Abstract

Background

Since malaria is one of the foremost public health problems in Iran, a malaria elimination phase has been initiated and application of long-lasting insecticidal nets (LLINs) is an important strategy for control. Success and effectiveness of this community based strategy largely dependent on proper use of LLINs. In this context, to determine the community’s knowledge and practices about malaria and LLINs, a study was conducted in Rudan County, one of the important malaria endemic areas in southeast of Iran.

Methods

In this cross-sectional study, 400 households in four villages were selected by cluster randomly sampling method. Community knowledge and practices about malaria and LLINs including symptoms and transmission of malaria and washing, drying and using of bed nets were investigated using pre-tested structured questionnaires. The data were analysed using SPSS.16 software.

Results

In this study nearly 89% of the respondents knew at least one symptom of malaria and 86.8% considered malaria as an important disease. The majority of respondents (77.8%) believed that malaria transmits through mosquito bite and 72.5% mentioned stagnated water as a potential mosquito breeding place. About 46% of respondents mentioned the community health worker as the main source of their information about malaria. Approximately 44.8% of studied population washed the LLINs once in six months and 92% of them mentioned that they dry the bed nets in direct sunlight. While 94% of households reported they received one or more LLINs by government and 60.8% of respondents mentioned that LLINs were the main protective measure against malaria, only 18.5% of households slept under bed nets the night before the survey, this use rate is lower than the targeted coverage (80%) which is recommended by World Health Organization.

Conclusion

Although, majority of studied population were aware of the symptoms and cause of malaria, a majority had misconceptions about LLINs. Therefore, appropriate educational intervention by trained health workers should be developed for a behaviour change and motivating people to use LLINs which would improve malaria elimination programme.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Malaria is considered to be the most prevalent vector-borne disease worldwide and is currently endemic in 97 countries [1]. The disease is endemic in the southeast of Iran, with two seasonal peaks mainly in spring and autumn. The current strategic approaches to malaria control emphasize prevention through the use of long-lasting insecticidal nets (LLINs), as recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO) [2].

Iran has initiated measures to improve malaria elimination through using larvicides, indoor residual spraying (IRS), LLINs, and early case detection and treatment of malaria. In this regard, Iran is aiming to eliminate Plasmodium falciparum by 2015 and to become malaria-free by 2025 [2, 3]. Since 2008, Iran is receiving a Global Fund grant to develop vector control activities, such as distributing insecticide-treated nets (ITNs) and targeted use of IRS [2, 4]. Adequate knowledge on malaria transmission is essential for effective use of preventive measures. People perceive the direct benefits of bed nets through an observable reduction of mosquito nuisance and malaria episodes, which may motivate them to use bed nets more effectively [5]. Besides assuring access to LLINs, acceptability and compliance with net use are the other critical issues in the success of any ITNs programme [6].

The results of studies in various parts of the world revealed that use of insecticide-treated nets is an effective tool against anopheline mosquitoes and reduces morbidity and mortality due to malaria [7, 8]. Treated bed nets have an influential impact on mosquito density and sporozoite rates. However, effectiveness of bed net use is dependent on attitudes and socio- cultural context of population [9]. A high coverage of long- lasting insecticidal nets followed by educational intervention, results in a decrease in malaria morbidity and reduces transmission, as showed in a study from rural area in southeast of Iran [10]. A recent study on malaria knowledge in Iran indicated that populations’ educational level is positively associated with knowledge of malaria transmission, aetiology and clinical symptoms of the disease [11].

Rudan is a malarious area with local transmission in the southeast of Iran. In this county, 63 cases of malaria were reported during 2009–2013. The parasite species composition was 91% Plasmodium vivax and 9% Plasmodium falciparum (Hormozgan Health Centre, unpublished data, 2014). Previous studies have reported four malaria vectors in this area including: Anopheles culicifacies s.l., Anopheles dthali, Anopheles stephensi and Anopheles superpictus where, An. stephensi is primary vector and other species play role as secondary vectors [12].

Indoor residual spraying and distribution of long-lasting insecticide-treated nets have been the main vector control measures implemented as part of an integrated approach to malaria elimination in this county [12]. In addition to achieve sufficient LLINs coverage, a challenge is identifying and addressing the behavioural factors that influence LLINs use. Understanding the community knowledge about malaria and LLINs would help in designing sustainable malaria control programmes that will lead to behavioural change and adoption of new ideas [13]. The participation of the community is one of the major tools of malaria elimination programmes and improved community knowledge of malaria and its transmission can promote preventive and personal protective practices amongst the target populations [14]. Parallel to implementation of malaria elimination in Iran, this study was conducted to determine the community knowledge and practice regarding malaria and its preventive measures, with an emphasis on the use of LLINs in Rudan County, southeast of Iran.

