Abstract

The demethylation of guaiacyl/syringyl (G/S)-type (G/S = 1/1) and syringyl (S)-type dehydrogenation polymers (DHPs) using iodocyclohexane (ICH) under reflux in DMF was performed to afford demethylated G/S- and S-DHPs in moderate yields. Along with significant structural changes, such as side-chain cleavage and recondensation, as observed using heteronuclear single quantum coherence (HSQC) NMR spectra, the phenolic-OH content of the demethylated DHPs increased, as expected. The tannin-like properties, such as the 1,1-diphenyl-2-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) free radical scavenging ability, iron(III) binding ability, and bovine serum albumin (BSA) adsorption ability, of the demethylated DHPs increased with increasing reaction time. In particular, the BSA adsorption ability was significantly enhanced by demethylation of the G/S- and S-DHPs, and was better than that of G-DHP reported previously. These results indicate that hardwood lignin containing both G and S units is more suitable than softwood lignin containing only G units for functionalization through demethylation into a tannin-like polymer, which has applications as a natural oxidant, metal adsorbent, and protein adsorbent.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Lignin is the second most abundant natural polymer in nature after cellulose. Much attention has been focused on the development of effective utilization of lignin obtained from biorefineries [1]. Tannins are representative plant-derived polyphenols, and have been defined by Swain and Bate-Smith [2] as water-soluble phenolic compounds with a molecular weight range of 500–3000 that precipitate alkaloids and proteins, and exhibit blue colors in the presence of iron (III) chloride. For example, Fig. 1a shows the chemical structure of condensed tannin, also known as wattle tannin, quebracho tannin, persimmon tannin, or bark tannin [3]. Well-known tannin functionalities include protein precipitation, and antioxidant and metal ion adsorption abilities [4]. These unique functionalities are considered part of plant defense mechanisms against insects, fungi, or bacteria, and are primarily due to the abundant free phenolic-OH groups in tannin. Various applications of tannin based on these unique functionalities have been explored, for example, in leather tanning, wood adhesives, wood preservatives, anti-corrosive chemicals for metals, water treatment chemicals, and food additives [5, 6].

Lignin is also a plant-derived polyphenol, and is expected to exhibit tannin-like properties. Indeed, various modified lignins have been reported to exhibit tannin-like properties, such as protein precipitation [7,8,9], and antioxidant [10,11,12] and metal ion adsorption abilities [13, 14]. However, these properties of lignins are typically weaker than those of tannin, because most phenolic-OH groups in lignin are capped as methoxy groups and intermonomeric linkages, such as β-O-4 linkages (Fig. 1b), resulting in a low free phenolic-OH content.

We previously proposed enhancing the potential tannin-like properties of lignin through chemical demethylation using iodocyclohexane (ICH). The results showed that the properties of a guaiacyl dehydrogenation polymer (G-DHP), as a softwood lignin (G-lignin) model, was significantly improved by demethylation. However, the protein precipitation property of G-DHP were not sufficiently improved [15]. In the present study, the demethylation of guaiacyl/syringyl dehydrogenation polymer (G/S-DHP) with G/S = 1/1, as a hardwood lignin (G/S-lignin) model, and syringyl dehydrogenation polymer (S-DHP) with ICH, and their tannin-like properties, were investigated because the higher methoxy contents of G/S- and S-DHPs were favorable for improving these properties.

Experimental

Materials

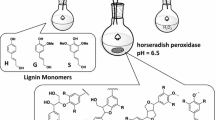

G/S- and S-DHPs were prepared by horseradish peroxidase-catalyzed polymerization of a mixture of coniferyl alcohol and sinapyl alcohol (molar ratio, 1:1), and sinapyl alcohol, respectively, according to the conventional endwise polymerization method, as described previously [15,16,17]. Other reagents were purchased from commercial sources and used without further purification.

