Abstract

Background

There are no robust population-based Australian data on prevalence and attributed burden of migraine and medication-overuse headache (MOH) data. In this pilot cross-sectional study, we aimed to capture the participation rate, preferred response method, and acceptability of self-report questionnaires to inform the conduct of a future nationwide migraine/MOH epidemiological study.

Methods

We developed a self-report questionnaire, available in hard-copy and online, including modules from the Headache-Attributed Restriction, Disability, Social Handicap and Impaired Participation (HARDSHIP) questionnaire, the Eq. 5D (quality of life), and enquiry into treatment gaps. Study invitations were mailed to 20,000 randomly selected households across Australia’s two most populous states. The household member who most recently had a birthday and was aged ≥ 18 years was invited to participate, and could do so by returning a hard-copy questionnaire via reply-paid mail, or by entering responses directly into an online platform.

Results

The participation rate was 5.0% (N = 1,000). Participants’ median age was 60 years (IQR 44–71 years), and 64.7% (n = 647) were female. Significantly more responses were received from areas with relatively older populations and middle-level socioeconomic status. Hard copy was the more commonly chosen response method (n = 736). Females and younger respondents were significantly more likely to respond online than via hard-copy.

Conclusions

This pilot study indicates that alternative methodology is needed to achieve satisfactory engagement in a future nationwide migraine/MOH epidemiological study, for example through inclusion of migraine screening questions in well-resourced, interview-based national health surveys that are conducted regularly by government agencies. Meanwhile, additional future research directions include defining and addressing treatment gaps to improve migraine awareness, and minimise under-diagnosis and under-treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Worldwide, epidemiological studies have consistently identified migraine and medication-overuse headache (MOH) as highly prevalent and disabling headache disorders [1, 2], but there are no robust population-based Australian data. Australian epidemiological studies of migraine have so far been limited to certain age groups, geographical areas, or care settings [3,4,5]. Other Australian studies that report migraine prevalence have not been designed with the primary intention of collecting these data, and therefore have limited generalisability across the general population [6,7,8]. No formal study of MOH has been undertaken in Australia. Extrapolating data from international studies does not accurately reflect Australia’s unique population and healthcare system.

Population-based studies within Australia are therefore needed to determine the scope and scale of headache disorders, especially migraine and MOH, as these are the most likely major public health issues [9]. Such studies are ideally conducted through face-to-face engagement with participants by trained interviewers [10], but this is resource intensive. Our purpose here, prior to undertaking a definitive study, was to assess the feasibility of using mailed questionnaires as a much less costly alternative to establish the prevalence and burden of migraine and probable MOH (pMOH) in Australia.

Methods

The study design was a cross-sectional enquiry by a questionnaire mailed to addresses selected randomly to be representative of Australia’s population aged 18 years or older. The methodology was informed by the principles and recommendations [10] set out by the Global Campaign against Headache [11].

Aims

The overall purpose was to inform the design, logistic planning, and effective conduct of a future nationwide headache epidemiological study. The aims of this pilot study were to: (1) establish the participation rate, preferred response method (paper-based vs. online), and acceptability of mailed self-report study questionnaires; and (2) provide estimates of prevalence, burden, and treatment gaps to inform power calculations in a future study.

Selection of postal addresses to represent the general population

We conducted the study in New South Wales and Victoria, the two most populous states in Australia.

We used a two-stage cluster sampling approach to implement equal probability sampling for households. We first sampled 100 local government areas (LGAs) from the 207 LGAs in Victoria and New South Wales using the probability proportional to size with probability minimum replacement sampling method, where the probability of selecting an LGA was proportionate to the total number of private dwellings in the LGA. Depending on the number of private dwellings in the LGA, it was possible that large LGAs would be sampled more than once and each sample was considered an independent cluster. The maximum number of times an LGA could be sampled was restricted by the probability minimum replacement method. In the second stage, 200 individual households in each sampled LGA were selected using simple random sampling method.

HopeWiser, a company providing an Australia Post-accredited address matching approval system, provided the addresses of 20,000 randomly selected households from the study LGAs across Victoria and New South Wales. HopeWiser extracted all valid addresses (i.e., those that had been identified on more than one source for the GeoCoded National Address File dataset), then used software to match these addresses against Australia Post’s Postal Address File (a highly sampled, mature dataset, having been commercially available for > 23 years with monthly updates). The resultant matches were enhanced by markers for ‘residential, ‘non-residential’, ‘deliverable’, and ‘non-deliverable’ provided by Australia Post.

