Abstract

Introduction

Chondral fracture of the knee is relatively rare and the optimal treatment option for this injury is still controversial. In this report, we present the case of a patient with this injury who was treated surgically using the bone peg fixation procedure. There has been no literature reporting the use of this technique for fixation of a detached chondral fragment.

Case presentation

The patient was a 14-year-old Japanese boy who sustained a knee injury while kicking a soccer ball. Although routine radiographs showed no abnormality, magnetic resonance imaging showed a large full-thickness chondral defect in the weight-bearing portion of his lateral femoral condyle and a detached chondral fragment in the anterior region. The size of the defect (fragment) was 2cm by 1.5cm. At surgery, the chondral fragment was fixed with eight cortical bone pegs that were harvested from the anteromedial aspect of his tibia.

Conclusions

The postoperative magnetic resonance imaging at 4 months and the second-look arthroscopy at 12 months revealed apparent healing of the fragment. In the final follow-up examination at 26 months, a physical examination showed no swelling with recovery of full range of motion, and he could play soccer at the pre-injury level with no complaint. Based on the clinical course of this patient, it is thought that bone peg fixation can be a valuable option for fixation of a large chondral fracture of the knee.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Chondral fracture of the femoral condyle is relatively rare and predominantly encountered as a sports-related injury in adolescence due to inferior mechanical properties of the bone–cartilage junction in this age range [1–3]. Impact of the patellar facet or tibial plateau against the femoral condyle during a twisting type of injury is thought to be an injury mechanism [2–6]. Since chondral fragments do not show up in routine radiographs, this injury may not be correctly diagnosed at the initial presentation; however, careful assessment of magnetic resonance images (MRI) can reveal chondral loose bodies as well as full-thickness defects on the articular surface. This injury often extends over a large area, and sometimes involves the weight-bearing portion [4–6]. For large lesions in the weight-bearing portion, restoration of cartilaginous integrity by internal fixation of the chondral fragment should be considered a treatment option. Regarding the surgical procedure, metal and bioabsorbable devices have been utilized to fix the intra-articular fragment in previous studies [2, 4–7]; however, a metal device requires subsequent removal in a secondary surgery, while use of a bioabsorbable material within the joint may induce a foreign body reaction in the process of degradation and reabsorption [8–10]. As an alternative option, bone peg fixation of the intra-articular osteochondral fragment has been reported with favorable results in patients with osteochondritis dissecans [11–13]. Use of the bone peg affords rigid fixation and may provide an additional advantage of biological healing enhancement; however, there has been no literature reporting the use of this technique for fixation of a detached chondral fragment.

In this report, we present the clinical characteristics and outcome of a patient with a chondral fracture in the weight-bearing region of his lateral femoral condyle who was successfully treated with bone peg fixation.

Case presentation

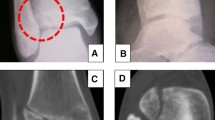

The review board of our institute approved this study, and an appropriate written informed consent was obtained from the patient and his family. A 14-year-old Japanese boy presented with pain and swelling in his right knee. He sustained an injury a month ago while kicking a soccer ball with his left leg. Following the injury, he first consulted a local clinic and was then referred to our hospital due to persistent symptoms.At his initial visit to our hospital, a physical examination showed mild effusion and limited extension without signs of ligamentous or meniscal injuries. A radiographic examination showed no abnormal findings such as fracture and malalignment. However, MRI revealed a large, full-thickness chondral defect in the weight-bearing portion of his lateral femoral condyle and a detached fragment with a length of 2cm in the anterior region (Figure 1). No other findings indicating bony or soft tissue injuries were detected on MRI. Based on these clinical and image findings, a diagnosis was made for detached chondral fracture of the lateral femoral condyle. Considering the size and location (weight-bearing area) of the injury, open reduction and internal fixation of the fragment was selected as a treatment option.Surgery was performed 6 weeks after the injury. Arthroscopic examination prior to arthrotomy showed a large, full-thickness chondral defect of his lateral femoral condyle as well as a chondral fragment of corresponding size (Figure 2A). There were no other intra-articular injuries found in arthroscopy. Thereafter, lateral parapatellar arthrotomy was performed. The size of the loose body was 2cm by 1.5cm and no bony portion was attached to the fragment (Figure 2B). Subsequently, eight cortical bone pegs (each 2mm in diameter and 15mm in length) were harvested from the anteromedial aspect of the proximal tibia. Following the removal of the thin tissue covering the surface of his chondral defect (Figure 3A), the chondral fragment was fixed back to his subchondral bone using the bone pegs. The fragment fit into the defect well and an apparently smooth articular surface was restored with firm fixation achieved (Figure 3B).

