Abstract

We herein report a case of spontaneous rectal expulsion of an ileal lipoma in a 65-year-old female patient who presented with recurrent attacks of subacute intestinal obstruction. During each episode, the patient developed severe abdominal pain and expelled a fleshy mass from her rectum. The fleshy mass was histopathologically diagnosed as a lipoma comprising fat cells, fibers, and blood vessels. Upon expulsion, the pain disappeared and the intussusception was immediately resolved. Colonoscopic examination revealed a 2.5-cm diameter ulcerated lesion near the ileocecal valve, which was confirmed to be inflammation by pathological examination. A subsequent barium series revealed a normal colonic tract, and the patient remained completely symptom-free for 4 months after the incident. According to the relevant literature and our clinical experience, the treatment method for a lipoma depends on the patient’s clinical manifestations and the size of the tumor. However, the various diagnostic and therapeutic modalities currently available continue to be debated; whether an asymptomatic lipoma requires treatment is controversial. When histopathological examination results allow for the exclusion of malignant lesions such as sarcoma, a lipoma can be resected surgically.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Small intestinal tumors are extremely rare, accounting for only 1% to 2% of gastrointestinal tumors worldwide [1], and only around 30% of small intestinal tumors are benign. Lipoma, which is less prevalent than leiomyoma and adenoma, is the third most common primary benign tumor in the gut [2]. Small bowel tumors are rare entities that often present with nonspecific symptoms. When these tumors are >2 cm in diameter, abdominal pain, hematochezia, and/or incomplete intestinal obstruction may appear. The lack of specific clinical manifestations makes it difficult to reach a definite preoperative diagnosis; sometimes the lipoma is even ignored after the development of an intussusception. Moreover, it is difficult to identify symptomatic patients with malignant tumors, which can consequently be misdiagnosed. Most intestinal lipomas are located in the distal ileum and colorectal region (mainly the right colon) and are rarely located in the stomach or proximal small intestine. Intestinal lipomas seldom deteriorate, and they do not relapse after cure.

Intussusception was reported for the first time in 1674 by Barbette of Amsterdam [3]. The development of intussusception in adults is extremely rare and has a variety of etiologies. Neoplasia is the most common cause and is present in approximately 65% of adult intussusception cases [4]. Adult patients with intussusception may or may not be symptomatic, and symptoms can be acute, intermittent, or chronic. Therefore, intussusception is difficult to diagnose. The manifestations of symptomatic lipoma include abdominal pain, hemorrhage, or incomplete intestinal obstruction. Because of their intramural location, lipomas can also serve as the leading point for intussusceptions. A correct and timely diagnosis is important to avoid complications such as bowel infarction and perforation secondary to obstruction.

Case presentation

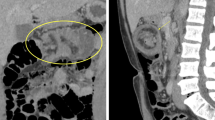

A 65-year-old woman was admitted to the emergency department with a 3-year history of intermittent abdominal pain that was exacerbated and accompanied by nausea for the past 5 days. The pain was moderate, paroxysmal, and colicky in nature; it was present mainly in the right lower quadrant and radiated to the back. She had no fever and reported intermittent defecation without nausea or vomiting. The patient had previously been seen at another hospital, where abdominal ultrasound and computed tomography (CT) examination revealed either a smooth, well-circumscribed mass within the lumen of the bowel or an intussusception. Her symptoms improved after conservative treatment. Physical examination revealed tenderness in the right lower quadrant and a smooth, well-circumscribed mass of approximately 7.0 × 5.0 cm was palpated in the epigastrium. Abdominal CT revealed a small bowel intussusception in the right epigastric region (Figure 1A and B).

Transverse and coronary contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CECT) of the abdomen. (A) Transverse CECT showed the bowel intussusception (white arrow) entered the intestinal lumen on the right middle abdomen. Enhanced blood vessel (yellow arrow) also entered the intestinal lumen along with the bowel. (B) Coronary CECT showed that the tumor was located at the splenic flexure of the colon (blue arrow) and was accompanied by local intestinal expansion.