This process captured the vast majority of deliverable residential addresses in Australia with high reliability in terms of completeness and accuracy (< 2% of households use postal services such as roadside mailbags or post office boxes rather than a letter box at their residential address).

Questionnaire

We used validated instruments where possible for each section of our study questionnaire (Appendix 1).

The core of the present questionnaire utilised modules from the Headache-Attributed Restriction, Disability, Social Handicap and Impaired Participation (HARDSHIP) questionnaire [11], which has already been used in > 20 countries to measure headache prevalence and attributed burden in non-clinical settings [12]. Although only initially validated for face-to-face administration by trained lay interviewers, HARDSHIP has also been adapted as a self-report instrument, in the EUROLIGHT questionnaire [13]. Enquiry into basic demographic data (age, gender, postal/zip code, preferred language, Aboriginal and/or Torres Strait Islander status) was followed by headache screening questions (ever, and in the preceding year) and diagnostic questions based on ICHD-3. We used the Headache-Attributed Lost Time questionnaire (HALT) for capturing headache-attributed lost productivity [14], and the generic health-related quality of life (HR-QOL) EQ-5D-5 L instrument. Further questions addressed healthcare utilisation (headache-related outpatient visits, tests, and emergency department and hospital attendances within the previous year), medications (type and frequency of symptomatic headache medication used in the preceding 31 days, and currently used preventative medications), out of pocket costs (headache-related healthcare expenses within the previous three months, not covered by health insurance), barriers to accessing care (questions on self-recognition of migraine, diagnosis ever of migraine from a healthcare provider, difficulties in accessing a healthcare provider for headache, and any previous cessations of symptomatic, and/or, preventative migraine therapy, with the reasons why, all based on previous studies [15, 16]), and informal care needs (questions from European HIROZON-funded studies by co-author ZA on unpaid care from family or friends, and, if so, how many hours per week [not yet published]).

Sample size estimation

We estimated the sample size needed to establish migraine prevalence as N = 1,750, basing the calculation on the estimated prevalence of migraine for Australia of 0.18 from the Institute of Health Metrics and Evaluation [17], with a relative 10% margin for error. We estimated the number of mail outs needed as N = 19,445, assuming that 90% of households would have at least one eligible adult (see below), but a response rate of only 10%. We inflated this to N = 20,000 in anticipation that some study letters would inadvertently be sent to non-deliverable addresses.

Mail out

We outsourced the mail out (including printing invitation letters and questionnaires, addressing envelopes, inserting reply-paid envelopes, and oversight of the process) to Direct Mail Solutions, a well-established company.

Inclusion criteria

Potentially eligible participants were adults aged 18 years and over. From these, only the person who had most recently had their birthday was asked to respond.

Respondents needed to opt in as participants within the study timeframe, either by entering data directly into the secure online Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) platform, accessed via a QR code or weblink included in the study invitation letter, or by returning their hard-copy questionnaires by reply-paid post, with researchers entering the responses into the platform.

Please see Fig. 1 for the study workflow.

Data management

Study data were collected and managed using the REDCap electronic data capture tool hosted and managed by Helix (Monash University) [18, 19]. REDCap is a secure, web-based software platform designed to support data capture for research studies, providing: (1) an intuitive interface for data capture; (2) audit trails for tracking data manipulation and export procedures; (3) automated export procedures for seamless data downloads to common statistical packages; and (4) procedures for data integration and interoperability with external sources.

Diagnoses

Participants reporting any headache within the preceding year were considered to have an active headache disorder, with all others considered to be headache-free. Diagnoses were made during analysis, and not at the time of data collection, using the HARDSHIP algorithm [11], applied to the most bothersome headache type when more than one type was reported. The algorithm first identified those reporting headache on ≥ 15 days/month, diagnosing pMOH when acute medication use on ≥ 10 days/month was also reported and otherwise “other headache on ≥ 15 days/month” (other H15+). In all others with active headache disorder (episodic headache), the algorithm diagnosed, in hierarchical order, definite migraine, definite TTH, probable migraine, probable TTH, and unclassified. Used in this way, the algorithm identifies migraine (definite or probable) with a sensitivity > 70% and a specificity > 70% [12].

Data analysis

Analysis included all participants who answered at least one question.

