Abstract

Background

Chronic painful conditions have an important influence on the ability to work. Work-related outcomes, however, are not commonly reported in publications on trials investigating the treatment of chronic painful conditions. We aim to provide an overview of the reporting of work-related outcomes in such trials and investigate the relationship between work-related outcomes and pain outcomes.

Methods

We conducted a systematic literature search in PubMed with the aim of identifying randomised placebo-controlled clinical trials investigating treatments for chronic painful conditions or rheumatic diseases that also reported on work-related outcomes. Methodological study quality was assessed with the Oxford Quality Scale (OQS). Meta-analyses were conducted for the outcomes of interference with work and number of patients with at least 30% reduction in pain intensity (30% pain responders). The correlation between work-related and pain outcomes was investigated with regression analyses.

Results

We included 31 publications reporting on 27 datasets from randomised placebo-controlled trials (with a total of 11,434 study participants) conducted in chronic painful or rheumatic diseases and reporting on work-related outcomes. These 31 publications make up only about 0.2% of all publications on randomised placebo-controlled trials in such conditions. The methodological quality of the included studies was high; only nine studies scored less than four (out of a maximum five) points on the OQS. Sixteen different work-related outcomes were reported on in the studies. Of 25 studies testing for the statistical significance of changes in work-related outcomes over the course of the trials, 14 (56%) reported a significant improvement; the others reported non-significant changes. Eight studies reported data on both interference with work and 30% pain responders: meta-analyses demonstrated similar, statistically significant improvements in both these outcomes with active therapy compared to placebo and regression analysis showed that these outcomes were correlated.

Conclusions

Despite the importance of pain as a reason for decreased ability to work, work-related outcomes are reported in substantially less than 1% of publications on placebo-controlled trials in chronic painful and rheumatic diseases. Work-related outcomes and pain responder outcomes are closely related.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Chronic painful conditions are very common as a recent systematic review of prevalence studies has demonstrated [1]. For example, a large survey found that about one fifth of European adults suffered from pain of at least six months’ duration and a third of those pain sufferers had severe pain [2]. Patients affected by a chronic painful disease experience the adverse effects of their condition on a number of domains of life, including work. In different studies 13% to 76% of chronic pain patients experienced loss of employment or were unable to undertake employment [1]. Those with moderate and, especially, severe pain are particularly affected [3]. Targeting inability to work and interference with work due to chronic pain therefore is important both from an individual as well as a societal, economic, perspective. It would be informative to know how work ability is affected by common pain treatments.

However, work-related outcomes are not commonly reported in publications on randomised controlled trials investigating the treatment of chronic painful conditions or rheumatic diseases (where pain typically is a prominent symptom). Where such data have been analysed, there is good evidence that those patients experiencing substantial improvements in pain outcomes in the context of clinical trials also experience a substantial improvement in their ability to work [4]. The question is how generalisable this agreement between work-related and pain-related study outcomes is.

With this publication we aim to, firstly, provide an overview of the reporting of work-related outcomes in chronic pain trials and, secondly, investigate the relationship between work-related outcomes and pain-related outcomes across different studies. Because for pain intensity the reporting as ‘responder outcomes’, such as the proportion of study participants experiencing at least 30%, or 50%, reduction in pain intensity over the course of a trial (30% or 50% pain responders), is more informative than treatment group average data, we focus on pain responder outcomes; this is in agreement with recent guidance on performing systematic reviews in the chronic pain field [5].

Methods

Literature search, study quality assessment, and data extraction

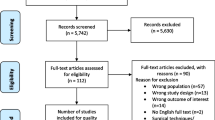

We conducted a systematic literature search in Medline (PubMed) with the aim of identifying randomised controlled clinical trials investigating treatments for chronic painful conditions or rheumatic diseases that reported on any work-related study outcomes. We limited ourselves to placebo-controlled (or sham-controlled) studies to ensure some basic comparability between the studies and to be able to compare active treatments vs. placebo for work-related and pain-related study outcomes.Our search strategy is shown in Figure 1 and included search terms to identify work-related outcomes, search terms to identify chronic painful conditions or rheumatic diseases, and search terms to identify placebo or sham controlled studies. We did not activate any filters in PubMed but limited ourselves to articles published as full papers in English or German. The date of the last search was 13 June 2013. To estimate the total number of publications that could potentially have reported on work-related outcomes, we also performed our search without the work-related terms.