The patient had no history of surgery, trauma, or other diseases. Laboratory test results showed a white blood cell count of 7.80 × 109/L, a neutrophil level of 71.3%, and a hemoglobin level of 104 g/L. Other examination results were normal. The preliminary diagnosis was considered to be an intestinal tumor with intussusception.

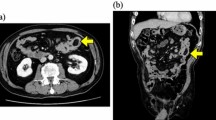

After admission, the patient was treated with oral therapy for bowel lubrication and experienced gradual relief of her abdominal pain. A vegetative mass was then extruded from the rectum when the patient defecated. However, it could not be completely discharged. Digital rectal examination revealed a well-circumscribed neoplasm with poor mobility in the center of the rectal lumen. A small amount of blood was present on the glove after digital examination. Abdominal CT showed a mass shadow in the ileocecal valve region with a maximum size of approximately 2.90 × 3.22 cm (Figure 2A) and an expanded rectum with fat density and space within a shadow (Figure 2B). We actively enlarged the anus and administered a strong oral laxative. The patient then successfully defecated the mass. The mass was approximately 7.0 × 4.5 × 3.6 cm in size and of medium hardness; it had a smooth gray surface and a fine texture (Figure 3A). Microscopic examination showed fat cells, blood vessels, and fiber cells arranged in a leaf pattern, with no heterogeneous nucleus or seedless division in the submucosal layer. The pathologic diagnosis was a bleeding submucosal lipoma with intestinal mucosal necrosis (Figure 3B).

Tumor and histopathological features. (A) A mass section showed a gray surface and fine texture by formalin infiltration. (B) Microscopic examination showed fat cells, blood vessels, and fiber cells arranged in a leaf pattern, with no heterogeneous nucleus or seedless division in the submucosal layer (hematoxylin and eosin staining, ×40).

After expulsion of the mass, the abdominal pain was completely relieved. Follow-up abdominal CT showed that the mass in the splenic flexure of the colon had disappeared and that the intussusception had been resolved. Colonoscopy showed an ulcerative lesion approximately 2.5 cm in diameter near the ileocecal valve that was surrounded by mucosal congestion (Figure 4A). Microscopic examination revealed regularly arranged glands; the epithelia were not atypical, but interstitial edema, eosinophils, and lymphocyte infiltration were present (Figure 4B). The pathologic diagnosis was inflammation of the ileocecal valve. Four months later, colonoscopy indicated that the inflammation of the ileocecal valve had healed and that the mucosa was intact. Subsequent capsule endoscopy and enteroscopy examination demonstrated no pathological changes.

Colonoscopy and histopathological features. (A) Colonoscopy showed an approximately 2.5-cm diameter ulcerative lesion (blue arrow) near the ileocecal valve, surrounded by mucosal congestion. (B) Microscopic examination showed regularly arranged glands and epithelia with no atypia, but interstitial edema, eosinophils, and lymphocyte infiltration were present (hematoxylin and eosin staining, ×100).

Discussion

When the lipoma moved to the splenic flexure, as in this case, abdominal CT still showed signs of intussusception, indicating that the mass was connected to a pedicle. The long duration of the intussusception, the gravity of the lipoma, and the presence of intestinal peristalsis gave rise to ischemia, necrosis, and breakage of the pedicle. Thus, the lipoma fell from the descending colon to the rectum, and the intussusception was resolved. After anal dilatation and catharsis treatment, the mass was spontaneously expelled. Abdominal CT and colonoscopy showed the mass shadow with an ulcerative lesion near the ileocecal valve as well as congestion of the surrounding mucosa. We consider that the mass shadow was caused by intestinal edema and thickening. The ulcerative lesion may have been caused by the impression of the mass when it fell to the ileocecal valve.

