Abstract

Background

Systematic attempts to identify best practices for reducing hospital readmissions have been limited without a comprehensive framework for categorizing prior interventions. Our research aim was to categorize prior interventions to reduce hospital readmissions using the ten domains of the Ideal Transition of Care (ITC) framework, to evaluate which domains have been targeted in prior interventions and then examine the effect intervening on these domains had on reducing readmissions.

Methods

Review of literature and secondary analysis of outcomes based on categorization of English-language reports published between January 1975 and October 2013 into the ITC framework.

Results

66 articles were included. Prior interventions addressed an average of 3.5 of 10 domains; 41% demonstrated statistically significant reductions in readmissions. The most common domains addressed focused on monitoring patients after discharge, patient education, and care coordination. Domains targeting improved communication with outpatient providers, provision of advanced care planning, and ensuring medication safety were rarely included. Increasing the number of domains included in a given intervention significantly increased success in reducing readmissions, even when adjusting for quality, duration, and size (OR per domain, 1.5, 95% CI 1.1 - 2.0). The individual domains most associated with reducing readmissions were Monitoring and Managing Symptoms after Discharge (OR 8.5, 1.8 - 41.1), Enlisting Help of Social and Community Supports (OR 4.0, 1.3 - 12.6), and Educating Patients to Promote Self-Management (OR 3.3, 1.1 - 10.0).

Conclusions

Interventions to reduce hospital readmissions are frequently unsuccessful; most target few domains within the ITC framework. The ITC may provide a useful framework to consider when developing readmission interventions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Unsafe transitions of care from the hospital to the community are common and are frequently associated with post-discharge adverse events, including hospital readmission [1]. While not all hospital readmissions are preventable, the volume of patients readmitted (nearly one in five Medicare patients by 30 days post-discharge) and costs associated with readmissions ($26-44 billion per year spent by Medicare) make remediating unsafe transitions essential [2].

However, best practices to cost-effectively reduce readmissions are not well-elucidated [3]. A previous systematic review of interventions to reduce hospital readmissions did not identify an intervention or bundle of interventions that reliably reduced readmissions, despite well-conducted individual trials that have reduced readmission rates [4]. In that review, the authors constructed a simple temporal taxonomy to categorize interventions into pre-discharge, post-discharge, and “bridging” interventions. We hypothesize that a taxonomy focused on individual activities that lead to safer transitions of care may provide new insights into why some interventions are successful and many others are not.

The Ideal Transition of Care (ITC) framework (Additional file 1: Figure S1) proposes 10 domains to consider in ensuring safe transitions of care, based upon expert guidelines, critical analysis of the literature, and clinical experience [5]. The ITC has been proposed as a method for analyzing failures and guiding new interventions in transitions of care, as well as creating process measures to monitor the quality of care transitions.

We had four related research aims in this study: 1) to establish how frequently each of the ten ITC domains have been utilized in prior interventions; 2) to discover how frequently prior interventions met with success in reducing readmissions; 3) to examine the relationship between each of the ten ITC domains individually with success in reducing readmissions; and 4) to evaluate the relationship between the total number of ITC domains included in an intervention and successful readmission reduction. Thus, we conducted a comprehensive review of the literature to identify prior interventions intended to reduce hospital readmission, and categorized them according to the ten ITC domains for our secondary analysis.

Methods

Review of the literature

We conducted a search of MEDLINE, EMBASE, Web of Science, and the Cochrane Library for English-language reports published between January 1975 and October 2013 looking for prospective interventions to reduce readmissions (Additional file 1: Figure S1). The MEDLINE search was carried out in a similar way to a prior systematic review [4], using the following combinations of Medical subject Heading (MeSH) keywords: (“Hospitalization” [Mesh] OR “Patient Discharge [Mesh] OR “Patient Readmission” [Mesh] OR readmission [All Fields] or post discharge [All Fields] OR postdischarge [All Fields] or intervention [All Fields]) AND (“Continuity of Patient Care” [Mesh] OR transition* [All Fields] or coordination [All Fields] OR (“patient readmission” [Mesh] AND “patient discharge” [Mesh]) OR (rehospitali* [title] OR readmi* [title]). We reviewed reference lists of studies we selected for full-text review to identify any additional studies.

Studies were included for full-text review if the abstract indicated the primary objective of the study was to prospectively evaluate the efficacy of a given intervention to reduce readmission rates in an intervention cohort, compared to a nonintervention cohort. We included both interventions for patients with specific disease states and those targeting all discharged patients regardless of disease state. We elected to include studies with endpoints longer than thirty days as many of the domains in the ITC could be delivered over longer time periods and our intent was to evaluate their efficacy overall when included in an intervention, rather than at a single time point. Randomized controlled trials and observational designs were eligible for inclusion.

