Abstract

Background

Gathering of wild edible plant resources by people in sub-Saharan Africa is discussed with reference to pteridophytes, which is an ancient plant group. Pteridophytes are crucial to food diversity and security in sub-Saharan Africa, although they are notably neglected as a result of inadequate research and agricultural development. Current research and agricultural development agenda still appear to focus on the popular and commonly used food crops, vegetables and fruits; ignoring minor and underutilized plant species such as pteridophytes which have shown significant potential as sources of macro and micro nutrients required to improve the diet of children and other vulnerable groups in sub-Saharan Africa. Documentation of edible pteridophytes is needed to reveal the importance of this plant group in the region and the associated indigenous knowledge about them; so that this knowledge can be preserved and utilized species used to combat dietary deficiencies as well as improve food security in the region. The aim of this study is to present an overview of food value of pteridophytes in sub-Saharan Africa using available literature and to highlight their potential in addressing dietary deficiencies in impoverished communities in the region.

Methods

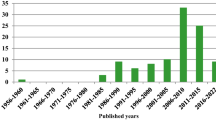

This study is based on review of the literature published in scientific journals, books, reports from national, regional and international organizations, theses, conference papers and other grey materials obtained from libraries and electronic search of Google Scholar, ISI Web of Science and Scopus.

Results

A total of 24 taxa belonging to 14 genera and 11 families are used in sub-Saharan Africa as fodder and human food. Pteridium aquilinum (L.) Kuhn is the most common edible pteridophyte in sub-Saharan Africa, used as human food in Angola, Cameroon, DRC, Gabon, Madagascar, Nigeria and South Africa, followed by Ophioglossum reticulatum L. (South Africa, Swaziland and Zanzibar), Ceratopteris thalictroides (L.) Brongn. (Madagascar and Swaziland), Diplazium sammatii (Kuhn) C.Chr. (DRC and Nigeria), Nephrolepis biserrata Sw. (DRC and Nigeria) and Ophioglossum polyphyllum A. Braun (Namibia and South Africa). The majority of edible pteridophytes are eaten as vegetables or potherbs (66.7%), with some eaten raw or as salad or edible rhizomes (12.5% each). Literature search revealed that some of the documented pteridophytes have high macro and micro nutrient content comparable to recommended FAO/WHO daily nutrient intake from conventional food crops and vegetables.

Conclusion

This study demonstrated the capability of literature research to reveal traditional knowledge on edible pteridophytes in sub-Saharan Africa from dispersed primary ethnobotanical data. Findings from this study suggest that edible pteridophytes could make an important contribution to provision of macro and micro nutrients to the sub-Saharan African population. This study also provided evidence of the importance of pteridophytes as food sources, and can therefore, used to enhance food security in the region by complementing the major food crops, vegetables and fruits.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Pteridophytes existing today represent ancient plant species which appeared about 300 million years ago in the late Devonian period [1]. Pteridophytes, often referred to as “ferns and fern allies” are vascular plants that produce neither flowers nor seeds, but reproduce and dispersed via spores. The ferns and fern allies do not form a monophyletic group [2] and pteridophyta as a taxonomic group is now regarded as made up of two classes, Lycopodiophyta (fern allies) and Pteridophyta (true ferns) [2, 3]. The Lycopodiophyta is represented by only five relict genera (Isoetes, Lycopodium, Phylloglossum, Selaginella and Stilites) [3]. The Pteridophyta are much more diverse than the Lycopodiophyta, showing great range of form and cosmopolitan in distribution [3]. Lycopodiophyta and Pteridophyta is a small group of about 12000 species [3, 4], with some species gathered in the wild for food and medicine, and others cultivated as food and ornamental plants. Gathering of wild edible plants persists in many rural communities in sub-Saharan Africa [5–10]. Local people in western Sahel region in sub-Saharan Africa, for example, have been reported to depend on a number of wild edible plants and this dependency increases during drought conditions [11]. Plants collected from the wild are used to supplement the diet of these local communities in sub-Saharan Africa which is based on rainfed cultivation of staple foods such as cassava, maize, millet, sorghum and wheat. The diversity of wild edible plants are known to offer a varied diet to rural communities [10] and wild foods are usually available at times of food shortage [7], and can be of critical importance in livelihood and survival strategies for rural households and communities.

