Abstract

Background

In areas where the morphologically indistinguishable malaria mosquitoes Anopheles gambiae Giles and An. arabiensis Patton are sympatric, hybrids are detected occasionally via species-diagnostic molecular assays. An. gambiae and An. arabiensis exhibit both pre- and post-reproductive mating barriers, with swarms largely species-specific and male F1 (first-generation) hybrids sterile. Consequently advanced-stage hybrids (back-crosses to parental species), which would represent a route for potentially-adaptive introgression, are expected to be very rare in natural populations. Yet the use of one or two physically linked single-locus diagnostic assays renders them indistinguishable from F1 hybrids and levels of interspecific gene flow are unknown.

Methods

We used data from over 350 polymorphic autosomal SNPs to investigate post F1 gene flow via patterns of genomic admixture between An. gambiae and An. arabiensis from eastern Uganda. Simulations were used to investigate the statistical power to detect hybrids with different levels of crossing and to identify the hybrid category significantly admixed genotypes could represent.

Results

A range of admixture proportions were detected for 11 field-collected hybrids identified via single-locus species-diagnostic PCRs. Comparison of admixture data with simulations indicated that at least seven of these hybrids were advanced generation crosses, with backcrosses to each species identified. In addition, of 36 individuals typing as An. gambiae or An. arabiensis that exhibited outlying admixture proportions, ten were identified as significantly mixed backcrosses, and at least four of these were second or third generation crosses.

Conclusions

Our results show that hybrids detected using standard diagnostics will often be hybrid generations beyond F1, and that in our study area around 5% (95% confidence intervals 3%-9%) of apparently ‘pure’ species samples may also be backcrosses. This is likely an underestimate because of rapidly-declining detection power beyond the first two backcross generations. Post-F1 gene flow occurs at a far from inconsequential rate between An. gambiae and An. arabiensis, and, especially for traits under strong selection, could readily lead to adaptive introgression of genetic variants relevant for vector control.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Across much of sub-Saharan Africa the major malaria vectors are Anopheles gambiae Giles, An. coluzzii Coetzee & Wilkerson and An. arabiensis Patton, members of the morphologically indistinguishable Anopheles gambiae sensu lato species complex [1]. Whilst Anopheles gambiae s.s. (henceforth An. gambiae) is the dominant malaria vector in many areas, there is evidence that in some areas in East Africa [2–5] and urban West Africa [6]An. arabiensis is increasing in relative frequency, with a concomitant potential increase in importance for malaria transmission.

The existence of previously unrecognised divisions within the An. gambiae s.l. complex were first noted over 50 years ago when crosses between field-collected samples showed that F1 males were sterile and exhibited atrophy of the testes, though F1 females were apparently viable [7]. Since males are the heterogametic sex in Anopheles this is in accordance with Haldane’s rule, a well-known form of reproductive isolation observed between recently-diverged species [8, 9]. In addition to first generation hybrid (F1) male sterility, Slotman et al. [10] demonstrated that additional inviability effects may occur, due to recessive factors located on the X chromosome of An. gambiae which are incompatible with at least one factor on each autosome of An. arabiensis. Pre-zygotic isolating mechanisms are also known: under experimental conditions the species mate assortatively [11], which could maintain reproductive isolation when An. gambiae and An. arabiensis co-occur within the same mating swarms in the wild [12] although the assortative mating cues which limit hybridisation outdoors in the wild can apparently be over-ruled when mosquitoes enter houses [13]. The cues used for species recognition remain unclear. A plausible driver of assortative mating in mixed swarms might be differing wing beat frequencies [14] although direct evidence for this is lacking [15]. The existence of both extrinsic pre-mating barriers and intrinsic post-mating barriers suggests that interspecific gene-flow could be minimal, with few F1 hybrids and a negligible level of further hybridisation by backcrossing to the parental species. Screening of field-collected samples in areas of sympatry does indeed detect hybrids at only low frequencies: 0.02-0.76% [16–18]. However, the standard single-locus diagnostics used, which both target SNPs located near the centromere of the X chromosome [19, 20], and exhibit near-perfect linkage disequilibrium [19], are incapable of discriminating F1s from backcrosses.

Whilst such data argue that advanced backcrossing between An. gambiae and An. arabiensis should be rare, evidence from both laboratory crosses and inferential data on introgression from field-collected material suggest that this can occur; in inter-specific laboratory mating, whilst there are >80% sterile males in early generations this proportion declines to around 10% after several generations (see Coz, 1973 referred to in [21]) suggesting that if backcrossing of F1s occurs, subsequent hybrid generations might largely overcome sterility barriers. In more recent laboratory interspecific crossing, introgression of shared chromosomal inversions occurred [22] though with different rates of persistence across chromosomes [23] and, in the wild, consensus of evidence suggests that the 2La inversion appears to have introgressed from the aridity-tolerant An. arabiensis to An. gambiae[24–26] and such introgression requires backcrossing. However, laboratory studies are not necessarily representative of the contemporary situation in wild populations, where interspecific mating will be much rarer, but selection (e.g. through insecticidal pressure) might drive even infrequently introgressed adaptive variation to appreciable frequencies in the recipient species [27].