An intestinal lipoma is a benign tumor that can appear in any part of the gut. The terminal ileum is the most common location in the small intestine. There are three pathological types of intestinal lipomas. The submucosal type is the most common, accounting for more than 90% of intestinal lipomas, and grows within the submucosal layer, protruding into the lumen. The intermuscular type is located within the muscular layer. The subserosal type, which is asymptomatic, grows within the subserosal layer and protrudes out of the gut. Larger lipomas can be palpated as a smooth, movable abdominal lump. The tumor in our case was a submucosal lipoma. The patient spontaneously expelled the lipoma from her rectum before the development of intestinal ischemia and necrosis, and the intussusception was resolved spontaneously.

Imaging examination and colonoscopy contribute to the preoperative diagnosis of intestinal lipomas. Intestinal lipomas can be diagnosed by conventional endoscopy, capsule endoscopy, and barium examination. The presence of a round filling defect with or without a pedicle in the lumen on barium enema examination or small intestinal barium enema intubation examination indicates a lipoma. Ultrasound is usually the first diagnostic modality chosen, especially when the lipoma is accompanied by intestinal intussusception. The characteristic ultrasound finding associated with an intussusception is the “target sign”, in which the outermost layer represents the sheath, and the multilayer ring structure represents the invaginated intestinal segment. In some cases, ultrasonography can show a suborbicular nested mass with a clear boundary, low blood supply, and strong ultrasonic echo. These findings may indicate a lipoma. However, ultrasonography is generally limited to the demonstration of intestinal dilation and obstruction. CT is the most valuable diagnostic method for intestinal intussusception, and it can clearly reveal the typical characteristics of uniform tumor density, a clear border, no reinforcement, and fat (negative) density, allowing for a definite diagnosis [5]. Colonoscopy is also valuable in the diagnosis of intestinal lipoma. Microscopically, a lipoma is characterized as follows: i) it presents as an orange, smooth, submucosal mass protruding into the intestinal lumen with or without a pedicle; ii) the mass can immediately recover from local compression using biopsy forceps (the so-called “cushion sign”); and iii) after repeated biopsy of a certain part of the tumor, the submucosal adipose tissue is visible (termed “naked fat”) [6]. However, endoscopy is of little significance for the diagnosis of intestinal lipoma.

We searched the PubMed database to gain a deeper understanding of lipomas in the small intestine. The following search terms were used: ((lipoma [MeSH Terms]) OR lipoma) AND ((intestine, small [MeSH Terms]) OR small intestine OR small bowel) AND (English [Language]) AND (intussusception [MeSH Terms]). Only 51 eligible articles were retrieved. We excluded articles that described secondary cases or the imaging characteristics of lipomas in the small intestine and only 27 articles remained [7–33] (Table 1).

According to the literature, most lipomas are asymptomatic. They may present as intestinal obstruction or hemorrhage [34]. The lack of specific clinical manifestations makes small intestinal lipomas difficult to diagnose. Their usual location in the small intestine is the ileum. The peak age of incidence is the sixth to seventh decade of life. Despite the development of imaging techniques, only 32% to 50% of cases are diagnosed preoperatively [35]. Intestinal lipomas >2 cm in diameter can cause intussusception. The typical triad of abdominal pain, a sausage-shaped mass, and red jelly stools is seen in children, but rarely in adults. Adult intussusception is a very rare condition, accounting for only around 5% of all intussusception cases and 1% of adult intestinal obstructions [36]. If a lipoma is <2 cm in diameter, it can be resected via endoscopy. However, this method is risky for lipomas with no pedicle. Because fat is a poor conductor, it does not readily solidify after electric coagulation. Bleeding and deep tissue damage may occur. The electric current accumulation during coagulation greatly contributes to the risk of intestinal perforation. Therefore, local intestinal resection is the optimal treatment method. When a lipoma causes intussusception, the intestinal tract should be intraoperatively reset and the local intestine then resected. Otherwise, intestinal resection with anastomosis is feasible. If the condition cannot be diagnosed preoperatively, intraoperative pathological examination helps to determine the best surgical treatment method. In addition, some colonic lipomas are accompanied by colorectal cancer. The intestinal tract should be thoroughly explored during surgery to prevent misdiagnosis.

