Abstract

Background

This study aimed to assess the relationship between cold temperature and daily mortality in the Republic of Ireland (ROI) and Northern Ireland (NI), and to explore any differences in the population responses between the two jurisdictions.

Methods

A time-stratified case-crossover approach was used to examine this relationship in two adult national populations, between 1984 and 2007. Daily mortality risk was examined in association with exposure to daily maximum temperatures on the same day and up to 6 weeks preceding death, during the winter (December-February) and an extended cold period (October-March), using distributed lag models. Model stratification by age and gender assessed for modification of the cold weather-mortality relationship.

Results

In the ROI, the impact of cold weather in winter persisted up to 35 days, with a cumulative mortality increase for all-causes of 6.4% (95% CI = 4.8%-7.9%) in relation to every 1°C drop in daily maximum temperature, similar increases for cardiovascular disease (CVD) and stroke, and twice as much for respiratory causes. In NI, these associations were less pronounced for CVD causes, and overall extended up to 28 days. Effects of cold weather on mortality increased with age in both jurisdictions, and some suggestive gender differences were observed.

Conclusions

The study findings indicated strong cold weather-mortality associations in the island of Ireland; these effects were less persistent, and for CVD mortality, smaller in NI than in the ROI. Together with suggestive differences in associations by age and gender between the two Irish jurisdictions, the findings suggest potential contribution of underlying societal differences, and require further exploration. The evidence provided here will hope to contribute to the current efforts to modify fuel policy and reduce winter mortality in Ireland.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

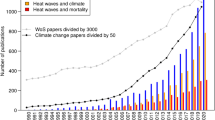

The impacts of cold weather on human health are increasingly being evidenced by epidemiologic studies, contributing to a wide range of public health outcomes including increased mortality from cardiovascular, cerebrovascular and respiratory diseases [1–3]. Under the influences of global climate change, both mean temperature and temperature variability are expected to increase globally, likely affecting the increasing frequency of weather extremes [4, 5]. Recent record low temperatures in Northern Europe and the United States highlight the potential health and societal impacts of extreme winter weather, despite the rise in global average temperatures [3, 6]. The large death toll and the disruption associated with the cold weather in Europe in the winter of 2005–2006 was a timely reminder of how poorly prepared many populations were to the dangers of extreme cold temperatures [7].

Although there has been a general trend of rising average temperatures in Ireland over the past 30 years, the island has witnessed extreme cold weather events over the same period [8, 9]. Taking into consideration the differences in underlying population health, public policies targeted at preventing winter mortality, health care provision, and socioeconomic and demographic construct of the two Irish jurisdictions [10–12], the health impacts of cold weather could potentially differ.

It is therefore important to understand the magnitude and geographic differences of the cold weather-health relationship on the island of Ireland in order to inform public policies aimed at improvement of population health, and targeting of vulnerable groups during periods of cold weather. This study aimed to assess the cold temperature and all-cause and cause-specific mortality relationship in the Republic of Ireland (ROI) and Northern Ireland (NI), and to assess for modification of this relationship by age and gender.

Methods

Mortality

Individual daily deaths for ages ≥18 years were obtained from the Irish Central Statistics Office for data in the ROI, and Northern Ireland Social Research Agency for data in NI for the period of January 1st 1984 and December 31st 2007. International Classification of Disease-9 (ICD-9) codes were used up to 2006, and ICD-10 codes from 2007. Non-accidental deaths were used for this study (ICD-9 codes 001-799/ICD-10 codes A00-R99), further categorised to primary cause-specific mortality for cardiovascular disease (CVD) (390–429; I01-I52), ischaemic heart disease (IHD) (410–414, 429.2; I20-I52), myocardial infarction (MI) (410; I21-I22), respiratory disease (460–519; J0-J99), pneumonia (480–486; J12-J18), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) (490–492, 494–496; J40-J44, J47), and stroke (430–438; I60-I69).

Weather data

Full time-series weather data for the study period were obtained from Met Eireann, for ten weather stations in the ROI; and from the United Kingdom Meteorological Office for six weather stations in NI. The data included daily maximum, minimum, and mean temperatures, relative humidity and atmospheric pressure, and were merged on daily mortality data by county, based on geographical proximity to weather stations.