Genetic analysis of field-collected material has provided indirect evidence consistent with the occurrence of contemporary or recent introgression via patterns of sharing of haplotypes at four nuclear loci [28], in mtDNA [29, 30], in the 2Rb and 2La inversions [31, 32], and from a high ratio (13:1) of shared to fixed polymorphisms located throughout the genome [33]. However, these studies provide only indirect evidence because hybrid individuals were not typed directly and/or the numbers of markers were limited. Accurate determination of the extent of admixture ideally requires large numbers of markers [34] and inclusion of individuals typing as hybrids.

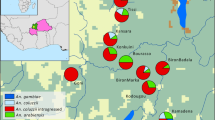

This study takes advantage of a collection of hybrid specimens detected via screening of a very large number (>7,000) of An. gambiae s.l. individuals from Eastern Uganda, where hybrids were found at a frequency of 0.22% [18]. We examine multi-locus SNP genotypes of these field-collected hybrids (N = 11) of An. gambiae and An. arabiensis and compare them to PCR-diagnostically pure forms to examine the nature of hybrid detection and interspecific gene flow.

Methods

Samples and genotyping

Samples were derived from collections in Uganda; from Jinja in 2011 [18] and Tororo in 2008 and 2009 (Weetman et al., unpublished). In total 199 An. gambiae (13 from Jinja and 186 from Tororo), 21 An. arabiensis (13 from Jinja and 8 from Tororo) and 12 individuals scored as An. gambiae x An. arabiensis hybrids (11 from Jinja and 1 from Tororo) were studied.

Species were identified using the rDNA [20] and SINE [19] species diagnostic assays. These assays type markers on the X-chromosome separated by ca. 1.4 Mb; due to the physical proximity in an area of low recombination the assays almost always yield congruent results [19]. Hybrids exhibited bands for each species at each of these assays when viewed on agarose gels. Some individuals were also genotyped using a diagnostic for the 2La inversion polymorphism [35].

Samples were genotyped using a custom 1536-SNP, Illumina GoldenGate array. We previously designed and utilised v1.0 of this array [36] to preferentially screen insecticide resistance candidate genes with ≈ 20% of the SNPs located in control, intergenic regions or non-candidate regions distributed through the genome. Version two of the array replaced consistently failing SNPs, and provided more balanced genomic coverage (Additional file 1: Figure S1 and Additional file 2: Table S1).

DNA was extracted using the DNEasy extraction kit (Qiagen) and quantified using the PicoGreen quantification kit (Invitrogen) [37]. Individual mosquitoes typically provide insufficient DNA for the GoldenGate assay [37] and therefore whole genome amplification is required. Whole genome amplification of a total of 50 ng of the extracted DNA was performed using the GenomiPhi V2 DNA amplification kit (GE Life Sciences) and quantification repeated using PicoGreen before dilution to 50 ng/μl. Template for the Illumina GoldenGate assay was 5 μl of this whole genome amplified DNA. The assay was run on an Illumina Beadstation GX following the manufacturer’s protocols. To check for possible contamination which would influence hybrid assessment, we sequenced all 12 hybrid samples and 11 An. gambiae using primers C1-J-2182 and TL2-N-3014 [38] with conditions as in [39] to amplify 800 bp of the mitochondrial COI gene, and for which no within-sample heterozygosity should be observed. From a total of 64 polymorphic bases, 22 of the 23 samples sequenced showed no heterozygosity, but one hybrid sample was heterozygous at 73% of the sites. Since this sample clearly represented a mixture of DNAs it was removed from the analysis.

Data analysis

Genotype calls were made with Beadstudio v3.2 (Illumina Inc.) with all calls checked manually. Although predominantly female samples were used (199 female An. gambiae, seven An. arabiensis from Jinja, eight An. arabiensis from Tororo and 11 hybrids), six An. arabiensis samples from Jinja (of 13) were males. Since both males and females were studied, X-chromosome SNPs were excluded from the analysis. From a total of 736 reliably scoreable SNPs on the array [36, 40], 462 autosomal SNPs were identified that were polymorphic and exhibited ≤20% missing data in any sample group (each species and hybrids). These 462 SNPs were used for all analyses (Additional file 1: Figure S1). FST and diversity statistics for each SNP were calculated from genotypes of PCR diagnostically-pure species using GenAlEx 6.5 [41], and the distance among individual multilocus genotypes visualised using principal coordinates analysis (PCoA), also using GenAlEx 6.5 [41], with default settings. Individual multilocus genotypes comprising of SNPs on chromosome 3 and chromosome arm 2R (see Results) served as input for STRUCTURE 2.3.4 [42] and BAPS 6 clustering and genomic admixture analyses [43, 44]. Though normally applied as alternatives, these two methods were used together because STRUCTURE provides estimated admixture proportions for every individual, whereas BAPS only provides admixture proportions if some evidence of mixture is detected (otherwise a zero is returned) but also provides a probability for a hypothesis of no admixture. The admixture algorithm first estimates which multilocus genotypes show evidence of mixture and the proportion of the genome attributed to each source population, followed by simulation of multilocus genotypes from allele frequencies to determine the posterior probability that putatively mixed genotypes could be found in the source population [43, 44]. For STRUCTURE, admixture was estimated from the mean of ten replicates with 10,000 iterations for burn-in and 20,000 for data-collection, with k set to two in every run (to capture each species’ samples: STRUCTURE was not applied to determine the optimum number of clusters). In BAPS, multiple runs with k set from 2 to 20 were undertaken to obtain optimum clustering solutions. Settings for the admixture analysis were 100 iterations, 200 or 1000 reference individuals for simulations (see below) for observed data, and 20 iterations for the reference individuals. Since ‘pure’ species determined by single-locus diagnostics might actually be mixed genotypes, we computed an outlier analysis for each set of ‘pure’ species data. Using the proportionate mixture estimates from all data from STRUCTURE, we calculated the absolute deviation from the grand median and multiplied by a constant (b = 1.4826) representing the normal distribution to yield a median absolute deviation metric (MAD). Outliers were considered as data points whose mixture value was more extreme than 3 × MAD (in the direction of the alternate species, which represents a conservative threshold [45]. This method has the advantage over those utilising means and standard deviations of being relatively insensitive to the influence of any outliers in the detection process [45]; calculations were performed in Excel. BAPS admixture analysis was then performed using An. arabiensis and An. gambiae, following exclusion of outliers, as predefined populations and the outliers and hybrids as the test samples.