We excluded retrospective studies, interventions using disease-specific interventions to readmission reduction (such as measurement of brain natriuretic peptide as a method to reduce readmissions in congestive heart failure), or interventions consisting solely of medication titration (such as increasing the dose of an ACE inhibitor in heart failure patients and measuring rehospitalizations as an outcome). Interventions were eligible for inclusion if a disease-specific population was studied but an intervention that was applicable to other disease states was used. We also excluded studies of exclusively pediatric, obstetric, surgical, or psychiatric populations (if the primary focus was on psychiatric readmissions). In cases of multiple reports of the same study or intervention, the earliest publication reporting results of the intervention (if not a pilot study) was used. Two reviewers (Dr. Burke and Dr. Misky) screened all abstracts, and retained relevant articles for full-text review. We included studies for full-text review when the abstract did not clearly indicate whether the inclusion criteria were met.

The full text of selected articles was independently reviewed by two reviewers for inclusion and exclusion criteria, and the final list of included articles was reached through discussion and consensus. Studies in which we were unable to identify which domains were targeted were excluded at this stage. Our final cohort of studies included 39 studies from a prior systematic review [4], as well as 27 new studies not included in this review (Figure 1).

Categorizing into ITC domains

The two reviewers first met to discuss the Ideal Transition of Care framework and review the salient features within each domain. Then, their assessments of the domains included in several papers excluded from the final analysis were compared to identify areas of disagreement and resolve differences. Each intervention included in our final analysis was then independently read by each reviewer in detail to assess and record which of the 10 domains of the Ideal Transition of Care were included in the intervention (graded as present or absent). In case of disagreement between reviewers about whether a domain was included in a particular study, we counted the domain as present if at least one of the reviewers marked it present (Table 1).

Intervention size, quality, and duration were recorded by each reviewer. Intervention size was recorded as the size of the total study cohort (including both intervention and control groups) and is reported as a median given distribution of study size. Quality was categorized on a three-point scale, with randomized, prospective trials as the highest-quality category, prospective cohort studies next, and before-after designs as the lowest quality. We found the Cochrane Effective Practice and Organization of Care (EPOC) Group’s Risk of Bias criteria [72] difficult to assess given the limited data provided in previous included publications; this assessment did not contribute significantly to prior analysis of these studies [4]. Duration was recorded as the time point at which the authors reported the study’s primary outcome.

Analysis of ITC domains

This is a secondary analysis of the publications included above. Success in reducing readmissions was defined as a binary outcome determined by whether there was a statistically significant reduction in readmissions in the intervention group compared to the control group in each of the selected studies. Effect size was not chosen as the outcome for two reasons: first, it was not always reported (for interventions reporting readmissions as a composite outcome, group-specific rates of readmissions were sometimes not reported), and second, we were concerned about the possibility of smaller studies (with large confidence intervals around effect size) unduly influencing our results, where statistically significant reductions in readmissions biases towards larger studies with more power. Bivariate associations between the presence of each of the 10 domains and success in reducing readmissions were examined using Chi-Square tests or Fisher’s exact test if there were small cell counts (<5). The resulting p-values were adjusted for multiple comparisons using a False Discovery Rate (FDR) correction. All comparisons were two-tailed and FDR-adjusted p-values of less than 0.05 were considered to be significant. Unadjusted odds ratios (OR) and their 95% confidence intervals (CI) were also calculated using simple logistic regression.

Simple logistic regression was used to study the crude association between the total number of domains included in an intervention and success in reducing readmissions. We also used multiple logistic regression to study the adjusted association between the total number of domains included and success in reducing readmissions, adjusting for study size, quality, and duration. ORs and their 95% CIs were calculated. All statistical analyses were performed using R 3.0.2 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). The study was considered exempt by the Colorado Multiple IRB (COMIRB). This study was reviewed and deemed exempt by the Colorado Multiple IRB (COMIRB).

Results

After application of inclusion and exclusion criteria, 66 articles were included in the final analysis (Additional file 2: Table S1). Median study size was 283 patients (interquartile range, 270). Thirty-five studies (53%) evaluated the primary endpoint at 30 or fewer days following hospital discharge; results of our statistical analyses were similar when comparing studies with primary endpoints of 30 or fewer days with those having endpoints greater than 30 days and thus all studies were analyzed as a single group. Interventions directed at all discharging patients accounted for 52% of included studies, while 41% were studies of heart failure patients exclusively. Overall, 42% of studies demonstrated a statistically significant reduction in readmissions between the intervention and control groups; 61% of these were studies of specific disease processes rather than all discharging patients.Prior interventions addressed 3.5 domains on average; only 23% addressed five or more (Figure 2). Monitoring and Managing Symptoms after Discharge (included as part of 74% of interventions), Educating Patients to Promote Self-Management (64%), and Coordinating Care among Team Members (55%) were the domains most frequently included as a part of the intervention. Conversely, Advance Care Planning was not included as a part of an intervention in any study, while the two domains concerning information transfer to receiving clinicians and the Medication Safety domain were rarely included (<20%, Figure 3).