Statistical analyses

A time-stratified case-crossover approach was applied to assess the associations between cold weather and daily mortality in each of the two Irish jurisdictions. The case-crossover design has been originally developed and used in air pollution studies, and has been extensively described elsewhere [13–15]. Briefly, the approach is a variant of the case–control study, comparing each person’s exposure at the time of death (case time) with that person’s exposure in other times (control times) [13]. A time-stratified approach is used to select control days, with the day of death chosen as the case day, and controls chosen as all other days, the same day of the week, in the same month and year as the case day, leaving two days between each control to eliminate any serial correlation [14, 15]. An advantage of this design is that, if control days are chosen close in time to the day of death, there is no confounding by slowly varying personal characteristics, and even very strong confounding by season and time trend can be removed [16–18]. Conditional logistic regression was applied to matched pairs to compare the different characteristics between the case day and its control days [13]. The choice of the modeling approach was determined after data were tested that model assumptions were met, and no important data overdispersion was present [19].

Definition of seasons

Data were analyzed for the winter season (December-February) and an extended cold period (October-March). To investigate whether the observed cold weather-mortality effects were not just confined to winter months, separate analyses were also carried out for the other months in the extended cold period (October, November, and March). Cold weather-related mortality increases were observed during the extended cold period; however these associations were weaker and less persistent than those observed in winter, and will not be discussed further.

Temperature metrics

Different temperature definitions have been used in literature with no uniform criteria used to identify the best cold weather exposure metric [20, 21]. In this study, daily maximum, mean and minimum temperatures were tested as exposure metrics in the models. Strongest mortality associations were obtained with daily maximum temperature, with only small differences between this and associations with mean temperature; these were slightly greater than those observed for minimum temperature. It was, therefore, decided to present results only for maximum temperature. To assess the impact of temperature variability on mortality, associations with temperature differences between daily maximum and minimum temperature, daily maximum and mean temperature, and weekly mean maximum and minimum temperature were examined as independent variables in the models. None of these associations were statistically important, and thus are not presented here.

Definition of exposure variables

Daily mortality in association with exposure to temperatures on the same day of the death (lag0) up to 6 weeks prior to the death (lag1-42 days) was examined. Weekly means of daily maximum temperatures were calculated for each of the 6 weeks, for lag1-7, 8–14, 15–21, 22–28, 29–35, and 36–42 days. Distributed lag models included all weekly lags, with lag0 included as an independent variable. This model is a way to estimate unbiased time trends of the exposure-response relation, by controlling for confounding in temperature-mortality associations in one lag structure by exposure to cold temperature in other lags [17]. Models were also tested with a finer definition of lag structure (means of lag1-2, 3–5, 6–9, 10–14, 15–21, 22–28 and 29–35 days) to examine acute, medium and longer term effects of temperatures. However, the models were more efficient with fewer lag structures and overall results were similar. All models included ‘day of the week’ as an indicator variable, with Monday as the reference, relative humidity and atmospheric pressure averaged over 3 days: the day of death and two days prior. No important contributions of relative humidity and atmospheric pressure were found in other lag structures.

No associations were observed between any mortality cause and temperature in week 6 prior to death (lag35-42 days) in both jurisdictions. Important associations were observed with temperatures up to 35 days before death for the ROI, and up to 28 days for NI during winter, and only those were presented here.

Cumulative mortality increase estimate calculation

Estimates for important associations between daily mortality and lags of weekly average of maximum temperature prior to death were used to calculate cumulative estimates of mortality increases by summing the coefficients. Cumulative estimates did not include the association of mortality with temperature on the same day (lag0). This association is consistent with previous studies that assessed the cold weather-mortality relationship [1, 22], where lag0 was positive and potentially suggestive of warm temperature effects. The overall cumulative estimate variance was computed using previously described algorithms [23].

Modifying variables

The modification of the temperature-mortality relationship was examined by stratifying the models by gender, and age in the following groups: ≥18-64, ≥65-74, and ≥75 years. Statistically important differences between cumulative estimates of strata of a potential modifier were tested by calculating the 95% confidence interval of this difference (95% CI) [24]. It is also possible that the response of the two populations to the cold temperatures has changed over time. To understand long term patterns of the cold weather-mortality association, additional analyses were carried out stratified for different time periods. In these analyses, some differences over time, with effects slightly diminishing in more recent years, were observed for both jurisdictions (data not shown).

