-ubiquitin primary antibodies were from Sigma-Aldrich (MO, USA). Immunoaffinity-purified rabbit polyclonal antibodies against AGO2, PSMC3, and GAPDH were from Saier Biotech (Tianjin, China). Horseradish-peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse and anti-rabbit secondary antibodies were from Zhongshan Goldenbridge Biotechnology (Beijing, China). FITC/TRITC-conjugated secondary antibodies were purchased from Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratories (PA, USA).

MG132 was obtained from Calbiochem (Darmstadt, Germany), and chloroquine (CQ) and cycloheximide (CHX) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (MO, USA). Compounds were dissolved in DMSO and used at the concentrations indicated.

Yeast two-hybrid screen

A Stratagene Cytotrap system human lung library (La Jolla, CA, USA) was screened according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Further details are provided in Additional file 1: Experimental Procedures.

Cell culture and transfection

HeLa cells, Huh7 cells, and A549 cells were obtained from ATCC cell bank and kept by the laboratory. HeLa cells were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium containing 10% FBS in a 37 °C incubator with 5% CO2. Huh7 cells and A549 cells were maintained in DMEM medium containing 10% FBS in a 37 °C incubator with 5% CO2. Cell transfection was performed using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen, CA, USA) following the manufacturer’s protocol; details are provided in Additional file 1: Experimental Procedures. To generate stable cell lines, HeLa cells were transfected with pcDNA3/EGFP, pcDNA3/EGFP-miR-21 (1× perfect), or pcDNA3/EGFP-CXCR4 (4× bulged) reporter constructs, and neomycin-resistant clones were tested for their ability to yield an EGFP-positive phenotype. For the reporter plasmid carrying EGFP under the regulation of miR-21, the repression of EGFP could be reversed when endogenous miR-21 was blocked by an anti-miR-21 oligonucleotide.

Co-immunoprecipitation and immunofluorescence

Details are provided in Additional file 1: Experimental Procedures.

Western blotting

Total protein from HeLa cells transfected with either siRNA or plasmids was extracted using RIPA buffer (1 mM MgCl2, 10 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.4, 0.1% SDS, 1% NP-40), and protein expression was analyzed by western blotting. GAPDH served as a loading control. Bands were quantified with Labworks 4.0 software.

Preparation of cytoplasmic and nuclear fractions

The subfractionation of transfected cells into nuclear and cytoplasmic extracts was performed as previously described [30]. Details are provided in Additional file 1: Experimental Procedures.

Isolation of total RNA and qRT-PCR

Total RNA was extracted from transfected HeLa cells using Tri-Reagent (Sigma-Aldrich, MO, USA). RNAs were reverse transcribed into cDNA using M-MLV Reverse Transcriptase (TaKaRa, Madison, WI) as specified by the manufacturer. Details are provided in Additional file 1: Experimental Procedures.

In vivo ubiquitination assay

Details are provided in Additional file 1: Experimental Procedures.

EGFP fluorescence assay

Details are provided in Additional file 1: Experimental Procedures.

Statistics

Statistical significance was determined using a two-tailed homoscedastic Student’s t-test. For all data analyzed, values were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD), and P < 0.05 was considered to be significant. The data generated were representative of at least three separate experiments.

Results

Identification of AGO2 interaction proteins

To identify novel proteins associated with human AGO2, we employed the CytoTrap two-hybrid system to screen a human lung cDNA library using the AGO2 PIWI domain as bait (Fig. 1a). This system performed better than conventional GAL4 and LexA two-hybrid systems in assaying interactions in the cytoplasm [31], the main site of AGO2 localization. We selected the positive interacting colonies on the basis of their ability to grow in appropriate selection medium at 37 °C, and their inserts were sequenced (Fig. 1b). After alignment, four interacting proteins were identified as proteasome 26S subunit, ATPase 3 (PSMC3), retinoblastoma binding protein 6 (RBBP6), DNA fragmentation factor subunit alpha (DFFA), and protein activator of the interferon induced protein kinase (PACT), which has been reported to physically interact with AGO2 [32].

Four proteins interacting with AGO2 were screened and two promote RNAi. a Schematic of yeast two-hybrid system used to identify the AGO2 interaction proteins. b The interactive clones isolated from a human lung cDNA library were reconfirmed by cotransfection into naive cdc25H yeast with pSOS AGO2-PIWI or the following negative control plasmids: pSOS vector (containing the human SOS gene only), pSOS-MAFB (fusion of the hSOS gene and the transcription factor MAFB) and pSOS-Col I (fusion of the hSOS gene and type IV collagenase). No interaction was detected when the interactive clones were cotransfected with the control plasmids. Accession number of each positive gene is shown

The coiled-coil region of the N-terminus of PSMC3 interacts with AGO2 in an RNA-independent manner

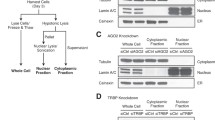

Current studies have shown that some proteins interact with AGO2 in an RNA-dependent manner, while some are RNA independent, which leads to different functions [27, 33,34,35]. To determine the specific interaction of AGO2 with PSMC3 and whether this interaction is dependent on RNA, we treated the lysates using RNase A and then performed co-IP with the ectopically expressed proteins in HeLa cells (Fig. 2a). Our result demonstrates that PSMC3 interacts with AGO2 in an RNA-independent manner. To further validate the specificity of this interaction, we also performed co-IP in A549 and Huh7 cells (Additional file 1: Fig. S1a, b), with the same results. Immunofluorescence detection was performed to validate the subcellular co-localization of PSMC3 and AGO2. As shown in Fig. 2b, PSMC3 was primarily localized with AGO2 in the cytoplasm, and there appeared to be minor co-localization in the nucleus. Some studies have shown the presence of PSMC3 and AGO2 in both cytoplasm and nucleus [29, 36,37,38,39,40]. To clarify whether this interaction exists in both compartments, we first validated their respective cellular localization with nucleoplasmic isolation (Fig. 2c) and immunofluorescence assays (Additional file 1: Fig. S1c), and the results were in accordance with the reports. Then we isolated nucleic or cytoplasmic extracts and performed co-IP assays that confirmed the interaction is present in both compartments (Fig. 2d). PSMC3 is known to possess an N-terminal coiled-coil domain and a highly conserved AAA (ATPases Associated with a wide variety of cellular Activities) superfamily ATPase domain, which contains a nucleotide-binding motif (ATP-binding site) and a helicase motif [28, 36, 41]. To identify the minimal region of PSMC3 necessary for the PSMC3–AGO2 interaction, full-length and specific-length PSMC3 cDNAs were tested against the AGO2 PIWI domain by yeast two-hybrid assay. The N-terminal portion of PSMC3 was found to be required for the interaction (Fig. 2e, f). Co-immunoprecipitation assays further confirmed this result (Fig. 2g). Coiled-coil domains are commonly involved in protein–protein interactions, and the coiled-coil portion of PSMC3 has been reported to be involved in interactions with p14ARF [36]. Here, our results indicate that the coiled-coil region of the N-terminus of PSMC3 is required for binding to AGO2.