Demethylation of G/S- and S-DHPs using ICH

For demethylation of G/S-DHP, ICH (0.970 mL) was added to a solution of G/S-DHP (100 mg) in DMF (2.5 mL), while for demethylation of S-DHP, ICH (1.845 mL) was added to a solution of S-DHP (150 mg) in DMF (3.5 mL). The reaction mixtures were then refluxed for designated reaction periods (5, 60, and 720 min). After cooling to ambient temperature, the reaction mixtures were washed with n-hexane three times, and poured into saturated Na2S2O5 solution [15]. The resulting precipitate was collected by filtration with distilled water, and lyophilized to afford the demethylated DHPs, namely, deMeG/S-DHP and deMeS-DHP from G/S-DHP and S-DHP, respectively.

Characterization of demethylated G/S- and S-DHPs

Folin–Ciocalteu assay and nitroso assay

The DHPs before and after demethylation were subjected to a Folin–Ciocalteu assay for determination of the total free phenolic-OH content [15, 18] and a nitroso assay for qualitative analysis of the catechol residues [15, 19].

Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy

The original and demethylated DHPs were acetylated in acetic anhydride/pyridine at ambient temperature overnight [15]. The acetylated DHPs were dissolved in CDCl3 (~ 30 mg/mL) and subjected to NMR analysis on a Varian FT-NMR (500 MHz) spectrometer (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) operated with Varian VnmrJ 3.2 software. Adiabatic heteronuclear single quantum coherence (HSQC) experiments were performed using the Varian standard implementation (“HSQCAD”) and acquisition parameters were set according to the literature [18, 20]. Data processing was performed using Bruker Topspin 3.1 (Mac) software, and typical matched Gaussian apodization in F2 (LB = −0.5, GB = 0.001), and squared cosine-bell and one level of linear prediction (32 coefficients) in F1, were used. The central chloroform peaks were used for chemical shift calibration (δC 77.0 ppm, δH 7.26 ppm). For volume integration, linear prediction was turned off and no correction factors were used; therefore, the reported data represent volume integrals only.

Gel permeation chromatography (GPC)

The acetylated DHPs were also subjected to GPC analysis for molecular weight determination using a Shimadzu LC-10 system (Shimadzu Co., Kyoto, Japan) equipped with a Shimadzu UV–visible detector (SPD-10Avp) under the following conditions: columns, Shodex K-802, K-802.5, and K-805 columns connected in series (Showa Denko K. K., Tokyo, Japan); column temperature, 40 °C; eluent, CHCl3; flow rate, 1.0 mL/min; sample detection, UV absorbance at 280 nm. Molecular mass calibration was performed using polystyrene standards (Shodex, Showa Denko K. K.).

Tannin-like properties of demethylated G/S- and S-DHPs

The DHPs before and after demethylation were subjected to the following tests according to methods reported in the previous paper [15]. ( +)-Catechin was also tested as a control. All tests were performed twice.

Determination of 2,2-Diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) free radical scavenging ability

2,2-Diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH; 2.5 mg) was dissolved in 90% dioxane/water (v/v, 100 mL). A solution of the demethylated DHP (or original DHP) in 90% dioxane/water (200 μg/mL, 75 μL) was mixed with the DPPH solution (3 mL). The mixture was stirred at ambient temperature for 36 h, and then subjected to UV–vis measurement at 515 nm. The calibration curve was constructed using ( +)-catechin solutions in 90% dioxane/water.

Determination of iron(III) binding ability

The demethylated DHP (or original DHP) (2 mg) was added to a solution of 0.5 mM FeCl3 in 50 mM acetate buffer (pH 5.5, 18 mL). The mixture was sonicated for 3 min in a Branson Ultrasonic Cleaner 3510 J-MT (Branson Ultrasonic CO., Danbury, USA, output: 30 W), stirred at ambient temperature for 18 h, and then centrifuged. The supernatant was treated with 2.5 mM Chrome Azurol S (CAS) aqueous solution (2.6 mL; Nacalai Tesque Inc., Kyoto, Japan), kept at ambient temperature for 10 min, and then subjected to UV–vis measurement at 630 nm. The calibration curve was constructed using a series of FeCl3 solutions in the acetate buffer.