The study did not consider adjustment for air pollution; these data were also inconsistent across the Island for the study period. Current practice in epidemiologic studies examining the weather and health association is to automatically adjust for air pollution, if information on this is available. In a recent article, Buckley et al. indicated that there is no known mechanism by which air pollution confounds the cold temperature and mortality (health) relationship [25]. In support of this rationale, previous epidemiologic studies show little or no influence of air pollution on the cold weather-mortality relationship [1–3, 22, 26–28]. This evidence emphasizes the robustness of our study findings, which are very important from a public policy perspective.

Results are presented as percentage (%) change in mortality per 1°C decrease in weekly average of daily maximum temperature.

Results

From the 24 years of the study data, there were a total of 709,110 non-accidental deaths in the ROI, and 347,936 in NI (Table 1). Of these deaths in the ROI, 33% were from CVD causes, 15% from respiratory diseases, and 9% from stroke, with NI showing a similar distribution. In both jurisdictions, more males died amongst ages ≥18 and 74 years; female deaths were greater in the ≥75 years age group. More than half of the deaths occurred in the ≥75 years old.

Overall, on average, temperatures in NI in winter were 1°C less than in the ROI, a trend which was reflected across all temperature metrics (Table 2).

Mortality-temperature associations for the winter season in the ROI are presented in Table 3. All-cause mortality showed the greatest increase associated with temperatures in the preceding week to death; the impact of cold temperature on mortality slightly weakened, but lasted up to 5 weeks prior to death. Similar associations were observed for CVD mortality; however, effects were seen up to the preceding 4 weeks. Respiratory mortality increases were strongest in relation to temperatures 2 weeks prior to death, and remained strong in weeks 3 to 4, extending, but slightly weakening into week 5. COPD and pneumonia mortality showed a similar pattern. Stroke mortality increases were observed in association with temperatures up to 3 weeks preceding death.

In the ROI, cumulative increases in mortality were calculated over the 5 week period for all-cause and respiratory disease; for a 4-week period for CVD mortality; and over the preceding 3 weeks for stroke. The cumulative increase for all-cause mortality was 6.4% (95% confidence interval-CI = 4.8%-7.9%). Similar cumulative increases were observed for CVD, and stroke mortality; increases for respiratory mortality were twice as large.

Table 4 presents the temperature-mortality associations during the winter months in NI. All-cause mortality showed important increases up to 3 weeks prior to death. The increases for CVD and stroke mortality were strongest in weeks 1 and 3. Respiratory mortality increased for cold temperatures 1 to 4 weeks prior, with similar associations observed for pneumonia. COPD mortality was associated with cold temperatures up to 3 weeks prior.

Cumulative mortality increases were calculated for associations with cold temperatures in the 4 weeks before death for all respiratory disease and pneumonia. For all other causes important effects were only seen up to the preceding week 3 and cumulative increases were only calculated over this period. Cumulative mortality increase for all-cause was 4.5% (95% CI = 3.2%-5.9%), for CVD 3.9% (95% CI = 1.5%-6.3%), respiratory disease 11.2% (95% CI = 7.1%-15.3%), and stroke 4.8% (95% CI = 0.9%-8.8%).

Some differences by age and gender in the cold weather-mortality associations were observed in both jurisdictions; however, overall these differences were not statistically important. Mortality increases in the ROI (Table 5) were mainly observed amongst ≥65 years old, and increased with age for all-cause and CVD. Stroke mortality increases were mainly amongst ≥75 years old, and females. No gender differences were observed for other mortality causes. In NI (Table 6), most of the cold weather-mortality impacts on all-cause and CVD were observed amongst ages ≥65 years; CVD and stroke mortality increases were only observed amongst males.

Discussion

This study observed strong associations between exposure to cold weather temperatures and mortality in two adult populations, in two Irish jurisdictions over a period of 24 years. Effects of cold weather were overall less persistent in NI than in the ROI. For most associations similar mortality patterns were observed for both jurisdictions. All-cause mortality associations were strongest in the week before death, weakening but extending up to 3 weeks in NI and 5 weeks in the ROI. A similar pattern was observed for CVD mortality, but effects were smaller and less persistent in NI than in the ROI. Cold weather up to 5 weeks before death in the ROI and up to 4 weeks in NI was associated with increases in all respiratory mortality; these increases were more extended and larger than for any other mortality group and cumulative increases were comparable in both jurisdictions, also consistent with findings of previous studies [1, 2, 22, 29]. Stroke mortality increases were seen for exposures up to 3 weeks prior to death, and associations were comparable in both jurisdictions. Overall the impacts of cold temperature on mortality were considerably higher and more persistent in winter, although some effects were still detectable in the other months of the extended cold period.