Postoperatively, his operated knee was immobilized in a cylinder cast for 3 weeks and passive range of motion was started thereafter. Partial weight bearing was allowed at 5 weeks with progression to full weight bearing at 8 weeks. Considering the location of the chondral fracture (contact position at flexion), use of a hinged brace with an extension blocking mechanism was instructed while walking to avoid the application of excessive load to the fixed fragment.The postoperative MRI performed at 4 months showed continuity of the articular surface, which suggested the progression of healing with maintenance of reduction (Figure 4). After confirmation of the apparent healing on MRI, he began jogging at 5 months and return to strenuous sport activities was permitted at 7 months. In order to directly confirm the healing status of the fixed fragment, a second-look arthroscopy was performed at 12 months. In the arthroscopic examination, the chondral fragment appeared firmly united to the underlying bone with restoration of a smooth articular surface (Figure 5). The patient could play soccer at a pre-injury level with no complaint at the final follow-up visit at 26 months.

Discussion

Chondral fracture of the knee is a relatively uncommon injury. In 1985, Hopkinson et al.[2] reviewed their patient records and reported that chondral fractures were identified in eight of the 1095 knees (0.73%) arthroscoped at their institute. In accordance with the routine use of MRI as a part of the examination for knees with sports injuries, diagnostic accuracy for chondral injury has been improved and the incidence of this injury in our current practice is thought to be higher than the value in previous reports.

Regarding the injury mechanism of chondral fractures, Flachsmann et al. [1] conducted a biomechanical study using bovine cartilage bone laminates. They compared the strength of the osteochondral junction among the different maturation stages and showed that adolescent tissue exhibited significantly reduced fracture toughness under shear loading. Therefore, shear loading at the articular contact during a twisting injury is thought to be a predominant injury mechanism. Since the chondral defect in the reported case was located at the mid-lateral articular edge, patella-femoral contact during shifting motion of the patella may have been a mechanism of the injury. Mashoof et al.[4] reported seven cases with osteochondral injuries to this location that were associated with patella dislocation.

Chondral fractures with detached fragments require surgical intervention. Surgical options include removal and fixation of the fragment. Considering the importance of cartilage integrity, fixation of the fragment is a preferable option for a large lesion in the weight-bearing portion. Conventionally, a metal fixation device was used to fix the fragment [3]; however, use of metal devices requires reoperation for hardware removal. In recent relevant reports, bioabsorbable pins have become a principal option. Walsh et al.[6] reported the use of polyglycolic acid rods for fixation with successful outcomes in a majority of the cases. Nakamura et al.[7] reported a case with fixation of the fragment using poly-L-lactic acid (PLLA) pins. In this patient, complete healing at the osteochondral junction was accomplished as confirmed by histological examination. Although these reports showed a satisfactory outcome without procedure-related complications, postoperative complications such as foreign body reaction have been reported with the use of bioabsorbable fixation devices in the knee [8–10]. Moreover, chondral injury on the articular surface and hardware breakage have also been reported as other potential complications [14, 15]. Bone pegs have been successfully used to fix osteochondral dissecans lesions and osteochondral fractures [11–13]. This method of fixation has several advantages over other fixation methods. First, secondary surgery for hardware removal is not required. Secondly, complications such as foreign body reaction and chondral injury can be avoided. Finally, insertion of autogenous bone through the interface may biologically enhance the healing process.

In the presented case, conditions for healing were not ideal because of the 6-week time period between injury and surgery and the lack of bony attachment to the fragment. Nevertheless, satisfactory healing was attained as confirmed by the postoperative MRI and the second-look arthroscopy. The use of bone peg as a fixation device in this case may have provided a favorable environment for healing both in a biomechanical and a biological aspect. However, this is a report of only one patient without histological confirmation of healing at the osteochondral junction. Moreover, the follow-up period is still short. Accumulation of further experiences for additional cases and longer term follow-up results are required to prove the efficacy of this procedure.