Methods

Study area

The study was carried out in Rudan county of Hormozgan province, one of the malaria endemic areas in southeastern Iran. The county is located between 27°05′- 27°59′ N latitudes and 56°50′ - 57° 29′ E longitudes with an estimated population of 118,547 individuals in 2011. The annual mean relative humidity is 54% and the average of annual rainfall is about 250 mm. The average daily temperature ranges from 9°C to 45°C. In the study area nearly all of houses are made of cement blocks and have electricity and water supply. The main economic activities in the area are agricultural with palm and citrus plantation and livestock herding. Malaria transmission in the area is endemic which occurs year-round with peaks after the two annual rainy seasons (April-June and October -December) [3].

Study design and data collection

The study was a community-based cross-sectional survey conducted between May and July, 2013 in Rudan County, where LLINs had been previously distributed for malaria elimination.

Assuming expected knowledge about malaria and LLINs to be 50% and a desired precision of 5%, the sample size calculated by the formula to be 400. Study villages were selected by a two-stage randomized cluster sampling procedure. In the first stage, four villages with similar topographical and epidemiological situations were selected randomly. In the second stage, 100 households were randomly selected for each village. As the father of family is mostly out of house to work, mothers of randomly selected households were interviewed using a pre-tested, structured questionnaire (see Additional file 1). In case they were absent, the daughter of household or another adult member was interviewed instead. The questionnaires were administered by trained field interviewers and supervised by the principal investigator. The questions included respondents’ demographic characteristics, knowledge (five items) and practices (10 items) about malaria and LLINs including malaria symptoms and transmission and washing, drying, and using of bed nets.

Interviewers verified the bed net usage during last night by checking whether the net was hanging over sleeping place or folded during the home visit in the morning hours. The answers about dwelling houses construction materials, windows, and water containers were confirmed during the investigators visit of each household. In addition, socio-economic factors which could predispose communities to malaria transmissions were investigated.

Statistical analysis

The data were analysed using SPSS version 16. Descriptive statistics were used to measure percentages, averages, and relative frequencies of the variables. Cross tabulations of variables were done and Chi-squared test (χ2) was used to determine the statistical significance of differences of relative frequencies. The results were considered significant at 5% levels of significance (p < 0.05). The knowledge and practice regarding malaria and LLINs were compared with the educational status of the respondents. Correlation coefficients were calculated for the knowledge regarding malaria, LLINs and the reported practices.

Ethical consideration

Households of study villages were informed about the objectives and procedures of the investigation. The respondents were informed that their participation was purely voluntary and they were free to withdraw from the study at any time. Study identification numbers were used instead of participant names and collected data were kept confidential.

Results

Characteristics of the study population

A total of 400 households were interviewed. The ages of respondents ranged from 17 to 75 years with an average of 37.07 years. The mean family size was 4.9 people ranging from 1 to 11 people. About one third of the women had completed primary school education (32.3%) and 37.3% had not attended any formal education. Most of the respondents (92.7%) were unemployed and engaged in housework; others were self-employed, farmer/stockbreeder, students, and in other services. Socio-demographic Characteristics of the study population is shown in Table 1. The majority of households had a home constructed of cement blocks (96.7%) and 14.5% of houses had screens over the window openings (Table 2). Most of the study population had access to clean piped water (96.5%) and electricity (98.0%) in their houses. About half of houses (49.2%) were built within 20 metres of domestic animal shelters (Table 2).

Malaria knowledge and practices

The majority of study population (86.8%) had knowledge about malaria as a disease and 77.8% of them believed that malaria is transmitted through the bite of mosquitoes and this was significantly associated with their educational level (X2 = 3.84, df = 4, P = 0.038) (Table 3). Even though a majority of respondents were aware of the cause of malaria, 8% didn’t know the actual cause of malaria and 14.2% had misconceptions, such as drinking dirty water, eating contaminated food and inhaling polluted air as the cause of malaria transmission (Table 3).

Fever and chills were the two most frequently mentioned signs and symptoms of malaria, although participants also identified bone pain and abdominal discomfort as other symptoms of the disease (Table 3).