Simulations of expected mixture proportions for various classes of hybrid were conducted in Hybridlab [46]. Observed genotype data for the ‘pure’ species samples (i.e. excluding outliers) was first used to generate 100 simulated genotypes of each, which served as the data for production of F1, F2, F3 and first to third generation backcrosses. 100 simulated genotypes were produced for each hybrid class for admixture analysis in BAPS with the simulated ‘pure’ species genotypes as predefined reference populations. To evaluate detection power for each hybrid class we calculated the percentage of significantly mixed individuals, mean admixture proportion, and its deviation from the relevant theoretical expectation: 0.5 for F1, F2, F3; 0.25 for first generation backcrosses (bx1), 0.125 for bx2, and 0.0625 for bx3. Admixture proportions of significantly mixed observed genotypes falling with the range of simulated values were considered potentially representative of the hybrid class. Thus genotypes could in some cases be considered a potential member of multiple classes, in which case their precise hybrid class status could not be determined.

Results

Dataset properties and refinement

A total of 462 autosomal SNPs could be reliably scored in both species and were polymorphic in at least one (Additional file 1: Figure S1, Additional file 2: Table S1). Whether measured as number of alleles (Na) or heterozygosity (He), diversity was much lower in An. arabiensis (mean ± 95% confidence interval: Na = 1.29 ± 0.041; He = 0.091 ± 0.015) than An. gambiae (mean ± 95% confidence interval: Na = 1.96 ± 0.018; He = 0.27 ± 0.016), likely reflecting ascertainment bias resulting from use of an array designed from An. gambiae polymorphisms. Interspecific differentiation over all loci was calculated as FST = 0.128 ± 0.014, with only one autosomal locus representing a fixed difference between the species (Additional file 2: Table S1).

Principal coordinates analysis (PCoA) clearly differentiated pure An. gambiae from An. arabiensis, with hybrids scattered in between (Figure 1). However, hybrid position with respect to the parental species was obscured by subdivision of the An. gambiae data points into three groups. Based on previous analyses [33, 36] we hypothesised that this vertical separation results from highly differentiated multilocus genotypes that reflect alternative arrangements of the 21 Mb 2La paracentric inversion on chromosome arm 2L (2La/2La, 2La/2L+a, 2L+a/2L+a). To test this we ran a BAPS clustering analysis using only loci within the 2La inversion (N = 61 SNPs). BAPS identified four clusters; two of which overlapped closely but contained a different composition of the species (Figure 1). The three major clusters (counting the overlapping clusters as one) corresponded perfectly with the diagonally-oriented clustering observed using all 462 SNPs, thus these clearly represent the three alternate 2La karyotypic combinations, which we confirmed by genotyping a portion of the individuals (N=26; 19 × 2La/2La, 5 × 2La/2L+a, 2 × 2L+a/2L+a) from across the groups using a 2La PCR diagnostic. Owing to this dependence of clustering on 2La genotypes we proceeded with subsequent analysis using only SNP data from chromosome arm 2R and both arms of chromosome 3. PCoA analysis of this reduced dataset (N = 353 polymorphic SNPs) demonstrated that the 2La genotype stratification was no longer evident (Additional file 1: Figure S2) and also that samples from the different collection locales were well mixed in clusters (Additional file 1: Figure S3), suggesting this would exert negligible impact on any subsequent analysis.

Genomic admixture and hybrid classification

Analysis of individual admixture coefficients (proportion of each 353-SNP genotype attributed as of An. arabiensis or An. gambiae in origin) estimated using STRUCTURE identified two putative An. arabiensis and 34 putative An. gambiae as outliers (Additional file 2: Table S2). In order to obtain ‘pure’ species data the outliers were excluded. Significance of genomic admixture was assessed using BAPS with ‘pure’ species genotypes (i.e. excluding outliers) as two reference datasets against which patterns of admixture were evaluated in both the outlier samples and the hybrids (pre-identified using X-linked PCR diagnostics). Both An. arabiensis outliers and 24 out of 34 of the An. gambiae outliers were not adjudged significantly mixed, but 10 out of 11 hybrids were significant, and displayed admixture proportions overlapping those of the ten significantly mixed An. gambiae outliers. Thus, hybrids formed a spectrum of admixture, and only a minority (three of 11) were close to the 50:50 that would be expected for F1 hybrids (Figure 2).

