Abstract

Background

Inflammatory bowel diseases (IBD) are chronic diseases of the gastrointestinal tract. Although their pathogenesis is unclear, the combination of genetic predisposition and environmental components are believed to be the main cause of these diseases. Recently, many variants in interleukin 23 receptor (IL23R) and autophagy-related 16-like 1 (ATG16L1) genes have been associated with the disease. Our objective was to assess the frequency of ATG16L1 (T300A) and IL23R (L310P) variants in Moroccan IBD (Crohn’s disease and Ulcerative Colitis) patients and to evaluate a possible effect of these variants on disease’s phenotype and clinical course.

Methods

96 Moroccan IBD patients and 114 unrelated volunteers were genotyped for ATG16L1 (T300A) and IL23R (L310P) variants by PCR-restriction fragment length polymorphism.

Results

This is the first report on the prevalence of ATG16L1 (T300A) and IL23R (L310P) variants in a Moroccan group. We found that IL23R (L310P) variant conferred a protective effect for crohn’s disease (CD) but not ulcerative colitis (UC) patients. The presence of ATG16L1 (T300A) mutated alleles was associated with CD type but not with disease onset. In addition, the carriage of T300A variant alleles conferred a protective effect in UC.

Conclusion

Our results showed that the prevalence of ATG16L1 and IL23R variants was not significantly different between patients and controls. However a possible role of ATG16L1 (T300A) on CD phenotype was suggested.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a chronic and multifactorial disease of the gastrointestinal tract. It includes Crohn’s disease (CD), ulcerative colitis (UC) and undetermined colitis. Their etiologies remain complex and unclear involving an inadequately defined relationship between microbial insult, genetic predisposition and altered intestinal barrier permeability [1]. Several genetic studies have attempted to find out more about the molecular pathogenesis of CD and UC.

Genetic variations in genes related to innate and adaptive immunity have been implicated in IBD pathogenesis. Positive correlations were reported for Interleukin 23 receptor (IL23R) [2] and Autophagy related 16-like 1 (ATG16L1) [3, 4] genes.

IL-23 is a heterodimeric cytokine produced by activated macrophages and dendritic cells. It consists of two subunits, a p40 subunit, shared with the IL-12, and a specific IL-23 subunit called p19 [5, 6]. Studies have shown that IL-23 is involved in the initiation of the innate and adaptive immune activation that characterizes IBD. It binds a complex of IL-23R and IL-12Rβ subunits. IL-23R is predominantly expressed on activated/memory T cells, T-cell clones, natural killer’s (NK) cells and, at low levels, in monocytes, macrophages, and dendritic cell populations [7, 8]. Recent studies have shown the association of some single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in the IL-23R gene with chronic inflammatory diseases especially IBD (CD and UC). The variant L310P of IL23R gene (more frequent in controls) was reported to confer a strong protection against CD [2]. In Ulcerative colitis, the effect of this mutation seems to be insignificant [9]. In addition, Lin Z et al. suggested the role of IL23R (L310P) as a protective polymorphism in UC females [10].

Several studies have established an association between ATG16L1 and IBD in various populations. The ATG16L1 gene plays a key role in autophagy pathways. It encodes a protein widely expressed in intestinal epithelial cells, lymphocytes and macrophages and mediates resistance to intracellular pathogens such as bacteria and viral particles [11]. Hampe at al. reported an association between the T300A (c898G > A) polymorphism and Crohn’s disease [3]. Subsequent replication studies revealed divergent results.

No data were available on the frequency of the ATG16L1 and IL23R variants in the Moroccan population. Hence, we aimed to examine the association between IL23R (L310P) and ATG16L1 (T300A) polymorphisms and inflammatory bowel disease (Crohn’s disease and Ulcerative colitis) in a cohort of Moroccan patients.

Methods

Patients and controls

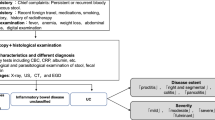

In this study, a group of 96 Moroccan unrelated IBD patients were recruited at the gastroenterology department of Averroes Hospital, Casablanca, Morocco. The control group included 114 unrelated Moroccan volunteers (blood donors) with no discernable symptoms suggestive of IBD. The diagnosis of CD or UC was based on established clinical, radiological, endoscopic, and histopathology criteria.

