Abstract

Background

There have been several calls for estimations of costs and consequences of headache interventions to inform European public-health policies. In a previous paper, in the absence of universally accepted methodology, we developed headache-type-specific analytical models to be applied to implementation of structured headache services in Europe as the health-care solution to headache. Here we apply this methodology and present the findings.

Methods

Data sources were published evidence and expert opinions, including those from an earlier economic evaluation framework using the WHO-CHOICE model. We used three headache-type-specific analytical models, for migraine, tension-type-headache (TTH) and medication-overuse-headache (MOH). We considered three European Region case studies, from Luxembourg, Russia and Spain to include a range of health-care systems, comparing current (suboptimal) care versus target care (structured services implemented, with provider-training and consumer-education). We made annual and 5-year cost estimates from health-care provider and societal perspectives (2020 figures, euros). We expressed effectiveness as healthy life years (HLYs) gained, and cost-effectiveness as incremental cost-effectiveness-ratios (ICERs; cost to be invested/HLY gained). We applied WHO thresholds for cost-effectiveness.

Results

The models demonstrated increased effectiveness, and cost-effectiveness (migraine) or cost saving (TTH, MOH) from the provider perspective over one and 5 years and consistently across the health-care systems and settings. From the societal perspective, we found structured headache services would be economically successful, not only delivering increased effectiveness but also cost saving across headache types and over time. The predicted magnitude of cost saving correlated positively with country wage levels. Lost productivity had a major impact on these estimates, but sensitivity analyses showed the intervention remained cost-effective across all models when we assumed that remedying disability would recover only 20% of lost productivity.

Conclusions

This is the first study to propose a health-care solution for headache, in the form of structured headache services, and evaluate it economically in multiple settings. Despite numerous challenges, we demonstrated that economic evaluation of headache services, in terms of outcomes and costs, is feasible as well as necessary. Furthermore, it is strongly supportive of the proposed intervention, while its framework is general enough to be easily adapted and implemented across Europe.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Many studies, in Europe and elsewhere, have shown that headache disorders are under-diagnosed and under-treated (eg, [1]). Despite the existence of a range of effective therapies [2], these do not reach large numbers of people who might benefit, or do so inefficiently, delivered by health-care providers without the requisite understanding of these disorders [3]. The solution – structured headache services based in primary care and supported by training and education [3, 4], in a model that is readily adaptable across settings and health-care systems – was described in the first paper in this series [5]. In a later paper, in the absence of universally accepted methodology, we developed headache-type-specific analytical models to be applied to economic evaluation of the model, implemented in three countries in the European Region [6]. Here we apply that methodology, and present the findings.

Indirect costs are a key issue in economic evaluation. Because headache disorders are disabling [7,8,9], lost productivity is an important consequence, at demonstrably high cost [10,11,12,13]. Later papers in this series assess the complex relationship between headache-attributed disability and lost productivity, and consider whether, and to what degree, alleviating the former will lead to recovery of the latter [14, 15]. Our evaluation here allows for the possibility that headache-attributed disability explains only part of lost productivity.

Methods

The methods are described in detail in the earlier paper [6]. We modelled cost-effectiveness of structured headache services delivering treatments, with efficacies known from randomised controlled trials, for each of migraine, tension-type headache (TTH) and medication-overuse headache (MOH). We did this in the settings of three European Region countries, Russia, Spain and Luxembourg, with differing health-care systems but for which we had population-based data [16,17,18]. For the two alternatives of current (suboptimal) care and target care (structured services implemented, with provider-training and consumer-education), economic modelling incorporated patient outcomes and cost estimates over two separate timeframes: one and 5 years.

Outcomes were measured in healthy life years (HLYs), and effectiveness as HLYs gained by change from current to target care. We assumed that target care would partially but not entirely close treatment gaps [5]: provider-training within the structured services model would increase coverage and consumer-education would enhance adherence, each, conservatively, by 50% of the gap between current and target care.

