Abstract

Background

ICU patients frequently undergo chest radiographs (CXRs). The diagnostic and therapeutic efficacy of routine CXRs are now known to be low, but the discussion regarding specific indications for CXRs in critically ill patients and the safety of abandoning routine CXRs is still ongoing. We performed a survey of Dutch intensivists on the current practice of chest radiography in their departments.

Methods

Web-based questionnaires, containing questions regarding ICU characteristics, ICU patients, daily CXR strategies, indications for routine CXRs and the practice of radiologic evaluation, were sent to the medical directors of all adult ICUs in the Netherlands. CXR strategies were compared between all academic and non-academic hospitals and between ICUs of different sizes. A comparison was made between the survey results obtained in 2006 and 2013.

Results

Of the 83 ICUs that were contacted, 69 (83%) responded to the survey. Only 7% of responding ICUs were currently performing daily routine CXRs for all patients, and 61% of the responding ICUs were said never to perform CXRs on a routine basis. A daily meeting with a radiologist is an established practice in 72% of the responding ICUs and is judged to be important or even essential by those ICUs. The therapeutic efficacy of routine CXRs was assumed by intensivists to be lower than 10% or to be between 10 and 20%. The efficacy of ‘on-demand’ CXRs was assumed to be between 10 and 60%. There is a consensus between intensivists to perform a routine CXR after endotracheal intubation, chest tube placement or central venous catheterization.

Conclusion

The strategy of daily routine CXRs for critically ill and mechanically ventilated patients has turned from being a common practice in 2006 to a rare current practice. Other routine strategies and an ‘on-demand only’ strategy have become more popular. Intensivists still assume the value of CXRs to be higher than the efficacy that is reported in the literature.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

ICU patients frequently undergo chest radiographs (CXRs) on a routine basis, after a change in their clinical situation or directly after surgery. Several investigators have studied the clinical value of routine CXRs following central venous catheterization, endotracheal intubation, cardiac surgery, pulmonary surgery or chest tube placement and removal[1–18]. Other investigators have studied the value of daily routine CXRs in a mixed ICU population or in mechanically ventilated patients only[19–28]. The diagnostic and therapeutic efficacy of these routine radiographs is now known to be low[1–3, 6–10, 12–15, 17, 19, 20, 22–25, 28]. Studies that compared a routine CXR strategy with an ‘on-demand’ CXR strategy did not show any difference in outcome measures[29–34].

Despite these results, in 2006, Graat et al. showed that in a majority of ICUs in The Netherlands, a daily routine CXR strategy was still common practice[35]. Intensivists at that time assumed a higher value of daily CXRs than had been reported in the literature. Although a more restrictive CXR strategy seems safe, Ganapathy et al. stated in a more recent meta-analysis that study populations were small and the number of missed findings had not been sufficiently evaluated[33]. Meanwhile, the discussion regarding specific indications for CXRs in critically ill patients and the safety of abandoning routine CXRs is still ongoing. We performed a new survey among Dutch intensivists on their current chest radiography practice in order to study the influence of time and knowledge in relation to any changes in that practice.

Methods

For our study, we selected all Dutch academic hospitals (related to a university medical school) and non-academic hospitals with an independent adult ICU department. A web-based questionnaire (Additional file1), deployed using the website http://www.thesistools.com, was sent to the medical staff of these ICUs by the end of April 2013. A reminder was sent after two weeks, four weeks and six weeks after the questionnaire was originally sent. All hospitals received one questionnaire, as it is currently common in our country to have one adult ICU center with a combined medical staff and a mixed patient population. For data analysis, we included all questionnaires that were answered within eight weeks from the start of the study, with a response of more than 80%. The questionnaire we deployed was based on the questionnaire used previously in 2006[35]. After confirming a specific hospital’s response, this response was made anonymously. To prevent duplicated data, additional responses from the same hospital were not included.

The survey contained questions regarding hospital and ICU characteristics, type of ICU patients, CXR strategies, indications for routine CXRs and the practice of radiologic evaluation. Regarding ICU size, only beds with the possibility of mechanical ventilation were taken into account. We asked the intensivists to judge the clinical value (therapeutic efficacy) of routine and ‘on-demand’ CXRs and to judge the value of an established radiologic evaluation with a radiologist. We finally asked them to state some indications for routine CXRs.