Definitive surgical resection remains the recommended treatment for adult intussusceptions due to the large proportion of structural causes and the relatively high incidence of malignancy. However, the most optimal surgical management technique remains controversial. Some investigators have stated that small bowel intussusceptions should be reduced only in patients in whom a definitive benign diagnosis has been made preoperatively and should be avoided in patients in whom resection may result in short-bowel syndrome [35]. All surgeons agree that intestinal resection is optimal if there are signs of irreversible bowel ischemia, inflammation, or suspected malignancy [37]. Otherwise, reduction is appropriate, especially when the small bowel is affected, because a considerable length of the bowel can be preserved, thereby preventing the development of short-bowel syndrome.

Conclusions

In summary, the treatment of intestinal lipoma depends on the clinical manifestations and the size of the tumor. Whether small asymptomatic lipomas need further treatment remains controversial. For symptomatic lipomas, operative resection can be performed to histopathologically exclude liposarcoma and malignant lesions. Laparoscopic operative resection is superior to the traditional open operation. In the presence of complications such as acute intestinal obstruction, intussusception, or massive hemorrhage, operative treatment is recommended. In patients with intestinal ischemia, necrosis, or suspected malignancy, intestinal resection and anastomosis is feasible. Otherwise, reduction is appropriate and prevents the development of short-bowel syndrome.

In this paper, we have described a case involving a lipoma in the terminal ileum. Ultrasonographic and whole-abdomen CT examination showed that the lipoma had caused an ileocolic intussusception and incomplete intestinal obstruction. After the onset of the ileocecal intussusception, the site slowly expanded toward the ascending colon, transverse colon, and splenic flexure of the colon. The lipoma finally fell to the rectum, and intussusception resolved spontaneously.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case and for the accompanying images.

Authors’ information

The English in this document has been checked by at least two professional editors, both native speakers of English. For a certificate, please see: http://www.textcheck.com/certificate/p5Hkrp.

Abbreviations

- CECT:

-

Contrast-enhanced computed tomography

- CT:

-

Computed tomography

- DBE:

-

Double-balloon endoscopy

- ERCP:

-

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography

- EUS:

-

Endoscopic ultrasonography

- MDCT:

-

Multidetector row computed tomography

- MRI:

-

Magnetic resonance imaging

- US:

-

Ultrasonography.

References

Good CA: Tumors of the small intestine. Am J Roentgenol Radium Ther Nucl Med. 1963, 89: 685-705.

Ashley SW, Wells SA: Tumors of the small intestine. Semin Oncol. 1988, 15: 116-128.

Krasniqi AS, Hamza AR, Salihu LM, Spahija GS, Bicaj BX, Krasniqi SA, Kurshumliu FI, Gashi-Luci LH: Compound double ileoileal and ileocecocolic intussusception caused by lipoma of the ileum in an adult patient: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2011, 5: 452. 10.1186/1752-1947-5-452.

Warshauer DM, Lee JK: Adult intussusception detected at CT or MR imaging: clinical-imaging correlation. Radiology. 1999, 212: 853-860. 10.1148/radiology.212.3.r99au43853.

Franc-Law JM, Begin LR, Vasilevsky CA, Gordon PH: The dramatic presentation of colonic lipomata: report of two cases and review of the literature. Am Surg. 2001, 67: 491-494.

Notaro JR, Masser PA: Annular colon lipoma: a case report and review of the literature. Surgery. 1991, 110: 570-572.

