Abstract

Background

One of the most effective ways to promote the prevention of mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) of HIV-1 in resource-limited settings is to encourage HIV-positive mothers to practice exclusive breastfeeding (EBF) for the first 6 months post-partum while they receive antiretroviral therapy (ARV). Although EBF reduces mortality in this context, its practice has been low. We studied the rate of adherence to EBF and assessed associated maternal and infant characteristics using data from a phase II PMTCT clinical trial conducted in Western Kenya which included a counseling intervention to encourage EBF by all participants.

Methods

We analyzed data from the Kisumu Breastfeeding Study (KiBS), conducted between July 2003 and February 2009. This study enrolled a total of 522 HIV-1 infected pregnant women. Data on breastfeeding were available for 480 mother-infant pairs. Infant feeding and general nutrition counseling began at 35 weeks gestation and continued throughout the 6 month post-partum intervention period, following World Health Organization (WHO) infant feeding guidelines. Data on infant feeding were collected during routine clinic visits and home visits using food frequency questionnaires and dietary recall methods. Participants were instructed to exclusively breastfeed until initiation of weaning at 5.5 months post-partum. We used Kaplan-Meier methods to estimate the rates of EBF at 5.25 months post-partum, stratified by maternal and infant characteristics measured at enrollment, delivery, and 2 weeks post-partum.

Results

The estimated EBF rate at 5.25 months post-partum was 80.4%. Only 3% of women introduced other foods (most commonly water with or without glucose, cow’s milk, formula, and fruit) by 2 months; this percentage increased to 5% of women by 4 months. Women who had ≥3 previous births (p < 0.01) and who were not living with the infant’s father (p = 0.04) were more likely to exclusively breastfeed. Mixed feeding was more common for male infants than for female infants (p = 0.04).

Conclusion

Exclusive breastfeeding was common in this clinical trial, which emphasized EBF as a best practice until infants reached 5.5 months of age. Counseling initiated prior to delivery and continued during the post-partum period provided a consistent message reinforcing the benefits of EBF. The findings from this study suggest high adherence to EBF in resource limited settings can be achieved by a comprehensive counseling intervention that encourages EBF.

Similar content being viewed by others

Explore related subjects

Find the latest articles, discoveries, and news in related topics.Background

For the prevention of mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) of HIV-1 in resource limited settings, the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends that HIV-infected mothers receive antiretroviral therapy (ARV) and practice exclusive breastfeeding (EBF) for the first 6 months post-partum followed by complementary feeding unless environmental and social circumstances are safe for and supportive of replacement feeding [1]. In addition to the significant gains in reducing HIV transmission through PMTCT prophylaxis during pregnancy, studies have shown an association between EBF and decreased HIV transmission in the first 6 months of infant life compared to mixed feeding [2–8]. Despite WHO recommendations promoting EBF practices, adherence to EBF is often low [7, 9–12]. EBF remains a challenge in sub-Saharan Africa, as it culturally more acceptable to provide mixed feeding with supplemental fluids or other foods traditional for infants [11, 12]. Globally, less than 40% of infants under 6 months of age are exclusively breastfed [13]. In sub-Saharan Africa, pre-lacteal feeding [10, 14], mixed feeding as early as 2 weeks after delivery, and breastfeeding beyond 2 years are common [15]. Multiple studies have highlighted various predictors of breastfeeding practices, such as societal norms [16], cultural beliefs [14, 17, 18], age [19–23], socioeconomic status [11, 14, 24], medical problems [16, 21, 25], psychosocial factors [26], and family influence [12, 17, 27–32]. While some studies have focused on the challenges of EBF, there is limited data from clinical trials in this region on the successes of EBF.

The focus of this analysis was to estimate the proportion of mothers who adhered to the current recommendations to exclusively breastfeed for 5.25 months in the context of a PMTCT clinical trial with access to appropriate ARV therapy. Factors previously known to be associated with EBF, such as age [19–23] and socioeconomic status [11, 14, 24], among others, were examined to determine whether they increased or decreased adherence to EBF during the first 6 months post-partum.