ITC domains addressed across interventions. Legend: The percent of interventions that included a particular domain of the ITC framework is shown. MM = Monitoring and Managing Symptoms After Discharge; EP = Patient Education to Promote Self-Management; CCA = Coordinating Care Among Team Members; DP = Discharge Planning, FO = Outpatient Follow-Up; EH = Enlisting Help of Social and Community Supports; MS = Medication Safety; AT = Accuracy, Timeliness, Clarity, and Organization of Information; CCI = Complete Communication of Information; AP = Advance Care Planning.

In bivariate analysis, the Monitoring and Managing Symptoms after Discharge domain was significantly associated with success in reducing readmissions (OR 8.5 (95% CI 1.8 - 41.1), FDR-corrected p-value = 0.03). Two other domains, Enlisting Help of Social and Community Supports (OR 4.0 (1.3-12.6), FDR-corrected p = 0.07) and Educating Patients to Support Self-Management (OR 3.3 (1.1-10.0), FDR-corrected p = 0.09) showed relatively strong associations with reductions in readmissions (Table 2).

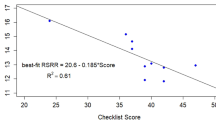

The number of domains included in an intervention was significantly associated with success in reducing readmissions, even after adjusting for study quality, duration, and size (OR per domain included 1.5, 95% CI 1.1-2.0).

Discussion

The most important finding of our study for physicians charged with reducing readmissions is that increasing the number of targeted domains within the ITC was associated with significantly increased success in reducing readmissions. In addition, not all domains were associated with equal effect in reducing readmissions. Among the individual domains, systems for Monitoring and Managing Symptoms after Discharge were most associated with successful reduction in readmissions, while Enlisting Help of Social and Community Supports, and Educating Patients to Promote Self-Management may also be efficacious.

Categorizing prior studies in the ITC framework offered important insights into the “state of the science” of readmission reduction. We found most interventions targeting a reduction in hospital readmission published in the literature have not been successful. The 41% overall success rate of published interventions most likely reflects the fact that patients discharged from acute care settings exhibit multiple risk factors for readmission spanning the 10 domains of the Ideal Transition of Care. Since most interventions published targeted a few, similar domains, a correspondingly low success rate of an individual intervention may not be surprising, though our study design limits causal inference. While the ten domains of the ITC framework center on modifiable risk factors for admission, we did not assess how “preventable” readmissions were in included studies.

To the individual clinician, implementing these findings may seem daunting. However, effective multi-domain models exist [8, 14, 18, 39] and nearly all provide options for substantial training. A recurring characteristic of these models is provision of a single health care provider responsive to multiple patient needs, thereby targeting multiple domains of the Ideal Transition of Care. Jack et al. used a “discharge advocate” to provide intensive patient-centered education, discharge planning and post-discharge reinforcement [14]. Likewise, Coleman et al. implemented a “transition coach” to assist patients across health settings and encouraged patients to be active in their own care, while providing them the necessary tools to do so [8]. Similarly, Naylor et al. used an advance practice nurse to manage an individualized patient plan tailored to identified needs, with a focus on patient education and longitudinal collaboration of key providers from hospital admission through two weeks post-discharge [18]. Peikes et al. found success in local care coordination, effectively targeting multiple risk factors for readmission for enrolled patients, and changed their intervention from one that increased readmissions and cost to one that reduced both [39].

However, these models require substantial investment of resources. Clinicians and health care systems with limited resources (particularly those already penalized financially for elevated readmission rates) may struggle to implement these interventions. A key finding from our study is that one option for limiting costs- limiting the number of domains targeted- may not lead to success. A method to risk-stratify patients at the time of discharge, then selectively apply interventions based on this analysis, may maximize efficacy and minimize cost. [3] However, currently available risk prediction models lack accuracy and capture only a global assessment of risk that is difficult to apply to individual patients across highly variable delivery systems. [73] Frameworks similar to the ITC framework may hold promise as tools to better assess individual, modifiable risk factors for readmission of recently hospitalized patients, and design interventions to address these risk factors on a case-by-case basis in order to provide tailored, risk-stratified care.

Three domains within the ITC were most associated with success in reducing readmissions. Monitoring and Managing Symptoms after Discharge is plausible as an individual domain most strongly associated with success in reducing readmissions given post-discharge adverse events are common and frequently present with new symptoms. [1] Thus, close clinical monitoring of a recently discharged patient for active symptoms helps ensure effective post-hospital care. Home visits by health care professionals (rather than telemonitoring) appear to be a common theme in several successful interventions [8, 18, 40, 42].