Edible ferns are some of the most common wild food plants collected by people around the world [12–18]. The fern stems, rhizomes, leaves, young fronds and shoots and sometimes the whole plants are used for food [18]. Over time, interest in the food uses of pteridophytes has been sporadic, especially in China [17, 18], Hawaii [13, 16], Japan [19] and Nigeria [15]. Although pteridophytes continue to play an important role in the sub-Saharan Africa, there is a dearth of information on wild edible pteridophytes gathered from the wild in the region. Both surveys and in-depth ethnobotanical studies are needed to adequately record the wealth of cultural and ethnobotanical knowledge on pteridophytes held by different ethnic groups in the region. According to Pieroni [20], evaluation of plant species used in different cultural contexts is necessary in order to infer cultural components related to food acceptance and phytochemical constituents that influence the popularity of edible plants. Plant resources have gained prominence in sub-Saharan Africa as a natural asset through which communities derive food, enabling particularly poor families to achieve self-sufficiency. Documentation of use patterns of pteridophytes across sub-Saharan Africa is of relevance in understanding the importance of this ancient plant group to livelihood strategies of different ethnic groups. This is particularly important for this ancient evolutionary lineage which could potentially become extinct if harvested non-sustainably. The aim of this study is to present an overview of food value of pteridophytes in sub-Saharan Africa using available literature and to highlight their potential in addressing dietary deficiencies in impoverished communities in the region.

Research methods

Information on wild edible pteridophytes in sub-Saharan Africa was collated. Available references or reports on edible pteridophytes in sub-Saharan Africa were consulted from published scientific journals, books, reports from national, regional and international organizations, theses, conference papers and other grey materials. Literature was searched on international online databases such as ISI Web of Science, Scopus and Google Scholar using specific search terms such as “edible ferns”, “edible fern allies”, “edible pteridophytes”, “wild edible ferns”, “wild edible fern allies” and “wild edible pteridophytes”. References were also identified by searching the library collections of the University of Fort Hare, South Africa. All plant scientific names, plant families and plant authorities were verified using internet sources such as the International Plant Name Index (http://www.ipni.org), the Missouri Botanical Garden’s Tropicos Nomenclatural database (http://www.tropicos.org) and the Royal Botanic Garden and Missouri Botanic Garden plant name database (http://www.theplantlist.org). For each species, data was also collected from literature on countries in which the species are utilized, use(s), edible parts and mode of preparation of the species. Literature search was also done to document the nutritional value of pteridophytes consumed as human food in sub-Saharan Africa.

Results and discussion

Pteridophytes diversity

A total of 24 taxa belonging to 14 genera and 11 families are used in sub-Saharan Africa as fodder and human food (Table 1). Leaves of Dryopteris wallichiana (Spreng) Hyl., Nephrolepis biserrata (Sw.) Schott and Ophioglossum grande L. are used as fodder for goats, sheep and other small ruminants in Nigeria [15, 21], while the rest of the species are used as human food. All reported species are indigenous to the region, with Pteridium aquilinum (L.) Kuhn as the most widespread fern, occurring mainly as a cosmopolitan weed with an almost worldwide distribution apart from mountainous, desert and arctic areas [22]. Plant families with the highest number of food plants are Ophioglossaceae, represented by seven species, followed by Athyraceae represented by three species; and Davalliaceae, Dennsteadtiaceae, Marsileaceae, Pteridaceae and Thelypteridaceae represented by two species each. Athyraceae, Dennsteadtiaceae, Ophioglossaceae, Pteridaceae and Thelypteridaceae are among the most species-rich pteridophyte families, represented by at least 80 species [2, 23]. The rest of the families are represented by one species each, as shown in Table 1. The genera with highest number of species are Ophioglossum represented by six species, followed by Diplazium represented by three species; and Ceratopteris, Marsilea and Nephrolepsis represented by two species each. Ceratopteris, Diplazium, Marsilea, Nephrolepsis and Ophioglossum have the highest diversity of species probably because these are large genera worldwide, characterized by at least five species each [23].

