Abstract

Background

While prophylactic human papilloma virus (HPV) vaccination is considered effective in young girls, it is unclear whether a catch-up vaccination of older girls would be beneficial. We, therefore, aimed to examine the potential health impact of a HPV catch-up vaccination of girls who were too old at the time of vaccine introduction, hence aged 16 and older.

Methods

We systematically searched the literature for randomized clinical trials (RCTs) that examined the effect of HPV vaccines on overall mortality, cancer mortality and incidence, high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 and higher (CIN2+), vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN) and vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia (VaIN) grade 2 and higher lesions (VIN2+ and VaIN2+, respectively) genital warts (condyloma). We considered all lesions and those associated with HPV type(s) included in the vaccines. RCTs reporting on serious adverse events were also eligible. Selected publications were assessed for potential risk of bias, and we ascertained the overall quality of the evidence for each outcome using Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE). Meta-analyses were performed, assuming both random and fixed effects, to estimate risk ratios (RR) and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI), using intention-to-treat and per-protocol populations.

Results

We included 46 publications reporting on 13 RCTs. Most of the RCTs had a maximum follow-up period of four years. We identified no RCT reporting on the effect of HPV catch vaccination on overall and cancer related mortality, and on cervical cancer incidence. We found a borderline protective effect of a HPV catch-up vaccination on all CIN2+, with a pooled RR of 0.80 (95% CI: 0.62-1.02) for a follow-up period of 4 years. A HPV catch-up vaccination was associated with a reduction in VIN2+ and VaIN2+ lesions, and condyloma. No difference in risk of serious adverse events was seen in vaccinated participants versus unvaccinated women (pooled RR of 0.99 (0.91-1.08)).

Conclusions

This systematic review indicates that a HPV catch-up vaccination could be beneficial, however the long-term effect of such a vaccination, and its effect on cervical cancer incidence and mortality is still unclear.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Human papillomavirus (HPV) is considered the most common sexually transmitted agent worldwide [1], and most sexually active women and men will experience an HPV infection during their lifetime [2]. More than 100 types of HPV have been identified [3, 4]. However, a small number of HPV types contribute to a large proportion of HPV-related diseases. Most HPV infections resolve within 1-2 years [4], but some are persistent and are recognised as a necessary cause of cervical cancer and for its precursor lesions [4, 5]. Approximately 70% of cervical cancers in the world are attributed to two of the most common HPV types, 16 and 18 [4, 6, 7]. The World Health Organisation (WHO) International Agency for Research on Cancer judged that there was sufficient evidence to support a causal role of HPV 16 infection in carcinoma of the cervix, vulva, vagina, penis, anus, oral cavity, and oropharynx and tonsil [8]. The evidence was also judged sufficient to recognize a causal role of HPV types 18, 31, 33, 35, 39, 45, 51, 52, 56, 58, and 59 in cervical cancer [8]. It was estimated that 5.2% of all cancers worldwide are attributed to HPV infections [7]. Genital warts have been linked to HPV infection [9], with approximately 100% of genital warts (condyloma acuminate) caused by either HPV 6 or 11 [10]. An increasing incidence of genital warts has been described over recent decades in Europe [11].

Efficient prophylactic vaccines could have an important public health impact [12]. Since 2006, two vaccines (Cervarix and Gardasil) have been licensed for girls aged 9 to 26, and through age 45 years in some countries [13], and have been introduced in the childhood immunisation programme in many countries for girls aged 9 to 18 [14]. While prophylactic HPV vaccination has been shown to be effective in young girls, it is still unclear whether a catch-up vaccination of girls who were too old at time of vaccine introduction would be beneficial.

To the best of our knowledge, three meta-analyses have been published to date and they reported results on the effect of HPV vaccination of older girls on persistent HPV infection [15], and only on outcomes associated with the HPV types included in HPV vaccines [16, 17]. In this systematic review, we present results on prevention of all lesions regardless of the HPV status of the lesions. This is an appropriate measure of the public health impact of a HPV catch-up vaccination, as it estimates more accurately the expected reduction in total disease burden after implementation of such a vaccination program.

In this article, we present a systematic review of the international literature to investigate the health impact of a HPV catch-up vaccination of girls who were too old at the time of vaccine introduction. Taking into account the age range covered by HPV vaccines licensing, and the age at introduction of HPV vaccination in different countries, we have therefore examined the health impact of HPV vaccination of girls aged 16 and older.

Methods

Eligibility criteria

We included randomised clinical trials (RCT) that examined the efficacy of a HPV catch-up vaccination of young women aged 16 and older. Eligible RCTs examined the effect of HPV vaccines on overall mortality, cancer related mortality, cervical cancer, high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grades 2 and higher (CIN2+), vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN) and vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia (VaIN) grade 2 and higher lesions (VIN2+ and VaIN2+, respectively), and genital warts (condyloma). RCTs investigating HPV vaccination safety and reporting on serious adverse events were also eligible. RCTs that used the following comparison groups were included: HPV vaccine against placebo, HPV vaccine against placebo with in addition another vaccine (such as hepatitis B vaccine) used in the intervention and in the placebo groups, or RCTs comparing two different HPV vaccines. No language restriction was applied during the literature search.

The literature search

We systematically searched several databases from 1999 up to October 2012 (Ovid MEDLINE(R) In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations, Ovid MEDLINE(R), Embase, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, ISI web of Science, PubMed, and Google scholar). Details of the search strategy are provided in the Additional file 1: Appendix. Furthermore, we contacted the pharmaceutical companies with marketing authorization for HPV vaccines in Norway (GlaxoSmithKline AS and Sanofi Pasteur MSD) to obtain additional relevant information. The search was supplemented with papers found in bibliographies of selected articles. We used a search filter to select only RCTs.