Different temperature metrics were examined in this study, and the strongest associations were observed for maximum temperature. These findings are in agreement with recent studies which suggest that maximum temperature is more likely to capture days that are consistently cold and extreme cold days [30, 31].

The findings here are also consistent with a previous Irish study [22] which examined the relationship between cold weather and mortality in Dublin over a period of 17 years, using Poisson regression models. They reported mortality increases for all-cause (2.6%), CVD (2.5%), and respiratory disease (6.7%) in relation to 1°C decrease in mean daily temperature up to 40 days preceding death. Similar results were observed in Scotland for all-cause, CVD and respiratory mortality with cold temperatures during the month prior death [29, 32]. Multi-city studies in Europe and the US reported similar increases for all-cause and cause-specific mortality from cold weather during winter and persistence of these associations, with similar lag periods as presented here [1, 2].

Only a small number of studies have looked at the association between cold temperature and mortality from COPD, pneumonia and stroke. An earlier study of 12 cold-climate US cities did not observe any increase in COPD mortality in relation to cold, but their reported increase for pneumonia mortality is comparable with those reported here [26]. Another US study reported elevated risk of dying of COPD associated with cold weather, in an elderly population [33]. Analitis et al. reported increases in stroke mortality associated with cold temperatures over 15 days before death [1], and other studies in Russia and Asia reported similar findings [31, 34, 35].

Weaker associations for CVD and stroke mortality were observed in relation to cold temperatures in the second week before death, with increases in mortality recovering in the week following. This phenomenon has been described previously as harvesting, which is likely due to the depletion in numbers by premature mortality of those most susceptible to cold weather [22, 36, 37]. The extended cold weather-mortality associations observed in our study suggest that there is potentially a cumulative health effect of cold weather and gradual weakening and displacement by death [22, 36, 37], also evidenced by a small number of epidemiologic studies that have considered long lag structures [1–3, 22, 32, 38].

Some suggestive differences in the cold weather-mortality associations by age and gender were observed in both jurisdictions. Corroborating our study findings, Analitis et al. and Goodman et al. reported increasing cold temperature-mortality associations with age [1, 22]; age or gender differences of this relationship have not been confirmed by other studies [7, 39].

This study observed some small differences in the associations of cold weather and mortality between the two Irish jurisdictions. The fact that the island of Ireland is relatively small, with similar weather, population characteristics and demographics, then any observed differences in the population response to the exposure to cold weather is most likely due to different public policies, socioeconomic construct, and health care systems in the two jurisdictions. Currently, there are winter fuel allowances and cold weather payments which target vulnerable population groups in both jurisdictions; however, these schemes differ substantially from each other [40–44]. The effectiveness of these cold weather and winter fuel payments in NI at reducing winter mortality have not been examined; in the ROI it has been suggested that the fuel allowance was not sufficient in meeting home-heating costs, and this was likely due to the contribution of poor thermal efficiency and low household income [11]. Rising fuel prices and demographic changes, combined with the economic recession have contributed to high levels of fuel poverty in the ROI, especially in relation to vulnerable households such as older people, those living alone and lone parent households [10, 12, 45, 46]. The jurisdictional differences in housing stock, insulation and heating, also related to socioeconomic deprivation, influence the extent of fuel poverty [11, 46, 47]. In addition, differences in the identification of the ‘fuel poor’ and ‘those most in need’ can also impact upon the effectiveness and differences of the schemes in the two jurisdictions [46, 48, 49].

A very strong relationship has been observed between the incidence of fuel poverty, social class, geographic and demographic patterns of those most susceptible on the island of Ireland [11, 47]. In both jurisdictions, the number of older people vulnerable to ill-health from cold homes will increase as part of significantly aging population [10]. Currently, there is a concentration of fuel poverty amongst rural older persons households in NI; fuel poverty is highest in most urbanized and very rural areas in the ROI [10, 11]. A greater proportion of older people in NI live alone and in social housing when compared to the ROI [10]. Jurisdictional differences in general population health status, provision of and access to health care, and distribution of health and social inequalities, potentially contribute in concurrence with these policies, and may explain some of the observed differences in the cold weather-mortality associations.

