Abstract

The crystal plasticity finite element method (CPFEM) is widely used to explore the microscopic mechanical behavior of materials and understand the deformation mechanism at the grain-level. However, few CPFEM simulation studies have been carried out to analyze the nanoindentation deformation mechanism of polycrystalline materials at the microscale level. In this study, a three-dimensional CPFEM-based nanoindentation simulation is performed on an Inconel 718 polycrystalline material to examine the influence of different crystallographic parameters on nanoindentation behavior. A representative volume element model is developed to calibrate the crystal plastic constitutive parameters by comparing the stress-strain data with the experimental results. The indentation force-displacement curves, stress distributions, and pile-up patterns are obtained by CPFEM simulation. The results show that the crystallographic orientation and grain boundary have little influence on the force-displacement curves of the nanoindentation, but significantly influence the local stress distributions and shape of the pile-up patterns. As the difference in crystallographic orientation between grains increases, changes in the pile-up patterns and stress distributions caused by this effect become more significant. In addition, the simulation results reveal that the existence of grain boundaries affects the continuity of the stress distribution. The obstruction on the continuity of stress distribution increases as the grain boundary angle increases. This research demonstrates that the proposed CPFEM model can well describe the microscopic compressive deformation behaviors of Inconel 718 under nanoindentation.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

The traditional method for evaluating the mechanical behavior of materials, which is usually time consuming and expensive, is to conduct a large number of experiments, followed by complex analysis to obtain the results. Furthermore, when assessing the integrity of in-service equipment, such a sampling test method will cause additional damage to the structure. Moreover, it is difficult to obtain sufficient material for testing mechanical properties in sampling restricted situations, such as the heat affected zone of welded joints. Consequently, new evaluation test methods have been developed that replace these large samples with small or even no samples. Nanoindentation is a non-destructive or micro-destructive method used to measure the mechanical behaviors of materials that has attracted wide attention due to its advantages in terms of the small sample required, wide application range, rich types of measurement parameters, and ability to be used for in-service equipment detection [1,2,3,4]. It can be used to obtain abundant mechanical properties, including hardness, modulus, strength, fracture toughness, creep properties, etc., with simple experiments and a small amount of finite element simulations [5,6,7].

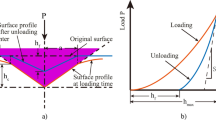

The nanoindentation experiment is a complex deformation process, and the information obtained using only this method is limited. By utilizing the finite element method (FEM), we can explain the indentation deformation process more easily and acquire more information. However, the results obtained by traditional FEM using the elastic-plastic theory are uniform under the assumption of isotropic mechanical behavior (as shown in Figure 1). In addition, this method cannot capture the anisotropic characteristics of polycrystalline materials at the micro-nano level, which is important in nanoindentation. Research has shown that at the microscopic scale, the local mechanical behavior of polycrystalline materials is influenced by crystallographic parameters such as grain boundaries, crystallographic orientation, and grain size to a great extent [8,9,10]. Figure 2 shows the stress-strain curves of a nickel-based single crystal with four different crystallographic orientations (the Euler angles (\(\varphi\), θ, ϕ) of orientations 1 to 4 are (71.3°, 70.2°, 117.7°), (191.3°, 38.4°, 23.8°), (0°, 90°, 315°), and (120.4°, 214.8°, 324.7°), respectively), which indicates that the crystallographic orientations have a significant influence on the mechanical behavior of the material. Therefore, the crystal plasticity (CP) constitutive theory has been extensively used in nanoindentation to obtain more detailed information on the deformation mechanism of polycrystalline materials at the microscale level.