Demographic and clinical characteristics were obtained from the participants through a detailed questionnaire. CD phenotype was stratified by age at diagnosis, location and disease’s behaviour according to the Montreal classification [12].

For UC patients, anatomic location was subgrouped using the Paris classification as being ulcerative proctitis (E1), left-sided UC (E2), and extensive UC (E3) [13].

Differences in the frequency of disease characteristics such as age at diagnosis, gender, extra-intestinal manifestations, similar familial cases, and antecedents like appendectomy and smoking were also assessed. The study was approved by the medical school of Casablanca ethical committee. A written informed consent was obtained from all participants or their guardians. Both IBD patients and control group are originated from the different regions of Morocco and confirmed the Moroccan origin of their parents and grandparents.

Genotyping methods

Genomic DNA was isolated from whole blood samples by salting-out method [6]. DNA amount and quality were measured by spectrophotometry. IL23R and ATG16L1 variants genotyping was performed using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis (RFLP) as described respectively by Lin et al. and Csöngei et al. [10, 14].

Reactions were performed in a final volume of 25 μl. PCR products were cleaved with Hph I (L310P) and Lwe I (T300A) (New England Biolabs Ipswich, UK) and electrophored on a 3% agarose gel in the presence of a molecular weight marker ladder 100 (New England Biolabs Ipswich, UK). After staining with ethidium bromide, Ultraviolet was used on a transilluminator for reading the gel.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using MedCalc statistical software version 11.6. The Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium test was performed separately for patients and controls to measure the distribution of polymorphisms. The association between IBD (CD and UC) and IL23R (L301P) ATG16L1 (T300A) genotypes was determined by Fisher's exact test (Odds Ratio with Confidence interval (CI) at 95%). The χ2 test or Fisher test was used to correlate the IL23R and ATG16L1 polymorphisms and clinical parameters. The P value (<0.05) was considered statistically significant in all variables.

Results

Epidemiologic data

One hundred fourteen participants from the general population were genotyped for ATG16L1 (T300A) and IL23R (L310P) along with 69 Crohn’s disease patients (25 women and 44 men) and 30 UC patients (14 women and 16 men). The average age of diagnosis was 24.17 ± 2.48 for CD patients and 35.37 ± 5 for UC patients. For control group, epidemiological and clinical data are shown in Additional file 1: Table S1.

Genetic and clinical correlations

Statistical analysis of the distribution of SNPs studied showed that allele frequencies were conformed to Hardy–Weinberg expectations (=1.14, P = 0.57; =0.017, P = 0.99) (=0.03, P = 0.86; =0.017, P = 0.99) for T300A (ATG16L1) and L310P (IL23R) in CD patients and controls respectively.

Correlation between demographic and clinical characteristics according to ATG16L1 and IL23R genotypes (Tables 1 and 2) revealed a positive association between CD Type and ATG16L1 polymorphism (T300A) with P = 0.03 (Table 1). However, no genotype-phenotype correlation was noticed for the IL23R SNP.

Case–control studies were carried out for the selected polymorphisms. The genotypic and allelic frequencies for the T300A and L310P polymorphisms are presented in Tables 3 and 4 respectively.

The non-synonymous polymorphism, rs2241880 (Thr300Ala), located on the ATG16L1 gene, showed no significantly increased risk of CD among individuals carrying GG genotype or G allele with the respective odds ratio 2.08 (CI: 0.70-6.17, P = 0.19); 1.22 (CI: 0.79-1.86, P = 0.36) (Table 5). In addition, individuals carrying the mutated allele are not protected from the disease. In contrast to the L310P polymorphism in IL23R gene, which confers protection to individuals with the TT genotype and T allele against the development of Crohn’s disease, with respective odds ratio 0.26 (CI: 0.01-5.19, P = 0.38) and 0.74 (CI: 0.31-1.73, P = 0.48) (Table 4).