Proportion of An. gambiae genome estimated in multilocus genotypes ( N = 353 SNPs) estimated by STRUCTURE. Samples are categorised as: ‘pure’ An. gambiae or An. arabiensis from IGS and SINE diagnostics, and non-outlier status in terms of their proportions of the appropriate genome (top and bottom rows); outliers from the pure species (second and fourth rows) or hybrids (solely) from IGS and SINE diagnostics (middle row). *statistically significant genome mixture detected by BAPS; †marginally non-significant genome mixture. Note that although BAPS and STRUCTURE admixture coefficients were strongly correlated for significantly mixed individuals (Pearson’s r = 0.998, N = 22) the relationship between likelihood of significance and the estimated average level of genomic admixture is not expected to be perfect.

In order to evaluate the power of hybrid detection and to produce empirical categories to which observed data could be fitted, simulations were run in HybridLab. The expected proportions of the genome originating from each parental species and probability of detection of significant admixture were computed using BAPS for nine different cross scenarios (Figure 3). As expected, F1 hybrids are indistinguishable from advanced intercrosses (F2, F3), but power to detect intercross classes and also first generation backcrosses was 99-100% (Figure 3A) with minimal deviation of simulated admixture proportions from theoretical expectations (Figure 3B). Power to detect second generation backcrosses was much higher for crosses with An. arabiensis than An. gambiae, but was very low (<20%) for the third generation (Figure 3A) and detection strongly biased toward those exhibiting relatively greater admixture (Figure 3B).

Hybridlab results for simulation of different levels of intercrossing and backcrossing to each parental species. Simulations were undertaken for different levels of intercrossing (F) and backcrossing (bx) (A) Dots show the % of hybrids exhibiting significant genomic admixture; bars show mean genomic admixture proportions for simulated individuals detected as significantly admixed (+/- 95% confidence interval). (B) Bias in mean admixture proportion for individuals detected as significantly mixed, expressed as deviation of observed data from the theoretical expectation for the level of crossing (i.e. F1 = 0.5; first generation backcross = 0.75, etc.).

Plausible hybrid ancestries for the outliers and pre-identified hybrids are shown in Table 1 and range through all potential scenarios from F1 to advanced back-crosses, with all ten outliers identifiable as backcrosses to An. gambiae. Overall, only one third of the pre-diagnosed hybrid samples appear to represent F1 hybrids (Table 2), with confidence intervals suggesting between approximately 31-89% are likely to be backcrosses, with up to 9% of An. gambiae diagnosed as pure species by X-diagnostics (Table 2). The marginally non-significant hybrid sample most likely represents a type II error arising from poor detection power for advanced backcross genotypes with such a concomitantly low level of mixture.

Discussion

Even in the absence of intrinsic post-zygotic isolating mechanisms, selection against F1 genotypes can be strong if parental species display ecological niche segregation [47], which is at least partially true of An. gambiae s.s. and An. arabiensis[48, 49]. When coupled with male sterility, as predicted by Haldane’s rule [9], it would seem entirely possible that hybrids between these An. gambiae s.l. species might be near-ubiquitously F1s and a near dead-end for contemporary gene flow. Our results show that this is definitely not the case. Although hybrids are rare, where detected there is a 30-90% probability (confidence intervals from our data) that they will be backcrosses, some quite advanced. These results highlight that an important conduit for gene flow exists between species which could permit adaptive introgression of genetic variants [50].

Convincing demonstrations of contemporary adaptive introgression between animal species are very rare [50] though transfer of anticoagulant rodenticide resistance from Mus spretus to Mus musculus[27] - which also exhibit Haldane’s rule and are subject to strong anthropogenic selection pressure - provides a comparable, if phylogenetically-disparate, case study. Indeed transfer of the strongly-selected Vgsc-1014F mutation from An. gambiae s.s. (S form) to An. coluzzii (M form), with a subsequent dramatic increase in frequency [51], has been unambiguously demonstrated [36, 52]. An. gambiae s.s. and An. coluzzii exhibit similar partial ecological niche separation and hybrid and backcross detection rates appear broadly comparable to those found in the present study [40, 53]. Does this similarity, coupled with the results presented here mean that adaptive introgression between An. gambiae and An. arabiensis will occur, or perhaps has already done so, in response to anthropogenic selection? The An. arabiensis samples from Jinja studied here were from insecticide resistance-phenotyped specimens [18], but we have yet to identify the mechanisms involved. Kawada et al. [54] report introgression of Vgsc-1014S from An. gambiae to An. arabiensis in samples from neighbouring Kenya. Yet their sequencing of the intron downstream of Vgsc-1014S detected insufficient variation to support this conclusion, and Kawada et al.’s[54] study actually provides no evidence for introgression. The Vgsc-1014F mutation has been identified in West African An. arabiensis but this is a de novo phenomenon and not introgression from An. gambiae[55].