Examined outcomes

To assess the potential health impact of a HPV catch-up vaccination, we have examined several outcomes. We planned to investigate the effect of a HPV catch-up vaccination on overall and cancer mortality, and on cervical cancer incidence. Furthermore, we aimed to examine several female genital HPV related diseases and investigate the association between HPV vaccination and these outcomes. These outcomes were CIN2+, VIN2+, VaIN2+ and genital warts (condyloma acuminata). We also examined the association between HPV vaccination and these lesions considering only HPV related lesions (i.e. HPV type(s) found in the lesion is/are the HPV type(s) covered by the examined vaccine).

We examined also adverse events possibly linked to HPV vaccination. We considered only adverse events reported as serious adverse events in the included publications.

Data extraction and quality assessment

The selection of articles was carried out by two of the review authors (divided among EC, LJ and IS). All titles and abstracts from the reference lists of articles were screened, and full-text articles were retrieved for publications judged potentially relevant. Each full-length article was assessed for possible inclusion according to the predefined eligibility criteria. Potential disagreements were resolved by discussion with a review author.

Selected publications were assessed for potential risk of bias according to the Cochrane risk of bias tool [18]. All assessments were performed and agreed upon by two of the review authors. No studies were excluded on the basis of high risk of bias.

One review author extracted the data and another verified the information. When data were reported in several publications, we used the publication with the longest follow-up period. If a publication included several trials, preference was given to the publication that included the most trials. We extracted detailed data on characteristics of the clinical trial and participants, on administration of vaccine and control, and on relevant outcomes.

Two review authors assessed the overall quality of the evidence for each selected outcome using GRADE (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation) [19].

Statistical analyses

When possible, we carried out meta-analyses to investigate the association between HPV vaccination and outcomes described above, comparing vaccine and control groups. Extracted data were pooled together by performing meta-analyses using the Review Manager software (RevMan). When the outcome data could not be pooled in meta-analyses, we described the results in a narrative manner.

Random and fixed effect models were used to calculate pooled risk ratios (RR) and corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI). If we identified fewer than three studies reporting data on the same clinical outcome, we report pooled estimates using fixed effect models. Otherwise, pooled estimates obtained with random effect models are presented.

We performed intention-to-treat (ITT) analyses. However, none of the included studies used an intention-to-treat population including only randomized subjects. We, therefore, used the modified intention-to-treat populations as defined in the included publications. The modified ITT population was most commonly defined as participants who received at least one vaccine or control dose and had at least one follow-up visit post-dose 1. When possible, we conducted also analyses according to per-protocol-population (PPP). The PPP typically included participants who received the three vaccine or control doses. We pooled results published for the safety population, using estimates reported for the longest follow-up period in each study. In most trials, the safety population was similar to the modified ITT population.

Results

Literature search and characteristics of included studies

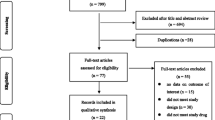

The study selection process is presented in Figure 1. The literature search retrieved 616 references. In addition, we received 12 references from the pharmaceutical companies with marketing authorization for HPV vaccines in Norway. 46 publications, reporting on 13 different RCTs, were selected.

Characteristics from included studies [20–40] are presented in Table 1. Totally, the studies included nearly 40 000 participants. They were conducted in North America (USA and Canada), South America, Europe and Asia. Most clinical trials had a maximum follow-up period of 4 years, with two reporting results after a follow-up of 6 [36], and 8 years [22]. The participants were healthy and non-pregnant women aged 15 to 45 years of age. One of the studies included women aged 9 to 23 years, but the mean age was 17 years [41]. The FUTURE (protocol 19) trial included women aged 24 to 45 (mean age 34 years) [29, 30]. However, we included this study since one of our inclusion criterion was women aged 16 and older. Some studies included only participants with no history of HPV infection and negative HPV tests at entry into the study [34], but most studies recruited participants with fewer than four to six lifetime sex partners [21, 34, 41, 42].

Vaccines used in the trials were the bivalent vaccine containing HPV 16 and 18 virus-like particles (VLP) from GlaxoSmithKline, or the monovalent vaccine containing HPV 16 VLP and the quadrivalent vaccine containing HPV 6, 11, 16 and 18, both from Sanofi Pasteur MSD. All trials used placebo as comparator except for two studies: one used hepatitis B vaccine in both the intervention and the control groups [43], and one compared the bivalent and the quadrivalent vaccines [44]. All vaccines were given as three doses during a six months period (at day 1, months 2 and 6; or at months 0, 1 and 6).

Some of the included studies had unclear allocation concealment and unclear blinding. However, all studies were assessed as having low risk of bias.

While, one of our aims was to investigate the effect of a HPV catch-up vaccination on overall and cancer related mortality, and on the incidence of cervical cancer, no RCT examining these outcomes were identified.

Effect of HPV vaccines on outcomes identified in relevant studies

Table 2 summarises the effects of HPV vaccine versus placebo or no vaccine and the quality of evidence for each outcome.

Overall mortality

Overall mortality was seldom reported, and primarily only in the text. Overall mortality was reported in 7 RCTs [28, 29, 32, 34, 41, 45]. The authors reported that none of the recorded deaths were considered to be related to the intervention in the vaccine or control groups.

CIN2+

The intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis based on five studies showed a borderline statistically significant reduction in CIN2+ lesions associated with HPV vaccination with a pooled RR of 0.80 (95% CI: 0.62-1.02) for a follow-up period of 4 years (Figure 2). The quality of the evidence was judged moderate. Two of the included studies published results for longer follow-up periods, and reported RRs of 0.29 (0.11-0.78) [36], and 0.64 (0.27-1.52) [22] for follow-up of 6 and 8 years, respectively (results not shown).The reported RR using the per protocol population (PPP) showed a non statistically significant reduction for all CIN2+ lesions after a four year follow-up period (RR: 0.49; 95% CI: 0.21-1.14) (Figure 2). However, this finding was based on only one RCT, and the quality of the evidence was considered low.When considering only CIN2+ HPV related lesions, we found statistically significant reductions in risk with HPV vaccination both for studies using ITT and PPP populations (Figure 3). The pooled RRs were 0.54 (0.44-0.67) for the ITT population, and 0.05 (0.01-0.16) for the PPP population, both for a 4 years follow-up period. The quality of the evidence was considered high for both estimates. Two studies reported data for 721 participants from the ITT population for 8 years follow up (Figure 3). The pooled RR was 0.29 (0.09-0.96). The quality of the evidence for this outcome was considered moderate.