Nearly 10% of participants reported having cases of malaria infection in their family within the past 3 years (Table 3). The households who had previously been infected with malaria in their family showed better knowledge of malaria symptoms than those with no history of malaria infection (X2 = 8.32, df = 6, P = 0.02). Most of the respondents (72.5%) considered stagnated water as breeding place of mosquitoes.

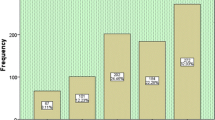

Generally, community knowledge regarding malaria prevention was high (98%) and most of households (60.8%) mentioned the use of LLINs as a preventive measure against malaria. Other mentioned measures against malaria included indoor residual spraying (15%), screen on doors/windows (14.5%) and chemoprophylaxis (4.5%) (Table 3).The community health workers were the most prominent source of malaria information (46%) and media, i.e., television and radio were the second most mentioned sources of information (36.7%). In addition, some of participants received malaria information from religious leaders in community meetings. Newspapers and books were the least often heard messages (Figure 1).

This study results also showed that about half of the respondents (51%) were interested in participating in malaria control programme as a volunteer (Table 3). A significant relationship was found between the educational levels of respondents and their interest in participating in malaria control programmes as a volunteer (X 2 = 12.18, df = 6, P = 0.014).

Knowledge and practice regarding LLINs

Out of 400 studied households 376 (94%) reported they received one or more LLINs by government. The majority of households (76.8%) reported that they use LLINs. However, regular use of LLINs was 18.5% as it was checked visually in the morning hours by interviewers (Table 4). Analysis of factors influencing regular use of bed nets showed that bed net use rate was positively associated with educational level of respondents (X2 = 6.82, df = 2, P = 0.001).

Most of the studied population (82.5%) reported that all of family members sleep under bed nets and 17.5% of respondents mentioned that only parents (9.5%) or children (8%) use bed nets. There was no association between using bed nets and reporting cases of a malaria infection in the family in the past year (X 2 = 3.26, P = O.812).

The results also showed that 43.5% of households use the bed nets all the time at night and 56.5% of them over the sleeping time (Table 3). Protection against mosquito bites and malaria transmission was reported to be the main reason for using LLINs (84%). The other reasons were having an undisturbed night sleep with protection from other insects’ nuisance (8.5%) and protection from scorpion stings (5.5%).

In this study, approximately 87% of households reported they did not receive instructions on washing and drying the bed nets at the time of LLINs distribution. The results also showed that 44.8% of studied population wash the LLINs once in six months. Moreover, the majority of respondents (92%) mentioned that they dry the washed LLINs in direct sunlight because it is a usual practice for drying wet cloths. Details of net washing and drying practices are shown in Table 4.

Discussion

This study was conducted to provide baseline information on knowledge and practices regarding malaria and LLINs, which can be used in the development of a plan for community participation towards the prevention and control of malaria. This study indicated that the knowledge of studied population about malaria transmission and symptoms is high. This finding is supported by other studies in the southeast of Iran [11]. Similarly, in studies conducted in Ghana, Malaysia, Tanzania, Guinea-Bissau, Mali and Uganda high awareness of people about malaria was reported [13–19].

According to the results, the most important sources of information were health centres. This finding illustrates that health workers are frequently in contact with villagers. It has been previously reported that access to health centres and communication facilities plays an important role in prevention and control of malaria [19].

This study also showed a positive relationship between knowledge of the respondents about malaria symptoms and the past history of malaria infection in the family. It is a common observation in endemic area where people suffer frequently from malaria infection [20–22].

In this study, majority of the people knew that mosquito bite can cause malaria. High level of knowledge about malaria transmission route in the studied population may be due to long-term exposure to malaria over years. In contrast to these findings, in other communities only those with a higher level of education knew the vector and symptoms of malaria [14, 23].

An important finding of this study was that majority of the households knew stagnated water as breeding place of mosquitoes. This finding is in agreement with a previous study conducted in Bashagard county, adjacent to the study area, which revealed high knowledge of people about mosquito breeding places [10]. Similar findings have been reported from malaria endemic countries such as Tanzania, Nepal and India [20, 24, 25]. High awareness of mosquitoes breeding places could influence several factors involved in the vector control, such as the selection of residential areas and use of preventive measures aiming to reduce mosquito population density.

According to the results, although 77.8% of the studied population mentioned mosquitoes as the vector of malaria and 60.8% reported LLINs as the preventive measure against malaria transmission, LLINs were used by only 18.5% when interviewers checked bed nets use visually in the morning hours. A reason for this may be low perceived susceptibility of households about malaria infection; in other words, they don’t see themselves exposed to malaria infection. Another reason can be their low perceived severity of malaria infection. A comparable observation has been made in rural community of western Kenya [26]. Our results are also similar to findings of Tsuyuoka et al. in Zimbabwe, where 6- 24% of children under five years and 2.8 - 9.7% pregnant women used [27].