Additionally, our study assessed the association of ATG16L1 (T300A) and IL23R (L310P) polymorphisms with UC. Analysis of distribution of the two polymorphisms showed that allele frequencies were in Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (=1.76, P = 0.41 and =0.017, P = 0.99) for ATG16L1 and IL23R (=2.9, P = 0.23; =0.017, P = 0.99).

For both polymorphisms, no genotype-phenotype correlation was observed in UC (Tables 5 and 6).

The genotypic and allelic frequencies did not significantly differ between UC patients and healthy controls for the two polymorphisms (Tables 7 and 8).

Carriers of mutated allele in ATG16L1 gene have a protective effect for UC, with an odds ratio of 0.90 (CI: 0.50-1.61, P = 0.72) (Table 7). While carriers of mutated allele in IL23R gene are not protected from UC, with an OR of 2.10 (CI: 0.92-4.77, P = 0.08) (Table 8).

Discussion

ATG16L1polymorphism

The association of genes within the autophagy pathway with IBD was observed in several studies. One of the prime candidate genes discovered was the ATG16L1 gene, ATG16L1 is a protein expressed in the colon, leukocytes, intestinal epithelial cells, small intestine, and spleen [15]. A mutation on the gene encoding this protein, located on chromosome 2, has been associated with the onset of ileal CD [16]. It has been shown that ATG16L is a key molecule in elucidating the genetic aspects of CD. The findings of associations with variants in ATG16L1 and IBD have prompted further research on understanding the role of the autophagy pathway in disease pathogenesis.

During a genome-wide survey of 19 779 non-synonymous single nucleotide polymorphisms, the (Thr300Ala) variant, located at the N terminus of the WD-repeat domain in ATG16L1, was found to be highly associated with CD by using a haplotype and regression analysis [3]. Subsequent to the initial genome wide association study, many studies have consistently identified associations between the ATG16L1 (Thr300Ala) variant and CD [17, 18]. This finding has been widely replicated in different populations [19–32].

In the present study, we examined the association of ATG16L1 (T300A) genetic variant with CD and UC in Moroccan patients and controls. Upon association analysis, we were not able to establish a significant effect on CD risk in Moroccan IBD cohort. Our result was in concordance with the lack of association reported in a replication study performed in Japan [33]. In addition, Van Limbergen et al. [34] observed that the ATG16L1 variant is associated with susceptibility to adult CD, but not with early-onset disease in a Scottish cohort.

Regarding UC, a protective effect of this polymorphism was identified. At present, it can only be speculated how ATG16L1 T300A variant may confers risk or protection from infection, depending on the nature of the pathogen and the typical duration of infection. The cellular expression of ATG16L1 facilitates bacterial invasion, however the IBD-associated ATG16L1 T300A variant may be protective against bacterial infection.

Messer et al. demonstrated that Intestinal epithelial cells somatically targeted to express the ATG16L1 T300A variant show protection against invasion by Salmonella [23].

IL23R polymorphism

The IL23R gene is another potential candidate gene for CD risk [2, 35]. IL-23R interacts with IL-23, which is a cytokine that orchestrates intestinal inflammation via multiple pathways. It regulates the activity of immune cells and plays an important role in the inflammatory response against infection by bacteria and viruses [36]. The IL-23-IL17 axis is a key pathogenic mechanism that mediates the development and progress of inflammation by Th-17 cells. The role of the IL23-IL17 axis in IBD was supported in human patients and animal models of colitis [37–39]. Similarly, several studies have pinpointed IL23 receptor as a key pathway in the pathogenesis of inflammatory bowel disease. It was confirmed by the genetic association of several SNPs throughout the IL23R gene with CD and UC [21, 22, 24–27, 30, 32, 40–43].

It was hypothesized that IL23R gene variants have a differential effect on Th17 cells with increased Th17 cytokine secretion in patients with CD-associated IL23R variants and decreased cytokine secretion in patients with CD-protective IL23R variants [44].

In the present study, carriage of the variant allele was associated with a protective effect for CD patients, similarly to previously reported studies [45, 46]. We further analyzed whether the risk factor in the IL23R gene was also shared by UC patients and did not detect a significant association. Our subgroup analyses are likely underpowered for revealing a genotype– phenotype relationship. This result confirms previous studies on Italian [47] and North American populations [42].