Protein adsorption test

The demethylated DHP (or original DHP) (2 mg) was added to a solution of bovine serum albumin (BSA) in 50 mM acetate buffer (pH 4.5, 8 mL). The mixture was sonicated for 3 min in the ultrasonic cleaner, stirred at ambient temperature for 1 h, and then centrifuged. The supernatant was filtered through cotton wool and treated with Bradford reagent (3 mL). After 10 min, the solution was subjected to UV–vis measurement at 595 nm. The calibration curve was constructed using BSA solutions in the acetate buffer.

Results and discussion

Demethylation of G/S- and S-DHPs using ICH

ICH was the most effective demethylation reagent for G-DHP in our previous investigation [15]. Therefore, G/S-DHP was demethylated using ICH under reflux for 5, 60, and 720 min to give deMeG/S-DHP-5, -60, and -720, respectively, in moderate yields (Table 1). The HSQC NMR spectra of the acetylated original (undemethylated) G/S-DHP (G/S-DHP-Ac) and acetylated deMeG/S-DHP-5, -60, and -720 (deMeG/S-DHP-5-Ac, -60-Ac, and -720-Ac) are shown in Fig. 2 and Additional file 1: Figure S1. The spectrum of G/S-DHP-Ac showed typical lignin aromatic (G and S) and side-chain (I–III, X1) signals. Surprisingly, G-nucleus (G) signals almost disappeared prior to S-nucleus (S) signals in the spectrum of deMeG/S-DHP-5-Ac, along with disappearance of the β-O-4 (I) and coniferyl alcohol-end unit (X1) signals, suggesting preferential cleavage of the G-type methoxy groups and β-O-4 ethers within 5 min of ICH treatment. Furthermore, S-nucleus (S) aromatic signals, and β–5 (II) and β– β (III) intermonomeric linkage signals, disappeared in the spectrum of deMeG/S-DHP-60-Ac. The signals from aromatic methoxy groups (OMe) were clearly considerably decreased in the spectrum of deMeG/S-DHP-60-Ac compared with those in the spectrum of original (undemethylated) G/S-DHP-Ac. All major lignin aromatic and side-chain signals were not detected in the spectrum of deMeG/S-DHP-720-Ac, although trace methoxy signals were still detected. However, new signals at around 120/7.5 (δC/δH) ppm, attributable to catechol and pyrogallol nuclei [15], appeared after 5 min of ICH treatment (deMeG/S-DHP-5-Ac) and increased with an increasing reaction time (deMeG/S-DHP-60-Ac and deMeG/S-DHP-720-Ac). The progress of demethylation and increase in free phenolic-OH content was evaluated by volume integration analysis of the phenolic- and aliphatic-OAc, and aromatic-OMe, signals in the deMeDHPs-Ac. The signal ratio of phenolic-OAc and aliphatic-OAc groups (Ph-OAc/Aliph-OAc) increased with an increasing reaction time, while that of aromatic-OMe and total OAc groups (Ph-OMe/total-OAc) decreased in the HSQC spectra of the deMeG/S-DHPs-Ac (Table 1). In contrast to this observation, the phenolic-OH content of deMeG/S-DHPs, as determined by the Folin–Ciocalteu method [15, 18], increased with an increasing reaction time (Table 1). Furthermore, all deMeG/S-DHPs prepared in this study exhibited positive red coloration after treatment with the nitroso assay reagent, which detects catechol substructures [15, 19] (Table 1, Fig. 3). The average molecular weights (Mw) of the deMeG/S-DHPs-Ac were lower than that of the original G/S-DHP-Ac (Table 1), which might be due to cleavage of the major intermonomeric linkages in the ICH-mediated lignin demethylation [15].