Methods

This analysis uses data obtained from participants enrolled in the Kisumu Breastfeeding Study (KiBS), an open label phase IIb PMTCT clinical trial conducted between July 2003 and February 2009 (ClinicalTrials.gov NCT00146380). A detailed description of the study design and methods has previously been published [33]. In brief, HIV-infected pregnant women attending PMTCT programs at the antenatal clinics of the New Nyanza Provincial General Hospital and the Kisumu District Hospital, which serve lower income populations of Kisumu, were counseled on the risks and benefits of various infant feeding options. After receiving infant feeding counseling, women who indicated intent to breastfeed and met other study inclusion criteria were enrolled at 34 weeks gestation. All study participants were ARV naïve and received triple-combination ARV therapy consisting of zidovudine/lamivudine coformulated as combivir (GlaxoSmithKline) with either nevirapine (Viramune, Boehringer Ingelheim) or nelfinavir (Viracept, Hoffman-La Roche Ltd.). Participants received ARV therapy from 34 weeks gestation through 6 months post-partum. Plasma viral load was quantified using the Amplicor HIV-1 RNA Monitor Test v1.5 (Roche Diagnostics). CD4 lymphocytes were analyzed on a FACSCalibur flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson).

In accordance with WHO guidelines, women were counseled to exclusively breastfeed their infants for 5.5 months and then to wean them promptly over a 2-week period, with complete cessation of breastfeeding by 6 months post-partum. ARVs were discontinued at 6 months post-partum unless the participants met WHO guidelines for their own treatment at the time of the study. EBF was defined as feeding with only breast milk. Medicines and herbs for medicinal purposes were allowed. Mixed feeding was defined as the ingestion of any liquid or food in addition to breast milk. The use of locally available liquids and foods (e.g., porridge, soups, fruit juices, and cow’s milk) was encouraged for weaning and replacement feeding.

The study protocol was approved by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Institutional Review Board in Atlanta and the Kenya Medical Research Institute (KEMRI) Ethics Review Committee. All participants provided written consent before enrolling in the study.

Data collection and analysis

Infant feeding and general nutrition counseling began after enrollment at 34 weeks gestation. Participants were seen weekly at the clinic for clinical evaluation and received counseling on: maternal nutrition, preparation for lactation, importance of EBF, good breastfeeding techniques, breast health, common breastfeeding problems and strategies for reducing breast milk transmission of HIV in a breastfeeding infant. Home visits also occurred weekly after enrollment at 34 weeks gestation by social workers with certificates in counseling and social work to assess maternal progress since starting the study drugs and to reinforce the benefits of EBF, in preparation for lactation. The time spent for home visits averaged 40 to 60 minutes. After delivery, each mother-infant pair was seen in the clinic for follow-up at 2, 6, 10, and 14 weeks post-partum by a clinician and a nutritionist. During clinic visits participants received counseling to reinforce EBF and an assessment of breast health. Data was collected at each of the visits. At 5 months the mother-infant pair was seen at the clinic by the nutritionist, who discussed with them making the transition from EBF to replacement feeding at 5.5 months post-partum. Mothers and infants continued to be followed at 6, 9, 12, 15, 18, and 24 months post-partum. Three clinic visits were later added at 5, 7, and 8 months post-partum to monitor infant growth around the weaning period. During study visits adherence to medications and infant feeding recommendations were assessed by study coordinators. Infant feeding counseling was carried out using WHO 2006 guidelines for HIV and infant feeding. In addition, home visits were conducted with monitoring of infant feeding between the clinic visits at 1, 4, 8, 12, and 16 weeks and at 6, 7, 8, 10, 11, 14, 17, 20, and 22 months post-partum. During home visits the interviewer directly observed the home environment and interviewed other household members caring for the infant to assess whether the infant was being fed other foods or still breastfeeding. During each interview conducted at clinic and home visits, data was collected through face-to-face interviews with participants and via observation on infant feeding practices, including: breastfeeding, breast health problems, introduction of complementary liquids or foods, and cessation of breastfeeding. Data from both interviews and direct observations were recorded on case report forms and were considered equally in determining when mixed feeding first occurred. Any report of liquids or foods other than breast milk was considered to be evidence of mixed feeding.