Conclusion

In summary, the present study seems to indicate that ATG16L1 plays an important role in CD behaviour and confers protection for UC. In addition, IL23R gene showed a protective effect for individuals with the TT genotype and T allele against the development of Crohn’s disease.

Therefore, our results could reinforce the notion of a different relevance of ATG16L1 and IL23R in the pathogenesis of IBD in patients of different ethnic origin, with a limited role in the Moroccan population. Due to small sample size, an association cannot be ruled out. Further studies in larger groups would be required to confirm these findings.

References

Peeters M, Ghoos Y, Maes B, Hiele M, Geboes K, Vantrappen G, Rutgeerts P: Increased permeability of macroscopically normal small bowel in Crohn’s disease. Dig Dis Sci. 1994, 39: 2170-2176. 10.1007/BF02090367. doi:10.1007/BF02090367

Duerr RH, Taylor KD, Brant SR, Rioux JD, Silverberg MS, Daly MJ, Steinhart AH, Abraham C, Regueiro M, Griffiths A, Dassopoulos T, Bitton A, Yang H, Targan S, Datta LW, Kistner EO, Schumm LP, Lee AT, Gregersen PK, Barmada MM, Rotter JI, Nicolae DL, Cho JH: A genome-wide association study identifies IL23R as an inflammatory bowel disease gene. Science. 2006, 314: 1461-1463. 10.1126/science.1135245. doi:10.1126/science.1135245

Hampe J, Franke A, Rosenstie P, Till A, Teuber M, Huse K, Albrecht M, Mayr G, De La Vega FM, Briggs J, Günther S, Prescott NJ, Onnie CM, Häsler R, Sipos B, Fölsch UR, Lengauer T, Platzer M, Mathew CG, Krawczak M, Schreiber S: A genome-wide association scan of nonsynonymous SNPs identifies a susceptibility variant for Crohn disease in ATG16L1. Nat Genet. 2007, 39: 207-211. 10.1038/ng1954. doi:10.1038/ng1954

Rioux JD, Xavier RJ, Taylor KD, Silverberg MS, Goyette P, Huett A, Green T, Kuballa P, Barmada MM, Datta LW, Shugart YY, Griffiths AM, Targan SR, Ippoliti AF, Bernard EJ, Mei L, Nicolae DL, Regueiro M, Schumm LP, Steinhart AH, Rotter JI, Duerr RH, Cho JH, Daly MJ, Brant SR: Genome-wide associationstudy identifies new susceptibility loci for Crohn disease andimplicates autophagy in disease pathogenesis. Nat Genet. 2007, 39: 596-604. 10.1038/ng2032. doi:10.1038/ng2032

Fitch E, Harper E, Skorcheva I, Kurtz SE, Blauvelt A: Pathophysiology of psoriasis: recent advances on IL-23 and Th17 cytokines. CurrRheumatol Rep. 2007, 9: 461-7.

Mc Govern D, Powrie F: The IL-23 axis plays a key role in the pathogenesis of IBD. Gut. 2007, 56: 1333-1336. 10.1136/gut.2006.115402. doi:10.1136/gut.2006.115402

Yen D, Cheung J, Scheerens H, Poulet F, McClanahan T, McKenzie B, Kleinschek MA, Owyang A, Mattson J, Blumenschein W, Murphy E, Sathe M, Cua DJ, Kastelein RA, Rennick D: IL-23 is essential for T cell-mediated colitis and promotes inflammation via IL-17 and IL-6. J Clin Invest. 2006, 116: 1310-1316. 10.1172/JCI21404. doi:10.1172/JCI21404

Parham C, Chirica M, Timans J, Vaisberg E, Travis M, Cheung J, Pflanz S, Zhang R, Singh KP, Vega F, To W, Wagner J, O’Farrell AM, McClanahan T, Zurawski S, Hannum C, Gorman D, Rennick DM, Kastelein RA, de Waal MR, Moore KW: A receptor for the heterodimeric cytokine IL-23 is composed of IL-12Rbeta1 and a novel cytokine receptor subunit, IL-23R. J Immunol. 2002, 168: 5699-5708. 10.4049/jimmunol.168.11.5699.