The origin of the crystal plasticity finite element method (CPFEM) can be traced back to Pierce et al. [11], where it was used to explore the mechanical behavior of a single crystal material. Subsequently, CPFEM was successfully applied to the field of polycrystalline materials by Harren et al. [12]. After several decades of development, the microstructure-based CPFEM has been widely used to investigate the microscopic deformation of polycrystals and understand the deformation mechanism at the grain-level more deeply, for example in Refs. [13, 14]. Many studies have also applied CPFEM to nanoindentation simulations. For instance, Liu et al. [15] studied the nanoindentation mechanical response of single crystals of copper with (100), (011), and (111) orientations using a combination of experiments and CPFEM simulations. Results showed that the indentation pile-up patterns, maximum indentation depth, shear stress distribution, and indentation hardness depended on the crystallographic orientation to a great extent. Li et al. [16] carried out a three-dimensional nanoindentation study using CPFEM on an aluminum alloy, and the results confirmed that the deformation of the region below the indenter depended on the crystallographic orientation and grain boundary to a considerable degree. Han et al. [17] used CPFEM simulation to prove that the grain boundary influenced the micromechanical behavior of nanoindentation of a Ti-6Al-4V alloy, verifying that the impact increased as the grain boundary and the indenter became closer to each other.

Nickel-based Inconel 718 superalloy has been extensively applied in aerospace industries because of its outstanding oxidation resistance, superior corrosion and creep resistance, and admirable structural stability at elevated temperature [18, 19]. Despite many previous works that have successfully investigated the micromechanical behavior of Inconel 718 using the nanoindentation testing method [20, 21], to the best of our knowledge, few CPFEM simulation studies have been carried out to analyze the effect of various crystallographic parameters on the indentation behavior of Inconel 718 superalloy.

In this study, a three-dimensional nanoindentation FEM is established and applied by CPFEM to explore the influence of different crystallographic parameters on the indentation behavior of Inconel 718 superalloy. The indentation force-displacement curves, stress-strain distributions, and pile-up patterns are analyzed and compared to verify the impact of the crystallographic parameters.

2 Computational Method

2.1 Crystal Plasticity Constitutive Model

In this work, a crystal plasticity constitutive model is employed to represent the inelastic deformation of a polycrystalline material at the microscale. For the crystallographic model, the total deformation gradient can be multiplicatively decomposed into two parts based on large deformation theory [22], as follows [23]:

where Fe denotes the elastic part caused by lattice stretching and rotation, and Fp denotes the plastic part representing the plastic deformation gradient of the crystal lattice along the slip direction.

For the plastic deformation of the αth slip system, the corresponding inelastic velocity gradient LP depends on the plastic slip ratio \(\dot{{\gamma }^{{\alpha }}}\) [24], which can be defined as:

where mα and nα are unit vectors used to represent the slip direction vector and the normal vector of the slip plane on the αth slip system, respectively. N delegates the gross amount of active slip systems, and the mathematical symbol ⊗ represents a dyadic product.

The crystallographic slip rate of the αth slip system \(\dot{{\gamma }^{\alpha }}\) is expressed as being correlated with the resolved shear stress τα, the back stress Bα, and the slip resistance Sα, following the activation flow criterion [25]:

where \(\dot{{\gamma }_{0}}\), F0, and τ0 are components representing the reference strain rate, total free energy to overcome the lattice resistance, and lattice friction stress at 0 K, respectively; k donates the Boltzmann constant, T is the absolute temperature, and p and q are material parameters associated with the material properties. The mathematical symbol <·> is the MaCauley bracket, which represents the relationship that when x≥0 then < x > = x, and when x<0 then < x > = 0.

The resolved shear stress of the αth slip system, following the works of Li et al. [26, 27], can be written as:

The second Piola-Kirchoff stress, \(\varvec{T}^{*}\), is given by:

where C is the fourth-order stiffness tensor, which is a function of three elastic stiffness constants for FCC crystals, and Ee is the elastic Green tensor [28].

The slip resistance Sα is described according to Ref. [29]:

where S0 is the initial slip resistance, Sβ is the slip resistance on the βth slip system, Ssat is the saturated slip resistance, and hαβ is the hardening matrix, given by:

where hs and δαβ are the hardening constant and Kronecker delta, respectively, and w refers to the latent hardening behavior of the material. The value of w in this work is assumed to be 1 [30].