The time of the first mixed feed was calculated based on data from multiple sources: the current breastfeeding question in the clinic visit form, the current breastfeeding question and evidence of current mixed feeding (e.g., baby seen eating other foods, food on baby’s clothes) in the home visit form, the breastfeeding cessation date form, and a mixed feeding form. This last form for mixed feeding lists the liquids and foods other than breast milk, (i.e., water, glucose water, tea, juice, formula, fresh milk, porridge, and fruits) given to the infant over 3 days prior to the current visit, if the participant reported either having difficulty maintaining EBF or having practiced mixed feeding. Case report forms for recording data were processed by an automated teleform system.

Statistical analyses were performed on data obtained on 480 mothers and their live-born infants for whom any breastfeeding data were available. The cumulative counts and percentages of various liquids and foods were computed by time after delivery for visits scheduled at 2, 6, 10, and 14 weeks and 5 and 6 months post-partum (corresponding to 14, 42, 70, 98, 152, and 183 days post-partum, respectively). Measurements that occurred within 2 weeks (14 days) after each scheduled visit were included with that scheduled visit. Summary statistics were computed for various maternal and infant socio-demographic and clinical characteristics. Kaplan-Meier methods were used to calculate the rates of EBF at 5.25 months (160 days) post-partum, stratified by maternal and infant characteristics measured at enrollment, delivery, and 2 weeks post-partum. The event of interest was time of first mixed feeding, and observations were censored for loss to follow-up and withdrawal from the study. In addition, 95% confidence intervals were computed on the complementary log-log scale using the Greenwood variance estimator. Cochran’s Q test was used to test for heterogeneity among the strata in the estimated EBF rates at 5.25 months post-partum. A 5% significance level was chosen. All computations were performed using SAS software, version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

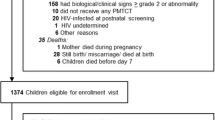

The study enrolled 522 HIV-1 infected pregnant women, of whom 491 delivered 502 live infants. Data on breastfeeding were available for 480 mother-infant pairs.

Maternal baseline socio-demographic and clinical characteristics are listed in Table 1. The largest proportion of women (43%) were between 20–24 years of age, 74% were married, 72% had completed primary education, 35% were employed outside of the home, and 84% were at WHO clinical disease stage 1.

The majority of women in the study adhered to the suggested guidelines to exclusively breastfeed up to 5.5 months post-partum, as indicated by the Kaplan-Meier analysis in Table 1. At 5.25 months post-partum, 80.4% of those in the study were still exclusively breastfeeding. Two of the maternal characteristics measured at enrollment (Table 1) were associated with EBF. Among multigravid women, those who had ≥3 children were more likely to exclusively breastfeed than those who had 0–2 children (89.8% vs. 77.4%, p < 0.01). Also, women who were not living with the child’s father were more likely to exclusively breastfeed than women who were living with the child’s father (86.0% vs. 78.1%, p = 0.04). When we examined maternal and infant characteristics measured at delivery and 2 weeks post-partum (Table 2), female infants were more likely to be exclusively breastfed compared to male infants (84.5% vs. 76.9%, p = 0.04). None of the other variables were significantly associated with EBF at the 5% significance level. When mixed feeding was practiced prior to the suggested weaning period, the most commonly given liquids and foods were milk, water with or without glucose, fruit, and porridge (Table 3). Only 3% and 5% of women introduced fluids other than breast milk by 2 and 4 months post-partum, respectively. Only 4 women gave their infants formula prior to 6 months post-partum, and the percentage remained small even during the period of suggested weaning.

Discussion

Our findings of 80.4% overall adherence to EBF at 5.25 months post-partum in this study is much higher than expected, given global estimates of 39% and Kenya national estimates of 32% [34]. A likely explanation for the higher EBF adherence in this study was the comprehensive support provided to participants in this PMTCT clinical trial. After enrollment, participants were engaged with clinic personnel who provided frequent reinforcement to adhere to EBF for 5.5 months until weaning. Likewise, a KiBS sub-study that focused on a safe water intervention also reported high adherence (80% to 90%) to the recommended chlorine practices and a low frequency of clinic visits for diarrheal cases during the EBF period [35]. In contrast to our findings of high adherence to recommendations for EBF until 5.5 months post-partum, a recent study to examine feeding practices among HIV-infected and uninfected mothers in Kisumu, Kenya, where this clinical trial was conducted, found only 14% of HIV-infected women practiced EBF for the first 6 months post-partum [24]. We assert that high adherence to EBF may be a positive result of providing counseling and routine follow-up in this clinical trial setting. Providing regular and consistent messaging to mothers, as was done in this PMTCT clinical trial, can facilitate compliance with WHO breastfeeding recommendations and best practices in resource limited settings.