CXR strategies were compared between all hospitals, between academic and non-academic hospitals and between ICUs of different sizes. A comparison was made between the survey results from 2006 and 2013. Therapeutic efficacy was defined as the percent of CXR findings that resulted in a subsequent change in patient management.

Data analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 21.0 (IBM,Armonk, NY, USA). All variables were expressed as counts (%). Differences in CXR strategies between 2006 and 2013 were examined using Fisher’s exact test.

Results

A total of 83 hospitals with an adult ICU were selected for this study, and 69 hospitals (83%) responded to the web-survey. The non-responders were one academic hospital and thirteen non-academic hospitals of limited size. The characteristics of the responding ICU departments are shown in Table 1. Only 10% of the responders were academic hospitals, while 90% of the institutions were non-academic. Most ICUs (58%) had between five and fifteen beds with the option of mechanical ventilation available, and 29% of ICUs had more than fifteen beds with the option of mechanical ventilation available. The most frequent number of fulltime intensivists available was one to five (46%) or five to ten (36%). Cardiac surgery patients were admitted to 29% of the responding ICUs, and neurosurgical patients were admitted to 23% of the responding ICUs.

Of all hospitals, 39% practiced some kind of routine CXR strategy, but only 7% of ICUs obtained daily routine CXRs for all patients (Table 2). Some other ICUs only performed daily routine CXRs for mechanically ventilated patients (6%), patients in the first days of ICU admission (4%), all patients on certain fixed days of the week (3%) or for cardiothoracic surgery patients only (6%). Most ICU departments (61%) state that they never perform daily CXRs on a routine basis. A distinctive group seems to be the academic ICUs and largest non-academic ICUs, because 86% of the academic ICUs and 75% of the ICUs with > 15 beds practice some kind of routine chest radiography strategy

Table 3 presents a comparison of the survey results from 2006 and the results of the current study. The number of ICUs that used some kind of routine CXR strategy decreased from 63 to 39% from 2006 to 2013 (P = 0.018). There was a decrease in the use of a daily routine CXR strategy for all ICU patients although this decrease was not significant (P = 0.324). However, there was an important decrease in the use of a routine CXR strategy for mechanically ventilated patients (P < 0.001). The frequency of other routine strategies and, in particular, of an ‘on-demand only’ strategy increased from 2006 to 2013 (P = 0.095 and P = 0.018). There were no significant differences in the performance of routine CXRs after chest tube placement, endotracheal intubation, central venous catheterization, cardiopulmonary resuscitation or tracheostomy.

The practices of radiologic evaluation with a radiologist are shown in Table 4. The majority of ICUs had a daily established meeting with a radiologist, and this daily meeting also included weekend days for 28% of ICUs and were on weekdays only for 44% of ICUs. Only 12% of the responding ICU departments never evaluate their CXRs in a specially arranged meeting. A daily radiological conference was considered essential by 46% of the ICUs and good for cooperation between medical staff by 74% of the ICUs. The training purposes of a daily radiologic conference were considered important by only 19% of the ICUs.

Table 5 shows the responding intensivists’ assumed therapeutic efficacy values for CXRs performed routinely and CXRs performed on a special indication only (‘on-demand’). The efficacy of routine CXRs was generally assumed to be lower than 10% or to be between 10 and 20%. The efficacy for ‘on-demand’ CXRs was obviously assumed to be higher, somewhere between 10 and 60%.

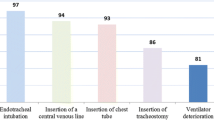

There seems to be a consensus for the indication of a routine CXR after chest tube placement and central venous catheterization (Table 6). Other frequently suggested indications for CXRs are the diagnostic workups for the presence of a pneumothorax, pneumonia or adult respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS).

Discussion

Our results show that a strategy of daily routine CXRs is performed for all patients in only 7% of ICUs and for all mechanically ventilated patients in only 6% of ICUs, while 61% of the ICUs never perform CXRs on a routine basis. A daily meeting with a radiologist is an established practice in the majority of ICUs and is judged to be important or even essential. Our results are in line with the results of Lakhal et al. who did an observational day study in French ICUs in 2010[36]. In their study population, a daily routine CXR strategy was also practiced in 7% of ICUs, while 63% of ICUs never performed routine CXRs. Compared to the results of Graat et al. in 2006, there has been an obvious change in chest radiography strategies in Dutch ICUs. Then, the majority of ICUs practiced a daily routine CXR strategy[35]. An ‘on-demand only’ strategy and other more liberal routine strategies have become more common in recent years.