The coiled-coil region of the N-terminus of PSMC3 interacts with human AGO2. a PSMC3 interacts with AGO2 in an RNA-independent manner. HeLa cells were co-transfected with HA-AGO2-PIWI and Flag-PSMC3. Immunoprecipitation assays were performed with anti-HA antibody and western blotting with anti-Flag and anti-HA antibodies. For lanes 4, 5, and 6, cell lysates were incubated at room temperature with RNase A (10 mg/ml) for 30 min. b PSMC3 colocalizes with AGO2 in HeLa cells. Myc-PSMC3 was transfected into HeLa cells. Forty-eight hours after transfection, immunofluorescence assays were performed with the indicated antibodies, then imaged by confocal microscopy. Scale bar, 10 µm. c Western blotting assays were used to detect AGO2 and PSMC3 protein levels in nucleoplasm or cytoplasm from HeLa cells. d PSMC3 interacts with AGO2 in both nucleoplasm and cytoplasm. HeLa cells were co-transfected with HA-AGO2 -PIWI and Flag-PSMC3. Then nucleoplasmic or cytoplasmic extracts were harvested and analyzed by western blotting assays. e Schematic representation of the full-length and truncated PSMC3s used to map AGO2-binding sites. PSMC3 possesses an N-terminal domain and an AAA ATPase domain that contains an ATP-binding motif (black box) and a helicase motif (white box). f A yeast two-hybrid system was used to determine whether pSOS-AGO2-PIWI could interact with the full-length PSMC3 protein or with deletion mutants PSMC3 (214–439), PSMC3 (354–439), PSMC3 (1–214), and PSMC3 (97–439). g Mapping the AGO2-interacting site in PSMC3. HeLa cells were transfected with the indicated plasmids encoding Flag-tagged full-length PSMC3 or PSMC3 deletion mutants. After 48 h, cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-AGO2 antibody and then western blotting was performed with anti-Flag and anti-AGO2 antibodies. All results are representative of three independent experiments

PSMC3 is required for efficient RNAi

To determine whether PSMC3 is involved in RNAi pathway, an EGFP fluorescence assay was performed to assess the effect of PSMC3 on siRNA-induced specific target RNA cleavage, in which the expression of exogenous EGFP was knocked down by specific siRNA (Additional file 1: Fig. S2a). As shown in Fig. 3a, depletion of AGO2 (Additional file 1: Fig. S3a, b) completely abolished RNAi activity, which is consistent with previous reports [6, 42]. The levels of EGFP protein were increased in PSMC3-depleted (Additional file 1: Fig. S3c) cells relative to control cells (Fig. 3a and Additional file 1: Fig. S2b, c), indicating that PSMC3 knockdown reduced siRNA-induced siRISC activity. However, the expression of siRNA-resistant PSMC3 mutant (Additional file 1: Fig. S3d) rescued this siRISC activity (Fig. 3b). To determine the functional role of PSMC3 in miRNA-mediated gene silencing, an EGFP-based positive readout reporter assay was applied as previously described [23, 43, 44]. When reporter plasmid pcDNA3/EGFP-miR-21 (1× perfect), which encodes EGFP mRNA containing a fully complementary miR-21 sequence, was transfected into HeLa cells, we observed low EGFP levels due to the effects of endogenous miR-21. However, this repression of EGFP could be reversed by transfection with anti-miR-21 oligonucleotides (Additional file 1: Fig. S2d). Consistent with the knockdown of AGO2, depletion of PSMC3 also relieved endogenous miR-21-mediated repression of the EGFP reporter (Fig. 3c; Additional file 1: Fig. S2d–e). Expression of the siRNA-resistant PSMC3 mutant overrode the effect of PSMC3 knockdown on miRNA-induced siRISC cleavage activity (Fig. 3d). These results demonstrate that PSMC3 is specifically required for small RNA-induced mRNA cleavage in HeLa cells.

PSMC3 is required for efficient RNAi. a Depletion of PSMC3 abolishes the siRNA-mediated cleavage of EGFP mRNA. Overview of the siRNA-mediated cleavage of target mRNA (left). A stable HeLa cell line expressing EGFP was either untransfected or transfected with the indicated siRNAs. pDsRed2-N1, a plasmid expressing RFP (red fluorescent protein), was also included for normalization. After 48 h, expression ratios between the EGFP and RFP reporters were calculated on an F-4500 fluorescence spectrophotometer (right). b Expression of the siRNA-resistant PSMC3 mutant overrides the effect of PSMC3 depletion on RNAi. EGFP-expressed HeLa cells were transfected with siNC or siPSMC3, together with pcDNA3 plasmid only or vectors expressing wild-type (wt) or siRNA-resistant (mut) PSMC3. After 24 h, cells were re-transfected with EGFP siRNA. The fluorescence value in the siNC treatment was set to 1. c PSMC3 is required for miR-21-mediated mRNA cleavage. Schematic of the miRNA-mediated cleavage of target mRNA (left). A stable HeLa cell line expressing EGFP-miR-21 (which contains a sequence with 1× perfect complementarity to miR-21 in its 3′ UTR) was transfected with the indicated siRNAs. The ratio of EGFP to RFP was normalized to quantify the effect of depleting AGO2 and PSMC3 on RNAi (right). d Expression of siRNA-resistant PSMC3 mutant rescues the cleavage activity of miRISC. EGFP-miR-21-expressing HeLa cells were transfected with control or PSMC3 siRNAs together with pcDNA3 plasmid only or vectors expressing wild-type (wt) or siRNA-resistant mutant (mut) PSMC3. The fluorescence value was detected on an F-4500 fluorescence spectrophotometer. e Depletion of PSMC3 has no effect on translational repression. Diagram of the siRNA-mediated translational repression of target mRNA (left). A stable HeLa cell line expressing EGFP-CXCR4 (which contains a sequence with 4× bulged CXCR4 binding sites in its 3′ UTR) was transfected with siRNAs targeting AGO2 or PSMC3. After 24 h, cells were re-transfected with control siRNA or CXCR4 siRNA. EGFP protein levels were measured and normalized to RFP as a control (right). In all statistical comparisons, three independent experiments were performed (mean ± SD, n = 3, Student’s t-test). *, P < 0.05, **, P < 0.01, ***, P < 0.001, ****, P < 0.0001