Edible pteridophytes have been recorded from east, central, south and west Africa (Figure 1). Most of the ethnobotanical data on edible pteridophytes have been reported in DRC and Nigeria (Table 1). In Nigeria, seven species: Botrychium lanuginosum Wall. ex Hook et Grev, Diplazium esculentum (Retz.) Sw., Diplazium sammatii (Kuhn) C.Chr., Nephrolepis cordifolia (L.) Presl., Ophioglossum vulgatum L. and Pteridium aquilinum (L.) Kuhn are utilized as human food [15, 30, 38]. Seven edible taxa have been reported in DRC, which include Blotiella glabra (Bory) R.M.Tryon, Christella dentata (Forssk.) Brownsey & Jermy, Cyathea manniana Hook., Diplazium sammatii, Lomariopsis sp., Nephrolepis biserrata (Sw.) Schott and Pteridium aquilinum[24, 37]; and five species among them, Ceratopteris thalictroides (L.) Brongn., Diplazium proliferum (Lam.) Thouars, Ophioglossum ovatum Bory, Pteridium aquilinum and Stenochlaena tenuifolia (Desv.) T. Moore have been reported in Madagascar [26, 29, 32, 40]. Three edible species have been reported in South Africa, which include Ophioglossum polyphyllum A. Braun [6, 34], Ophioglossum reticulatum L. [35] and Pteridium aquilinum[39]. Three edible species have been reported in Swaziland, which include Ceratopteris thalictroides, Ophioglossum lusoafricanum Prantl and Ophioglossum reticulatum[27]. Cyclosorus gongylodes (Schkuhr) Link and Marsilea minuta L., are the only two edible species reported in Gambia [28, 31], Pteridium aquilinum reported in Angola, Cameroon and Gabon [32], Ceratopteris cornuta (P. Beauv.) Lepr. reported in Liberia [14, 25], Ophioglossum polyphyllum A. Braun reported in Namibia [33], Marsilea minuta L. reported in Senegal [31] and Ophioglossum reticulatum reported in Zanzibar [36].Pteridophytes occur throughout sub-Saharan Africa, particularly in rainforests and afromontane forests of east, central, south and west Africa, making the plant group effective and reliable source of human food. However, due to lack of direct evidence for pteridophyte use from other countries, particularly in north and central Africa, the importance of pteridophytes can only be inferred from ethnobotanical studies done in Angola, Cameroon, DRC, Gabon, Gambia, Liberia, Madagascar, Namibia, Nigeria, Senegal, South Africa, Swaziland and Zanzibar (Figure 1). Although findings from these countries about edible pteridophytes are diverse in terms of utilized species, the findings may not apply directly to all countries in the sub-Saharan African region. It is clear that more detailed national level studies should be undertaken, particularly in north and central Africa where documentation on pteridophyte use is scanty or missing.