An LLIN use rate of 18.5%, as found in this study, is thus considerably lower than 80% which is the targeted coverage of the Roll Back Malaria [28]. Moreover, this is much lower than LLINs use rate in other malaria endemic countries, such as India (79.2%), Sierra Leone (67.2%), and Sri Lanka (90%) [6, 29, 30]. Moreover, 56.5% of households reported they use bed nets only during sleeping time. Considering that malaria transmission occurs during 10 months in the study area and some of malaria vectors prefer to bite mainly outdoors in the earlier times of night [4, 12, 31], peoples who spend earlier times of night outside may be bitten more frequently and have more chance to get malaria. There were several reports confirming that regular use of insecticide-treated nets increase when individuals receive information about bed nets [8, 13]. In a recent study conducted in a malarious area of Iran, regular use of LLINs increased from 58.3% to 92.5% following educational intervention [10]. Therefore, effective educational programmes may increase use of LLINs in the studied population.

According to the results about half of households washed their LLINs once in six months which is according to the manufacturer’s maintenance instructions [8]. They had not received manufacturer’s washing instructions and the main reason for washing frequency was that they became dirty. Similar findings have been reported from malaria endemic areas of the Sri Lanka [32]. Hence, required washing frequency of bed nets should be instructed to the studied population during an educational intervention.

Previous study in the southeast of Iran reported that washing frequency of once in six months increased from 37.6% to 68.9% following educational intervention. Every six months washing is required to maintain the long-lasting efficacy of LLINs and more frequent washing decreases the efficacy because large proportion of the insecticide is removed during the washing process [32].

According to manufacturer’s instructions bed nets should be dried in shade, However drying in black vinyl bags under direct sunlight is also recommended to improve regeneration of insecticides on the surface of bed nets which is needed for repelling mosquitoes [8, 32].

This study indicated that majority of household dried the Olyset® nets under direct sunlight. Drying the LLINs under direct sunlight is not recommended by manufacturers and should be avoided because it diminishes the biological efficacy of the bed nets.

Based on the findings of this study households in the studied area should be trained on correct procedure of washing and drying of LLINs according to manufacturer’s instructions to protect the potency of LLINs over the time.

Conclusion

This study highlighted the discrepancy between knowledge about transmission and symptoms of malaria and use of bed nets as a preventive measure. This difference between knowledge and practice is probably due to the fact that although the individual’s knowledge about malaria is high, it has not promoted their attitude towards using the bed nets. Therefore, educational intervention aiming to change the attitude and practice of people is a key element for malarial control in the studied population. In this context mass distribution of LLINs accompanied with education for behaviour change may improve the use of bed nets. Standardized verbal and written education should include information on the regular use and instructions on washing and drying of bed nets, which would improve malaria elimination programme in Iran. Moreover, continuous monitoring and evaluation of LLINs effectiveness is recommended for successful and sustainable malaria elimination programme.

References

WHO: World Malaria Report. 2013, Geneva: World Health Organization, [Available at: http://www.who.int/malaria/publications/world_malaria_report_2013/en/]

WHO: World Malaria Report. 2011, Geneva: World Health Organization, [Available at: http://www.who.int/malaria/world_malaria_report_2011/en/index.html]

Hemami MR, Sari AA, Raeisi A, Vatandoost H, Majdzadeh R: Malaria elimination in iran, importance and challenges. Int J Prev Med. 2013, 4: 88-94.

Soleimani-Ahmadi M, Vatandoost H, Shaeghi M, Raeisi A, Abedi F, Eshraghian MR, Madani A, Safari R, Oshaghi MA, Abtahi M, Hajjaran H: Field evaluation of permethrin long-lasting insecticide treated nets (Olyset®) for malaria control in an endemic area, southeast of Iran. Acta Trop. 2012, 123: 146-153. 10.1016/j.actatropica.2012.04.004.

Toe LP, Skovmand O, Dabire KR, Diabate A, Diallo Y, Guiguemde TR, Doannio JM, Akogbeto M, Baldet T, Gruenais ME: Decreased motivation in the use of insecticide-treated nets in a malaria endemic area in Burkina Faso. Malar J. 2009, 8: 175-10.1186/1475-2875-8-175.