We next used a chemokine (C-X-C motif) receptor 4 (CXCR4) reporter system [45,46,47] to determine whether the absence of PSMC3 impacts cleavage-independent repression. Four bulged CXCR4 siRNA target sites were introduced into the 3′ UTR of the EGFP reporter gene. HeLa cells stably expressing pcDNA3/EGFP-CXCR4 (4× bulged) were transfected with the indicated siRNAs. As shown in Fig. 3e and Additional file 1: Fig. S2f, g, silencing of AGO2 led to a significant derepression of the siRNA reporters, whereas PSMC3 depletion had no effect. Taken together, our results demonstrate that PSMC3 depletion results in the inhibition of small-RNA-mediated mRNAs cleavage but not cleavage-independent translation suppression.

PSMC3 regulates the stability of cytoplasmic AGO2 protein at a posttranslational level

It has been investigated that PSMC3 can regulate the amounts of some specific proteins at the posttranslational level [29, 36]; we therefore hypothesized that PSMC3 may regulate the expression of AGO2. So, we examined the effect of PSMC3 on the levels of AGO2 in HeLa cells by western blotting. The results showed that AGO2 protein levels decreased in PSMC3-depleted cells and increased in PSMC3-overexpressed cells relative to the control (Fig. 4a). To further confirm that PSMC3 could directly modulate the abundance of AGO2, wild-type PSMC3 and the PSMC3 mutant were co-transfected into HeLa cells with the indicated siRNAs. The expression of the siRNA-resistant PSMC3 mutant overrode the suppression of AGO2 caused by knockdown of the wild-type PSMC3 (Fig. 4b).

PSMC3 is essential to maintain AGO2 protein levels. a PSMC3 increases AGO2 protein levels. HeLa cells were transfected with the indicated plasmids. Extracts were collected at 48 h post-transfection and subjected to western blotting analysis with anti-AGO2 and anti-GAPDH antibodies. b Expression of siRNA-resistant PSMC3 abrogates the suppression of AGO2 caused by PSMC3-specific depletion. HeLa cells were co-transfected with plasmids encoding either the wild-type (wt) or mutant (mut) PSMC3 along with siPSMC3 or control siRNA. After 48 h, lysates were analyzed by western blotting with anti-AGO2 and anti-GAPDH antibodies. c Real-time RT-PCR analysis of endogenous AGO2 mRNA was performed using total RNA isolated from HeLa cells after 48 h of transfection with the indicated plasmids. GAPDH mRNAs served as the control. In all statistical comparisons, three independent experiments were performed (mean ± SD, n = 3, Student’s t-test). d Depletion of PSMC3 increases AGO2 protein turnover. HeLa cells were transfected with control or PSMC3 siRNA. After 48 h, the cells were treated with 100 µg/mL of cycloheximide (CHX) for the indicated periods and then harvested for immunoblotting with anti-AGO2 and anti-GAPDH antibodies (left). The results were plotted after quantitation (right). e Depletion of PSMC3 decreases the amount of AGO2 in the cytoplasm. HeLa cells were co-transfected with the indicated plasmids. Then nucleoplasmic or cytoplasmic extracts were harvested and analyzed by western blotting assays with anti-Flag, anti-GAPDH (cytoplasmic marker), and anti-LMNB1 (nucleoplasmic marker) antibodies. All results are representative of three independent experiments

To further determine at which level PSMC3 affects the AGO2 protein concentration, we tested whether this was due to the changes in transcription or the stability of the AGO2 mRNA. RT-qPCR showed that PSMC3 does not influence the AGO2 mRNA levels (Fig. 4c). This result suggests that PSMC3 modulates the amount of AGO2 at post-translational level. We then performed a cycloheximide assay to determine whether the decline in AGO2 levels in PSMC3-depleted cells was caused by an increase of AGO2 protein turnover. As shown in Fig. 4d, knockdown of PSMC3 shortened the half-life of the AGO2 protein in HeLa cells, and AGO2 decayed at higher rates during the time course relative to the control.

Given the interaction of AGO2 with PSMC3 in both the cytoplasm and the nucleus (Fig. 2d), we next performed a nucleoplasmic isolation assay. The results demonstrated that cytoplasmic AGO2 was changed to a greater extent than nuclear AGO2, indicating that PSMC3 primarily regulates the stability of AGO2 protein in the cytoplasm (Fig. 4e). Immunofluorescence analysis also showed the same result (Additional file 1: Fig. S4a). Meanwhile, we also examined the effect of AGO2 on PSMC3 protein levels and found that it did not affect PSMC3 protein levels (Additional file 1: Fig. S4b). These results suggest that PSMC3 regulates the stability of cytoplasmic AGO2 protein at posttranslational level.