Despite inclusion in fewer than one in four existing interventions, active integration of community and social support networks addressing needs of patients was also associated with success in reducing readmissions. Indeed, this is the intent of Medicare’s $500 million Community-Based Care Transitions Project, part of the Partnership for Patients instituted by the Affordable Care Act. A discharge planning protocol conducted by a social worker to assess living environment and social supports, then engaging community and social service referrals as needed, was the cornerstone of a successful intervention by Evans et al. [11] Several other successful interventions also addressed community supports as a component of a larger intervention [39, 40, 42], indicating the need to address this specific element of a patient’s care transition.

Patient education to promote active involvement in their own care has been a much more commonly targeted domain, though few interventions have assessed the efficacy of this education. Coleman’s transition coach taught patients how to self-manage and to interact with the health care system; benefits were found months after the intervention had concluded [8]. Providing patient education in isolation from other elements and without active patient involvement is likely insufficient to reduce readmissions [13]. Rather, successful interventions focus on engaging the patient to manage their chronic illnesses in an ongoing manner.

These results should be interpreted in the context of the literature reviewed. None of the interventions we reviewed were designed with the ITC framework in mind. As such, our evaluation of whether a domain was present or not represents our best assessment based on our review of these reports and understanding of the ITC. However, implementation of the intervention is infrequently described, and it is possible that the described and actual interventions varied significantly. No study included all ten domains, making our conclusions about the relative influence of inclusion of one domain versus another limited.

Publication bias may play a role in our findings, though we think the strong negative publication record in this regard limits its influence. Published reports may have other biases (academic settings, urban locations) that affect our findings, though analysis of these biases is beyond the scope of this analysis. Our measures of quality were limited to study size, general design, and duration. Other important methodologic constructs such as appropriateness of sampling, data collection, analysis plan, and generalizability were not captured and infrequently reported. While we note inclusion of these elements did not affect findings in prior systematic reviews [4], it is possible their inclusion could have affected our findings.

We excluded pediatric, obstetric, psychiatric, and surgical populations as their reasons for readmission may differ from medical patients. Domains in the ITC may not be independent of one another, but a formal principle components or factor analysis was beyond the scope of our review. We did not use the techniques of a meta-analysis, as the wide variability of the existing literature prevents this level of analysis. We also did not use the reporting standards of a formal systematic review, though we did search systematically for studies that met criteria for analysis. Our approach was necessarily more narrative and thus should be considered hypothesis-generating and requiring further prospective study.

Conclusions

Improving transitions of care from the hospital to the community requires multifaceted interventions targeting multidimensional risk factors present in patients discharged from the hospital. Until readmission risk factors- individually and collectively- are better understood and assessed, designing interventions to address these multifactorial risk factors using a framework like the ITC may be effective. In addition, incorporating systems actively involving patients in promoting self-management in their care, developing care processes to address active symptom development in the post-discharge period, and providing social and community support for this management merit special inclusion in any intervention. Future work evaluating the role of the Ideal Transition of Care framework in evaluating risk and designing interventions for individual patients may show benefit in providing cost-effective, safe transitional care.

References

Forster AJ, Murff HJ, Peterson JF, Gandhi TK, Bates DW: The incidence and severity of adverse events affecting patients after discharge from the hospital. Ann Intern Med. 2003, 138 (3): 161-167. 10.7326/0003-4819-138-3-200302040-00007.

Jencks SF, Williams MV, Coleman EA: Rehospitalizations among patients in the Medicare fee-for-service program. N Engl J Med. 2009, 360 (14): 1418-1428. 10.1056/NEJMsa0803563.

Burke RE, Coleman EA: Interventions to decrease hospital readmissions: keys for cost-effectiveness. JAMA Intern Med. 2013, 173 (8): 695-698. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.171.

Hansen LO, Young RS, Hinami K, Leung A, Williams MV: Interventions to reduce 30-day rehospitalization: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2011, 155 (8): 520-528. 10.7326/0003-4819-155-8-201110180-00008.

Burke RE, Kripalani S, Vasilevskis EE, Schnipper JL: Moving beyond readmission penalties: creating an ideal process to improve transitional care. J Hosp Med. 2013, 8 (2): 102-109. 10.1002/jhm.1990.

Balaban RB, Weissman JS, Samuel PA, Woolhandler S: Redefining and redesigning hospital discharge to enhance patient care: a randomized controlled study. J Gen Intern Med. 2008, 23 (8): 1228-1233. 10.1007/s11606-008-0618-9.

Braun E, Baidusi A, Alroy G, Azzam ZS: Telephone follow-up improves patients satisfaction following hospital discharge. Eur J Intern Med. 2009, 20 (2): 221-225. 10.1016/j.ejim.2008.07.021.

Coleman EA, Parry C, Chalmers S, Min SJ: The care transitions intervention: results of a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2006, 166: 1822-1828. 10.1001/archinte.166.17.1822.

Dudas V, Bookwalter T, Kerr KM, Pantilat SZ: The impact of follow-up telephone calls to patients after hospitalization. Am J Med. 2001, 111 (9B): 26S-30S.