Gunasekaran K, Sahu SS, Vijayakumar KN, Jambulingam P: Acceptability, willing to purchase and use long lasting insecticide treated mosquito nets in Orissa State, India. Acta Trop. 2009, 112: 149-155. 10.1016/j.actatropica.2009.07.013.

Sharma SK, Upadhyay AK, Haque MA, Padhan K, Tyagi PK, Batra CP, Adak T, Dash AP, Subbarao SK: Effectiveness of mosquito nets treated with a tablet formulation of deltamethrin for malaria control in a hyperendemic tribal area of Sundargarh District, Orissa, India. J Am Mosq Control Assoc. 2006, 22: 111-118. 10.2987/8756-971X(2006)22[111:EOMNTW]2.0.CO;2.

Hill J, Lines J, Rowland M: Insecticide-treated nets. Adv Parasitol. 2006, 61: 77-128.

Atkinson JA1, Bobogare A, Fitzgerald L, Boaz L, Appleyard B, Toaliu H, Vallely A: A qualitative study on the acceptability and preference of three types of long-lasting insecticide-treated bed nets in Solomon Islands: implications for malaria elimination. Malar J. 2009, 8: 119-10.1186/1475-2875-8-119.

Soleimani Ahmadi M, Vatandoost H, Shaeghi M, Raeisi A, Abedi F, Eshraghian MR, Aghamolaei T, Madani AH, Safari R, Jamshidi M, Alimorad A: Effects of educational intervention on long-lasting insecticidal nets use in a malarious area, southeast Iran. Acta Med Iran. 2012, 50: 279-287.

Hanafi-Bojd AA, Vatandoost H, Oshaghi MA, Eshraghian MR, Haghdoost AA, Abedi F, Zamani G, Sedaghat MM, Rashidian A, Madani AH, Raeisi A: Knowledge, attitudes and practices regarding malaria control in an endemic area of southern Iran. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 2011, 42: 491-501.

Soleimani-Ahmadi M, Vatandoost H, Hanafi-Bojd AA, Zare M, Safari R, Mojahedi A, Poorahmad-Garbandi F: Environmental characteristics of anopheline mosquito larval habitats in a malaria endemic area in Iran. Asian Pac J Trop Med. 2013, 6: 510-515. 10.1016/S1995-7645(13)60087-5.

Adongo PB, Kirkwood B, Kendall C: How local community knowledge about malaria affects insecticide-treated net use in northern Ghana. Trop Med Int Health. 2005, 10: 366-378. 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2005.01361.x.

Al-Adhroey AH, Nor ZM, Al-Mekhlafi HM, Mahmud R: Opportunities and obstacles to the elimination of malaria from Peninsular Malaysia: knowledge, attitudes and practices on malaria among aboriginal and rural communities. Malar J. 2010, 9: 137-10.1186/1475-2875-9-137.

Mashauri FM, Kinung’hi SM, Kaatano GM, Magesa SM, Kishamawe C, Mwanga JR, Nnko SE, Malima RC, Mero CN, Mboera LE: Knowledge, attitudes and practices about malaria among communities: comparing epidemic and non-epidemic prone communities of Muleba district, North-western Tanzania. BMC Public Health. 2010, 10: 395-10.1186/1471-2458-10-395.

King R, Mann V, Boone PD: Knowledge and reported practices of men and women on maternal and child health in rural Guinea Bissau: a cross sectional survey. BMC Public Health. 2010, 10: 319-10.1186/1471-2458-10-319.

Mahamadou AT, D’Alessandro U, Thiéro M, Ouedraogo A, Packou J, Souleymane OAD, Fané M, Ade G, Alvez F, Doumbo O: Child malaria treatment practices among mothers in the district of Yanfolilo, Sikasso region, Mali. Trop Med Int Health. 2000, 5: 876-881. 10.1046/j.1365-3156.2000.00652.x.

Nsungwa-Sabiiti J, Kallander K, Nsabagasani X, Namusisi K, Pariyo G, Johansson A, Tomson G, Peterson S: Local fever illness classifications: implications for home management of malaria strategies. Trop Med Int Health. 2004, 9: 1191-1199. 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2004.01319.x.

Faye O, Correa J, Camara B, Dieng T, Dieng Y, Gaye O, Bah IB, N’Dir O, Fall M, Diallo S: Malaria lethality in Dakar pediatric environment: study of risk factors. Med Trop. 1998, 58: 361-364.