Esnakula AK, Sinha A, Fidelia-Lambert M, Tammana VS: Angiolipoma: rare cause of adult ileoileal intussusception. BMJ Case Rep. 2013, doi:10.1136/bcr-2013-008921

Pezzolla A, Lattarulo S, Caputi O, Ugenti I, Fabiano G, Piscitelli D: Colonic lipomas. Three surgical techniques for three different clinical cases. G Chir. 2012, 33: 420-422.

Lucas LC, Fass R, Krouse RS: Laparoscopic resection of a small bowel lipoma with incidental intussusception. JSLS. 2010, 14: 615-618. 10.4293/108680810X12924466008844.

Ako E, Morisaki T, Hasegawa T, Hirakawa T, Tachimori A, Nakazawa K, Yamagata S, Kanehara I, Nishimura S, Taenaka N: Laparoscopic resection of ileal lipoma diagnosed by multidetector-row computed tomography. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2010, 20: e226-e229. 10.1097/SLE.0b013e3182002ac4.

Chuang MT, Tsai KB, Ma CJ, Hsieh TJ: Ileoileal intussusception due to ileal ectopic pancreas with abundant fat tissue mimicking lipoma. Am J Surg. 2010, 200: e25-e27. 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2009.12.027.

Wan XY, Deng T, Luo HS: Partial intestinal obstruction secondary to multiple lipomas within jejunal duplication cyst: a case report. World J Gastroenterol. 2010, 16: 2190-2192. 10.3748/wjg.v16.i17.2190.

Di Saverio S, Tugnoli G, Ansaloni L, Catena F, Biscardi A, Jovine E, Baldoni F: Concomitant intestinal obstruction: a misleading diagnostic pitfall. BMJ Case Rep. 2010, doi: 10.1136/bcr.08.2009.2177

Whitfield JD, Mostafa G: Images in clinical medicine. Ileocecal intussusception. N Engl J Med. 2009, 361: e55. 10.1056/NEJMicm0808287.

Kuzmich S, Connelly JP, Howlett DC, Kuzmich T, Basit R, Doctor C: Ileocolocolic intussusception secondary to a submucosal lipoma: an unusual cause of intermittent abdominal pain in a 62-year-old woman. J Clin Ultrasound. 2010, 38: 48-51.

Akagi I, Miyashita M, Hashimoto M, Makino H, Nomura T, Tajiri T: Adult intussusception caused by an intestinal lipoma: report of a case. J Nippon Med Sch. 2008, 75: 166-170. 10.1272/jnms.75.166.

Lin MW, Chen KH, Lin HF, Chen HA, Wu JM, Huang SH: Laparoscopy-assisted resection of ileoileal intussusception caused by intestinal lipoma. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2007, 17: 789-792. 10.1089/lap.2007.0035.

Oyen TL, Wolthuis AM, Tollens T, Aelvoet C, Vanrijkel JP: Ileo-ileal intussusception secondary to a lipoma: a literature review. Acta Chir Belg. 2007, 107: 60-63.

Rathore MA, Andrabi SI, Mansha M: Adult intussusception–a surgical dilemma. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad. 2006, 18: 3-6.

McKay R: Ileocecal intussusception in an adult: the laparoscopic approach. JSLS. 2006, 10: 250-253.

Ahmed HU, Wajed S, Krijgsman B, Elliot V, Winslet M: Acute abdomen secondary to a Meckel’s lipoma. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2004, 86: W4-W5.

Zissin R: Enteroenteric intussusception secondary to a lipoma: CT diagnosis. Emerg Radiol. 2004, 11: 107-109. 10.1007/s10140-004-0378-8.

Marino F, Lobascio P, Martines G, Di Franco AD, Rinaldi M, Altomare DF: Double jejunal intussusception in an adult with chronic subileus due to a giant lipoma: a case report. Chir Ital. 2005, 57: 239-242.

Meshikhes AW, Al-Momen SA, Al Talaq FT, Al-Jaroof AH: Adult intussusception caused by a lipoma in the small bowel: report of a case. Surg Today. 2005, 35: 161-165. 10.1007/s00595-004-2899-x.