Dunn RB, Lewis PA, Vetter NJ, Guy PM, Hardman CS, Jones RW: Health visitor intervention to reduce days of unplanned hospital re-admission in patients recently discharged from geriatric wards: the results of a randomised controlled study. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 1994, 18 (1): 15-23. 10.1016/0167-4943(94)90044-2.

Evans RL, Hendricks RD: Evaluating hospital discharge planning: a randomized clinical trial. Med Care. 1993, 31 (4): 358-370. 10.1097/00005650-199304000-00007.

Forster AJ, Clark HD, Menard A, Dupuis N, Chernish R, Chandok N, Khan A, Letourneau M, van Walraven C: Effect of a nurse team coordinator on outcomes for hospitalized medicine patients. Am J Med. 2005, 118 (10): 1148-1153. 10.1016/j.amjmed.2005.04.019.

Jaarsma T, Halfens R, Huijer Abu-Saad H, Dracup K, Gorgels T, van Ree J, Stappers J: Effects of education and support on self-care and resource utilization in patients with heart failure. Eur Heart J. 1999, 20 (9): 673-682. 10.1053/euhj.1998.1341.

Jack BW, Chetty VK, Anthony D, Greenwald JL, Sanchez GM, Johnson AE, Forsythe SR, O'Donnell JK, Paasche-Orlow MK, Manasseh C, Martin S, Culpepper L: A reengineered hospital discharge program to decrease rehospitalization: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2009, 150: 178-187. 10.7326/0003-4819-150-3-200902030-00007.

Koehler BE, Richter KM, Youngblood L, Cohen BA, Prengler ID, Cheng D, Masica AL: Reduction of 30-day postdischarge hospital readmission or emergency department (ED) visit rates in high-risk elderly medical patients through delivery of a targeted care bundle. J Hosp Med. 2009, 4 (4): 211-218. 10.1002/jhm.427.

Kwok T, Lum CM, Chan HS, Ma HM, Lee D, Woo J: A randomized, controlled trial of an intensive community nurse-supported discharge program in preventing hospital readmissions of older patients with chronic lung disease. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004, 52 (8): 1240-1246. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52351.x.

McDonald K, Ledwidge M, Cahill J, Kelly J, Quigley P, Maurer B, Begley F, Ryder M, Travers B, Timmons L, Burke T: Elimination of early rehospitalization in a randomized, controlled trial of multidisciplinary care in a high-risk, elderly heart failure population: the potential contributions of specialist care, clinical stability and optimal angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor dose at discharge. Eur J Heart Fail. 2001, 3 (2): 209-215. 10.1016/S1388-9842(00)00134-3.

Naylor M, Brooten D, Jones R, Lavizzo-Mourey R, Mezey M, Pauly M: Comprehensive discharge planning for the hospitalized elderly. A randomized clinical trial. Ann Intern Med. 1994, 120: 999-1006. 10.7326/0003-4819-120-12-199406150-00005.

Rainville EC: Impact of pharmacist interventions on hospital readmissions for heart failure. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 1999, 56 (13): 1339-1342.

Wong FK, Chow S, Chung L, Chang K, Chan T, Lee WM, Lee R: Can home visits help reduce hospital readmissions? Randomized controlled trial. J Adv Nurs. 2008, 62 (5): 585-595. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2008.04631.x.

Atienza F, Anguita M, Martinez-Alzamora N, Osca J, Ojeda S, Almenar L, Ridocci F, Vallés F, de Velasco JA, PRICE Study Group: Multicenter randomized trial of a comprehensive hospital discharge and outpatient heart failure management program. Eur J Heart Fail. 2004, 6 (5): 643-652. 10.1016/j.ejheart.2003.11.023.

Blue L, Lang E, McMurray JJ, Davie AP, McDonagh TA, Murdoch DR, Petrie MC, Connolly E, Norrie J, Round CE, Ford I, Morrison CE: Randomised controlled trial of specialist nurse intervention in heart failure. BMJ. 2001, 323 (7315): 715-718. 10.1136/bmj.323.7315.715.

Bourbeau J, Julien M, Maltais F, Rouleau M, Beaupré A, Bégin R, Renzi P, Nault D, Borycki E, Schwartzman K, Singh R, Collet JP: Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease axis of the Respiratory Network Fonds de la Recherche en Santé du Québec. Reduction of hospital utilization in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a disease-specific self-management intervention. Arch Intern Med. 2003, 163 (5): 585-591. 10.1001/archinte.163.5.585.

Chaudhry SI, Mattera JA, Curtis JP, Spertus JA, Herrin J, Lin Z, Phillips CO, Hodshon BV, Cooper LS, Krumholz HM: Telemonitoring in patients with heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2010, 363 (24): 2301-2309. 10.1056/NEJMoa1010029.

Cline CM, Israelsson BY, Willenheimer RB, Broms K, Erhardt LR: Cost effective management programme for heart failure reduces hospitalisation. Heart. 1998, 80 (5): 442-446.