Mazigo HD, Obasy E, Mauka W, Manyiri P, Zinga M, Kweka EJ, Mnyone LL, Heukelbach J: Knowledge, attitudes, and practices about malaria and its control in rural Northwest Tanzania. Malar Res Treat. 2010, 2010: 794261-

Ahmed SM, Haque R, Haque U, Hossain A: Knowledge on the transmission, prevention and treatment of malaria among two endemic populations of Bangladesh and their health-seeking behaviour. Malar J. 2009, 8: 173-10.1186/1475-2875-8-173.

Adam I, Omer ESM, Salih A, Khamis AH, Malik EM: Perceptions of the causes of malaria and of its complications, treatment and prevention among midwives and pregnant women of Eastern Sudan. J Public Health. 2008, 16: 129-132. 10.1007/s10389-007-0124-2.

Ager A: Perception of risk for malaria and schistosomiasis in rural Malawi. Trop Med Parasitol. 1992, 43: 234-238.

Joshi AB, Banjara MR: Malaria related knowledge, practices and behaviour of people in Nepal. J Vector Borne Dis. 2008, 45: 44-50.

Tyagi P, Roy A, Malhotra MS: Knowledge, awareness and practices towards malaria in communities of rural, semi-rural and bordering areas of east Delhi (India). J Vector Borne Dis. 2005, 42: 30-35.

Karanja DM, Alaii J, Abok K, Adungo NI, Githeko AK, Seroney I, Vulule JM, Odada P, Oloo JA: Knowledge and attitudes to malaria control and acceptability of permethrin impregnated sisal curtains. East Afr Med J. 1999, 76: 42-46.

Tsuyuoka R, Midzi SM, Dziva P, Makunike B: The acceptability of insecticide treated mosquito nets among community members in Zimbabwe. Cent Afr J Med. 2002, 48: 87-91.

WHO: The Global Strategic Plan 2005- 2015- Roll Back Malaria. 2010, Geneva: World Health Organization

Gerstl S, Dunkley S, Mukhtar A, Maes P, De Smet M, Baker S, Maikere J: Long-lasting insecticide-treated net usage in eastern Sierra Leone -the success of free distribution. Trop Med Int Health. 2010, 15: 480-488.

Fernando SD, Abeyasinghe RR, Galappaththy GN, Gunawardena N, Ranasinghe AC, Rajapaksa LC: Sleeping arrangements under long-lasting impregnated mosquito nets: differences during low and high malaria transmission seasons. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2009, 103: 1204-1210. 10.1016/j.trstmh.2008.10.018.

Soleimani-Ahmadi M1, Vatandoost H, Shaeghi M, Raeisi A, Abedi F, Eshraghian MR, Madani A, Safari R, Shahi M, Mojahedi A, Poorahmad-Garbandi F: Vector ecology and susceptibility in a malaria-endemic focus in southern Islamic Republic of Iran. East Mediterr Health J. 2012, 18: 1034-1041.

Fernando SD, Abeyasinghe RR, Galappaththy GN, Gunawardena N, Rajapakse LC: Community factors affecting long-lasting impregnated mosquito net use for malaria control in Sri Lanka. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 2008, 102: 1081-1088. 10.1016/j.trstmh.2008.06.007.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to appreciate the collaboration received from Dr. Badraddin, Head of Rudan Health Center for providing facilities for implementation of this investigation. We especially thank Mr. H. Firozi, Mr. A. Jafari, Mr. R. Shahi-Zahi, Mr. F. Mahmudi, Mr. M. Abbaszadeh, Mr. A. Kamali, Mr. M. Zarei and Mr. A. Haddadi personnel of the Rudan Health Center, for their cooperation in the field. We are also grateful to Dr. Madani, Head of Hormozgan Health Center for his logistic support in collected samples. This study received financial support from Research Deputy of Hormozgan University of Medical Sciences (Project No.397).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

MSA designed the study, coordinated field activity, collected data, trained field researcher and drafted the manuscript. HV designed the study and revised the manuscript. MZ drafted the manuscript. AA participated in the conception of study design. The field research activities were supported by MS. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

12936_2014_3668_MOESM1_ESM.docx

Additional file 1: Survey questionnaire for community knowledge and practices regarding malaria and long-lasting insecticidal nets in an endemic area in Iran.(DOCX 13 KB)

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Soleimani-Ahmadi, M., Vatandoost, H., Zare, M. et al. Community knowledge and practices regarding malaria and long-lasting insecticidal nets during malaria elimination programme in an endemic area in Iran. Malar J 13, 511 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2875-13-511

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1475-2875-13-511