VIN2+, VaIN2+

We found a statistically significant reduction in risk of all VIN2+ or VaIN2+ lesions with HPV vaccination (RR = 0.49; 95% CI = 0.32-0.76) based on two RCTs reported in one publication (Figure 4). The quality of the evidence for this outcome was considered moderate. However, when considering only published estimates on HPV related VIN2+ or VaIN2+ (from four studies), the reduction in risk was not statistically significant (pooled RR = 0.72; 0.03-15.02) (Figure 4). The quality of the evidence for this outcome was low.

Condyloma acuminata

HPV vaccination was associated with a reduction in risk of condyloma, both for all condyloma and for those related to HPV types included in HPV vaccines in the ITT population (Figure 5). The reported RR, based on two RCTs, was 0.38 (0.31- 0.47) for all condyloma, and the pooled RR was 0.28 (0.12-0.65) for HPV related condyloma. The quality of the evidence for these two outcomes was high.

Serious adverse events

We included 14 studies that reported estimates of the association between HPV vaccination and serious adverse events. The risk of having a serious adverse event was similar in both the vaccine and control groups (Figure 6). The pooled RR was 0.99 (0.91-1.08). The quality of the evidence for this outcome was moderate.

We identified one publication that compared the bivalent vaccine with the quadrivalent vaccine, and examined possible differences safety between these two vaccines [44]. However, the quality of the evidence was judged low, and no statistically significant difference was found (RR = 1.05; 95% CI: 0.59-1.05) (results not shown).

Discussion

This systematic review shows that there is a protective effect of HPV vaccination against CIN2+ lesions associated with the HPV types included in HPV vaccines, all VIN2+ and VaIN2+, and condyloma acuminate (HPV related and not). The results also indicate a protective effect against all CIN2 lesions (HPV associated and not). No difference in the occurrence of serious adverse events was found in vaccinated participants compared to control groups.

High grade cervical lesions (CIN2+) were proposed by the WHO as an appropriate surrogate outcome for RCTs examining the effect of HPV vaccination [46]. A reason for this was that since screening for cervical cancer is available, conducting RCTs considering cervical cancer as main outcome would be unethical. CIN lesions are precursors of invasive cervical cancer and while most lower grade CIN (i.e. CIN1) regress spontaneously to normal, a higher percentage of CIN2+ become malignant making these lesions a more appropriate outcome to examine [47]. However, when investigating HPV vaccination efficacy, the main outcome of interest remains cervical cancer, and CIN2+ lesions are mainly examined to extrapolate on the possible effect of HPV vaccination on cervical cancer. One should be cautious when interpreting results on CIN2+ lesions on the possible effect of HPV vaccination on cervical cancer risk. For example, differing results for cervical cancer than those published up to date on precursor lesions could be expected if the HPV types involved in precursor lesions were different to those related to cervical cancer. A meta-analysis reported that while HPV 16 and 18 are the two most common types both in high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (HSIL) and squamous cell carcinoma of the cervix (SCC), these HPV types were reported to be more common in SCC than in HSIL with prevalence ratios of 1.21 (95% CI: 1.16-1.26), and 1.79 (1.56-2.10) for HPV 16 and 18, respectively [48]. It is, therefore, possible that higher protective effect of HPV vaccination would be found for HPV related cervical cancers compared to precursor lesions.

HPV vaccines were shown to be highly efficacious to prevent persistent infections with HPV [16, 17, 49, 50]. Previous meta-analyses have presented results only for persistent HPV infection, and pre-cancerous lesions or condyloma associated with HPV types covered by the vaccines [16, 17]. To the best of our knowledge, our systematic review is the first to present the effect of HPV catch-up vaccination on all pre-cancerous lesions and condyloma, considering both all lesions and those associated with particular HPV types. Examining the effect of HPV vaccination on relevant outcomes regardless of these being related to any HPV type enables a more accurate estimate of the total disease reduction that could be expected after vaccination. We found a borderline statistical significant protection of a HPV catch-up vaccination on all CIN2+ lesions. While 4 out of 5 included RCTs found a protective effect of HPV vaccination on all CIN2+ lesions, one trial reported a non statistically significant increased risk associated with HPV vaccination (RR: 1.21, 95% CI: 0.84-1.75). Participants of this study were older than those from other studies (age range: 24 to 45, mean age 34 years), and somewhat older than women who would most commonly be targeted by a catch-up vaccination. Observational studies examining early vaccine impact have shown a decline in high-grade cervical lesions [51].

While HPV types 16 and 18 are the two most common HPV types worldwide, prevalence of HPV types differs geographically [1]. In included trials, participants are from different geographical regions. They are for example, from Northern America where HPV 16 and 53 are the two most common HPV types, or from Southern America were HPV16 and 58 are the most prevalent types [1]. When ascertaining HPV vaccination efficacy using CIN2+ regardless of the lesions being related to HPV types, differing results may be found according to how common the HPV types included in the vaccine(s) are in the geographical area of interest. In regions were the most common HPV types are included in the vaccine, like in Northern Europe where HPV 16 and 18 are the two most common types, one could expect a stronger protective effect of HPV vaccination on all CIN2+ lesions than in areas where other HPV types are more frequent.