Cummings JR, Ahmad T, Geremia A, Beckly J, Cooney R, Hancock L, Pathan S, Guo C, Cardon LR, Jewell DP: Contribution of the novel inflam-matory bowel disease gene IL-23R to disease susceptibility and phenotype. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2007, 13: 1063-8. 10.1002/ibd.20180. doi:10.1002/ibd.20180

Lin Z, Poritz L, Franke A, Li TY, Ruether A, Byrnes KA, Wang Y, Gebhard AW, MacNeill C, Thomas NJ, Schreiber S, Koltun WA: Genetic association of nonsynonymous variants of the IL23R with familial and sporadic inflammatory bowel disease in women. Dig Dis Sci. 2010, 55 (3): 739-746. 10.1007/s10620-009-0782-8. Epub 2009 Mar 18. doi:10.1007/s10620-009-0782-8

Stappenbeck TS, Rioux JD, Mizoguchi A, Saitoh T, Huett A, Darfeuille-Michaud A, Wileman T, Mizushima N, Carding S, Akira S, Parkes M, Xavier RJ: Crohn disease: a current perspective on genetics, autophagy and immunity. Autophagy. 2011, 7 (4): 355-374. 10.4161/auto.7.4.13074. doi.10.4161/auto.7.4.13074

Satsangi J, Silverberg MS, Vermeire S, Colombel JF: The Montreal classification of inflammatory bowel disease: controversies, consensos, and implications. Gut. 2006, 55 (6): 749-753. 10.1136/gut.2005.082909.

Levine A, Griffiths A, Markowitz J, Wilson DC, Turner D, Russell RK, Fell J, Ruemmele FM, Walters T, Sherlock M, Dubinsky M, Hyams JS: Pediatric Modification of the Montreal Classification for Inflammatory Bowel Disease: The Paris Classification. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011 Jun, 17 (6): 1314-21. 10.1002/ibd.21493. doi:10.1002/ibd.21493

Csöngei V, Járomi L, Sáfrány E, Sipeky C, Magyari L, Faragó B, Bene J, Polgár N, Lakner L, Sarlós P, Varga M, Melegh B: Interaction of the major inflammatory bowel disease susceptibility alleles in Crohn’s disease patients. World J Gastroenterol. 2010, 16 (2): 176-83. 10.3748/wjg.v16.i2.176. doi:10.3748/wjg.v16.i2.176

Fujita N, Itoh T, Omori H, Fukuda M, Noda T, Yoshimori T: The Atg16L complex specifies the site of LC3 lipidation for membrane biogenesis in autophagy. MolBiol Cell. 2008, 19: 2092-2100. doi:10.1091/mbc.E07-12-1257

Sventoraityte J, Zvirbliene A, Franke A, Kwiatkowski R, Kiudelis G, Kupcinskas L, Schreiber S: NOD2, IL23R and ATG16L1 polymorphisms in Lithuanian patients with in-flammatory bowel disease. World J Gastroenterol. 2010, 16: 359-364. 10.3748/wjg.v16.i3.359. doi:10.3748/wjg.v16.i3.359

Rioux JD, Xavier RJ, Taylor KD, Silverberg MS, Goyette P, Huett A, Green T, Kuballa P, Barmada MM, Datta LW, Shugart YY, Griffiths AM, Targan SR, Ippoliti AF, Bernard EJ, Mei L, Nicolae DL, Regueiro M, Schumm LP, Steinhart AH, Rotter JI, Duerr RH, Cho JH, Daly MJ, Brant SR: Genome-wide association study identifies new susceptibility loci for Crohn disease and implicates autophagy in disease pathogenesis. Nat Genet. 2007, 39: 596-604. 10.1038/ng2032. doi:10.1038/ng2032

Barrett JC, Hansoul S, Nicolae DL, Cho JH, Duerr RH, Rioux JD, Brant SR, Silverberg MS, Taylor KD, Barmada MM, Bitton A, Dassopoulos T, Datta LW, Green T, Griffiths AM, Kistner EO, Murtha MT, Regueiro MD, Rotter JI, Schumm LP, Steinhart AH, Targan SR, Xavier RJ, Genetics Consortium NIDDKIBD, Libioulle C, Sandor C, Lathrop M, Belaiche J, Dewit O, Gut I, et al: Genome-wide association defines more than 30 distinct susceptibility loci for Crohn’s disease. Nat Genet. 2008, 40: 955-962. 10.1038/ng.175. doi:10.1038/ng.175

