Abstract

Introduction

Cerebral salt-wasting syndrome is a condition featuring hyponatremia and dehydration caused by head injury, operation on the brain, subarachnoid hemorrhage, brain tumor and so on. However, there are a few reports of cerebral salt-wasting syndrome caused by cerebral infarction. We describe a patient with cerebral infarction who developed cerebral salt-wasting syndrome in the course of hemorrhagic transformation.

Case presentation

A 79-year-old Japanese woman with hypertension and arrhythmia was admitted to our hospital for mild consciousness disturbance, conjugate deviation to right, left unilateral spatial neglect and left hemiparesis. Magnetic resonance imaging revealed a broad ischemic change in right middle cerebral arterial territory. She was diagnosed as cardiogenic cerebral embolism because atrial fibrillation was detected on electrocardiogram on admission. She showed hyponatremia accompanied by polyuria complicated at the same time with the development of hemorrhagic transformation on day 14 after admission. Based on her hypovolemic hyponatremia, she was evaluated as not having syndrome of inappropriate secretion of antidiuretic hormone but cerebral salt-wasting syndrome. She fortunately recovered with proper fluid replacement and electrolyte management.

Conclusions

This is a rare case of cerebral infarction and cerebral salt-wasting syndrome in the course of hemorrhagic transformation. It may be difficult to distinguish cerebral salt-wasting syndrome from syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone, however, an accurate assessment is needed to reveal the diagnosis of cerebral salt-wasting syndrome because the recommended fluid management is opposite in the two conditions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

It is not rare to encounter hyponatremia during the course of acute central nervous system (CNS) diseases. In the literature, hyponatremia complicates about 30% of subarachnoid hemorrhage cases [1, 2] and 16.8% of head injury cases [3]. Syndrome of inappropriate secretion of antidiuretic hormone (SIADH) and cerebral salt-wasting syndrome (CSWS) have been reported as the major causes of hyponatremia, while the therapeutic policy is essentially opposite because of a difference in the circulatory blood volume. Therefore, it is crucial to differentiate SIADH and CSWS from the clinical viewpoint. There have been many reports of CSWS following subarachnoid hemorrhage, but CSWS accompanying ischemic cerebrovascular diseases has been rarely reported. We report the case of a woman with cerebral infarction who developed CSWS in the course of hemorrhagic transformation.

Case presentation

A 79-year-old Japanese woman with a past medical history of hypertension and arrhythmia suddenly developed left hemiparesis and drowsy state, and was sent to our emergency room. A neurological examination showed mild consciousness disturbance, conjugate deviation to right, mild dysarthria, left unilateral spatial neglect, left facial and motor weakness, and left sensory disturbance. Magnetic resonance imaging depicted a large high intensity lesion in right middle and posterior cerebral arterial territory on diffusion weighted images, and her right internal carotid artery was obstructed on magnetic resonance arteriography (MRA). Atrial fibrillation was observed on electrocardiogram. No other vascular lesion which may have caused the disease was noted, suggesting cardiogenic cerebral embolism. Her blood analysis showed almost normal findings including hemoglobin 13.0g/dL, hematocrit 39.8%, sodium (Na) 142mEq/L, blood urea nitrogen (BUN) 16mg/dL, and creatinine, 0.69mg/dL. In addition to anti-edema therapy, the continuous intravenous infusion of heparin was initiated on the following day because no apparent hemorrhage was identified on computed tomography (CT). No marked change was noted in neurological signs, and her brain edema tended to improve on CT. On day 14, her right internal carotid artery became patent on MRA, and hemorrhage occurred in the infarct region of her right middle cerebral artery. Thus, heparin administration was discontinued on the same day.