Costs included health-care costs (medicines, GP and specialist visits, and examinations) from the provider perspective; additionally, lost productivity (days lost from work) was included in estimates made from the societal perspective. Methodological details are provided elsewhere on the decision-analytical models, on epidemiological data (including disability), estimations of intervention effectiveness, economic outcomes (including use of resources and lost productivity), treatment management plans and selection of interventions for migraine, TTH and MOH within the alternatives under comparison [6].

Economic and effectiveness outcomes were brought together to evaluate cost-effectiveness in terms of costs to be invested per HLY gained (incremental cost-effectiveness ratio [ICER]), with the three health-care systems of Russia, Luxemburg and Spain bringing different systems of health-care service delivery and financing into the model.

Limited evidence supports opportunity-cost–based cost-effectiveness thresholds applicable across diverse countries, including those of interest here. We applied WHO’s thresholds against gross domestic product (GDP) for this purpose: interventions costing < 3*GDP per capita per HLY gained were cost-effective, those costing < 1*GDP per capita per HLY gained were highly cost-effective [19]. Although these lack specificity for any country’s particular contexts, they are the thresholds used by policy makers, who do so in the light of these contexts. Since the overall balance of evidence suggests that WHO’s thresholds may be too high [20], we performed sensitivity analyses to calculate how much we should inflate the costs (or deflate the gains) to meet such thresholds.

The principal analyses were conducted from the health-care provider perspective, with robustness tested in a series of sensitivity analyses inflating health-care costs and deflating HLYs gains while keeping to the same cost-effectiveness thresholds. In a series of secondary analyses, we considered the larger societal perspective. For the baseline societal analysis, we assumed all lost productivity was explained by disease-attributed disability, whereas, in a conservative alternative, we assumed that this disability accounted for only 20% of lost productivity (so that only this proportion might be recovered).

Results

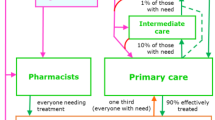

Summaries of the economic and effectiveness outcomes for the treatments of each headache type are presented in Tables 1 (Luxembourg), 2 (Russia) and 3 (Spain). Analytical models according to headache type are reported in Fig. 1.

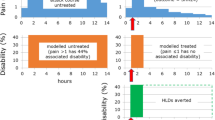

In short-term modelling (1-year time frame) from the health-care provider perspective, the intervention was found to be cost-effective for migraine (Fig. 2) – well below WHO thresholds [19] – and cost saving for TTH and MOH (see Tables 1, 2 and 3). Over 5 years the intervention appeared even more cost-effective for migraine (Fig. 2) and cost-saving for TTH and MOH (the amounts of costs saved are reported in Tables 1, 2 and 3). Sensitivity analyses showed the robustness of these findings (Additional file 1: Appendices 1–3). For example, for Russia and migraine, the intervention was still cost-effective after inflating health-care costs – or deflating effectiveness gains – by factors of 100 (Additional file 1: Appendix 2).

Economic analysis: Incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (euros spent for each HLY gained) at one year and 5 years, from health-provider perspective (migraine). Note: For tension-type headache and medication-overuse headache, the intervention is not only more cost-effective than current care but also cost saving over 1 and 5 years (see Tables 1, 2 and 3)

From the health-care provider perspective, the hypothetical shift to target care would bring gains in HLYs (the longer the time frame the greater the gain). For migraine, resources must be invested to secure these benefits (the longer the time frame, the lower, relatively, the investment). For TTH and MOH, the benefits would be accompanied by cost savings (the longer the time frame the greater the economic gain). Findings were consistent across the health-care systems of the three countries.

From the societal perspective (Additional file 1: Appendices 4–9), the intervention was not only more effective than current care, but also cost saving – for all headache types, across health-care systems and in both 1-year and 5-year time frames. In the conservative scenario, where remedying disability would recover only 20% of lost productivity, the intervention remained cost-effective across all models.