It is important to recognize that climate change induced weather patterns will affect the long term cold weather-mortality relationship. Research suggests that increasing global mean temperatures will do little to reduce morbidity and mortality in winter [4, 6, 50, 51], likely due to increases in temperature variability and weather extremes. These weather patterns have also been observed on the island of Ireland in the past few decades [8, 9]; on this basis only, it may be possible that winter mortality will change over time. However, whether this change will be an increase or decrease is much more complex and multifaceted, and will depend on how rapidly the climate changes, how quickly the population adapt, and on infrastructural and policy interventions, and remains a challenge particularly in view of the aging population on the Island. To understand long term patterns of the cold weather-mortality association, additional analyses were carried out to examine this relationship for different time periods in each jurisdiction. Findings suggested a slight diminishing of the cold weather-mortality relationship in both jurisdictions over time. These findings however, need to be interpreted with caution, considering the complexity of the relationship of mortality and cold winters and the influence of the societal factors discussed earlier.

Conclusions

This study found strong associations between cold temperatures and mortality with impacts of cold weather persisting up to several weeks, in both Irish jurisdictions. The findings show that increased mortality from cold weather on the island of Ireland is an important and topical public health issue. As the island of Ireland currently has the highest levels of excess winter mortality in Europe, with an estimated 2,800 excess deaths during each winter [12], the key challenges are to develop and implement policies which tackle fuel poverty and reduce winter morbidity and mortality. The fact that some differences in cold weather-mortality patterns are observed between the two jurisdictions, albeit small, suggests that policies and their implementation, and other societal factors potentially play a role in determining population health patterns.

Abbreviations

- °C:

-

Degrees celsius

- CI:

-

Confidence intervals

- COPD:

-

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

- CVD:

-

Cardiovascular disease

- ICD:

-

International classification of diseases

- IHD:

-

Ischemic heart disease

- MI:

-

Myocardial infarction

- NI:

-

Northern Ireland

- ROI:

-

The Republic of Ireland

- SD:

-

Standard deviation.

References

Analitis A, Katsouyanni K, Biggeri A, Baccini M, Forsberg B, Bisanti L, Kirchmayer U, Ballester F, Cadum E, Goodman PG, Hojs A, Sunyer J, Tiittanen P, Michelozzi P: Effects of cold weather on mortality: results from 15 European cities within the PHEWE project. Am J Epidemiol. 2008, 168: 1397-1408. 10.1093/aje/kwn266.

Anderson BG, Bell ML: Weather-related mortality: how heat, cold, and heat waves affect mortality in the United States. Epidemiology. 2009, 20: 205-213. 10.1097/EDE.0b013e318190ee08.

Barnett AG, Hajat S, Gasparrini A, Rocklov J: Cold and heat waves in the United States. Environ Res. 2012, 112: 218-224.

Field CB, Barros VR, Dokken DJ, Mach KJ, Mastrandrea MD, Bilir TE, Chatterjee M, Ebi KL, Estrada YO, Genova RC, Girma B, Kissel ES, Levy AN, MacCracken S, Mastrandrea PR, White LL: Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Part A: Global and Sectoral Aspects. Contribution of Working Group II to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. 2014, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA: Cambridge University Press, 1132-

McMichael AJ, Woodruff RE, Hales S: Climate change and human health: present and future risks. Lancet. 2006, 367: 859-869. 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68079-3.

Staddon PL, Montgomery HE, Depledge MH: Climate warming will not decrease winter mortality. Nature Climate Change. 2014, 4: 190-194. 10.1038/nclimate2121.

Hajat S, Kovats RS, Lachowycz K: Heat-related and cold-related deaths in England and Wales: who is at risk?. Occup Environ Med. 2007, 64: 93-100.

The United Kingdom Met Office: Past weather events. [http://www.metoffice.gov.uk/climate/uk/interesting#y2014]

Met Eireann, The Irish Meteorological Office: Major weather events. [http://www.met.ie/climate-ireland/major-events.asp]

Goodman P, McAvoy H, Cotter N, Monahan E, Barrett E, Browne S, Zeka A: Fuel Poverty, Older People and Cold Weather: An all-island analysis. Institute for Public Health in Dublin, Ireland. 2011, 130-

Healy JD, Clinch JP: Quantifying the severity of fuel poverty, its relationship with poor housing and reasons for non-investment in energy-saving measures in Ireland. Energy Policy. 2004, 32: 207-220. 10.1016/S0301-4215(02)00265-3.