Pteridophytes collection and parts consumed

Pteridium aquilinum is the most widely used pteridophyte as a source of human food (Figure 2). It is used as food in Angola, Cameroon, DRC, Gabon, Madagascar, Nigeria and South Africa. Ophioglossum reticulatum is utilised as human food in eastern and southern Africa, that is, in South Africa, Swaziland and Zanzibar (Figure 2). Ceratopteris thalictroides is used as human food in Madagascar and Swaziland, Diplazium sammatii is utilized as human food in DRC and Nigeria; and Ophioglossum polyphyllum is used as human food in Namibia and South Africa (both countries in southern Africa) (Figure 2). Despite its worldwide distribution, the range of basic applications of Pteridium aquilinum are similar across its range of distribution, and it is mainly used as a food source [22]. In Japan and Korea, young shoots of Pteridium aquilinum are an important dietary element [22, 41]. The shoots are soaked for a day in water and ashes, then steamed or boiled and eaten as a vegetable or soup [41]. Research by Liu et al. [18] revealed that the leaves and rhizomes of Pteridium aquilinum are consumed by billions of people in the world. The same authors argued that Pteridium aquilinum is part of the diet of many poor people in south Pacific islands to northern and temperate prairies because of its wide distribution and easy accessibility. Ophioglossum are widely eaten in Asia, with Ophioglossum reticulatum used as a vegetable in India and Indonesia [17], while Ophioglossum polyphyllum is consumed as a vegetable in south central Tibet [17]. Research by the same authors, revealed that Ophioglossum polyphyllum is eaten in summer as a vegetable but also dried and stored for later consumption in winter. Ceratopteris thalictroides is commonly eaten throughout south east Asia, for example, in Malaysia and Japan where it is an established luxury vegetable [26]. According to Bassey et al. [30], various parts of Diplazium sammatii are consumed by various people throughout the world. The same authors argued that Diplazium sammatii is not an emergency or primitive food type. This assertion by Bassey et al. [30] correlates strongly with observations made by Pieroni [41] that eating food from the wild is not simply an essential response in times of famine or food shortages or an easy way to obtain primary nutrients, but more often a complex evolutionary process involving different aspects of the relationship between humans and their natural environment.

Young leaves or enrolled fronds, often referred to as crosiers or fiddleheads are the primary pteridophyte food sources in sub-Saharan Africa (70.8%*), followed by leaves (50%*) and rhizomes (16.7%*) (Table 1). (*Some plant parts are reported in more than one plant part category). The majority of pteridophytes are eaten as vegetables or potherbs (66.7%), followed by leaves cooked as leafy vegetables (45.8%), leaves cooked as condiment, leaves eaten raw or as salad, edible rhizomes and leaves fed to livestock (12.5% each), herbal tea and famine food (4.2% each) (Figure 3). When a rhizome is eaten, leaf bases are removed, cleaned and peeled. Pteridophytes consumed as leafy vegetables or potherbs or salads, are usually collected at vegetative stage, when leaves are young and tender. These findings correlates with observations made by Lognay et al. [17] that bundles of freshly uncurled fronds are a common site in the rural markets of the Philippines, Indonesia, Malaysia and New Guinea.

Suitability of pteridophytes as food sources

Some pteridophytes used as food sources in sub-Saharan Africa, for example, Diplazium esculentum[42], Diplazium sammatii[30], Nephrolepis biserrata[43, 44], Nephrolepis cordifolia[21] and Ophioglossum polyphyllum[17], have high nutritional value in comparison to the FAO/WHO nutrient standards [45] (see Table 2). These five edible pteridophytes are important sources of macro and micro nutrients which are important for the maintenance of good health and prevention of diseases. The calorific value of 408.5 kcal kg-1 for Diplazium sammatii and 3413 kcal kg-1 for Diplazium esculentum (Table 2), compare favourably to 210–1340 kcal kg-1 reported for common vegetables (broad beans, cabbage, cauliflower, lettuce, spinach) and common fruits (apple, lichi, mango, pawpaw) reported by Seal [42]. The carbohydrate and protein content of the edible pteridophytes shown in Table 2 is also higher than the carbohydrate and protein content of common vegetables and fruits obtained by Seal [42]. All the five edible pteridophytes have high levels of minerals in comparison to mineral content of common food crops, vegetables and fruits available in the published literature. For example, copper and zinc content of the edible pteridophytes shown in Table 2 is higher than the copper and zinc content of common vegetables and fruits obtained by Seal [42]. Therefore, pteridophytes are an important source of macro and micro nutrients and may be consumed by local communities to enhance nutrient intake or diversify the diet of local communities in sub-Saharan Africa.