Participation rate and preferred response method were assessed with reference to age, gender and state. Categorical variables were summarised using frequency and percentage. Continuous variables with approximately normal distribution were summarised using mean and standard deviation (SD), or, otherwise, median and interquartile range (IQR). Prevalence estimates of each headache type were adjusted according to the age and gender distributions of each state. A bootstrapping method with 1,000 iterations was used to estimate variances and calculate 95% confidence intervals (CIs). In the analysis, we combined definite and probable cases of migraine, as well as definite and probable cases of TTH, respectively.

Missing data were summarised using frequency and percentage. The missingness of data was assessed using Little’s chi-squared test for missing completely at random test or covariate-dependent missingness. Since missingness of data was found to be dependent on age, gender, and socioeconomic status (represented in Index of Relative Socio-economic Advantage and Disadvantage [IRSAD] quintile), these covariates were adjusted in the analyses, where applicable.

Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. Holm-Bonferroni’s method was used to control for 5% family-wise error rate in subgroup pairwise comparison, if applicable. All statistical analyses were performed using Stata version 16.1 (StataCorp).

Ethics

The study was granted multisite ethics approval by the Alfred Hospital Ethics Committee (HREC reference: 87,013, Local number: 305/22). Governance approval was granted by the Offices for Research at the individual study sites.

Participation was voluntary, requiring respondents to opt in, with consent therefore presumed.

Only non-identifiable data were captured and therefore participants could not be identified from their responses.

Results

The study launched on 27 January 2023, mail out was completed over a one-week period, and the study closed to responses on 31 March 2023.

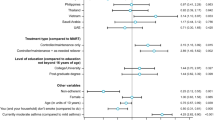

Respondent characteristics

A total of 1,000 eligible responses were received, the majority (n = 736, 73.6%) via reply-paid mail (hard-copy questionnaires), with females and younger age groups significantly more likely to respond online (Table 1). The overall participation rate was therefore 5.0% (1,000/20,000). Participation rates were higher from LGAs with relatively older populations (for every 10 years increase in age, RoM = 1.04, 95% CI: 1.02–1.05, p < 0.001). LGAs with middle-level socioeconomic status (IRSAD third quintile) had higher participation rates than those with lower or higher socioeconomic status after adjustment for age (Table 2). Overall, participants’ median age was 60 years (IQR 44–71), and 64.7% were female. English was the most common language spoken at home (93%). Only 1.5% of participants identified as Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander people (Table 1). These characteristics differed substantially from those of the general Australian population (median age 38 years, 50.7% female, 72% speaking only English at home and 3.2% identifying as Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander people [20]).

Diagnoses

Of the 1,000 eligible responses received, 22 participants were excluded from analysis, six because they reported headache-ever but did not answer whether they had headache in the last 12 months, and 16 because they did not answer the questionnaire. Among 978 participants with valid HARDSHIP questionnaire responses, the vast majority (n = 946, 96.7%) reported headache-ever (lifetime prevalence), and most (n = 754, 77.1%) reported an active headache disorder (1-year prevalence). The raw 1-year prevalences for each headache type were 3.6% (n = 35) for pMOH, 6.8% (n = 66) for other H15+, 7.8% (n = 76) for definite migraine, 13.6% (n = 133) for definite TTH, 22.6% (n = 221) for probable migraine, 15.8% (n = 154) probable TTH, and 7.1% (n = 69) for unclassified headache. Raw prevalences by age, gender, and State are presented in Table 3.

Adjusted for sampling weights, age, gender, and State, 1-year prevalence estimates for each headache type were 3.5% (95% CI: 2.2–5.5%) for pMOH, 8.6% (95% CI: 6.6–11.0%) for other H15+, 35.0% (95% CI: 30.9–39.2%) for definite + probable migraine, and 31.0% (27.3–34.9%) for definite + probable TTH, with 6.3% unclassified headache.

Further analyses were not considered appropriate in view of the very low participation rate.

Discussion

This pilot study revealed that mailed self-reporting headache epidemiological questionnaires yielded low participant engagement, indicating that alternative methods are needed for collecting reliable data from the Australian general population. The bias towards those living with bothersome headache was almost inevitable, given the participating proportion of only 5.0%. The high median age of 60 years and the high female proportion (65%) were clear evidence of bias. The estimated 1-year prevalence of migraine, more than double that expected from estimates in other high-income countries [2, 21], was almost certainly a result of such bias. Therefore, while the data gathered from this study represent the largest body of evidence relating to migraine in the adult Australian general population to date, the low response rate introduces a high risk of non-response bias and selection bias, which means all other findings are of highly questionable value.