Adaptive introgression is likely to involve massive disruption of the recipient genome, because selection will tend to cause a sweep of an extended region of the source genome through the population as observed in both Mus domesticus and An. coluzzii[27, 51]. Such introgressed genomic regions may contain many variants that are maladaptive for the recipient genome and recombination will take time to reduce the region size to retain only the beneficial locus [50]. Though apparently selectively advantageous for An. coluzzii, this species is much more closely related to An. gambiae s.s. than is An. arabiensis[33], and thus potential for disruption of the genome may be more limited. At present we know little of the selective advantage or disadvantage experienced by the backcrosses or F1 hybrids we detected, which will require identification of a selected introgressed locus, or direct experimental testing of relative fitness. Nevertheless our results have established that the potential exists for adaptive introgression; whether this occurs will depend on the balance of the positive selective coefficient of the adaptive locus (or loci), the (assumed) negative selective coefficient of the other variants in the introgressed fragment, and the background recombination rate of the introgressed region [53].

This study was enabled by genotyping of very large numbers of each species at the single locus species-diagnostic markers to identify hybrids, and subsequent genotyping at a relatively large number of genomewide SNP markers, and directly demonstrates post-F1 gene flow between An. arabiensis and An. gambiae in the wild. Our results are consistent with indirect evidence of introgression from previous molecular genetic and cytogenetic studies [28–33] and with direct evidence of introgression from laboratory mating [23]. In spite of a relatively large number of markers genotyped, power to detect backcrossing became severely limited by the third generation and future studies of introgression will benefit from availability of whole genome sequence datasets for each species, as well as providing estimates of differentiation throughout the genome that are unaffected by the ascertainment bias observed here and evident in a previous genomewide SNP study [56]. Moreover, genotyping by sequencing should permit identification of many markers exhibiting fixed differences, which can provide a diagnostic panel to study backcrossing [57]. Here we identified only one fixed difference, which can provide little additional discrimination, because six or more fully diagnostic markers are required to statistically partition hybrids as F1s and backcrosses (based on binomial probabilities and a threshold P of 0.05).

Conclusion

Our study demonstrates unambiguously the occurrence of introgressive hybridisation between An. gambiae and An. arabiensis. To fully understand the adaptive and applied importance of this observation additional studies are required, preferably involving whole genome sequencing. The An. gambiae genome has been sequenced [58] and the An. arabiensis genome is now available [59]. These data will aid in understanding the extent of genomic differentiation and, as additional An. gambiae and An. arabiensis whole genome sequences are made available (e.g. [60]), the extent of genomic introgression will be revealed in detail.

Abbreviations

- BAPS:

-

Bayesian analysis of genetic population structure

- Kdr :

-

Knockdown resistance

- Mb:

-

Mega base pairs (=1,000,000 bp)

- mtDNA:

-

Mitochondrial DNA

- PCoA:

-

Principal coordinates analysis

- PCR:

-

Polymerase chain reaction

- rDNA:

-

Ribosomal DNA

- SINE:

-

Short interspersed nuclear element

- SNP:

-

Single nucleotide polymorphism.

References

White BJ, Collins FH, Besansky NJ: Evolution of Anopheles gambiae in relation to humans and malaria. Annu Rev Ecol Evol Syst. 2011, 42 (1): 111-132.

Bayoh MN, Mathias D, Odiere M, Mutuku F, Kamau L, Gimnig J, Vulule J, Hawley W, Hamel M, Walker E: Anopheles gambiae: historical population decline associated with regional distribution of insecticide-treated bed nets in western Nyanza Province, Kenya. Malar J. 2010, 9 (1): 62.

Lindblade KA, Gimnig JE, Kamau L, Hawley WA, Odhiambo F, Olang G, Ter Kuile FO, Vulule JM, Slutsker L: Impact of sustained use of insecticide-treated bednets on malaria vector species distribution and culicine mosquitoes. J Med Entomol. 2006, 43 (2): 428-432.

Mwangangi J, Mbogo C, Orindi B, Muturi E, Midega J, Nzovu J, Gatakaa H, Githure J, Borgemeister C, Keating J, Beier J: Shifts in malaria vector species composition and transmission dynamics along the Kenyan coast over the past 20 years. Malar J. 2013, 12 (1): 13.

Derua Y, Alifrangis M, Hosea K, Meyrowitsch D, Magesa S, Pedersen E, Simonsen P: Change in composition of the Anopheles gambiae complex and its possible implications for the transmission of malaria and lymphatic filariasis in north-eastern Tanzania. Malar J. 2012, 11 (1): 188.

Jones CM, Toé HK, Sanou A, Namountougou M, Hughes A, Diabaté A, Dabiré R, Simard F, Ranson H: Additional selection for insecticide resistance in urban malaria vectors: DDT resistance in Anopheles arabiensis from Bobo-Dioulasso, Burkina Faso. PLoS ONE. 2012, 7 (9): e45995.

Davidson G: The five-mating types in the Anopheles gambiae complex. Riv Malariol. 1964, 43: 167-183.

Schilthuizen M, Giesbers MC, Beukeboom LW: Haldane's rule in the 21st century. Heredity. 2011, 107 (2): 95-102.