Pteridophytes can also play an important role to food security in sub-Saharan Africa, can be utilized during drought periods when few crops are available and their year round availability increases their value as an important food plant group. The data documented in this study can be used in determining which pteridophytes can be preferentially utilized to benefit the overall nutrition of communities who inhabit sub-Saharan Africa. There is uniformity in the use of edible pteridophytes in sub-Saharan Africa, regardless of cultural differences in aspects such as language, history and social organization in general (Table 1, Figure 1). Based on the current baseline study, there is need to do further studies in other countries in the African continent aimed at documenting pteridophytes diversity used as food which at the present appear to be more or less homogenous. The observed similarities in pteridophytes use by different ethnic and cultural groups provide an insight into the possibility that regional groups may have been more closely linked in the past. It is probable that pteridophytes were widely consumed by the pastoralists and hunter-gatherers, historically referred to as the bushmen in sub-Saharan Africa. The oral transmission of traditional knowledge on the uses of pteridophytes by indigenous people has largely been eroded over the centuries due to land fragmentation, migration and improved agricultural activities in favour of improved food crops, vegetables and fruits. Detailed studies across national boundaries are also important in order to find out the possible reasons for similarities in pteridophyte uses. Traditional and cultural knowledge about pteridophytes use should vary, as this indigenous knowledge is not formalized. Detailed comparison of pteridophyte use by different ethnic groups will provide us with a clue to understanding pteridophytes use history, cultural diversity and variations of cultural practices of these ethnic groups.

Conclusion

This study examined edible pteridophytes, some of them widely distributed in sub-Saharan Africa but whose economic value have not been fully explored. Local people in sub-Saharan Africa use different pteridophytes species as food. Interest in expanding the use of minor and underutilized plant resources such as pteridophytes has been sporadic, especially in rural development initiatives. The uses of pteridophytes outlined in this study including the nutritional information of some of the edible pteridophytes underscore the untapped potential of pteridophytes in meeting basic human needs. An effort should be made to initiate and harness the synergetic relationships that exist between pteridophytes uses and indigenous knowledge of people in sub-Saharan Africa, passed on from generation to generation. This review also demonstrated the capability of literature research to reveal indigenous knowledge by researching and compiling information from the growing body of dispersed primary ethnobotanical data. The core challenge that confronts sub-Saharan Africa is the promotion of edible pteridophytes as an alternative means of addressing and combating dietary deficiencies, thereby improving food security in the region.

Author’s contribution

AM conceptualized the study and wrote the manuscript. The author read and approved the final manuscript.

References

Fernández H, Kumar A, Revilla MA: Working with ferns: issues and applications. 2011, New York: Springer

Smith AR, Pryer KM, Schuettpelz E, Korall P, Schneider H, Wolf PG: A classification for extant ferns. Taxon. 2006, 55: 705-731. 10.2307/25065646.

World Conservation Monitoring Centre (WCMC): Global biodiversity: status of the earth's living resources. 1992, London: Chapman and Hall

Chapman AD: Numbers of living species in Australia and the world. 2009, Canberra: Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts

Ogle BM, Grivetti LE: Legacy of the chameleon edible plants in the Kingdom of Swaziland, South Africa: A cultural, ecological, nutritional study. Parts II–IV, species availability and dietary use, analysis by ecological zone. Ecol ood Nutr. 1985, 17: 1-30. 10.1080/03670244.1985.9990879.

Cunningham AB: Collection of wild plant foods in tembe thonga society: a guide to iron age gathering activities. Ann Natal Mus. 1988, 29: 433-446.

Harris FMA, Mohammed S: Relying on nature: wild foods in northern Nigeria. Ambio. 2003, 32: 24-29.

Ogoye-Ndegwa C, Aagaard-Hansen J: Traditional gathering of wild vegetables among the Luo of western Kenya: a nutritional anthropology project. Ecol ood Nutr. 2003, 42: 69-89. 10.1080/03670240303114.

Balemie K, Kebebew F: Ethnobotanical study of wild edible plants in derashe and kucha districts, south Ethiopia. J Ethnobiol Ethnomed. 2006, 2: 53-10.1186/1746-4269-2-53.