In this study we found that the EBF rate was higher among multigravid women who had ≥3 children prior to enrollment than among those with 0–2 children. One possible explanation for this finding is that women may find it easier to exclusively breastfeed having had previous experience with breastfeeding. Also, EBF is less expensive than mixed feeding, and cost may be a concern in larger families. Likewise, the EBF rate was higher among women not living with the child’s father than among women living with the child’s father. Women not living with the child’s father may find more time to spend alone with their infant, making EBF more convenient. In addition, the mixed feeding rate was higher among male infants than among female infants. This observation may reflect the cultural context that places higher regard on male infants in this region of Kenya and therefore seeks to give them the best nutrition and care. Thus, there may be a greater likelihood to start mixed feeding male infants earlier because supplementing breast milk with nutritious foods is thought to promote growth and development [14].

There are several limitations to our analysis. The high rate of EBF might be related to recruitment into the clinical trial of women who planned to breastfeed. However, the high rate of EBF reflects not only the fact that that these women breastfed their infants, but also the fact that they refrained from mixed feeding, in contrast to the most common practice in Kenya, as in the rest of sub-Saharan Africa. Furthermore, there were frequent clinic and home visits with continuous counseling and support for EBF, which likely impacted infant feeding practices. Social desirability bias may have been introduced through individuals answering questions that they exclusively breastfed since this is what was expected of them and considered most appropriate rather than what was actually done. Nevertheless, attempts were made to observe infant behavior and feeding practices in the home by social workers during home visits. Feeding habits were also discussed with family members during home visits.

Clinical trials and other interventions that provide education and reinforcement, such as peer counselors, can have a positive impact on improving the knowledge and attitudes about EBF [30]. Progress to increase the number of women who exclusively breastfeed has been reported on a large scale in Africa and Latin America through training, effective behavior change communication and the development of key partnerships which influenced communities [15, 36]. It may be challenging to translate the experience from this clinical trial to busy clinic settings in resource constrained areas with limited staff. Use of community volunteers to emphasize the importance of EBF could prove valuable in these settings. Use of peer counselors in the PROMISE EBF study demonstrated a significant increase in EBF prevalence for women who were randomized to a peer counseling intervention which involved one antenatal and four post-delivery breastfeeding peer counseling sessions, compared to a control group. The EBF prevalence at 12 weeks post-delivery in the intervention and control clusters was 79% vs. 35% in Burkina Faso, 82% vs. 44% in Uganda, and 10% vs. 6% in South Africa [37]. The interpretation from this study was that low intensity individual peer counseling can be used to effectively increase EBF prevalence in sub-Saharan African settings. These results and ours suggest that education and counseling from health care providers and community workers in resource-limited settings can improve adherence to the current breastfeeding guidelines.

Conclusion

Health care and community workers can have a pivotal role in providing accurate information on the benefits of EBF, leading to optimal feeding practices and decreased infant morbidity and mortality. In resource-limited settings, strategies to promote EBF and to discourage early mixed feeding should be incorporated routinely within maternal child health programs.

References

World Health Organization (WHO): Guidelines on HIV and Infant Feeding 2010: Principles and Recommendations for Infant Feeding in the Context of HIV and a Summary of Evidence. 2010, Geneva: WHO

Iliff PJ, Piwoz EG, Tavengwa NV, Zunguza CD, Marinda ET, Nathoo KJ, Moulton LH, Ward BJ, Humphrey JH, the ZVITAMBO study group: Early exclusive breastfeeding reduces the risk of postnatal HIV-1 transmission and increases HIV-free survival. AIDS. 2005, 19 (7): 699-708. 10.1097/01.aids.0000166093.16446.c9.