The above-mentioned CPFEM model is written in a user-defined subroutine (UMAT) and integrated within the ABAQUS standard solver for finite element simulation.

2.2 Parameter Calibration of CPFEM Model

In microscale simulation research, a representative volume element (RVE) model consisting of only a few grains to replace the mechanical behavior of large sized samples is typically used to greatly reduce the simulation time [31, 32]. In this work, a RVE model has been developed using the Voronoi tessellation (VT) method to calibrate the crystal plastic constitutive parameters of Inconel 718 superalloy. The RVE model is composed of 150 grains, which was proven to be enough to represent the mechanical behavior of large sized specimens [33]. All grains in the RVE model are randomly given different crystallographic orientations, as shown in Figure 3. The boundary conditions of the simulated model are as follows: the degrees of freedom in the x-direction of the left boundary are fully constrained but those of the y-direction are not constrained; the upper and top boundaries keep the same displacement in the y-direction by adopting multi-point constraints; and the target displacement load is applied on the right boundary.

The CPFEM results are compared with those of the macro-scale standard experiment [34], and the parameters of CPFEM model are calibrated using a trial-and-error technique. Figure 4 shows the comparison curves between the final stress-strain data obtained by CPFEM and the macro-scale standard experiment, indicating that after parameter calibration, the simulation results by CPFEM agree well with the experimental data. The CPFEM parameters of Inconel 718 are presented in Table 1. It should be noted that once the calibration of CPFEM parameters was successfully completed, the same set of CPFEM parameters was used in all subsequent nanoindentation simulations.

Comparison of stress-strain data of Inconel 718 between experimental [34] and CPFEM simulation results

3 Numerical Simulation Procedure

3.1 Establishment of Indentation Model and Simulation Process

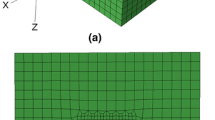

The nanoindentation model established in this study is illustrated in Figure 5. To simplify the finite element simulations, the indenter used in nanoindentation simulation can be assumed to be rigid because the indenter is usually made of hard materials such as diamond whose elastic modulus is much larger than that of the tested material. The diameter of the indenter’s spherical end is 1.5 μm, and the dimensions of the model are 10 μm × 10 μm × 5 μm (x × y × z). The finite element model is meshed with 3D hexahedric linear integration elements (C3D8). Because nanoindentation is a typical contact problem and the main focus area is underneath the indenter, for the purpose of improving the astringency and astringent rate of the simulation, the mesh in the contact area is refined while a lager grid structure is applied to the remaining area. The friction coefficients between the indenter and the tested sample of all simulations in this work are set to be zero, meaning that the contact conditions are assumed to be frictionless. The bottom surface is fixed in three normal directions and the four surrounding surfaces are constrained along the x or y direction for the entire numerical simulation process. The indenter can move freely only along the z direction, and the degrees of freedom in other directions are fully constrained. The displacement control method is adopted in this simulation, and the indenter moves along the z-axis at a fixed displacement rate. The thickness of the sample should be more than ten times the impressed depth to minimize the effect of external factors such as the specimen dimensions and boundaries on the simulation results. The maximum indentation depth of all the simulations performed in this work are set to be 500 nm, which meets the requirements mentioned above. Figure 6 shows the force-displacement curves under three different impressed depths (500 nm, 800 nm, and 1000 nm). It is apparent that the initial unloading stage under the three impressed depths have almost the same slope. Therefore, the plastic zone is reached at an indentation depth of 500 nm, which means the selected indentation depth of 500 nm meets the simulation requirements.