For inclusion in our systematic review studies needed to be single or double blind, use a placebo or sham control, include patients suffering from chronic pain (of at least 3 months’ duration) or with a rheumatic disease, and report on any work-related outcomes. We anticipated that a variety of work-related measures would be reported in the studies. In order to be inclusive we accepted any outcome measure that specifically addresses work or any aspect of work and were work-related effects were reported separately (i.e. not only as a summary score covering work and other domains of life). Studies investigating children or experimentally induced pain were excluded.

We assessed the methodological study quality with the Oxford Quality Scale, a standard and very widely used instrument for evaluating clinical trials that assesses the domains of randomisation, blinding and withdrawals/dropouts, and grades study quality on a scale of zero to five points [6].

Data were extracted on the publication details, the conditions studied, the treatments investigated, study size and duration, as well as work-related and pain-related study outcomes.

Data analysis

We assessed means (and standard deviations [SDs]) of differences in work-related outcomes between trial beginning and end. If a study did not report SDs for mean differences between baseline and end of study values, SDs were estimated from p-values from hypothesis tests on the baseline to trial end differences. Studies reporting medians and interquartile ranges only had their data transformed to means and SDs by assuming the median to be the mean and the interquartile range to be 1.35 SDs.

Meta-analysis of data was performed with Review Manager (RevMan) [7]. Meta-analyses were conducted for the outcomes of ‘interference with work’ and 30% pain responders. Data for ‘interference with work’ were from component questions of the Brief Pain Inventory (question on pain interfering with normal work, including both work outside the home and housework), the Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire (question on how much pain or other symptoms of fibromyalgia interfered with the ability to do work, including housework) and the Sheehan Disability Scale (question on how much the symptoms have disrupted work or school work). These three questions were all assessed on scales of 0–10 points.

For meta-analyses the random effects model was used. If the between study heterogeneity was estimated to be zero (i.e. I2 = 0), the analysis is equivalent to a fixed effect meta-analysis.

The relationships between the outcomes of interference with work and 30%, or 50%, pain responders were investigated with regression analyses.

A further regression analysis was conducted for work-related and pain-related outcomes expressed as mean differences. In order to utilise all available data, which were expressed as different outcomes, we standardised the mean differences of the work-related and pain-related endpoints, as described by Hedges [8], before performing linear regression analysis.

All regression analyses were conducted in R [9]. The weights for the included studies were assigned according to the inverse variances of their work-related endpoints.

Results

Reporting of work-related outcomes

Our systematic literature search (Figure 2) yielded 1063 potentially relevant hits of which 948 were excluded as not relevant on the basis of study titles and abstracts. One hundred and fifteen remaining articles and one additional study from the references of a meta-analysis were examined as full texts. Eighty five of these full texts needed to be excluded. Additional file 1 details the excluded studies with reasons for their exclusion.

We identified as suitable for inclusion in our systematic review 31 publications [4, 10–39] reporting on 27 datasets from randomised placebo-controlled trials in chronic painful diseases or rheumatic diseases (Table 1). Typically such a dataset corresponds to data from one clinical trial. Arnold et al. [12] and Bradley et al. [18] are meta-analyses that incorporated the same four clinical trials [11, 20, 40, 41]. Two of these published work-related data [11, 20]. In order to avoid counting the same patients more than once, all these studies were treated as one dataset. Bennett et al. [16] and Bennett et al. [17] were also treated as one dataset, because they both reported on the same trial. Furthermore, Straube et al. [4] reported an individual patient meta-analysis of work-related data from four trials but was counted as one dataset because the work-related data had not been published separately for those trials.

The 31 publications reporting on work-related outcomes comprised only 0.23% of all publications on randomised placebo-controlled trials in chronic painful or rheumatic conditions (13,754 hits when searching as in Figure 1 but without the work-related search terms). The 31 studies that reported on work-related outcomes included a total of 11,434 patients (mean ages in the studies ranged from 34 to 63 years; overall 76% of patients were women). Among the 31 studies, the reporting of work-related outcomes was diverse: 16 different work-related outcomes were reported on (Table 1). The methodological study quality was generally high; only nine studies scored less than four (out of a maximum five) points on the OQS (Table 1).

Of 25 studies testing for the statistical significance of changes in work-related outcomes over the course of the trials, 14 (56%) reported a significant improvement; the others reported non-significant changes (Table 2).