The indications for routine CXRs suggested by the responders in our survey are, in general, comparable to the indications suggested in the surveys performed by Graat et al. and Hejblum et al.[35, 36]. There is still consensus between intensivists regarding the importance of obtaining a CXR after endotracheal intubation, chest tube placement and central venous catheterization and for diagnostic workups for pneumonia, ARDS or pneumothorax. However, the indications for a routine CXR after intubation and central venous catheterization are not supported by the literature[1–3, 6]. There is no consensus that a routine CXR should be performed for all mechanically ventilated patients[35, 37].

Although our results, and the reduction in routine CXR strategies, suggest that intensivists seem to be aware of the limited clinical value of routine CXRs, they still assume this value to be higher than the efficacy that is reported in the literature[35]. This is also true for the clinical value of ‘on-demand’ CXRs. In recent literature, the reported diagnostic efficacy for CXR small findings is between 30 and 65%, while the diagnostic efficacy for important findings and the therapeutic efficacy of CXRs are reported to be between 2 and 7%[22–24, 28]. Intensivists may assume a higher clinical value of CXRs due to the value of negative CXR findings, which has not been previously studied. The ability of CXR findings to exclude complications, certain clinical situations or the need for an intervention, probably has a clinical impact that is hard to study.

During the last decade, multiple studies have shown that an ‘on-demand’ CXR strategy increases the diagnostic and therapeutic efficacy of CXRs in critically ill patients while subsequently reducing the number of CXRs and subsequent costs significantly. No difference in mortality, length of mechanical ventilation or length of ICU or hospital stay was found[29–34]. Kroner et al. found no change in the number of computed tomography (CT) or ultrasound studies performed by the department of radiology for ICUs that use an ‘on-demand’ CXR strategy[34]. To our knowledge there are no studies regarding the impact of an ‘on-demand’ CXR strategy on the number of ultrasound studies performed by intensivists or vice versa. A routine ultrasound examination of the pleura and pericardium performed by ICU physicians after cardiac surgery or before ICU discharge might further reduce the use routine CXR strategies.

However, completely abandoning routine CXRs for ICU patients is still under debate because the currently available studies did not evaluate the effect of missed findings, had low patient numbers and did not rigorously assess possible harm[33]. More prospective studies need to be performed on the topic of missed findings, the clinical value of negative findings and the indications for CXRs in an ‘on-demand only’ strategy, before a definitive conclusion can be drawn.

Conclusions

The strategy of daily routine CXRs for critically ill and mechanically ventilated patients has turned from being a common practice in 2006 to a rare current practice. Other routine strategies and an ‘on-demand only’ strategy have become more popular. Intensivists still assume that the value of CXRs is higher than the efficacy reported in the literature.

Abbreviations

- ARDS:

-

Adult Respiratory Distress Syndrome

- CPR:

-

Cardiopulmonary resuscitation

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- CVL:

-

Central venous line

- CXR:

-

Chest radiograph

- CXRs:

-

Chest radiographs

- IABP:

-

Intra-aortic balloon pump

- ICU:

-

Iintensive care unit.

References

Lessnau KD: Is chest radiography necessary after uncomplicated insertion of a triple-lumen catheter in the right internal jugular vein, using the anterior approach? Chest 2005,127(1):220–223. 10.1378/chest.127.1.220

Lucey B, Varghese JC, Haslam P, Lee MJ: Routine chest radiographs after central line insertion: mandatory postprocedural evaluation or unnecessary waste of resources? CardiovascInterventRadiol 1999,22(5):381–384.

Sanabria A, Henao C, Bonilla R, Castrillón C, Cruz H, Ramírez W, Navarro P, González M, Díaz A: Routine chest roentgenogram after central venous catheter insertion is not always necessary. Am J Surg 2003,186(1):35–39. 10.1016/S0002-9610(03)00122-3

Abood GJ, Davis KA, Esposito TJ, Luchette FA, Gamelli RL: Comparison of routine chest radiograph versus clinician judgment to determine adequate central line placement in critically ill patients. J Trauma 2007,63(1):50–56. 10.1097/TA.0b013e31806bf1a3

Brunel W, Coleman DL, Schwartz DE, Peper E, Cohen NH: Assessment of routine chest roentgenograms and the physical examination to confirm endotracheal tube position. Chest 1989,96(5):1043–1045. 10.1378/chest.96.5.1043

Lotano R, Gerber D, Aseron C, Santarelli R, Pratter M: Utility of postintubation chest radiographs in the intensive care unit. Crit Care 2000,4(1):50–53. 10.1186/cc650

Hornick PI, Harris P, Cousins C, Taylor KM, Keogh BE: Assessment of the value of the immediate postoperative chest radiograph after cardiac operation. Ann ThoracSurg 1995,59(5):1150–1153. Discussion 1153–4 10.1016/0003-4975(95)00087-2

Karthik S, O'Regan DJ: An audit of follow-up chest radiography after coronary artery bypass graft. ClinRadiol 2006,61(7):616–618.