Haldane JBS: Sex ratio and unisexual sterility in hybrid animals. J Genet. 1922, 12 (2): 101-109.

Slotman M, della Torre A, Powell JRI: The genetics of inviability and male sterility in hybrids between Anopheles gambiae and An. arabiensis. Genetics. 2004, 167 (1): 275-287.

Okereke TA: Hybridization studies on sibling species of the Anopheles gambiae Giles complex (Diptera, Culicidae) in the laboratory. Bull Entomol Res. 1980, 70 (3): 391-398.

Marchand RP: Field observations on swarming and mating in Anopheles gambiae mosquitoes in Tanzania. Neth J Zool. 1983, 34: 367-387.

Dao A, Adamou A, Yaro AS, Maïga HM, Kassogue Y, Traoré SF, Lehmann T: Assessment of alternative mating strategies in Anopheles gambiae: does mating occur indoors?. J Med Entomol. 2008, 45 (4): 643-652.

Wekesa JW, Brogdon WG, Hawley WA, Besansky NJI: Flight tone of field-collected populations of Anopheles gambiae and An. arabiensis (Diptera: Culicidae). Physiol Entomol. 1998, 23 (3): 289-294.

Tripet F, Dolo G, Traore S, Lanzaro GCI: The "wingbeat hypothesis" of reproductive isolation between members of the Anopheles gambiae complex (Diptera: Culicidae) does not fly. J Med Entomol. 2004, 41 (3): 375-384.

Touré YT, Petrarca V, Traoré SF, Coulibaly A, Maiga HM, Sankaré O, Sow M, Di Deco MA, Coluzzi M: Distribution of inversion polymorphism of chromosomally recognised taxa of the Anopheles gambiae complex in Mali, West Africa. Parassitologia. 1998, 40: 477-511.

Temu EA, Hunt RH, Coetzee M, Minjas JN, Shiff CJ: Detection of hybrids in natural populations of the Anopheles gambiae complex by the rDNA based, PCR method. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1997, 91 (8): 963-966.

Mawejje HD, Wilding CS, Rippon EJ, Hughes A, Weetman D, Donnelly MJ: Insecticide resistance monitoring of field-collected Anopheles gambiae s.l. populations from Jinja, eastern Uganda, identifies high levels of pyrethroid resistance. Med Vet Entomol. 2013, 27 (3): 276-283.

Santolamazza F, Mancini E, Simard F, Qi YM, Tu ZJ, della Torre A: Insertion polymorphisms of SINE200 retrotransposons within speciation islands of Anopheles gambiae molecular forms. Malaria J. 2008, 7: 63.

Scott JA, Brogdon WG, Collins FH: Identification of single specimens of the Anopheles gambiae complex by the Polymerase Chain Reaction. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1993, 49 (4): 520-529.

White GB: Anopheles gambiae complex and disease transmission in Africa. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1974, 68 (4): 278-302.

della Torre A, Merzagora L, Powell JR, Coluzzi M: Selective introgression of paracentric inversions between two sibling species of the Anopheles gambiae complex. Genetics. 1997, 146 (1): 239-244.

Slotman MA, della Torre A, Calzetta M, Powell JR: Differential introgression of chromsomal regions between Anopheles gambiae and An. arabiensis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2005, 73 (2): 326-335.

Kamali M, Xia A, Tu Z, Sharakhov IV: A new chromosomal phylogeny supports the repeated origin of vectorial capacity in malaria mosquitoes of the Anopheles gambiae complex. PLoS Pathog. 2012, 8 (10): e1002960.

Powell JR, Petrarca V, Della Torre A, Caccone A, Coluzzi MW: Population structure, speciation, and introgression in the Anopheles gambiae complex. Parassitologia. 1999, 41: 101-113.

Coluzzi M, Sabatini A, Petrarca V, Di Deco MA: Chromosomal differentiation and adaptation to human environments in the Anopheles gambiae complex. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1979, 73 (5): 483-497.

Song Y, Endepols S, Klemann N, Richter D, Matuschka F-R, Shih C-H, Nachman Michael W, Kohn Michael H: Adaptive introgression of anticoagulant rodent poison resistance by hybridization between Old World mice. Curr Biol. 2011, 21 (15): 1296-1301.

Besansky NJ, Krzywinski J, Lehmann T, Simard F, Kern M, Mukabayire O, Fontenille D, Touré Y, Sagnon NF: Semipermeable species boundaries between Anopheles gambiae and Anopheles arabiensis: evidence from multilocus DNA sequence variation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003, 100 (19): 10818-10823.

Besansky NJ, Lehmann T, Fahey GT, Fontenille D, Braack LEO, Hawley WA, Collins FH: Patterns of mitochondrial variation within and between African malaria vectors, Anopheles gambiae and An. arabiensis, suggest extensive gene flow. Genetics. 1997, 147 (4): 1817-1828.

Donnelly MJ, Pinto J, Girod R, Besansky NJ, Lehmann TI: Revisiting the role of introgression vs shared ancestral polymorphisms as key processes shaping genetic diversity in the recently separated sibling species of the Anopheles gambiae complex. Heredity. 2004, 92 (2): 61-68.