McAvoy H: All-Ireland Policy Paper on Fuel Poverty and Health. Institute for Public Health in Dublin, Ireland. 2007, 20-

Maclure M: The case-crossover design: a method for studying transient effects on the risk of acute events. Am J Epidemiol. 1991, 133: 144-153.

Bateson TF, Schwartz J: Selection bias and confounding in case-crossover analyses of environmental time-series data. Epidemiology. 2001, 12: 654-661. 10.1097/00001648-200111000-00013.

Levy D, Lumley T, Sheppard L, Kaufman J, Checkoway H: Referent selection in case-crossover analyses of acute health effects of air pollution. Epidemiology. 2001, 12: 186-192. 10.1097/00001648-200103000-00010.

Lumley T, Levy D: Bias in the case–crossover design: implications for studies of air pollution. Environmetrics. 2000, 11: 689-704. 10.1002/1099-095X(200011/12)11:6<689::AID-ENV439>3.0.CO;2-N.

Lee JT, Kim H, Schwartz J: Bidirectional case-crossover studies of air pollution: bias from skewed and incomplete waves. Environ Health Perspect. 2000, 108: 1107-1111. 10.1289/ehp.001081107.

Bateson TF, Schwartz J: Control for seasonal variation and time trend in case-crossover studies of acute effects of environmental exposures. Epidemiology. 1999, 10: 539-544. 10.1097/00001648-199909000-00013.

Lu Y, Symons JM, Geyh AS, Zeger SL: An approach to checking case-crossover analyses based on equivalence with time-series methods. Epidemiology. 2008, 19: 169-175. 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181632c24.

Yu W, Mengersen K, Hu W, Guo Y, Pan X, Tong S: Assessing the relationship between global warming and mortality: lag effects of temperature fluctuations by age and mortality categories. Environ Pollut. 2011, 159: 1789-1793. 10.1016/j.envpol.2011.03.039.

Barnett AG, Astrom C: Commentary: what measure of temperature is the best predictor of mortality?. Environ Res. 2012, 118: 149-151.

Goodman PG, Dockery DW, Clancy L: Cause-specific mortality and the extended effects of particulate pollution and temperature exposure. Environ Health Perspect. 2004, 112: 179-185.

Schwartz J: The distributed lag between air pollution and daily deaths. Epidemiology. 2000, 11: 320-326. 10.1097/00001648-200005000-00016.

Payton ME, Greenstone MH, Schenker N: Overlapping confidence intervals or standard error intervals: what do they mean in terms of statistical significance?. J Insect Sci. 2003, 3: 34-

Buckley JP, Samet JM, Richardson DB: Commentary: does air pollution confound studies of temperature?. Epidemiology. 2014, 25: 242-245. 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000051.

Braga AL, Zanobetti A, Schwartz J: The effect of weather on respiratory and cardiovascular deaths in 12 U.S. cities. Environ Health Perspect. 2002, 110: 859-863.

Goldberg MS, Gasparrini A, Armstrong B, Valois MF: The short-term influence of temperature on daily mortality in the temperate climate of Montreal, Canada. Environ Res. 2011, 111: 853-860. 10.1016/j.envres.2011.05.022.

Guo Y, Punnasiri K, Tong S: Effects of temperature on mortality in Chiang Mai city, Thailand: a time series study. Environ Health. 2012, 11: 36-10.1186/1476-069X-11-36.

Carder M, McNamee R, Beverland I, Elton R, Cohen GR, Boyd J, Agius RM: The lagged effect of cold temperature and wind chill on cardiorespiratory mortality in Scotland. Occup Environ Med. 2005, 62: 702-710. 10.1136/oem.2004.016394.

Diaz J, Garcia R, Lopez C, Linares C, Tobias A, Prieto L: Mortality impact of extreme winter temperatures. Int J Biometeorol. 2005, 49: 179-183. 10.1007/s00484-004-0224-4.