Depletion of PSMC3 results in reduced USP14 deubiquitination of AGO2

It has been reported that the AGO2 protein can be posttranslationally modified: modifications such as hydroxylation, phosphorylation, and ubiquitination influence AGO2 stability [48,49,50,51,52]. Rybak et al. demonstrated that AGO2 is ubiquitinated by the E3 ubiquitin ligase mLin41 (mouse homolog of lin41) [50]. So, we examined the degradation pathway of AGO2 protein by using the lysosomal inhibitor chloroquine or the proteasome inhibitor MG132. Upon treatment with MG132 but not chloroquine, high-molecular-weight forms of AGO2 accumulated (Fig. 5a), indicating that AGO2 was ubiquitinated in vivo. To further identify the ubiquitination sites of AGO2, two ubiquitin site prediction algorithms, BDM-PUB (http://bdmpub.biocuckoo.org/prediction.php) and UbPred (http://www.ubpred.org/) were used, which predicted that the C-terminal region of AGO2 contains five lysine residues that are potential targets for ubiquitination (Additional file 1: Fig. S5a). To investigate the role of these residues in the ubiquitin-dependent degradation of AGO2, single and multiple mutations of lysine to arginine (K-to-R) were introduced into the amino acid sequence of AGO2 (Additional file 1: Fig. S5b). MG132 treatment resulted in the increased ubiquitination of ectopically expressed HA-tagged AGO2 relative to DMSO treatment. While single (K726R) or double (K607/608R, K820/844R) lysine residue mutations had little effect on AGO2 ubiquitination, a decline in ubiquitin-linked AGO2 was observed with the 4KR mutant, which contained K-to-R changes at positions 607, 608, 820, and 844. Mutations of all five lysine residues (5KR) showed no significant difference when compared with 4KR (Additional file 1: Fig. S5c), indicating that lysine residue 726 is not a ubiquitination site in AGO2.

Depletion of PSMC3 inhibits USP14 upregulation of AGO2 proteins. a AGO2 degradation via proteasome pathway. After Hela cells were treated with the indicated doses of chloroquine for 18 h, AGO2 protein levels were measured by western blotting assays (left). HeLa cells were incubated with the proteasome inhibitor MG132 (30 µM) or with DMSO for 10 h. Whole-cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-AGO2 antibody and analyzed with anti-ubiquitin, anti-GAPDH, and anti-AGO2 antibodies (right). b,c Depletion of PSMC3 facilitates AGO2 ubiquitination. b HeLa cells were transfected with the indicated plasmids. After 36 h, cells were treated with or without 30 µM MG132 for 10 h. AGO2 protein levels were analyzed by western blotting assays. c HeLa cells were transfected with control or PSMC3 siRNAs. After 36 h, cells were incubated with MG132 (30 µM) for 10 h. Whole-cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-AGO2 antibody and analyzed with anti-ubiquitin, anti-GAPDH, and anti-AGO2 antibodies. d The PPI network analysis of PSMC3 by the STRING database. e The top 20 biological process (BP) terms in the enrichment analysis of the PSMC3-interacting proteins. f,g PSMC3 (f) and AGO2 (g) both interact with USP14. HeLa cells were co-transfected with the indicated plasmids. Immunoprecipitation assays were performed with anti-HA antibody and western blotting with anti-Flag antibody. h,i AGO2 is deubiquitinated by USP14. h HeLa cells were transfected with the indicated plasmids. After 36 h, cells were treated with (bottom) or without (top) 30 µM MG132 for 10 h. AGO2 protein levels were analyzed by western blotting assays. i HeLa cells were transfected with the indicated plasmids. After 36 h, cells were incubated with MG132 (30 µM) for 10 h. Whole-cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-AGO2 antibody and analyzed with anti-ubiquitin, anti-GAPDH, and anti-AGO2 antibodies. j HeLa cells were treated with or without IU1 (an inhibitor of the enzymatic activity of USP14) and MG132 (30 µM) for 10 h. Whole-cell lysates were immunoprecipitated with anti-AGO2 antibody and analyzed with anti-ubiquitin, anti-GAPDH, and anti-AGO2 antibodies. k Depletion of PSMC3 inhibits USP14 upregulation of AGO2 proteins. HeLa cells were transfected with the indicated plasmids and then AGO2 protein levels were analyzed by western blotting assays after 48 h. l HeLa cells were transfected with either the pcDNA3 vector only or the indicated Flag-tagged PSMC3 (1–214) and siRNA-resistant PSMC3 (97–439) mutant. At 24 h after transfection, cells were split into two aliquots and were retransfected with control or PSMC3 siRNA. Cell lysates were analyzed by western blotting with anti-AGO2 and anti-GAPDH antibodies. m The interaction between AGO2 and USP14 is diminished in PSMC3-depletion cells. HeLa cells were cotransfected with the indicated plasmids. Immunoprecipitation assays were performed with anti-HA antibody and western blotting with anti-Flag antibody. All results are representative of three independent experiments

To determine whether PSMC3 depletion could promote AGO2 ubiquitination, PSMC3-specific or control siRNAs were transfected into HeLa cells with or without MG132. Consistent with our previous results, the knockdown of PSMC3 reduced AGO2 protein levels (Fig. 4a). However, when treated with MG132, this effect was eliminated (Fig. 5b). Ubiquitination assays (Fig. 5c) were similarly used to corroborate this result, suggesting that PSMC3 is involved in regulating the ubiquitin-mediated degradation of AGO2. Furthermore, the 4KR and 5KR mutants were completely resistant to degradation following PSMC3 depletion (Additional file 1: Fig. S5d). All these results indicate that PSMC3 depletion promotes ubiquitination of C-terminal lysine residues of AGO2 and, subsequently, the degradation of AGO2 in the cytoplasm by the proteasome.