In anticipation of the possibility of a low participation rate, we took a number of pre-emptive measures: we offered both hard-copy and online versions of the questionnaire; engaged a consumer advocate to inform the construction of an appealing study invitation letter that was in colour, included logos of participating institutions, photographs of the researchers, and clear explanation of why the study was important; created a study webpage hosted on an institutional website to provide background information about the study and the researchers involved; created a Twitter/X account (@aheadstudy2022) to keep members of the public informed on study progress; and created a study video that was displayed on the study webpage and on the landing page of the online questionnaire to explain the study in an engaging visual format. The study launch attracted substantial media attention, with the lead investigator (EF) invited to promote it on nine radio stations across the country, achieving two primetime news bulletins, and it appeared in print in Australia’s most widely read newspaper. All, it seems, were insufficient.

Our participation rate was lower than those achieved by other international population-based epidemiology studies using mailed questionnaires in high-income countries [22]. The EUROLIGHT project was a survey-based headache epidemiology study conducted across 10 European countries using different sampling methods [22]. As in our study, Germany and Italy distributed study questionnaires to the general population via regular post, requested return via reply-paid envelopes, and sent no reminders. Participation rates were 11.3% and 14.3%, respectively. Luxembourg also had similar methodology with the exception that a reminder was sent to non-responders one month later; their responder rate was 31.1%. One explanation for the higher participation rates from these countries was that their study questionnaires were addressed to specific individuals, who had been selected from lists provided by local authorities to ensure representative sampling of the general population. Our study addressed letters impersonally ‘To the householder’. We were unable to access a list of individuals’ names and addresses that were representative of the general population as the responsible government department was overseeing the federal election at the time of our study. In addition to addressing questionnaires to specific individuals and introducing follow-up approaches (as done in the EUROLIGHT project), future research may need to consider other tactics, such as pre-notifications, so that arrival of the questionnaire is expected, with its purpose already understood, incentives to respond (monetary or non-monetary, as used in the Australian Longitudinal Study on Women’s Health) [23], remainders chasing non-responders, and availability of other language versions of the questionnaire. Each of these will increase the resources needed, and none is guaranteed to increase the participating proportion, or improve reliability (each may introduce other biases). A shorter questionnaire may yield a higher response rate [24], but limit the value of the study.

Very clearly, a different design will be needed for a nationwide epidemiological study. For many diseases, nationwide prevalence data can be drawn from administrative datasets. For example, acute stroke in almost all cases results in hospital contact, and multiple sclerosis has disease-specific therapies. Prevalence of these disorders may reasonably be inferred from hospital discharge codes and prescription datasets, respectively. Migraine attacks rarely present to hospital, and only 22% of specialists, such as neurologists, have used the national healthcare record that aims to store key health information [25]. In Australia, most oral migraine preventative drugs must be prescribed privately, since the universal pharmaceutical insurance scheme (Australian Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme) does not list migraine as an indication for relevant antiseizure medications, mood stabilisers, antihypertensives, and so on, and private script data are not available for data linkage studies [26]. Migraine-specific therapies, such as triptans and anti-CGRP monoclonal antibodies, are included in Australia’s Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme, but their use is restricted to people who meet specific inclusion and exclusion criteria. For all these reasons, a data linkage approach would grossly underestimate migraine prevalence, and would not account for undiagnosed cases of migraine in the community. Other countries have administered structured or semi-structured headache epidemiological questionnaires via telephone with trained lay reviewers [27]. However, in Australia the publicly available record of telephone numbers does not include residential addresses that have ‘opted out’ of listing, potentially resulting in a non-representative sample, and it might be anticipated that the vast majority of study calls, coming from an unknown number, would be rejected by prospective participants [28]. Another approach would be to compile a study sample that was demographically and geographically representative of the general population via market research companies [29]. Such a sample might receive monetary or other incentives to complete questionnaires, improving response rates but also introducing bias among those choosing to participate.

Following on from our study, it would seem the most pragmatic approach for collecting Australian headache prevalence data would be to include validated diagnostic questions in an upcoming cycle of the National Health Survey (NHS) [7]. The NHS is conducted every few years by the Australian Bureau of Statistics. Over a few weeks’ period, trained interviewers conduct face-to-face semi-structured interviews with > 20,000 households that are demographically representative of the general population. This type of study is well outside the budget of most research groups. In recognition of this, the NHS selects a limited number of conditions for specific examination with each cycle. Given the difficulties in establishing prevalence of headache types (e.g., migraine, pMOH) through self-report questionnaires, as comprehensively demonstrated in our study, and by other methods, coupled with the substantial burden of headache evidenced elsewhere, there is an extremely compelling case to include at least migraine in an upcoming NHS.