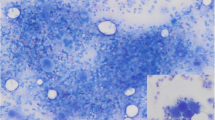

However, hemorrhage and brain edema expanded on day 15 (Figure 1), and consciousness disturbance deteriorated. Concurrently, in addition to polyuria and hyponatremia (Figure 2 and Table 1), features of dehydration appeared, such as reduction of skin turgor, collapse of the inferior vena cava (IVC), and weight loss. Fluid replacement induced only an increase of urine volume and failed to correct dehydration tendency (input of 3410mL compared to a total urinary output of 3710mL on day 20). Considering the possibility of diabetes insipidus, a water deprivation antidiuretic hormone stimulation test (by inserting 10mcg of desmopressin into a nostril by using the spray once) was performed on day 28, however, her urine volume did not decrease. Despite adequate fluid replacement, she was in negative fluid balance and her weight had decreased by 4.6%, from 39.2kg to 37.4kg. An endocrinological examination excluded SIADH because of hydration features. CSWS was assumed to be a more probable pathological state, and salt supply was added to fluid replacement on day 29. Following the alleviation of hemorrhagic transformation, her excessive urine volume slowly decreased, and her hyponatremia and dehydration improved. She was transferred to another rehabilitation hospital about 2 months after admission.

Changes of cerebral infarction in computed tomography. Slight, broad low density area in the right middle cerebral artery territory was depicted on day 1, showing the early cerebral infarction. Large low density area with midline shift and high density was depicted on day 15 and day 24, showing hemorrhagic transformation and severe brain edema.

Discussion

CSWS was reported as a condition of urine volume increase and excess loss of urinary Na accompanied by weight loss in intracranial hemorrhagic disorders [4]. Hyponatremia is a common complication in CNS diseases, especially head injury and cerebrovascular disorder, and has been regarded as SIADH in general. Considering dehydration associated with hyponatremia, however, CSWS was more common than SIADH in CNS diseases as Nelson et al. pointed out [5]. Since then, many cases of CSWS have been reported, while the pathogenesis of CSWS has remained unexplained. Some reports showed that atrial and brain natriuretic peptides (ANP and BNP) from damaged CNS tissues and abnormality of the sympathetic nervous system might induce CSWS [6–9]. That is, the increasing natriuretic peptide secretion and catecholamine might cause natriuresis via reduced renin secretion [9–12]. In our case, the level of ANP and BNP continued to be elevated (BNP 250.2pg/mL, ANP 200pg/mL) after the improvement of cardiac function.

CSWS is frequently associated with CNS hemorrhagic diseases, but only a few cases of CSWS in brain infarction have been reported [11–13]. The previous case reports of cerebral infarction had the characteristics of severe physical stress including systemic autoimmune disease, serious infection, and trauma (Table 2) [11, 13]. These systemic complications might be more susceptible to developing CSWS than localized involvement in patients with cerebral infarction. In fact, in our patient, manifestation of CSWS appeared not in the early stage but in the advanced stage with hemorrhagic transformation and excessive edema of cardiogenic brain infarction.

Whereas SIADH management requires strict fluid volume restriction, the treatment policy of CSWS is adequate fluid balance control and substitution of sodium chloride. Distinguishing these conditions may be unexpectedly difficult [14] because they show much in common; they have overlapping clinical and biochemical signs such as absence of peripheral edema, normal renal and adrenal function, low serum Na, low serum osmolality, and high urinary Na. Glycerol and mannitol as hyperosmolar agents are commonly used for brain edema, making it difficult to assess the true urinary and plasma volume. Extracellular volume assessment is a key factor to distinguish CSWS from SIADH. Due to a lack of precise assessment of the amount of extracellular fluid, it is necessary to note clinical dehydration signs such as reduction of turgor, raised heartbeat, body weight loss and collapsed IVC as well as laboratory findings including BUN/creatinine ratio. Furthermore, the persistence of hypouricemia and elevation of fractional excretion of uric acid (FEUA) even after the correction of hyponatremia may contribute to differentiate CSWS from SIADH as already reported [15]. In our patient, the serum Na level normalized on day 52, but the FEUA was still 10% higher than normal range (Table 1).

Conclusions

We reported a case of CSWS following cerebral infarction. In patients with severe stroke, disturbances of Na metabolism are frequent. It is important to investigate the causes of hyponatremia in patients with stroke, considering the differential diagnosis of SIADH and CSWS by assessing the dehydration signs.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal.

Abbreviations

- ANP:

-

Atrial natriuretic peptides

- BNP:

-

Brain natriuretic peptides

- BUN:

-

Blood urea nitrogen

- CNS:

-

Central nervous system

- CSWS:

-

Cerebral salt-wasting syndrome

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- FEUA:

-

Fractional excretion of uric acid

- IVC:

-

Inferior vena cava

- MRA:

-

Magnetic resonance arteriography

- Na:

-

Sodium

- SIADH:

-

Syndrome of inappropriate secretion of antidiuretic hormone.