The phenolic-OH content determined for deMeG/S-DHP-720 was 13 mmol/g, which was considerably higher than that (7.8 mmol/g) of deMeG-DHP prepared from G-DHP containing only G aromatic rings via ICH under identical conditions [15]. The presence of S aromatic rings bearing more aromatic methoxy groups clearly contributed to the increased free phenolic-OH content in the resultant demethylated DHP. To further explore this, ICH-mediated demethylation of S-DHP containing only S aromatic rings was performed. We successfully obtained deMeS-DHP-5, -60, and -720 in moderate yields via ICH treatment for 5, 60, and 720 min, respectively. Comparison of the HSQC NMR spectra of acetylated S-DHP (S-DHP-Ac) and deMeS-DHPs (deMeS-DHPs-Ac) demonstrated that structural changes that occurred in deMeS-DHPs-Ac were similar to those observed in deMeG/S-DHPs-Ac, as described earlier (Table 1, Fig. 2, Additional file 1: Figure S2). As expected, the phenolic-OH content of the deMeS-DHPs, as determined by the Folin–Ciocalteu method, greatly increased with an increasing ICH treatment time, reaching 17 mmol/g, which was considerably higher than those of deMeG/S-DHPs (up to 13 mmol/g) (Table 1) and deMeG-DHPs (up to 7.8 mmol/g), [15] and similar to that of the ( +)-catechin standard (17.2 mmol/g) (Table 1). The deMeS-DHPs exhibited positive deep red coloration in the nitroso assay (Table 1, Fig. 3). The molecular weight changes observed in the demethylation of S-DHP were similar to those observed in the demethylation of G/S-DHP, suggesting that cleavage of the major intermonomeric linkages during ICH-mediated lignin demethylation.

Tannin-like properties of demethylated G/S- and S-DHPs

The tannin-like polymer properties, such as antioxidant, metal ion adsorption, and protein adsorption abilities, of deMeG/S-DHPs and deMeS-DHPs were evaluated using DPPH free scavenging ability [10, 11, 21,22,23], iron binding ability [24, 25] and BSA adsorption ability assays [26, 27]. These assays were performed according to our previous report, in which the tannin-like polymer functionalities of demethylated G-DHPs (deMeG-DHPs) were evaluated [15]. ( +)-Catechin, a basic unit of condensed tannin and a well-known natural oxidant [28], was used as a control. The results are summarized in Fig. 4.

The DPPH free radical scavenging ability of deMeG/S-DHPs and deMeS-DHPs increased with an increasing reaction time of ICH-mediated demethylation. A clear correlation between the free radical scavenging ability and phenolic-OH content was observed. The free radical scavenging abilities of deMeG/S-DHP-720 (91%) and deMeS-DHP-720 (90%) were equivalent to that of the ( +)-catechin control (90%). The iron(III) binding ability of deMeG/S-DHPs and deMeS-DHPs also increased with an increasing demethylation reaction time and phenolic-OH content, although the iron(III) binding abilities of deMeS-DHP-60 (81%) and -720 (78%) were comparable to that of the ( +)-catechin control (82%). Furthermore, the buffer solutions of deMeG/S-DHP-720 and deMeS-DHP-720 turned a bluish-dark brown color with the addition of iron(III) chloride, while those of non-demethylated G/S- and S-DHPs were light-yellow (Fig. 5). This coloration observed for the demethylated DHPs was in agreement with the definition of tannin by Swain and Bate-Smith [2], and was most likely driven by the metal-chelating ability of the catechol units introduced into the demethylated DHPs [15, 29]. The BSA adsorption abilities of deMeG/S-DHPs and deMeS-DHPs were likewise significantly enhanced by demethylation. Intriguingly, the demethylated DHPs showed excellent BSA adsorption abilities (up to 88% for deMeS-DHP-720), greatly surpassing that of the catechin control (9%). Condensed tannins reportedly show greater protein-binding affinities with increasing molecular weight as well as phenolic-OH content [30]. Therefore, demethylated lignins with higher molecular weights and higher phenolic-OH contents, namely, those with higher S unit contents in the original lignins, are conceivably more suitable for applications in tannin-like polymer materials, especially in terms of the protein binding ability. Collectively, functionalization through ICH-mediated demethylation (conversion to tannin-like polymers) was found to be more preferable to apply to hardwood lignin (G/S-lignin) than to softwood lignin (G-lignin).