Parkes M, Barrett JC, Prescott NJ, Tremelling M, Anderson CA, Fisher SA, Roberts RG, Nimmo ER, Cummings FR, Soars D, Drummond H, Lees CW, Khawaja SA, Bagnall R, Burke DA, Todhunter CE, Ahmad T, Onnie CM, McArdle W, Strachan D, Bethel G, Bryan C, Lewis CM, Deloukas P, Forbes A, Sanderson J, Jewell DP, Satsangi J, Mansfield JC, Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium, et al: Sequence variants in the autophagy gene IRGM and multiple other replicating loci contribute to Crohn’s disease susceptibility. Nat Genet. 2007, 39: 830-832. 10.1038/ng2061. doi:10.1038/ng2061

Cummings JR, Cooney R, Pathan S, Anderson CA, Barrett JC, Beckly J, Geremia A, Hancock L, Guo C, Ahmad T, Cardon LR, Jewell DP: Confirmation of the role of ATG16L1 as a Crohn’s disease susceptibility gene. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2007, 13: 941-946. 10.1002/ibd.20162. doi:10.1002/ibd.20162

Newman WG, Zhang Q, Liu X, Amos CI, Siminovitch KA: Genetic variants in IL-23R and ATG16L1 independently predispose to increased susceptibility to Crohn’s disease in a Canadian population. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2009, doi:10.1097/MCG.0b013e318168bdf0

Weersma RK, Stokkers PC, van Bodegraven AA, van Hogezand RA, Verspaget HW, de Jong DJ, van der Woude CJ, Oldenburg B, Linskens RK, Festen EA, van der Steege G, Hommes DW, Crusius JB, Wijmenga C, Nolte IM, Dijkstra G, Dutch Initiative on Crohn and Colitis (ICC): Molecular prediction of disease risk and severity in a large Dutch Crohn’s disease cohort. Gut. 2009, 58: 388-395. 10.1136/gut.2007.144865. doi:10.1136/gut.2007.144865

Messer JS, Murphy SF, Logsdon MF, Lodolce JP, Grimm WA, Bartulis SJ, Vogel TP, Burn M, Boone DL: The Crohn’s disease: associated ATG16L1 variant and Salmonella invasion. BMJ Open. 2013, 3: e002790-

Weersma RK, Stokkers PC, Cleynen I, Wolfkamp SC, Henckaerts L, Schreiber S, Dijkstra G, Franke A, Nolte IM, Rutgeerts P, Wijmenga C, Vermeire S: Confirmation of multiple Crohn’s disease susceptibility loci in a large Dutch-Belgian cohort. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009, 104: 630-638. 10.1038/ajg.2008.112. doi:10.1038/ajg.2008.112

Roberts RL, Gearry RB, Hollis-Moffatt JE, Miller AL, Reid J, Abkevich V, Timms KM, Gutin A, Lanchbury JS, Merriman TR, Barclay ML, Kennedy MA: IL23R R381Q and ATG16L1 T300A are strongly associated with Crohn’s disease in a study of New Zealand Caucasians with inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007, 102: 2754-2761. 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01525.x. 13 doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01525.x

Okazaki T, Wang MH, Rawsthorne P, Sargent M, Datta LW, Shugart YY, Bernstein CN, Brant SR: Contributions of IBD5, IL23R, ATG16L1 and NOD2 to Crohn’s disease risk in a population based case–control study: evidence of gene-gene interaction. InflammBowel Dis. 2008, doi:10.1002/ibd.23056

Lakatos PL, Szamosi T, Szilvasi A, Molnar E, Lakatos L, Kovacs A, Molnar T, Altorjay I, Papp M, Tulassay Z, Miheller P, Papp J, Tordai A, Andrikovics H, Hungarian IBD Study Group: ATG16L1 and IL23 receptor (IL23R) genes are associated with disease susceptibility in Hungarian CD patients. Dig Liv Dis. 2008, doi:10.1016/j.dld.2008.03.022