The total simulation process can be divided into 3 steps: (i) Preloading stage: A small displacement load (such as 1 nm) is performed to establish a stable contact relationship between the indenter tip and the impressed specimen to prevent drastic changes in the contact state. (ii) Loading stage: After the establishment of a stable contact relationship, the target displacement load is applied to the FEM. Then, the indenter is moved along the g-axis down to the maximum indentation displacement of 500 nm. (iii) Unloading stage: When the maximum indentation displacement is reached, the indenter is gradually removed from the contact surface at a certain rate. The entire simulation process is carried out in the standard solver of ABAQUS through the user-defined material subroutine.

3.2 Mesh Independency Analysis

The finite element mesh control plays a crucial role in the simulation results. A mesh-sensitivity study of the nanoindentation model is necessary to avoid the mesh effect on nanoindentation simulation analysis and to determine the best mesh scheme based on simulation time and accuracy. Four different mesh sizes were selected for analysis, and the minimum mesh sizes of the model were set to be 0.1, 0.2, 0.3, and 0.4 μm, respectively. From the macroscopic simulation results, a relatively large gap between the indentation force-displacement curves obtained by the coarsest mesh and the finest mesh can be observed, as shown in Figure 7, while the force-displacement curves obtained with mesh sizes values of 0.3 and 0.4 μm coincide quite well. Considering that the simulation time with the finest mesh value of 0.4 μm is over 10 times that with a mesh value of 0.3 μm and that the convergence of the indentation contact analysis will deteriorate when the mesh refinement is excessive, a mesh size value of 0.3 μm can be considered as the best meshing scheme for this simulation work.

4 Results and Discussion

4.1 Crystallographic Orientation Effect

To investigate the influence of crystallographic orientation on the nanoindentation mechanical behavior of Inconel 718, six sets of different crystallographic orientations (Euler angles) are selected and assigned to the same grain in the model (grain 1 in Figure 8(a)), while the crystallographic orientations of the remaining grains remain unchanged, as shown in Table 2. The indentation positions are selected at the center of the indented grain (grain 1) to reduce the impact of grain boundaries on the simulation results.

Figure 9 shows the force-displacement curves under different crystallographic orientation and demonstrates that the maximum variation of the peak load when the indentation depth reaches 500 nm is 3.55%. All six simulations with different crystallographic orientations have similar slopes during the unloading period. This indicates that the influence of crystallographic orientation on the force-displacement curve of nanoindentation is limited. Local deformation occurs when the indenter is applied to the grain, and this deformation is constrained by the indentation depth and surrounding materials. The indentation area shows a complex multi-directional stress state. The loading-unloading process of the indentation reflects the comprehensive mechanical response of the material in different directions. Although different crystallographic mechanical properties are set for each grain in the finite element simulation, the final reflection includes comprehensive material properties in all directions due to the action characteristics of the indentation test. Thus, there are no obvious differences in the force-displacement curves. However, the change of crystallographic orientation has a great influence on the stress distribution and pile-up patterns around the indentation. The stress distributions of different crystallographic orientations at the maximum indentation depth are shown in Figure 10. This demonstrates that the state of stress distribution depends on the crystallographic orientation to a certain degree. The stress is symmetrically distributed, and the axis of symmetry changes as the crystallographic orientation changes.

The evolution of the pile-up patterns in different crystallographic orientations is illustrated in Figure 11. The pile-up patterns are symmetrically distributed in different crystallographic orientations, which is consistent with the results of monocrystalline copper under different crystallographic orientations observed by Wang et al. [35]. Besides, the differences in indentation pile-up patterns are connected to the crystallographic misorientation. The cases OR1 and OR2 have the smallest misorientation, and the pile-up patterns of the two are the most similar, with four protrusions. The cases OR1 and OR4 have the largest misorientation, which leads to the obvious differences between their pile-up patterns. In other words, differences in the pile-up patterns increase as misorientation between the crystal grains increases. The crystallographic orientation dependence of the pile-up patterns is mainly caused by anisotropic crystallographic plastic deformation [17].