Relationship between work and pain outcomes

We wanted to examine the relationship between work-related outcomes and pain-related outcomes. As elaborated above we primarily used responder outcomes for pain intensity and as regards work-related outcomes we used the outcome of ‘interference with work’ as estimated from the answers to similar questions about interference with work (or disruption of work) from three commonly used questionnaires. There were eight studies [4, 12, 21, 22, 32, 34–36] that reported data on both interference with work and 30% pain responders; these studies were included in meta-analyses for the outcomes of interference with work (Figure 3) and 30% pain responders (Figure 4). For Straube et al. [4] data about pain responders was taken from Straube et al. [42].

These meta-analyses demonstrated statistically significant improvements in both outcomes with active therapy compared to placebo and also demonstrated that both outcomes behaved in a roughly similar manner, in individual studies and overall.

To assess the degree of similarity between these outcomes formally, we performed regression analyses (Figure 5); these showed that the outcomes were significantly correlated when the 30% responder rates were expressed as risk differences (p = 0.012) as well as when they were expressed as risk ratios (p = 0.015). For the 50% responder rates we found a significant correlation when the responder rates were expressed as risk ratios (p = 0.038), but significance was narrowly missed when they were expressed as risk differences (p = 0.053). As the study of Skljarevski et al. [34] did not report 50% pain responder rates, it did not contribute to those analyses.

Regression analysis. Regression analysis of the improvement in interference with work from study beginning to end and ‘30% pain responders’, expressed as risk ratios [RR, red colour] or risk differences [RD, blue colour]. Interference with work was measured on a scale of 0–10 points. The size of the symbols represents the weights of the individual studies in the regression analysis (inverse variance). Regression lines are solid; broken lines mark the 95% confidence intervals.

Nine studies reported mean differences of different pain-related and work-related outcomes. Six trials assessed interference with work and pain severity with questions from the Brief Pain Inventory [21, 22, 32, 34–36]. Arnold et al. [12] reported data on disruption of work from the Sheehan Disability Scale and data on pain from the Brief Pain Inventory. Two studies used visual analogue scales to evaluate productivity at work and pain [26, 39]. The data for the pain-related outcomes for these two studies, Kavanaugh et al. [26] and van der Heijde et al. [39], were taken from Antoni et al. [43] and van der Heijde et al. [44]. Because of the multiple outcomes reported across the papers we standardised the reported mean differences before performing linear regression. Again, a statistically significant correlation emerged (p = 0.035).

Discussion

We were able to confirm our impression that work-related outcomes are indeed reported only very infrequently in chronic pain and rheumatology trials. This is somewhat surprising, given the importance of pain as a reason for decreased ability to work and given that a number of questionnaires that are commonly used in pain and rheumatology trials contain component questions addressing work-related outcomes [4]. The problem very likely is not one of the collection of work-related data but of the reporting of such data in publications.

This means two things. Firstly, that raising awareness of the importance of work-related outcomes among people and institutions involved in conducting trials in chronic pain and rheumatology is worthwhile and may lead to such data being reported more commonly for future trials and, secondly, that re-analysis of existing datasets could be informative, as long as access to work-related data can be obtained, preferably at the level of the individual patient.

Some limitations of our analysis need to be discussed: we based our systematic review on searching only one database and were limited (due to the linguistic skills of the authors, or lack thereof) to papers published in English or German. It is quite possible that we missed relevant studies published in journals not indexed in Medline, published in languages other than English or German, or published after our search had closed. We do not claim, therefore, to have identified all placebo-controlled trials conducted in chronic pain or rheumatologic diseases and reporting on work related outcomes. What we have, however, should be a fairly good and representative sample, including important trials published recently and in high impact journals.

We have confidence in our conclusion, therefore, that work-related outcomes are indeed reported very infrequently in journal publications resulting from chronic pain and rheumatology trials.

Chronic pain significantly interferes with work. A recent large systematic review of observational studies demonstrated the negative impact of chronic pain on work related outcomes [45]. It is therefore logical to suspect that pain relief will be associated with an improvement in the ability to work. Based on the evidence included in our systematic review (eight studies, with 5726 participants, conducted in fibromyalgia, back pain and osteoarthritis, investigating as treatments duloxetine, pregabalin, and oxicodone, and lasting eight to 28 weeks) we conclude that the outcome of improvement in interference with work is indeed closely related to the outcome of attaining at least 30% reduction in pain intensity over the course of the studies. Future work, in other painful conditions and assessing different treatments, needs to assess how robust this relationship is and whether pain-related outcomes (such as 30% pain responders) can perhaps be used to estimate interference with work. If they can, then this would open the door to using pain responder outcomes for evaluations of the impact of pain treatments also on work ability, which might be an important consideration for the assessment of pain treatments.