Magoni M, Bassani L, Okong P, Kituuka P, Germinario EP, Giuliano M, Vella S: Mode of infant feeding and HIV infection in children in a program for prevention of mother-to-child transmission in Uganda. AIDS. 2005, 19 (4): 433-437. 10.1097/01.aids.0000161773.29029.c0.

Coovadia HM, Rollins NC, Bland RM, Little K, Coutsoudis A, Bennish ML, Newell ML: Mother-to-child transmission of HIV-1 infection during exclusive breastfeeding in the first 6 months of life: an intervention cohort study. Lancet. 2007, 369 (9567): 1107-1116. 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60283-9.

Becquet R, Ekouevi DK, Menan H, Amani-Bosse C, Bequet L, Viho I, Dabis F, Timite-Konan M, Leroy V, ANRS 1201/1202 Ditrame Plus Study Group: Early mixed feeding and breastfeeding beyond 6 months increase the risk of postnatal HIV transmission: ANRS 1201/1202 Ditrame Plus, Abidjan, Côte d'Ivoire. Prev Med. 2008, 47 (1): 27-33. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2007.11.014.

Becquet R, Bland R, Leroy V, Rollins NC, Ekouevi DK, Coutsoudis A, Dabis F, Coovadia HM, Salamon R, Newell ML: Duration, pattern of breastfeeding and postnatal transmission of HIV: pooled analysis of individual data from West and South African cohorts. PLoS One. 2009, 4 (10): e7397-10.1371/journal.pone.0007397.

Lunney KM, Iliff P, Mutasa K, Ntozini R, Magder LS, Moulton LH, Humphrey JH: Associations between breast milk viral load, mastitis, exclusive breast-feeding, and postnatal transmission of HIV. Clin Infect Dis. 2010, 50 (5): 762-769.

John-Stewart G, Mbori-Ngacha D, Ekpini R, Janoff EN, Nkengasong J, Read JS, Van de Perre P, Newell ML, for the Ghent IAS Working Group on HIV in Women and Children: Breast-feeding and Transmission of HIV-1. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2004, 35 (2): 196-202. 10.1097/00126334-200402010-00015.

Lauer JA, Betran AP, Victora CG, de Onis M, Barros AJ: Breastfeeding patterns and exposure to suboptimal breastfeeding among children in developing countries: review and analysis of nationally representative surveys. BMC Med. 2004, 2: 26-10.1186/1741-7015-2-26.

Engebretsen IM, Wamani H, Karamagi C, Semiyaga N, Tumwine J, Tylleskar T: Low adherence to exclusive breastfeeding in Eastern Uganda: a community-based cross-sectional study comparing dietary recall since birth with 24-hour recall. BMC Pediatr. 2007, 7: 10-10.1186/1471-2431-7-10.

Fadnes LT, Engebretsen IM, Wamani H, Semiyaga NB, Tylleskar T, Tumwine JK: Infant feeding among HIV-positive mothers and the general population mothers: comparison of two cross-sectional surveys in Eastern Uganda. BMC Public Health. 2009, 9: 124-10.1186/1471-2458-9-124.

Cames C, Saher A, Ayassou KA, Cournil A, Meda N, Simondon KB: Acceptability and feasibility of infant-feeding options: experiences of HIV-infected mothers in the World Health Organization Kesho Bora mother-to-child transmission prevention (PMTCT) trial in Burkina Faso. Matern Child Nutr. 2010, 6 (3): 253-265.

United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF): The State of the World’s Children 2009: Maternal and Newborn Health. 2008, New York: UNICEF

Engebretsen IM, Moland KM, Nankunda J, Karamagi CA, Tylleskar T, Tumwine JK: Gendered perceptions on infant feeding in Eastern Uganda: continued need for exclusive breastfeeding support. Int Breastfeed J. 2010, 5: 13-10.1186/1746-4358-5-13.

Abiona TC, Onayade AA, Ijadunola KT, Obiajunwa PO, Aina OI, Thairu LN: Acceptability, feasibility and affordability of infant feeding options for HIV-infected women: a qualitative study in south-west Nigeria. Matern Child Nutr. 2006, 2 (3): 135-144. 10.1111/j.1740-8709.2006.00050.x.