Conclusions

The reactions of G/S-DHP (G/S = 1/1) and S-DHP with ICH were investigated as a basic study of hardwood lignin functionalization through chemical demethylation. The demethylation of G/S- and S-DHPs proceeded efficiently along with significant structural changes, such as cleavage of the side-chain structures and recondensation, as demonstrated by 2D HSQC NMR, chemical structural characterization, and GPC of the resulting demethylated DHPs. The tannin-like properties, namely, DPPH free radical scavenging ability, iron(III) ion binding ability, and BSA adsorption ability, of the demethylated G/S- and S-DHPs considerably increased with an increasing demethylation reaction time, along with an increase in free phenolic-OH content in the polymer. The data indicated that increased S units in the original lignin contribute to a significant increase in free phenolic-OH content in the resulting demethylated lignin, which contributes to further enhancing the tannin-like polymer functionalities. Therefore, hardwood lignins rich in S units are more suitable than softwood lignins containing only G units for conversion into tannin-like polymers with better functionalities via ICH-mediated demethylation. Such lignin-derived tannin-like polymers might have applications as biomass-based functional polymers, such as immobilized enzyme fixed carriers, protein adsorbents, bio-based oxidants for medical and cosmetic products, and heavy metal adsorbents for wastewater treatment.

Availability data and materials

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- BSA:

-

Bovine serum albumin

- DPPH:

-

2,2-Diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl

- ICH:

-

Iodocyclohexane

- G-DHP:

-

Guaiacyl dehydrogenation polymer

- G/S-DHP:

-

Guaiacyl/syringyl dehydrogenation polymer

- S-DHP:

-

Syringyl dehydrogenation polymer

- NMR:

-

Nuclear magnetic resonance

- HSQC:

-

Heteronuclear single quantum coherence

- GPC:

-

Gel permeation chromatography

References

Upton BM, Kasko AM (2016) Strategies for the conversion of lignin to high-value polymeric materials: review and perspective. Chem Rev 116:2275–2306

Swain T, Bate-Smith C (1962) Flavonoid compounds. In: Florkin M, Mason HS (eds) Comparative Biochemistry. Constituent of life–Pat A, vol III. Academic Press, New York

Yazaki Y (2014) Utilization of flavonoids compounds from bark and wood: a review. Nat Prod Commun 10(3):513–520

Santos-Buelga C, Scalbert A (2000) Proanthocyanidins and tannin-like compounds—nature, occurrence, dietary intake and effects on nutrition and health. J Sci Food Agric 80:1094–1117

Pizzi A (2019) Tannins: prospectives and actual industrial applications. Biomolecules 9:344

Das AK, Islam MN, Frauk MO, Ashaduzzaman M, Dungani, (2020) Review on tannins: extraction processes, applications and possibilities. S Afr J Bot 135:58–70

Kawamoto H, Nakatsubo F, Murakami K (1992) Protein-adsorbing capacities of lignin samples. Mokuzai Gakkaishi 38(1):81–84

Zahedifar M, Castro FB, Ørskov ER (2002) Effect of hydrolytic lignin on formation of protein–lignin complexes and protein degradation by rumen microbes. Anim Feed Sci Technol 95(1):83–92

Yoshida T, Lu R, Han S, Hattori K, Katsuta T, Takeda K, Sugimoto K, Funaoka M (2009) Laccase-catalyzed polymerization of lignocatechol and affinity on proteins of resulting polymers. J Polym Sci Part A Polym Chem 47:824–832

Dizhbite T, Telysheva G, Jurkjane V, Viesturs U (2004) Characterization of the radical scavenging activity of lignins—natural antioxidants. Biores Technol 95:309–317

Nsimba RY, West N, Boateng AA (2012) Structure and radical scavenging activity relationships of pyrolytic lignins. J Agric Food Chem 60:12525–12530

Zhang S, Zhang Y, Liu L, Fang G (2015) Antioxidant activity of organosolv lignin degraded using SO42-/ ZrO2 as catalyst. BioResources 10(4):6819–6829

Guillon E, Merdy P, Aplincourt M, Dumonceau J, Vezin H (2001) Structural characterization and iron (III) binding ability of dimeric and polymeric lignin models. J Colloid Interface Sci 239:39–48

Ge Y, Li Z (2018) Application of lignin and its derivatives in adsorption of heavy metal ions in water: a review. ACS Sustain Chem Eng 6:7181–7192

Sawamura K, Tobimatsu Y, Kamitakahara H, Takano T (2017) Lignin functionalization through chemical demethylation: preparation and tannin-like properties of demethylated guaiacyl-type synthetic lignins. ACS Sustain Chem Eng 5:5424–5431