While prophylactic HPV vaccination is considered effective and cost-effective in young girls, it is unclear whether a catch-up vaccination of older girls would have beneficial effect on health outcomes. This is primarily due to differences of HPV status between young and older girls, with younger more likely to be free of HPV infection. In the population included in this systematic review, the HPV status of participants varies, because of the age-range examined in this review, and differences in studies inclusion criteria: Some studies included only participants with no history of HPV infection and negative HPV tests at entry into the study [34], and other studies recruited participants with fewer than four to six lifetime sex partners [21, 34, 41, 42]. The population considered in this systematic review is, therefore, representative of a population targeted by a HPV catch-up vaccination that would be composed of girls both HPV naïve and not. Possible differences in HPV vaccination of young women compared to older women could, also, be explained by potential differences in HV distribution by age [52]. Brotherton et al. reported that HPV type 16 was more prevalent among younger women [52].

The conducted RCTs on the efficacy of HPV vaccination have a relatively short follow-up period with most results published up to date based on follow-up periods of approximately four years. Two included trials published results after longer follow-up periods (6 and 8 years) but the results were based on few participants and are inconclusive [22, 36]. The evidence published so far does not allow us to conclude on the long term effect of HPV vaccination. Furthermore, as cancer takes a long time to develop, longer follow-up periods are required to ascertain the efficacy of HPV vaccination in preventing cervical cancer. The use of population-based registries was described as the best study design to answer this question, and preliminary observations suggested that results on vaccine efficacy against cervical cancer could be available within the next 5 to 10 years [53]. Furthermore, due to lack of long follow-up periods of RCTs published to date, the durability of immune response to HPV vaccines is unknown. Further investigation is, therefore, needed to examine whether booster vaccination(s) would be required after initial vaccination.

In most developed countries, national cervical cancer screening programs have been implemented, with a reported reduction in cervical cancer incidence probably partly due to these programs [54–56]. A public health policy aiming at implementing a HPV vaccination should be done considering the interconnection between the HPV vaccination program and the cervical cancer screening program. While HPV vaccination could present a valuable primary prevention for cervical cancer and other HPV related diseases, certain gaps need to be addressed. Although cross-protection against other HPV types than those covered by the vaccines is possible [57], the two vaccines used nowadays do not protect against all HPV types. HPV type replacement following HPV vaccination has also been a discussed issue [58, 59]. However, up to date, it is not clear, whether there will be an increase of HPV types that have also been linked to cancer but not present in HPV vaccines [60]. Lower coverage could be possible for a catch-up vaccination strategy compared to vaccination of the primary target population of young girls recruited, for example, through schools (i.e. 9-13 years old). Finally, while long term efficacy of HPV vaccines is unproven to date, such an efficacy is required to prevent cervical cancer. A good secondary prevention, such as cervical cancer screening programs, could cover these potential gaps in HPV vaccination. However, concerns have been raised on the possible future consequences of HPV vaccination on the attendance at the cervical cancer screening programs, with possible lower compliance among vaccinated women who perceived themselves at lower risk of cervical cancer [61, 62]. Furthermore, since this systematic review indicates a protective effect of HPV vaccination on all CIN2+ lesions, we could therefore foresee a decrease in screening referrals and subsequent treatments of pre-malignant lesions in the future. The current evidence points towards the need of coordinated policies for HPV vaccination and cervical cancer screening [63, 64].

The evidence, to date, shows that a HPV catch-up vaccination can be considered safe, with no differences seen in serious complications between the vaccination and the control groups. However, the number of cases of published clinical studies may not be sufficient to determine the occurrence of rarely occurring (severe) adverse events in a reliable way. Furthermore, due to the relatively short follow-up period since HPV vaccination implementation in different countries, the long-term safety of the vaccines is unclear and needs to be further monitored in future studies. While different adverse events have been reported, as we examined only events reported as serious this ensures a better homogeneity of the ascertained outcome across studies.

Conclusions

This systematic review indicates that HVP catch-up vaccination could be a valuable primary prevention against cervical cancer and national catch up vaccination programs have already been implemented in several countries. However, the long term effect of such a vaccination strategy and its impact on cervical cancer prevention remains to be determined.

Author’s contributions

Conception of design: EC, IS; LKJ, MK. Acquisition of data: EC, IS, LKJ. Analysis and interpretation of data: EC, IS, LKJ, MK. Draft or revising manuscript: EC, IS, LKJ, MK. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Abbreviations

- HPV:

-

Human papilloma virus

- RCT:

-

Randomized clinical trial

- CIN:

-

Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia

- CIN2+:

-

Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 and higher

- VIN:

-

Vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia

- VIN2+:

-

Vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 and higher

- VaiN:

-

Vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia

- VaIN2+:

-

Vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 and higher

- GRADE:

-

Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation

- RR:

-

Risk ratio

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- ITT:

-

Intention-to-treat

- PPP:

-

Per-protocol-population

- WHO:

-

World Health Organisation.

References

de Sanjose S, Diaz M, Castellsague X, Clifford G, Bruni L, Munoz N, Bosch FX: Worldwide prevalence and genotype distribution of cervical human papillomavirus DNA in women with normal cytology: a meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2007, 7 (7): 453-459. 10.1016/S1473-3099(07)70158-5.

Winer RL, Lee SK, Hughes JP, Adam DE, Kiviat NB, Koutsky LA: Genital human papillomavirus infection: incidence and risk factors in a cohort of female university students. Am J Epidemiol. 2003, 157 (3): 218-226. 10.1093/aje/kwf180.

IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans: Human papillomaviruses. IARC monographs on the evaluation of carcinogenic risks to humans / World Health Organization. Int Agency Res Cancer. 2007, 90: 1-636.

Bouvard V, Baan R, Straif K, Grosse Y, Secretan B, Ghissassi FE, Benbrahim-Tallaa L, Guha N, Freeman C, Galichet L, Cogliano V, on behalf of the WHO International Agency for Research on Cancer Monograph Working Group: Biological agents. volume 100 B. a review of human carcinogens. IARC Monogr Eval Carcinog Risks Hum. 2012, 100 (Pt B): 1-441.