Fowler EV, Doecke J, Simms LA, Zhao ZZ, Webb PM, Hayward NK, Whiteman DC, Florin TH, Montgomery GW, Cavanaugh JA, Radford-Smith GL: ATG16L1 T300A shows strong associations with disease subgroups in a large Australian IBD population: further support for significant disease heterogeneity. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008, 103: 1-8. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2008.02023.x

Glas J, Konrad A, Schmechel S, Dambacher J, Seiderer J, Schroff F, Wetzke M, Roeske D, Török HP, Tonenchi L, Pfennig S, Haller D, Griga T, Klein W, Epplen JT, Folwaczny C, Lohse P, Göke B, Ochsenkühn T, Mussack T, Folwaczny M, Müller-Myhsok B, Brand S: The ATG16L1 gene variants rs2241879 and rs2241880 (T300A) are strongly associated with susceptibility to Crohn’s disease in the German population. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008, 103 (3): 682-91. 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01694.x. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01694.x

Weersma RK, Zhernakova A, Nolte IM, Lefebvre C, Rioux JD, Mulder F, van Dullemen HM, Kleibeuker JH, Wijmenga C, Dijkstra G: ATG16L1 and IL23R are associated with inflammatory bowel disease but not with celiac disease in the Netherlands. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008, 103: 621-627. 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01660.x. 14. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01660.x

The Wellcome Trust Case Control Consortium: Genome-wide association study of 14,000 cases of seven common diseases and 3000 shared controls. Nature. 2007, 447: 661-678. 10.1038/nature05911. doi:10.1038/nature05911

Latiano A, Palmieri O, Valvano MR, D'Incà R, Cucchiara S, Riegler G, Staiano AM, Ardizzone S, Accomando S, de Angelis GL, Corritore G, Bossa F, Annese V: Replication of interleukin 23 receptor and autophagy-related 16-like 1 association in adult and pediatric-onset inflammatory bowel disease in Italy. World J Gastroenterol. 2008, 14: 4643-4651. 10.3748/wjg.14.4643. doi:10.3748/wjg.14.4643

Yamazaki K, Onouchi Y, Takazoe M, Kubo M, Nakamura Y, Hata A: Association analysis of genetic variants in IL23R, ATG16L1 and 5p13.1 loci with Crohn’s disease in Japanese patients. J Hum Genet. 2007, 52: 575-583. 10.1007/s10038-007-0156-z.

Van Limbergen J, Russell RK, Nimmo ER, Drummond HE, Smith L, Anderson NH, Davies G, Gillett PM, McGrogan P, Weaver LT, Bisset WM, Mahdi G, Arnott ID, Wilson DC, Satsangi J: Autophage gene ATG16L1 influences susceptibility and disease location but not childhood- onset in Crohn’s disease in Northern Europe. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008, 14: 338-346. 10.1002/ibd.20340. doi:10.1002/ibd.20340

Libioulle C, Louis E, Hansoul S, Sandor C, Farnir F, Franchimont D, Vermeire S, Dewit O, de Vos M, Dixon A, Demarche B, Gut I, Heath S, Foglio M, Liang L, Laukens D, Mni M, Zelenika D, Van Gossum A, Rutgeerts P, Belaiche J, Lathrop M, Georges M: Novel Crohn disease locus identi¬fied by genome-wide association maps to a gene desert on 5p13.1 and modulates expression of PTGER4. PLoS Genet. 2007, 3: e58-10.1371/journal.pgen.0030058.