DeBusk RF, Miller NH, Parker KM, Bandura A, Kraemer HC, Cher DJ, West JA, Fowler MB, Greenwald G: Care management for low-risk patients with heart failure: a randomized, controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2004, 141 (8): 606-613. 10.7326/0003-4819-141-8-200410190-00008.

Doughty RN, Wright SP, Pearl A, Walsh HJ, Muncaster S, Whalley GA, Gamble G, Sharpe N: Randomized, controlled trial of integrated heart failure management: The Auckland Heart Failure Management Study. Eur Heart J. 2002, 23 (2): 139-146. 10.1053/euhj.2001.2712.

Ekman I, Andersson B, Ehnfors M, Matejka G, Persson B, Fagerberg B: Feasibility of a nurse-monitored, outpatient-care programme for elderly patients with moderate-to-severe, chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J. 1998, 19 (8): 1254-1260. 10.1053/euhj.1998.1095.

Gillespie U, Alassaad A, Henrohn D, Garmo H, Hammarlund-Udenaes M, Toss H, Kettis-Lindblad A, Melhus H, Mörlin C: A comprehensive pharmacist intervention to reduce morbidity in patients 80 years or older: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2009, 169 (9): 894-900. 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.71.

Holland R, Lenaghan E, Harvey I, Smith R, Shepstone L, Lipp A, Christou M, Evans D, Hand C: Does home based medication review keep older people out of hospital? The HOMER randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2005, 330 (7486): 293-10.1136/bmj.38338.674583.AE.

Kasper EK, Gerstenblith G, Hefter G, Van Anden E, Brinker JA, Thiemann DR, Terrin M, Forman S, Gottlieb SH: A randomized trial of the efficacy of multidisciplinary care in heart failure outpatients at high risk of hospital readmission. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002, 39 (3): 471-480. 10.1016/S0735-1097(01)01761-2.

Kimmelstiel C, Levine D, Perry K, Patel AR, Sadaniantz A, Gorham N, Cunnie M, Duggan L, Cotter L, Shea-Albright P, Poppas A, LaBresh K, Forman D, Brill D, Rand W, Gregory D, Udelson JE, Lorell B, Konstam V, Furlong K, Konstam MA: Randomized, controlled evaluation of short- and long-term benefits of heart failure disease management within a diverse provider network: the SPAN-CHF trial. Circulation. 2004, 110 (11): 1450-1455. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000141562.22216.00.

Koelling TM, Johnson ML, Cody RJ, Aaronson KD: Discharge education improves clinical outcomes in patients with chronic heart failure. Circulation. 2005, 111 (2): 179-185. 10.1161/01.CIR.0000151811.53450.B8.

Laramee AS, Levinsky SK, Sargent J, Ross R, Callas P: Case management in a heterogeneous congestive heart failure population: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2003, 163 (7): 809-817. 10.1001/archinte.163.7.809.

Ledwidge M, Barry M, Cahill J, Ryan E, Maurer B, Ryder M, Travers B, Timmons L, McDonald K: Is multidisciplinary care of heart failure cost-beneficial when combined with optimal medical care?. Eur J Heart Fail. 2003, 5 (3): 381-389. 10.1016/S1388-9842(02)00235-0.

Mejhert M, Kahan T, Persson H, Edner M: Limited long term effects of a management programme for heart failure. Heart. 2004, 90 (9): 1010-1015. 10.1136/hrt.2003.014407.

Murray MD, Young J, Hoke S, Tu W, Weiner M, Morrow D, Stroupe KT, Wu J, Clark D, Smith F, Gradus-Pizlo I, Weinberger M, Brater DC: Pharmacist intervention to improve medication adherence in heart failure: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2007, 146 (10): 714-725. 10.7326/0003-4819-146-10-200705150-00005.

Nazareth I, Burton A, Shulman S, Smith P, Haines A, Timberal H: A pharmacy discharge plan for hospitalized elderly patients–a randomized controlled trial. Age Ageing. 2001, 30 (1): 33-40. 10.1093/ageing/30.1.33.

Peikes D, Peterson G, Brown R, Graff S, Lynch J: How Changes In Washington University’s Medicare Coordinated Care Demonstration Pilot Ultimately Achieved Savings. Health Aff. 2012, 31 (6): 1216-1226. 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0593.

Rich MW, Beckham V, Wittenberg C, Leven CL, Freedland KE, Carney RM: A multidisciplinary intervention to prevent the readmission of elderly patients with congestive heart failure. N Engl J Med. 1995, 333 (18): 1190-1195. 10.1056/NEJM199511023331806.

Riegel B, Carlson B, Kopp Z, LePetri B, Glaser D, Unger A: Effect of a standardized nurse case-management telephone intervention on resource use in patients with chronic heart failure. Arch Intern Med. 2002, 162 (6): 705-712. 10.1001/archinte.162.6.705.