References

Kurokawa Y, Uede T, Ishiguro M, Honda O, Honmou O, Kato T, Wanibuchi M: Pathogenesis of hyponatremia following subarachnoid hemorrhage due to ruptured cerebral aneurysm. Surg Neurol. 1996, 46: 500-507. 10.1016/S0090-3019(96)00034-1. discussion 507–508

Hasan D, Wijdicks EF, Vermeulen M: Hyponatremia is associated with cerebral ischemia in patients with aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Ann Neurol. 1990, 27: 106-108. 10.1002/ana.410270118.

Moro N, Katayama Y, Igarashi T, Mori T, Kawamata T, Kojima J: Hyponatremia in patients with traumatic brain injury: incidence, mechanism, and response to sodium supplementation or retention therapy with hydrocortisone. Surg Neurol. 2007, 68: 387-393. 10.1016/j.surneu.2006.11.052.

Peters JP, Welt LG, Sims EA, Orloff J, Needham J: A salt-wasting syndrome associated with cerebral disease. Trans Assoc Am Physicians. 1950, 63: 57-64.

Nelson PB, Seif SM, Maroon JC, Robinson AG: Hyponatremia in intracranial disease: perhaps not the syndrome of inappropriate secretion of antidiuretic hormone (SIADH). J Neurosurg. 1981, 55: 938-941. 10.3171/jns.1981.55.6.0938.

Palmer BF: Hyponatremia in patients with central nervous system disease: SIADH versus CSW. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2003, 14: 182-187. 10.1016/S1043-2760(03)00048-1.

Harrigan MR: Cerebral salt wasting syndrome. Crit Care Clin. 2001, 17: 125-138. 10.1016/S0749-0704(05)70155-X.

Rabinstein AA, Wijdicks EF: Hyponatremia in critically ill neurological patients. Neurologist. 2003, 9: 290-300. 10.1097/01.nrl.0000095258.07720.89.

Berendes E, Walter M, Cullen P, Prien T, Van Aken H, Horsthemke J, Schulte M, von Wild K, Scherer R: Secretion of brain natriuretic peptide in patients with aneurysmal subarachnoid haemorrhage. Lancet. 1997, 349: 245-249. 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)08093-2.

Harrigan MR: Cerebral salt wasting syndrome: a review. Neurosurgery. 1996, 38: 152-160. 10.1097/00006123-199601000-00035.

Berger TM, Kistler W, Berendes E, Raufhake C, Walter M: Hyponatremia in a pediatric stroke patient: syndrome of inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion or cerebral salt wasting?. Crit Care Med. 2002, 30: 792-795. 10.1097/00003246-200204000-00012.

Singh S, Bohn D, Carlotti AP, Cusimano M, Rutka JT, Halperin ML: Cerebral salt wasting: truths, fallacies, theories, and challenges. Crit Care Med. 2002, 30: 2575-2579. 10.1097/00003246-200211000-00028.

Loo KL, Ramachandran R, Abdullah BJ, Chow SK, Goh EM, Yeap SS: Cerebral infarction and cerebral salt wasting syndrome in a patient with tuberculous meningoencephalitis. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2003, 34: 636-640.

Oh MS, Carroll HJ: Cerebral salt-wasting syndrome. We need better proof of its existence. Nephron. 1999, 82: 110-114. 10.1159/000045385.

Maesaka JK, Fishbane S: Regulation of renal urate excretion: a critical review. Am J Kidney Dis. 1998, 32: 917-933. 10.1016/S0272-6386(98)70067-8.

Acknowledgements

No funding was obtained for this report.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

TT wrote the manuscript. TT and HU acquired patient data. HU and KM reviewed the case notes and were major contributors in writing the manuscript KN edited the manuscript and provided suggestions. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Tanaka, T., Uno, H., Miyashita, K. et al. Cerebral salt-wasting syndrome due to hemorrhagic brain infarction: a case report. J Med Case Reports 8, 259 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1752-1947-8-259

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1752-1947-8-259