Rao PS, Abid Q, Khan KJ, Natarajan KM, Morritt GN, Wallis J, Kendall SW: Evaluation of routine postoperative chest X-rays in the management of the cardiac surgical patient. Eur J CardiothoracSurg 1997,12(5):724–729. 10.1016/S1010-7940(97)00132-2

Tolsma M, Kröner A, van den Hombergh CL, Rosseel PM, Rijpstra TA, Dijkstra HA, Bentala M, Schultz MJ, van der Meer NJ: The clinical value of routine chest radiographs in the first 24 hours after cardiac surgery. AnesthAnalg 2011,112(1):139–142.

Mets O, Spronk PE, Binnekade J, Stoker J, de Mol BA, Schultz MJ: Elimination of daily routine chest radiographs does not change on-demand radiography practice in post-cardiothoracic surgery patients. J ThoracCardiovascSurg 2007,134(1):139–144.

Graham RJ, Meziane MA, Rice TW, Agasthian T, Christie N, Gaebelein K, Obuchowski NA, Korevaar JC, Spronk PE, Stoker J, Vroom MB, Schultz MJ: Postoperative portable chest radiographs: optimum use in thoracic surgery. J ThoracCardiovascSurg 1998,115(1):45–50. Discussion 50–2.

Whitehouse MR, Patel A, Morgan JA: The necessity of routine post-thoracostomy tube chest radiographs in post-operative thoracic surgery patients. Surgeon 2009,7(2):79–81. 10.1016/S1479-666X(09)80020-6

Eisenberg RL, Khabbaz KR: Are chest radiographs routinely indicated after chest tube removal following cardiac surgery? AJR Am J Roentgenol 2011,197(1):122–124. 10.2214/AJR.10.5856

Khan T, Chawla G, Daniel R, Swamy M, Dimitri WR: Is routine chest X-ray following mediastinal drain removal after cardiac surgery useful? Eur J CardiothoracSurg 2008,34(3):542–544. 10.1016/j.ejcts.2008.05.002

McCormick JT, O'Mara MS, Papasavas PK, Caushaj PF: The use of routine chest X-ray films after chest tube removal in postoperative cardiac patients. Ann ThoracSurg 2002,74(6):2161–2164. 10.1016/S0003-4975(02)03982-6

Palesty JA, McKelvey AA, Dudrick SJ: The efficacy of X-rays after chest tube removal. Am J Surg 2000,179(1):13–16. 10.1016/S0002-9610(99)00260-3

Sepehripour AH, Farid S, Shah R: Is routine chest radiography indicated following chest drain removal after cardiothoracic surgery? Interact CardiovascThoracSurg 2012,14(6):834–838.

Silverstein DS, Livingston DH, Elcavage J, Kovar L, Kelly KM: The utility of routine daily chest radiography in the surgical intensive care unit. J Trauma 1993,35(4):643–646. 10.1097/00005373-199310000-00022

Fong Y, Whalen GF, Hariri RJ, Barie PS: Utility of routine chest radiographs in the surgical intensive care unit: a prospective study. Arch Surg. 1995,130(7):764–768. 10.1001/archsurg.1995.01430070086017

Brainsky A, Fletcher RH, Glick HA, Lanken PN, Williams SV, Kundel HL: Routine portable chest radiographs in the medical intensive care unit: effects and costs. Crit Care Med 1997,25(5):801–805. 10.1097/00003246-199705000-00015

Graat ME, Choi G, Wolthuis EK, Korevaar JC, Spronk PE, Stoker J, Vroom MB, Schultz MJ: The clinical value of daily routine chest radiographs in a mixed medical-surgical intensive care unit is low. Crit Care 2006,10(1):R11.