Limitations

First and foremost, as already discussed, this study was limited by the low participation rate, with inevitable biases. The findings with regard to prevalence are neither reliable nor generalizable. This study was, nonetheless, informative as a pilot study to test the methodology before investment of resources in a definitive study.

Conclusion

The mailed self-report questionnaire had a very low participation rate, clearly indicating that it would not be a suitable methodology for a future nationwide epidemiological study. Instead, these findings strongly support the inclusion of dedicated migraine diagnostic questions in an epidemiological study with higher participant engagement, for example, the National Health Survey. The arguments for doing this are very compelling.

Appendix 1: the AHEAD Study Pilot Questionnaire (Hard Copy version)

Please note: the QR code and weblink to the online version of the questionnaire are now disabled. Please contact lead investigator emma.foster@monash.edu should you wish to view the online version of the questionnaire.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

References

G. B. D. Headache collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of migraine and tension-type headache, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the global burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet Neurol. (2018) ;17(11):954–976

Vos T, Lim SS, Abbafati C, Abbas KM, Abbasi M, Abbasifard M et al (2020) Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the global burden of Disease Study 2019. Lancet 396(10258):1204–1222

Britt H, Miller GC, Henderson J, Charles J, Valenti L, Harrison C et al (2012) General practice activity in Australia 2011-12. Sydney

King NJ, Sharpley CF (1990) Headache activity in children and adolescents. J Paediatr Child Health 26(1):50–54

Wilkinson IA, Halliday JA, Henry RL, Hankin RG, Hensley MJ (1994) Headache and asthma. J Paediatr Child Health 30(3):253–256

Mitchell P, Wang JJ, Currie J, Cumming RG, Smith W (1998) Prevalence and vascular associations with migraine in older australians. Aust N Z J Med 28(5):627–632

Australian Bureau of Statistics (2018) National Health Survey: first results, 2017-18. ABS, Canberra

Australian Institute of Health (2016) and Welfare. Australia’s heatlh 2016. Canberra

Tu S, Liew D, Ademi Z, Owen AJ, Zomer E (2020) The Health and Productivity Burden of migraines in Australia. Headache 60(10):2291–2303

Stovner LJ, Al Jumah M, Birbeck GL, Gururaj G, Jensen R, Katsarava Z et al (2014) The methodology of population surveys of headache prevalence, burden and cost: principles and recommendations from the global campaign against Headache. J Headache Pain 15:5

Steiner TJ, Gururaj G, Andree C, Katsarava Z, Ayzenberg I, Yu SY et al (2014) Diagnosis, prevalence estimation and burden measurement in population surveys of headache: presenting the HARDSHIP questionnaire. J Headache Pain 15(1):3

Wei D, Wong LP, Loganathan T, Tang RR, Chang Y, Zhou HN et al (2023) Validation studies on migraine diagnostic tools for use in nonclinical settings: a systematic review. Arq Neuropsiquiatr 81(4):399–412

Andree C, Vaillant M, Barre J, Katsarava Z, Lainez JM, Lair ML et al (2010) Development and validation of the EUROLIGHT questionnaire to evaluate the burden of primary headache disorders in Europe. Cephalalgia 30(9):1082–1100

Steiner TJ, Lipton RB, Lifting The Burden (2018) The global campaign against H. The headache-attributed Lost Time (HALT) indices: measures of burden for clinical management and population-based research. J Headache Pain 19(1):12

Lipton RB, Serrano D, Holland S, Fanning KM, Reed ML, Buse DC (2013) Barriers to the diagnosis and treatment of migraine: effects of sex, income, and headache features. Headache 53(1):81–92

Dodick DW, Loder EW, Manack Adams A, Buse DC, Fanning KM, Reed ML et al (2016) Assessing barriers to Chronic Migraine Consultation, diagnosis, and treatment: results from the chronic migraine epidemiology and outcomes (CaMEO) study. Headache 56(5):821–834

Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation, Results Tool GBD, Seattle (2015) WA: University of Washington; [ http://ghdx.healthdata.org/gbd-results-tool

Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, Elliott V, Fernandez M, O’Neal L et al (2019) The REDCap consortium: building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inf 95:103208

Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG (2009) Research electronic data capture (REDCap)--a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inf 42(2):377–381