Atsumi A, Ueda K, Irie F, Sairenchi T, Iimura K, Watanabe H, Iso H, Ota H, Aonuma K: Relationship between cold temperature and cardiovascular mortality, with assessment of effect modification by individual characteristics: Ibaraki prefectural health study. Circ J. 2013, 77: 1854-1861. 10.1253/circj.CJ-12-0916.

Gemmell I, McLoone P, Boddy FA, Dickinson GJ, Watt GC: Seasonal variation in mortality in Scotland. Int J Epidemiol. 2000, 29: 274-279. 10.1093/ije/29.2.274.

Schwartz J: Who is sensitive to extremes of temperature? A case-only analysis. Epidemiology. 2005, 16: 67-72. 10.1097/01.ede.0000147114.25957.71.

Revich B, Shaposhnikov D: Temperature-induced excess mortality in Moscow, Russia. Int J Biometeorol. 2008, 52: 367-374. 10.1007/s00484-007-0131-6.

Hong YC, Kim H, Oh SY, Lim YH, Kim SY, Yoon HJ, Park M: Association of cold ambient temperature and cardiovascular markers. Sci Total Environ. 2012, 435–436: 74-79.

Schwartz J: Is there harvesting in the association of airborne particles with daily deaths and hospital admissions?. Epidemiology. 2001, 12: 55-61. 10.1097/00001648-200101000-00010.

Schwartz J: Harvesting and long term exposure effects in the relation between air pollution and mortality. Am J Epidemiol. 2000, 151: 440-448. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a010228.

Donaldson GC, Keatinge WR: Early increases in ischaemic heart disease mortality dissociated from and later changes associated with respiratory mortality after cold weather in south east England. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1997, 51: 643-648. 10.1136/jech.51.6.643.

Barnett AG, Dobson AJ, McElduff P, Salomaa V, Kuulasmaa K, Sans S: Cold periods and coronary events: an analysis of populations worldwide. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2005, 59: 551-557. 10.1136/jech.2004.028514.

Cold weather payment. [http://www.nidirect.gov.uk/cold-weather-payment]

Fuel allowance. Department of Social Protection, Ireland. [http://www.welfare.ie/en/Pages/Fuel-Allowance.aspx]

Winter fuel payment. [http://www.nidirect.gov.uk/winter-fuel-payment]

The Marmot Review Team: The Health Impacts of Cold Homes and Fuel Poverty. (accessed December 11, 2013). Friends of the Earth. 2011, 42-[http://www.instituteofhealthequity.org/projects/the-health-impacts-of-cold-homes-and-fuel-poverty]

Winter fuel payments update - Commons Library Standard Note. [http://www.parliament.uk/briefing-papers/SN06019.pdf]

Central Statistics Office, Ireland: Survey on income and living conditions. [http://www.cso.ie/en/media/csoie/releasespublications/documents/silc/2011/elderly040910and11.pdf]

Healy JD: Excess winter mortality in Europe: a cross country analysis identifying key risk factors. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2003, 57: 784-789. 10.1136/jech.57.10.784.

Walker R, Liddell C, McKenzie P, Morris C: Evaluating fuel poverty policy in Northern Ireland using a geographic approach. Energy Policy. 2013, 63: 765-774.

Dubois U: From targeting to implementation: the role of identification of fuel poor households. Energy Policy. 2012, 49: 107-115.

Liddell C, Morris C, McKenzie SJP, Rae G: Measuring and monitoring fuel poverty in the UK: National and regional perspectives. Energy Policy. 2012, 49: 27-32.

Ebi K, Mills D: Winter mortality in a warming climate: a reassessment. WIREs Clim Change. 2012, 4: 203-212.

Kinney PL, Pascal M, Vautard R, Laaid K: Winter mortality in a changing climate: will it go down?. Bull Epidemiolo Hebd. 2012, 12–13: 149-151.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

Conceived, designed and coordinated the study: AZ, PG, SB, HM. Analysed the data: AZ, SB. Assisted with data acquisition: PG, HM. Interpretation of data, results and wrote the paper: AZ, PG, SB, HM. All authors read and approved the final version of this manuscript.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Zeka, A., Browne, S., McAvoy, H. et al. The association of cold weather and all-cause and cause-specific mortality in the island of Ireland between 1984 and 2007. Environ Health 13, 104 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1476-069X-13-104

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1476-069X-13-104