The comparison of the maximum Schmid factor of the grain (grain 1 in Figure 8) and the maximum plastic strain along different crystallographic orientations is shown in Figure 12. The Schmid factor is a typical parameter that can be used to describe the influence of crystallographic orientation [36]. A larger Schmid factor results in a greater degree of plastic slip [37]. It can be seen in Figure 12 that the variation tendency of the maximum local plastic strain under the indenter along different crystallographic orientations is consistent with the change of Schmid factor of the indented grain. The grain (grain 1) in case OR4 has the smallest Schmid factor, and its corresponding maximum plastic strain value is also the smallest.

4.2 Influence of Grain Boundary and Grain Boundary Angle

The effect of grain boundary on the indentation behavior at the microscale is studied by changing the indentation position. As shown in Figure 8(b), it is indented at the grain center (center), boundary of two grains (GB2), and trigeminal grain boundary (GB3). Figure 13 shows the force-displacement curves obtained by nanoindentation simulation. It can be clearly seen that the maximum variation of the indentation peak load is only 2.94%, indicating that the existence of the grain boundary has little effect on the force-displacement curve of indentation. However, the grain boundary plays a critical part in changing the pile-up patterns and stress distributions. When the indentation position changes, the stress distribution and pile-up patterns exhibit significant differences, as illustrated in Figure 14.

For the sake of further revealing how the grain boundary affects the indentation behavior, the grains (grain 1 and grain 2) in Figure 8(a) on both sides of the grain boundary (GB2) are given different crystallographic orientations, as indicated in Table 3. Figure 15 shows the indentation force-displacement curves for different grain boundary angles. As shown in the figure, the influence on indentation force-displacement curves is still extremely limited, and the maximum peak load error is only 2.78%. Figure 16 shows the stress distribution at different grain boundary angles. This means that the resistance effect of grain boundaries on the continuity of the stress distribution becomes greater as the grain boundary angle increases (from case OM4 to case OM1).

With respect to the pile-up patterns, as shown in Figure 17, changes in the shape of the pile-up patterns are more obvious with an upward trend in grain boundary angle. The grain boundary angles of case OM3 and OM4 are low angle (13.2° and 2.2°, respectively), and the stress distribution and pile-up patterns of the two are almost the same as those of case OR1. On the contrary, the grain boundary angles of case OM1 and OM2 are large angle (53.6° and 38.2°, respectively), and the stress distribution at the grain boundary is obviously discontinuous with a significant change in the shape of the pile-up patterns.

5 Conclusions

A series of three dimensional nanoindentation finite element simulations that incorporate crystal plasticity theory have been successfully conducted to explore the influence of crystallographic orientation and grain boundaries on the indentation behavior of a polycrystalline Inconel 718 superalloy. The main conclusions of this work are as follows:

-

(1)

These simulation results suggest that differences in crystallographic orientation and the existence of grain boundaries have no significant effect on the indentation force-displacement curves. The maximum variation of peak load caused by different crystallographic orientations is only 3.55%, and the variations caused by different grain boundaries and grain boundary angles are only 2.94% and 2.78%, respectively. Furthermore, the unloading slopes of these simulations under different conditions are all similar.

-

(2)

The stress distribution under indentation area and pile-up patterns of Inconel 718 have a high dependence on crystallographic orientation. When the crystallographic orientation changes, both the stress distribution and the shape of the pile-up patterns will change, and the changes will be larger as the misorientations between grains increase.

-

(3)

The existence of grain boundaries affects the stress distribution and pile-up patterns significantly, and resistance to stress continuity becomes more obvious with an upward trend in grain boundary angle.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

References

M VanLandingham. Review of instrumented indentation. Journal of Research of the National Institute of Standards and Technology, 2003, 108(4): 249–265.

J Li. Impression creep and other localized tests. Materials Science and Engineering: A, 2002, 322: 23–42.

Z Qu, K Wei, Q He, et al. High temperature fracture toughness and residual stress in thermal barrier coatings evaluated by an in–situ indentation method. Ceramics International, 2018, 44(7): 7926–7929.

J Menčík. Determination of mechanical properties by instrumented indentation. Meccanica, 2007, 42(1): 19–29.