Medzhitov R: Recognition of microorganisms and activation of the immune response. Nature. 449: 819-826. (18 October 2007) doi:10.1038/nature06246

Sarra M, Pallone F, Macdonald TT, Monteleone G: IL-23/IL-17 axis in IBD. Inflammatory Bowel Diseases:. 2010, 16 (10): 1808-1813. 10.1002/ibd.21248. doi:10.1002/ibd.21248

McGovern D, Powrie F: The IL23 axis plays a key role in the pathogenesis of IBD. Gut. 2007, 56 (10): 1333-1336. 10.1136/gut.2006.115402. doi:10.1136/gut.2006.115402

Yamada H: Current perspectives on the role of IL-17 in autoimmune disease. J Inflamm Res. 2010, 3: 33-44.http://dx.doi.org/10.2147/JIR.S6375,

Taylor KD, Targan SR, Mei L, Ippoliti AF, McGovern D, Mengesha E, King L, Rotter JI: IL23R haplotypes provide a large population attributable risk for Crohn’s disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2008, 14: 1185-1191. 10.1002/ibd.20478. doi:10.1002/ibd.20478

Amre DK, Mack D, Israel D, Morgan K, Lambrette P, Law L, Grimard G, Deslandres C, Krupoves A, Bucionis V, Costea I, Bissonauth V, Feguery H, D'Souza S, Levy E, Seidman EG: Association between genetic variants in the IL-23R gene and early-onset Crohn’s disease: results from a case–control and family-based study among Canadian children. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008, 103: 615-620. 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01661.x. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01661.x

Tremelling M, Cummings F, Fisher SA, Mansfield J, Gwilliam R, Keniry A, Nimmo ER, Drummond H, Onnie CM, Prescott NJ, Sanderson J, Bredin F, Berzuini C, Forbes A, Lewis CM, Cardon L, Deloukas P, Jewell D, Mathew CG, Parkes M, Satsangi J: IL23R variation determines susceptibility but not disease phenotype in inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2007, 132: 1657-1664. 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.02.051. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2007.02.051

Baptista ML, Amarante H, Picheth G, Sdepanian VL, Peterson N, Babasukumar U, Lima HC, Kugathasan S: CARD15 and IL23R influences Crohn’s disease susceptibility but not disease phenotype in a Brazilian population. InflammBowel Dis. 2008, 14: 674-679. doi:10.1002/ibd.20372

Schmechel S, Konrad A, Diegelmann J, Glas J, Wetzke M, Paschos E, Lohse P, Göke B, Brand S: Linking genetic susceptibility to Crohn’s disease with Th17 cell function: IL‒22 serum levels are increased in Crohn’s disease and correlate with disease activity and IL23R genotype status. Inflammatory bowel diseases. 2008, 14 (2): 204-212. 10.1002/ibd.20315.

Oliver J, Rueda B, López-Nevot MA, Gómez-García M, Martín J: Replication of an association between IL23R gene polymorphism with inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007, 5: 977-981. 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.05.002. 981.e1-2. doi:10.1016/j.cgh.2007.05.002

Büning C, Schmidt HH, Molnar T, De Jong DJ, Fiedler T, Bühner S, Sturm A, Baumgart DC, Nagy F, Lonovics J, Drenth JP, Landt O, Nickel R, Büttner J, Lochs H, Witt H: Heterozygosity for IL23R p.Arg381Gln confers a protective effect not only against Crohn’s disease but also ulcerative colitis. Aliment PharmacolTher. 2007, 26: 1025-1033. 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03446.x. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03446.x

Perricone C, Borgiani P, Romano S, Ciccacci C, Fusco G, Novelli G, Biancone L, Calabrese E, Pallone F: ATG16L1 Ala197Thr is not associated with susceptibility to Crohn’s disease or with phenotype in an Italian population. Gastroenterology. 2008 Jan, 134 (1): 368-70. 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.11.017. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2007.11.017

Acknowledgments

We would like thank all the patients and their families for their time and participation. Our gratitude goes also to the clinicians and all the staff of gastroenterology department of CHU Ibn Rochd for their assistance in data and sample collection.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contribution

NS and NS carried out the molecular genetic studies, recruited the patients and drafted the manuscript. BD performed the statistical analysis. WB participated in the design of the study and the recruitment of patients. SN conceived the study, participated in its design and coordination and helped to draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Nadia Serbati, Nezha Senhaji contributed equally to this work.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Serbati, N., Senhaji, N., Diakite, B. et al. IL23R and ATG16L1 variants in Moroccan patients with inflammatory bowel disease. BMC Res Notes 7, 570 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-0500-7-570

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1756-0500-7-570