To further explore the molecular mechanism by which PSMC3 regulates AGO2 ubiquitination, we predicted the PPI (Protein-Protein Interaction) network of PSMC3 by the STRING database (http://www.string-db.org) (Fig. 5d). By performing a Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis of the biological processes of these interacting proteins (Fig. 5e), the deubiquitinating enzyme USP14 attracted our attention, and a literature on a human deubiquitinating enzyme interaction network also supports our prediction[53]. USP14 is associated with proteasome regulatory particle and function in chain removal or editing of ubiquitinated proteasome substrates [54, 55]. Therefore, we hypothesized that PSMC3 acts in stabilizing the AGO2 protein by USP14. Co-IP confirmed that both PSMC3 and AGO2 interacted with USP14 (Fig. 5f, g), while the immunofluorescence assays indicated their colocalization in the cytoplasm (Additional file 1: Fig. S6a, b). We also constructed the truncated plasmids of USP14 (Additional file 1: Fig. S6c) and defined the interaction sites of PSMC3 and AGO2 on USP14 by co-IP (Additional file 1: Fig. S6d, e). We then tested the effect of USP14 on AGO2 protein levels, as well as on ubiquitination levels. It was found that USP14 could upregulate the protein levels of AGO2, and that this effect was offset when treated with MG132 (Fig. 5h). Meanwhile, ubiquitination assays showed that USP14 inhibited the ubiquitination of AGO2 (Fig. 5i). It has been reported that USP14 can regulate the proteasome activity in a manner independent of its deubiquitylase activity, which in turn affects the stability of some proteins [56]. To determine whether the deubiquitination of AGO2 by USP14 is dependent on its deubiquitylase activity, we examined the ubiquitination level of AGO2 protein after treating HeLa cells with IU1, an inhibitor of the enzymatic activity of USP14. The result showed that when the deubiquitylase activity of USP14 was inhibited, the ubiquitinated AGO2 protein was accumulated in the cells (Fig. 5j). This suggests that USP14 regulates the ubiquitination level of the AGO2 protein in a manner dependent on its deubiquitylase activity. To further elucidate whether the regulation of AGO2 by USP14 is dependent on PSMC3, HeLa cells were transfected with the indicated plasmids and then AGO2 protein levels were analyzed by western blotting assays. We found that this upregulation of USP14 on AGO2 was relieved upon PSMC3 knockdown (Fig. 5k). On the basis of the present results and our finding that the effect of PSMC3 on AGO2 stability is dependent on their interaction (Fig. 5l), we speculated that the role of PSMC3 might be to act as a bridge for AGO2 to bind to USP14. We then examined the binding of AGO2 to USP14 in PSMC3-depleted cells and found that their interaction was attenuated when PSMC3 was knocked down (Fig. 5m). Taken together, our results suggest that USP14 can deubiquitinate AGO2, and that this effect is dependent on PSMC3 as a bridge.

Given that inhibition of proteasome function led to the restoration of AGO2 expression in PSMC3-knockdown cells, we proposed that treatment of cells with the proteasome inhibitor MG132 could abrogate the effect of PSMC3 depletion on siRISC cleavage activities. We tested this hypothesis in either EGFP or EGFP-miR-21 (1× perfect) reporter systems and observed no significant difference in the siRISC activities of PSMC3-depleted and nondepleted cells upon the addition of MG132 (Additional file 1: Fig. S7a, b). Thus, MG132 treatment can rescue both siRNA and miRNA-guided siRISC cleavage activity in PSMC3-knockdown cells.

Discussion

Although small RNAs and AGO2 constitute the core endonucleolytic component of the RISC, other proteins might influence the RNA-induced gene silencing pathway through modifying or regulating AGO2 function. Herein we isolated PSMC3 as a novel AGO2-interacting protein in a yeast two-hybrid screen using the PIWI domain of AGO2 as bait, and N-terminal part of PSMC3 containing the coiled-coil motif is responsible for the interaction with AGO2. Further results showed that they interact in both nucleoplasm and cytoplasm in an RNA-independent manner. Moreover, our results also suggest that PSMC3 may promote RNAi and the functional evidence does support a role of PSMC3 in small RNA-induced mRNA cleavage by using the reporter systems. However, depletion of PSMC3 had no significant effect on translation suppression of reporter genes.

So how does PSMC3 regulate AGO2 and in turn affect RNAi? PSMC3 is a multifunctional protein. PSMC3 (also called HIV Tat-binding protein-1, TBP-1) was originally isolated as a protein that binds to the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) Tat transactivator and suppresses Tat-mediated transactivation [57]. It has been shown to regulate transcription, and the transcriptional activity of PSMC3 is dependent on its conserved nucleotide-binding motif and helicase domain [28]. In addition, PSMC3 could also control the amounts of proteins at post-translational level. As a component of the regulatory subunit of the 26S proteasome, PSMC3 seems not to have general effects on proteasome function but rather seems only to affect the stability of specific protein targets. Pollice et al. found that the interaction between PSMC3 and p14ARF protects the human oncosuppressor p14ARF from ubiquitin-independent proteasomal degradation [29, 36]. Therefore, we speculate that PSMC3 may affect the protein stability of AGO2.

In this study, we demonstrate that PSMC3 regulates stability of cytoplasmic AGO2 protein at posttranslational level. In PSMC3-depleted HeLa cells, the protein level of AGO2 were reduced, while its mRNA level was not correspondingly decreased. And overexpression of the PSMC3 N-terminus containing the coiled-coil motif overrode the decrease of AGO2 level, indicating the effect of PSMC3 on AGO2 protein amounts strictly requires their physical interaction. Treatment with cycloheximide demonstrated that the absence of PSMC3 shortened the half-life of AGO2 protein, and an increase of AGO2 protein turnover resulted in a decline of cytoplasmic AGO2 protein in HeLa cells.

There is some controversy about the degradation pathway of AGO2. Rybak et al. found that the E3 ubiquitin ligase mLin41 can mediate the ubiquitination of AGO2 [50]. While Martinez et al. demonstrated that AGO2 protein is degraded in lysosomes in mouse embryonic cells [58]. Our results suggest that AGO2 is degraded via the proteasome pathway and there are four ubiquitination sites present at the C-terminus of AGO2: K607, K608, K820, and K844. We thus hypothesized that PSMC3 maintains the stability of AGO2 by preventing its ubiquitination. The results showed that depletion of PSMC3 enhanced AGO2 ubiquitination, leading to AGO2 degradation through the 26S proteasome. But what is the mechanism by which PSMC3 prevents AGO2 ubiquitination? Are other proteins involved in this process?

The STRING database predicted USP14 that may interact with PSMC3. USP14 is associated with proteasome regulatory particle and function in chain removal or editing of ubiquitinated proteasome substrates [54, 55]. Loss of USP14 in mammalian cells or Ubp6 in yeast results in increased degradation of ubiquitinated proteins and reduction of free ubiquitin molecules, indicating that USP14 is required for the recycling of ubiquitin molecules [59, 60]. Prion proteins can be regulated by USP14, and intracellular prion protein levels are reduced when USP14 catalytic activity is inhibited [61]. Our results demonstrated that PSMC3 and AGO2 both interact with USP14 in cytoplasm and USP14 can regulate the deubiquitination of AGO2 through its deubiquitinase activity. Moreover, this effect requires the involvement of PSMC3, indicating PSMC3 acts in stabilizing the AGO2 protein by USP14.