Australian Bureau of Statistics 2021 Census All persons QuickStats 2021 [ https://www.abs.gov.au/census/find-census-data/quickstats/2021/AUS

Stovner LJ, Hagen K, Linde M, Steiner TJ (2022) The global prevalence of headache: an update, with analysis of the influences of methodological factors on prevalence estimates. J Headache Pain 23(1):34

Andree C, Stovner LJ, Steiner TJ, Barre J, Katsarava Z, Lainez JM et al (2011) The Eurolight project: the impact of primary headache disorders in Europe. Description of methods. J Headache Pain 12(5):541–549

Australian Longitudinal Study on Women’s Health Recruitment methods 2020 [ https://alswh.org.au/for-data-users/study-design/recruitment-methods/

Smith MG, Witte M, Rocha S, Basner M (2019) Effectiveness of incentives and follow-up on increasing survey response rates and participation in field studies. BMC Med Res Methodol 19(1):230

Australian Government My Health Record, 2023 [ https://www.digitalhealth.gov.au/initiatives-and-programs/my-health-record

Mellish L, Karanges EA, Litchfield MJ, Schaffer AL, Blanch B, Daniels BJ et al (2015) The Australian Pharmaceutical benefits Scheme data collection: a practical guide for researchers. BMC Res Notes 8:634

Straube A, Aicher B, Forderreuther S, Eggert T, Koppel J, Moller S et al (2013) Period prevalence of self-reported headache in the general population in Germany from 1995–2005 and 2009: results from annual nationwide population-based cross-sectional surveys. J Headache Pain 14(1):11

Survey businesswireTNS 75% of Americans Will Never Answer Calls from Unknown Numbers 2022 [ https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20220726005226/en/TNS-Survey-75-of-Americans-Will-Never-Answer-Calls-from-Unknown-Numbers

Lipton RB, Nicholson RA, Reed ML, Araujo AB, Jaffe DH, Faries DE et al (2022) Diagnosis, consultation, treatment, and impact of migraine in the US: results of the OVERCOME (US) study. Headache 62(2):122–140

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to sincerely thank Christine Cormack, Senior Research Coordinator at Prince of Wales Hospital, New South Wales, Australia, for her support throughout this project, and Alison Conquest, Senior Research Coordinator at Monash University, Victoria, Australia, for her assistance with data entry.

Funding

This work was supported by the Brain Foundation, Lundbeck Australia, and Prince of Wales Hospital Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

EF and AZ conceived the study, all authors contributed to the design, ZC conducted the statistical plan and analysis, all authors contributed to the interpretation of data, EF drafted the manuscript, all authors reviewed it critically for important intellectual content, and all authors gave final approval of the version to be published.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was approved by the Alfred Health Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC: 87013), protocol date: 5 October 2022. This study used an ‘opt in’ approach, where it was implied that, by participating in the study, people were consenting to take part.

Competing interests

EF and/or her institution reports grants from Brain Foundation (Australia); LivaNova (USA); Lundbeck (Australia); Monash Partners STAR Clinician Fellowship; Sylvia and Charles Viertel Charitable Foundation; The Royal Australian College of Physicians Fellows Research Establishment Fellowship.ZC was supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia Early Career Fellowship (GNT1156444) and has received grants from the Monash University. His institution has received research funding from UCB Pharma, outside the submitted work.CW is supported by an NHMRC Investigator Grant (APP2008300).ZA reports no disclosures relating to this study.EH reports no disclosures relating to this study. She has served on advisory boards for Sanofi-Genzyme, Novartis, Teva, Eli Lilly, Allergan and Lundbeck, and been involved in clinical trials sponsored by Novartis, Allergan, Lundbeck, Teva, Xalud, Cerecin, and has received payment for educational presentations from Allergan, Teva, Eli Lilly and Novartis. TJS is Director and Trustee of Lifting The Burden, a UK-registered non-governmental organization conducting the Global Campaign against Headache in official relations with the World Health Organization. He is associate editor of The Journal of Headache and Pain. He reports no other disclosures relating to this study.ASZ reports research grants from the Prince of Wales Hospital Foundation and from Lundbeck for the funding of this pilot study.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Foster, E., Chen, Z., Wakefield, C.E. et al. Australian Headache Epidemiology Data (AHEAD): a pilot study to assess sampling and engagement methodology for a nationwide population-based survey. J Headache Pain 25, 71 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-024-01773-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-024-01773-8