Walboomers JM, Jacobs MV, Manos MM, Bosch FX, Kummer JA, Shah KV, Snijders PJ, Peto J, Meijer CJ, Munoz N: Human papillomavirus is a necessary cause of invasive cervical cancer worldwide. J Pathol. 1999, 189 (1): 12-19. 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9896(199909)189:1<12::AID-PATH431>3.0.CO;2-F.

Castellsagué X, de Sanjosé S, Aguado T, Louie KS, Bruni L, Muñoz J, Diaz M, Irwin K, Gacic M, Beauvais O, Albero G, Ferrer E, Byrne S, Bosch FX: HPV and cervical cancer in the 2007 report. Vaccine. 2007, 25 (Suppl 3): C1-C230.

Parkin DM: The global health burden of infection-associated cancers in the year 2002. Int J Cancer. 2006, 118 (12): 3030-3044. 10.1002/ijc.21731.

Bouvard V, Baan R, Straif K, Grosse Y, Secretan B, El GF, Benbrahim-Tallaa L, Guha N, Freeman C, Galichet L, Cogliano V, WHO International Agency for Research on Cancer Monograph Working Group: A review of human carcinogens--Part B: biological agents. Lancet Oncol. 2009, 10 (4): 321-322. 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70096-8.

Brotherton JM, Heywood A, Heley S: The incidence of genital warts in Australian women prior to the national vaccination program. Sex Health. 2009, 6 (3): 178-184. 10.1071/SH08079. doi: 110.1071/SH08079

Lacey CJ, Lowndes CM, Shah KV: Chapter 4: burden and management of non-cancerous HPV-related conditions: HPV-6/11 disease. Vaccine. 2006, 24 (Suppl 3): S3/35-S33/41.

Hartwig S, Syrjanen S, Dominiak-Felden G, Brotons M, Castellsague X: Estimation of the epidemiological burden of human papillomavirus-related cancers and non-malignant diseases in men in Europe: a review. BMC Cancer. 2012, 12: 30-10.1186/1471-2407-12-30.

Brotherton JM: How much cervical cancer in Australia is vaccine preventable? a meta-analysis. Vaccine. 2008, 26 (2): 250-256. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.10.057. Epub 2007 Nov 2020

Plotkin S, Orenstein O, Offit P: Vaccines. 2013, Elsevier, ISBN: 978-1-4557-0090-5

Markowitz LE, Tsu V, Deeks SL, Cubie H, Wang SA, Vicari AS, Brotherton JM: Human papillomavirus vaccine introduction--the first five years. Vaccine. 2012, 30 (Suppl 5): F139-F148. doi:110.1016/j.vaccine.2012.1005.1039

La Torre G, de Waure C, Chiaradia G, Mannocci A, Ricciardi W: HPV vaccine efficacy in preventing persistent cervical HPV infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Vaccine. 2007, 25 (50): 8352-8358. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.09.027. Epub 2007 Sep 8329

Rambout L, Hopkins L, Hutton B, Fergusson D: Prophylactic vaccination against human papillomavirus infection and disease in women: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. CMAJ. 2007, 177 (5): 469-479. 10.1503/cmaj.070948.

Lu B, Kumar A, Castellsague X, Giuliano AR: Efficacy and safety of prophylactic vaccines against cervical HPV infection and diseases among women: a systematic review & meta-analysis. BMC Infect Dis. 2011, 11: 13-10.1186/1471-2334-11-13. 2011. Article Number

Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 [updated March 2011]. Edited by: Higgins JPT, Green S. 2011, The Cochrane Collaboration, Available from http://handbook.cochrane.org/

Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Vist GE, Kunz R, Falck-Ytter Y, Alonso-Coello P, Schunemann HJ: GRADE: an emerging consensus on rating quality of evidence and strength of recommendations. BMJ. 2008, 336 (7650): 924-926. 10.1136/bmj.39489.470347.AD. doi:910.1136/bmj.39489.470347.AD

Mao C, Koutsky LA, Ault KA, Wheeler CM, Brown DR, Wiley DJ, Alvarez FB, Bautista OM, Jansen KU, Barr E: Efficacy of human papillomavirus-16 vaccine to prevent cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2006, 107 (1): 18-27. 10.1097/01.AOG.0000192397.41191.fb.

Koutsky LA, Ault KA, Wheeler CM, Brown DR, Barr E, Alvarez FB, Chiacchierini LM, Jansen KU: A controlled trial of a human papillomavirus type 16 vaccine. New Engl J Med. 2002, 347 (21): 1645-1651. 10.1056/NEJMoa020586.

Rowhani-Rahbar A, Mao C, Hughes JP, Alvarez FB, Bryan JT, Hawes SE, Weiss NS, Koutsky LA: Longer term efficacy of a prophylactic monovalent human papillomavirus type 16 vaccine. Vaccine. 2009, 27 (41): 5612-5619. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.07.027.

Ault KA: Effect of prophylactic human papillomavirus L1 virus-like-particle vaccine on risk of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2, grade 3, and adenocarcinoma in situ: a combined analysis of four randomised clinical trials. Lancet. 2007, 369 (9576): 1861-1868. 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60852-6.

Villa LL, Costa RLR, Petta CA, Andrade RP, Paavonen J, Iversen O-E, Olsson S-E, Hoye J, Steinwall M, Riis-Johannessen G, Andersson-Ellstrom A, Elfgren K, Krogh G, Lehtinen M, Malm C, Tamms GM, Giacoletti K, Lupinacci L, Railkar R, Taddeo FJ, Bryan J, Esser MT, Sings HL, Saah AJ, Barr E: High sustained efficacy of a prophylactic quadrivalent human papillomavirus types 6/11/16/18 L1 virus-like particle vaccine through 5 years of follow-up. Br J Cancer. 2006, 95 (11): 1459-1466. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603469.