The present study provides a model for PSMC3 function in AGO2-dependent RNAi as shown in Fig. 6. The ubiquitinated AGO2 protein is recruited to the proteasome 19S regulatory subunit by interacting with PSMC3 and then interacts with USP14, which binds 26S proteasome reversibly to form AGO2–PSMC3–USP14 complex. Thereafter, PSMC3 assists with USP14 in exposing its active center and promotes USP14-mediated deubiquitination of AGO2 so that AGO2 proteins can be released from the 26S proteasome and function in an effective RNAi. Otherwise, the ubiquitinated AGO2 is degraded in the 20S catalytic subunit after defolding and displacement. On the basis of this model, it will be of interest to investigate how changes in PSMC3 levels correlate with AGO2 levels during physiological and pathological processes.

A model for PSMC3 function in AGO2-dependent RNAi. The ubiquitinated AGO2 protein is recruited to the proteasome 19S regulatory subunit by interacting with PSMC3 and then interacts with USP14, which binds 26S proteasome reversibly to form AGO2–PSMC3–USP14 complex. Thereafter, PSMC3 assists with USP14 in exposing its active center and promotes USP14 deubiquitination of AGO2 so that AGO2 proteins can be released from the 26S proteasome and function in an effective RNAi. Otherwise, the ubiquitinated AGO2 is degraded in the 20S catalytic subunit after defolding and displacement

However, there are still many unanswered questions. Regarding the fact that PSMC3 depletion affects siRISC activity but not miRISC activity, the same is true for Qi et al. Their results have shown that type I collagen prolyl-4-hydroxylase [C-P4H(I)] physically interacts with AGO2 and catalyzes proline hydroxylation of the AGO2 protein. Depletion of C-P4H(I) subunits reduced the stability of AGO2 resulting in impairment of small-RNA-programmed siRISC activity, but miRISC activity was not altered upon C-P4H(I) knockdown[49]. Since the only protein involved in targeted cleavage is AGO2 and all AGOs can be involved in translational repression, we speculate that this result may be due to the compensatory effect of other AGO proteins. For PSMC3 affecting the protein levels of cytoplasmic AGO2 rather than nuclear AGO2, we found that USP14 was not localized in the nucleus through the Uniprot database (https://www.uniprot.org/), and our results confirmed this (Additional file 1: Fig. S8). However, these are just our speculations, and more studies are needed to test these hypotheses.

Conclusion

Our findings demonstrate that PSMC3 plays an important role in assisting USP14 to deubiquitinate AGO2, which in turn maintains the stability of AGO2 to ensure effective RNAi.

Availability of data and materials

All relevant data supporting the findings of this study are available in the article, Additional files, or from the corresponding authors on reasonable request. BDM-PUB is a web site for protein ubiquitination sites prediction (http://bdmpub.biocuckoo.org/prediction.php). UbPred is a web site for protein ubiquitination sites prediction (http://www.ubpred.org/). STRING is a database for protein association networks analysis (http://www.string-db.org). UniProt is a database of protein information (http://www.uniprot.org/)

Abbreviations

- AAA:

-

ATPases Associated with a wide variety of cellular Activities

- AGO2:

-

Argonaute 2

- C-P4H(I):

-

Type I collagen prolyl-4-hydroxylase

- CXCR4:

-

Chemokine (C–X–C motif) receptor 4

- DFFA:

-

DNA fragmentation factor subunit alpha

- GO:

-

Gene Ontology

- HIV-1:

-

Human immunodeficiency virus type 1

- PACT:

-

Protein activator of the interferon induced protein kinase

- PPI:

-

Protein–protein interaction

- PSMC3:

-

Proteasome 26S subunit, ATPase, 3

- RBBP6:

-

Retinoblastoma binding protein 6

- RNAi:

-

RNA interference

- RISC:

-

RNA-induced silencing complex

- USP14:

-

Ubiquitin specific peptidase 14

References

Bohmert K, Camus I, Bellini C, Bouchez D, Caboche M, Benning C. AGO1 defines a novel locus of Arabidopsis controlling leaf development. EMBO J. 1998;17(1):170–80. https://doi.org/10.1093/emboj/17.1.170.

Sasaki T, Shiohama A, Minoshima S, Shimizu N, Sasaki T, Shiohama A, Minoshima S. Shimizu N Identification of eight members of the Argonaute family in the human genome. Genomics. 2003;82(3):323–30.

Höck J, Meister G. The Argonaute protein family. Genome Biol. 2008;9(2):210. https://doi.org/10.1186/gb-2008-9-2-210.

Meister G. Argonaute proteins: functional insights and emerging roles. Nat Rev Genet. 2013;14(7):447–59. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrg3462.

Liu J, Carmell MA, Rivas FV, Marsden CG, Thomson JM, Song JJ, et al. Argonaute2 is the catalytic engine of mammalian RNAi. Science. 2004;305(5689):1437–41. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1102513.

Tolia NH, Joshua-Tor L. Slicer and the argonautes. Nat Chem Biol. 2007;106(1):36–43.

Song JJ, Smith SK, Hannon GJ, Joshua-Tor L. Crystal structure of Argonaute and its implications for RISC slicer activity. Science. 2004;305(5689):1434–7. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1102514.

Schirle NT, MacRae IJ. The crystal structure of human Argonaute2. Science. 2012;336(6084):1037–40. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1221551.

Jinek M, Doudna JA. A three-dimensional view of the molecular machinery of RNA interference. Nature. 2009;457(7228):405–12. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature07755.

Frank F, Sonenberg N, Nagar B. Structural basis for 5′-nucleotide base-specific recognition of guide RNA by human AGO2. Nature. 2010;465(7299):818–22. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature09039.

Janowski BA, Huffman KE, Schwartz JC, Ram R, Nordsell R, Shames DS, et al. Involvement of AGO1 and AGO2 in mammalian transcriptional silencing. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2006;13(9):787–92. https://doi.org/10.1038/nsmb1140.

Ameyar-Zazoua M, Rachez C, Souidi M, Robin P, Fritsch L, Young R, et al. Argonaute proteins couple chromatin silencing to alternative splicing. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2012;19(10):998–1004. https://doi.org/10.1038/nsmb.2373.

Batsché E, Ameyar-Zazoua M. The influence of Argonaute proteins on alternative RNA splicing. Wiley Interdiscip Rev RNA. 2015;6(1):141–56. https://doi.org/10.1002/wrna.1264.

Fu Y, Chen L, Chen C, Ge Y, Kang M, Song Z, et al. Crosstalk between alternative polyadenylation and miRNAs in the regulation of protein translational efficiency. Genome Res. 2018;28(11):1656–63. https://doi.org/10.1101/gr.231506.117.