Conclusions

Firstly, work-related outcomes are reported very infrequently, in substantially less than 1% of the publications we identified in our search for placebo-controlled trials in chronic painful and rheumatic diseases.

Secondly, work-related outcomes and pain responder outcomes are closely related. Future studies, perhaps based on individual patient analyses and meta-analyses of existing datasets, should address whether pain responder outcomes can be used to assess ability to work.

References

Moore RA, Derry S, Taylor RS, Straube S, Phillips CJ: The costs and consequences of adequately managed chronic non-cancer pain and chronic neuropathic pain. Pain Pract 2014, 14: 79–94.

Breivik H, Collett B, Ventafridda V, Cohen R, Gallacher D: Survey of chronic pain in Europe: prevalence, impact on daily life, and treatment. Eur J Pain 2006, 10: 287–333.

Langley P, Müller-Schwefe G, Nicolaou A, Liedgens H, Pergolizzi J, Varrassi G: The impact of pain on labor force participation, absenteeism and presenteeism in the European Union. J Med Econ 2010, 13: 662–672.

Straube S, Moore RA, Paine J, Derry S, Phillips CJ, Hallier E, McQuay HJ: Interference with work in fibromyalgia: effect of treatment with pregabalin and relation to pain response. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2011, 12: 125.

Moore RA, Eccleston C, Derry S, Wiffen P, Bell RF, Straube S, McQuay H, ACTINPAIN Writing Group of the IASP Special Interest Group on Systematic Reviews in Pain Relief; Cochrane Pain, Palliative and Supportive Care Systematic Review Group Editors: “Evidence” in chronic pain–establishing best practice in the reporting of systematic review. Pain 2010, 150: 386–389.

Jadad AR, Moore RA, Carroll D, Jenkinson C, Reynolds DJ, Gavaghan DJ, McQuay HJ: Assessing the quality of reports of randomized clinical trials: is blinding necessary? Control Clin Trials 1996, 17: 1–12.

Review Manager (RevMan) [Computer program]. Version 5.2. Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration; 2012.

Hedges LV: Distribution theory for glass’s estimator of effect size and related estimators. J Educ Behav Stat 1981, 6: 107–128.

R: A language and environment for statistical computing: Version 3.0.3. The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, R Core Team. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2014. URL http://www.R-project.org/

Albert HB, Sorensen JS, Christensen BS, Manniche C: Antibiotic treatment in patients with chronic low back pain and vertebral bone edema (Modic type 1 changes): a double-blind randomized clinical controlled trial of efficacy. Eur Spine J 2013, 22: 697–707.

Arnold LM, Rosen A, Pritchett YL, D’Souza DN, Goldstein DJ, Iyengar S, Wernicke JF: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of duloxetine in the treatment of women with fibromyalgia with or without major depressive disorder. Pain 2005,2005(119):5–15.

Arnold LM, Clauw DJ, Wohlreich MM, Wang F, Ahl J, Gaynor PJ, Chappell AS: Efficacy of duloxetine in patients with fibromyalgia: pooled analysis of 4 placebo-controlled clinical trials. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry 2009, 11: 237–244.

Barkham N, Coates LC, Keen H, Hensor E, Fraser A, Redmond A, Cawkwell L, Emery P: Double-blind placebo-controlled trial of etanercept in the prevention of work disability in ankylosing spondylitis. Ann Rheum Dis 2010, 69: 1926–1928.

Baron R, Freynhagen R, Tölle TR, Cloutier C, Leon T, Murphy TK, Phillips K, A0081007 investigators: The efficacy and safety of pregabalin in the treatment of neuropathic pain associated with chronic lumbosacral radiculopathy. Pain 2010, 150: 420–427.

Bejarano V, Quinn M, Conaghan PG, Reece R, Keenan AM, Walker D, Gough A, Green M, McGonagle D, Adebajo A, Jarrett S, Doherty S, Hordon L, Melsom R, Unnebrink K, Kupper H, Emery P, Yorkshire Early Arthritis Register Consortium: Effect of the early use of the anti-tumor necrosis factor adalimumab on the prevention of job loss in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2008, 59: 1467–1474.

Bennett RM, Kamin M, Karim R, Rosenthal N: Tramadol and acetaminophen combination tablets in the treatment of fibromyalgia pain: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study. Am J Med 2003, 114: 537–545.