Munoz N, Kjaer SK, Sigurdsson K, Iversen O-E, Hernandez-Avila M, Wheeler CM, Perez G, Brown DR, Koutsky LA, Tay EH, Garcia PJ, Ault KA, Garland SM, Leodolter S, Olsson SE, Tang GW, Ferris DG, Paavonen J, Steben M, Bosch FX, Dillner J, Huh WK, Joura EA, Kurman RJ, Majewski S, Myers ER, Villa LL, Taddeo FJ, Roberts C, Tadesse A, et al: Impact of Human Papillomavirus (HPV)-6/11/16/18 Vaccine on All HPV-Associated Genital Diseases in Young Women. J Nat Cancer Inst. 2010, 102 (5): 325-339. 10.1093/jnci/djp534.

Kjaer SK, Sigurdsson K, Iversen O-E, Hernandez-Avila M, Wheeler CM, Perez G, Brown DR, Koutsky LA, Eng HT, Garcia P, Ault KA, Garland SM, Leodolter S, Olsson SE, Tang GW, Ferris DG, Paavonen J, Lehtinen M, Steben M, Bosch FX, Dillner J, Joura EA, Majewski S, Muñoz N, Myers ER, Villa LL, Taddeo FJ, Roberts C, Tadesse A, Bryan J, et al: A pooled analysis of continued prophylactic efficacy of quadrivalent human papillomavirus (types 6/11/16/18) vaccine against high-grade cervical and external genital lesions. Cancer Prev Res. 2009, 2 (10): 868-878. 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-09-0031.

Dillner J, Kjaer SK, Wheeler CM, Sigurdsson K, Iversen O-E, Hernandez-Avila M, Perez G, Brown DR, Koutsky LA, Tay EH, García P, Ault KA, Garland SM, Leodolter S, Olsson SE, Tang GW, Ferris DG, Paavonen J, Lehtinen M, Steben M, Bosch FX, Joura EA, Majewski S, Muñoz N, Myers ER, Villa LL, Taddeo FJ, Roberts C, Tadesse A, Bryan JT: Four year efficacy of prophylactic human papillomavirus quadrivalent vaccine against low grade cervical, vulvar, and vaginal intraepithelial neoplasia and anogenital warts: Randomised controlled trial. BMJ (Online). 2010, 341 (7766): 239-

Garland SM, Hernandez-Avila M, Wheeler CM, Perez G, Harper DM, Leodolter S, Tang GWK, Ferris DG, Steben M, Bryan J, Taddeo FJ, Railkar R, Esser MT, Sings HL, Nelson M, Boslego J, Sattler C, Barr E, Koutsky LA, Females United to Unilaterally Reduce Endo/Ectocervical Disease (FUTURE) I Investigators: Quadrivalent vaccine against human papillomavirus to prevent anogenital diseases. New Engl J Med. 2007, 356 (19): 1928-1943. 10.1056/NEJMoa061760.

Castellsague X, Muñoz N, Pitisuttithum P, Ferris D, Monsonego J, Ault K, Luna J, Myers E, Mallary S, Bautista OM, Bryan J, Vuocolo S, Haupt RM, Saah A: End-of-study safety, immunogenicity, and efficacy of quadrivalent HPV (types 6, 11, 16, 18) recombinant vaccine in adult women 24-45 years of age. Br J Cancer. 2011, 105 (1): 28-37. 10.1038/bjc.2011.185.

Muñoz N, Manalastas R, Pitisuttithum P, Tresukosol D, Monsonego J, Ault K, Clavel C, Luna J, Myers E, Hood S, Bautista O, Bryan J, Taddeo FJ, Esser MT, Vuocolo S, Haupt RM, Barr E, Saah A: Safety, immunogenicity, and efficacy of quadrivalent human papillomavirus (types 6, 11, 16, 18) recombinant vaccine in women aged 24-45 years: a randomised, double-blind trial. Lancet. 2009, 373 (9679): 1949-1957. 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60691-7.

Paavonen J, Jenkins D, Bosch FX, Naud P, Salmeron J, Wheeler CM, Chow S-N, Apter DL, Kitchener HC, Castellsague X, de Carvalho NS, Skinner SR, Harper DM, Hedrick JA, Jaisamrarn U, Limson GA, Dionne M, Quint W, Spiessens B, Peeters P, Struyf F, Wieting SL, Lehtinen MO, Dubin G, HPV PATRICIA study group: Efficacy of a prophylactic adjuvanted bivalent L1 virus-like-particle vaccine against infection with human papillomavirus types 16 and 18 in young women: an interim analysis of a phase III double-blind, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2007, 369 (9580): 2161-2170. 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60946-5.

Lehtinen M, Paavonen J, Wheeler CM, Jaisamrarn U, Garland SM, Castellsagué X, Skinner SR, Apter D, Naud P, Salmerón J, Chow SN, Kitchener H, Teixeira JC, Hedrick J, Limson G, Szarewski A, Romanowski B, Aoki FY, Schwarz TF, Poppe WA, De Carvalho NS, Germar MJ, Peters K, Mindel A, De Sutter P, Bosch FX, David MP, Descamps D, Struyf F, Dubin G, HPV PATRICIA Study Group: Overall efficacy of HPV-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted vaccine against grade 3 or greater cervical intraepithelial neoplasia: 4-year end-of-study analysis of the randomised, double-blind PATRICIA trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012, 13 (1): 89-99. 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70286-8.