Berrens RV, Andrews S, Spensberger D, Santos F, Dean W, Gould P, et al. An endosiRNA-based repression mechanism counteracts transposon activation during global DNA demethylation in embryonic stem cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2017;21(5):694–703.e7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stem.2017.10.004.

Iwasaki S, Tomari Y. Argonaute-mediated translational repression (and activation). Fly. 2009;3(3):204–6.

Kim BS, Im YB, Jung SJ, Park CH, Kang SK. Argonaute2 regulation for K channel-mediated human adipose tissue-derived stromal cells self-renewal and survival in nucleus. Stem Cells Dev. 2012;21(10):1736–48. +https://doi.org/10.1089/scd.2011.0388.

Wilson RC, Doudna JA. Molecular mechanisms of RNA interference. Ann Rev Biophys. 2013;42:217–39. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-biophys-083012-130404.

Bartoszewski R, Sikorski AF. Editorial focus: entering into the non-coding RNA era. Cell Mol Biol Lett. 2018;23:45. https://doi.org/10.1186/s11658-018-0111-3.

Wang Y, Sheng G, Juranek S, Tuschl T, Patel DJ. Structure of the guide-strand-containing Argonaute silencing complex. Nature. 2008;456(7219):209–13. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature07315.

Kiriakidou M, Tan GS, Lamprinaki S, De Planell-Saguer M, Nelson PT, Mourelatos Z. An mRNA m7G cap binding-like motif within human Ago2 represses translation. Cell. 2007;129(6):1141–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.016.

De N, Macrae IJ. Purification and assembly of human Argonaute, Dicer, and TRBP complexes. Methods Mol Biol (Clifton NJ). 2011;725:107–19. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-61779-046-1_8.

Meister G, Landthaler M, Peters L, Chen PY, Urlaub H, Lührmann R, et al. Identification of novel Argonaute-associated proteins. Curr Biol. 2005;15(23):2149–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2005.10.048.

Peters L, Meister G. Argonaute proteins: mediators of RNA silencing. Mol Cell. 2007;26(5):611–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2007.05.001.

Tahbaz N, Kolb FA, Zhang H, Jaronczyk K, Filipowicz W, Hobman TC. Characterization of the interactions between mammalian PAZ PIWI domain proteins and Dicer. EMBO Rep. 2004;5(2):189–94. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.embor.7400070.

Lima WF, Wu H, Nichols JG, Sun H, Murray HM, Crooke ST. Binding and cleavage specificities of human Argonaute2. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(38):26017–28. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M109.010835.

Lian SL, Li S, Abadal GX, Pauley BA, Fritzler MJ, Chan EK. The C-terminal half of human Ago2 binds to multiple GW-rich regions of GW182 and requires GW182 to mediate silencing. RNA (New York NY). 2009;15(5):804–13. https://doi.org/10.1261/rna.1229409.

Ohana B, Moore PA, Ruben SM, Southgate CD, Green MR, Rosen CA. The type 1 human immunodeficiency virus Tat binding protein is a transcriptional activator belonging to an additional family of evolutionarily conserved genes. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90(1):138–42. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.90.1.138.

Pollice A, Sepe M, Villella VR, Tolino F, Vivo M, Calabrò V, et al. TBP-1 protects the human oncosuppressor p14ARF from proteasomal degradation. Oncogene. 2007;26(35):5154–62. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.onc.1210313.

Goodkin ML, Ting AT, Blaho JA. NF-kappaB is required for apoptosis prevention during herpes simplex virus type 1 infection. J Virol. 2003;77(13):7261–80. https://doi.org/10.1128/jvi.77.13.7261-7280.2003.

Huang W, Wang SL, Lozano G, de Crombrugghe B. cDNA library screening using the SOS recruitment system. BioTechniques. 2001;30(1):94–8. https://doi.org/10.2144/01301st06.

Lee Y, Hur I, Park SY, Kim YK, Suh MR, Kim VN. The role of PACT in the RNA silencing pathway. EMBO J. 2006;25(3):522–32. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.emboj.7600942.

Höck J, Weinmann L, Ender C, Rüdel S, Kremmer E, Raabe M, et al. Proteomic and functional analysis of Argonaute-containing mRNA–protein complexes in human cells. EMBO Rep. 2007;8(11):1052–60. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.embor.7401088.

Yi T, Arthanari H, Akabayov B, Song H, Papadopoulos E, Qi HH, et al. eIF1A augments Ago2-mediated Dicer-independent miRNA biogenesis and RNA interference. Nat Commun. 2015;6:7194. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncomms8194.

Bottini S, Hamouda-Tekaya N, Mategot R, Zaragosi LE, Audebert S, Pisano S, et al. Post-transcriptional gene silencing mediated by microRNAs is controlled by nucleoplasmic Sfpq. Nat Commun. 2017;8(1):1189. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-017-01126-x.

Pollice A, Nasti V, Ronca R, Vivo M, Lo Iacono M, Calogero R, et al. Functional and physical interaction of the human ARF tumor suppressor with Tat-binding protein-1. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(8):6345–53. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M310957200.

Ahlenstiel CL, Lim HG, Cooper DA, Ishida T, Kelleher AD, Suzuki K. Direct evidence of nuclear Argonaute distribution during transcriptional silencing links the actin cytoskeleton to nuclear RNAi machinery in human cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012;40(4):1579–95. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkr891.

Gagnon KT, Corey DR. Argonaute and the nuclear RNAs: new pathways for RNA-mediated control of gene expression. Nucleic acid therapeutics. 2012;22(1):3–16. https://doi.org/10.1089/nat.2011.0330.

Ohrt T, Muetze J, Svoboda P, Schwille P. Intracellular localization and routing of miRNA and RNAi pathway components. Curr Top Med Chem. 2012;12(2):79–88. https://doi.org/10.2174/156802612798919132.

Gagnon KT, Li L, Janowski BA, Corey DR. Analysis of nuclear RNA interference in human cells by subcellular fractionation and Argonaute loading. Nat Protoc. 2014;9(9):2045–60. https://doi.org/10.1038/nprot.2014.135.