Caccone A, Min G-S, Powell JR: Multiple origins of cytologically identical chromosome inversions in the Anopheles gambiae complex. Genetics. 1998, 150 (2): 807-814.

Mukabayire O, Caridi J, Wang X, Toure YT, Coluzzi M, Besansky NJ: Patterns of DNA sequence variation in chromosomally recognized taxa of Anopheles gambiae: evidence from rDNA and single-copy loci. Insect Mol Biol. 2001, 10 (1): 33-46.

O'Loughlin SM, Magesa S, Mbogo C, Mosha F, Midega J, Lomas S, Burt A: Genomic analyses of three malaria vectors reveals extensive shared polymorphism but contrasting population histories. Mol Biol Evol. 2014, 31 (4): 889-902.

Twyford AD, Ennos RA: Next-generation hybridization and introgression. Heredity. 2012, 108 (3): 179-189.

White BJ, Santolamazza F, Kamau L, Pombi M, Grushko O, Mouline K, Brengues C, Guelbeogo W, Coulibaly M, Kayondo JK, Sharakhov I, Simard F, Petrarca V, della Torre A, Besansky NJ: Molecular karyotyping of the 2La inversion in Anopheles gambiae. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2007, 76: 334-339.

Weetman D, Wilding CS, Steen K, Morgan JC, Simard F, Donnelly MJ: Association mapping of insecticide resistance in wild Anopheles gambiae populations: major variants identified in a low-linkage disequilbrium genome. PLoS ONE. 2010, 5 (10): e13140.

Wilding CS, Weetman D, Steen K, Donnelly MJ: Accurate determination of DNA yield from individual mosquitoes for population genomic applications. Insect Sci. 2009, 16 (4): 361-363.

Simon C, Frati F, Beckenbach A, Crespi B, Liu H, Flook P: Evolution, weighting and phylogenetic utility of mitochondrial gene sequence and a compilation of conserved ploymerase chain reaction primers. Ann Entomol Soc Am. 1994, 87: 651-701.

Santos H, Rousselet J, Magnoux E, Paiva M-R, Branco M, Kerdelhué C: Genetic isolation through time: allochronic differentiation of a phenologically atypical population of the pine processionary moth. Proc Roy Soc B. 2007, 274 (1612): 935-941.

Weetman D, Wilding CS, Steen K, Pinto J, Donnelly MJ: Gene flow-dependent genomic divergence between Anopheles gambiae M and S forms. Mol Biol Evol. 2012, 29: 279-291.

Peakall R, Smouse PE: GenAlEx 6.5: genetic analysis in Excel. Population genetic software for teaching and research—an update. Bioinformatics. 2012, 28 (19): 2537-2539.

Falush D, Stephens M, Pritchard JK: Inference of population structure using multilocus genotype data: linked loci and correlated allele frequencies. Genetics. 2003, 164 (4): 1567-1587.

Corander J, Marttinen P, Mäntyniemi S: A Bayesian method for identification of stock mixtures from molecular marker data. Fishery Bulletin. 2006, 104: 550-558.

Corander J, Marttinen P, Sirén J, Tang J: Enhanced Bayesian modelling in BAPS software for learning genetic structures of populations. BMC Bioinformatics. 2008, 9 (1): 539.

Leys C, Ley C, Klein O, Bernard P, Licata L: Detecting outliers: do not use standard deviation around the mean, use absolute deviation around the median. J Exp Soc Psychol. 2013, 49 (4): 764-766.

Nielsen EE, Bach LA, Kotlicki P: Hybridlab (version 1.0): a program for generating simulated hybrids from population samples. Mol Ecol Notes. 2006, 6 (4): 971-973.

McBride CS, Singer MC: Field studies reveal strong postmating isolation between ecologically divergent butterfly populations. PLoS Biol. 2010, 8 (10): e1000529.

Costantini C, Ayala D, Guelbeogo W, Pombi M, Some C, Bassole I, Ose K, Fotsing J-M, Sagnon NF, Fontenille D, Besansky N, Simard F: Living at the edge: biogeographic patterns of habitat segregation conform to speciation by niche expansion in Anopheles gambiae. BMC Ecol. 2009, 9 (1): 16.

Simard F, Ayala D, Kamdem G, Pombi M, Etouna J, Ose K, Fotsing J-M, Fontenille D, Besansky N, Costantini C: Ecological niche partitioning between Anopheles gambiae molecular forms in Cameroon: the ecological side of speciation. BMC Ecol. 2009, 9 (1): 17.

Hedrick PW: Adaptive introgression in animals: examples and comparison to new mutation and standing variation as sources of adaptive variation. Mol Ecol. 2013, 22 (18): 4606-4618.

Lynd A, Weetman D, Barbosa S, Yawson AE, Mitchell S, Pinto J, Hastings I, Donnelly MJ: Field, genetic and modelling approaches show strong positive selection acting upon an insecticide resistance mutation in Anopheles gambiae s.s. Mol Biol Evol. 2010, 27: 1117-1125.

Weill M, Chandre F, Brengues C, Manguin S, Akogbeto M, Pasteur N, Guillet P, Raymond M: The kdr mutation occurs in the Mopti form of Anopheles gambiae s.s. through introgression. Insect Mol Biol. 2000, 9 (5): 451-455.