Graat ME, Kroner A, Spronk PE, Korevaar JC, Stoker J, Vroom MB, Schultz MJ: Elimination of daily routine chest radiographs in a mixed medical-surgical intensive care unit. Intensive Care Med 2007,33(4):639–644. 10.1007/s00134-007-0542-1

Hendrikse KA, Gratama JW, Hove W, Rommes JH, Schultz MJ, Spronk PE: Low value of routine chest radiographs in a mixed medical-surgical ICU. Chest 2007,132(3):823–828. 10.1378/chest.07-1162

Kager LM, Kröner A, Binnekade JM, Gratama JW, Spronk PE, Stoker J, Vroom MB, Schultz MJ: Review of a large clinical series: the value of routinely obtained chest radiographs on admission to a mixed medical–surgical intensive care unit. J Intensive Care Med 2010,25(4):227–232. 10.1177/0885066610366925

Hall JB, White SR, Karrison T: Efficacy of daily routine chest radiographs in intubated, mechanically ventilated patients. Crit Care Med 1991,19(5):689–693. 10.1097/00003246-199105000-00015

Bhagwanjee S, Muckart DJ: Routine daily chest radiography is not indicated for ventilated patients in a surgical ICU. Intensive Care Med 1996,22(12):1335–1338. 10.1007/BF01709547

Clec'h C, Simon P, Hamdi A, Hamza L, Karoubi P, Fosse JP, Gonzalez F, Vincent F, Cohen Y: Are daily routine chest radiographs useful in critically ill, mechanically ventilated patients? A randomized study. Intensive Care Med 2008,34(2):264–270. 10.1007/s00134-007-0919-1

Krinsley JS: Test-ordering strategy in the intensive care unit. J Intensive Care Med 2003,18(6):330–339. 10.1177/0885066603256344

Krivopal M, Shlobin OA, Schwartzstein RM: Utility of daily routine portable chest radiographs in mechanically ventilated patients in the medical ICU. Chest 2003,123(5):1607–1614. 10.1378/chest.123.5.1607

Hejblum G, Chalumeau-Lemoine L, Ioos V, Boëlle PY, Salomon L, Simon T, Vibert JF, Guidet B: Comparison of routine and on-demand prescription of chest radiographs in mechanically ventilated adults: a multicentre, cluster-randomised, two-period crossover study. Lancet 2009,374(9702):1687–1693. 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61459-8

Oba Y, Zaza T: Abandoning daily routine chest radiography in the intensive care unit: meta-analysis. Radiology 2010,255(2):386–395. 10.1148/radiol.10090946

Ganapathy A, Adhikari NK, Spiegelman J, Scales DC: Routine chest x-rays in intensive care units: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care 2012,16(2):R68. 10.1186/cc11321

Kröner A, Binnekade JM, Graat ME, Vroom MB, Stoker J, Spronk PE, Schultz MJ: On-demand rather than daily-routine chest radiography prescription may change neither the number nor the impact of chest computed tomography and ultrasound studies in a multidisciplinary intensive care unit. Anesthesiology 2008,108(1):40–45. 10.1097/01.anes.0000296069.00566.16

Graat ME, Hendrikse KA, Spronk PE, Korevaar JC, Stoker J, Schultz MJ: Chest radiography practice in critically ill patients: a postal survey in the Netherlands. BMC Med Imaging 2006, 6: 8. 10.1186/1471-2342-6-8

Lakhal K, Serveaux-Delous M, Lefrant JY, Capdevila X, Jaber S: AzuRéa network for the RadioDay study group. Chest radiographs in 104 French ICUs: current prescription strategies and clinical value (the RadioDay study). Intensive Care Med 2012,38(11):1787–1799. 10.1007/s00134-012-2650-9

Hejblum G, Ioos V, Vibert JF, Böelle PY, Chalumeau-Lemoine L, Chouaid C, Valleron AJ, Guidet B: A web-based Delphi study on the indications of chest radiographs for patients in ICUs. Chest 2008,133(5):1107–1112. 10.1378/chest.06-3014

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

All authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

MT participated in the study design, data acquisition, data analysis, data interpretation and the writing of the manuscript. TR and MS participated in the study design and manuscript revision. PM participated in the data analysis and manuscript revision. NM participated in the study design, data analysis, data interpretation and the writing and revising of the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Tolsma, M., Rijpstra, T.A., Schultz, M.J. et al. Significant changes in the practice of chest radiography in Dutch intensive care units: a web-based survey. Ann. Intensive Care 4, 10 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/2110-5820-4-10

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/2110-5820-4-10