Corn PG, McDonald ER 3rd, Herman JG, El-Deiry WS. Tat-binding protein-1, a component of the 26S proteasome, contributes to the E3 ubiquitin ligase function of the von Hippel-Lindau protein. Nat Genet. 2003;35(3):229–37. https://doi.org/10.1038/ng1254.

Rivas FV, Tolia NH, Song JJ, Aragon JP, Liu J, Hannon GJ, et al. Purified Argonaute2 and an siRNA form recombinant human RISC. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2005;12(4):340–9. https://doi.org/10.1038/nsmb918.

Landthaler M, Yalcin A, Tuschl T. The human DiGeorge syndrome critical region gene 8 and its D. melanogaster homolog are required for miRNA biogenesis. Curr Biol. 2004;14(23):2162–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2004.11.001.

Meister G, Landthaler M, Patkaniowska A, Dorsett Y, Teng G, Tuschl T. Human Argonaute2 mediates RNA cleavage targeted by miRNAs and siRNAs. Mol Cell. 2004;15(2):185–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2004.07.007.

Doench JG, Petersen CP, Sharp PA. siRNAs can function as miRNAs. Genes Dev. 2003;17(4):43–42. https://doi.org/10.1101/gad.1064703.

Liu J, Rivas FV, Wohlschlegel J, Yates JR 3rd, Parker R, Hannon GJ. A role for the P-body component GW182 in microRNA function. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7(12):1261–6. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncb1333.

Zhou R, Hotta I, Denli AM, Hong P, Perrimon N, Hannon GJ. Comparative analysis of Argonaute-dependent small RNA pathways in Drosophila. Mol Cell. 2008;32(4):592–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.molcel.2008.10.018.

Qi HH, Ongusaha PP, Myllyharju J, Cheng D, Pakkanen O, Shi Y, et al. Prolyl 4-hydroxylation regulates Argonaute 2 stability. Nature. 2008;455(7211):421–4. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature07186.

Zeng Y, Sankala H, Zhang X, Graves PR. Phosphorylation of Argonaute 2 at serine-387 facilitates its localization to processing bodies. Biochem J. 2008;413(3):429–36. https://doi.org/10.1042/bj20080599.

Rybak A, Fuchs H, Hadian K, Smirnova L, Wulczyn EA, Michel G, et al. The let-7 target gene mouse lin-41 is a stem cell specific E3 ubiquitin ligase for the miRNA pathway protein Ago2. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11(12):1411–20. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncb1987.

Chinen M, Lei EP. Drosophila Argonaute2 turnover is regulated by the ubiquitin proteasome pathway. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2017;483(3):951–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbrc.2017.01.039.

Zhang H, Zhao X, Guo Y, Chen R, He J, Li L, et al. Hypoxia regulates overall mRNA homeostasis by inducing Met1-linked linear ubiquitination of AGO2 in cancer cells. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):5416. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-25739-5.

Sowa ME, Bennett EJ, Gygi SP, Harper JW. Defining the human deubiquitinating enzyme interaction landscape. Cell. 2009;138(2):389–403. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2009.04.042.

Hu M, Li P, Song L, Jeffrey PD, Chenova TA, Wilkinson KD, et al. Structure and mechanisms of the proteasome-associated deubiquitinating enzyme USP14. EMBO J. 2005;24(21):3747–56. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.emboj.7600832.

Sharma A, Alswillah T, Kapoor I, Debjani P, Willard B, Summers MK, et al. USP14 is a deubiquitinase for Ku70 and critical determinant of non-homologous end joining repair in autophagy and PTEN-deficient cells. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020;48(2):736–47. https://doi.org/10.1093/nar/gkz1103.

Hanna J, Hathaway NA, Tone Y, Crosas B, Elsasser S, Kirkpatrick DS, et al. Deubiquitinating enzyme Ubp6 functions noncatalytically to delay proteasomal degradation. Cell. 2006;127(1):99–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2006.07.038.

Nelbock P, Dillon PJ, Perkins A, Rosen CA. A cDNA for a protein that interacts with the human immunodeficiency virus Tat transactivator. Science. 1990;248(4963):1650–3. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.2194290.

Martinez NJ, Chang HM, Borrajo Jde R, Gregory RI. The co-chaperones Fkbp4/5 control Argonaute2 expression and facilitate RISC assembly. RNA (New York NY). 2013;19(11):1583–93. https://doi.org/10.1261/rna.040790.113.

Leggett DS, Hanna J, Borodovsky A, Crosas B, Schmidt M, Baker RT, et al. Multiple associated proteins regulate proteasome structure and function. Mol Cell. 2002;10(3):495–507. https://doi.org/10.1016/s1097-2765(02)00638-x.

Chernova TA, Allen KD, Wesoloski LM, Shanks JR, Chernoff YO, Wilkinson KD. Pleiotropic effects of Ubp6 loss on drug sensitivities and yeast prion are due to depletion of the free ubiquitin pool. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(52):52102–15. https://doi.org/10.1074/jbc.M310283200.

Homma T, Ishibashi D, Nakagaki T, Fuse T, Mori T, Satoh K, et al. Ubiquitin-specific protease 14 modulates degradation of cellular prion protein. Sci Rep. 2015;5:11028. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep11028.

Acknowledgements

We thank all the participants in this study.

Funding

This work was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Tianjin (08JCZDJC23300, 09JCZDJC17500).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

YJ and XQZ conceived and designed the experiments. YJ, JNZ and TY performed the experiments. XZ, XZQ, TXH and ZYJ participated in data analysis. YJ and XQZ prepared the manuscript. The authors discussed the results and implications throughout. All authors have read and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

All authors declare there is no conmpeting interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Additional file 1

: FigureS1. PSMC3 interacts with AGO2. Figure S2. PSMC3 is required for mRNA cleavage rather than translational repression. Figure S3. Depletion of PSMC3 by siRNAs. FigureS4. PSMC3 is essential to maintain AGO2 protein levels. Figure S5.Determination of the AGO2 ubiquitination sites. Figure S6. PSMC3 and AGO2 both interact with USP14. Figure S7. Proteasome inhibition abrogates the effect of PSMC3 depletion on siRISC activities. Figure S8. USP14 protein is localized in cytoplasm.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jia, Y., Zhao, J., Yu, T. et al. PSMC3 promotes RNAi by maintaining AGO2 stability through USP14. Cell Mol Biol Lett 27, 111 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s11658-022-00411-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s11658-022-00411-y