Conclusions

Bone peg fixation procedure for a chondral fracture of the knee has not been reported in the previous literature. We utilized this fixation method for a patient with a large chondral fracture in the weight-bearing portion of the lateral femoral condyle. Healing at the fracture site was confirmed by MRI and second-look arthroscopy with a satisfactory functional outcome. Thus, it is thought that bone peg fixation can be a good option in surgical treatment of chondral fractures.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient’s parent for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

References

Flachsmann R, Broom ND, Hardy AE, Moltschaniwskyj G: Why is the adolescent joint particularly susceptible to osteochondral shear fracture?. Clin Orthop Rel Res. 2000, 381: 212-221.

Hopkinson WJ, Wa M, Curl WW: Chondral fractures of the knee. Cause for confusion. Am J Sports Med. 1985, 13: 309-312. 10.1177/036354658501300504.

Matthewson MH, Dandy DJ: Osteochondral fractures of the lateral femoral condyle. J Bone Joint Surg (Br). 1978, 60: 199-202.

Mashoof AA, Acholl MD, Lahav A, Greis PE, Burks RT: Osteochondral injury to the mid-lateral weight-bearing portion of the femoral condyle associated with patella dislocation. Arthroscopy. 2005, 21: 228-232. 10.1016/j.arthro.2004.09.029.

Sanders TG, Paruchuri NB, Zlatkin MB: MRI of osteochondral defects of the lateral femoral condyle: incidence and pattern of injury after transient lateral dislocation of the patella. Am J Roentgenol. 2006, 187: 1332-1337. 10.2214/AJR.05.1471.

Walsh SJ, Boyle MJ, Morganti V: Large osteochondral fractures of the lateral femoral condyle in the adolescent: outcome of bioabsorbable pin fixation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008, 90: 1473-1478. 10.2106/JBJS.G.00595.

Nakamura N, Horibe S, Iwahashi T, Kawano K, Shino K, Yoshikawa H: Healing of a chondral fragment of the knee in an adolescent after internal fixation. A case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004, 86: 2741-2746.

Barfod G, Svendsen RN: Synovitis of the knee after intraarticular fracture fixation with Biofix. Report of two cases. Acta Orthop Scand. 1992, 63: 680-681.

Takizawa T, Akizuki S, Horiuchi H, Yasuzawa Y: Foreign bony gonitis caused by a broken poly-L-lactic acid screw. Arthroscopy. 1998, 14: 329-330. 10.1016/S0749-8063(98)70151-3.

Weiler A, Hoffmann RF, Stähelin AC, Helling HJ, Sudkamp NP: Biodegradable implants in sports medicine: the biological base. Arthroscopy. 2000, 16: 305-321. 10.1016/S0749-8063(00)90055-0.

Johnson EW, McLeod TL: Osteochondral fragments of the distal end of the femur fixed with bone pegs: report of two cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1977, 59: 677-679.

Slough JA, Noto AM, Schmidt TL: Tibial cortical bone peg fixation in osteochondritis dissecans of the knee. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1991, 267: 122-127.

Victoroff BN, Marcus RE, Deutsch A: Arthroscopic bone peg fixation in the treatment of osteochondritis dissecans in the knee. Arthroscopy. 1996, 12: 506-509. 10.1016/S0749-8063(96)90052-3.

Anderson K, Marx RG, Hannafin J, Warrren RF: Chondral injury following meniscal repair with a bioabsorbable implant. Arthroscopy. 2000, 6: 749-753.

Friederichs MG, Greis PE, Burks RT: Pitfalls associated with fixation of osteochondritis dissecans fragments using bioabsorbable screws. Arthroscopy. 2001, 17: 542-545. 10.1053/jars.2001.22397.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank Mr Devin Casadey for his assistance in the preparation of the article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

HN was a major contributor in writing the manuscript. HN performed the surgery and several examinations of the patient and carried out the follow-up of the patient. SY conceived of the study, participated in its design and coordination, and helped to draft the manuscript. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Nakayama, H., Yoshiya, S. Bone peg fixation of a large chondral fragment in the weight-bearing portion of the lateral femoral condyle in an adolescent: a case report. J Med Case Reports 8, 316 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1752-1947-8-316

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1752-1947-8-316