Wheeler CM, Castellsague X, Garland SM, Szarewski A, Paavonen J, Naud P, Salmeron J, Chow S-N, Apter D, Kitchener H, Teixeira JC, Skinner SR, Jaisamrarn U, Limson G, Romanowski B, Aoki FY, Schwarz TF, Poppe WA, Bosch FX, Harper DM, Huh W, Hardt K, Zahaf T, Descamps D, Struyf F, Dubin G, Lehtinen M, HPV PATRICIA Study Group: Cross-protective efficacy of HPV-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted vaccine against cervical infection and precancer caused by non-vaccine oncogenic HPV types: 4-year end-of-study analysis of the randomised, double-blind PATRICIA trial. Lancet Oncol. 2012, 13 (1): 100-110. 10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70287-X.

Harper DM, Franco EL, Wheeler C, Ferris DG, Jenkins D, Schuind A, Zahaf T, Innis B, Naud P, De Carvalho NS, Roteli-Martins CM, Teixeira J, Blatter MM, Korn AP, Quint W, Dubin G, GlaxoSmithKline HPV Vaccine Study Group: Efficacy of a bivalent L1 virus-like particle vaccine in prevention of infection with human papillomavirus types 16 and 18 in young women: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2004, 364 (9447): 1757-1765. 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17398-4.

ᅟ: HPV vaccine prevents CIN. J Fam Pract. 2006, 55 (4): 285-

The GlaxoSmithKline Vaccine HPV-007 Study Group: Sustained efficacy and immunogenicity of the human papillomavirus (HPV)-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted vaccine: analysis of a randomised placebo-controlled trial up to 64 years. The Lancet. 2009, 374 (9706): 1975-1985.

De CN, Teixeira J, Roteli-Martins CM, Naud P, De BP, Zahaf T, Sanchez N, Schuind A: Sustained efficacy and immunogenicity of the HPV-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted vaccine up to 7.3 years in young adult women. Vaccine. 2010, 28 (38): 6247-6255. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.07.007.

Roteli-Martins CM, Naud P, De Borba P, Teixeira JC, De Carvalho NS, Zahaf T, Sanchez N, Geeraerts B, Descamps D: Sustained immunogenicity and efficacy of the HPV-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted vaccine up to 8.4 years of follow-up. Hum Vaccine Immunotherapeutics. 2012, 8 (3): 390-397. 10.4161/hv.18865.

Villa LL, Costa RLR, Petta CA, Andrade RP, Ault KA, Giuliano AR, Wheeler CM, Koutsky LA, Malm C, Lehtinen M, Skjeldestad FE, Olsson SE, Steinwall M, Brown DR, Kurman RJ, Ronnett BM, Stoler MH, Ferenczy A, Harper DM, Tamms GM, Yu J, Lupinacci L, Railkar R, Taddeo FJ, Jansen KU, Esser MT, Sings HL, Saah AJ, Barr E: Prophylactic quadrivalent human papillomavirus (types 6, 11, 16, and 18) L1 virus-like particle vaccine in young women: a randomised double-blind placebo-controlled multicentre phase II efficacy trial. Lancet Oncol. 2005, 6 (5): 271-278. 10.1016/S1470-2045(05)70101-7.

Szarewski A, Poppe WAJ, Skinner SR, Wheeler CM, Paavonen J, Naud P, Salmeron J, Chow SN, Apter D, Kitchener H, Castellsagué X, Teixeira JC, Hedrick J, Jaisamrarn U, Limson G, Garland S, Romanowski B, Aoki FY, Schwarz TF, Bosch FX, Harper DM, Hardt K, Zahaf T, Descamps D, Struyf F, Lehtinen M, Dubin G, HPV PATRICIA Study Group: Efficacy of the human papillomavirus (HPV)-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted vaccine in women aged 15-25 years with and without serological evidence of previous exposure to HPV-16/18. Int J Cancer. 2012, 131 (1): 106-116. 10.1002/ijc.26362.

Kang S, Kim KH, Kim YT, Kim JH, Song YS, Shin SH, Ryu HS, Han JW, Kang JH, Park SY: Safety and immunogenicity of a vaccine targeting human papillomavirus types 6, 11, 16 and 18: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial in 176 Korean subjects. Int J Gynecol Cancer. 2008, 18 (5): 1013-1019. 10.1111/j.1525-1438.2007.01123.x.

Yoshikawa H, Ebihara K, Tanaka Y, Noda K: Efficacy of quadrivalent human papillomavirus (types 6, 11, 16 and 18) vaccine (GARDASIL) in Japanese women aged 18-26 years. Cancer Sci. 2013, 104 (4): 465-472. 10.1111/cas.12106.

Leroux-Roels G, Haelterman E, Maes C, Levy J, De BF, Licini L, David M-P, Dobbelaere K, Descamps D: Randomized trial of the immunogenicity and safety of the hepatitis B vaccine given in an accelerated schedule coadministered with the human papillomavirus type 16/18 AS04-adjuvanted cervical cancer vaccine. Clin Vaccine Immunol. 2011, 18 (9): 1510-1518. 10.1128/CVI.00539-10.

Einstein MH, Baron M, Levin MJ, Chatterjee A, Edwards RP, Zepp F, Carletti I, Dessy FJ, Trofa AF, Schuind A, Dubin G, HPV-010 Study Group: Comparison of the immunogenicity and safety of Cervarix and Gardasil human papillomavirus (HPV) cervical cancer vaccines in healthy women aged 18-45 years. Hum Vaccin. 2009, 5 (10): 705-719. 10.4161/hv.5.10.9518.

Ngan HY, Cheung AN, Tam KF, Chan KK, Tang HW, Bi D, Descamps D, Bock HL: Human papillomavirus-16/18 AS04-adjuvanted cervical cancer vaccine: immunogenicity and safety in healthy Chinese women from Hong Kong. Hong Kong Med J. 2010, 16 (3): 171-179.

Goldenthal KL, Pratt DR: Preventive Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Vaccines- regulatory briefing document on endpoints vaccines and related biological products advisory committee meeting November 28 and 29, 2001. 2001, http://www.fda.gov/ohrms/dockets/ac/01/briefing/3805b1_01.htm (accessed 2013 june 14)

Holowaty P, Miller AB, Rohan T, To T: Natural history of dysplasia of the uterine cervix. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1999, 91 (3): 252-258. 10.1093/jnci/91.3.252.