Clarkson CS, Weetman D, Essandoh J, Yawson AE, Maslen G, Manske M, Field SG, Webster M, Antão T, MacInnis B, Kwiatkowski D, Donnelly MJ: Adaptive introgression between Anopheles sibling species eliminates a major genomic island but not reproductive isolation. Nat Commun. 2014, 5: 4248.

Kawada H, Futami K, Komagata O, Kasai S, Tomita T, Sonye G, Mwatele C, Njenga SM, Mwandawiro C, Minakawa N, Takagi M: Distribution of a knockdown resistance mutation (L1014S) in Anopheles gambiae s.s. and Anopheles arabiensis in western and southern Kenya. PLoS ONE. 2011, 6 (9): e24323.

Diabate A, Brengues C, Baldet T, Dabire KR, Hougard JM, Akogbeto M, Kengne P, Simard F, Guillet P, Hemingway J, Chandre F: The spread of the Leu-Phe kdr mutation through Anopheles gambiae complex in Burkina Faso: genetic introgression and de novo phenomena. Trop Med Int Health. 2004, 9 (12): 1267-1273.

Neafsey DE, Lawniczak MKN, Park DJ, Redmond SN, Coulibaly MB, Traoré SF, Sagnon N, Costantini C, Johnson C, Wiegand RC, Collins FH, Lander ES, Wirth DF, Kafatos FC, Besansky NJ, Christophides GK, Muskavitch MAT: SNP genotyping defines complex gene-flow boundaries among African malaria vector mosquitoes. Science. 2010, 330 (6003): 514-517.

Lee Y, Marsden CD, Norris LC, Collier TC, Main BJ, Fofana A, Cornel AJ, Lanzaro GC: Spatiotemporal dynamics of gene flow and hybrid fitness between the M and S forms of the malaria mosquito, Anopheles gambiae. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013, 110: 19854-19859.

Holt RA, Subramanian GM, Halpern A, Sutton GG, Charlab R, Nusskern DR, Wincker P, Clark AG, Ribeiro JMC, Wides R, Salzberg SL, Loftus B, Yandell M, Majoros WH, Rusch DB, Lai ZW, Kraft CL, Abril JF, Anthouard V, Arensburger P, Atkinson PW, Baden H, de Berardinis V, Baldwin D, Benes V, Biedler J, Blass C, Bolanos R, Boscus D, Barnstead M: The genome sequence of the malaria mosquito Anopheles gambiae. Science. 2002, 298 (5591): 129-149.

Neafsey DE, Christophides GK, Collins FH, Emrich SJ, Fontaine MC, Gelbart W, Hahn MW, Howell PI, Kafatos FC, Lawson D, Muskavitch MA, Waterhouse RM, Williams LJ, Besansky NJ: The evolution of the Anopheles 16 genomes project. G3: Genes|Genomes|Genetics. 2013, 3 (7): 1191-1194.

MalariaGEN – vector: using next-generation sequencing to understand the diversity and dynamics of Anopheles populations. [http://www.malariagen.net/projects/vector]

Acknowledgments

The project was supported by Award Number U19AI089674 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) and from the National Institute of Health (NIH) grant R01AI082734-01. HDM was supported by the Uganda Malaria Clinical Operational and Health Services (COHRE) Training Program at Makerere University, Grant #D43-TW00807701A1, from the Fogarty International Center (FIC) at the National Institutes of Health (NIH). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIAID, FIC or NIH. We thank two anonymous reviewers for helpful comments on an earlier draft of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: DW, MJD, CSW. Performed the experiments: DW, KS, EJR, HDM, CSW. Wrote the manuscript DW, MJD, CSW. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

13071_2014_1535_MOESM1_ESM.docx

Additional file 1: Figure S1: Graphical representation of SNPs scored on the array and those used in the study analysis (following exclusion of monomorphic SNPs and those with higher rates of missing values). Each cross is a SNP with position representing physical position in the genome. Grey lines are divisions between chromosomes. See Additional file 2: Table S1 for a full list of SNPs. Figure S2. PCoA of autosomal SNPs (N=353) excluding those from chromosome arm 2L. The key is the same as Figure 1 (red = An. gambiae; blue = An. arabiensis; yellow = X_hybrids). Figure S3. PCoA of autosomal SNPs excluding those from chromosome arm 2L with samples split by sample site/time. (DOCX 94 KB)

13071_2014_1535_MOESM2_ESM.xlsx

Additional file 2: Table S1: SNPs used in the study and associated polymorphism and differentiation statistics. Table S2. Estimated proportion of An. gambiae genome in 353-SNP genotypes using STRUCTURE (mean and stdev of 10 runs). Outliers were classified as those samples >3 absolute deviations from the grand median (calculated separately for each species). Note that hybrids were not included in either median calculation but were classed as outliers based on deviation from either species (An. gambiae median deviations shown). (XLSX 59 KB)

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Weetman, D., Steen, K., Rippon, E.J. et al. Contemporary gene flow between wild An. gambiae s.s. and An. arabiensis. Parasites Vectors 7, 345 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-3305-7-345

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-3305-7-345