W Oliver, G Pharr. An improved technique for determining hardness and elastic modulus using load and displacement sensing indentation experiments. Jmaterres, 1992, 7: 1564–1583.

Y Li, Y Liu, R Wang. Evaluation of the elastic modulus of concrete based on indentation test and multi-scale homogenization method. Journal of Building Engineering, 2021, 43: 102758.

J I Jang. Estimation of residual stress by instrumented indentation: A review. Journal of Ceramic Processing Research, 2009, 10(3): 391–400.

L P Evers, W A M Brekelmans, M G D Geersb. Scale dependent crystal plasticity framework with dislocation density and grain boundary effects. International Journal of Solids and Structures, 2004, 41(18–19): 5209–5230.

S Pathak, J Michler, K Wasmer. Studying grain boundary regions in polycrystalline materials using spherical nano–indentation and orientation imaging microscopy. Journal of Materials Science, 2012, 47(2): 815–823.

T Chen, L Tan, Z Lu, et al. The effect of grain orientation on nanoindentation behavior of model austenitic alloy Fe-20Cr-25Ni. Acta Materialia, 2007, 138: 83–91.

D Peirce, R J Asaro. A Needleman. An analysis of nonuniform and localized deformation in ductile single crystals. Acta Metallurgica, 1982, 30(6): 1087–1119.

S V Harren, H E Dève, R J Asaro. Shear band formation in plane strain compression. Acta Metallurgica, 1988, 36(9): 2435–2480.

F Roters, P Eisenlohr, L Hantcherli, et al. Overview of constitutive laws, kinematics, homogenization and multiscale methods in crystal plasticity finite–element modeling: Theory, experiments, applications. Acta Materialia, 2010, 58(4): 1152–1211.

J L Chaboche. A review of some plasticity and viscoelasticity constitutive theories. International Journal of Plasticity, 2008, 24(10): 1642–1693.

Y Liu, S Varghese, J Ma, et al. Orientation effects in nanoindentation of single crystal copper. International Journal of Plasticity, 2008, 24(11): 1990–2015.

L Li, L Shen, P Gwénaëlle, et al. Three–dimensional crystal plasticity finite element simulation of nanoindentation on aluminum alloy 2024. Materials Science and Engineering: A, 2013, 579: 41–49.

F B Han, B Tang, H C Kou, et al. Experiments and crystal plasticity finite element simulations of nanoindentation on Ti–6Al–4V alloy. Materials Science and Engineering: A, 2015, 625: 28–35.

D Ulutan, T Ozel. Machining induced surface integrity in titanium and nickel alloys: A review. International Journal of Machine Tools and Manufacture, 2011, 51(3): 250–280.

W Hui, Y B Hu, F D Ning, et al. Ultrasonic vibration–assisted laser engineered net shaping of Inconel 718 parts: Effects of ultrasonic frequency on microstructural and mechanical properties. Journal of Materials Processing Technology, 2020, 276: 116395–116395.

H Wang, A Dhiman, H E Ostergaard, et al. Nanoindentation based properties of Inconel 718 at elevated temperatures: A comparison of conventional versus additively manufactured samples. International Journal of Plasticity, 2019, 120: 380–394.

G Z Voyiadjis, R A Znemah, P Wood, et al. Effect of element wall thickness on the homogeneity and isotropy of hardness in SLM IN718 using nanoindentation. Mechanics Research Communications, 2020, 114: 103568.

F Dunne, N Petrinic. Introduction to computational plasticity. New York: Oxford University Press, 2005.

R J Asaro. Micromechanics of crystals and polycrystals. Advances in Applied Mechanics, 1983, 23: 1–115.

R J Asaro, J R Rice. Strain localization in ductile single crystals. Journal of the Mechanics and Physics of Solids, 1977, 25: 309–338.

E P Busso, F A Mcclintock. A dislocation mechanics–based crystallographic model of a B2–type intermetallic alloy. Acta Materialia, 2014, 80: 445–456.