Bennett RM, Schein J, Kosinski MR, Hewitt DJ, Jordan DM, Rosenthal NR: Impact of fibromyalgia pain on health-related quality of life before and after treatment with tramadol/acetaminophen. Arthritis Rheum 2005, 53: 519–527.

Bradley LA, Bennett R, Russell IJ, Wohlreich MM, Chappell AS, Wang F, D’Souza DN, Moldofsky H: Effect of duloxetine in patients with fibromyalgia: tiredness subgroups. Arthritis Res Ther 2010, 12: R141.

Carlsson CP, Sjölund BH: Acupuncture for chronic low back pain: a randomized placebo-controlled study with long-term follow-up. Clin J Pain 2001, 17: 296–305.

Chappell AS, Bradley LA, Wiltse C, Detke MJ, D’Souza DN, Spaeth M: A six-month double-blind, placebo-controlled, randomized clinical trial of duloxetine for the treatment of fibromyalgia. Int J Gen Med 2008, 1: 91–102.

Chappell AS, Ossanna MJ, Liu-Seifert H, Iyengar S, Skljarevski V, Li LC, Bennett RM, Collins H: Duloxetine, a centrally acting analgesic, in the treatment of patients with osteoarthritis knee pain: a 13-week, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Pain 2009, 146: 253–260.

Chappell AS, Desaiah D, Liu-Seifert H, Zhang S, Skljarevski V, Belenkov Y, Brown JP: A double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study of the efficacy and safety of duloxetine for the treatment of chronic pain due to osteoarthritis of the knee. Pain Pract 2011, 11: 33–41.

Egsmose C, Hansen TM, Andersen LS, Beier JM, Christensen L, Ejstrup L, Peters ND, van der Heijde DM: Limited effect of sulphasalazine treatment in reactive arthritis. A randomised double blind placebo controlled trial. Ann Rheum Dis 1997, 56: 32–36.

He D, Høstmark AT, Veiersted KB, Medbø JI: Effect of intensive acupuncture on pain-related social and psychological variables for women with chronic neck and shoulder pain–an RCT with six month and three year follow up. Acupunct Med 2005, 23: 52–61.

Jarzem PF, Harvey EJ, Arcaro N, Kaczorowski J: Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation [TENS] for chronic low back pain. J Musculoskelet Pain 2005, 13: 3–9.

Kavanaugh A, Antoni C, Mease P, Gladman D, Yan S, Bala M, Zhou B, Dooley LT, Beutler A, Guzzo C, Krueger GG: Effect of infliximab therapy on employment, time lost from work, and productivity in patients with psoriatic arthritis. J Rheumatol 2006, 33: 2254–2259.

Kavanaugh A, Smolen JS, Emery P, Purcaru O, Keystone E, Richard L, Strand V, van Vollenhoven RF: Effect of certolizumab pegol with methotrexate on home and work place productivity and social activities in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2009, 61: 1592–1600.

Kavanaugh A, McInnes IB, Krueger GG, Gladman D, Beutler A, Gathany T, Mack M, Tandon N, Han C, Mease P: Patient-reported outcomes and the association with clinical response in patients with active psoriatic arthritis treated with golimumab: findings through 2 years of a phase III, multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Care Res 2013, 65: 1666–1673.

Lehmann TR, Russell DW, Spratt KF, Colby H, Liu YK, Fairchild ML, Christensen S: Efficacy of electroacupuncture and TENS in the rehabilitation of chronic low back pain patients. Pain 1986, 26: 277–290.

Licciardone JC, Stoll ST, Fulda KG, Russo DP, Siu J, Winn W, Swift J Jr: Osteopathic manipulative treatment for chronic low back pain: a randomized controlled trial. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2003, 28: 1355–1362.

Manchikanti L, Singh V, Falco FJ, Cash KA, Fellows B: Comparative outcomes of a 2-year follow-up of cervical medial branch blocks in management of chronic neck pain: a randomized, double-blind controlled trial. Pain Physician 2010, 13: 437–450.

Markenson JA, Croft J, Zhang PG, Richards P: Treatment of persistent pain associated with osteoarthritis with controlled-release oxycodone tablets in a randomized controlled clinical trial. Clin J Pain 2005, 21: 524–535.

Meireles SM, Jones A, Jennings F, Suda AL, Parizotto NA, Natour J: Assessment of the effectiveness of low-level laser therapy on the hands of patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a randomized double-blind controlled trial. Clin Rheumatol 2010, 29: 501–509.