Moues CM, Steenvoorde P, Viersma JH, van Groningen K, de Bruine JF: Jejunal intussusception of a gastric lipoma: a review of literature. Dig Surg. 2002, 19: 418-420. 10.1159/000065825.

Watanabe F, Honda S, Kubota H, Higuchi R, Sugimoto K, Iwasaki H, Yoshino G, Kanamaru H, Hanai H, Yoshii S, Kaneko E: Preoperative diagnosis of ileal lipoma by endoscopic ultrasonography probe. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2000, 31: 245-247. 10.1097/00004836-200010000-00014.

Ross GJ, Amilineni V: Case 26: Jejunojejunal intussusception secondary to a lipoma. Radiology. 2000, 216: 727-730. 10.1148/radiology.216.3.r00se33727.

Urbano J, Serantes A, Hernandez L, Turegano F: Lipoma-induced jejunojejunal intussusception: US and CT diagnosis. Abdom Imaging. 1996, 21: 522-524. 10.1007/s002619900118.

Gates LK, Keate RF, Smalley JJ, Richardson JD: Macrodactylia fibrolipomatosis complicated by multiple small bowel lipomas and intussusception. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1996, 23: 241-242. 10.1097/00004836-199610000-00021.

McGrath FP, Moote DJ, Langer JC, Orr W, Somers S: Duodenojejunal intussusception secondary to a duodenal lipoma presenting in a young boy. Pediatr Radiol. 1991, 21: 590-591. 10.1007/BF02012606.

Misra SP, Singh SK, Thorat VK, Gulati P, Malhotra V, Anand BS: Spontaneous expulsion per rectum of an ileal lipoma. Postgrad Med J. 1988, 64: 718-719. 10.1136/pgmj.64.755.718.

Donovan AT, Goldman SM: Computed tomography of ileocecal intussusception: mechanism and appearance. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 1982, 6: 630-632. 10.1097/00004728-198206000-00035.

Schnur MJ, Seaman WB: Prolapsing neoplasms of the terminal ileum simulating enlarged ileocecal valves. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1980, 134: 1133-1136. 10.2214/ajr.134.6.1133.

Balamoun H, Doughan S: Ileal lipoma - a rare cause of ileocolic intussusception in adults: case report and literature review. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2011, 3: 13-15. 10.4240/wjgs.v3.i1.13.

Namikawa T, Hokimoto N, Okabayashi T, Kumon M, Kobayashi M, Hanazaki K: Adult ileoileal intussusception induced by an ileal lipoma diagnosed preoperatively: report of a case and review of the literature. Surg Today. 2012, 42: 686-692. 10.1007/s00595-011-0092-6.

Bilgin M, Toprak H, Ahmad IC, Yardimci E, Kocakoc E: Ileocecal intussusception due to a lipoma in an adult. Case Rep Surg. 2012, 2012: 684298-

Hadithi M, Heine GD, Jacobs MA, van Bodegraven AA, Mulder CJ: A prospective study comparing video capsule endoscopy with double-balloon enteroscopy in patients with obscure gastrointestinal bleeding. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006, 101: 52-57. 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.00346.x.

Acknowledgments

We thank Prof. Dong Shang for assisting in the preparation of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

All authors have made substantive contributions to the study, and are in agreement with the conclusions of the study. Furthermore, there are no financial competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

BK and QZ searched the database, selected the articles, and wrote the manuscript. FM supervised the writing of the manuscript. QN, LH, and WC managed the figures. DS supervised the methodology, the selection of the articles, and the writing of the manuscript and is the corresponding author of the paper. All authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Kang, B., Zhang, Q., Shang, D. et al. Resolution of intussusception after spontaneous expulsion of an ileal lipoma per rectum: a case report and literature review. World J Surg Onc 12, 143 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7819-12-143

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1477-7819-12-143