Finally, we considered cost and effectiveness outcomes for 1000 patients with migraine, 1000 with TTH and 1000 with MOH patients in each country setting, allowing comparisons of the impact of introducing target care across country-specific populations (Additional file 1: Appendices 7–9). The greater the country’s wage levels, the greater were the economic savings for society (ie, Luxembourg > Spain > Russia).

Discussion

For the first time, effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of introducing structured headache services have been evaluated. Our results show, across three diverse health-care systems in European Region, that structured headache services based in primary care and supported by consumer-education and provider-training [5] are an effective and economically viable solution to headache disorders and the disability they cause. From the health-care provider perspective, TTH services are not only cost-effective, but also cost-saving (ICERs negative). Although this disorder is associated with much lower estimates of health loss [7,8,9] than migraine or MOH, structured headache services will not discriminate: they are not selective, and must manage all headache types. In practice, people with TTH are least likely to require these services, while the consumer-education component of structured services would be expected to reduce doctor visits for TTH and save health-care resources.

Lost productivity weighs heavily in economic estimates. The savings in work productivity modelled in our study were greater than the investments in health care estimated to meet these savings (a finding predicted long ago by WHO [3]). For TTH, the saving was more evident in Luxembourg, because of its higher wage-levels [10].

Of course, these findings assumed that lost productivity reported as a consequence of headache would, therefore, be recovered commensurately as headache was alleviated. There was reason to doubt this assumption, since many extraneous factors influence the relationship between headache-attributed disability and lost productivity [14, 15]. It is arguable that these factors are much more constant at individual level [15], so that the assumption might hold, but this is untestable. Instead, we relied on sensitivity analyses, in which the intervention remained cost-effective across all models even with the alternative conservative assumption that alleviating headache would recover only 20% of the lost productivity attributed to it.

There have been repeated calls for better modelling of costs and outcomes of headache interventions to inform public-health policies, given the very high prevalence of headache disorders [7, 21,22,23]. There is no widely accepted framework to help European (or other) countries undertake economic evaluation of headache interventions in order to establish which alternative(s) provides the best value for money. Indeed, this topic seems perversely under-researched given the much-increased awareness of the global burden of headache [2, 3, 7,8,9]. To the best of our knowledge, ours is the first study to provide such a framework, and, crucially, it has not confined itself to specific individual treatments but evaluated a health-care delivery package offering a range of treatments. Our work is still incomplete: much remains to be done, particularly in pilot implementations of structured headache services to gather empirical evidence to support our currently hypothetical findings. In the meantime, we have demonstrated that systematic evaluation of headache-type-specific outputs and costs of headache services is feasible (as well as necessary), while work progresses on service quality evaluation [24,25,26,27,28], also of high importance if services are to be implemented.

The principal limitations of this study were those inherent in economic modelling. We were dependent on the type and quality of the data sourced in order to calculate the economic outcomes, the latter being imperfect in Eurolight [29]. Similar limitations applied to the effectiveness outcomes. We made many assumptions in the costing model [6], and could anticipate that our findings would be sensitive to variations in these, but countered this by conducting sensitivity analyses. Although cost-effectiveness thresholds used routinely by WHO (and applied in our analysis) have been criticized for being too high [20], our results appear robust and generally undercut these thresholds.

Conclusions

Even with very conservative assumptions, highly inflating costings (or deflating expected gains), we could conclude that structured headache services would be cost-effective according to WHO thresholds [19] – and this held true for all headache types and across all settings.

The framework of the proposed intervention is general enough to be easily adapted and implemented [5]. Thus, structured headache services offer an efficient, equitable, effective and cost-effective solution to headache, a cause of much population ill health [12, 13, 16] and heavy economic burden [23].

Structured headache services – offering care efficiently and equitably to the widest number of people [5] and, according to our findings here, an economically viable solution to headache as a cause of public ill health – are in accord with WHO’s vision of universal health coverage (UHC) [30]. The concept of UHC is that all people should have access to the health services they need, when and where they need them, without financial hardship. UHC is based on strong, people-centred primary health care, while good health systems are rooted in the communities they serve. Care models like structured headache services that define a clear primary-care role [5] and allow economic evaluation promote the goal of UHC worldwide.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article.