D F Li, B J Golden, N P Odowd. Multiscale modelling of mechanical response in a martensitic steel: A micromechanical and length–scale–dependent framework for precipitate hardening. Acta Materialia, 2014, 80: 445–456.

D F Li, N P O'Dowd. On the evolution of lattice deformation in austenitic stainless steels – The role of work hardening at finite strains. Journal of the Mechanics and Physics of Solids, 2011, 59: 2421–2441.

D F Li, N P O'Dowd, C M Davies, et al. Microscale prediction of deformation in an austenitic stainless steel under uniaxial loading. European Journal of Mechanics–A/solids, 2011, 30: 748–760.

D F Li, C M Davies, S Y Zhang, et al. The effect of prior deformation on subsequent microplasticity and damage evolution in an austenitic stainless steel at elevated temperature. Acta materialia, 2013, 61: 3575–3584.

F Sun, E D Meade, N P O'Dowd. Strain gradient crystal plasticity modelling of size effects in a hierarchical martensitic steel using the Voronoi tessellation method. International Journal of Plasticity, 2019, 119: 215–229.

J G Cailletaud. Intergranular and intragranular behavior of polycrystalline aggregates. Part 1: F.E. model. International Journal of Plasticity, 2001, 17(4): 513–536.

J Alcalá, O Casals, J Očenášek. Micromechanics of pyramidal indentation in fcc metals: Single crystal plasticity finite element analysis. Journal of the Mechanics & Physics of Solids, 2010, 56(11): 3277–3303.

G J Yuan, X C Zhang, B Chen, et al. Low–cycle fatigue life prediction of a polycrystalline nickel–base superalloy using crystal plasticity modelling approach. Journal of Materials Science & Technology, 2020, 38: 28–38.

S Kim, H Choi, J Lee, et al. Room and elevated temperature fatigue crack propagation behavior of Inconel 718 alloy fabricated by laser powder bed fusion. International Journal of Fatigue, 2020, 140: 105802.

Y Wang, D Raabe, C Klüber, et al. Orientation dependence of nanoindentation pile–up patterns and of nanoindentation microtextures in copper single crystals. Acta Materialia, 2004, 52(8): 2229–2238.

F R N Nabarro. Extended dislocations and the schmid law of resolved shear stress. Philosophical Magazine, 1966, 14(130): 861–866.

W Zhang, Y Gao, Y Xia, et al. Indentation Schmid factor and incipient plasticity by nanoindentation pop–in tests in hexagonal close–packed single crystals. Acta Materialia, 2017, 134: 53–65.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Funding

Supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 52130511, 52075174).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

JT and ST were in charge of the whole trial; WZ wrote the manuscript; GY and SC assisted with sampling and simulation analyses. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ Information

Wenbo Zhu, born in 1993, is currently a PhD candidate at MOE Key Laboratory of Pressure Systems and Safety, East China University of Science and Technology, China. His research interest is nanomechanics.

Guangjian Yuan, born in 1991, is currently a PhD candidate at MOE Key Laboratory of Pressure Systems and Safety, East China University of Science and Technology, China.

Jianping Tan, born in 1986, is currently an associate professor at MOE Key Laboratory of Pressure Systems and Safety, East China University of Science and Technology, China.

Shuai Chang, born in 1995, is currently a PhD candidate at MOE Key Laboratory of Pressure Systems and Safety, East China University of Science and Technology, China.

Shantung Tu, born in 1961, is currently a professor at MOE Key Laboratory of Pressure Systems and Safety, East China University of Science and Technology, China.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhu, W., Yuan, G., Tan, J. et al. The Influence of Crystallographic Orientation and Grain Boundary on Nanoindentation Behavior of Inconel 718 Superalloy Based on Crystal Plasticity Theory. Chin. J. Mech. Eng. 36, 95 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1186/s10033-023-00921-6

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s10033-023-00921-6