Maman S, Cathcart R, Burkhardt G, Omba S, Thompson D, Behets F: The infant feeding choices and experiences of women living with HIV in Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of Congo. AIDS Care. 2012, 24 (2): 259-265.

Thairu LN, Pelto GH, Rollins NC, Bland RM, Ntshangase N: Sociocultural influences on infant feeding decisions among HIV-infected women in rural Kwa-Zulu Natal, South Africa. Matern Child Nutr. 2005, 1 (1): 2-10. 10.1111/j.1740-8709.2004.00001.x.

Osman H, El Zein L, Wick L: Cultural beliefs that may discourage breastfeeding among Lebanese women: a qualitative analysis. Int Breastfeed J. 2009, 4: 12-10.1186/1746-4358-4-12.

Kiarie JN, Richardson BA, Mbori-Ngacha D, Nduati RW, John-Stewart GC: Infant feeding practices of women in a perinatal HIV-1 prevention study in Nairobi, Kenya. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2004, 35 (1): 75-81. 10.1097/00126334-200401010-00011.

Ssenyonga R, Muwonge R, Nankya I: Towards a better understanding of exclusive breastfeeding in the era of HIV/AIDS: a study of prevalence and factors associated with exclusive breastfeeding from birth, in Rakai, Uganda. J Trop Pediatr. 2004, 50 (6): 348-353. 10.1093/tropej/50.6.348.

Naanyu V: Young mothers, first time parenthood and exclusive breastfeeding in Kenya. Afr J Reprod Health. 2008, 12 (3): 125-137.

Scott JA, Binns CW, Graham KI, Oddy WH: Predictors of the early introduction of solid foods in infants: results of a cohort study. BMC Pediatr. 2009, 9: 60-10.1186/1471-2431-9-60.

Ladzani R, Peltzer K, Mlambo MG, Phaweni K: Infant-feeding practices and associated factors of HIV-positive mothers at Gert Sibande, South Africa. Acta Paediatr. 2011, 100 (4): 538-542. 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2010.02080.x.

Gewa CA, Oguttu M, Savaglio L: Determinants of early child-feeding practices among HIV-infected and noninfected mothers in rural Kenya. J Hum Lact. 2011, 27 (3): 239-249. 10.1177/0890334411403930.

Nankunda J, Tumwine JK, Soltvedt A, Semiyaga N, Ndeezi G, Tylleskar T: Community based peer counsellors for support of exclusive breastfeeding: experiences from rural Uganda. Int Breastfeed J. 2006, 1: 19-10.1186/1746-4358-1-19.

Webb-Girard A, Cherobon A, Mbugua S, Kamau-Mbuthia E, Amin A, Sellen DW: Food insecurity is associated with attitudes towards exclusive breastfeeding among women in urban Kenya. Matern Child Nutr. 2012, 8 (2): 199-214. 10.1111/j.1740-8709.2010.00272.x.

Bland RM, Rollins NC, Coutsoudis A, Coovadia HM, Child Health G: Breastfeeding practices in an area of high HIV prevalence in rural South Africa. Acta Paediatr. 2002, 91 (6): 704-711. 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2002.tb03306.x.

Becquet R, Ekouevi DK, Viho I, Sakarovitch C, Toure H, Castetbon K, Coulibaly N, Timite-Konan M, Bequet L, Dabis F, Leroy V: Acceptability of exclusive breast-feeding with early cessation to prevent HIV transmission through breast milk, ANRS 1201/1202 Ditrame Plus, Abidjan, Côte d'Ivoire. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2005, 40 (5): 600-608. 10.1097/01.qai.0000171726.17436.82.

Tijou Traore A, Querre M, Brou H, Leroy V, Desclaux A, Desgrees-du-Lou A: Couples, PMTCT programs and infant feeding decision-making in Ivory Coast. Soc Sci Med. 2009, 69 (6): 830-837. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.06.001.

Nankunda J, Tylleskar T, Ndeezi G, Semiyaga N, Tumwine JK, for the PROMISE-EBF Study Group: Establishing individual peer counselling for exclusive breastfeeding in Uganda: implications for scaling-up. Matern Child Nutr. 2010, 6 (1): 53-66. 10.1111/j.1740-8709.2009.00187.x.