Abbreviations

- GDP:

-

Gross domestic product

- HLY:

-

Healthy Life Year

- ICERs:

-

Incremental cost-effectiveness ratios

- MOH:

-

Medication-overuse headache

- TTH:

-

Tension-type headache

- UHC:

-

Universal health coverage

- WHO:

-

World Health Organization

References

Katsarava Z, Mania M, Lampl C, Herberhold J, Steiner TJ (2018) Poor medical care for people with migraine in Europe - evidence from the Eurolight study. J Headache Pain 19(1):10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-018-0839-1

Steiner TJ, Jensen R, Katsarava Z, Linde M, EA MG, Osipova V, Paemeleire K, Olesen J, Peters M, Martelletti P, on behalf of the European Headache Federation and Lifting The Burden: the Global Campaign against Headache (2019) Aids to management of headache disorders in primary care (2nd edition). J Headache Pain 20:57

World Health Organization, Lifting The Burden (2011) Atlas of headache disorders and resources in the world 2011. WHO, Geneva Available at http://www.who.int/mental_health/management/who_atlas_headache_disorders.pdf?ua=1 (Accessed 13 Dec 2020)

Steiner TJ, Antonaci F, Jensen R, Lainez JMA, Lantéri-Minet M, Valade D, on behalf of the European Headache Federation and Lifting The Burden: the Global Campaign against Headache (2011) Recommendations for headache service organisation and delivery in Europe. J Headache Pain 12(4):419–426. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10194-011-0320-x

Steiner TJ, Jensen R, Katsarava Z, Stovner LJ, Uluduz D, Adarmouch L, Al Jumah M, Al Khathaami AM, Ashina M, Braschinsky M, Broner S, Eliasson JH, Gil-Gouveia R, Gómez-Galván JB, Guðmundsson LS, Kawatu N, Kissani N, Kulkarni GB, Lebedeva ER, Leonardi M, Linde M, Luvsannorov O, Maiga Y, Milanov I, Mitsikostas DD, Musayev T, Olesen J, Osipova V, Paemeleire K, Peres MFP, Quispe G, Rao GN, Risal A, Ruiz de la Torre E, Saylor D, Togha M, Yu SY, Zebenigus M, Zenebe Zewde Y, Zidverc-Trajković J, Tinelli M, on behalf of Lifting The Burden: the Global Campaign against Headache (2021) Structured headache services as the solution to the ill-health burden of headache. 1: rationale and description. J Headache Pain 22 (to be added in proof)

Tinelli M, Leonardi M, Paemeleire K, Mitsikostas D, de la Torre ER, Steiner TJ, on behalf of the European Brain Council Value of Treatment Headache Working Group, the European Headache Federation, the European Federation of Neurological Associations, and Lifting The Burden: the Global Campaign against Headache (2021) Structured headache services as the solution to the ill-health burden of headache. 2: modelling effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of implementation in Europe. Methodol J Headache Pain 22 (to be added in proof)

GBD 2016 Neurology collaborators (2019) Global, regional, and national burden of neurological disorders, 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2016. Lancet Neurol 18:459–480

GBD 2017 Disease and injury incidence and prevalence collaborators (2018) Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2017. Lancet 392:1789–1858

GBD 2019 Viewpoint collaborators (2020) Five insights from the global burden of disease study 2019. Lancet 396:1135–1159

Linde M, Gustavsson A, Stovner LJ, Steiner TJ, Barré J, Katsarava Z, Lainez JM, Lampl C, Lantéri-Minet M, Rastenyte D, Ruiz de la Torre E, Tassorelli C, Andrée C (2012) The cost of headache disorders in Europe: the Eurolight project. Eur J Neurol 19(5):703–711. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-1331.2011.03612.x