Stewart S, Marley JE, Horowitz JD: Effects of a multidisciplinary, home-based intervention on unplanned readmissions and survival among patients with chronic congestive heart failure: a randomised controlled study. Lancet. 1999, 354 (9184): 1077-1083. 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)03428-5.

Strömberg A, Mårtensson J, Fridlund B, Levin LA, Karlsson JE, Dahlström U: Nurse-led heart failure clinics improve survival and self-care behaviour in patients with heart failure: results from a prospective, randomised trial. Eur Heart J. 2003, 24 (11): 1014-1023. 10.1016/S0195-668X(03)00112-X.

Takahashi PY, Pecina JL, Upatising B, Chaudhry R, Shah ND, Van Houten H, Cha S, Croghan I, Naessens JM, Hanson GJ: A randomized controlled trial of telemonitoring in older adults with multiple health issues to prevent hospitalizations and emergency department visits. Arch Intern Med. 2012, 172 (10): 773-779.

Tsuyuki RT, Fradette M, Johnson JA, Bungard TJ, Eurich DT, Ashton T, Gordon W, Ikuta R, Kornder J, Mackay E, Manyari D, O'Reilly K, Semchuk W: A multicenter disease management program for hospitalized patients with heart failure. J Card Fail. 2004, 10 (6): 473-480. 10.1016/j.cardfail.2004.02.005.

Weinberger M, Oddone EZ, Henderson WG: Does increased access to primary care reduce hospital readmissions? Veterans Affairs Cooperative Study Group on Primary Care and Hospital Readmission. N Engl J Med. 1996, 334 (22): 1441-1447. 10.1056/NEJM199605303342206.

Marusic S, Gojo-Tomic N, Erdeljic V, Bacic-Vrca V, Franic M, Kirin M, Bozikov V: The effect of pharmacotherapeutic counseling on readmissions and emergency department visits. Int J Clin Pharm. 2013, 35 (1): 37-44. 10.1007/s11096-012-9700-9.

Anderson C, Deepak BV, Amoateng-Adjepong Y, Zarich S: Benefits of comprehensive inpatient education and discharge planning combined with outpatient support in elderly patients with congestive heart failure. Congest Heart Fail. 2005, 11 (6): 315-321. 10.1111/j.1527-5299.2005.04458.x.

Bostrom J, Caldwell J, McGuire K, Everson D: Telephone follow-up after discharge from the hospital: does it make a difference?. Appl Nurs Res. 1996, 9 (2): 47-52. 10.1016/S0897-1897(96)80402-2.

Gow P, Berg S, Smith D, Ross D: Care co-ordination improves quality-of-care at South Auckland Health. J Qual Clin Pract. 1999, 19 (2): 107-110. 10.1046/j.1440-1762.1999.00312.x.

Harrison PL, Hara PA, Pope JE, Young MC, Rula EY: The impact of postdischarge telephonic follow-up on hospital readmissions. Popul Health Manag. 2011, 14 (1): 27-32. 10.1089/pop.2009.0076.

Einstadter D, Cebul RD, Franta PR: Effect of a nurse case manager on postdischarge follow-up. J Gen Intern Med. 1996, 11 (11): 684-688. 10.1007/BF02600160.

Lucas KS: Outcomes evaluation of a pharmacist discharge medication teaching service. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 1998, 55 (24 Suppl 4): S32-S35.

McPhee SJ, Frank DH, Lewis C, Bush DE, Smith CR: Influence of a “discharge interview” on patient knowledge, compliance, and functional status after hospitalization. Med Care. 1983, 21 (8): 755-767. 10.1097/00005650-198308000-00001.

O’Dell KM, Kucukarslan SN: Impact of the clinical pharmacist on readmission in patients with acute coronary syndrome. Ann Pharmacother. 2005, 39 (9): 1423-1427. 10.1345/aph.1E640.

Sorknaes AD, Madsen H, Hallas J, Jest P, Hansen-Nord M: Nurse tele-consultations with discharged COPD patients reduce early readmissions—an interventional study. Clin Respir J. 2011, 5 (1): 26-34. 10.1111/j.1752-699X.2010.00187.x.

Steeman E, Moons P, Milisen K, De Bal N, De Geest S, De Froidmont C, Tellier V, Gosset C, Abraham I: Implementation of discharge management for geriatric patients at risk of readmission or institutionalization. Int J Qual Health Care. 2006, 18 (5): 352-358. 10.1093/intqhc/mzl026.

Walker PC, Bernstein SJ, Jones JN, Piersma J, Kim HW, Regal RE, Kuhn L, Flanders SA: Impact of a pharmacist-facilitated hospital discharge program: a quasi-experimental study. Arch Intern Med. 2009, 169 (21): 2003-2010. 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.398.