Maru S, Datong P, Selleng D, Mang E, Inyang B, Ajene A, Guyit R, Charurat M, Abimiku A: Social determinants of mixed feeding behavior among HIV-infected mothers in Jos, Nigeria. AIDS Care. 2009, 21 (9): 1114-1123. 10.1080/09540120802705842.

Falnes EF, Moland KM, Tylleskar T, de Paoli MM, Leshabari SC, Engebretsen IM: The potential role of mother-in-law in prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV: a mixed methods study from the Kilimanjaro region, northern Tanzania. BMC Public Health. 2011, 11: 551-10.1186/1471-2458-11-551.

Thomas TK, Masaba R, Borkowf CB, Ndivo R, Zeh C, Misore A, Otieno J, Jamieson D, Thigpen MC, Bulterys M, Slutsker L, De Cock KM, Amornkul PN, Greenberg AE, Fowler MG, for the KiBS Study Team: Triple-antiretroviral prophylaxis to prevent mother-to-child HIV transmission through breastfeeding–the Kisumu breastfeeding study, Kenya: a clinical trial. PLoS Med. 2011, 8 (3): e1001015-10.1371/journal.pmed.1001015.

Kenya National Bureau of Statistics (KNBS) and ICF Macro: Kenya Demographic and Health Survey 2008–09. 2010, Calverton, Maryland: KNBS and ICF Macro

Harris JR, Greene SK, Thomas TK, Ndivo R, Okanda J, Masaba R, Nyangau I, Thigpen MC, Hoekstra RM, Quick RE: Effect of a point-of-use water treatment and safe water storage intervention on diarrhea in infants of HIV-infected mothers. J Infect Dis. 2009, 200 (8): 1186-1193. 10.1086/605841.

Quinn VJ, Guyon AB, Schubert JW, Stone-Jimenez M, Hainsworth MD, Martin LH: Improving breastfeeding practices on a broad scale at the community level: success stories from Africa and Latin America. J Hum Lact. 2005, 21 (3): 345-354. 10.1177/0890334405278383.

Tylleskär T, Jackson D, Meda N, Engebretsen IM, Chopra M, Diallo AH, Doherty T, Ekström EC, Fadnes LT, Goga A, Kankasa C, Klungsøyr JI, Lombard C, Nankabirwa V, Nankunda JK, Van de Perre P, Sanders D, Shanmugam R, Sommerfelt H, Wamani H, Tumwine JK, PROMISE-EBF Study Group: Exclusive breastfeeding promotion by peer counsellors in sub-Saharan Africa (PROMISE-EBF): a cluster-randomised trial. Lancet. 2011, 378 (9789): 420-427. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60738-1.

Pre-publication history

The pre-publication history for this paper can be accessed here:http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2431/14/280/prepub

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to the study participants, the Kisumu Breastfeeding Study (KiBS) team, Kenya Medical Research Institute (KEMRI) and Kenya Ministry of Health whose participation made this study possible. We also thank Glaxo Smith Kline and Boehringer Ingelheim for providing the study medications, the Division of HIV/AIDS Prevention, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, Georgia, USA for funding. KEMRI staff participated in the design, data collection, analysis and the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. This paper is published with the approval of the Director, Kenya Medical Research Institute.

Disclaimer

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors, and do not necessarily represent the views of their institutions, including the U.S. Centers for Diseases Control and Prevention and Kenya Medical Research Institute.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors’ contributions

JO contributed to the implementation of the study, analysis and writing of this manuscript. CBB conducted the statistical analyses, created tables, and contributed to the writing. SG provided data management and data analysis. TT contributed to the study design, initiated the study, and provided comments on the manuscript. SL supervised the development of the manuscript and contributed to the analysis and writing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Okanda, J.O., Borkowf, C.B., Girde, S. et al. Exclusive breastfeeding among women taking HAART for PMTCT of HIV-1 in the Kisumu Breastfeeding Study. BMC Pediatr 14, 280 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2431-14-280

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2431-14-280