Maroyi A: The gathering and consumption of wild edible plants in nhema communal area, midlands province, Zimbabwe. Ecol ood Nutr. 2011, 50: 506-525. 10.1080/03670244.2011.620879.

Cook JA, Vanderjagt DJ, Pastuszyn A, Mounkaila G, Glew RS, Millson M, Glew RH: Nutrient and chemical composition of 13 wild plant foods of niger. J Food Compos Anal. 2000, 13: 83-92. 10.1006/jfca.1999.0843.

Copela EB: Edible ferns. Am Fern J. 1942, 32: 121-126. 10.2307/1545216.

Fosberg FR: Uses of Hawaiian ferns. Am Fern J. 1942, 32: 15-23. 10.2307/1544977.

May LW: The economic uses and associated folklore of ferns and fern allies. Bot Rev. 1978, 44: 491-528. 10.1007/BF02860848.

Nwosu MO: Ethnobotanical studies on some pteridophytes of southern Nigeria. Econ Bot. 2002, 56: 255-259. 10.1663/0013-0001(2002)056[0255:ESOSPO]2.0.CO;2.

Leach H: Fern consumption in Aotearoa and its oceanic precedents. J Polynesian Soc. 2003, 112: 141-156.

Lognay G, Haubruge E, Delcarte E, Wathelet B, Mathieu F, Marlier M, Malaisse F: Ophioglossum polyphyllum A. Braun in Seub. (Ophioglossaceae, Pteridophyta), a rare potherb in south central Tibet (T. A. R., P. R. China). Geo Eco Trop. 2008, 32: 9-16.

Liu Y, Wujisguleng W, Long C: Food uses of ferns in china: a review. Acta Soc Bot Pol. 2012, 81: 263-270. 10.5586/asbp.2012.046.

Hodge WH: Fern foods of Japan and the problem of toxicity. Am Fern J. 1973, 63: 77-80. 10.2307/1546182.

Pieroni A: Evaluation of the cultural significance of wild food botanicals traditionally consumed in northwestern Tuscanty, Italy. J Ethnobiol. 2001, 21: 89-104.

Oloyede FA, Ajayi OS, Bolaji IO, Famudehin TT: An assessment of biochemical, phytochemical and antinutritional compositions of a tropical fern: Nephrolepis cordifolia L. Life J Sci. 2013, 15: 645-651.

Madeja J, Harmata K, Kolaczek P, Karpinska-Kolaczek M, Platek K, Naks P: Bracken fern (Pteridium aquilinum L. Kuhn), Mistletoe (Viscum album L.), and bladdernut (Staphylea pinnata L.): Mysterious plants with unusual applications. Plants and culture: Seeds of the cultural, heritage of Europe. Edited by: Morel J-P, Mercuri AM. 2009, Edipuglia: Centro Universitario Europeo, 207-215.

Annon: Ferns and fern allies: pteridophytes. 2014, http://www.theplantlist.org,

Termote C, van Damme P, Djailo BD: Eating from the wild: Turumbu, Mbole and Bali traditional knowledge on noncultivated edible plants, Tshopo District, DRC. Genet Res Crop Evol. 2011, 58: 585-618. 10.1007/s10722-010-9602-4.

Hartley WT: Handbook of Liberian ferns. 1957, Wakefield: Murray Press

van der Burg WJ: Ceratopteris thalictroides (L.) Brongn. Plant resources of tropical Africa 2. vegetables. Edited by: Grubben GJH, Denton OA. 2004, Leiden: PROTA Foundation, 173-175.

Long C: Swaziland’s flora: siSwati names and uses. 2005, http://www.sntc.org.sz/flora/clbotalpha.asp?l=C&pg=10,

Burkill HM: The useful plants of west tropical Africa 5. 1985, Richmond: Royal Botanic Gardens

van der Burg WJ: Diplazium proliferum (Lam.) Thouars. Plant resources of tropical Africa 2. vegetables. Edited by: Grubben GJH, Denton OA. 2004, Leiden: PROTA Foundation, 288-289.