Clifford GM, Smith JS, Aguado T, Franceschi S: Comparison of HPV type distribution in high-grade cervical lesions and cervical cancer: a meta-analysis. Br J Cancer. 2003, 89 (1): 101-105. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601024.

Tabrizi SN, Brotherton JM, Kaldor JM, Skinner SR, Cummins E, Liu B, Bateson D, McNamee K, Garefalakis M, Garland SM: Fall in human papillomavirus prevalence following a national vaccination program. J Infect Dis. 2012, 206 (11): 1645-1651. 10.1093/infdis/jis590. doi: 1610.1093/infdis/jis1590. Epub 2012 Oct 1619

Kavanagh K, Pollock KG, Potts A, Love J, Cuschieri K, Cubie H, Robertson C, Donaghy M: Introduction and sustained high coverage of the HPV bivalent vaccine leads to a reduction in prevalence of HPV 16/18 and closely related HPV types. Br J Cancer. 2014, 110 (11): 2804-2811. 10.1038/bjc.2014.198. doi:2810.1038/bjc.2014.2198. Epub 2014 Apr 2815

Niccolai LM, Julian PJ, Meek JI, McBride V, Hadler JL, Sosa LE: Declining rates of high-grade cervical lesions in young women in Connecticut, 2008-2011. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2013, 22 (8): 1446-1450. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-13-0272. doi:1410.1158/1055-9965.EPI-1413-0272. Epub 2013 May 1423

Brotherton JM, Tabrizi SN, Garland SM: Does HPV type 16 or 18 prevalence in cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3 lesions vary by age? An important issue for postvaccination surveillance. Future Microbiol. 2012, 7 (2): 193-199. 10.2217/fmb.11.161. doi:110.2217/fmb.2211.2161

Rana MM, Al E: Understanding long-term protection of human papillomavirus vaccination against cervical carcinoma: Cancer registry-based follow-up. Int J Cancer. 2013, 132 (12): 2833-2838. 10.1002/ijc.27971.

Benard VB, Eheman CR, Lawson HW, Blackman DK, Anderson C, Helsel W, Thames SF, Lee NC: Cervical screening in the National Breast and Cervical Cancer Early Detection Program, 1995-2001. Obstet Gynecol. 2004, 103 (3): 564-571. 10.1097/01.AOG.0000115510.81613.f0.

Nygard JF, Skare GB, Thoresen SO: The cervical cancer screening programme in Norway, 1992-2000: changes in Pap smear coverage and incidence of cervical cancer. J Med Screen. 2002, 9 (2): 86-91. 10.1136/jms.9.2.86.

Bray F, Loos AH, McCarron P, Weiderpass E, Arbyn M, Moller H, Hakama M, Parkin DM: Trends in cervical squamous cell carcinoma incidence in 13 European countries: changing risk and the effects of screening. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2005, 14 (3): 677-686. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-04-0569.

Franco EL, Cuzick J, Hildesheim A, De Sanjose S: Chapter 20: issues in planning cervical cancer screening in the era of HPV vaccination. Vaccine. 2006, 24 (Suppl 3): S3/171-177. Epub 2006 Jun 2008

Lehtinen M, Paavonen J: Vaccination against human papillomaviruses shows great promise. Lancet. 2004, 364 (9447): 1731-1732. 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17410-2.

Tota JE, Ramanakumar AV, Jiang M, Dillner J, Walter SD, Kaufman JS, Coutlee F, Villa LL, Franco EL: Epidemiologic approaches to evaluating the potential for human papillomavirus type replacement postvaccination. Am J Epidemiol. 2013, 178 (4): 625-634. 10.1093/aje/kwt018. doi:610.1093/aje/kwt1018. Epub 2013 May 1099

Palmroth J, Merikukka M, Paavonen J, Apter D, Eriksson T, Natunen K, Dubin G, Lehtinen M: Occurrence of vaccine and non-vaccine human papillomavirus types in adolescent Finnish females 4 years post-vaccination. Int J Canc J Int Canc. 2012, 131 (12): 2832-2838. 10.1002/ijc.27586.

Kulasingam SL, Pagliusi S, Myers E: Potential effects of decreased cervical cancer screening participation after HPV vaccination: an example from the U.S. Vaccine. 2007, 25 (48): 8110-8113. 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.09.035. Epub 2007 Oct 8114

Panagopoulou E, Giata O, Montgomery A, Dinas K, Benos A: Human papillomavirus and cervical screening: misconceptions undermine adherence. Am J Health Promot. 2011, 26 (1): 6-9. 10.4278/ajhp.09113-ARB-364. doi:10.4278/ajhp.09113-ARB-09364

de Blasio BF, Neilson AR, Klemp M, Skjeldestad FE: Modeling the impact of screening policy and screening compliance on incidence and mortality of cervical cancer in the post-HPV vaccination era. J Public Health (Oxf). 2012, 34 (4): 539-547. 10.1093/pubmed/fds040.

Wright TC, Bosch FX, Franco EL, Cuzick J, Schiller JT, Garnett GP, Meheus A: Chapter 30: HPV vaccines and screening in the prevention of cervical cancer; conclusions from a 2006 workshop of international experts. Vaccine. 2006, 24 (Suppl 3): S3/251-261.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2458/14/867/prepub

Acknowledgement

We thank Ingrid Harboe for developing the search strategy and performing the literature search.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Elisabeth Couto, Ingvil Sæterdal contributed equally to this work.

Electronic supplementary material

Authors’ original submitted files for images

Below are the links to the authors’ original submitted files for images.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Couto, E., Sæterdal, I., Juvet, L.K. et al. HPV catch-up vaccination of young women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health 14, 867 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-14-867

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-14-867