Ayzenberg I, Katsarava Z, Sborowski A, Obermann M, Chernysh M, Osipova V, Tabeeva G, Steiner TJ (2015) Headache yesterday in Russia: its prevalence and impact, and their application in estimating the national burden attributable to headache disorders. J Headache Pain 16(1):7. https://doi.org/10.1186/1129-2377-16-7

Stewart WF, Ricci JA, Chee E, Morganstein D, Lipton R (2003) Lost productive time and cost due to common pain conditions in the US workforce. JAMA 290(18):2443–2454. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.290.18.2443

Simić S, Rabi-Žikić T, Villar JR, Calvo-Rolle JL, Simić D, Simić SD (2020) Impact of individual headache types on the work and work efficiency of headache sufferers. Int J Environ Res Public Health 17(18):6918. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17186918

Kothari SF, Jensen RH, Steiner TJ (2021) The relationship between headache-attributed disability and lost productivity. 1. A review of the literature. J Headache Pain 22 (in press)

Thomas H, Kothari SF, Husøy A, Jensen RH, Katsarava Z, Tinelli M, Steiner TJ (2021) The relationship between headache-attributed disability and lost productivity. 2. Empirical evidence from population-based studies in 11 countries. J Headache Pain 22 (in press)

Ayzenberg I, Katsarava Z, Sborowski A, Chernysh M, Osipova V, Tabeeva G, Yakhno N, Steiner TJ (2012) The prevalence of primary headache disorders in Russia: a countrywide survey. Cephalalgia 32(5):373–381. https://doi.org/10.1177/0333102412438977

Ayzenberg I, Katsarava Z, Sborowski A, Chernysh M, Osipova V, Tabeeva G, Steiner TJ (2014) Headache-attributed burden and its impact on productivity and quality of life in Russia: structured healthcare for headache is urgently needed. Eur J Neurol 21(5):758–765. https://doi.org/10.1111/ene.12380

Steiner TJ, Stovner LJ, Katsarava Z, Lainez JM, Lampl C, Lantéri-Minet M, Rastenyte D, Ruiz de la Torre E, Tassorelli C, Barré J, Andrée C (2014) The impact of headache in Europe: principal results of the Eurolight project. J Headache Pain 15(1):31. https://doi.org/10.1186/1129-2377-15-31

World Health Organization (2014) Choosing Interventions that are Cost–Effective (WHO-CHOICE). Project WHO | WHO-CHOICE. WHO Available at https://www.who.int/news-room/feature-stories/detail/new-cost-effectiveness-updates-from-who-choice (Accessed 27 July 2021)

Woods B, Revill P, Sculpher M, Claxton K (2016) Country-level cost-effectiveness thresholds: initial estimates and the need for further research. Value Health 19(8):929–935. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jval.2016.02.017

Stovner LJ, Hagen K, Jensen R, Katsarava Z, Lipton RB, Scher AI, Steiner TJ, Zwart J-A (2007) The global burden of headache: a documentation of headache prevalence and disability worldwide. Cephalalgia 27(3):193–210. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2982.2007.01288.x

Viana M, Khaliq F, Zecca C, Figuerola MDL, Sances G, Di Piero V, Petolicchio B, Alessiani M, Geppetti P, Lupi C, Benemei S, Iannacchero R, Maggioni F, Jurno ME, Odobescu S, Chiriac E, Marfil A, Brighina F, Barrientos Uribe N, Pérez Lago C, Bordini C, Lucchese F, Maffey V, Nappi G, Sandrini G, Tassorelli C (2020) Poor patient awareness and frequent misdiagnosis of migraine: findings from a large transcontinental cohort. Eur J Neurol 27(3):536–541. https://doi.org/10.1111/ene.14098

Steiner TJ, Stovner LJ, Vos T, Jensen R, Katsarava Z (2018) Migraine is first cause of disability in under 50s: will health politicians now take notice? J Headache Pain 19(1):17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-018-0846-2