Ohuabunwa U, Jordan Q, Shah S, Fost M, Flacker J: Implementation of a care transitions model for low-income older adults: a high-risk, vulnerable population. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013, 61 (6): 987-992. 10.1111/jgs.12276.

Brown A, Caplan G: A post-acute respiratory outreach service. Aust J Adv Nurs. 1997, 14 (4): 5-11.

Creason H: Congestive heart failure telemanagement clinic. Lippincotts Case Manag. 2001, 6 (4): 146-156. 10.1097/00129234-200107000-00004.

Dai YT, Chang Y, Hsieh CY, Tai TY: Effectiveness of a pilot project of discharge planning in Taiwan. Res Nurs Health. 2003, 26 (1): 53-63. 10.1002/nur.10067.

Dedhia P, Kravet S, Bulger J, Hinson T, Sridharan A, Kolodner K, Wright S, Howell E: A quality improvement intervention to facilitate the transition of older adults from three hospitals back to their homes. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009, 57 (9): 1540-1546. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02430.x.

Hess DR, Tokarczyk A, O’Malley M, Gavaghan S, Sullivan J, Schmidt U: The value of adding a verbal report to written handoffs on early readmission following prolonged respiratory failure. Chest. 2010, 138 (6): 1475-1479. 10.1378/chest.09-2140.

Houghton A, Bowling A, Clarke KD, Hopkins AP, Jones I: Does a dedicated discharge coordinator improve the quality of hospital discharge?. Qual Health Care. 1996, 5 (2): 89-96. 10.1136/qshc.5.2.89.

Kramer JS, Hopkins PJ, Rosendale JC, Garrelts JC, Hale LS, Nester TM, Cochran P, Eidem LA, Haneke RD: Implementation of an electronic system for medication reconciliation. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2007, 64 (4): 404-422. 10.2146/ajhp060506.

Smith CS: The impact of an ambulatory firm system on quality and continuity of care. Med Care. 1995, 33 (3): 221-226. 10.1097/00005650-199503000-00001.

Mudge A, Denaro C, Scott I, Bennett C, Hickey A, Jones MA: The paradox of readmission: effect of a quality improvement program in hospitalized patients with heart failure. J Hosp Med. 2010, 5 (3): 148-153. 10.1002/jhm.563.

Amarasingham R, Patel PC, Toto K, Nelson LL, Swanson TS, Moore BJ, Xie B, Zhang S, Alvarez KS, Ma Y, Drazner MH, Kollipara U, Halm EA: Allocating scarce resources in real-time to reduce heart failure readmissions: a prospective, controlled study. BMJ Qual Saf. 2013, 22 (12): 998-1005. 10.1136/bmjqs-2013-001901.

Garin N, Carballo S, Gerstel E, Lerch R, Meyer P, Zare M, Zawodnik A, Perrier A: Inclusion into a heart failure critical pathway reduces the risk of death or readmission after hospital discharge. Eur J Intern Med. 2012, 23 (8): 760-764. 10.1016/j.ejim.2012.06.006.

Graham J, Tomcavage J, Salek D, Sciandra J, Davis DE, Stewart WF: Postdischarge monitoring using interactive voice response system reduces 30-day readmission rates in a case-managed Medicare population. Med Care. 2012, 50 (1): 50-57. 10.1097/MLR.0b013e318229433e.

Cochrane Effective Practice and Organization of Care Group: EPOC resources for review authors. 2013, Accessed at http://epocoslo.cochrane.org/epoc-specific-resources-review-authors on 15 May 2013

Kansagara D, Englander H, Salanitro A, Kagen D, Theobald C, Freeman M, Kripalani S: Risk prediction models for hospital readmission: a systematic review. JAMA. 2011, 306 (15): 1688-1698. 10.1001/jama.2011.1515.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6963/14/423/prepub

Acknowledgements

Dr. Burke was supported by the VA’s Colorado Research to Improve Care Coordination Research Enhancement Award Program.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

BB – conception, design, acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data, manuscript drafting and revision, RG – analysis, interpretation of data, drafting and revising of manuscript, AP – analysis and interpretation of data, revising of manuscript, GM – conception, design, acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data, manuscript revision. All authors have read and approved the final version, and are accountable for all aspects of accuracy and integrity of the work.

Electronic supplementary material

12913_2014_3510_MOESM1_ESM.docx

Additional file 1: The Ideal Transition of Care Framework. Description of data: The Ideal Transition of Care Framework is graphically displayed. (DOCX 112 KB)

12913_2014_3510_MOESM2_ESM.pdf

Additional file 2: Categorization of ITC domains by included intervention. Description of data: Interventions included are listed with each of the ten domains of the ITC judged present (1) or absent (0) by reviewers. (PDF 238 KB)

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Burke, R.E., Guo, R., Prochazka, A.V. et al. Identifying keys to success in reducing readmissions using the ideal transitions in care framework. BMC Health Serv Res 14, 423 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-14-423

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-14-423