Tobimatsu Y, Takano T, Kamitakahara H, Nakatsubo F (2006) Studies on the dehydrogenative polymerizations of monolignol β-glycosides. Part 2: horseradish peroxidase-catalyzed dehydrogenative polymerization of isoconiferin. Holzforschung 60:513–518

Tobimatsu Y, Takano T, Kamitakahara H, Nakatsubo F (2008) Studies on the dehydrogenative polymerizations of monolignol β-glycosides. Part 3: horseradish peroxidase-catalyzed polymerizations of triandrin and isosyringin. J Wood Chem Technol 28(2):69–83

Bond T J, Analysis and purification of catechins and their transformation products. In: Santos-Buekga C, Williamson G (ed) Methods in polyphenol analysis, Athenaeum Press: Gateshead.

Tobimatsu Y, Chen F, Nakashima J, Escamilla-Treviño LL, Jackson L, Dixon RA, Ralph J (2013) Coexistence but independent biosynthesis of catechyl and guaiacyl/syringyl lignin polymers in seed coats. Plant Cell 25:2587–2600

Tobimatsu Y, Davidson CL, Grabber JH, Ralph J (2011) Fluorescence-tagged monolignols: synthesis, and application to studying in vitro lignification. Biomacromol 12:1752–1761

Diouf P-F, Merlin A, Perrin D (2006) Antioxidant properties of wood extracts and colour stability of woods. Ann For Sci 63:525–534

Makino R, Ohara S, Hashida K (2011) Radical scavenging characteristics of condensed tannins from bark of various tree species compared with quebracho wood tannin. Holzforshung 65:651–657

Chai W-M, Shi Y, Feng H-L, Qiu L, Zhou H-C, Deng Z-W, Yan C-L, Chen Q-X (2012) NMR, HPLC-ESI-MS and MALDI-TOF MS analysis of condensed tannins from Delonix regia (Bojer ex Hook.) Raf. And their bioactivities. J Agric Food Chem 60:5013–5020

Nishida H (1970) A study on the spectrophotometric determination of iron (III) with Chromazurol S. Japan Analyst 19:221–226

Engels C, Gӓnzle MG, Schieber A (2010) Fractionation of gallotannins from mango (Mangifera indica L.) kernels by high-speed counter-current chromatography and determination of their antibacterial activity. J Agric Food Chem 58:775–780

Kawamoto H, Nakatsubo F, Murakami K (1996) Stoichiometric studies of tannin-protein co-precipitation. Phytochemistry 41(5):1427–1431

Naczk M, Oickle D, Pink D, Shahidi F (1996) Protein precipitating capacity of crude canola tannins: effect of pH, tannin, and protein concentrations. J Agric Food Chem 44:2144–2148

Braicu C, Ladomery MR, Chedea VS, Irimie A, Berindan-Neagoe I (2013) The relationship between the structure and biological actions of green tea catechins. Food Chem 141:3282–3289

Perron NR, Brumaghim JL (2009) A review of the antioxidant mechanisms of polyphenol compounds related to iron binding. Cell Biochem Biophys 53:75–100

Huang XD, Liang JB, Tan HY, Yahya R, Long R, Ho YW (2011) Protein-Binding Affinity of Leucaena Condensed Tannins od Differing Molecular Weights. J Agric Food Chem 59:10677–10682

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

TK contributed to all experiments (demethylation of G/S- and S-DHPs and evaluation of their tannin-like properties). YT and HK supported TK’s experiments. TT (corresponding author) designed this study and wrote this paper with YT. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1: Figure S1.

HSQC NMR spectra of acetylated G/S-DHP and acetylated deMeG/S-DHPs (solvent: CDCl3). Figure S2. HSQC NMR spectra of acetylated S-DHP and acetylated deMeS-DHPs (solvent: CDCl3).

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Kobayashi, T., Tobimatsu, Y., Kamitakahara, H. et al. Demethylation and tannin-like properties of guaiacyl/syringyl-type and syringyl-type dehydrogenation polymers using iodocyclohexane. J Wood Sci 68, 51 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1186/s10086-022-02059-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s10086-022-02059-w