Peters M, Jenkinson C, Perera S, Loder E, Jensen R, Katsarava Z, Gil Gouveia R, Broner S, Steiner T (2012) Quality in the provision of headache care. 2: defining quality and its indicators. J Headache Pain 13(6):449–457. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10194-012-0465-2

Katsarava Z, Gil Gouveia R, Jensen R, Gaul C, Schramm S, Schoppe A, Steiner TJ (2015) Evaluation of headache service quality indicators: pilot implementation in two specialist-care centres. J Headache Pain 16(1):53. https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-015-0537-1

Schramm S, Uluduz D, Gil Gouveia R, Jensen R, Siva A, Uygunoglu U, Gvantsa G, Mania M, Braschinsky M, Filatova E, Latysheva N, Osipova V, Skorobogatykh K, Azimova J, Straube A, Emre Eren O, Martelletti P, De Angelis V, Negro A, Linde M, Hagen K, Radojicic A, Zidverc-Trajkovic J, Podgorac A, Paemeleire K, De Pue A, Lampl C, Steiner TJ, Katsarava Z (2016) Headache service quality: evaluation of quality indicators in 14 specialist-care centres. J Headache Pain 17(1):111. https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-016-0707-9

Pellesi L, Benemei S, Favoni V, Lupi C, Mampreso E, Negro A, Paolucci M, Steiner TJ, Ulivi M, Cevoli S, Guerzoni S (2017) Quality indicators in headache care: an implementation study in six Italian specialist-care centres. J Headache Pain 18(1):55. https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-017-0762-x

Steiner TJ, Göbel H, Jensen R, Lampl C, Paemeleire K, Linde M, Braschinsky M, Mitsikostas D, Gil-Gouveia R, Katsarava Z, on behalf of the European Headache Federation and Lifting The Burden: the Global Campaign against Headache (2019) Headache service quality: the role of specialized headache centres within structured headache services, and suggested standards and criteria as centres of excellence. J Headache Pain 20:24

Andrée C, Stovner LJ, Steiner TJ, Barre J, Katsarava Z, Lainez JM, Lair M-L, Lanteri-Minet M, Mick G, Rastenyte D, Ruiz de la Torre E, Tassorelli C, Vriezen P, Lampl C (2011) The Eurolight project: the impact of primary headache disorders in Europe. Description of methods J Headache Pain 12(5):541–549. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10194-011-0356-y

World Health Organization. Universal health coverage 2020. Available at: https://www.who.int/health-topics/universal-health-coverage#tab=tab_1 (Accessed 13 Dec 2020)

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors. The work was supported by the European Brain Council as part of the Value of Treatment Project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Consortia

Contributions

All authors supported the conception and design of the project. MT and TS developed the economic evaluation framework and led the data analysis and interpretation. MT produced the first draft and TJS was a major contributor in writing the manuscript. All authors read and commented on the manuscript drafts and approved the final version.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable. Ethics approval was not needed for these economic analyses supported by published data.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Appendix 1.

Baseline vs sensitivity analyses: Luxembourg. Appendix 2. Baseline vs sensitivity analyses: Russia. Appendix 3. Baseline vs sensitivity analyses: Spain. Appendix 4. Luxembourg: economic results of changing from current to target care (population estimates). Appendix 5. Russia: economic results of changing from current to target care (population estimates). Appendix 6. Spain: economic results of changing from current to target care (population estimates). Appendix 7. Differences in outcomes when changing from current to target care (cohorts of 1000 patients per type of headache in Luxembourg). Appendix 8. Differences in outcomes when changing from current to target care (cohorts of 1000 patients per type of headache in Russia). Appendix 9. Differences in outcomes when changing from current to target care (cohorts of 1000 patients per type of headache in Spain).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data.

About this article

Cite this article

Tinelli, M., Leonardi, M., Paemeleire, K. et al. Structured headache services as the solution to the ill-health burden of headache. 3. Modelling effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of implementation in Europe: findings and conclusions. J Headache Pain 22, 90 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-021-01305-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s10194-021-01305-8