Skljarevski V, Ossanna M, Liu-Seifert H, Zhang Q, Chappell A, Iyengar S, Detke M, Backonja M: A double-blind, randomized trial of duloxetine versus placebo in the management of chronic low back pain. Eur J Neurol 2009, 16: 1041–1048.

Skljarevski V, Desaiah D, Liu-Seifert H, Zhang Q, Chappell AS, Detke MJ, Iyengar S, Atkinson JH, Backonja M: Efficacy and safety of duloxetine in patients with chronic low back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2010a, 35: E578-E585.

Skljarevski V, Zhang S, Desaiah D, Alaka KJ, Palacios S, Miazgowski T, Patrick K: Duloxetine versus placebo in patients with chronic low back pain: a 12-week, fixed-dose, randomized, double-blind trial. J Pain 2010b, 11: 1282–1290.

Smolen JS, Han C, van der Heijde D, Emery P, Bathon JM, Keystone E, Kalden JR, Schiff M, Bala M, Baker D, Han J, Maini RN, St Clair EW: Infliximab treatment maintains employability in patients with early rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2006, 54: 716–722.

Strand V, Tugwell P, Bombardier C, Maetzel A, Crawford B, Dorrier C, Thompson A, Wells G: Function and health-related quality of life: results from a randomized controlled trial of leflunomide versus methotrexate or placebo in patients with active rheumatoid arthritis. Leflunomide Rheumatoid Arthritis Investigators Group. Arthritis Rheum 1999, 42: 1870–1878.

van der Heijde D, Han C, DeVlam K, Burmester G, van den Bosch F, Williamson P, Bala M, Han J, Braun J: Infliximab improves productivity and reduces workday loss in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: results from a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum 2006, 55: 569–574.

Arnold LM, Lu Y, Crofford LJ, Wohlreich M, Detke MJ, Iyengar S, Goldstein DJ: A double-blind, multicenter trial comparing duloxetine with placebo in the treatment of fibromyalgia patients with or without major depressive disorder. Arthritis Rheum 2004, 50: 2974–2984.

Russell IJ, Mease PJ, Smith TR, Kajdasz DK, Wohlreich MM, Detke MJ, Walker DJ, Chappell AS, Arnold LM: Efficacy and safety of duloxetine for treatment of fibromyalgia in patients with or without major depressive disorder: results from a 6-month, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, fixed-dose trial. Pain 2008, 136: 432–444.

Straube S, Derry S, Moore RA, Paine J, McQuay HJ: Pregabalin in fibromyalgia–responder analysis from individual patient data. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2010, 11: 150.

Antoni C, Krueger GG, deVlam K, Birbara C, Beutler A, Guzzo C, Zhou B, Dooley LT, Kavanaugh A: Infliximab improves signs and symptoms of psoriatic arthritis: results of the IMPACT 2 trial. Ann Rheum Dis 2005, 64: 1150–1157.

Van der Heijde D, Dijkmans B, Geusens P, Sieper J, DeWoody K, Williamson P, Braun J, Ankylosing Spondylitis Study for the Evaluation of Recombinant Infliximab Therapy Study Group: Efficacy and safety of infliximab in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: results of a randomized, placebo-controlled trial (ASSERT). Arthritis Rheum 2005, 52: 582–591.

Patel AS, Farquharson R, Carroll D, Moore A, Phillips CJ, Taylor RS, Barden J: The impact and burden of chronic pain in the workplace: a qualitative systematic review. Pain Pract 2012, 12: 578–589.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

SS has participated in grants from Pfizer and Reckitt-Benckiser and has received a lecture fee and an honorarium from Oxford Medical Knowledge for work on data from pain trials. TF is a consultant to Novartis Pharma AG, Biogen Idec, Phamalog and Grünenthal.

Authors’ contributions

IW did the searching, data extraction, and study quality assessment, performed the analyses, and made the figures and tables. SS conceived of the study, supervised IW for his doctoral dissertation on this subject, and drafted the manuscript. TF provided statistical advice for the analysis and also supervised IW for his doctoral dissertation. All authors contributed to revising the manuscript and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

12995_2014_271_MOESM1_ESM.pdf

Additional file 1: Excluded studies. This file contains a table of excluded studies, with brief reasons for their exclusion and the references of the excluded studies. (PDF 179 KB)

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Wolf, I., Friede, T., Hallier, E. et al. Work-related outcomes in randomised placebo-controlled pain trials: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Occup Med Toxicol 9, 25 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1745-6673-9-25

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1745-6673-9-25