Bassey ME, Etuk EUI, Ibe MM, Ndon BA: Diplazium sammatii: Athyraceae ('Nyama idim'): age-related nutritional and antinutritional analysis. Plant Foods Hum Nutr. 2001, 56: 7-12. 10.1023/A:1008185513685.

van der Burg WJ: Marsilea minuta L. Plant resources of tropical Africa 2. vegetables. Edited by: Grubben GJH, Denton OA. 2004, Leiden: PROTA Foundation, 379-380.

van der Burg WJ: Pteridium aquilinum (L.) Kuhn. Plant resources of tropical Africa 2. vegetables. Edited by: Grubben GJH, Denton OA. 2004, Leiden: PROTA Foundation, 439-441.

Malaisse F, Lognay G, Haubruge E, de Kesel A, Delcarte E, Wathelet B, van Damme P, Begaux F, Chasseur C, Drolkar P, Goyens P, Hinsenkamp M, Leteinturier B, Mathieu F, Rinchen L, van Marsenille C, Wangdu L, Wangla R: The alternative food path or the very little diversified diet hypothesis. Big bone disease: A multidisciplinary approach of kashin-beck disease in Tibet autonomous region (P.R. China). Edited by: Malaisse F, Mathieu F. 2008, Gembloux: les presses agronomiques de Gembloux, 105-130.

Ntuli NR, Zobolo AM, Siebert SJ, Madakadze RM: Traditional vegetables of northern KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa: Has indigenous knowledge expanded the menu?. Afr J Agric Res. 2012, 7: 6027-6034.

Murray JS: The production of food to supplement natural foods in the Bantu areas. S Afr Med J. 1964, 22: 628-629.

van der Burg WJ: Ophioglossum reticulatum L. Plant resources of tropical Africa 2. vegetables. Edited by: Grubben GJH, Denton OA. 2004, Leiden: PROTA Foundation, 404-405.

Termote C, van Damme P, Djailo BD: Eating from the wild: turumbu indigenous knowledge on noncultivated edible plants, tshopo district, DRC. Ecol Food Nutr. 2010, 49: 173-207. 10.1080/03670241003766030.

Nwiloh BI, Monago CC, Uwakwe AA: Chemical composition of essential oil from the fiddleheads of Pteridium aquilinum L. Kuhn found in Ogoni. J Med Plants Res. 2014, 8: 77-80. 10.5897/JMPR2013.5093.

Roberts M: Indigenous healing plants. 1990, Cape Town: Southern Book Publishers, Halfway House

van der Burg WJ: Stenochlaena tenuifolia (Desv.) T.Moore. Plant resources of tropical Africa 2. vegetables. Edited by: Grubben GJH, Denton OA. 2004, Leiden: PROTA Foundation, 515-516.

Pieroni A: Gathering food from wild. The cultural history of plants. Edited by: Prance G, Nesbit M. 2005, London: Routledge, 29-44.

Seal T: Evaluation of nutritional potential of wild edible plants, traditionally used by the tribal people of Meghalaya state in India. Am J Plant Nutr Fertil Technol. 2013, 2: 19-26.

Oloyede FA, Alafe BO, Oloyede FM: Nutrient evaluation of Nephrolepis biserrata (Nephrolepidaceae, Pteridophyta). Bot Lith. 2008, 14: 207-210.

Essuman EK: Protein extraction from fern and its physicochemical properties. MSc Thesis. 2013, Kumasi: Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology

FAO/WHO: Codex alimentarius commission: food additives and contaminants. 2001, Rome: Joint FAO/WHO Food standards programme, 1-289. ALINORM 01 /12A

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to two anonymous reviewers for constructive comments on earlier drafts of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The author declares that he has no competing interests.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Maroyi, A. Not just minor wild edible forest products: consumption of pteridophytes in sub-Saharan Africa. J Ethnobiology Ethnomedicine 10, 78 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1746-4269-10-78

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1746-4269-10-78